CHAPTER 1

The Surprising Mobility of Human Nature

Eppur si muove (And yet it moves).

—ATTRIBUTED TO GALILEO GALILEI

A CENTURY AGO, almost everyone believed the ground lay still beneath us. Australia had always been an island, Brazil and Senegal had always been separated by the Atlantic; it was too obvious to discuss. Alfred Wegener changed that. Wegener was that not-so-classic combination of adventurer and meteorologist. He broke a world record by floating above Europe in a weather-tracking balloon for more than two days. He trekked across Greenland, detonating bombs in the tundra to gauge how deep the ice caps were. He would die on one of those trips at the age of fifty.

Studying maps of the ocean floor, Wegener noticed that the continents complemented one another like puzzle pieces. “Doesn’t the east coast of South America fit exactly against the west coast of Africa, as if they had once been joined?” he wrote to a lady friend. “This is an idea I’ll have to pursue.” Wegener spotted other mysteries. The African plains were covered in scars left by ancient glaciers. If they had always been near the equator, how was that possible? Identical species of ferns and lizards were spread across Chile, India, and even Antarctica. How could they have traveled so far?

At that time, geologists believed that ancient land bridges once spanned the oceans, allowing life to crisscross between continents. This did not satisfy Wegener. In his 1915 book, The Origin of Continents and Oceans, he proposed a radical alternative. The earth’s land had once clumped together in a single mass—Wegener dubbed it “Pangea”—and for eons had rumbled apart into the continents we now know. The Atlantic Ocean was younger than people realized, and was growing. Animals that had evolved as neighbors had drifted to far-flung corners of the planet. The earth’s surface was moving—imperceptibly, but constantly.

Wegener’s idea did not land gently. Geologists ruthlessly mocked “continental drift,” as it came to be called. Wegener was not part of their field, and insiders couldn’t believe he had the gall to challenge their well-established notions, especially with such a strange idea. Summing up dozens of similar reactions, one researcher described continental drift as the “delirious ravings of people with bad cases of moving crust disease and wandering pole plague.” A few came to Wegener’s side, forming a small camp of geological “mobilists,” but traditional “fixists” succeeded in defending a stationary earth. As Rollin Chamberlin, editor of the Journal of Geology, wrote, “If we are to believe Wegener’s hypothesis we must forget everything which has been learned in the last 70 years and start all over again.” At the time of his death, Wegener’s theory had been tossed in the rubbish bin of scientific history.

Decades later, scientists discovered tectonic plates, masses larger than continents pushed along by currents of magma. The North American and Eurasian plates drift apart from each other about as fast as your fingernails grow; they’ve moved some three feet in my lifetime. Wegener, a scientific outsider with an unbelievable idea, had been right after all. Geology was rewritten to acknowledge that even things that appear still can move.

WE NOW ACCEPT that the earth and sky are forever changing, but our understanding of ourselves has proven more stubborn. Sure, we get old, our bones stiffen, and our hair turns gray, but our essence stays the same. Over the centuries, the supposed location of that essence has shifted. Theologians placed it in the eternal human soul; earthlier philosophers focused on natural character and virtue. In the modern era, human essence has become thoroughly biological, grounded in our genes and coded into our bodies.

No matter where human nature resides, it is assumed to be constant and immutable. I call this belief “psychological fixism,” because it views people the way geologists once saw the continents. Fixism can be comforting. It means we can know who others truly are, and know ourselves as well. But it also limits us. Cheaters will always cheat, and liars will always lie.

Phrenology, a nineteenth-century “science,” held that each mental faculty was housed in its own section of neural real estate. Phrenologists used calipers to measure the bumps and valleys on a person’s skull, determining their degree of benevolence or conscientiousness. This sort of fixism was useful in defending prevailing social hierarchies. The phrenologist Charles Caldwell toured the American South arguing that people of African descent had brains built for subjugation. Others used supposed biological truths to argue that women were not worth educating, the poor were destitute for good reason, and criminals could never be reformed. As a science, phrenology was bankrupt, but as an ideology, it was convenient.

By the early twentieth century, neuroscience had outgrown phrenology, but there remained a lingering sense that our biology was fixed. Researchers knew that the human brain developed in leaps and bounds throughout childhood—not just growing, but reshaping into a dazzling, intricate architecture. Then, for the most part, it appeared to stop. Using the tools available to them, neuroscientists couldn’t detect any changes after people reached adulthood. This jibed with popular notions about human nature, and became dogma. Scientists came to believe that cuts heal, but neurons lost to concussions, aging, or bachelorette parties were never replaced.

The father of modern neuroscience, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, described this idea: “In adult centers the nerve paths are something fixed, ended, immutable. Everything may die, nothing may be regenerated. It is for science of the future to change, if possible, this harsh decree.”

But science did not need to change this decree, only to realize it was wrong. One of the first discoveries to lead the way came about thirty years ago, through the study of songbirds. Each spring, male finches and canaries learn new tunes to woo potential mates. Scientists discovered that as these birds built their repertoire, they also sprouted thousands of new brain cells a day. Over the years, researchers spotted new neurons in adult rats, shrews, and monkeys as well.

Skeptics still wondered whether adult humans could grow their brains. Then a breakthrough came from an unlikely source: the Cold War. In its early years countries tested their nuclear weapons regularly. Then, following the test ban treaty of 1963, they stopped. Levels of radiocarbon (14C), an isotope produced by nuclear detonation, spiked and then plummeted just as quickly. Radiocarbon makes its way into the plants and animals we eat, and what we eat makes its way into new cells we produce. Neuroscientists such as Kirsty Spalding took advantage of this. Borrowing from archaeologists, Spalding “carbon-dated” brain cells based on their levels of 14C, tagging the year they were born. Surprisingly, she found that people grow new neurons throughout their lives.

In other words, the brain is not hardwired at all. It changes, and these shifts are not random. MRI studies have now repeatedly shown that our experiences, choices, and habits mold our brains. When people learn to play stringed instruments or juggle, parts of their brain associated with controlling their hands grow. When they suffer chronic stress or depression, parts of their brain associated with memory and emotion atrophy.

Over the years, fixism has sprung other leaks. The more scientists looked for an unchanging “human nature,” the less evidence they found. Consider intelligence. Francis Galton claimed it was baked into us at birth, never to budge. But a century later, in 1987, the psychologist James Flynn discovered a startling trend: Over the previous four decades, the average American’s IQ had shot up by fourteen points. Other researchers have documented similar effects around the world in the years since. Crucially, intelligence changes even across generations of the same families. Such shifts are almost certainly not genetic in origin and instead reflect new choices and habits—for instance, in nutrition or education. Consistent with this idea, poor children who are adopted into more well-off households see their IQs rise by more than ten points. And in a recent analysis of over six hundred thousand people, psychologists found that for each year of schooling a person completed, their IQ increased by about a point, effects that last throughout their life.

Our personalities also change more than we might realize. After leaving home, new adults grow more neurotic. After getting married, they become more introverted; after starting their first job, they become more conscientious. We can, of course, also change intentionally. Psychotherapy leaves people less neurotic, more extroverted, and more conscientious than they were before—and these changes last at least a year after therapy ends. Personality doesn’t lock us into a particular life path; it also reflects the choices we make.

THE SCIENCE OF human nature can now take a page from geology and finally reject fixism. We’re not static or frozen; our brains and minds shift throughout our lives. That change might be slow and imperceptible. And yet we move.

In a nod to Wegener, we might call this idea “psychological mobility.” Mobility doesn’t mean anyone can be anything. Try as I might, I’ll never move objects with my mind or win a Nobel Prize in physics. Our genes absolutely play a role in determining how smart, neurotic, and kind we are, and there’s no denying that they’re fixed at birth. Human nature is part inheritance and part experience; what’s up for debate is how much each part matters.

Consider intelligence. A person’s genes might predispose him to be relatively high or low in smarts. We can call this their “set point.” But each person also has a range. Their intelligence registers as higher or lower depending on who raises them, how long they go to school, and even the generation into which they are born. A fixist focuses on a person’s set point, asking how smart a person is. A mobilist focuses on ranges, and asks how smart that person can be. Both of these questions are important, but fixism has dominated more conversations about human nature than it deserves. As a result, we’ve underestimated our power over who we become.

According to the Roddenberry hypothesis, empathy is a trait, locked away and impervious to our efforts. This idea jibes with common sense. Of course some people care more than others; that’s why we have saints and psychopaths. But what do these differences mean?

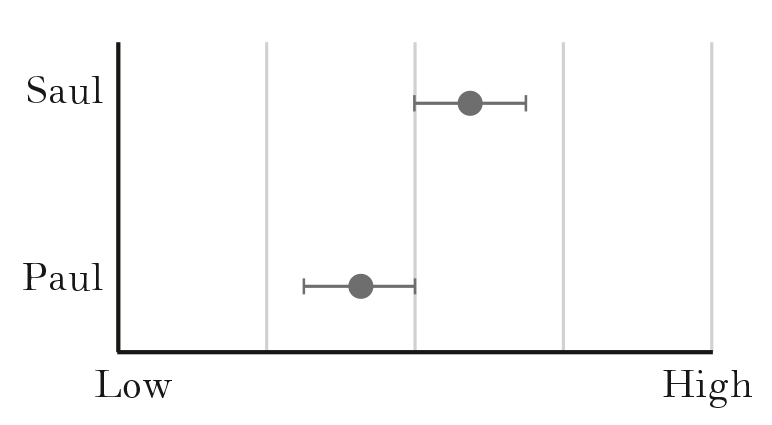

Imagine two people: Saul and Paul. Paul is less inclined toward empathy, more toward selfishness. A fixist would argue that this will hold true forever, because people seldom depart from their set point. Here, that idea is depicted by both men having a relatively narrow range. Even on his best day, poor Paul can barely empathize as much as Saul on his worst:

This perspective has some truth to it. Empathy is at least somewhat genetic, as demonstrated by studies of twins. In some of this research, twins decipher people’s emotions based on pictures of their eyes; in others, their parents report on how often each twin shares her toys with other kids. In one particularly creative experiment, researchers visited two-to-three-year-old twins in their homes. One scientist pretended to accidentally slam her own hand in a briefcase. A second secretly measured how concerned children became and how much they tried to help their injured visitor.

No matter what the measure, identical twins tend to be more similar than fraternal ones. Both types of twins share a household, but identical twins share all their genes instead of half. The extent to which they “look” more alike than fraternal ones—in their personality, intelligence, and so forth—is what scientists chalk up to heredity. Analyses like this suggest that empathy is about 30 percent genetically determined, and generosity closer to 60 percent. These effects are substantial—comparable to IQ’s genetic component of around 60 percent. And they are stable. In one study, people completed empathy tests several times over twelve years. If you knew a person’s score at twenty-five, you’d do a decent job predicting how they’d perform at thirty-five.

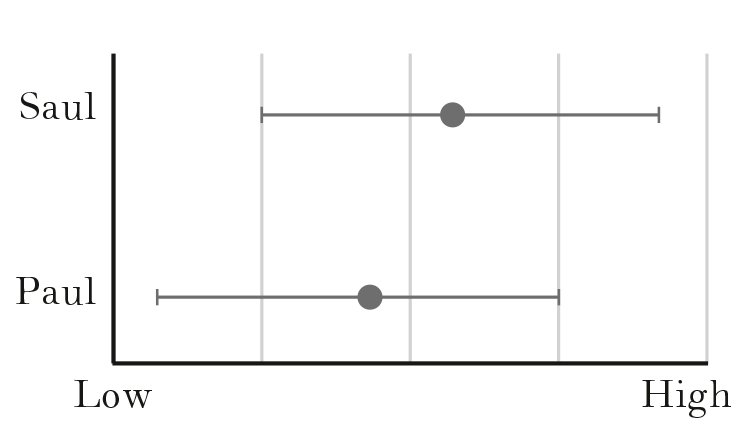

While granting the importance of set points, a mobilist would argue that people can still change in meaningful ways. Take another look at the twin research we just discussed. Yes, empathy and kindness are partially genetic, but there is still room for non-genetic factors—experiences, environment, habits—to play a crucial role. Here, that elasticity is depicted by increasing the range of Saul and Paul’s possible empathy. Depending on their experiences and choices, each one can travel quite a distance along his range. In this formulation, even if Paul’s set point is lower than Saul’s, his most empathic moments will surpass Saul’s least:

We now have decades of evidence demonstrating that empathy is shaped by experience. One-year-old children whose parents express high levels of empathy show greater concern for strangers as two-year-olds, are more able to tune into other people’s emotions as four-year-olds, and act more generously as six-year-olds when compared to other children their age.

Nurture matters even more for children at the greatest risk. Psychologists have examined orphans in Romania, a country infamous for its maltreatment of institutionalized children. Kids here were often underfed and neglected. Never having been cared for, many Romanian orphans never learn to care about others, and display empathic deficits similar to those found in psychopaths. Some orphans, though, are lucky enough to be adopted by foster families, typically at two years of age. These children are spared many of their peers’ problems, developing typical levels of empathy—especially if their foster parents respond warmly to them. A cruel environment moved these children to the left of their range, but swapping in a kinder one brought them back.

Circumstances mold empathy well into adulthood. A bout of depression, for instance, predicts that a person will become less empathic over the following years. More acute suffering also shifts empathy, in surprising and varied ways. When people cause it, their empathy erodes; when people endure it, their empathy grows.

We can’t always avoid inflicting pain on others. Oncologists are constantly delivering unwelcome news: a patient’s cancer has worsened; his treatment has failed; this illness will end her life. In 2017, U.S. managers laid off about thirty-four thousand employees a month. The psychologists Joshua Margolis and Andrew Molinsky call these moments “necessary evils.” It’s easy to sympathize with cancer patients and the newly unemployed, but people who carry out necessary evils suffer as well. For instance, about 50 percent of oncologists report feeling intense heartbreak and stress every time they break bad news. In laboratory experiments, even pretending to do so drove up medical students’ heart rates.

When someone suffers at your own hands, caring for them can quickly give way to despising yourself. The resulting guilt takes a toll. During periods of heavy layoffs, managers who swing the ax develop sleep and health problems. In situations like these, people protect themselves by removing emotion from the equation. Margolis and Molinsky found that about half of individuals who performed necessary evils pulled away from the people they harmed. During layoffs, managers avoided thinking about their employees’ families. They used curt language and cut off conversations. Doctors who had to deliver bad news focused on the technical side of treatment, trying to elide patients’ pain.

To live with themselves, people who harm others often blame or dehumanize their victims, a process known as “moral disengagement.” In the 1960s, one group of psychologists asked subjects to shock another person repeatedly. The subjects reacted by denying that the shocks hurt, and even thinking of victims as less likable. In a more recent study, white Americans were asked to read about the massacre of Native Americans at the hands of European settlers. Afterward, they doubted that Native Americans could feel complex emotions such as hope and shame.

Disengagement builds emotional calluses. For decades, the psychologist Ervin Staub has studied individuals who kill during war or genocide. He finds that they turn off their empathy, “reducing [their] concern for the welfare of those [they] harm or allow to suffer.” In 2005, researchers interviewed death workers at prisons in the American South. Consistent with Staub’s view, executioners claimed that death row inmates had “forfeited the right to be considered full human beings.” Workers who were most involved in killing—for instance strapping inmates to gurneys for injections—dehumanized them the most. The closer executioners came to their victims, the less they saw them as people.

Causing pain can move people to the left of their empathic range, making caring harder, but people who endure great suffering often become more empathic as a result. Traumas—including assault, illness, war, and natural disaster—are psychological earthquakes that rock the foundations of people’s lives. Survivors see the world as more dangerous, crueler, and less predictable after trauma than they did before. Many suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder: overtaken by flashbacks of their worst moments, fighting uphill to get their lives back. But most people who endure trauma do not develop PTSD. Six months after the fact, less than half of sexual assault victims report symptoms; among combat veterans, that number is about an eighth.

Trauma survivors who are supported by others typically have an easier path to recovery. Afterward, they often turn around and play that role for others. After Hurricane Harvey struck Houston, a group of Katrina survivors known as the “Cajun Navy” hauled dozens of boats to Texas to help recover victims. Thousands of other trauma survivors have switched careers to become “peer counselors”—helping others heal from wounds they once suffered. Veterans talk each other through hopeless moments. Addicts who have been clean for ten years help others make it through the first ten days.

Psychologists call such kindness “altruism born of suffering,” and it is everywhere. Researchers recently examined war-torn communities in more than forty countries, including Burundi, Sudan, and Georgia. People in these towns, villages, and cities underwent unthinkable pain, and could be forgiven for retreating from public life. Instead, they redoubled their commitment to social movements and civic engagement. When researchers gifted them with money, they were more likely to share it with each other than people in unaffected towns. Likewise, victims of political violence and natural disasters volunteer at unusually high rates to help homeless people, the elderly, and at-risk children. And 80 percent of rape survivors report deeper empathy in the months after being attacked than they did before.

These positive effects last years. In one study, the psychologists Daniel Lim and Dave DeSteno measured the number of painful life events individuals had experienced throughout their lives—things like car accidents, severe illness, or victimization by crime. These people then came to the lab, where they met another participant who was struggling with a frustrating task. Participants stepped in to help this other person, and those who had suffered most were the most helpful, even if their painful experiences had occurred long before.

When survivors help others, they also help themselves. “Victims” are often stereotyped as weakened by trauma, but many emerge stronger and more fulfilled. “Post-traumatic growth”—including greater spirituality, stronger relationships, and a renewed sense of purpose—is almost as common as PTSD. Survivors who feel deepened empathy and act on it are most likely to report post-traumatic growth. When they counsel new survivors, they realize how far they’ve come, and how strong they are. And if the pain they endured can help them help others, it was not for nothing. As the great psychologist and Holocaust survivor Victor Frankl writes, “A man who becomes conscious of the responsibility he bears toward a human being…will never be able to throw his life away. He knows the ‘why’ for his existence, and will be able to bear almost any ‘how.’ ”

EXPERIENCES CAN AND do move us along our empathic range, but the changes we’ve seen so far happen by accident. People don’t harm others in order to care less; they merely adapt to the choices they’ve made. Victims certainly don’t choose to be harmed; they grow kinder as a result of their circumstances. Few people choose their families, and no one chooses their genes. A second question, then, is not whether empathy can grow or shrink, but whether we can change it on purpose.

One heartening piece of evidence is that simply believing it is possible to change one’s empathy helps to make it so. I learned this from one of my intellectual heroes, Carol Dweck.

I first met Carol during my job interview at Stanford. I’m a nervous person to begin with, and that was a nervous day for me, so talking with her was enough to tip me into a low-grade panic. On my way to her office, I stopped in the bathroom, soaked paper towels in cold water, and held them to the back of my neck, hoping to slow my inevitable sweating. During our meeting I talked at a mile a minute. My big question, I said, was whether people can change how empathic they are. I told her what you’ve just read: that empathy is partially baked into our genes but also changes with circumstances.

“But what do people think?” she asked.

I was confused. I had just rattled off a tight five minutes on what scientists think. Perhaps I had been unclear? Rushed? Un-hirable? I began rehashing my summary, but Carol interrupted me.

“No, I mean what do people think? Not researchers, but the people in their studies.”

Researchers are, of course, people, too. But Carol’s deceptively simple question made me realize that I had rarely considered what non-scientists believe about empathy.

This matters, and if anyone would know why, it’s Carol. Over several decades, she has studied “mindsets,” or what people believe about their own psychology. Carol finds that people fall into two general camps. “Everyday fixists” believe that pieces of our psychology, such as intelligence and extroversion, are unchangeable traits. Fixists define people, including themselves, by their set point. “Everyday mobilists” think of these same qualities more like skills. Sure, they might have a certain level of intelligence now, but that can shift, especially if they work at it.

Mindsets affect what people do, especially when things get tough. In a famous set of studies, Carol and her colleagues first measured students’ mindsets about intelligence. Students then completed a challenging problem set, and later learned that they’d performed poorly. Fixist students attributed their failure to a lack of ability. And when they failed academically, they shied away from opportunities for extra training. To them it might have seemed pointless—if I can’t improve, why try?—and embarrassing to boot. By accepting remedial education, they were admitting they were not smart and never would be. Mobilist students, on the other hand, embraced opportunities for additional learning. They reasoned that the more work they put in, the more they’d grow.

Carol not only measures mindsets; she also changes them. She and her colleagues have students read essays suggesting that intelligence is malleable. No matter how they start out, these students become mobilists, and try harder at intellectual tasks as a result. This kind of change can produce long-term effects. In a recent review of more than thirty studies, psychologists found that people who are taught that they can become smarter end up with slightly—but reliably—higher GPAs in the following school year. Mindsets are especially powerful in bolstering the performance of minority students and, in some cases, decreasing racial achievement gaps.

Once I arrived at Stanford, Carol and I—along with our colleague Karina Schumann—decided to see whether empathy might work in a similar way. We reasoned that people who believed it was a trait would avoid it during tough moments. People who believed it was a skill, on the other hand, might dig in, trying to empathize even when it was hard.

We began simply, by asking hundreds of people to pick which one of these statements they agreed with:

In general, someone can change how empathic a person they are.

In general, someone cannot change how empathic a person they are.

Our participants were split down the middle, about half fixists, half mobilists. With this information in hand, we ran them all through an empathic obstacle course: a series of circumstances in which empathy often fades. In most cases, mobilists tried harder than fixists. For instance, they spent more time listening to emotional stories told by someone of a different race, and said they would devote more energy to considering the opinions of someone on the other end of the political spectrum.

Carol, Karina, and I also changed people’s view of empathy, by presenting them with one of two magazine articles. Both started with the same passage:

Recently, I bumped into someone I went to high school with over 10 years ago. As with all post–high school encounters, I couldn’t help but compare the person in front of me to the person I remembered. Mary was one of those unsympathetic types who didn’t really ever put herself in other people’s shoes or understand how other people felt.

The fixist article continues:

Can you imagine my lack of surprise to find that she is now a mortgage lender who sometimes repossesses the homes of struggling homeowners? Meeting such a similar person now, I wondered why Mary hadn’t changed—why hadn’t she grown out of her non-empathic persona?

It goes on to describe empathy as a trait, and closes with this reflection on Mary: “I guess it’s no surprise that her level of empathy hadn’t changed over time. Even if she had tried to learn to feel empathy for others, she probably would have been unsuccessful because it is just a part of who she is.”

The mobilist article takes a different turn:

Can you imagine my surprise to find that she is now a social worker with a family and an active role in community service? Meeting such a different person now, I wondered how Mary had changed so much.

This article then describes empathy as a skill, providing evidence that people can and do grow their capacity to care. It wraps up, “I guess she worked at developing feelings of empathy over the years. Now, as a social worker, she can pass on the message to others: People can change how much empathy they feel for others.”

People in our study believed each article. After reading that empathy was a trait, they agreed with fixist statements. After reading it was a skill, they became mobilists. Crucially, these beliefs changed their own choices. “New fixists,” empathized lazily, for instance with people who looked or thought like them, but not with outsiders. New mobilists, by contrast, empathized even with people who were different from them racially or politically.

Mobilists flexed their empathy in other tough situations, too. In one study, Stanford students learned about a cancer awareness campaign on campus. We told them they could help out in a number of ways. Some of those ways promised to be breezy, for instance participating in a walkathon to raise research money. Others would be painful, for instance sitting in on a cancer support group and hearing sufferers’ stories. We asked students how many hours they’d be willing to volunteer for each. New fixists and new mobilists pledged equal amounts of time when helping was easy, but mobilists volunteered more than twice as many hours than fixists when more was required. Situations that normally turn people away no longer fazed them.

Participants were randomly selected to read either the fixist or mobilist article, meaning that those in each group almost certainly didn’t differ much from one another when they arrived at the lab. But in just a few minutes, we pushed them to the left or right of their empathic range.

This work highlights a deep irony. The Roddenberry hypothesis dominates our culture’s view of how empathy works. In essence, we’ve all been living like fixists. There are enough barriers to modern kindness, and by imposing fixism on ourselves we’ve added another one. If we can break this pattern and acknowledge that human nature—our intelligence, our personality, and our empathy—is to some extent up to us, we can start to live like mobilists, opening up new empathic possibilities. Perhaps in reading this far, you’ve moved yourself in that direction already.

But can we do more than simply change our mindset? Can we take precise control over our experience in the moment, empathizing in just the way we want, when we want to? And if so, how?