APPENDIX A

What Is Empathy?

You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.

—INIGO MONTOYA, THE PRINCESS BRIDE

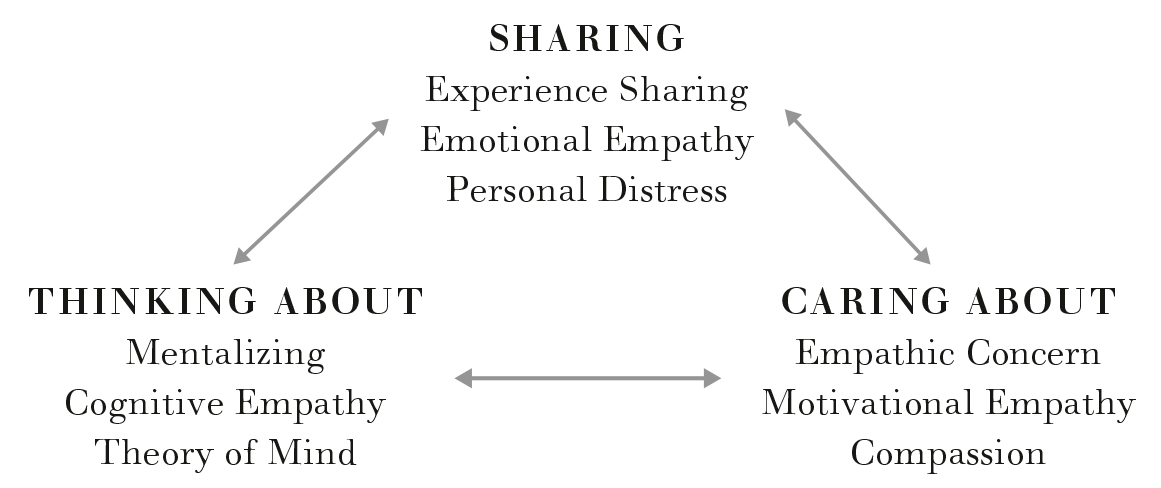

MOST OF US think we know what “empathy” is, yet we often mean different things when we use it. Psychologists have (sometimes heatedly) debated its definitions for decades. But despite our quibbling over details, most empathy researchers agree on the big picture. In particular, empathy is not really one thing at all. It’s an umbrella term that describes multiple ways people respond to one another, including sharing, thinking about, and caring about others’ feelings. These pieces, in turn, go by several names:

Let’s tackle these one at a time. To do so, imagine you’re a senior in college, walking with a close friend to his apartment. On your way in he checks his mailbox, then freezes. “Holy shit,” he says. “This is it.” You know what he means. You’ve seen him work relentlessly for three years in hopes of getting into medical school, and into one program in particular. He’s talked with you maybe thirty times since applying, alternately anxious, hopeful, or both. You rush upstairs, and he opens the envelope. His face contorts, and you lean forward, for a moment not knowing whether he’s ecstatic or upset. It becomes apparent that he is not crying happy tears.

SHARING

As your friend collapses into a heap, you might frown, slump, and even tear up yourself. Your mood will probably plummet. This is what empathy researchers call experience sharing: vicariously taking on the emotions we observe in others. Experience sharing is widespread—people “catch” one another’s facial expressions, bodily stress, and moods, both negative and positive. Our brains respond to each other’s pain and pleasure as though we were experiencing those states ourselves.

Experience sharing is the closest we come to dissolving the boundary between self and other. It is empathy’s leading edge. It is evolutionarily ancient, occurring in monkeys, mice, and even geese. It comes online early in life: Infants mimic each other’s cries and take on their mothers’ distress. And it occurs at lightning speed. Seeing your friend grimace, you might mimic his face in a fraction of a second, and parts of your brain associated with feeling pain might come online just as quickly.

Experience sharing also forms the foundation of empathy science. Even before the word “empathy” existed, philosophers such as Adam Smith described “sympathy,” or “fellow feeling” in ways that tightly match experience sharing. Smith, for instance, writes that “by changing places in fancy with the sufferer…we come to either conceive or to be affected by what he feels.” From “emotion contagion” in psychology to brain mirroring in neuroscience, experience sharing has long been the most famous piece of empathy.

THINKING

As you share your friend’s pain, you also create a picture of his inner life. How upset is he? What is he thinking about? What will he do now? To answer these questions, you think like a detective, gathering evidence about his behavior and situation to deduce how he feels. This cognitive piece of empathy is referred to as “mentalizing,” or explicitly considering someone else’s perspective. Mentalizing, an everyday form of mind reading, is more sophisticated than experience sharing. It requires cognitive firepower that most animals don’t have, and thus arrived later in evolution. And though children pick up experience sharing early, it takes them longer to sharpen their mentalizing skills.

CARING

If while your friend weeps, all you do is sit back, feel bad, and think about him, you’re a less-than-stellar pal. Instead, you might also wish for him to feel better and hatch a plan for how you can get him there. This is what researchers call “empathic concern,” or a motivation to improve someone else’s well-being. This is the piece of empathy that most reliably sparks kind action. Concern has received less attention from Western researchers than mentalizing or experience sharing, though that is now changing. Concern also hews tightly to centuries-old formulations of “compassion” in the Buddhist tradition, for instance karuna, or the desire to free others from suffering.

SPLITS AND CONNECTIONS

Experience sharing, mentalizing, and concern split apart in all sorts of interesting ways. For instance, mentalizing is most useful when we don’t share another’s experiences. To know why a fan of a team you don’t follow just climbed a signpost, you must understand differences between their emotional landscape and yours. When we fail to understand each other, it’s often because we falsely assume our own knowledge or priorities will map onto someone else’s.

Empathic processes activate different brain systems and are useful at different moments. Poker and boxing require keen mentalizing—What does your opponent know? What is her next move?—but are ill-served by concern. Parenting can be the opposite: You might never understand why your toddler is mid-meltdown, but you must still do what you can to help her. People also differ in their empathic landscapes. An emergency room physician likely feels great concern for her patients, but she cannot do her job if also taking on their pain. Individuals with autism spectrum disorder sometimes struggle at mentalizing, but they still share and care about others’ feelings. Psychopaths have the opposite profile: They are perfectly able to tell what others feel but are unaffected by their pain.

Despite these distinctions, empathic pieces are also deeply intertwined. Sharing someone else’s emotion draws our attention to what they feel, and thinking about them reliably increases our concern for their well-being. All three empathic processes promote kindness, albeit in distinct ways. The primatologist Frans de Waal describes this beautifully in his “Russian Doll Model” of empathy. As he sees it, the primitive process of experience sharing is at the core—turning someone else’s pain into our own creates an impulse to stop it. Newer, more complex forms of empathy are layered on top of that, generating broader sorts of kindness. Through mentalizing, we develop a fine-grained picture of not just what someone else feels, but why they feel it, and—more important—what might make them feel better. This spurs a deeper concern, a response focused not only on our own discomfort but truly on someone else. The global kindness Peter Singer describes in The Expanding Circle is a further extension of concern—pointed not at any one individual, but at people as a whole.

WORKING AT EMPATHY, ONE PIECE AT A TIME

This book focuses on rebuilding empathy when it’s eroded. Pinpointing different pieces of empathy helps researchers diagnose what has gone wrong and find the most effective solutions. Callousness can come from thoughtlessness: We discount the suffering of a homeless person because we don’t consider their experiences at all. In that case, interventions might focus on encouraging mentalizing, for instance, through perspective-taking exercises or virtual reality. In the face of conflict, we might think a great deal about our enemies but not care about their well-being (we may even hope for them to suffer). Contact, and especially friendships across group lines, can change that. Burnout—for instance, among medical professionals—often follows from too much experience sharing. Contemplative techniques can help people shift themselves toward concern instead. In all these cases, understanding what to do with empathy requires first understanding exactly what it is.