January 1863

On the morning of the 5th of January, 1863, Burch and I started in command of 200 men intending to make a more extensive expedition than usual into Arkansas.1 On that day, without any incident worth mentioning, we reached Beaver Station.2 The next evening found us some 30 miles south of that place. As daylight was fading, I stopped all alone to shoot some wild turkeys that I saw going to roost on some trees not far from the road. When I overtook the command, some two miles further on, they had stopped, and were anxiously awaiting me. They had captured a small party of rebels who claimed to be the advance look-outs of Marmaduke’s army. This army consisted of 6000 fine cavalry and a pack of good artillery.3 Burch threatened to kill the men instantly if he caught them in a lie. They stuck to what they had said. He was satisfied of the truth of their story, and wished to turn back at once. I was not satisfied. What could Marmaduke be doing there in the rear of our army under Gen. Steele? The prisoners said that I could easily satisfy myself of the truth of their story by advancing half a mile further, or by remaining where we were half an hour longer. I requested Burch to have all things ready for a hasty retreat, if necessary, and I would, in person, ascertain the facts of the case. I had not gone more than two hundred yards, when, sure enough, I met a large body of men advancing, and could hear that peculiar rumbling which is produced by the trampling of many thousands of horses. I was satisfied. I hurried back. We began our retreat. We were fired upon from the rear. We did not return the fire. We only retreated a little faster.

Several times that night our rear was fired upon by the advance guard of the enemy. Although our horses were very weary, we were obliged to keep moving. A little while before daylight, we reached Beaver Station, which was held by a company of Enrolled Militia. The commander, either a traitor or an imbecile, would make no preparations for either a defense or an evacuation of the place. He professed to disbelieve our report of the approach of Marmaduke’s army.4 While we were parleying with him, firing was heard in the direction of the enemy. Leaving this wretch to his fate, we resumed our retreat. When we reached the ford of the creek below the mill dam, the enemy were almost upon us. I crossed in the rear which received a brisk but harmless fire from the enemy. After crossing the creek, we passed up a little on the right bank. This threw the mill pond between us and our pursuers. They were trying to fire across the pond at us, but their shots, falling short, only came rattling and skipping along on the smooth surface of the ice. We returned their fire and then continued our retreat.5 We had already sent a messenger with orders to change horses at every opportunity and to warn Ozark and Springfield just as soon as possible. The advance of so large a force of the enemy could not mean anything else than the capture of Springfield, at which place were vast army stores, and, for the defense of which, only a very small force had been assigned.6

After leaving Beaver Station, we were not pressed any more by the enemy. We wondered at this and asked the prisoners the reason of it. One of the prisoners replied: “Since I have commenced telling you the truth, I will continue to do so. There is a large division of this army marching by another road which unites with this road a few miles this side of Ozark. Your danger is not from those behind you. They will not be likely to crowd you. They will wish you to move slowly so as to give the other division time to reach the junction of the roads before you do. If you do not wish to be cut off by that division, you’d better crowd for Ozark, with all speed.” We did crowd, thanks to this truthful rebel, and it is well that we did so. We were only a few hundred yards in advance of the enemy approaching on the other road. They crowded us into Ozark. Orders were awaiting us there to continue our retreat right into Springfield. The balance of our battalion were all ready to retreat with us, abandoning whatever could not be carried away.7 I called a few moments at my own door to speak to my wife and children. I had to leave them behind. Our troops were now pouring across the Finley bridge. While our rear was leaving the bridge at one end, the enemy was entering it at the other. It was now dark. For a time the enemy pressed us very closely, sometimes calling upon us to stop and give up our overcoats, declaring that they were very cold and that they wanted “them overcoats d——d bad.”

When within about five miles from Springfield, the pursuit ceased. About midnight, we reached Springfield. We got no sleep; no rest. All was bustle and preparation. Old dismounted cannons were being mounted on draymens’ trucks, loyal citizens were being armed, and even the convalescent sick in the hospitals were being brought out and put on duty. After all, we had a heterogeneous force of only 800 men with which to resist a force of 6000 as fine cavalry as ever fought in a bad cause. We were pretty well fortified, however, with earth-works and rifle pits, and our men were eager to fight.8

I expected that, when daylight came on, a feint would be made in the south by the enemy’s artillery, while the real attack would be made by a charge of the main body down Wilson Creek from the east. This was certainly the proper thing for the enemy to do, and, had he done it, the result of the battle could hardly have been otherwise than in his favor. He missed his chance, however, made his real attack on the south upon our strong earthworks, and, as a result of this mistake, gave us a glorious victory. I wondered that so able a warrior as was Gen. Marmaduke should have committed so grave an error. I understand, however, that he afterwards explained the matter by saying that he was to act in concert with another force which was to attack on the east while he held us engaged on the south, and that his failure was due to the non-arrival of this other force. This gives a complexion to the affair more favorable to Marmaduke.9

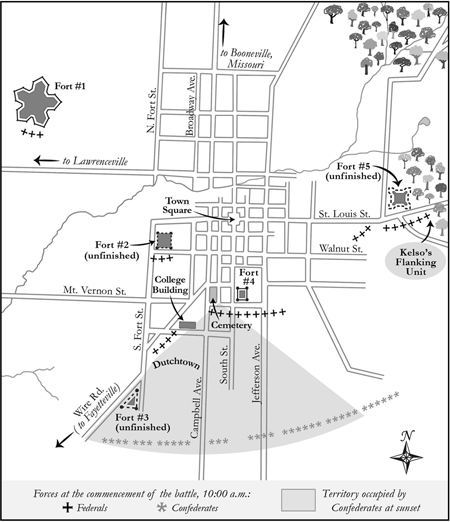

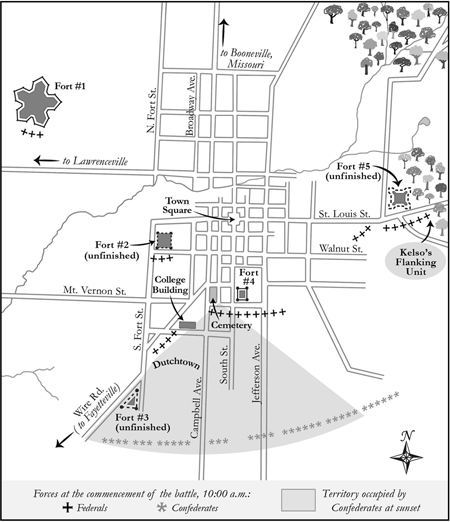

Figure 4. The Battle of Springfield, Missouri, January 8, 1863. Drawn by Rebecca Wrenn. Map sources: Based on “Plan of Springfield, Mo., Showing the Location of the Forts,” Record Group 77, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., in Frederick W. Goman, Up from Arkansas: Marmaduke’s First Missouri Raid, Including the Battles of Springfield and Hartville (Springfield, Mo.: Privately printed, 1999); Elmo Ingenthron, Borderland Rebellion: A History of the Civil War on the Missouri-Arkansas Border (Branson, Mo.: Ozarks Mountaineer, [1989]), 262; and Larry Wood, Civil War Springfield (Charleston: The History Press, 2011), 106.

I expected that the attack would be made as soon as daylight appeared. I also expected that, before opening fire upon the town, a notice would be given by the enemy to remove the women and children. It was ten o’clock, however, before we heard from the enemy, and then his first notice was in the form of several heavy shots sent crashing through our churches, our dwelling houses, our printing offices, &c. Several women and children were wounded by this barbarous fire. This fire was replied to from our earthworks, “Fort No. 4,” at the outlet of South Street. Opened thus, the battle now raged, with varying success, till the darkness of the succeeding night compelled the combatants to cease their fearful work of mutual destruction.10

Brig. Gen. E. B. Brown was in command of our forces. Believing that I was correct in my views as to the point at which the real attack was to be made, he at first sent my entire battalion to defend the rifle pits on the east; and, seeming to think that the success on that side greatly depended upon me, he advised me how to act, and how to cou[n]sel my superiors in office.11 Lieut. Col. John A. Pound commanded our battalion. I commanded an advanced flanking party of 20 mounted men. Presently, all except my little party were with-drawn from that part of the town to aid in resisting the attack, on the south, upon Fort No. 4 and upon the stockade around the college building.12 From my position on the extreme left, I could see but little of the real battle. Against me were matched 50 well-mounted rebels. With this party I skirmished all day, neither party accomplishing much except fine feats of horsemanship.13 Sometimes, the rebel party would retire to a distance of a mile from our position, conceal themselves in a depression of ground, then send half a dozen of their number close to our position to call us out. We would chase them for some distance, then, when their whole party came after us, we would turn and get away as fast as our horses could carry us. They would chase us as close as they dared to our defenses, then stop, order us to give up our “over-coats,” our “Lincoln coffee, &c.” They would also make obscene gestures, turning up their buttocks toward us and patting them with their hands.

Sometimes this party and my party would stop not far from each other and, from the higher ground which we occupied, watch the conflict that was raging a mile to the south west of us. The roar of artillery was incessant as was the rattle of musketry. We could see every movement,—the charges and the counter-charges, the shells bursting in air, the actual intermingling of the ranks at one point in a deadly struggle for a field piece. The piece belonged to us; it soon belonged to the enemy.14 Our men were driven from the Stockade and, by night, about one third of the town was in the hands of the enemy. The stockade and many buildings were burned.

During the whole action, a reserve force of the enemy 500 strong had stood holding their horses a short distance to the right of the ground upon which my party and our opposing party were practicing our feats of horsemanship. These reserves had paid so little attention to us that we began to have but little fear of them. When day-light began to fade, however, we were drawn out, nearer to them than usual by four rebels who really did almost let us run upon them, and whom we did, for once, try in earnest to catch or to kill. When we had thus been drawn out farther than on any previous occasion, the whole party came thundering out of a depression after us, crowding us more closely than ever before. To our dismay, the 500 reserves now mounted hastily and moved to cut off our retreat to town. With us, it was now a desperate race for life. We passed a few yards ahead of the intercepting party. I was in the rear. Sergt. McElhaney was next.15 As we passed close in front of the head of the intercepting column, their yells and their shots were so terrific that they frightened my horse. He shied from the road, sprang into a pile of stones, and fell throwing me over his head and hurting me quite severely. As he arose, I sprang upon him, threw my arms around his neck, and, with my face to his mane, let him dart into the thick cluster of hawthorns that fortunately lined that side of the road. Thus I escaped, with the enemy in 20 yards of me. When he saw me fall, Sergt. McElhaney reigned up his horse to save me or share my fate, but I instantly cried out: “Leave me! Save yourself!”

As usual, my men halted near the rifle pits at the edge of the town. They thought that I was lost. They were greatly delighted, therefore, when, a few minutes later, I came up bare-head and well-scratched by the thorns through which my brave old Hawk-Eye had carried me. The enemy had halted in line 200 yards away. Fearing that they would come in on a charge, I sent for reinforcements to be hurried to me at once. My messenger brought back word that not a man could be spared, and that I must hold my part of the town with my twenty men or all would be lost. Capt. Bob. Matthews, with 15 other wounded men from the hospital, came out to aid me.16 Even these poor heroic skeletons did me much good. Calling tauntingly to the enemy from our sheltered position, and sending some effective shots, we made them believe that we were quite strong and that we were eager for them to attack us. They withdrew. Dense darkness and an oppressive silence reigned around us. There had been a terrible struggle between the main bodies just as daylight was departing. Of the result of that struggle, we knew nothing. We cautiously moved toward the public square. It might be in possession of the enemy. At last we were met by a small party of men. It proved to be Burch and a few comrades of our own company. From them we learned the result of the battle as given above. We also learned that several members of our company had fallen—all like heroes. Burch afterward gave me the following account of his part of this battle:

Dear Captain:—At the Battle of Springfield, you were engaged, you know, in a different part of the field. At about three o’clock P.M. Marmaduke was forcing his way into Springfield down South Street. At that time, we were on the Buffalo Road at the end of Booneville Street. Being ordered up, we met the rebels 50 yards from the public square. Lieut. Col. Pound was in command of the battalion. Capt. Flagg was at the head of the column dog drunk. We were marched up to within 20 yards of the advance column of the rebels and ordered to fire. The battalion were marching by fours. The rebels opened a destructive fire upon the battalion, and this fire caused some disorder. I was in the rear. I saw the peril that we were in. I galloped up and said to Col. Pound: “Col. What are you going to do,” and he replied, “What had we better do?” I said “Dismount and charge.” He assented. I threw the men into line and ordered a charge, ordering the men to fire their revolvers. Just at that moment, the rebels had captured two pieces of artillery that had been brought from Fort No. 1. They now turned these pieces upon us. The men faltered a little. Soon, however, order prevailed, and we made the charge notwithstanding the artillery fire and the galling fire of small arms. Our boys raised the Indian war whoop and we drove the rebels back into the Stockade. On the right, our forces had been driven into Fort No. 1. When, however, they saw the rebels falling back, they sallied forth from the Fort, and again fiercely renewed the engagement on that side. As if with solid walls, we now held the rebels on every side. For an hour, I was exposed to a galling fire, I being the only mounted man on that line. (Having been severely wounded in the foot while a soldier in Texas, Burch was quite lame. Hence on nearly all occasions, to the great exposure of his life, he remained mounted.) My horse was shot in the head, and falling upon my left leg mashed it severely. I did not then know, however, that I was much hurt. As soon as I got loose from my horse, I went back, got my other horse, and returned to the front. You know Capt. how the other field officers acted. We held the rebels there till dark. Then, by Col. Pound’s order we mounted and moved to the left to feel of the enemy. They threw a shell very near us. Then Col. Pound had us fall back 200 yards and dismount. When I dismounted, I could not stand, my leg had swollen so much.17

When I reached the public square, I found our battalion drawn up there awaiting orders. A few hard tacks were issued to the men where they stood, and a little feed to the horses. Every few moments, a flash of light would be seen, a heavy shot would crash through the houses or scream through the air over our heads, and the thunders of a cannon would burst forth on the silence of night. What was the enemy doing? Gen. Brown having been wounded, Col. Crabb of Iowa, a brave and efficient officer, was now in command.18 I went to his office and found him trying to find out what the enemy was doing. The reports of his messengers were very unsatisfactory. At last, I told him that I could obtain for him the information he wanted. He said he wished that I would do so, and that he would have called upon me to do this only that he knew that I had had no sleep or rest for three days and two nights. He said he knew that I must now be nearly exhausted.

Leaving Col. Crabb’s office, I passed up South Street to Fort No. 4.19 Entering the fort a moment, I informed the officers that I was going out in front of their position to ascertain the movements of the enemy. I let them know this lest I might be shot by mistake from the fort. Leaving the fort, I passed out into the darkness on the Fayetteville road. When about a hundred yards from the fort, I got down and crept upon my hands and knees. I could hear the rebels coughing not far from me. They seemed to all have severe colds. The nearest coughing was in a blacksmith’s shop that stood at the forks of the Fayetteville and the Ozark roads.20 Creeping nearer, I learned that the coughing was done by guards stationed in the shop. Creeping around the shop at a little distance, I soon found myself upon the ground upon which the fiercest fighting had been done. I began to come upon dead men scattered about upon the ground. There was a flash of light and the thunder of cannon in front of me. The enemy was again firing upon the town. There was another flash and another burst of thunder, this time behind me. The fort was replying to the enemy’s fire,—replying with shells that passed uncomfortably near my back as they went screaming over me. I felt the wind that they made, and saw the burning fuse pass like a faint streak of lightning. Many shells thus passed over me from the fort, and several heavy shots in the opposite direction from the rebel batteries. Whenever I saw a flash of light, I flattened myself against the ground till the messenger of death passed over me. Then I crept to one side to get out of the line of these messengers.21

The firing soon ceased on both sides. The rebel batteries were moving. I heard a good deal of coughing near the smoldering ruins of several houses that had been burned. Creeping nearer, I found the beds of coals that remained of these houses surrounded by men sleeping upon the ground.22 Creeping around these sleepers without disturbing them, I crept farther out upon the battle ground. I found more dead men. Besides these, I found myself surrounded by several wounded men. Some of these were calling for help and for water. After calling awhile in vain, some of them would curse; others would pray. Some were delirious, talking, as they supposed, to their mothers and other dear ones in their far away homes. After awhile, some of these ceased to speak. A rattling in their throats ensued. Then all was still. And there they lay alone in the dark night stiffening upon the frozen ground of the battle-field. They never again saw the homes and the loved ones that they dreamed of as they were sinking to that “sleep that knows no waking.” I know not to which side they belonged. Probably to our side. The enemy would hardly have left their own wounded so long thus uncared for. Several of our men did fall on that part of the field. The dying men were probably, some of them at least, my own dear friends and comrades. At any rate, several of these were found next morning upon that ground, their bloodless upturned faces covered with frost. I did not dare approach any of these wounded men, though I lay still among them for an hour or more waiting to learn the meaning of an extensive conversation a little beyond. The enemy seemed to be organizing some movement which they wished to execute as secretly as possible. There were no bugle calls, no loud commands. The officers were rousing the sleeping men as quietly as possible and getting them into line. Those nearest our lines were not yet being disturbed. For some time, I could not make out what it all meant.23 At last, however, I discovered that the main body was moving out to the south-east, in the direction of Gov. John S. Phelp’s farm which lay over a mile from town.24

I now wished to creep out and return to Col. Crabb with my information. I saw, however, an ambulance approaching me surrounded by a small party of men carrying lanterns. I must lie still a little longer. They were gathering up the wounded. As they approached, some of the wounded men near me called to them. These men were placed in the ambulance. Placing my big shot-gun under me, I lay flat upon the ground with my face in the dirt. “Here’s a dead man,” was called out close upon my right. My heart flopped about violently. “And here’s another,” was spoken right at me, as a lantern was lowered to the side of my head, and a boot was pushed gently against my side. I think my flopping heart ceased to move at all. I did not breathe. “Well,” said an officer, “d—n it, don’t fool away your time with dead men, find the wounded!” They passed on. I was again alone in the darkness. I was growing a little nervous and determined to depart. By too long a stay among the dead, I might become a dead man sure enough.

Turning around, I cautiously crept back on the same route by which I had come. I felt an irresistible impulse, however, to hurry. Creeping seemed soon to become an intolerably slow and laborious mode of locomotion. I concluded to risk rising up and walking. I thought the darkness would hide me. I did arise and look around. I was about thirty yards from the black-smith shop, directly opposite the further corner. I was seen. “Halt!” came from the door, and three men stepped outside. I was already halted. I stood motionless. “Who goes there?,” was added. “A friend, I reckon, who are you?,” I replied. “You come up!” they answered, cocking their guns and bringing them to bear upon me. “Well, I will come up,” replied I, “but I wish to know whether you are Federals or southern soldiers.” By using the terms Federals and southern soldiers, I made them believe that I was a rebel, these terms being in common use among the rebels, but being rarely used among loyal men. They answered, “We are southern soldiers.” “Oh! then,” said I, “you are all right. I am a southern soldier myself and got lost from my command in the last hard struggle as it was getting dark.” “Well,” said they, “you are all right now. Come up!” By this time I had selected my course and had partially thrown them off their guard. I replied, “Boys, if I was sure you were southern soldiers I would not care, but—” At the word but, I darted past the end of the shop, thus placing a corner of the building between the guards and myself. A moment later, I was streaking it along the other side of a heavy boisdarc hedge. Not a shot was fired. I had escaped. But my night experiences on that battleground can never fade from my memory.

Having reached Col. Crabb’s office, I made my report. He complimented me very highly, and, at my request, gave me permission to do any “devilment” to the rebels that I might find it in my power to do them. I hoped that I might find it in my power to do them a good deal of this same “devilment.” I hoped to capture the guards in that blacksmith shop, without alarming any body else. Could I succeed in doing this, I could then lead a body of men secretly through the shop and into the enemy’s camp, and there could surprise his rear guard still sleeping around the beds of coals. In order to capture the guards without creating any alarm, I would dress myself and half a dozen men in citizen’s clothing, and approach the guards. When they challenged us, we would claim to be southern men coming in to join the army under Marmaduke. Since squads of such men were constantly coming in, we would be believed. The guards would call us in to keep us till they could turn us over to an officer. When thus called in, some of us would seize hold of the guns of the guards, while the rest of us would place cocked revolvers to their heads, threatening instant death if they made the slightest noise. Having thus captured the guards,—if I should succeed in this—, I could easily accomplish the balance of the undertaking. I still think the plan was a good one. It took us some time, however, to get ready. The result of the delay was that, when we reached the shop, the guards and all their living comrades were gone. The dead alone of both sides held possession of the battleground.

Having failed in this undertaking, I took half a dozen mounted men and went on a reconnoitering expedition. I found the enemy feeding upon Gov. Phelps’ farm. The men and the horses together were making a great deal of uproar. Leaving my men at a distance of 200 yards, I dismounted and crept on my hands and knees through the thicket of brush that lay on that side. I could hear horses making a noise not far from me on the other side of the thicket. I wanted a few of these horses. I also wanted a few men, especially officers. I was not destined, however, to obtain either horses or men. Morning was now dawning. What I was to do, I must do quickly. I crept on looking and listening. “Halt!” rang out some 30 yards to my right. Could I have been seen or heard? I kept perfectly still. “Who goes there?,” was added. “Officer of the day,” was replied. Then came, “Advance, Officer of the Day, and give the countersign!” “All right,” thought I, “Mr. Officer of the Day, I will try to compliment you with the contents of my big shot-gun.” Having relieved the guard, the officer, with about 30 mounted men, approached me, the men scattered out so, as they picked their way through the bush, that some would run right over me and others came between me and my men, thus cutting off my retreat. I was in a comparatively open space. I could not lie concealed. There was now too much light. I must now run for my life. I would let the Officer of the Day and his men alone, if they would only let me alone. I arose and fled. “Halt! halt!” resounded after me. I did not halt. Every time the word was repeated, I ran just a little faster. Again I had failed to distinguish myself by any remarkable feat of personal prowess.

Reaching my men, I sent two of them in to report to Col. Crabb the present status of the enemy’s affairs. With the balance, I remained to make further observations. The uproar increased. Every body seemed to be out of humor. “Some d——d thief has stolen my over-coat,” yelled one. “G-d d—n you, you never had any over-coat,” yelled another. “Fall in! G-d d—n you, fall in!” roared an officer. “Ho-ah! ho-ah! ho-ah!,” roared a mule. “Where’s that feller that claims this sorrel mare? I’ll be d——d if I’m going to take care of my own horse and every body else’s too,” yelled another. “Close order! forward! march!” roared another officer. “Ho-ah! ho-ah—ho-ah!” roared another mule. And so on in a thousand other cases. Fifteen minutes later, I sent back another report. It was now full day light. The rebel army was moving around to the east,—to our weakest point, the point at which they should have made their attack the day before. I dreaded this movement. We could not long resist an attack on this side if made in a charge. I sent my last man to warn Col. Crabb of the new danger that threatened us. I was glad that the Col. had command. He would hold out to the last. Gen. Brown, in my opinion, would have surrendered at discretion.

All alone now, I took a position on an eminence from which I could watch every movement of the enemy. I never saw a finer body of cavalry. The light of the morning sun, gleaming from their polished weapons, added to the brilliance of their appearance.25 Presently they halted, just where I feared and expected that they would, due east of the town.26 Here they formed in order of battle. Expecting them soon to come in on a charge, I now hastened back to town. Col. Crabbe had not been idle. Already he had the streets on that side strongly barricaded with steam boilers, heavy machinery, &c. He had perforated the brick buildings with port holes, and, at each port hole, had placed a sick man or a wounded man, propped up with a pile of flour sacks. He had done every thing that could be done to prepare for a desperate defence. “Victory or death” was the motto.27

We feared the attack. We prepared for it. We waited for it. We ceased to fear it. We grew eager for it to begin. What was the enemy doing? Presently a flag of truce arrived with an order for us to surrender. Again Marmaduke had committed a serious error. He should have charged at once. We returned a message with the flag of truce, asking Marmaduke what he meant by the word, “surrender.” We informed him that the word was not to be found in our books, and that until we knew the meaning of the word, we could not say whether we would or would not surrender. Our ignorance of the meaning of the word so disgusted him that, without any further ceremony, he marched away in a south-easterly direction.28 We could hardly believe our eyes when we saw him leaving. We did not expect so easy a victory over such a force.

When he had been gone some two or three hours, we discovered through our field glasses, from the top of the Court House, a body of men on a hill several miles to the north of the town. Who could these be? With a party of 50 men, I went out to ascertain. Coming upon them by surprise, I bawled out:—“Fire one gun and you all die! Down with your arms!” The poor fellows were frightened out of their wits. They had no arms to “down with.” They were the sorriest lot of men I ever saw. Not one of them could have borne arms. Some were very old, some were blind, some were deaf, some had an arm gone, some a leg,—something was wrong with every one of them, and there were about forty in all. Through curiosity, they had assembled on that hill to ascertain, if possible, which army held the town.

On my return, I found the men still waiting ready for battle, and growing braver every moment as the prospect of a battle became more doubtful. Presently an old man came in with four fine horses and asked for Marmaduke. He said he wanted to sell these horses for fear the Federals might take them. He said that he had taken the oath of loyalty to the United States, but that the oath was only from the teeth out. Seeing the mistake under which he was laboring, I told him that Marmaduke was too busy to see him, but that I could attend to his business as well as Marmaduke could. I told him that he had brought me exactly the number of horses I was wanting. I had a Sergt. take charge of the horses. “Of course, you will give me a receipt for them?,” said the old sinner, beginning to look a little uneasy. “Oh! no,” said I, “You will not need any receipt.” “But how will I get my pay?[”] queried he. “You will not get it at all,” said I, “can you not give that much for the good of the cause?” “I expected pay,” said he. “I have expected many a thing that I did not get,” said I. “You will get no pay, and besides this, you will have to help us fight.” He looked frightened,—looked as if his zeal for the rebel cause had about oozed out. “I do not want to fight,” said he, “and I have no gun.” “Of course you do want to fight,” said I, “it is only your modesty that makes you say that you do not; and, as for a gun, I will furnish you one; and will also place a man behind you to shoot you dead, if you do not perform your full duty in battle. In violation of your oath, you came in here to help our enemies. Now you shall help us or die. You do not deserve the treatment of a prisoner of war, and you will not receive it. We are Federals; I am Kelso; now you know what to expect.”

Soon after the occurrence of this little episode, a long train of wagons of every description, about a hundred in all, came driving in from the south. These were driven by rebels, most of them old men, women, and boys, who came, they said, to haul off the sugar, the Lincoln coffee, the flour, and the other provisions that Marmaduke had assured them would be taken in quantities far greater than his army could use or carry away. We thanked them kindly for bringing us just the number of wagons and teams that we wanted.29 Putting the few able-bodied men to work on our fortifications, we sent the other poor would-be plunderers back on foot, without any of the good things for which they had come.

Toward evening, finding that Marmaduke was really gone, our courageousness became truly wonderful. We felt that we could whip the devil himself, if he would only venture to show himself. We would pursue Marmaduke. Three hundred of us would chase six thousand rebels. Just think of it.30 We did thus chase them. We kept a long way off, of course, so that they should not know that we were after them. But we were chasing them all the same. Lieut. Col. Pound went in command; Capt. Flagg was second, and I was third.31

After a march of two or three hours, Col. Pound and Capt. Flagg became disgustingly drunk;—too drunk to keep their saddles. They were rolled into an ambulance and hauled along like a couple of dead hogs. I had charge of the look-outs and the advance guard. Presently I found that the command had halted and were in confusion. I stopped and waited. After awhile, I heard some one calling my name. I answered, and a subaltern officer rode up and informed me that the men were in a state of mutiny, refusing to advance nearer the enemy under the command of a couple of officers, gibbering, slobbering, and idiotic from beastly drunkenness. I ordered him back to inform the men that I had charge of the look-outs, and that just so soon as any real danger threatened us, I would put Col. Pound and Capt. Flagg under arrest and take full command myself. When the men heard this, they cheered loudly, and were willing to follow wherever I would lead. About midnight, Col. Pound ordered a halt at a farm house, and, without instructing the men what to do, he and Flagg and a subaltern or two went in and slept the sweet sleep of the drunkard. We could see the light of Marmaduke’s camp-fires. Every thing depended upon me. I kept wide awake on the look-out. Most of the men managed to sleep with their bridle reins in their arms. The weary horses were glad to stand still and sleep. Next morning, weary and disgusted, we returned to Springfield.

For four days and four nights, I had no sleep and no rest. I had almost reached that point where it becomes a physical impossibility to endure more. But I was not still to rest. I do not now remember how it came about,—my mind was becoming so sadly confused—but I was ordered, or, more likely, I volunteered to go out in command of a party of 25 men to meet and to guard a train that was on its way to Springfield from Cassville. We marched out some twenty miles or more. The sun shone out clear and warmed the air. The men slept soundly in their saddles. I could not trust one of them to stay awake and keep a look-out. I must keep awake myself. The horses, reeling and stumbling, slept as they walked. Hot water from my burning eyes constantly streamed down my cheeks. My sight was failing. My mind was failing. I tried to think what we had been doing for the last hundred hours or more. I had to give up the attempt. All things were in confusion. I could not unravel them. I tried to think where we were. I could not even make this out. Finally I thought that, maybe, I was simply dreaming a distressful dream. I pinched myself to wake myself. My flesh felt numb. I did not awake. At last I gave up all thoughts but two: “look out for the enemy; look out for the train!” To these thoughts, I would still cling. I constantly changed my position from side to side in my saddle. Still an irresistible sleepiness would come over me. I would then spring to the ground and lead my horse. Oh! how weary my legs were! How weary my whole body,—my whole being was! I would go to sleep while walking. I would dream that I heard the firing of guns. I would start to fall, and this start would rouse me. I would clamber back into my saddle, and go through the same routine. Of the intensity of my suffering, I need not speak. Language could not express it. Those who have ever suffered as I then did, know what I mean. Those who have never thus suffered could not possibly be made to understand my meaning.

About sun-set, we met a small party of Federal soldiers who informed us that the train we were seeking had returned to Cassville, and was already safe. For a few moments, the excitement of meeting these soldiers aroused us from the almost death-like lethargy that was upon us. But what should we now do? Without rest, neither horses nor men were able to return to Springfield, and not a man of the party was able to stand guard. I did not hesitate. I led my men a mile from the road and concealed them, one in a place, fifty yards apart, in a dense and extensive hazel thicket. Scattered thus, the enemy could not, in the darkness of night, find them while they slept. Going about fifty yards beyond my last man, I hitched my horse and, tumbling down, was soon fast asleep on the frozen ground. I did not wake till day-light. When I opened my eyes, all around me was white with frost. Never had sleep been sweeter or more refreshing. I hunted up my men. They were all still asleep. I found them by means of the noise made by their horses breaking and eating brush. Some of my men were beardless boys and, as they lay there still before me in the frost on the frozen ground, their faces looked so blue that I almost feared they were dead. When roused, they all declared that they had never slept better. By two o’clock P.M., we were in Springfield.32 On the next day, with a small party of men, I visited Ozark. I found that my family had been pretty well robbed of blankets and such things, but that, otherwise, they had not been ill treated.

For some weeks, we lay at Springfield, making frequent scouts of three or four days each into the counties south and east of that place. On all these scouts, there was more or less of excitement. A few prisoners, horses, guns, &c. were captured. No fighting, however, was done on any of them. If I remember correctly, I was present on all of them. On one occasion, when I was third in command, the weather was very severe. Every night, all the other officers slept in houses. As usual, I remained out with my men, bearing all their hardships and privations, and cheering them with my words of praise and encouragement. Because I would thus remain out, I was made officer of the guard every night. On the last night out, a heavy snowstorm was upon us. We stopped at the farm of a wealthy old rebel. The men were hungry and were out of rations. The horses were in almost a starving condition. Here was an abundance of everything needful for both men and horses. I congratulated the men on our good fortune. As usual on such occasions, the officers were all invited in to enjoy a blazing fire, a bountiful repast, and warm, soft beds. All but myself accepted the invitation. Soon I received the usual order appointing me officer of the guard. In addition to this usual order, I was also ordered to forbid the men to take any corn, oats, or hay for their horses, or to kill any pigs, sheep, turkeys, chickens, &c. for themselves. I was indignant. What were the men and horses to do? We were also forbidden to burn any rails, and we had nothing else for fuel. Without food or fire, the men would suffer severely. I called them together. I read them the order. Their faces grew dark, and deep, low curses were muttered among them. They asked me what they should do. I told them to make fires of split timber, to feed their horses on dried vegetables of any kind, and to eat such pigs, turkeys, chickens, &c. as happened to fall and break their own d——d necks or happened to be kicked and killed by the horses. Of course I was evading the villainous order I had received. The men took the hint. The horses soon had an abundance of good feed, great fires were soon blazing, and the air was freighted with the “sweet smelling savor” of roasting turkeys, chickens, &c. Besides all this, I found the men well supplied with apples and honey. They were in high good humor, and I had to eat a little with every mess in the entire encampment.

About the close of January, I think it was, we marched to Forsythe.33 Here we remained a couple of weeks, seeing our horses die of starvation. We then marched to Linden, 15 miles south east of Springfield. Here we remained till the breaking up of winter. Our horses continued to die for want of forage. We then returned to Springfield where we remained, I think till the early part of May. While lying here, our regiment was broken up and incorporated with the 8 Reg. M. S. M. Cavalry, commanded then by Col. J. W. McClurg, but soon afterward by Col. J. J. Gravelly. My company became Co. M. of this regiment. Soon after this consolidation, my company and Capt. Breeden’s—soon afterwards commanded by Capt Ozias Ruark—were ordered to Neosho to operate against the various bands of bush-whackers that infested that part of the country.34

While at Springfield, I bought a pretty little house for a residence, and moved my family into it. They would now be among friends and be comfortable. My only trouble was Dr. Hovey. Leaving his family in Buffalo, he was soon in Springfield, pretending that he could do better in his profession there than he could in Buffalo. His real object, however, I then feared and as I now almost know, was to be near his too willing victim, my beautiful and beloved wife. I could hear of his being a great deal at my house, some scandal being created by the frequency and the time of his visits. My children, too, were loud in his praise because he sometimes gave them money of evenings to attends shows and concerts in the town. Thus he had all to himself the idol of my heart, the angel of my dreams. This he had with her own connivance. She was only too willing. While I was braving death for my country in a thousand forms, while I lay upon the cold ground thinking or dreaming of her, while the rain poured down upon me in the dreary night, my darling Susie, according to her own voluntary confessions afterwards made, was suffering this smooth-tongued serpent to pour into her charmed ear the tale of his illicit love, to fold her to his bosom, and to cover her lips with his hot amorous kisses. Will those who have loved, who have trusted, and who have been betrayed, blame me for writing bitterly about these things?35

Source: Kelso, “Auto-Biography,” chap. 20, 790–800.

1. “Report of Capt. Milton Burch, Fourteenth Missouri State Militia Cavalry, of Skirmish at Fort Lawrence, Beaver Station, Mo.,” Jan. 16, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 193: “I started from Ozark on the morning of the 4th of January with 100 men.”

2. Ingenthron, Borderland Rebellion, 258: “The Beaver Station post protected a water-powered mill built by William Lawrence prior to the war. In the winter of 1862–63, the mill was employed in grinding breadstuff for the Union army and the people living in the surrounding countryside. Usually the military installation was manned by about 100 militiamen from Douglas and Taney Counties, and also served as a base for scouting expeditions and guerilla activities. The fort was a two-story brick building, 150 feet long and 40 feet wide, constructed of logs 12 inches thick, dovetailed and closely fitted. The second story projected outward over the first story. Portholes for musketry lined the walls around the entire building and were mortised on the inside to enable turning muskets to almost any direction. Eight or ten log buildings adjacent to the fort were used as barracks.”

3. The Union Army believed that the Confederate forces led by Brig. Gen. John S. Marmaduke did have as many as 6,000 troops, but actually the number was about 2,300, and he planned to rendezvous with a separate column of 850 under the command of Col. Joseph C. Porter. On Marmaduke’s 1863 expedition into Missouri and the Battle of Springfield, see the dispatches and official reports of the Union and Confederate officers involved in OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 178–211; “The Battle of Springfield, Mo.,” New York Times, Jan. 26, 1863, by a reporter signing as “Kickapoo” who was at Fort No. 4 during the attack; John N. Edwards, Shelby and His Men; or, The War in the West (Cincinnati: Miami Printing, 1867), chaps. 8–9, by a Confederate major who was Col. Joseph Shelby’s adjutant; and Holcombe, History of Greene County, 424–56, an excellent local history informed by interviews with some of the participants. See also Robinett, “Marmaduke’s Expedition”; Ingenthron, Borderland Rebellion, chap. 25; Goman, Up from Arkansas; and Wood, Civil War Springfield, chaps. 10–11.

4. The Beaver Station commander was Maj. William Turner of the 73rd Enrolled Missouri Militia. Burch’s report, Jan. 16, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 194: “I immediately [upon detecting Marmaduke] dispatched a messenger back to the Beaver Station, with instructions to dispatch forthwith to Ozark. … I arrived at Beaver Station at 4 o’clock in the morning of the 6th. I then asked the major if he was in a condition to fall back; he replied that he had no transportation.” Holcombe, History of Greene County, 437: “Turner was an old man who had been long in the service, and had heard a great deal more of the Confederates than he had ever seen of them, and was incredulous about there being any more of them in the country than a squad of bushwhackers.”

5. Beaver Station was attacked by 270 Confederate cavalry under the command of Col. Emmett MacDonald. Robinett, “Marmaduke’s Expedition,” 157: “The Confederates rushed the fort. Surprised, the Federal garrison fled leaving some 100 horses, five wagons, and 300 stands of arms. The fort and all supplies that could not be carried away were burned. The arms were buried.” Ingenthron, Borderland Rebellion, 260: “Major Turner, the Union commander, was wounded in the attack, and some half dozen Federal soldiers were killed.”

6. Holcombe, History of Greene County, 430: “Springfield was now the great military depot for the Federal ‘Army of the Frontier.’ … There were forts and cannon and muskets and powder and shot and shells and provisions and quartermaster’s stores in great abundance,—but few soldiers. Nearly all the available troops had gone to the front.” Gen. Egbert B. Brown, Enrolled Missouri Militia commander of the Southwest District, counted 453 men of the 3rd MSM Cavalry, 289 from the 4th MSM Cavalry, and 378 from the 18th Iowa Infantry. Kelso’s 14th Cavalry, under Lt. Col. John Pound, would arrive with 223. An urgent call would go out to militia men in the surrounding counties, and a few hundred would arrive through the night of Jan. 7–8. A few hundred convalescents who had been recently discharged from medical care were in town or camp, and some of the sick or wounded men still in the buildings and tents serving as hospitals had to be well enough to prop themselves up and fire a gun. Civilian men and older boys willing to fight were issued arms. Altogether Brown estimated that he had a fighting force of about 2,000 men (General Brown’s reports to Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, Jan. 8, 1863, 10:00 a.m. and 11:50 p.m., OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 179–81). The 250 men from the Enrolled Missouri Militia would raise the total to over 2,300 (Goman, Up from Arkansas, 123n26).

7. Burch’s report, Jan. 16, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 194: “I started for Ozark, leaving the main road and taking a right-hand road. Hearing that a portion of the enemy had gone up Little Beaver with the intention of cutting us off from Ozark, I travelled slowly, using precaution against surprise, and arrived at Ozark about 10 o’clock of the night of the 6th. I then ordered all the baggage to be conveyed across the river on the road to Springfield, which was promptly complied with, and waited for further orders, which orders I received for us to fall back to Springfield.”

8. Five forts and earthworks had been planned, but only two of the forts were finished and usable and only Fort No. 1 had any artillery (two brass cannons that fired six pound shells); see “The Battle of Springfield, Mo.” On the artillery, see General Brown’s dispatch, Jan. 8 [1863], 10:00 a.m., OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 179–80: “I have our iron 6 and 12 pounder guns and howitzers, which I mounted last night, in addition to two brass 6-pounders at Fort No. 1.” The iron cannon, as Wood describes in Civil War Springfield, 100, were “old guns … which were lying virtually abandoned on the grounds of the Calvary Presbyterian Church,” and “were mounted on wagon wheels as temporary carriages, taken to the blacksmith shop for repair, and then rolled to Fort No. 4 and placed in position.” Brown also reported that “the convalescents in hospitals, employees of quartermaster, commissary, and ordinance, and citizens of all ages are being armed. … The brick buildings are being pierced for musketry” (180). The New York Times reporter thought that the general feeling among the soldiers was, “We may hold the town, and we will not give it up without a fight; but we shall probably be whipped.”

9. “The Battle of Springfield, Mo.”: “The city thus fortified lies half in the prairie and half in the timber. Upon the north and east all is forest; upon the south and west the country is entirely open. The rebels chose to make their attack from the south, which was an error, for two reasons. First, because they were more exposed to our view, in their advance from the south, than they would have been from the east; secondly, because the north and east side of the town were not defended by forts.” See also Holcombe, History of Greene County, 438–39. General Marmaduke had hoped to be joined by Colonel Porter’s brigade, but in his reports he did not mention Porter’s absence as the explanation for his battlefield tactics or his ultimate retreat (OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 194–98), though he may have done so later.

10. “The Battle of Springfield, Mo.”: “Without one word of notice to remove the women and children, they opened fire upon the town, with solid shot, though they knew that scores of their own friends, both women and prisoners, were exposed to the same danger as our loyal citizens. … ‘Gentlemen,’ said Gen. Brown, who stood on the southwest bastion of Fort No. 4, ‘this is unprecedented; it is barbarous!’” See also Holcombe, History of Greene County, 440: “It is not certain that Hoffman [the Union gunner at Fort No. 4] did not open the fight, by shelling Marmaduke’s advance,” but both Brown and the New York Times reporter were right with Hoffman at the fort and would have known. There were no official reports of injuries of women and children, although the Times article did note that one shell “exploded in a room where there were four women and two children lying upon the floor, covered with feather-beds.”

11. “Report of Brig. Gen. Colly B. Holland, Missouri Militia, of Engagement at Springfield, Mo.,” Jan. 11, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 182, describes the deployment of Union troops. Facing the enemy in the south, “General Brown formed his line of battle, with detachments of cavalry [including nearly all of Kelso’s brigade] on the left, southeast of town, a detachment of the Eighteenth Iowa on their right.” Fort No. 4, with two mounted guns, was in the center, with the 74th Enrolled Missouri Militia and the convalescent soldiers, dubbed the “Quinine Brigade” after their bitter fever medicine. About 250 yards further forward and to the right (west) there was an empty two-story brick college building, surrounded on three sides by a palisade, and a bit beyond that a regiment of 72nd Enrolled Missouri Militia with a few detachments of cavalry flanked further on the right. “Fort No. 1 about one-half mile to the rear, being the extreme right, … was garrisoned by the Eighteenth Iowa and citizens.”

12. Holcombe, History of Greene County, 442: “At about 2 in the afternoon the Confederates, dismounted, began moving around toward the southwest part of town. … The Confederates advanced from the south towards the north and northwest, coming up the little valley at the foot of South and Campbell streets, and sweeping over the ground to the westward. On they came, through ‘Dutchtown,’ as a collection of houses at the foot of Campbell street was called, taking the houses and their outbuildings for shelter as they advanced—forward to the stockade college building, which had been left unguarded, and captured it without losing a man.” “Report of Col. Benjamin Crabb, Nineteenth Iowa Infantry, of Engagement at Springfield, Mo.,” Jan. 10, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 185: By 3:00, the Confederates “were making strong efforts to turn our right, and, after being driven from our center, threw their main force forward for that purpose, when they were met by” the 72nd Enrolled Missouri Militia, the “Quinine Brigade,” the 3rd and 4th MSM Cavalry, five companies of the 18th Iowa, and the 2nd Battalion 14th MSM Cavalry (Kelso’s battalion, excluding his twenty men).

13. “The Battle of Springfield, Mo.” described the cavalry charges: “My blood quickened its flow, as I watched our brave boys gallop forward to the charge, then saw the enemy galloping in a long line to meet them, and heard the sharp, rapid firing of carbines, on both sides. After each charge and fire both sides would turn and gallop back, with small loss on either side.”

14. A detachment from the 18th Iowa led by Capts. John A. Landis, William R. Blue, and Joseph Van Meter came down from Fort No. 1 to help fend off the attack with a fieldpiece—one of the brass six-pounders—but they wound up beyond the federal line and exposed to the enemy. Twenty Confederates led by Maj. John Bowman dashed forward to capture the gun. All the Federals’ horses pulling the gun were shot down. Holcombe, History of Greene County, 444: “In the fierce fighting that followed Captains Blue and Van Meter were mortally wounded, two or three of their men were killed, and Capt. Landis and a dozen more Hawkeyes were severely wounded, while the Confederates lost Capt. Titsworth, Lieut. Buffington, and Lieut. McCoy, and four or five men killed, and perhaps twenty … wounded.” (Holcombe notes that “the particulars of the fight for the gun have been obtained from actual participants on both sides.”)

15. Sgt. Robert McElhaney, Co. H, 14th Regt., MSM Cavalry (NPS Soldiers’ Database).

16. Capt. Robert P. Matthews, Co. D, 8th Regt., Missouri Cavalry (NPS Soldiers’ Database).

17. Colonel Crabb’s report, Jan. 10, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 186, gave a dimmer view of the 14th’s performance: “At this critical time, an officer commanding a company in the Second Battalion Fourteenth Missouri State Militia, ordered his men to horse (as I was afterward informed), and the whole battalion came running in great confusion to the rear and took to horse. I tried in vain to rally them; they seemed panic-stricken. This caused a partial giving way among the other troops. I had no difficulty in rallying them, and they went again into the fight. It was now near dark, and the enemy an additional demonstration on our left. By this time, Lieutenant Colonel Pound, commanding, had succeeded in reforming the Second Battalion Fourteenth Missouri State Militia. I ordered him to advance on the enemy’s right, which order he promptly executed. The enemy fired but a few rounds, and again retired, leaving us in full possession of this part of the field.”

18. Wood, Civil War Springfield, 110–11: “As the fighting shifted westward, General Brown rode forward along South Street with his body guard to near the corner of State to oversee the battle and encourage his men. While there, consulting with some of his officers, he was shot from his horse by a Rebel sharpshooter concealed in a house or other nearby hiding place. Brown was taken to the rear with a severely wounded arm, the bone having been broken above the left elbow, and he officially turned over command of the Union troops engaged in the battle to Colonel Crabb.” On the Confederate side, Major Edwards admired Brown’s courage: “General Brown made a splendid fight for his town, and exhibited conspicuous courage and ability. … He rode [the] entire length [of Confederate Col. Joseph Shelby’s brigade] under a severe fire, clad in bold regimentals, elegantly mounted and ahead of all so that the fire might be concentrated upon him. It was reckless bravado, and General Brown gained by one bold dash the admiration and respect of Shelby’s soldiers” (Edwards, Shelby and His Men, 139). The New York Times reporter wrote in his Jan. 26, 1863, article “The Battle of Springfield, Mo.” that “too much praise cannot be awarded Gen. Brown. … He has been much overlooked by higher authorities, much maligned by some of those under him, and even accused of cowardice. But his men now regard him with universal confidence and affection.”

19. Fort No. 4 was a square about 160 feet long and wide with gun emplacements on its southeast and northwest corners (Goman, Up from Arkansas, 27, 40).

20. Holcombe, History of Greene County, 445–46: “The lines of the two forces after nightfall seem to have been as follows: The Confederates were in two wings, which formed a very obtuse angle or letter V with the arms much extended. The point of this angle rested on the stockade [college], and the right arm (or the Confederate left), extended in a southwesterly direction along the Fayetteville road. The left arm (the Confederate right), ran in a southeasterly course across State street, through ‘Dutchtown,’ and past a blacksmith shop, out into the open prairie.”

21. “Report of Col. Joseph O. Shelby, Missouri Cavalry (Confederate),” Jan. 31, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 201: “When all was quiet, [Confederate Lt. Richard A.] Collins, with his iron 6-pounder and a small support, made a promenade upon the principal streets of the city. … This little party, whenever a light appeared, fired at it, and it served not only to encourage our tired soldiers, but it told to the foe, with thunder tones, that we were still victors, proud and defiant.” Col. Henry Sheppard, 72nd Enrolled Missouri Militia (Union), in Holcombe, History of Greene County, 449: “In the night I had the howitzer in the fort, a 12-pounder, pepper the rascals in the palisade college building, 250 yards away. The moon shown beautifully and the Dutch lieutenant (Lieut. Hoffman) made splendid practice. The secesh vacated it and at 1 a. m. I put a company in it.”

22. Shelby’s report, Jan. 31, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 201: “I drew my brigade off calmly and cautiously, formed them in and around the heavy stockade, and prepared to pass the night as best I could, although it was very cold, and the men had no fires, save the smouldering of consumed houses, burned by the terrified enemy at our first approach.”

23. Shelby’s report, Jan. 31, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 201: “The men lay on their arms until about 2 o’clock in the morning, when I deemed it best, as they were suffering greatly from cold and hunger, to withdraw, which was done quietly and in order, some of Colonel [Emmett] MacDonald’s command and Major [Ben] Elliot’s scouts picketing my flanks and front.”

24. Edwards, Shelby and His Men, 139: “About midnight Shelby’s brigade withdrew by regiments from the gloomy and fire-scarred town, and marched like silent specters across the cold gray prairie to their horses in the woods beyond, leaving behind a strong line of mounted skirmishers to remain until daylight. On their way back the hungry soldiers tarried long enough to visit the Hon. John S. Phelps’ splendid mansion, now silent and deserted: but unlike their enemies on ten thousand other occasions, they simply took the necessary articles for food and raiment. The mellow and delicious apples, the rusty bottles hid away many feet down under the earth, the flour, bacon, beef, blankets, quilts, and shirts were all taken—but nothing more.” Phelps was a Democrat and a Unionist. According to Michael B. Dougan, “Phelps, John Smith,” ANB, “The Civil War crippled Phelps financially. His farm was looted first by Union troops, who thought the presence of slaves made him a secessionist, then the Confederates burned his buildings.” See also “John S. Phelps Papers,” http://www.ozarkscivilwar.org/archives/3549.

25. Perhaps if Kelso had been closer, the sight would have appeared less impressive. General Marmaduke, in his report of Feb. 1, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 197–98, commented on his men being “indifferently armed and equipped, thinly clad, many without shoes and horses … without baggage wagons or cooking utensils.” Colonel Shelby’s report, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 204, remarked on their “unshod and miserable horses.” Major Edwards, in Shelby and His Men, 134, remembered that for the shivering Confederate soldiers on that expedition, overcoats were “an article more desirable than purple and fine linen.”

26. Col. Henry Sheppard, 72nd Enrolled Missouri Militia (Union), in Holcombe, History of Greene County, 449: “An hour later [after daybreak], with Gen. Brown’s field-glass, I sat in the bastion [of Fort No. 4] and saw the long lines of the enemy working their way eastward from the ‘goose pond,’ where they had withdrawn during the night. To only one idea did it seem reasonable to attribute this movement—that the attack was to be renewed from the east and north.”

27. Colonel Crabb’s report, Jan. 10, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 186: “On the morning of the 9th, they appeared in full force to the east, and about 1 mile from town. Preparations were made to receive them. A cavalry force was sent forward to engage them and check their advance; but they declined another engagement and retired in haste.” General Marmaduke’s report, Feb. 1, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 197: “A little after sunrise the column moved eastward on the Rolla road.” Colonel Shelby’s report, Jan. 31, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 203: “After the men had breakfasted the next morning, after ammunition had been distributed, and a leisurely forming of the brigade had been effected, we started from the scene of a hard fought battle … and we, after making a circuit of the town with floating banners and waving pennons, left it alone in its glory, because all had been done that could be done. Friday, the ninth, moved east with my brigade on the Rolla road.” Confederate 2nd Lt. Salem Holland Ford (1835–1915), Co. F, 12th Regt., Missouri Cavalry, thought, like his commanders, that the battle was a success, if not quite a victory, especially considering, as he remembered it years later, “the enemy had more than five to our one and had twenty pieces of artillery.” The Confederates, he wrote in 1909, “piled [the Union] dead very deep all about the outer defense” (Salem Holland Ford, Civil War reminiscence [photocopy], March 8, 1909, B 194, 20, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis).

28. General Marmaduke’s report, Feb. 1, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 197: “I addressed a letter, under a flag of truce, to General Brown, commanding at Springfield, stating that my wounded were left in charge of competent surgeons and attendants, and asking from him a proper treatment of all.”

29. Col. Crabb’s report, Jan. 10, 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 187: The enemy “came with the full expectation of easy conquest. They had invited their friends in the country to come and bring their wagons, promising all the booty they could carry; but, thanks to a kind Providence, brave hearts, and strong arms, they were most signally defeated in their designs of plunder.”

30. “The Battle of Springfield, Mo.”: “On Friday morning, the current of feeling in our midst had changed. Our troops were confident and exultant. They awaited the renewal of the attack, not only with equanimity, but with eagerness. We were, however, disappointed. The battle was not renewed, although a small party of the rebel cavalry made a feint at the eastern side of town, to amuse us and cover the retreat of the main body.”

31. Holcombe, History of Greene County, 447: “Col. Crabb decided to let well enough alone, and not attempt to follow Marmaduke and Shelby, who were moving out on the wire road toward Marshfield. A renewal of the attack was feared by some, as the prisoners had learned and reported the presence of Porter’s column, somewhere to the eastward. The cavalry was ready to advance if the order should be given, but no orders came, and only a reconnaissance a mile or so eastward and south was made.”

32. Sunday, Jan. 11, at 2:00 p.m., was also the start of Springfield’s funeral for the Union dead. The band and two companies of infantry marching as an escort, the bodies of the Union soldiers in wagons, their horses with their empty saddles, then the rest of the infantry, cavalry, officers, and citizens, moved slowly from Fort No. 4 back to the town square and then out North Street. Meanwhile, Marmaduke’s forces, marching east, finally met up with and joined Porter’s brigade. As Springfield buried its dead, fifty miles away the combined Confederate command battled a force of 880 Union men under the command of Col. Samuel Merrill at Hartville. Merrill’s troops, with their sharp-shooting artillery, inflicted heavy damage on Marmaduke’s much larger force until the Federals ran low on ammunition and had to retreat. The Confederates then marched through mountainous terrain in a snowstorm back to Arkansas. General Curtis praised his Union troops as heroes and reported to Missouri governor Hamilton Gamble on Jan. 12, 1863, that from Marmaduke’s expedition, “the enemy got nothing but a good thrashing and one gun” (OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 179). The Confederates, however, pronounced the expedition a success. They had destroyed forts and captured provisions, and they wrongly believed that they had forced federal troops planning an attack on Arkansas to fall back to Missouri. Marmaduke reported, too, that the raid had revived the spirits of Confederate sympathizers in Missouri (OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 1, 198).

33. On Jan. 21 or 22, Kelso and other members of the 14th were back at Ozark. Capt. Samuel Flagg ordered Kelso to march Co. H to Forsyth, thirty miles to the south. The subsequent exchange between the two men prompted Flagg to file charges against the lieutenant, and seven weeks later, on March 11, 1863, Kelso found himself facing a court martial at Springfield. Kelso was charged with “conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline.” Flagg’s complaint held that Kelso, in front of the men, absolutely refused to obey the captain’s order to march the troops to Forsyth. The lieutenant then said, according to Flagg, that he would not “move his company on any wild goose chase” and would not march until he saw the written orders that Flagg had received. Witnesses confirmed that Kelso had asked to see Flagg’s orders, complained of a wild goose chase, and also that he said “he had been obeying drunken officers as long as he was willing.” Kelso argued that improper orders and intoxicated officers had been a problem, and that he had also been provoked by Flagg’s abusive language. The court found Kelso not guilty. John R. Kelso Court Martial Case File, Springfield, Mo., Jan. 21, 1863, NN-2499, Record Group 153, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Army), National Archives.

34. On the reorganization of the MSM, see U.S. Pension and Record Office, Organization and Status of Missouri Troops, 21–47; however, the (incomplete) reproduction of General Orders No. 5 of Feb. 2, 1863 (see pp. 30–31), excludes the part about the reorganization of the 14th—instead, see OR, ser. 1, vol. 22, part 2, 97–98, and Annual Report of the Adjutant General of Missouri, 195. Flagg transferred to the 4th Regt., MSM, Feb. 4, 1863, and resigned from the military on Aug. 4, 1863 (“Soldiers’ Records,” MDH). Capt. Ozias Ruark had first served as a sergeant in the Cass County Home Guard and then as a private and second sergeant in the 14th MSM Cavalry. Col. Joseph W. McClurg had previously held the same rank in the Osage County Regiment of the Missouri Home Guard. In the 8th Regt., MSM Calvary, Colonel Gravelly had been promoted from second lieutenant (NPS Soldiers’ Database).

35. John and Susie Kelso had two more children together: Augustus (1865–70) and John (1867–1935). They separated in 1871, and John, Sr., moved to California. Their final divorce decree was rendered on Jan. 30, 1874 (“Abstract of Divorce Records”).