CHAPTER 2

Choosing Empathy

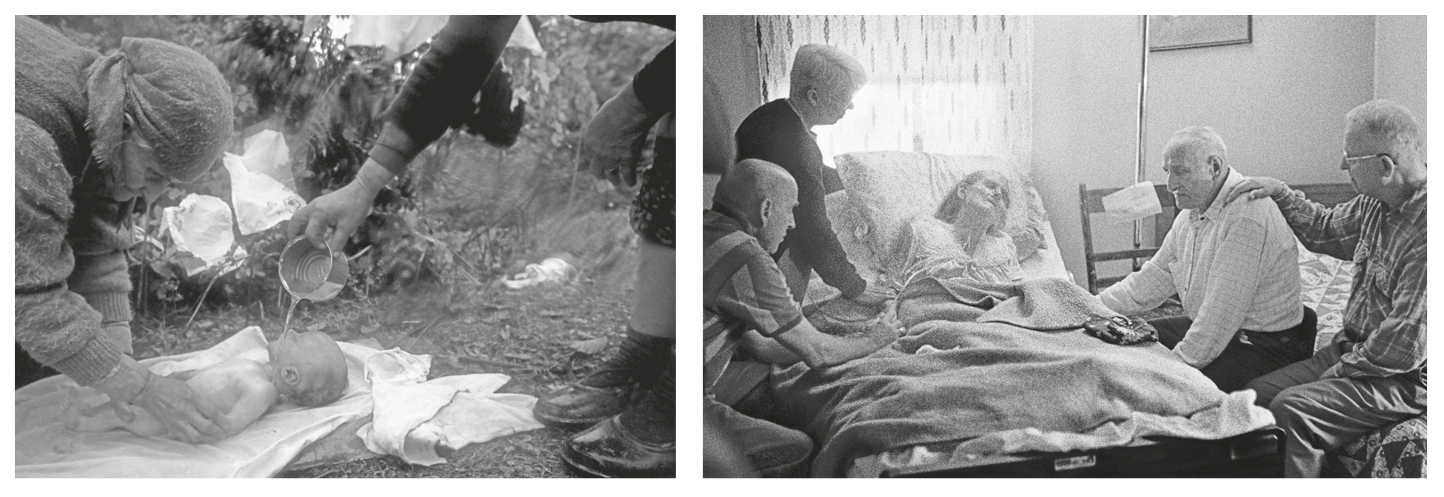

RON HAVIV AND Ed Kashi witness pain for a living. “We gravitate toward the things that most people would run away from,” Kashi reflects. For decades, these two photojournalists have documented funerals, uprisings, and everything in between. They each provide an unblinking look at their subjects’ hardest moments. But the way they approach their work is different. Consider these two photos, taken about six thousand miles and two years apart:

Haviv captured the one on the left. During the Kosovo War, Serbs carried out an ethnic cleansing campaign, wiping out or expelling Muslims. Many fled to the nearby mountains, but shelter was sparse. “This community was living in the mountains and it was getting cold,” Haviv explains, “and this child died of exposure. Here they’re preparing the child for burial, and in the Islamic tradition you wash the body before burying it.”

To capture images like this, Haviv removes his own feelings from the equation. “I have a responsibility to be there for the public, not myself…not to become so emotional that I am unable to photograph.” Surrounded by grief, he keeps a poker face.

Kashi took the photo on the right. The woman at its center, Maxine, had reached the last stage of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. “It was so clear this was the day she needed to die,” Kashi recalls. “Her husband had to tell her to let go, and it became clear that I was the one who should tell him to go do that. So, I got on my knees and said, ‘Art, I think you need to tell Maxine that it’s okay to go.’…He got up and did it, and an hour and a half later she was dead.”

Unlike Haviv, Kashi dives headfirst into his emotions. “Some of the greats would say, ‘I’m there to do my work,’ and they’re more dispassionate,” he acknowledges, “but often I’m crying a lot in these situations.” He cultivates intimate connections with his subjects. In Maxine’s last months, she and Art had slept in adjacent beds, hers provided by the hospital. The night she died, they replaced her bed with a cot; Kashi slept in it so that Art wouldn’t be alone.

Why do Kashi and Haviv work so differently? One possibility is that they can’t help it. This is the second part of the Roddenberry hypothesis: Empathy is a reflex that washes over us when we encounter someone else’s emotions. Kashi might be the Deanna Troi of photographers; Haviv might be more like Data.

Neither photographer would agree. Haviv cares enormously for his subjects. He also feels that to help them, he must stay collected enough to document their suffering. Later, when the job is done, he lets himself go. “I’ve trained myself so that I can become emotional once I’m away from the situation,” he says. “Back at the hotel, I can cry.” For Kashi, emotional connection is part of the job. “I’m almost in the role of a social worker.”

Haviv and Kashi don’t see themselves as controlled by their feelings. Each, in his own way, empathizes with purpose.

IMAGINE A TUG-OF-WAR. Two teams, red and blue, pull at a rope from either side. You could describe this event in many ways: a row of young faces and bodies contorted with effort, an ancient contest of wills, a defunct Olympic event petitioning for a comeback in 2024. A physicist could describe it differently: Each player exerts a force—a combination of their strength and the direction in which they pull. Each team’s force can be drawn as a series of arrows, with the red team’s pointed east (let’s say), and the blue team’s pointed west. Longer arrows correspond to players who exert more force, shorter arrows to those who exert less. If the total eastward force is greater than the westward force, the red team will inch toward victory. If the red team tires and the blue team rallies, these forces will shift and the tide will turn.

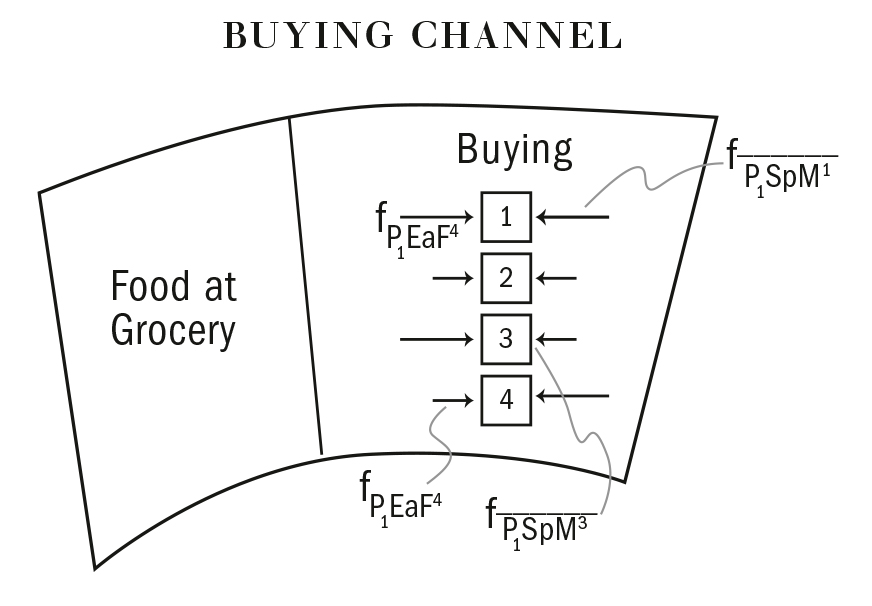

The psychologist Kurt Lewin saw human behavior in the same way. In the 1930s, Lewin built his grand theory on the principles of physics. He argued that people are governed by a set of psychological forces, or motives. We are pulled toward certain actions by approach motives, and pulled away from them by avoidance motives. If approach motives outweigh avoidance motives, we act; if not, we don’t. Here he depicts—of all things—the process of buying groceries.

The shopper encounters four foods. Lewin depicts the motives enticing him toward each—maybe it’s delicious or healthy—through a rightward arrow, and the motives pulling him away from it—maybe it’s expensive or gluten-free—through a leftward one. Food 3 has many qualities that attract the shopper, and few that repel him. Sold. Food 4 is also a no-brainer, but in the other direction. Foods 1 and 2 are trickier. Food 1 attracts and repels at the same time; maybe it’s delicious but also expensive (think filet mignon). Food 2 is not much of either, for instance, cheap but bland (maybe bologna). Both make for difficult choices: Food 1 because of conflict, Food 2 because of apathy.

Lewin used this theory to explain peer pressure, political turmoil, and everything in between. According to him, each choice reflects a tug-of-war in your mind. Everything you do, from getting out of bed to reprimanding your child to going for a jog, happens because the forces pulling you toward that action defeated the forces pulling you away from it.

What about how you feel? Until recently, most scientists didn’t think of emotions as the result of a Lewin-style push and pull, or as choices at all. In 1908, the psychologist William McDougall argued that feelings were “instincts”: ancient and preprogrammed. According to him, you don’t decide when you feel fear, lust, or rage, any more than you choose whether your knee jerks when it’s tapped with a mallet. Many people today agree with him. Researchers recently asked more than seven hundred people how they thought emotions work. About a third of them agreed with the statement “People are ruled by their emotions.” About half believed that “emotions make people lose control.”

McDougall also saw empathy as an instinct, triggered automatically by other people’s feelings. “Sympathetic pain or pleasure,” he wrote, “is immediately evoked in us by the spectacle of pain or of pleasure….We then act on it because it is our own pain or pleasure.” This view lives on in the Roddenberry hypothesis.

McDougall believed our empathic instinct was a positive force, the “cement that binds animal societies together.” But a darker view has prevailed for centuries. In 1785, Immanuel Kant wrote that “good natured passion is nevertheless weak and always blind.” In other words, even our most positive reflexes are still reflexes, and we can’t determine when they’re triggered. Empathy fires in response to a friend’s pain, but not a stranger’s. It fires in response to people who look like us, but not outsiders; to pictures, not statistics.

According to some, this is empathy’s fatal flaw. Paul Bloom, a psychologist and the author of Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion, writes, “Empathy’s narrow focus, specificity, and innumeracy mean that it’s always going to be influenced by what captures our attention, by racial preferences, and so on” (italics mine). When it misfires, we are helpless to redirect it: It is doomed to be biased, shortsighted, and ill-suited to the modern world. Bloom believes that to become truly moral beings, people must give up on feeling altogether, replacing it with a more Data-esque, rational benevolence. As he writes elsewhere, “Empathy will have to yield to reason if humanity is to have a future.”

But, of course, feeling and reason are in constant dialogue. Emotions are built on thought. Someone who sees a bear might feel curiosity or terror, depending on whether he’s at the zoo or in the woods. A child who falls down looks to her parents. If they respond calmly, she bounces back up; if they panic, she dissolves into a puddle of tears. Emotions reflect not just what happens to us, but how we interpret those things. The Stoic Epictetus knew this, and so did Shakespeare. As Hamlet puts it, “There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.”

This has a powerful consequence: By thinking differently, we can choose to feel differently. My colleague James Gross has examined this phenomenon for more than two decades. In dozens of studies, he’s shown people emotional images like the ones at the top of this chapter. He asks subjects to turn down their feelings (like Haviv) or turn them up (like Kashi) by rethinking what they see. While looking at Maxine on her deathbed, someone might ramp up their sadness by thinking of Art, drinking coffee the next morning, without her for the first time in fifty years. Someone who wants to feel less sad might instead focus on the love they shared. After detaching, people in Gross’s studies report weaker emotions. Their bodies show fewer signs of stress, and parts of their brain associated with emotional experience calm down. After they ramp up their feelings, the opposite happens.

This is one form of what I call “psychological tuning”—the quick, agile ways we alter our experience, for instance by focusing intently on a math problem, or rethinking what we feel. Tuning helps us constantly, especially in heated situations. Spouses who rethink their emotions during spats are more satisfied in their marriage. Israelis who do the same while reading about Palestinians’ actions in Gaza advocate for more peace-positive policies.

People can choose not just to turn their emotions up or down but also to cultivate particular feelings that are useful in the moment. Happiness won’t help a boxer going into the ring, but anger might. For a beggar seeking others’ sympathy, sadness is wiser than fear. The psychologist Maya Tamir has found that people gravitate toward handy emotions, even when they feel bad. In her studies, people choose angry music to psych themselves up before a hostile negotiation, but sad music before asking for a favor. Emotions really do work like Lewin’s tug-of-war: Whether you realize it or not, you’re constantly weighing the costs and benefits of sadness, or joy, or anxiety, and choosing the feelings that serve your purpose.

Empathy is no different. Yes, it can occur automatically, like McDougall suggested. But more often, we choose or avoid it depending on whether it seems useful. There are obvious reasons to choose it. For one, it can feel good, because positive emotion is contagious. We are lifted up by the happiness around us like race cars drafting off one another’s momentum. Empathy also feeds our deep-seated need for relationships. During my childhood, it was a way to feel closer to my parents amid family turmoil, so I worked at it. Likewise, when people want to connect—for instance, when they’re around attractive or powerful individuals—they turn up their empathy and read others more clearly as a result.

Even when empathy doesn’t feel good, we know it can make us look good. If Mother Teresa, the Dalai Lama, or Jesus are any indication, compassion and generosity are the clearest signs of virtue. When people must establish their moral bona fides, they turn to empathic actions. Individuals are more generous in public than in private, and also act kindly to convince themselves of their own goodness. In several studies, psychologists have put people under “moral threat,” for instance, asking them to remember times they betrayed someone else’s trust. To compensate, these participants help strangers, donate to charity, and advocate for environmentally friendly behaviors more than people who were not threatened.

But for every reason to choose empathy, there is another reason to avoid it. When others are in pain, connecting with them risks our own well-being. One friend of mine, who is a therapist, does her best not to schedule depressed patients for the end of the day, to avoid bringing their darkness home with her. In the 1970s, the psychologist Mark Pancer tested whether people would literally steer clear of painful empathy. He positioned a table in a busy student union at the University of Saskatchewan, posted information about a charity on it, and tinkered with its appearance. Sometimes the table was unmanned; other times a student sat by it in a wheelchair. Sometimes it contained an image of a smiling, healthy child; other times it showed a sick, sad one. The wheelchair and the sad image were triggers for empathy. Pancer found that students walked in a wider arc when it contained empathy triggers than when it didn’t, keeping difficult feelings at bay.

When our own time or money is at stake, empathy feels like even more of a burden, and we avoid it more forcefully. A New Yorker walking the streets of Manhattan is inundated with suffering and need. If he takes it all in, he ends up in a double bind. He can give to others until he has nothing left, or live with the guilt of not giving. People often avoid empathy in situations like this. In one study, people who believed they’d later have a chance to donate to a homeless person avoided hearing a version of his story that included emotional details. It’s not that they couldn’t feel for him; they actively chose not to.

Even otherwise caring people become callous when they feel overwhelmed. The psychologists John Darley and Dan Batson once asked Princeton seminary students to prepare a sermon on the biblical parable of the Good Samaritan. It tells the story of a man traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho who is robbed, beaten, and left for dead by criminals. Luckily, a resident of Samaria later stumbles upon him. As described in the book of Luke, the Samaritan “had compassion, and went to him and bound his wounds, pouring on oil and wine…and took care of him.” You might not want to actually treat wounds with wine, but seminarians still got the story’s point and wrote about the power of caring.

Darley and Batson then instructed them to walk to another building to deliver their speech, but they added a twist. They told some students that their sermon would not begin for a while, and that they could take their time. Others learned time was tight. Students ambled (or sprinted) across Princeton’s manicured grounds, and as they reached the building, encountered a man slumped in a doorway. As the students neared him, he coughed and groaned. In fact, he was an actor, secretly recording how they responded. Over 60 percent of them helped when they were in no hurry, but only 10 percent did when they felt rushed. The irony here is palpable: Students wouldn’t help a man lying on a sidewalk because they were in too much of a hurry to give a speech about how important it is to help a man lying on a sidewalk.

People who avoid empathy often hurt themselves in the process. Decades of evidence demonstrate that individuals who empathize with others also help themselves: attracting friends more easily, experiencing greater happiness, and suffering less depression than their less empathic peers. When someone decides they don’t have the resources or energy for other people, they deprive themselves of those benefits. In one study, the psychologist John Cacioppo and his colleagues surveyed people annually for ten years. Individuals who were lonely in a given year reported being more self-centered the following year. Self-centeredness, in turn, predicted deeper loneliness and depression in the future. Lonely individuals’ motives were off base—empathy felt like it would overwhelm them, so they focused on themselves and ended up worse off.

BORROWING FROM LEWIN, we can see the problems of modern kindness in a new light. When empathy evolved, humans were enmeshed in close relationships. We had reason to care about almost everyone we saw. These forces pulled us toward empathy and made it easy. Now we are isolated, stressed, and drowning in animosity. We have more reasons to avoid empathy than ever.

Restating a problem is not the same as solving it. But in this case, it offers some ideas. Lewin famously wrote, “There is nothing so practical as a good theory.” Describing water currents is an academic exercise; diverting them to irrigate crops is a technological revolution. Likewise, when we understand the forces on either side of a mental tug-of-war, we can tip its balance.

Lewin, who was Jewish, fled Germany for the United States in the 1930s and began working tirelessly on what he called “action research.” Rather than staying in the lab, he sought out real-world problems, diagnosing the psychological forces that caused them and devising tweaks to encourage wise, healthy, or productive choices. One of his first cases was Harwood Manufacturing, a textile company that had recently moved its operations from New England to the tiny Appalachian village of Marion, Virginia. Harwood had trouble recruiting skilled factory workers to its new location, so the company hired new ones: mostly young, inexperienced women from the surrounding mountains. Supervisors trained them for twelve weeks, then pushed them to work as quickly as possible. To gin up motivation, they offered large, competitive bonuses for fast workers and heaps of criticism for slow ones.

It was a dismal failure. Virginians worked at half the rate of New Englanders and turned over twice as often. Many quit before their training even ended. Lewin realized that this reflected a toxic tug-of-war. Yes, money motivates people, but workers in Marion were already earning much more at Harwood than they would at any other job in the area. For them, bonuses were a weak psychological pull. By contrast, rushing to outpace their neighbors had real drawbacks—anxiety, fatigue, and hostility.

Lewin realized that he could realign these forces by swapping out competition for cooperation. He organized a new type of training. Instead of a company-wide focus on individual performance, groups of new Harwood employees held informal meetings and together settled on a reasonable rate of production. This system shifted their motives. Workers had chosen their target, rather than having it forced on them. Productivity meant camaraderie, not isolation. Lewin’s strategy worked: Democratically organized teams not only produced more; their morale shot up as well.

Over the years, Lewin used action research on countless problems—from food choices to race relations. Generations of scientists have taken up his mantle, by making good decisions easier. Some of these techniques are called “nudges”: small, subtle changes to a person’s situation that inspire big changes in their actions. For instance, when a company makes retirement saving the default option for new employees, about twice as many workers save money than when they have to actively choose it. In countries where organ donation is the default, more than 80 percent of people sign up; in countries where it is not, that number is closer to 20 percent. Nudges increase college enrollment, energy conservation, voting, and vaccination rates, often much more efficiently than other policy strategies.

A growing number of psychologists have used similar approaches to help people choose empathy, even when they might avoid it. Empathy builders take Lewin’s lead. As we have in this chapter, they first diagnose the forces in empathy’s psychological tug-of-war. Then they alter them—amplifying empathy-positive forces, diminishing empathy-negative ones, or both.

After dismantling seminary students’ empathy, Dan Batson spent the rest of his career showing he could rebuild it just as quickly. In one particularly clever study, Batson flipped compassion collapse on its head. This was the late twentieth century; the AIDS epidemic was roaring. So was the stigma surrounding its victims, who were often blamed for their illness or treated as radioactive. Thousands were suddenly afflicted, yet many Americans didn’t know them. The victims were statistics, and strangers—two big reasons not to empathize.

Batson knew that people naturally care about single individuals and their stories. Could he leverage that to get them to empathize with a whole group? To test this, he played University of Kansas students a recording of Julie, a young woman living with HIV, who describes the illness’s toll:

Sometimes I feel pretty good, but in the back of my mind it’s always there. Any day I could take a turn for the worse. And I know that—at least right now—there’s no escape….I feel like I was just starting to live, and now, instead, I’m dying.

All the students in Batson’s study heard Julie, but he encouraged some of them to listen to her. “Imagine how the woman who is interviewed feels about what has happened and how it has affected her life,” their instructions read. Unsurprisingly, this prompt increased people’s empathy for Julie. But, more important, participants who imagined how Julie felt also came to care more about other people living with HIV or AIDS. They were more likely to agree with statements such as “Our society does not do enough to help people with AIDS,” and reject victim-blaming claims such as “For most people with AIDS, it is their own fault that they have AIDS.”

Empathic nudges can be shockingly simple. One of the simplest—if also one of the most cynical—is to pay people for thinking about one another. My favorite research using this technique answers a question I get quite often: Are women more empathic than men? The stereotype runs deep, and women do exhibit more empathy than men in many studies. According to the Roddenberry hypothesis, these differences are here to stay: an eternal Venus-Mars problem. But maybe instead of being incapable of empathy, men are merely uninspired to work at it. If that’s the case, the right incentives should change their behavior.

In one set of studies, men and women viewed videos of people telling emotional stories and then guessed how the speakers felt. Men performed more poorly than women. But in a follow-up, researchers told viewers that they’d be paid for accurately understanding speakers. This eliminated the empathic gender gap. A few years later, a separate research team told heterosexual men that women found “sensitive guys” attractive. Men who learned this eagerly turned up their empathy—the emotional equivalent of someone sucking in his gut as a fetching stranger walks by.

In addition to being hilarious, this second study demonstrates that incentives come in many forms. Money works, but so do sex appeal, social connection, and pride.

Other nudges seek to help us overcome tribalism. Sure, we typically care more for people in our group than for outsiders. But who counts as part of our group? People contain multitudes—you might be a woman, an Ohioan, a cellist, and an anesthesiologist. Each part of you carries with it a different definition of your group, and some of our “selves” are more inclusive than others. If I think of myself as a Stanford-ite, UC Berkeley becomes a bitter enemy; caring about its students (or football team) becomes an uphill struggle. But if I focus on being a California academic, Berkeley professors become part of my tribe—worth my time, attention, and empathy.

One clever set of studies leveraged this idea amid one of the most bitter conflicts in the known world: British soccer fandom. Psychologists recruited avid fans of Manchester United. Fans wrote about what ManU meant to them, and were told they would record a short video tribute to their team in another building. Then, in an echo of the Good Samaritan study, participants crossed paths with a jogger (actually an actor) who twisted his ankle and fell to the ground. In some cases, he wore a ManU jersey; in others, he wore the colors of Liverpool—ManU’s most hated rival at the time—and in still others he wore a plain jersey. Over 90 percent of participants stopped to help fellow ManU fans, but if the jogger wore a Liverpool jersey, 70 percent of them walked right by him as he writhed in pain.

This is classic tribalism, and yet a simple nudge made it disappear. In a follow-up, the researchers asked participants to write not about ManU, but instead about why they loved soccer. Again, they set out across campus to record their videos, and again they ran across a jogger in trouble. This time, though, they helped Liverpool fans almost as often. Joggers with plain jerseys were still left behind, so a second message of this work is that if you need others’ help, you’re probably better off belonging to any tribe than to none.

This research demonstrates that the right psychological pull can make empathy win out. But then again, most of these studies were conducted with college students—perhaps a relatively empathic bunch already. Maybe Klansmen, criminals, and psychopaths are just meaner. Psychopaths are particularly challenging: They can figure out what others feel, but they simply don’t care and so use their social savvy to manipulate and harm others. Society often writes such people off as incapable of change; even the way they’re punished reflects this perspective. Psychopathic—as opposed to non-psychopathic—criminals are more likely to be killed by the state, even though it’s not clear they actually reoffend more often. The thinking seems to be that there’s no hope for them and that the rest of us would be better off without them.

Making psychopaths care is perhaps the hardest possible test for empathic nudges. A few years ago, the neuroscientist Christian Keysers and his colleagues traveled to prisons around the Netherlands to try it. They scanned the brains of psychopathic and non-psychopathic criminals while showing them images of people in pain. Unlike most people, psychopaths didn’t show a mirroring response. That supports the fixist story: Psychopaths’ lack of empathy is “hardwired” into their brains. But Keysers’s team ran a second version of the study, this time taking a page out of Batson’s book. They asked psychopaths to focus on victims’ pain and to do their best to imagine how it felt. When psychopaths did this, their brains mirrored suffering in almost exactly the same way as non-psychopaths.

If psychopaths can turn their empathy up, surely the rest of us can, too. But do these changes really change us? Mobilists describe the mind as a muscle: Just as we can become stronger through exercise, the right practices can grow our intelligence or shift our personality. But muscle comes in more than one form. Some fibers—known as fast-twitch—are thick, powerful, and quick to tire. They allow you to sprint, squat, and lift weights, but not for long. Slow-twitch fibers are thinner and weaker but more durable, supporting extended effort, such as marathon running.

Dan Batson, Christian Keysers, and other psychologists produce fast-twitch changes in empathy. They shift people’s motives, encouraging them to tune toward empathy. The effects of their prompts might last a minute or an hour, but they are unlikely to endure. Hopefully, seminary students do not constantly feel rushed and can find time to help people in need. On the other hand, most of us do not have the energy to think deeply about everyone we run into. And without being prompted to imagine someone else’s situation, psychopaths will likely go on being callous. Unusual situations push people along their empathic range, but in the absence of prompts, they might slide right back to their set point.

A larger goal would be to build slow-twitch empathy: not just moving people to the right of their range, but helping them stay there. This would take more than one instance of psychological tuning—the same way that it takes more than one jog to strengthen our hearts and lungs. It requires chronic, repeated experiences, the type that spur psychological mobility. As we’ve seen, these sorts of tectonic shifts can happen—if you’re born into a nurturing family, or if you experience great adversity—but can they be designed? Few scientists have tried. Even attempting to do so would require enormous amounts of time, labor, and money—and there’s no guarantee it would work. But if we are to fight for kindness, we should first establish that the fight can be won.

A team at Germany’s Max Planck Institute, led by Tania Singer, recently provided a dramatic answer to that question. Singer is one of the neuroscientists who first put brain mirroring on the map. In the early 2000s, she recruited romantic couples to her lab and scanned one of them using MRI while they and their partner took turns receiving electric shocks. Participants activated the same parts of their brain when they felt pain and when the person they loved did. Not only that, but more empathic people exhibited stronger mirroring. This convinced much of the scientific community that some people do simply care more than others, a difference that lives deep in their brains.

But Singer herself never believed that. While earning her PhD, she had researched neuroplasticity and knew that just because something occurs in the brain, that doesn’t mean it’s fixed. She made contact with Buddhist monks who thought of empathy as anything but hardwired. In their traditions, compassion was work, and many of them practiced it for hours every day.

For the second act of her career, Singer decided to test whether these ancient techniques could tune people’s brains for kindness. She amassed more than seventy researchers and teachers for a wildly ambitious project. In a two-year period, they ran roughly three hundred participants through thirty-nine weeks of intensive training. In three-day-long retreats and daily guided practice, students honed their meditation skills. They learned to sharpen their attention and carefully notice their breathing and the sensations in their bodies.

They then trained that focus on others. In metta, or loving-kindness meditation, students focus on their desire to alleviate suffering and increase well-being. They wish goodwill first on themselves, then friends and family—easy empathic targets. Metta then requires them to stretch this warmth toward strangers, people they dislike, and eventually all living beings. Singer’s group paired students up to practice empathy together. In each pair, “speakers” shared emotional stories, and “listeners” practiced metta toward speakers. Then they switched roles and started over. Through a smartphone app, pairs came together almost every day to practice together.

Singer and her team carefully measured students’ experiences before, during, and after training. What they discovered was striking. Over time, students found it easier to pay attention for long periods—a rare skill in our information-addled age. They described their own emotions in more nuanced terms and pinpointed others’ feelings more accurately. Training was the emotional equivalent of wearing glasses for the first time: The world became more vivid, full of details they never knew they’d missed. They also acted more generously and found it easier to recognize their common humanity with others, even people very different from themselves. When encountering others in pain, students felt a greater desire to help than they had before.

The changes didn’t stop there. Singer and her team scanned students with MRI before and after training. They examined not just their empathic physiology—how students’ brains reacted to other people—but their anatomy as well: the shape and size of their cortex. Remarkably, they found that empathy-related parts of the brain grew in size after kindness training. As we’ve seen, the brain changes in response to the skills we learn and the habits we pick up. But Singer’s team showed for the first time that through purposeful effort, people can build long-term empathy and, in the process, change their biology.

SINGER’S PROJECT IS a proof of concept: It shows that we can build slow-twitch empathy—moving ourselves along our range and changing our brains. But it’s hard work. Most of us would like to get in better shape but are not in the mood to run ultramarathons. The Singer program requires weekend-long retreats and daily practice for as long as a full-term pregnancy. It’s Olympic training when most of us can only spare a few trips to the gym.

Is there a less demanding way to encourage empathy that lasts? One possibility comes from changing people’s beliefs. Carol Dweck teaches people that they can grow—become smarter, more open-minded, and more empathic. This causes them to work harder in the moment, persevere in the face of challenges, and notice their own strength. But mindsets, for instance about intelligence, can also produce slow-twitch change by turning into self-fulfilling prophecies. People who believe in themselves do things that give them even more reason to believe. They adopt habits of mind that work over the long term.

Building on these ideas, my graduate student Erika Weisz recently set out to see whether a similar approach can encourage long-term empathy. She recruited brand-new Stanford freshmen and asked them to complete a “pen pal study.” Some students read a note from a high schooler who had moved to a new state and was having trouble making friends. We asked them to write an encouraging response. In particular, we taught freshmen that empathy is a skill that people can build—using some of the same evidence you’ve read about—and that their high school pen pal could use this to make new connections. Other freshmen read a note from a high schooler who was having grade troubles; they were told to persuade their pen pal that intelligence is malleable.

Students asked to write about empathy got the message. One wrote, “I know it seems hard to be social, be vulnerable, and exercise empathy. It may feel like you are simply unable to connect with certain people, but studies have shown that…with effort and practice you can mold your empathy.” Another counseled, “Empathy is like a habit or a skill we can learn and practice for improvement, much like reciting vocabulary over and over again or practicing in sports.” A third closed their letter, “Remember that your ability to connect with people is entirely up to you. With just a little effort put forth, you can make friends. Go do it!”

We really did send these students’ notes to younger kids (more on this later), but this study wasn’t actually about changing high schoolers’ minds. Research demonstrates that when people try to convince someone else of something, they often convince themselves in the process. Erika and I used this as a back door to changing college freshmen’s mindsets, encouraging them to adopt a mobilist view of empathy.

The exercise stuck. Two months later, students who had written that empathy is a skill continued to believe it. Remarkably, it also appeared their empathy really had grown. They were better at decoding other people’s emotions than students who had written about intelligence. And in the crucial first months of college, students who wrote about empathy as a skill reported having made more close friends than their peers.

Our results are preliminary, and they need to be confirmed by future studies. But they make a promising point. Erika’s intervention was much simpler than Singer’s, and required only a few hours from our participants. And yet it produced at least some lasting change. This suggests that we can build empathy pretty efficiently. People can change how they approach everyday situations—the stories they hear, the people they meet, and the technology they use. The right tweaks make caring come naturally, turning an uphill climb into a downhill stroll.

Throughout the rest of this book, we’ll explore these strategies. Like Lewin, we’ll leave the lab and meet people where they are. We’ll encounter individuals lost in the depths of hatred, isolation, and stress: pushed away from empathy by their own pain, by their jobs, by their phones and televisions, by the systems around them. Against the odds, they find ways to connect, building empathic habits, overcoming division, and becoming kinder people.

Their experiences point the way for the rest of us. The modern world might diminish empathy. But rather than accepting this, we can identify the forces that make it happen and push back against them.