Five

THE MODERN CLEVELAND POLICE DEPARTMENT

The period of time between the early 1950s and early 1960s were among the most tranquil in the political history of Cleveland. Nevertheless, the police department continued to advance by developing new strategies to improve traffic safety and fight crime.

The death of Chief George Matowitz, the 13th chief in the department’s history, represented the end of an era. Matowitz was one of a handful of survivors of the capable young men brought into the department during the reforms of Chief Fred Kohler at the turn of the 20th century. He would be the last chief of police to serve under civil service. Since his death in 1951, 25 others have served as chief, some for a matter of days.

During this time, the face of the city itself was changing as a result of urban renewal and construction of the interstate highway system. Long familiar neighborhoods vanished, and many of those that remained became unrecognizable.

Rioting broke out in the city’s Hough neighborhood for six days in 1966, and for the first time since the violent labor strikes of the 1930s, the National Guard had to be called to maintain order. As bad as this situation was, it was only a prelude to the most tragic day in the department’s history.

On the evening of July 23, 1968, the Glenville neighborhood exploded with violence. Police officers from every part of the city responded, and by night’s end, three police officers had been killed and another would suffer, paralyzed, for 25 years before dying in 1993. Fourteen other police officers were injured, including 11 who had been shot. The rioting continued until the police and National Guard were able to restore order on July 28.

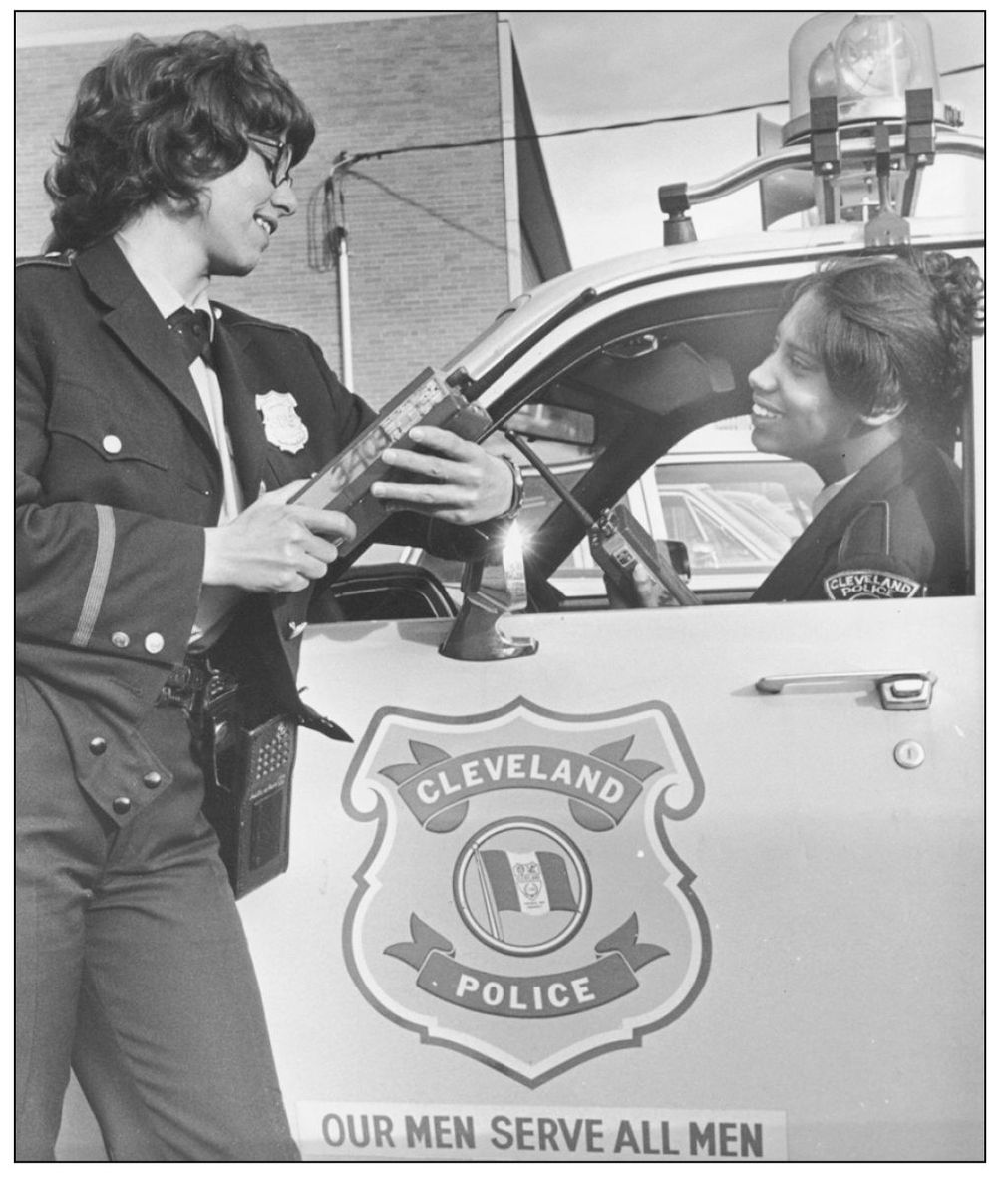

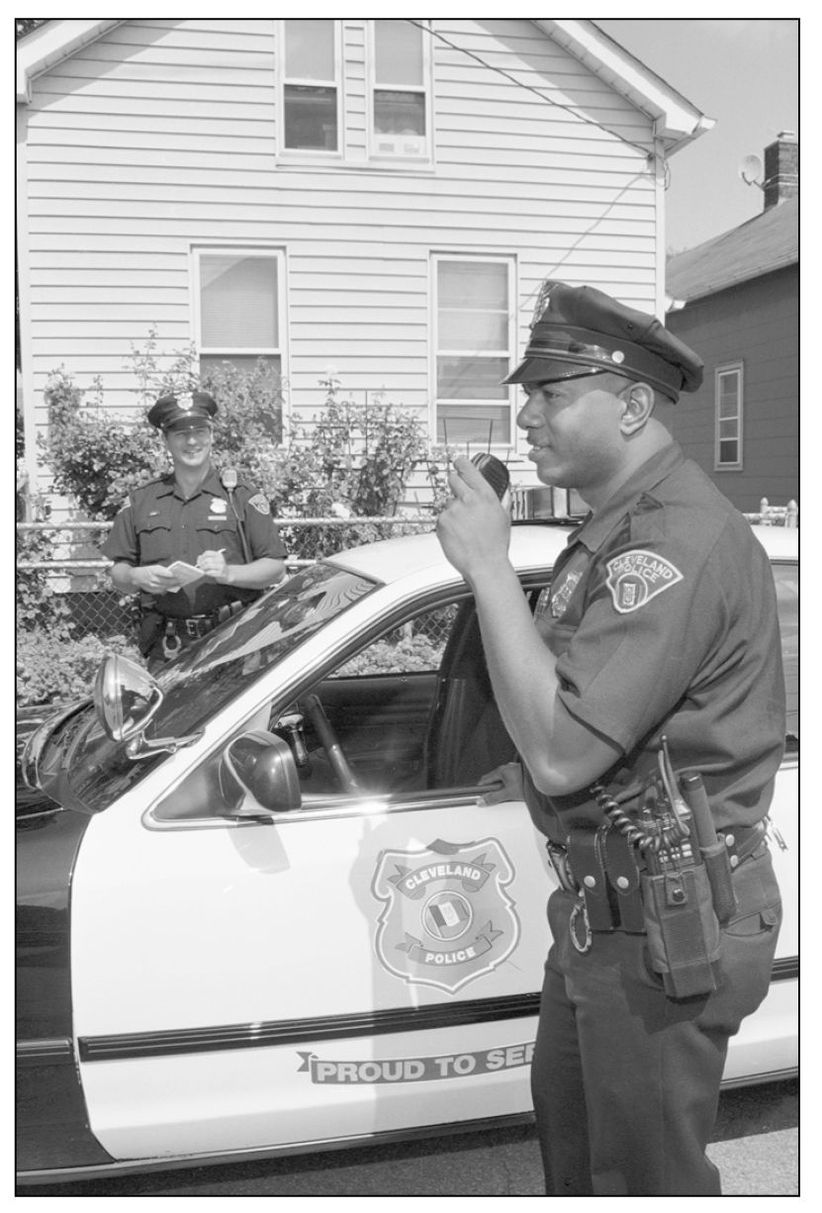

In the 1970s, policewomen and policemen became “patrol officers,” as women were, for the first time, assigned to basic patrol along side their male counterparts. The department’s motto “Our Men Serve All Men” was replaced with “Proud to Serve.” Additionally, increased recruitment of minorities to the department made great strides in making the department more reflective of the racial make up of the city.

During this last part of the 20th century, the friction between the police and the city administration seemed always on the rise. There were police strikes, police lay-offs, and constant confrontations between the mayor’s office and the police department.

The Cleveland Police Department entered the 21st century with hope and confidence. The Cleveland Police Department, which has played a major role in the development of this community, can look to itself with a deep sense of pride, having served a great city for more than 150 years.

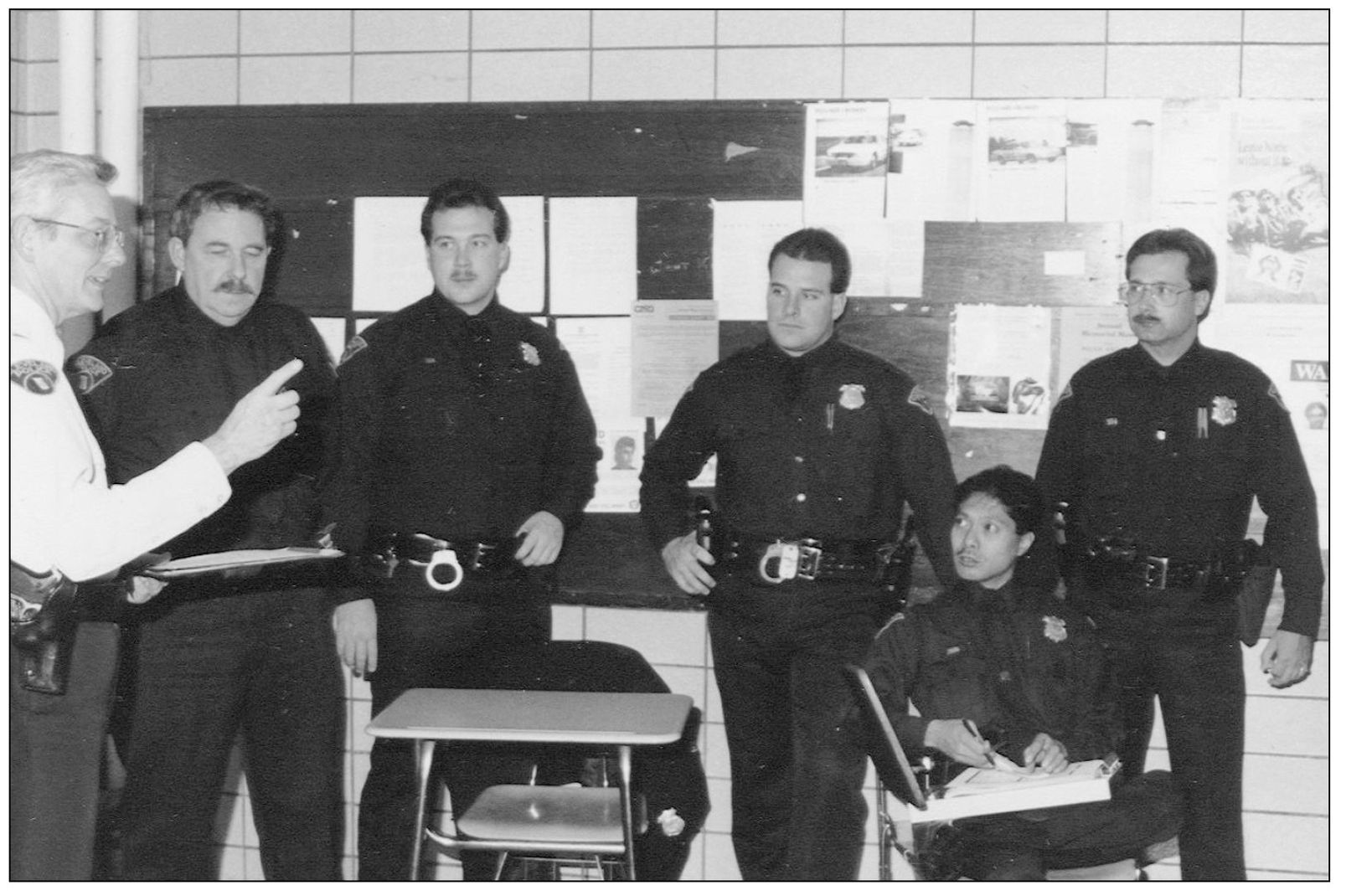

Detectives working out of the Central Station at East 21st and Payne Avenue held roll call on the building’s third floor. Posted in the roll call room were photographs of wanted and suspected criminals, as well as other information—including a poster explaining how to detect marijuana.

The Bureau of Criminal Identification, located in the Central Station, was the central repository for photographs and fingerprints. Although now situated in Police Headquarters in the Justice Center, it continues to be the place victims can go to review “mug shots” in an attempt to identify suspects in crimes.

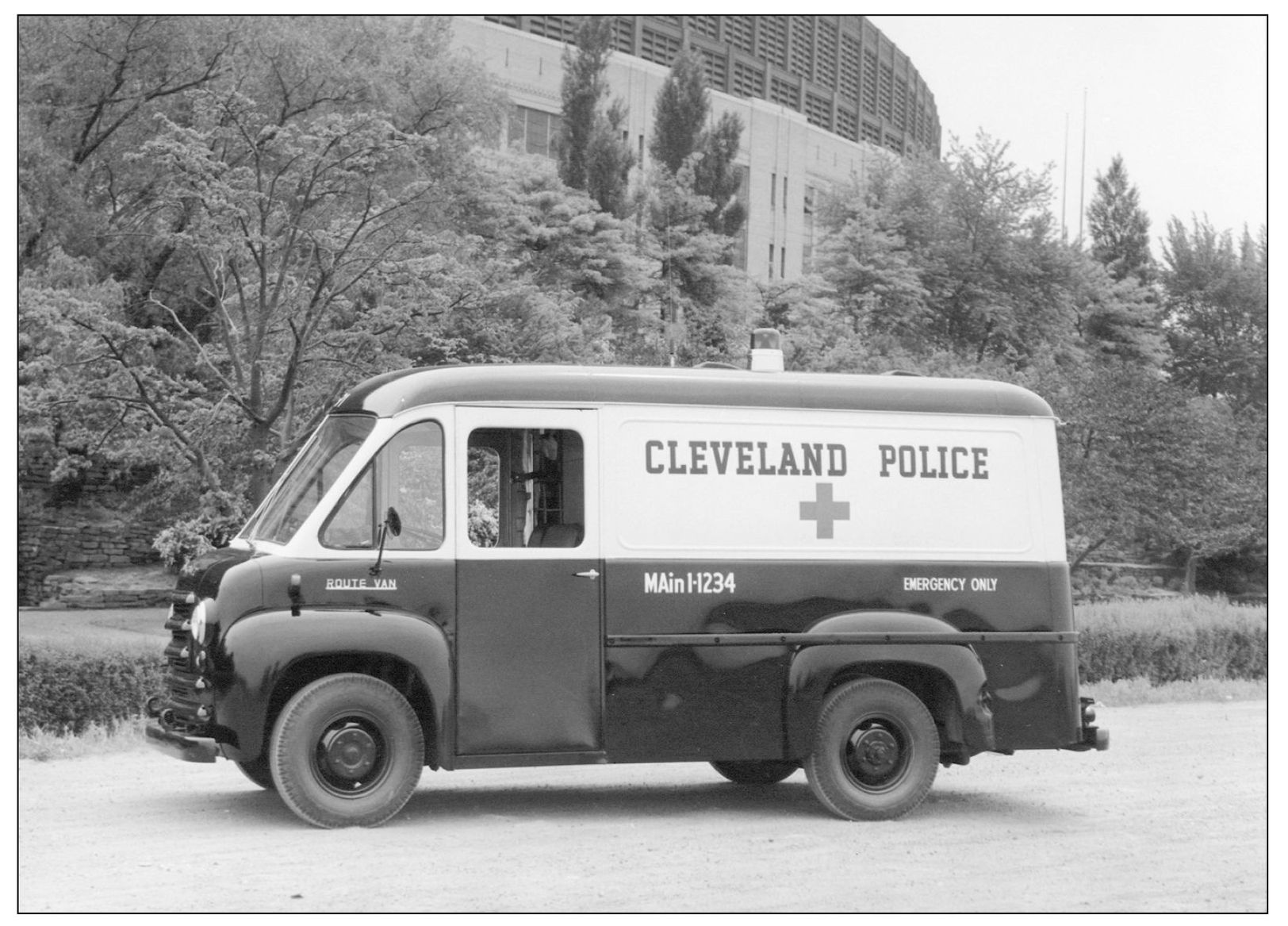

The evolution of the emergency patrol wagon is evident in this roomier and better-equipped Dodge, c. 1955. The wagons were used to haul prisoners to jail and convey the sick and injured to hospitals. Police officers trained in basic first aid continued this tradition until the inception of the Emergency Medical Service in the 1970s. You can still dial MAIN-1-1234 (621-1234) to reach the police operator.

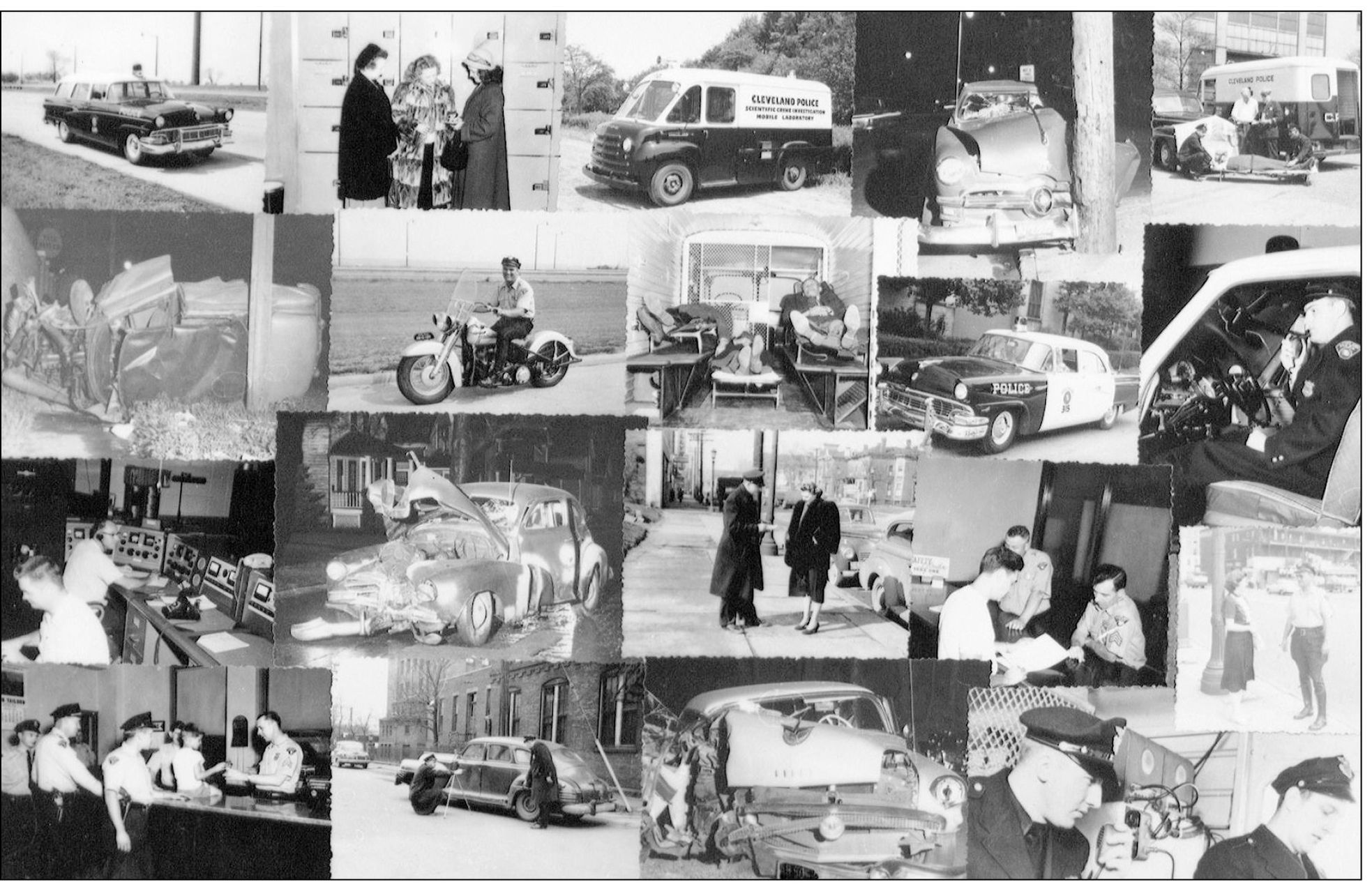

This collage of photographs from the mid-1950s was used to display the various functions of the police department.

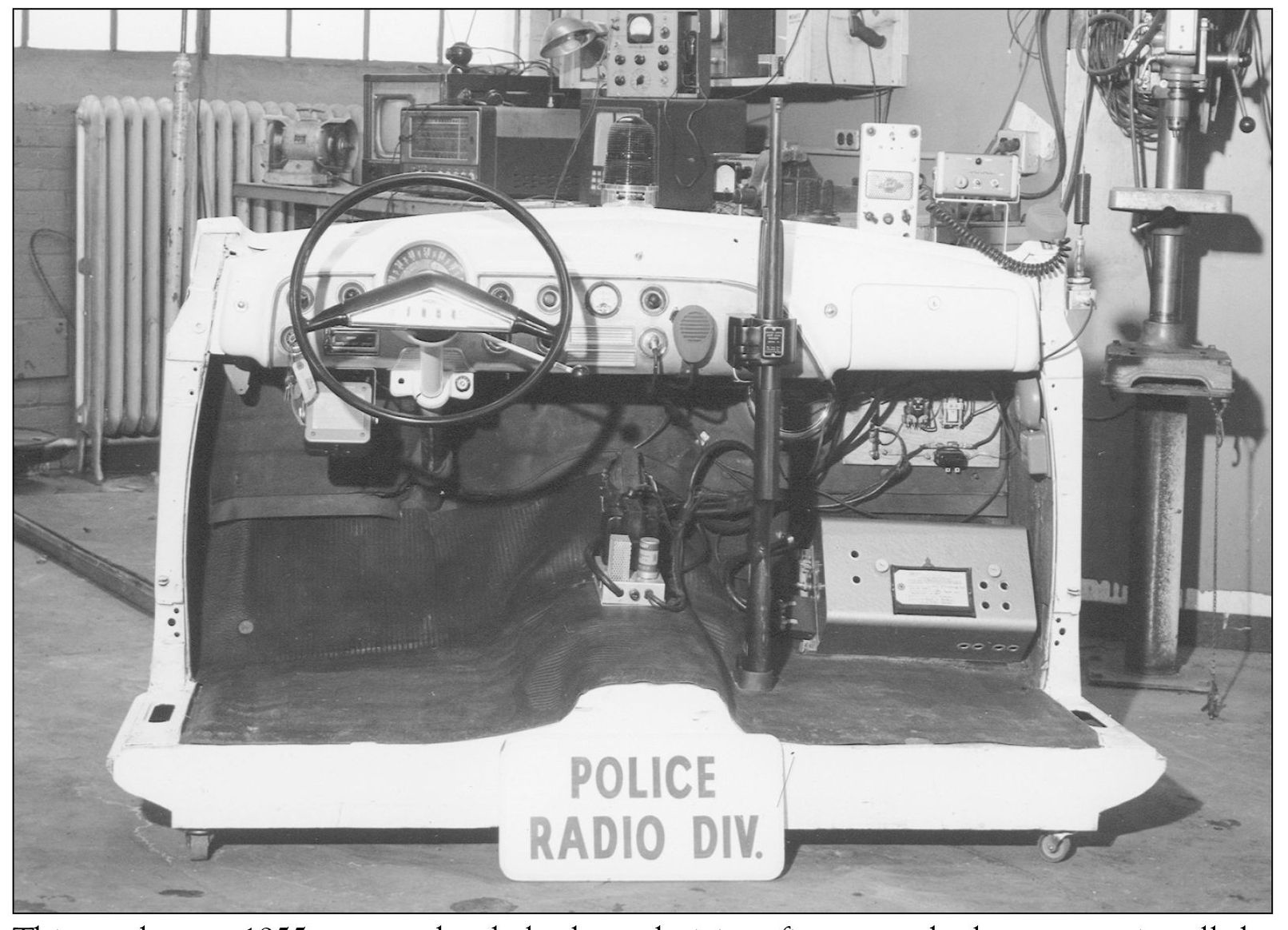

This mockup, c. 1955, was used to help the technicians figure out the best way to install the latest radio equipment into patrol cars.

Third District zone car 315, a 1956 Ford Police Interceptor, was equipped with a new and improved radio system, which included a “six-meter” whip antenna. Previously the antennae were hidden away under the car.

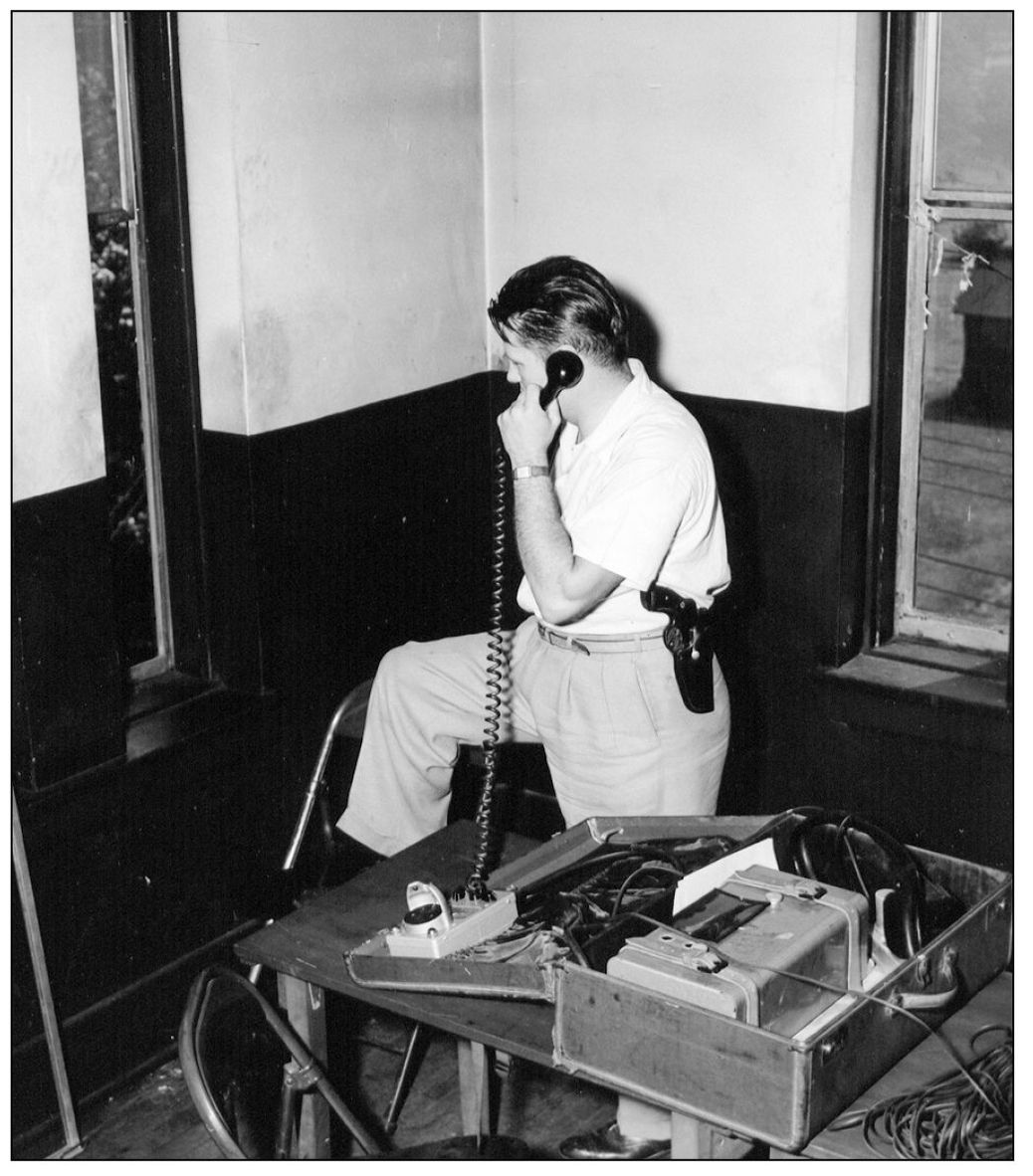

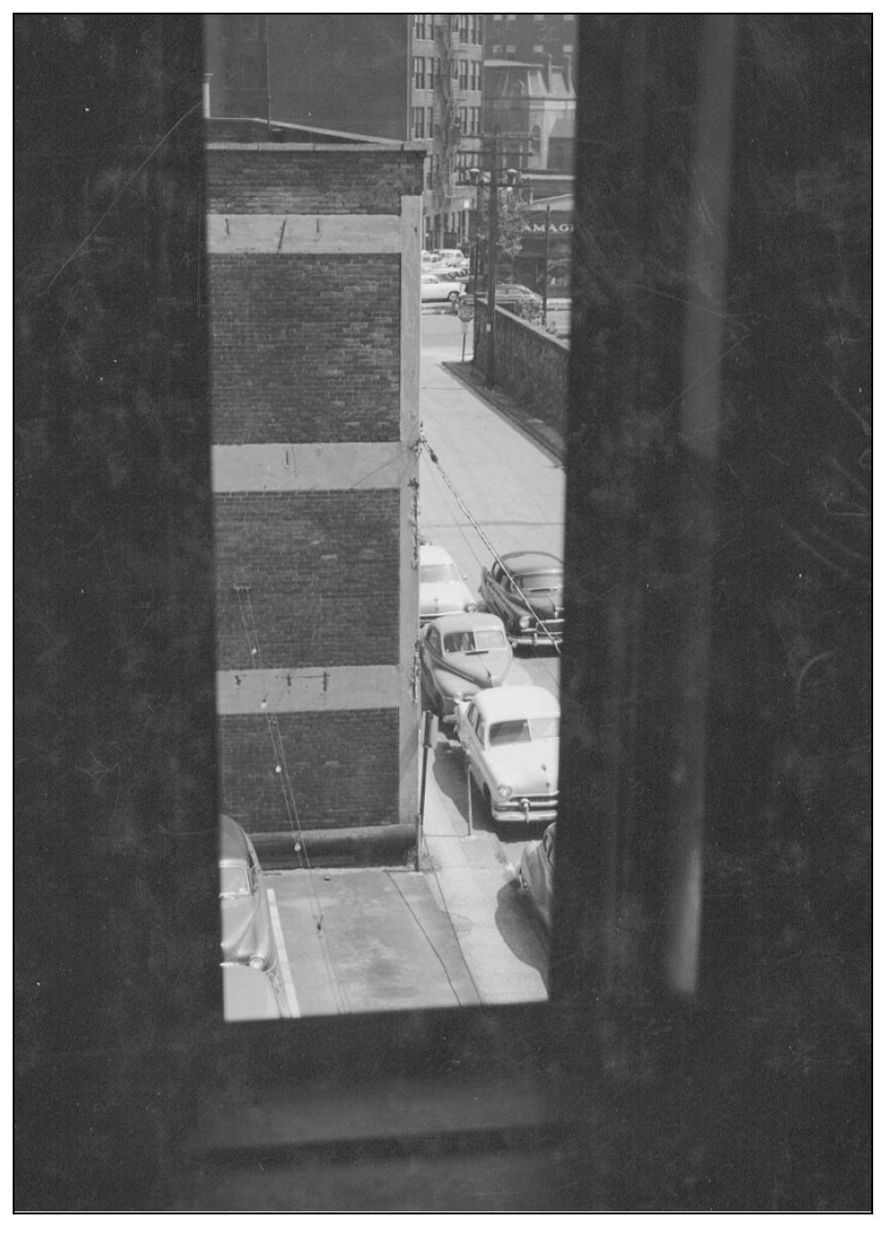

In an effort to keep crime in check, police everywhere employ the “stake out” to surveil and arrest criminals. In these photographs, c. 1956, the police officer in “the perch” keeps an eye on the street below, where numerous cars had been broken into.

The suspects were unaware they were being watched, photographed, and surrounded by undercover police officers.

Caught completely off guard, the suspects were placed in police custody moments after they made their break-in to the automobile.

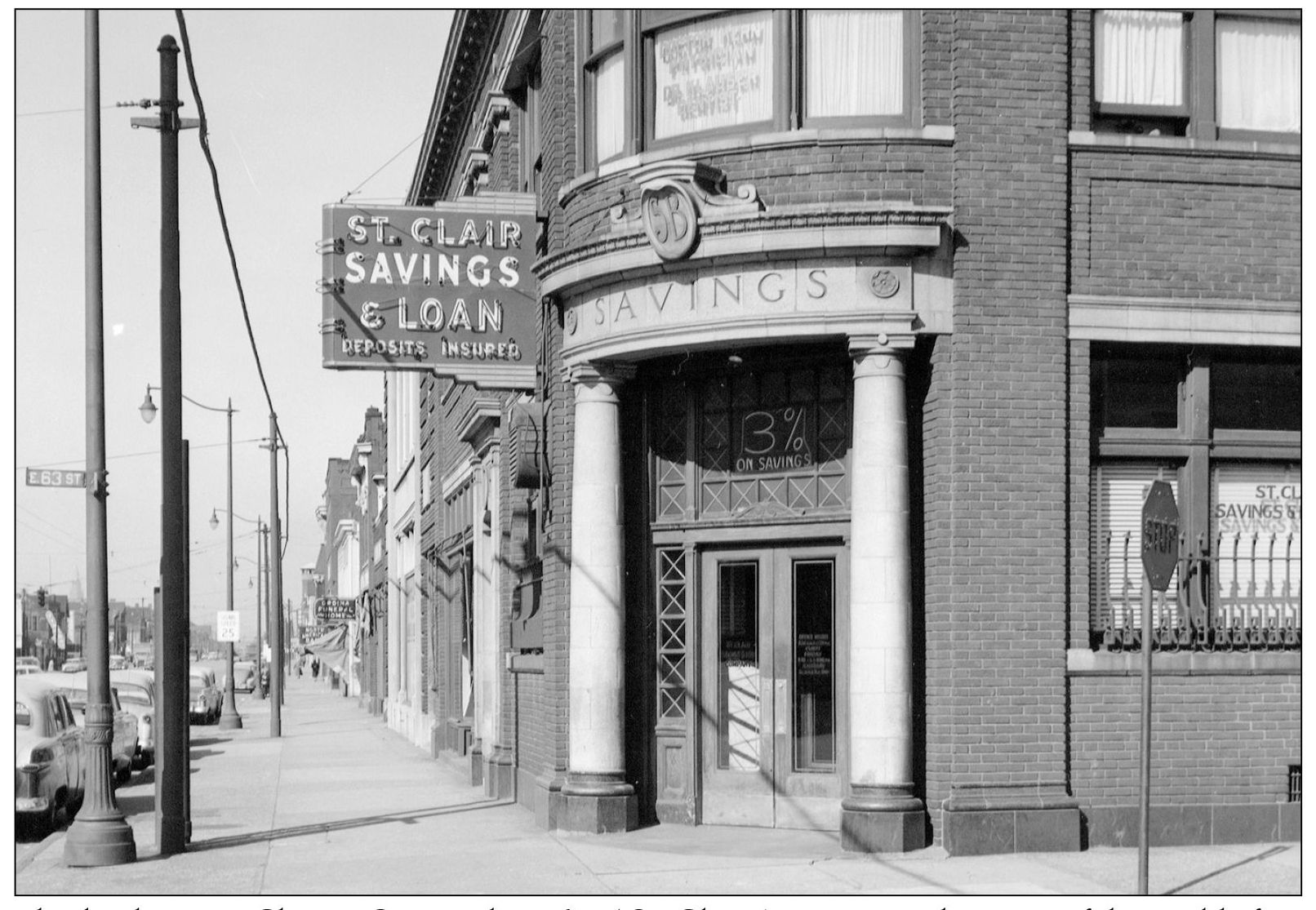

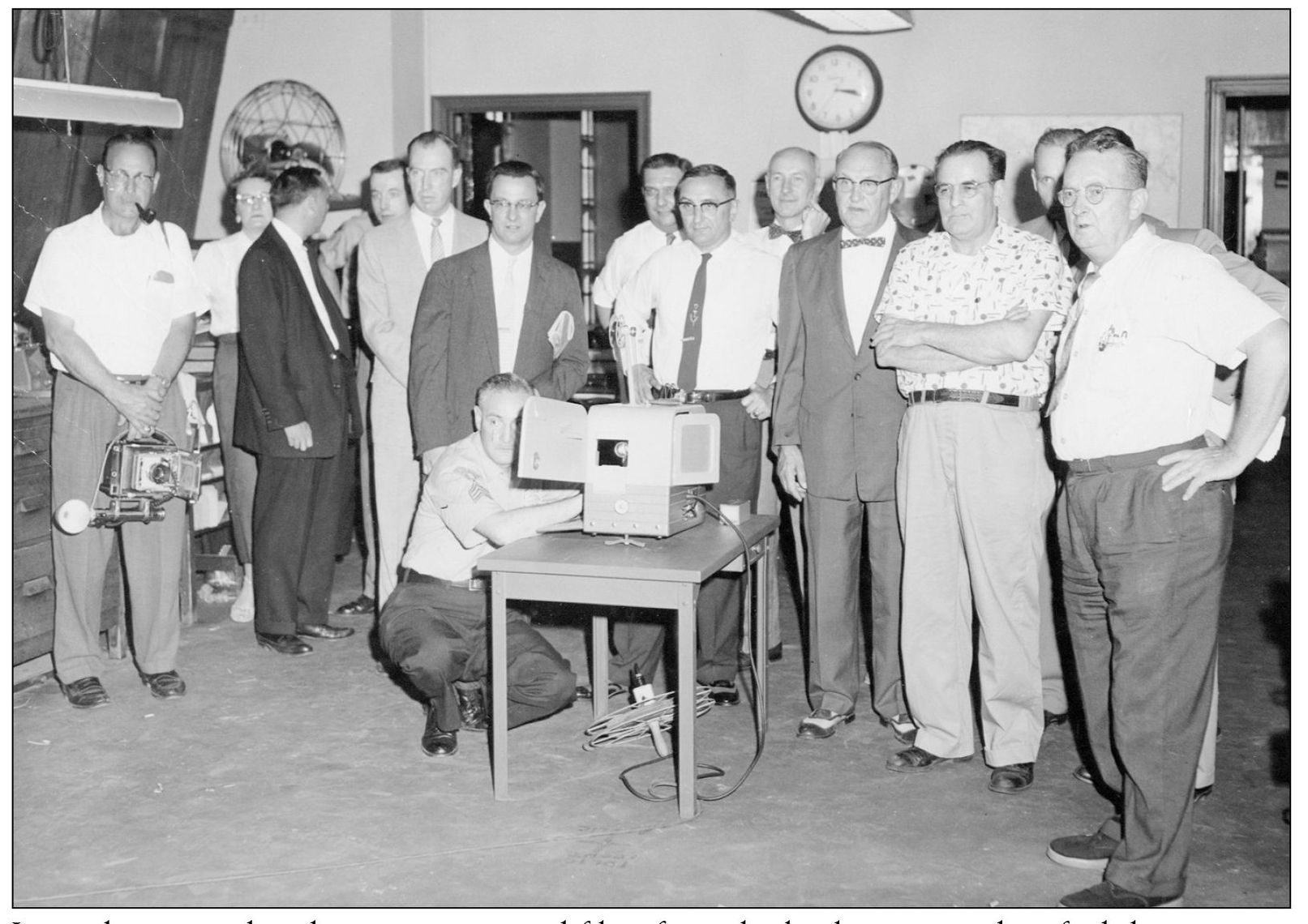

This bank, now a Charter One Bank, at 6235 St. Clair Avenue, was the scene of the world’s first bank robbery to be filmed by a bank security camera. The robbery occurred shortly after noon, April 12, 1957. Son of Police Chief Frank Story and superintendent of police communications, Thomas E. Story is displaying the camera.

Later that same day, detectives reviewed films from the bank camera, identified the suspects, and broadcast the footage on the national news. By combining good detective work and the use of this new technology, the suspects were soon arrested.

The three robbery suspects, awaiting their arraignment with doom in their eyes, read of their demise at the hands of the Cleveland Police Department.

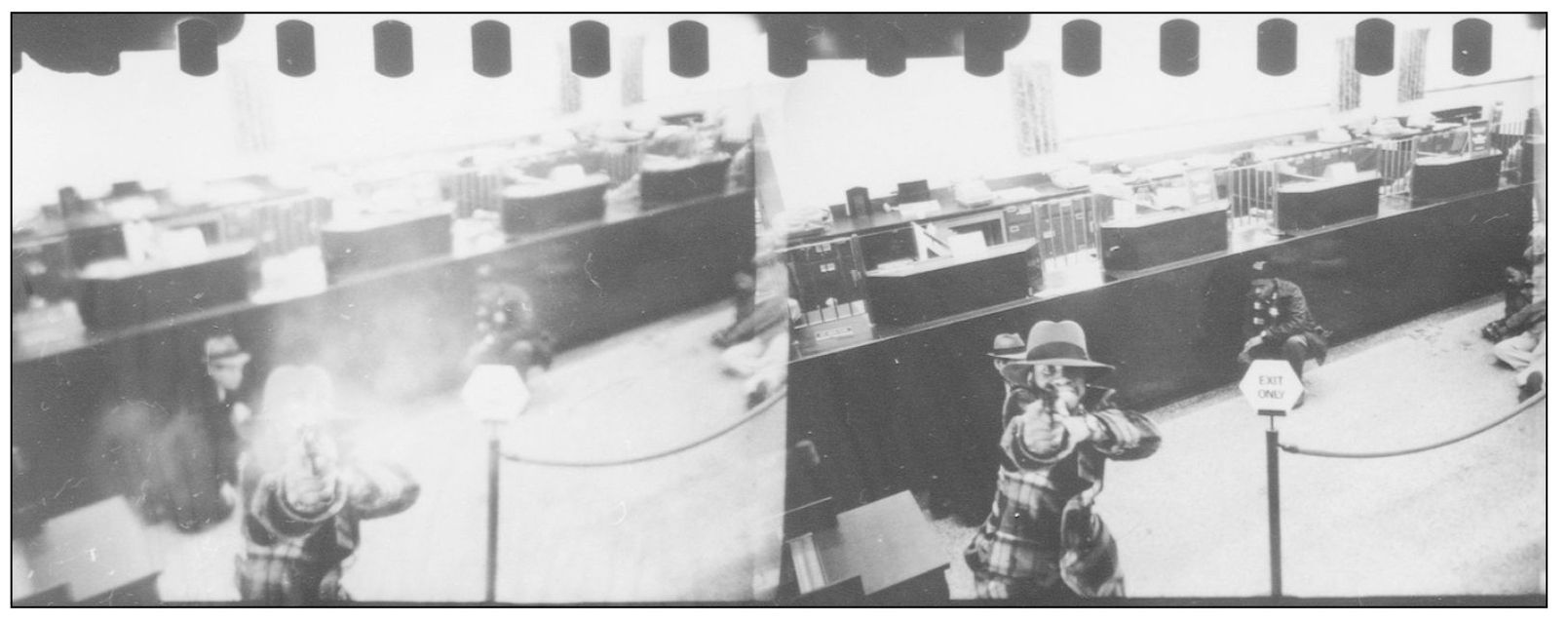

Although blurry, this frame from the actual film depicts the male suspect pointing his gun across the teller window where his accomplice, the woman in the dark coat, helps herself to the bank’s money.

“No stick-up man in his right mind will walk into a bank with a hidden camera peering at him out of a wall” said Chief Frank Story, April 12, 1957. Proving this statement to be overly optimistic, a robber attempts to disable this camera by shooting at it, c. 1970.

In 1959, these women were training with firearms. They are under the watchful eye of Lieut. Michael Roth, far right. The police women, from left to right, are Ruby Scott, Ruth May, Patricia Cozens, Jean Aber, and Joanne Timkovic.

The Cleveland Police Department’s Marching Unit prepares for the annual St. Patrick’s Day Parade on March 17, 1962.

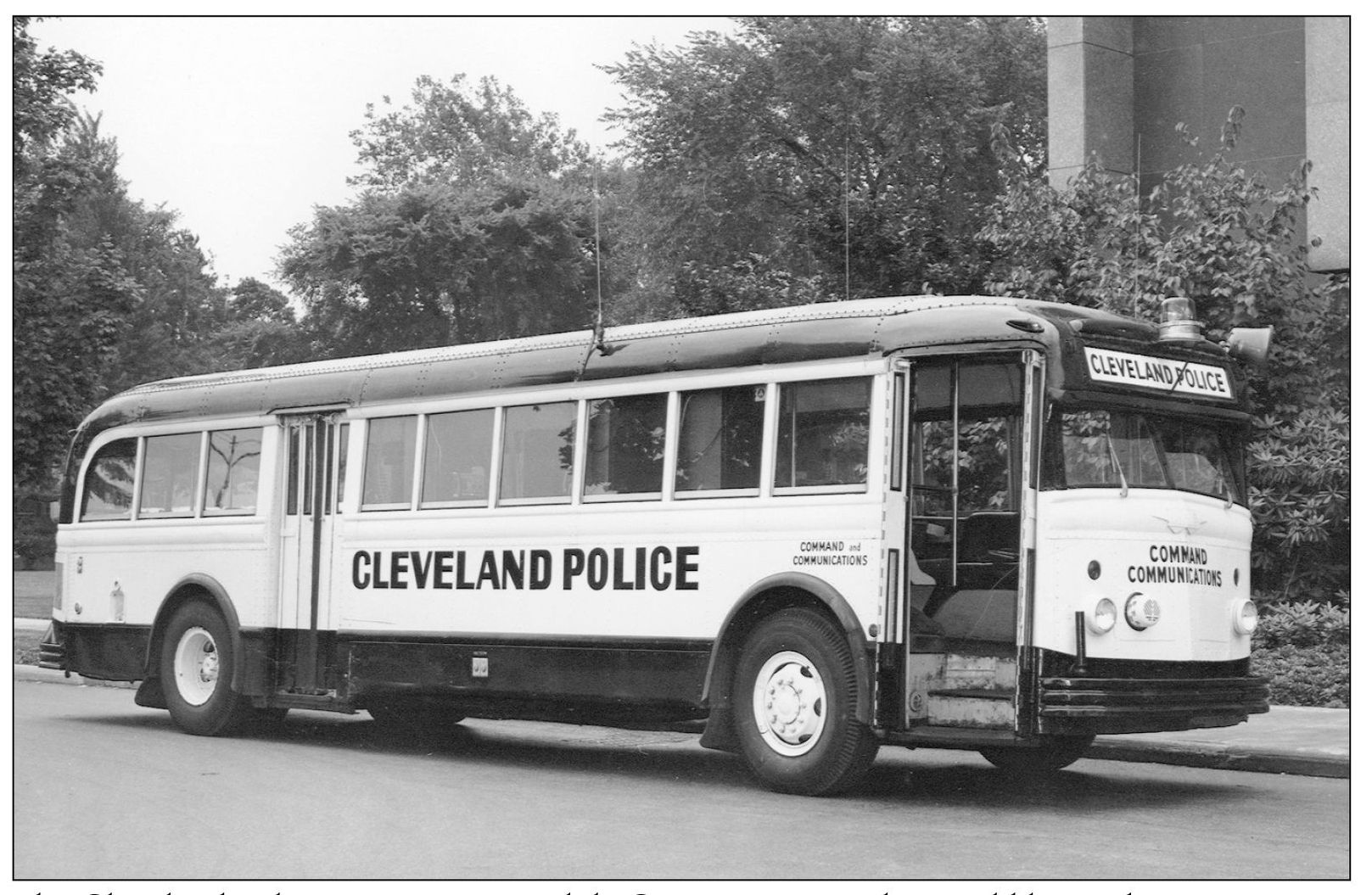

The Cleveland Police Department Mobile Communications bus could be used at remote sites and for large-scale special operations. It is pictured here around 1963.

On July 4, 1963, the communications bus was deployed for the Independence Day celebration. The staff included, left to right, Capt. Pete Becker, unknown, Patrolman Anton S. Lohn #93, Superintendent Tom Story, Katherine Sutkow, unknown, and Policewoman Susan Boyd #3006.

On October 31, 1963, Det. Martin McFadden, age 62 with 39 years on the job, confronted three men acting suspiciously in front of a downtown shop. The three men were detained by McFadden, and when he patted them down to check for weapons, he launched a case that went on to the Supreme Court of the United States as “Terry v. Ohio,” which became a hallmark for every law enforcement officer since.

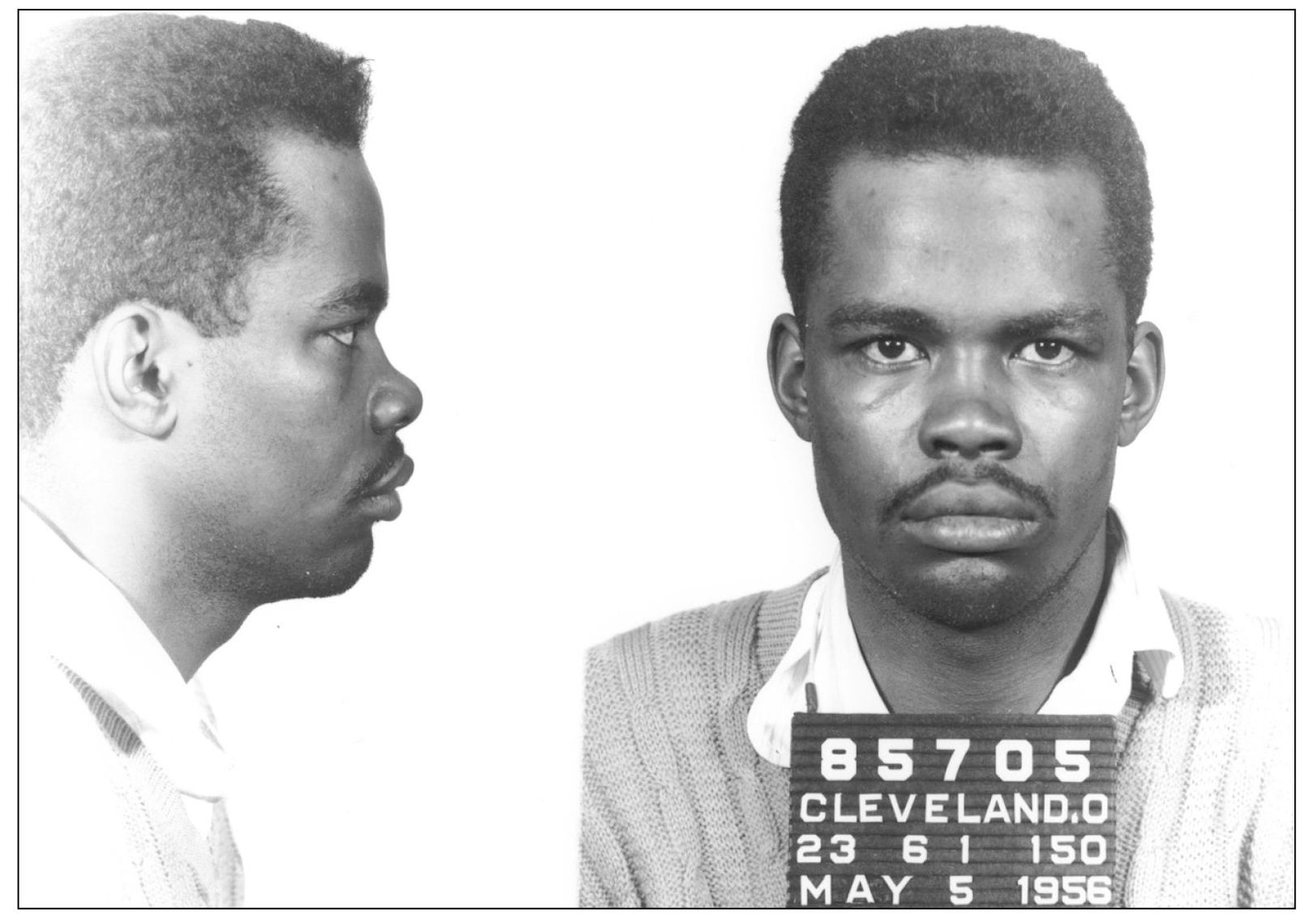

John Woodall Terry, a career criminal, and two accomplices were preparing to rob a downtown store when Detective McFadden confronted them. Even by the time this mug shot was made in 1956, Terry had the proverbial “rap sheet as long as your arm.”

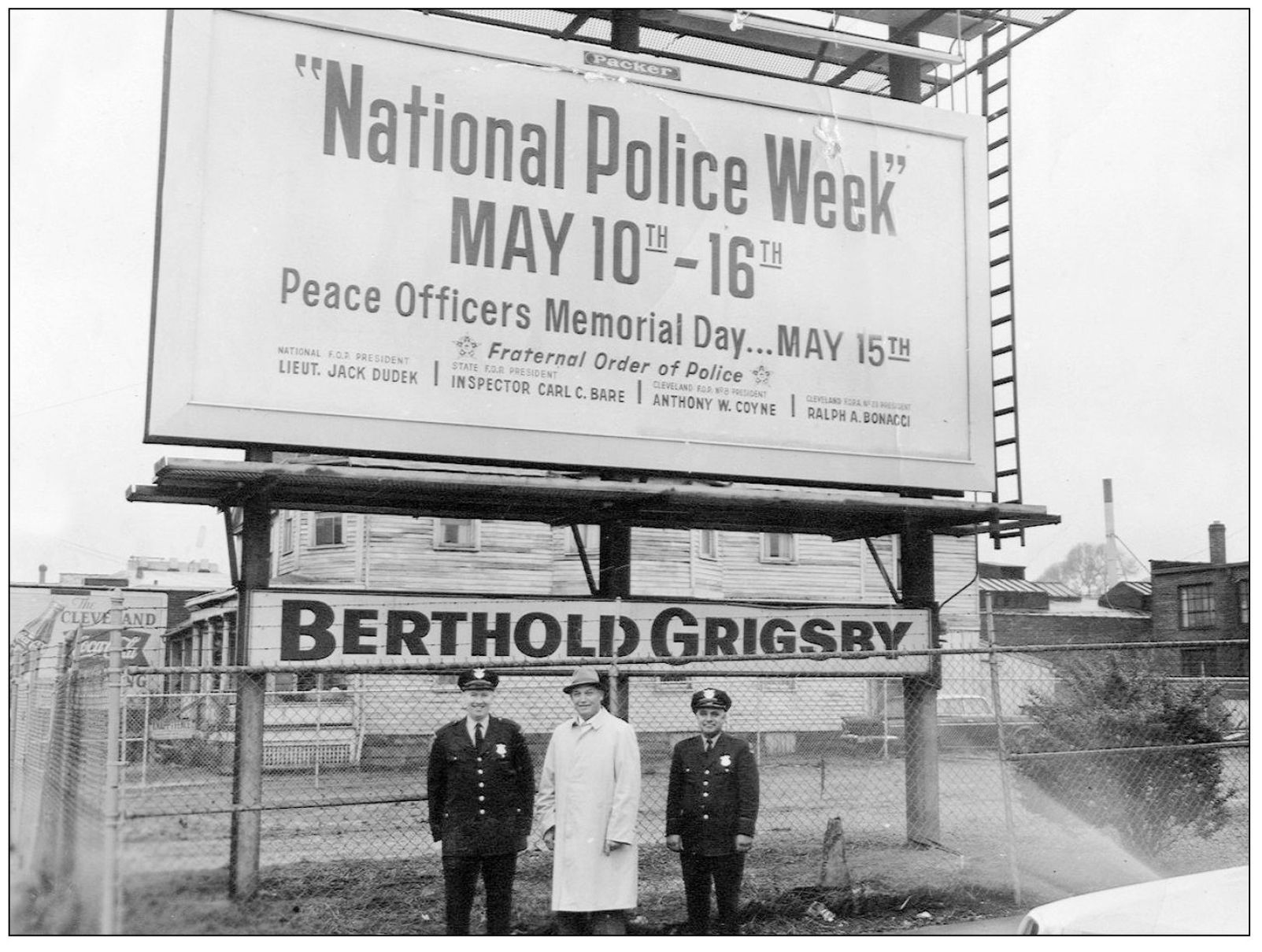

Sergt. Anthony Coyne, president of FOP Lodge number eight; Deputy Inspector Carl C. Bare, state FOP president; and Ralph A. Bonacci, CPD Tow Unit and president of FOPA no. 23; ensured that the public was aware of the first annual celebration of National Police Week and Peace Officers Memorial Day, as proclaimed by President John F. Kennedy in 1963.

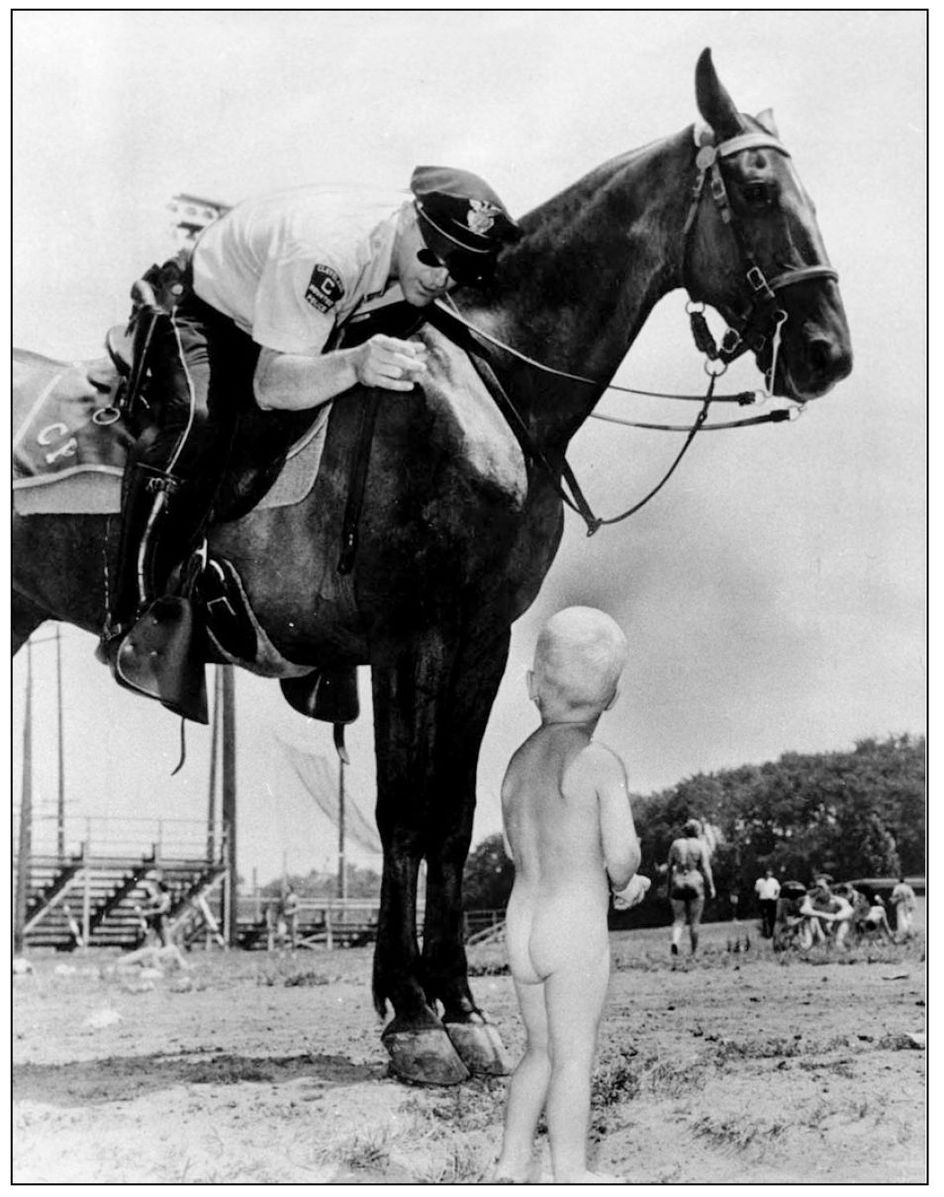

Prior to the widespread use of suntan lotion, this member of the Cleveland Police Mounted Unit warns this young beachcomber to cover up.

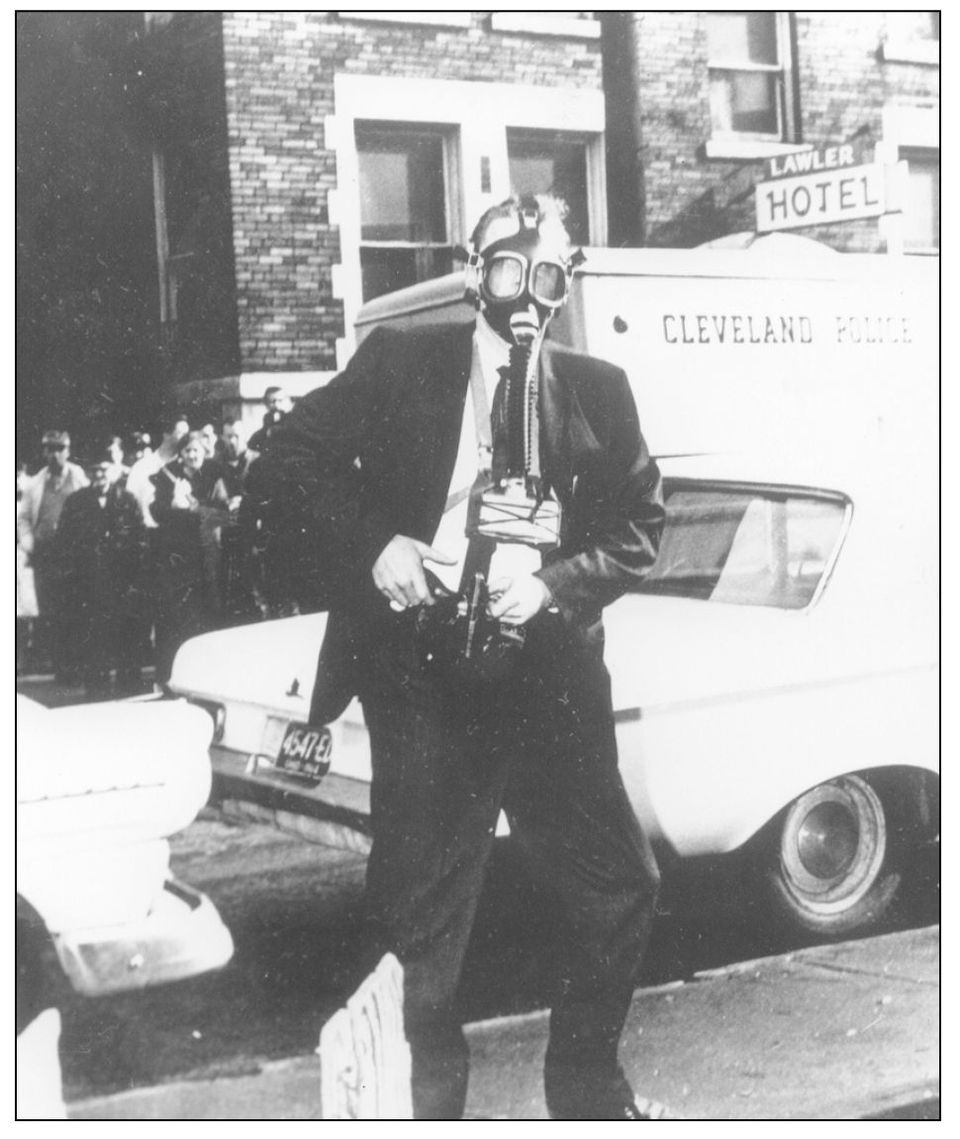

Det. Robert F. Shankland prepares for the use of tear gas at an incident at East 19th Street and Payne Avenue in 1964.

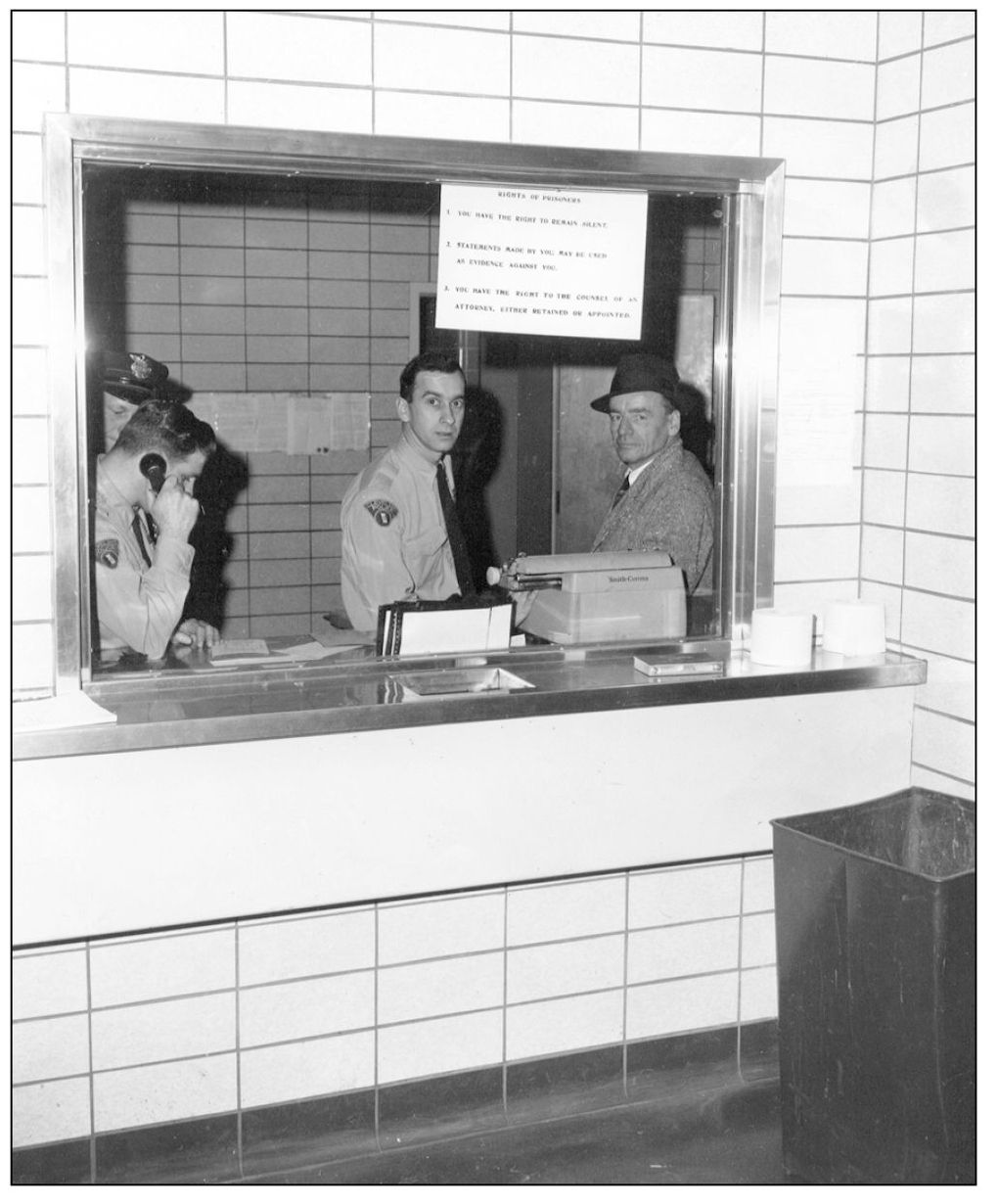

As a response to the Supreme Courts ruling that all suspects were to be advised of their constitutional rights before any questioning, the “Miranda Warning” was posted at the Fifth District booking window. From left to right are Patrolman James V. DiFranco #218, Patrolman Casimir S.Roszak#943, and Detective O’Donnell.

Local and national celebrities loved to work with the Cleveland Police Department, either under the protection of a security detail or on a public education/community relations campaign. Before he began his long-running television variety show, Gene Carroll was a broadcaster for WJMO-Radio. Here he is with Patrolman Patrick E. Cooney #289, c. 1949.

Ron Penfound, host of the Captain Penny Show (1955–1971), is seen here with Cleveland police officers including Patrolman William D. Schueneman #439, the motorcycle officer on the left.

Talk show host Mike Douglas helped promote a public relations campaign with Patrolman Elmer Goltz #511 and Patrolman Charles J. Brynak Jr. #1121.

National variety show host Ed Sullivan greets members of the Cleveland Police Mounted Unit, including Patrolman Arthur Lettieri #876, center.

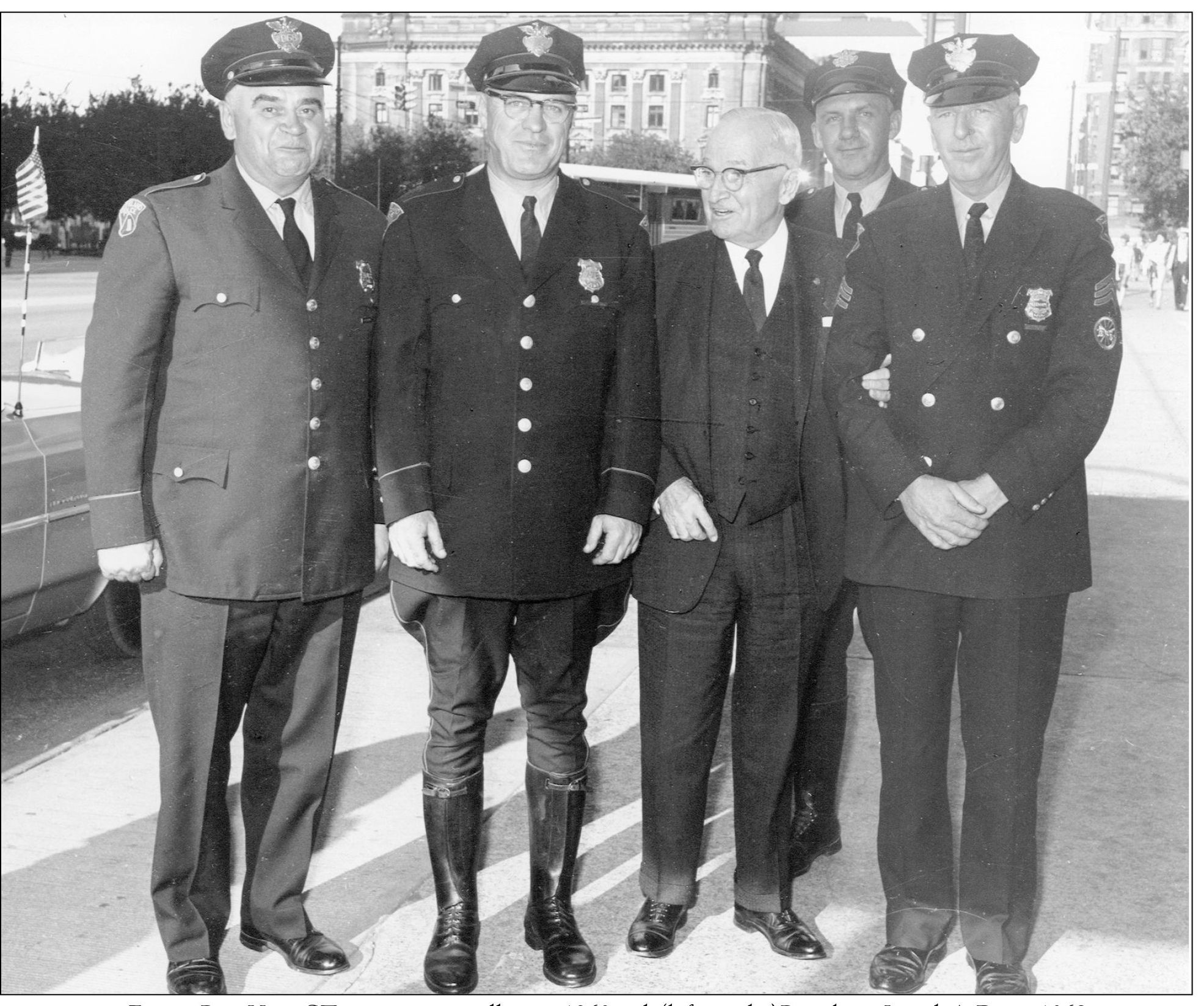

FormerPres.HarrySTrumanispicturedhere in 1960with(lefttoright) PatrolmanJosephA.Dura#1068, Patrolman Edward R. Misencik #776, Patrolman Leo Hayes #1249, and Sergt. Patrick Gallagher.

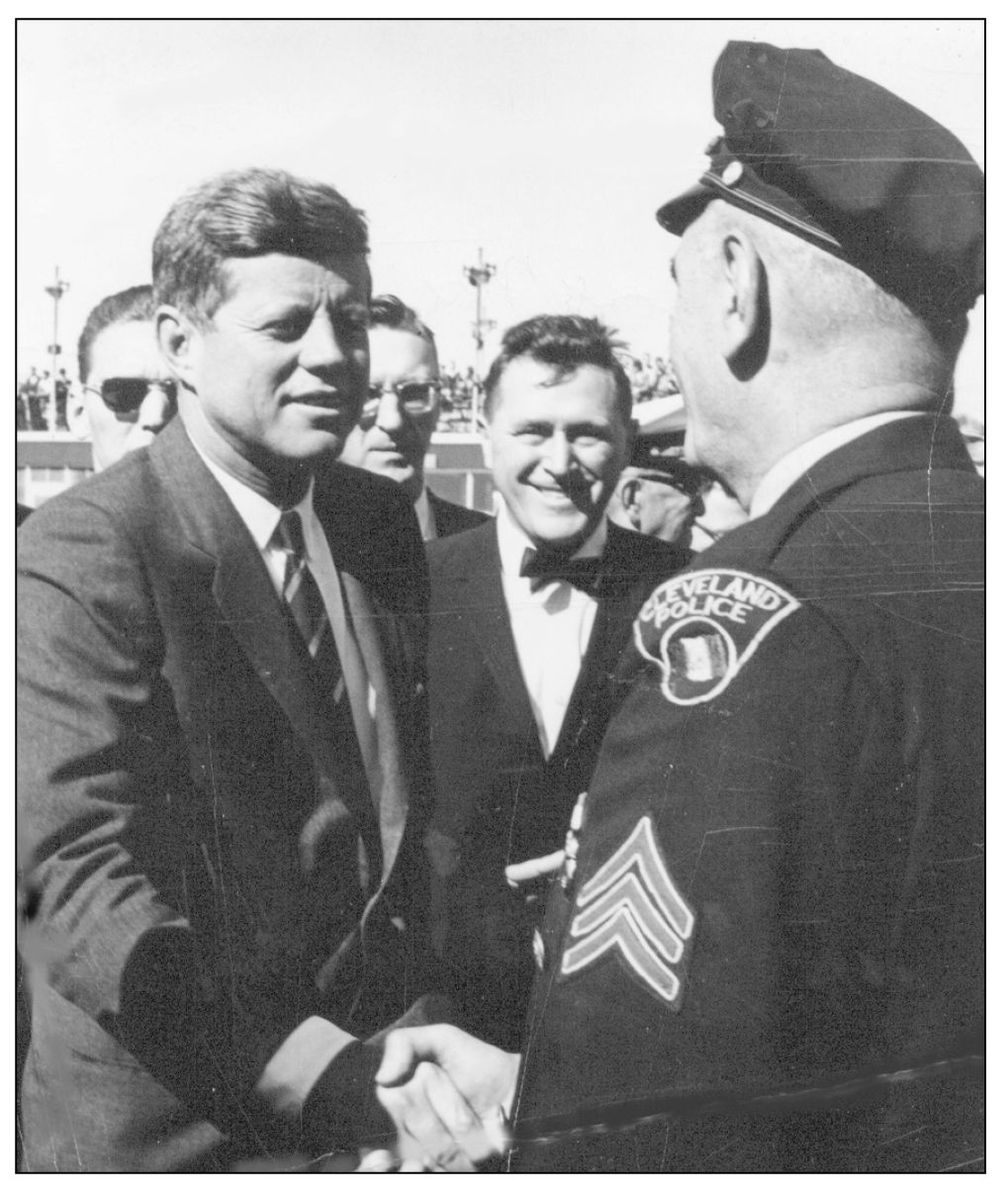

Cleveland Police Sergt. Anthony Nachtigal, president of the Fraternal Order of Police Lodge number eight, meets Pres. John F. Kennedy at Hopkins Airport during a pres idential visit in October of 1962.

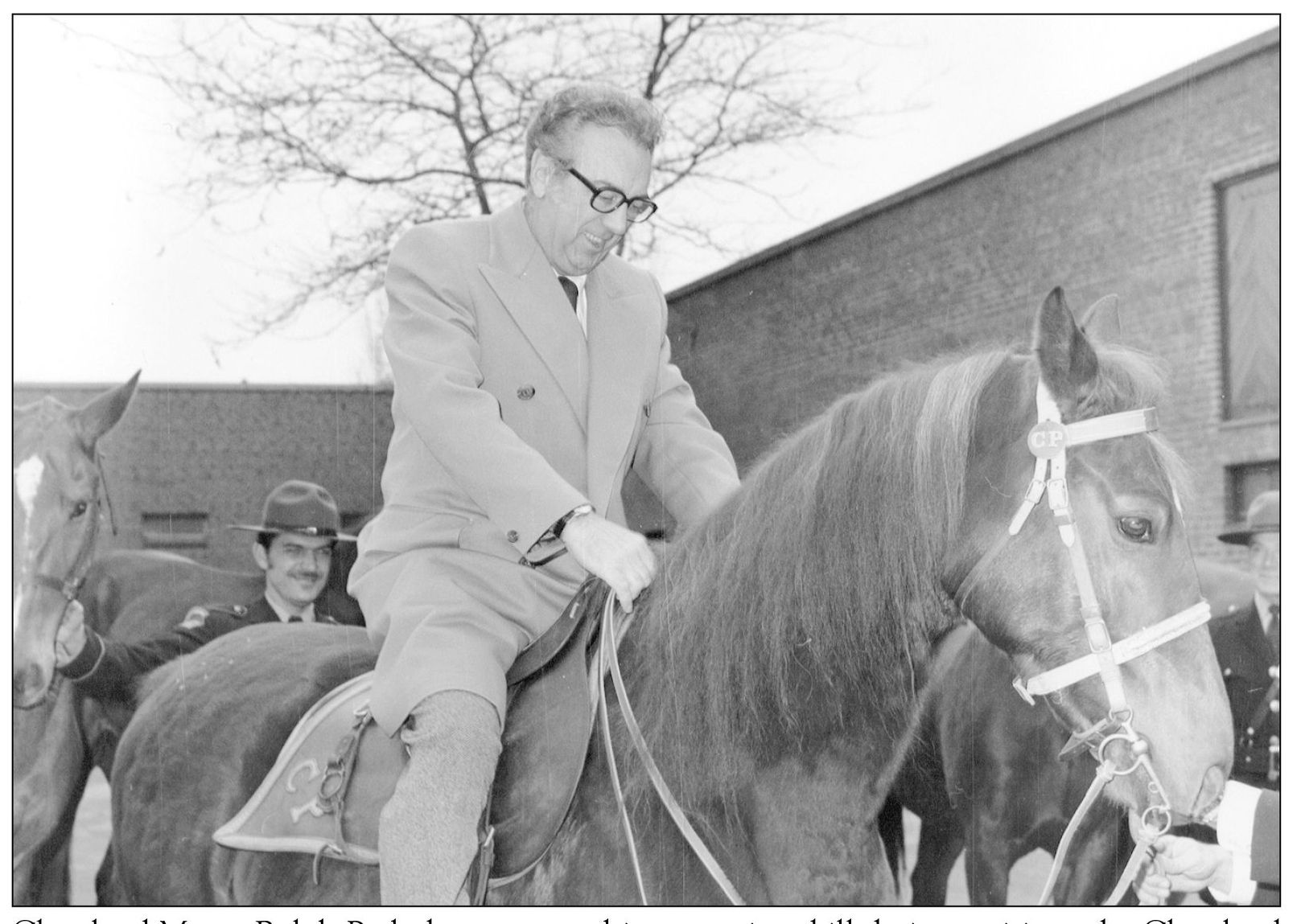

Cleveland Mayor Ralph Perk demonstrates his equestrian skill during a visit to the Cleveland Police Mounted Unit, c. 1973.

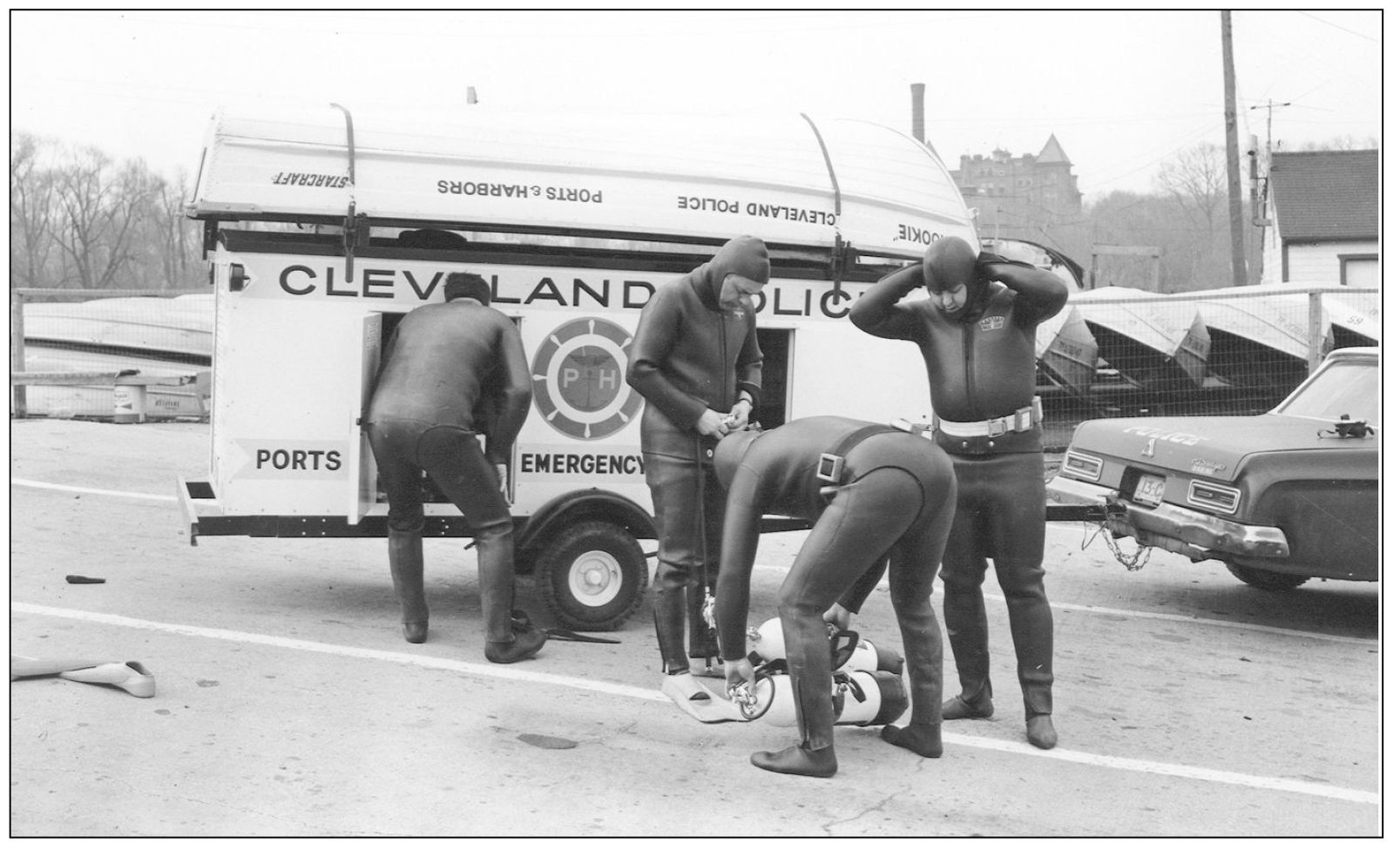

With the use of their mobile equipment trailer, members of the Cleveland Police Ports and Harbors Unit are able respond to water-related emergencies at inland lakes and streams and along the shoreline, where their larger patrol boats are unable to reach.

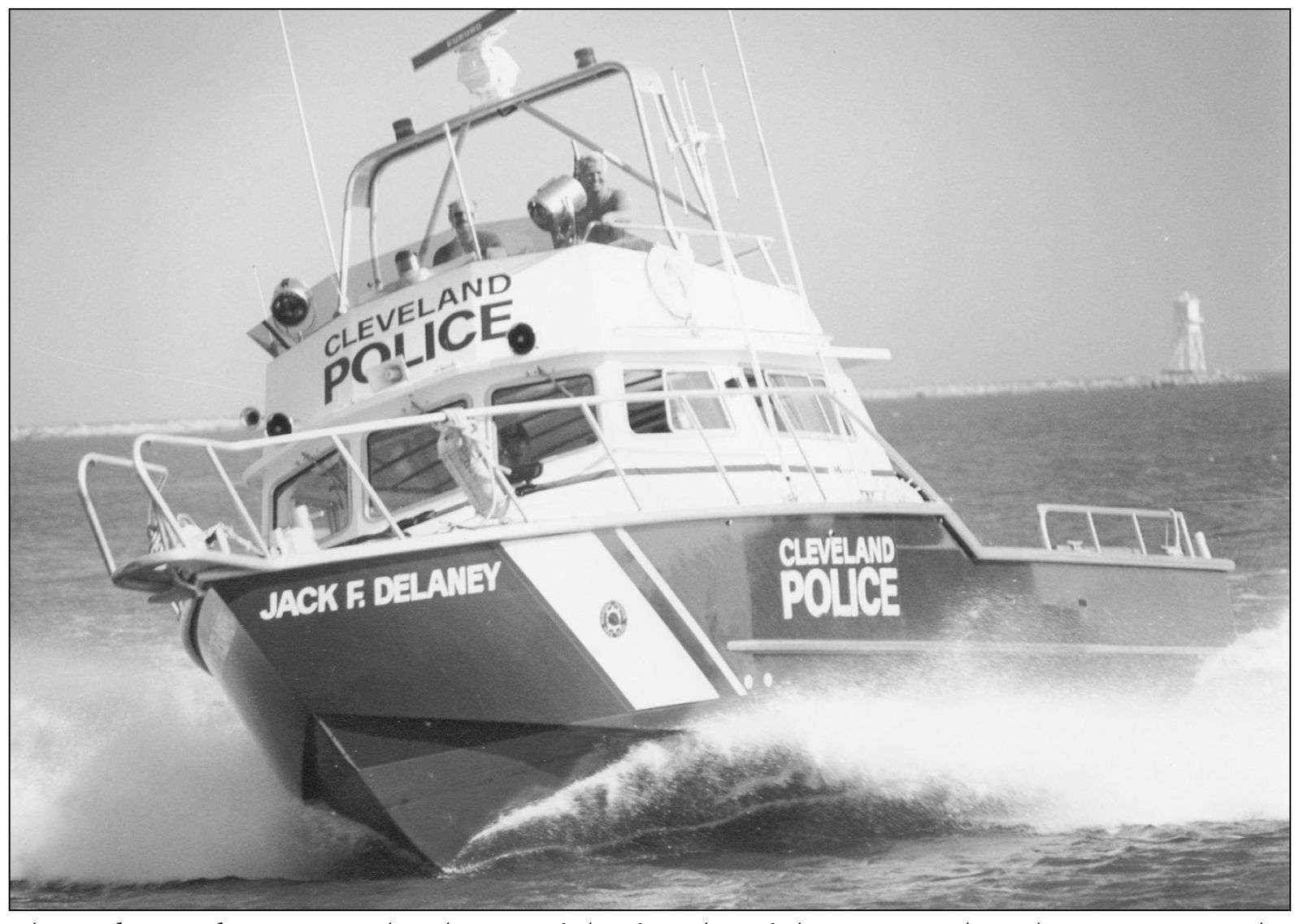

The Lex (Latin for “law”) was designed by Cleveland Police Lieut. John “Jack” Delaney, the first officer in charge of the Ports and Harbors Unit. Launched in 1963, the Lex, which is still in service, was built by the Inland Seas Boat Company of Sandusky, Ohio.

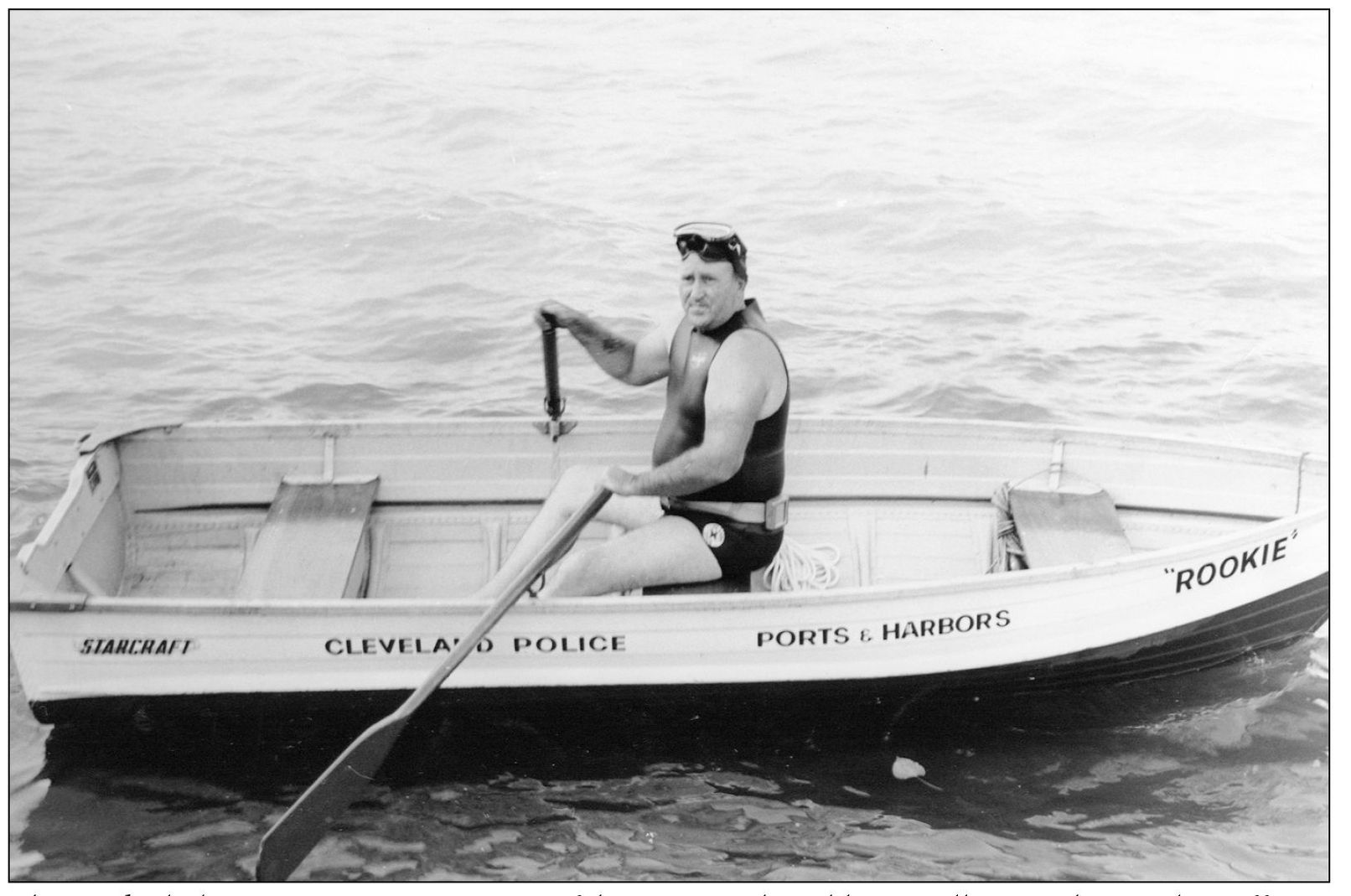

The Rookie belies its name, as it was one of the unit’s real workhorses allowing these police officers to get closer to the target when performing rescues and recoveries. Patrolman Richard E. Ryan#573 is at the oars.

The Bluecoat, obtained in 1964 and smaller and faster than the Lex, was an additional tool to be used by the Ports and Harbors Unit in their quest to make the water a safe place to enjoy.

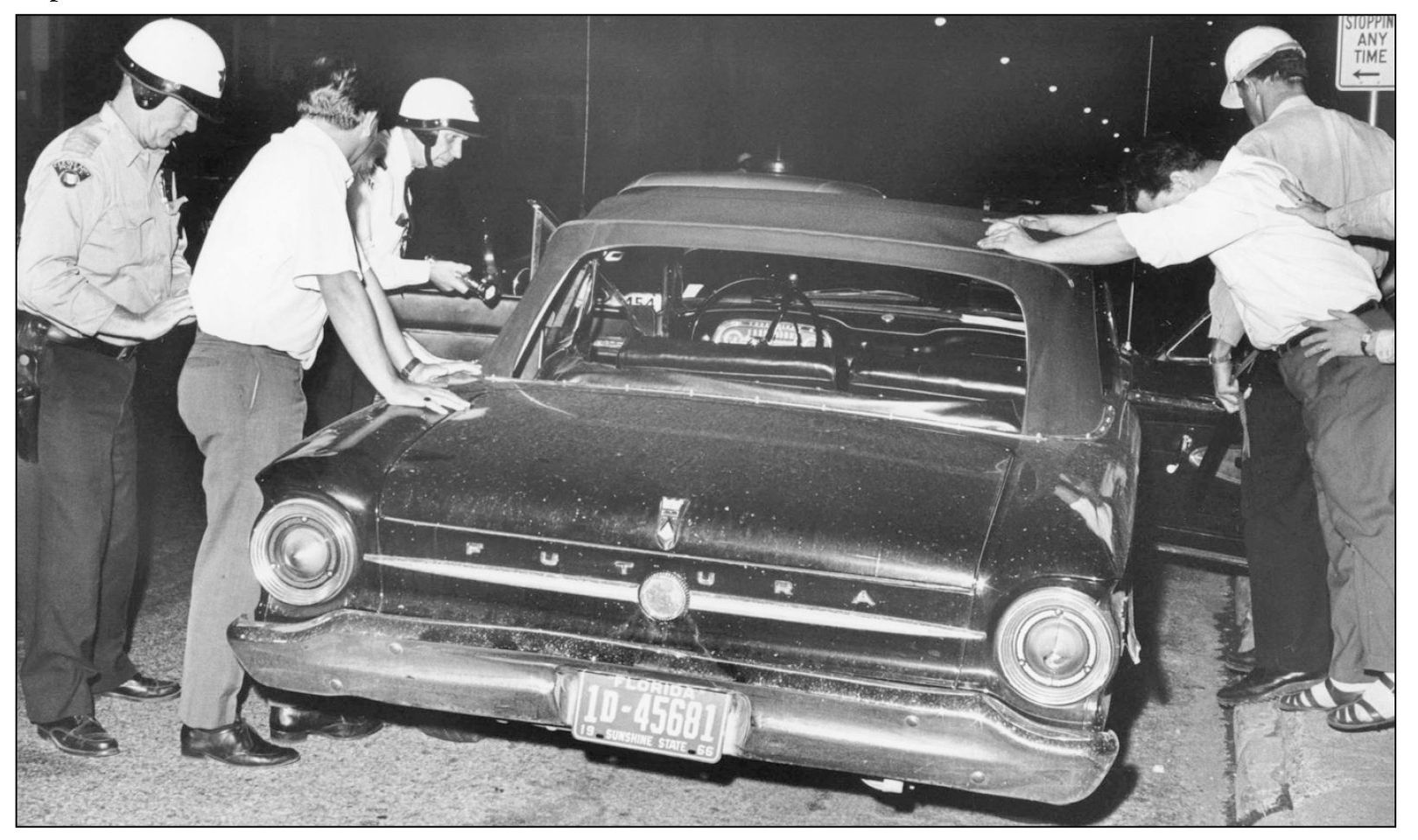

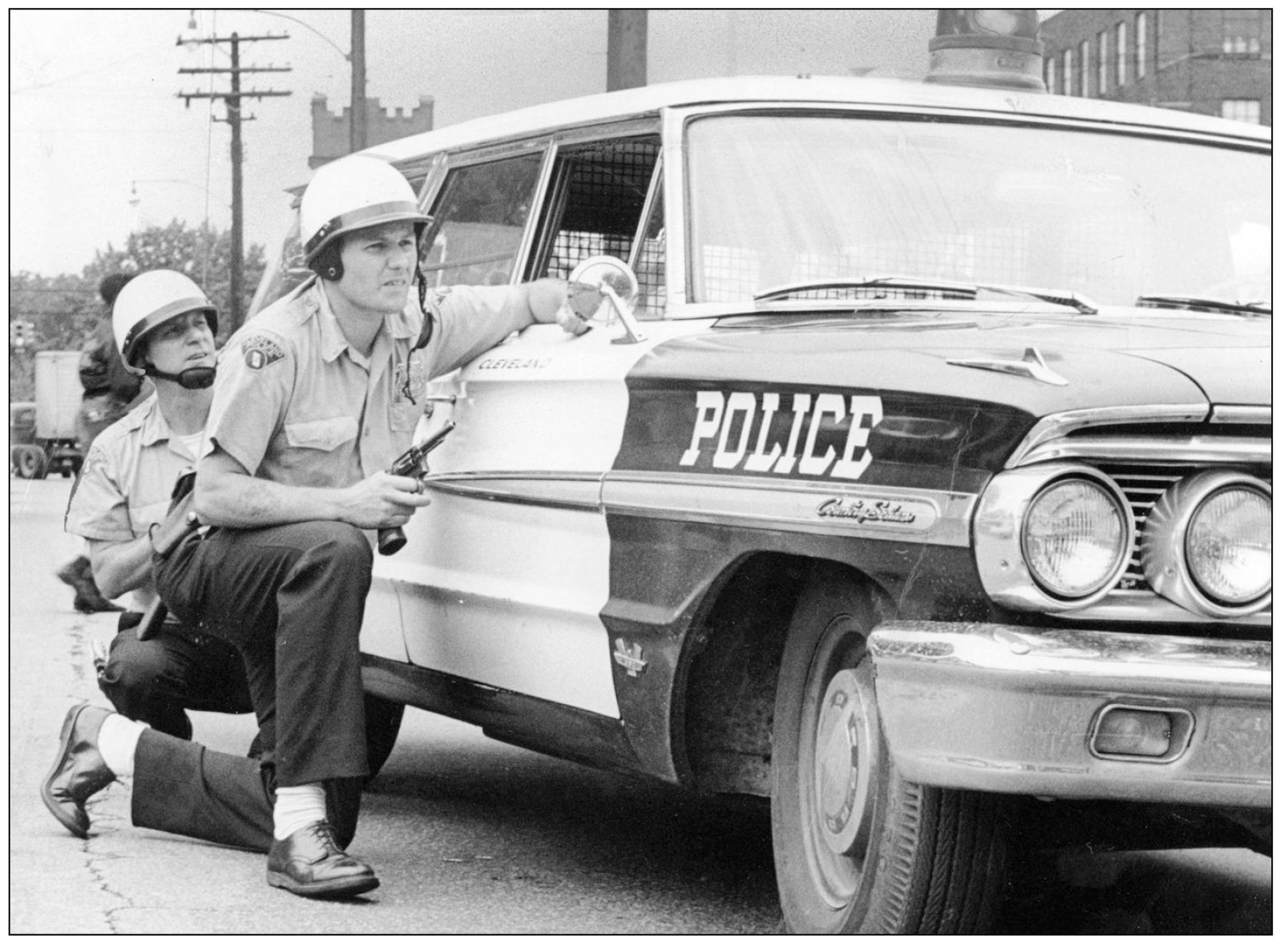

The Cleveland Police Department was put to its limit in the summer of 1966 when the Hough neighborhood erupted in violence. The Ohio National Guard was called in to help the department restore order.

The Hough riots drew national attention. Additional agitators prone to violence from outside of the city, as well as the curious, were drawn to the riot area.

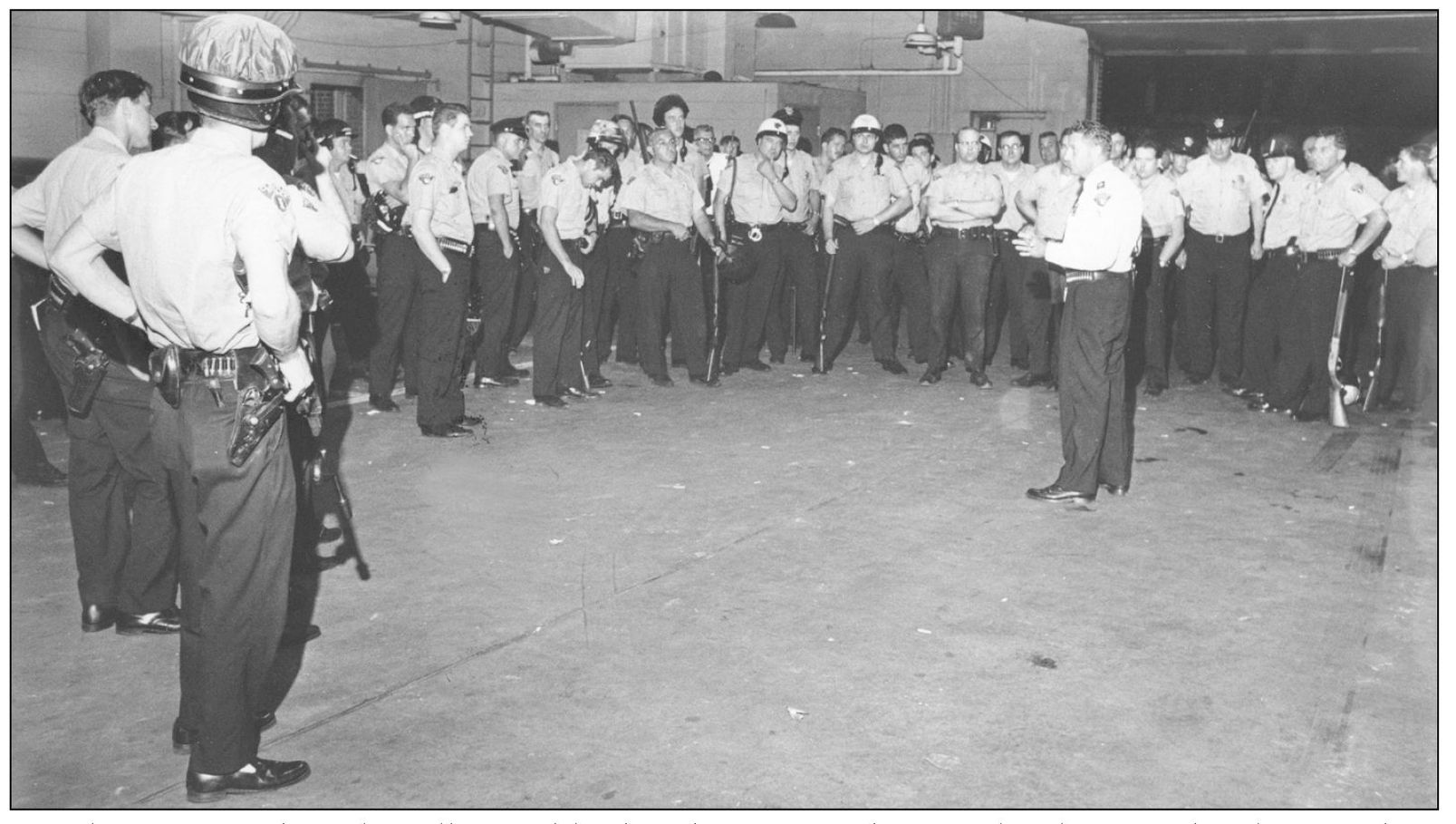

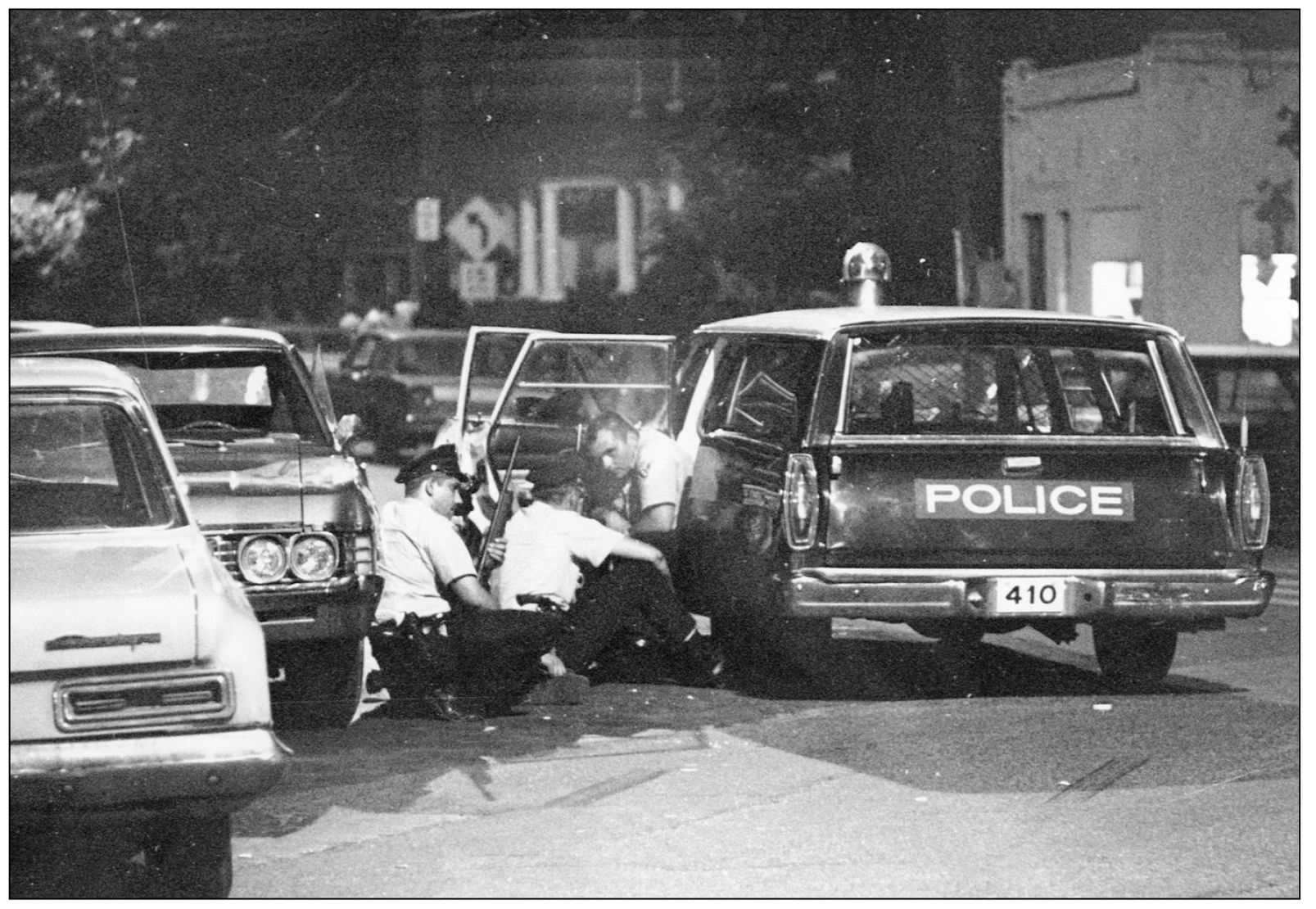

In July of 1968, the Glenville neighborhood was turned into a battle zone that began when three police officers were killed in an ambush that eventually led to several days of rioting. These heavily armed police officers assemble for roll call at the Fifth District.

Police officers from throughout the city responded to the call for help when the rioting began.

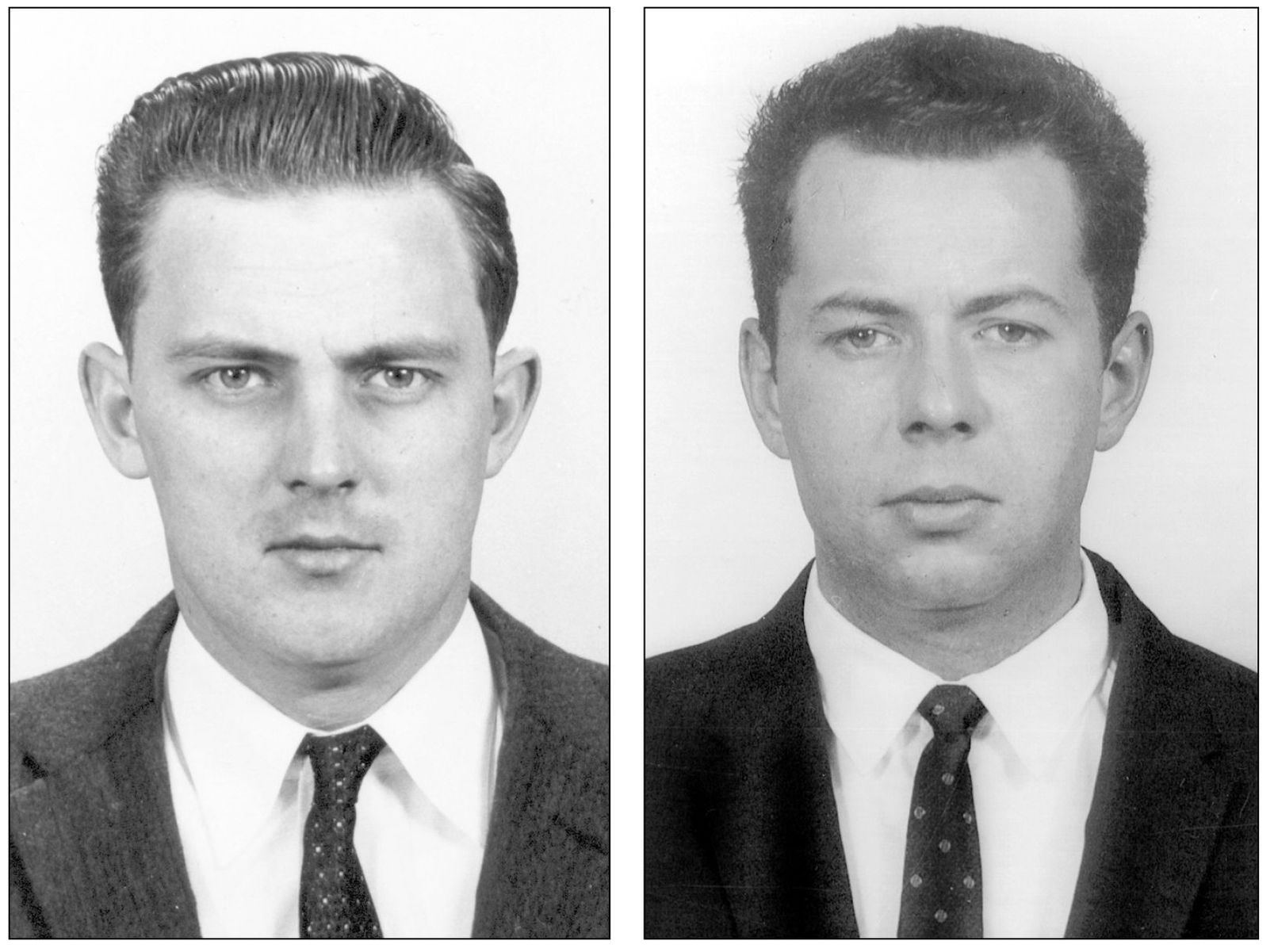

Lieut. Leroy Jones (left), Patrolman Louis Golonka #1831 (lower left), and Patrolman Willard Wolff #1740 (lower right) all died of wounds received that day. Patrolman Thomas Smith #1232 died on March 9, 1993, after suffering the effects of his wounds for 25 years. Fourteen other Cleveland Police Officers were injured that day, including 11 that were shot.

In August of 1966, these two Cleveland Police Officers prepare to rush an apartment at 629 Eddy Road in search of a bank robber.

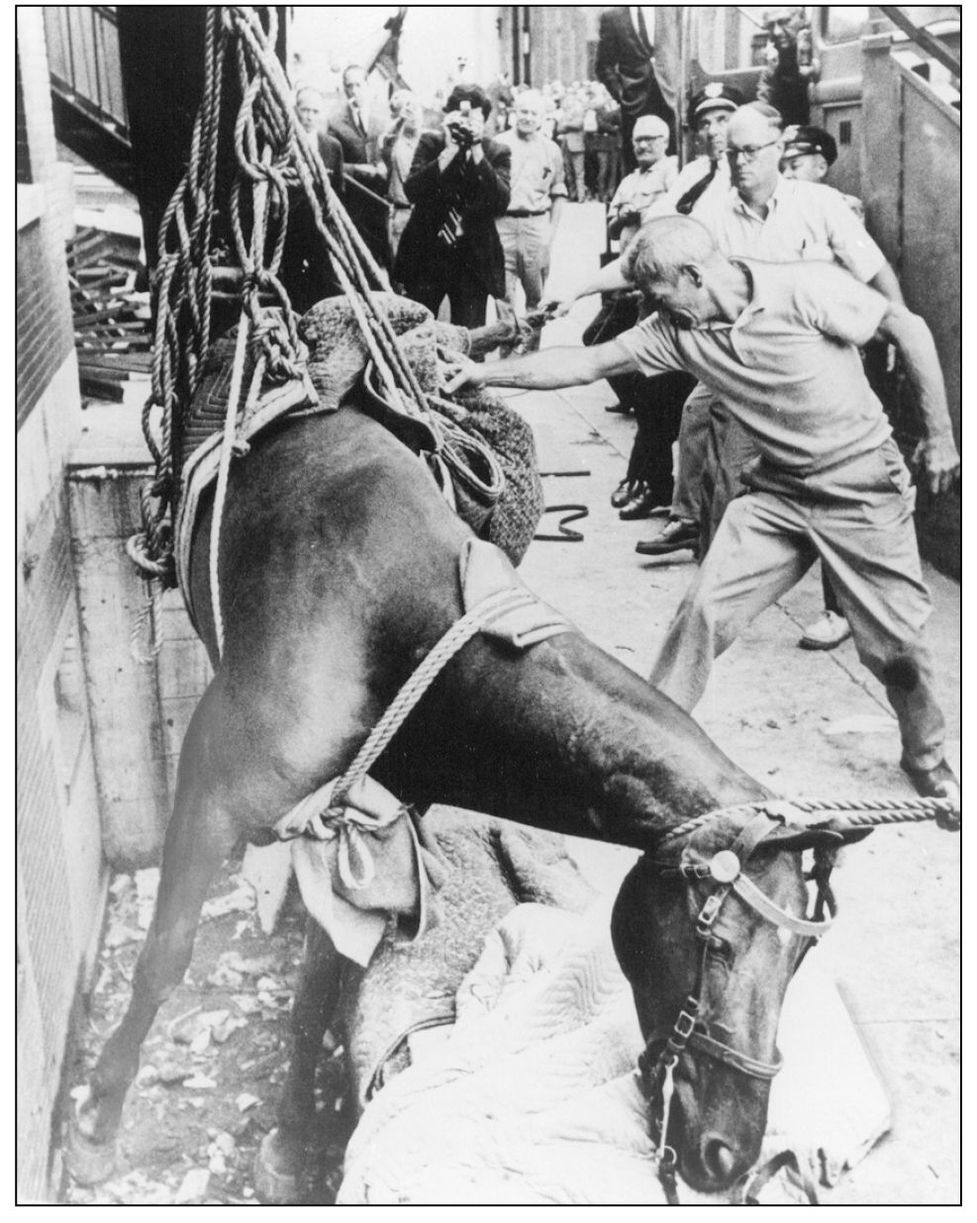

The hazards of patrolling an urban environment on horseback are many. Police horse “Tony” escaped from his tether and fell through a grate covering a window well on Euclid Avenue in 1969. The Mounted Unit veterinarian Dr. Dan Stearns (with glasses), Lieut. Ed Troyan, and Police Officer Carl Bultrowitz are evident in the background.

In a time before women were assigned to duty in zone cars, they wore these uniforms, as modeled by Elsie Bryant #437 and Elaine Newsome outside the Second District Headquarters on Fulton Avenue.

These women of the Cleveland Police Department are posing for the camera around 1967.

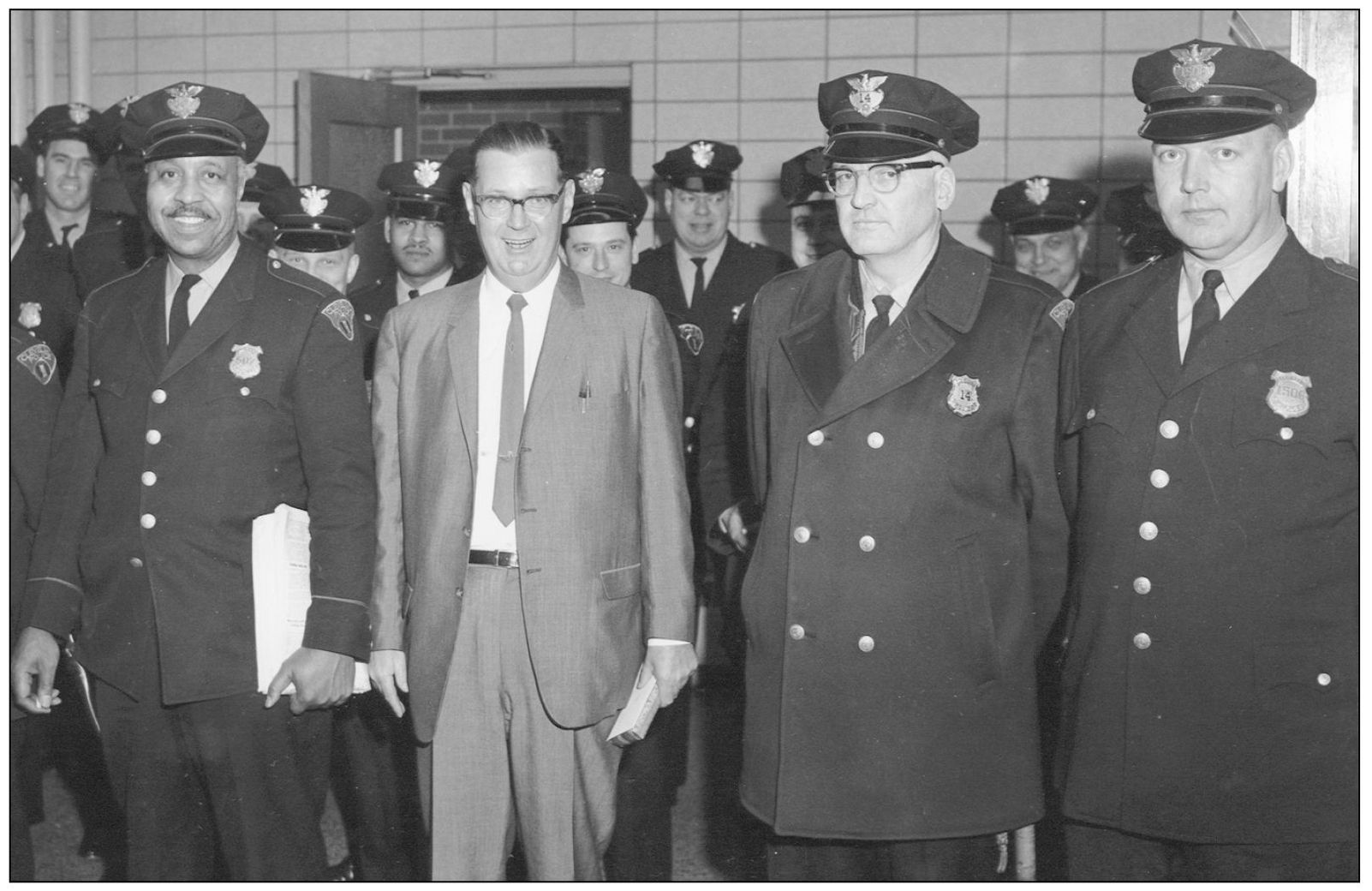

The officer on the left is Patrolman Edward Murray #507, a 32-year veteran of the Cleveland Police Department who was killed in the line of duty on July 2, 1975. Police Officer Murray is shown here with Safety Director McCormick, Police Officer John P. Gaughan #14, and Police Officer Edward P. Goggin #1506.

Capt. Jerome Poelking, the chief of detectives, presents retiring Det. Lee Peters his retirement plaque. Captain Poelking died in the line of duty in 1975. Standing behind Captain Poelking, in the plaid sport coat, is the future chief of police Edward Kovacic.

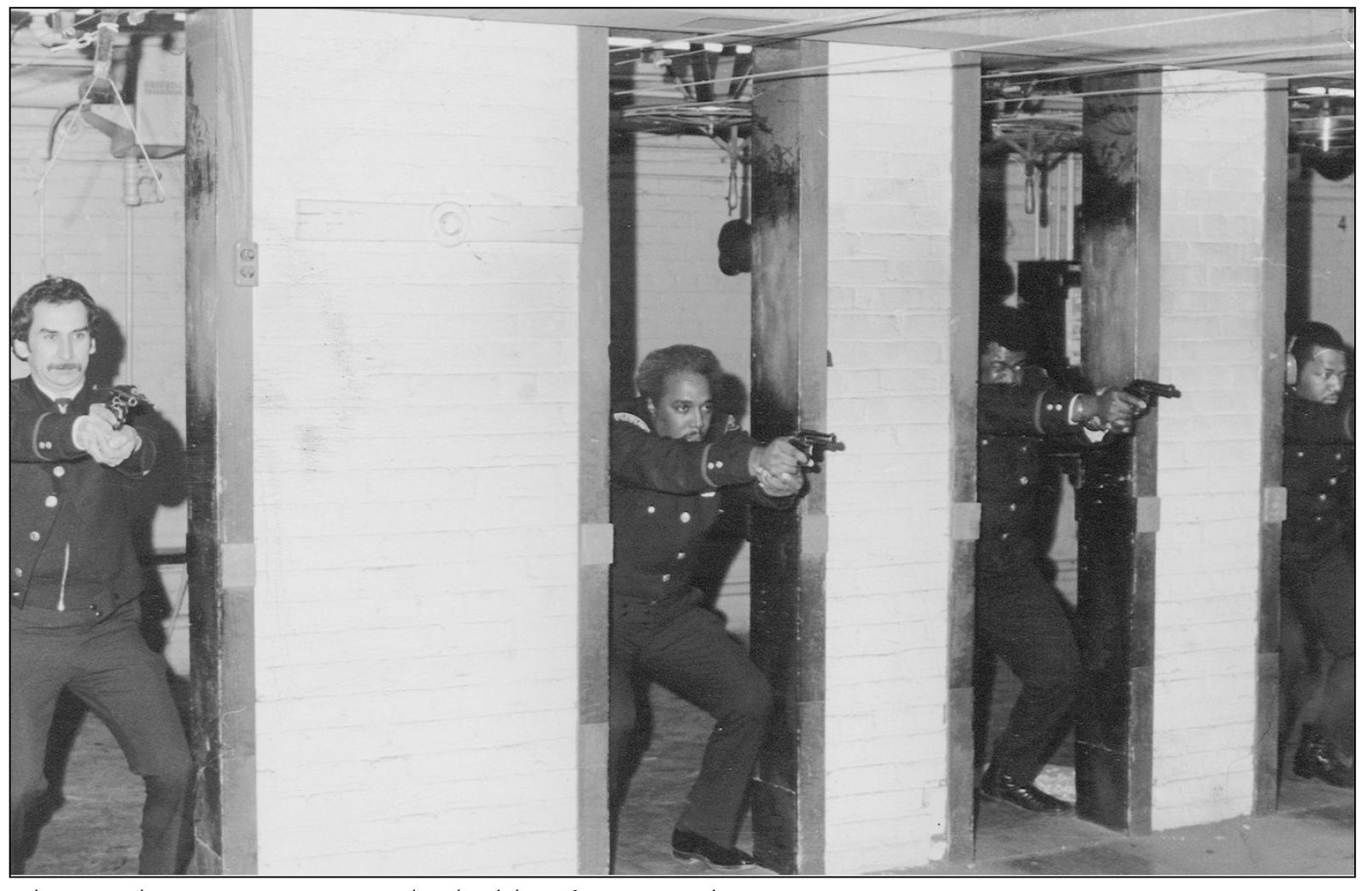

Members of the Cleveland Police Department are obligated to keep up their shooting skill and for years used the range at the historic Cleveland Gray’s Armory on Bolivar Road for training.

This is what target practice looks like if you are the target.

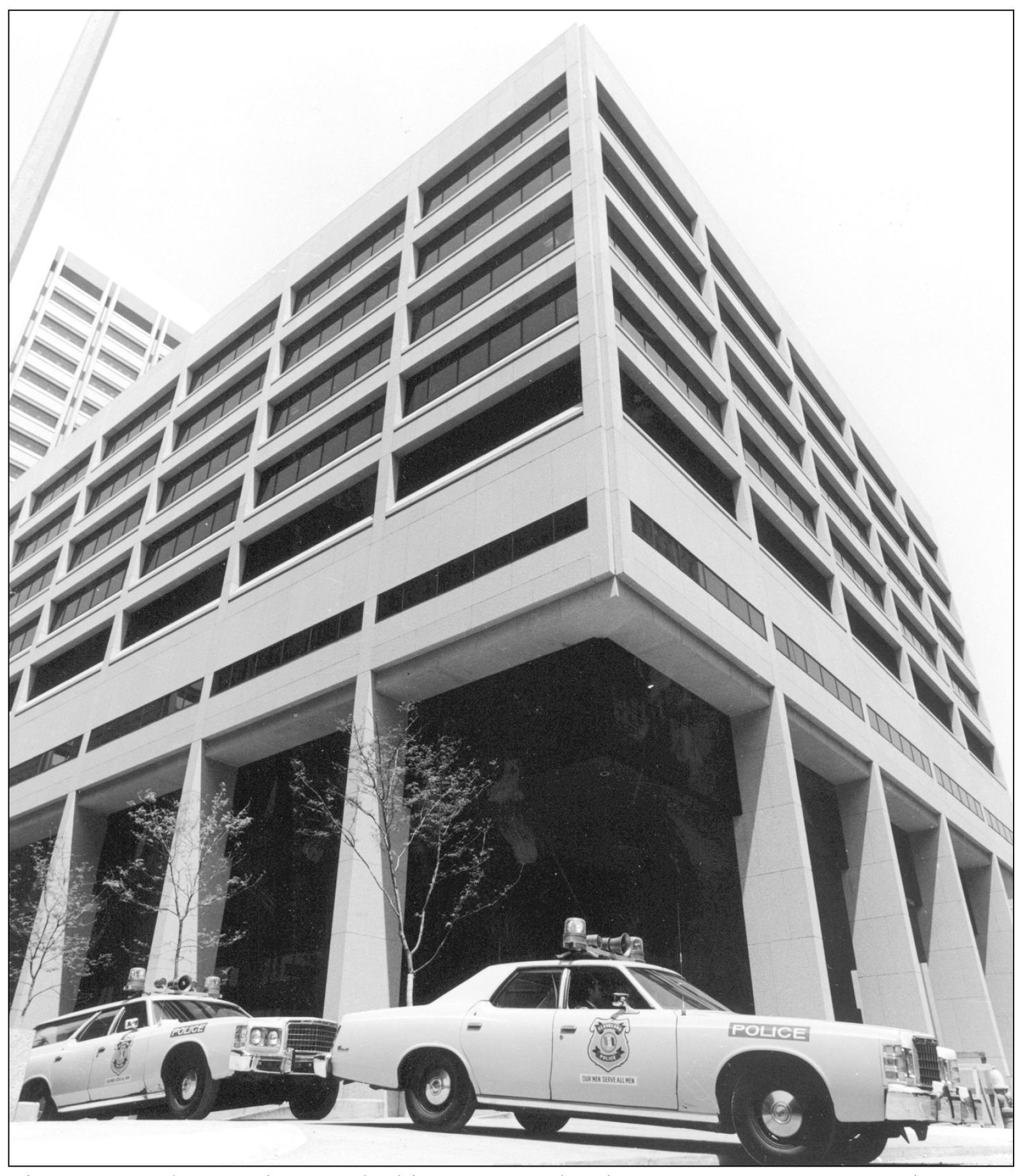

In the 1970s, Cleveland police zone cars were painted “safety green” and bore the motto “Our Men Serve All Men.” The color of the cars and the department’s motto were both short lived.

After the riots of the 1960s, the Cleveland Police Department made a strong effort to develop closer ties with the community they served as demonstrated by these officers “rapping” with some of the kids in their neighborhood.

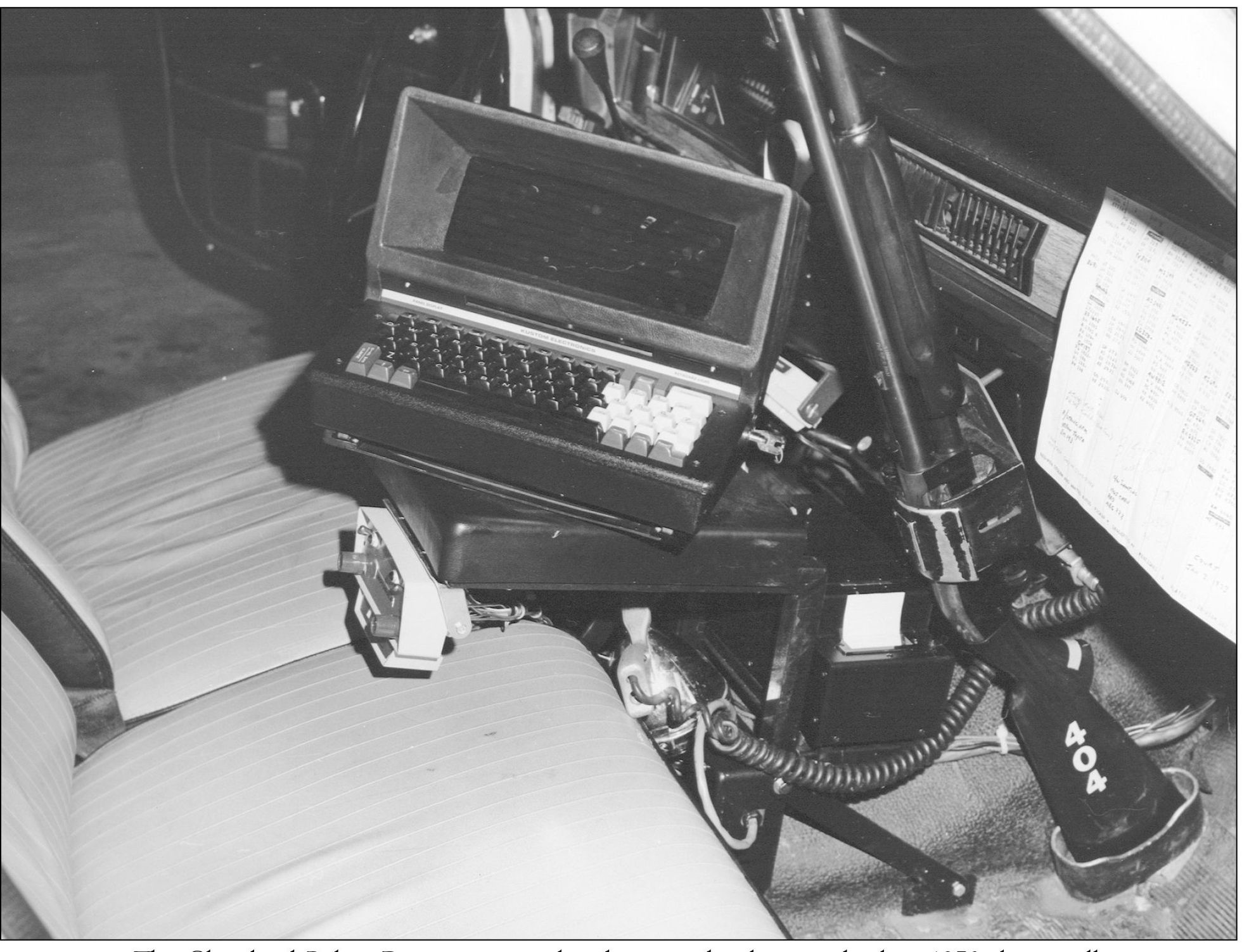

The Cleveland Police Department explored new technology in the late 1970s by installing computers in zone cars. The new computers were prone to numerous breakdowns and were not in use for long before it was realized that their dependability was not up to par. The piece of paper attached to the dashboard of the car is a “hot sheet”—a list of cars recently stolen in the city. Hot sheets are still used as a quick reference and back up to the computers now installed in all zone cars.

Although the Mounted Unit was always popular with the public, Patrol Officer Sam Reese #1712 performs one of the many functions suited to the mounted officer that is not necessarily popular.

Police Officer Michael Dugan #897 and Police Officer Jonathon McTier #1588 check crime clusters on a pin map at the Impact Task Force office in 1974.

The current Police Headquarters building was completed in 1973 as a component of the Justice Center complex in downtown Cleveland. The former headquarters building then became the Third District headquarters.

Patrol Officers Sharon Caine and Valerie Jones belie the slogan “Our Men Serve All Men.”

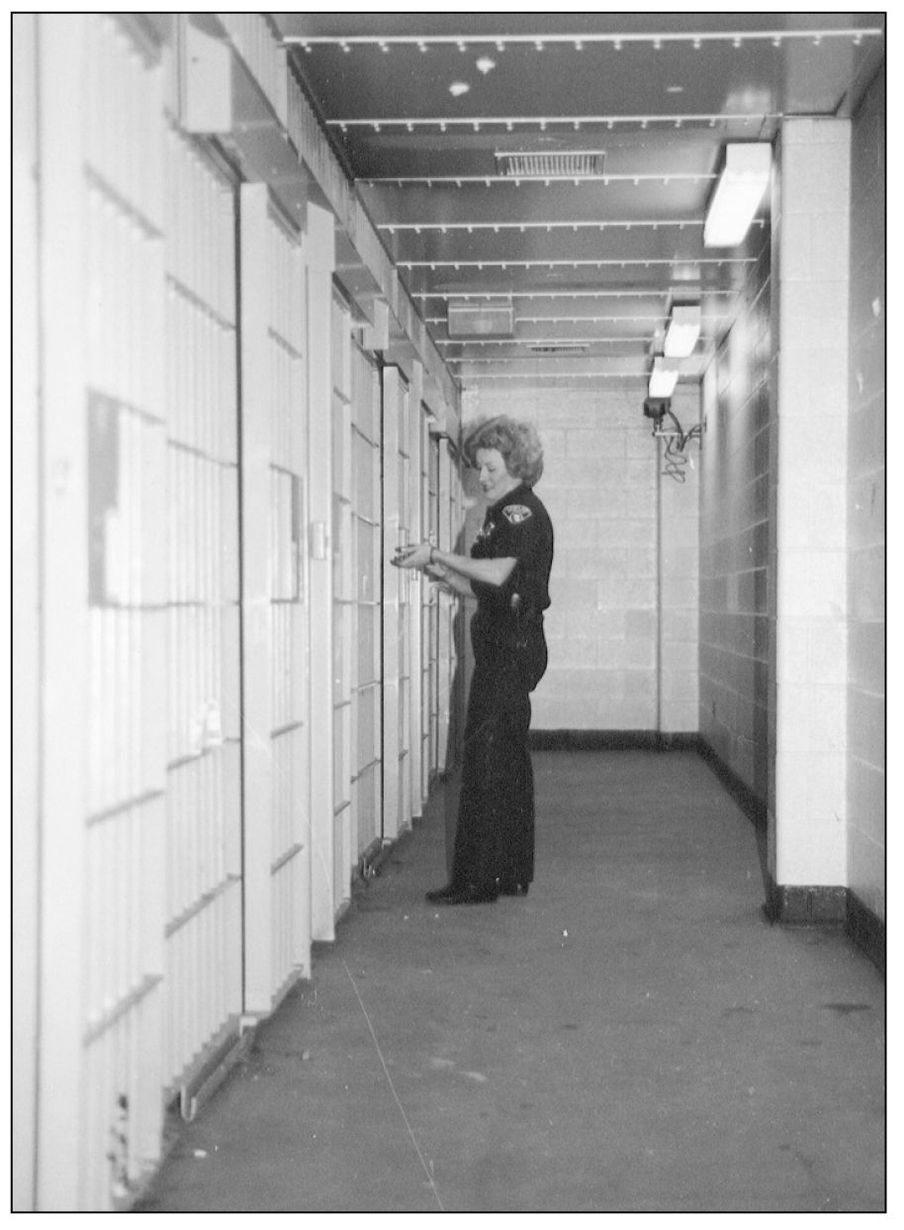

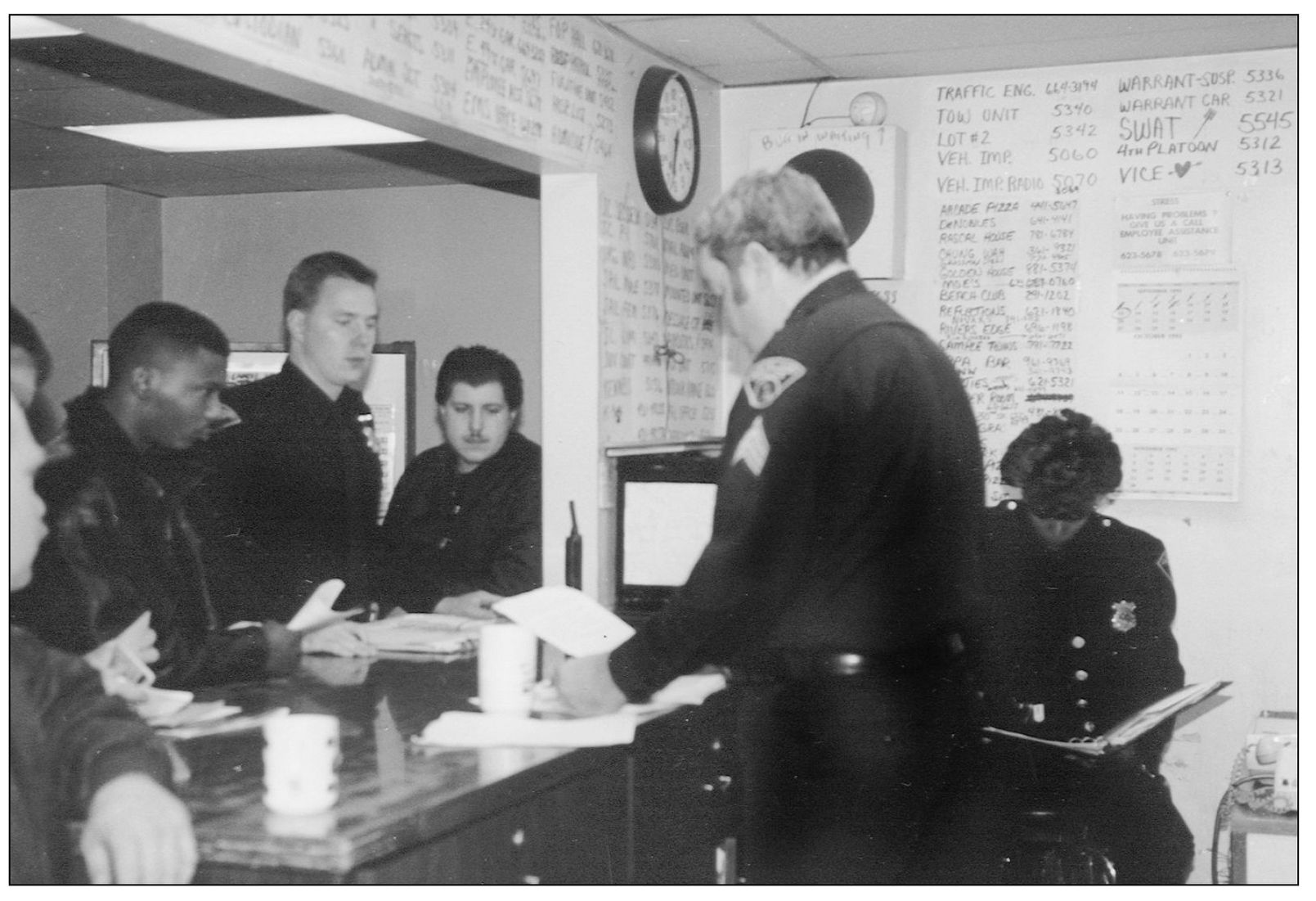

Except for the Third District, the Cleveland Police Department operates jails in each one of its district stations, as well as the Central Prison Unit in the Justice Center. In the 1990s, correctional officers, who are employees of the police department, replaced police officers assigned to the jails.

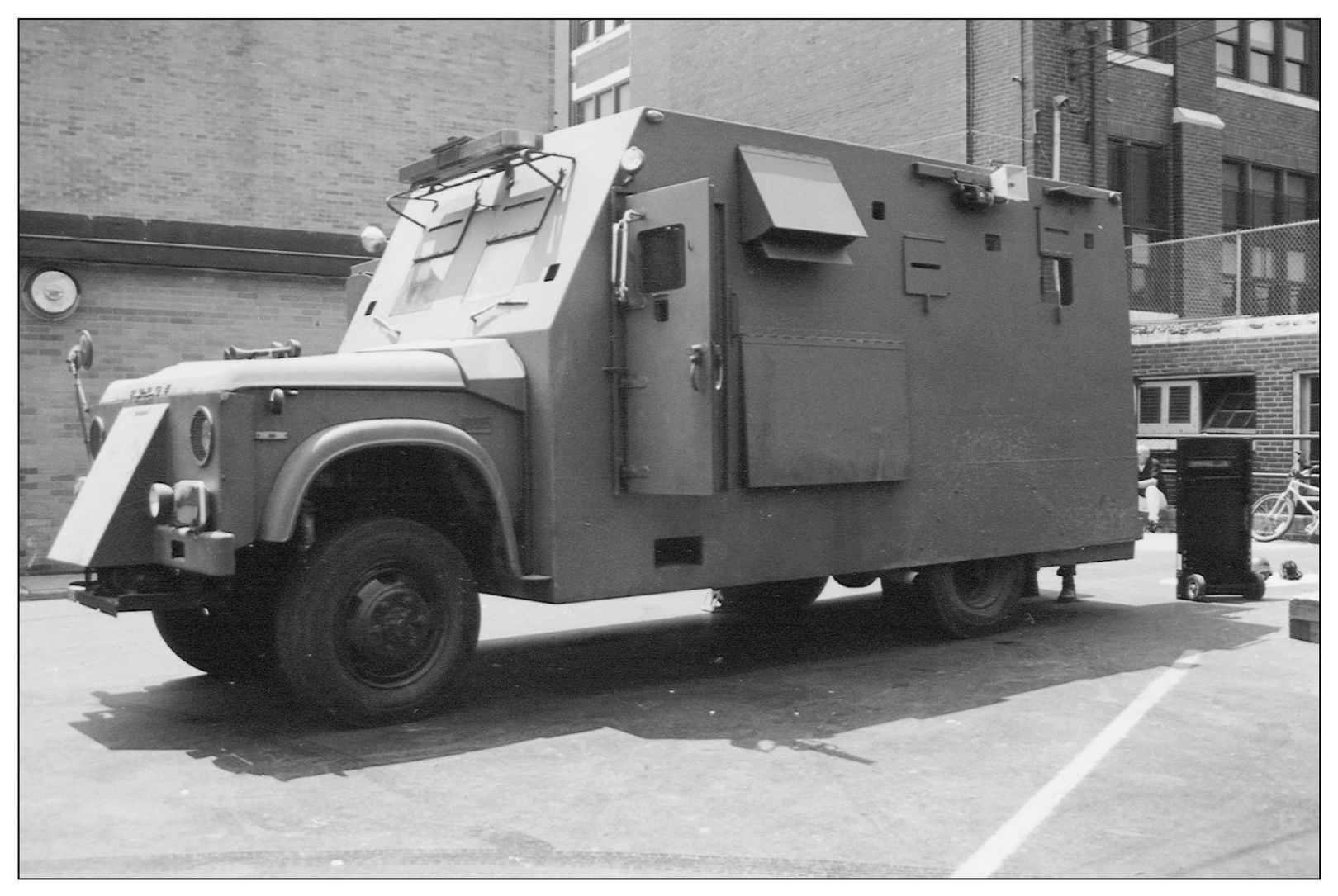

(above) “Mother” was the nickname of the SWAT Unit’s armored communication and rescue vehicle. Over the years, this vehicle has been a welcome sight to anyone, police or civilian, threatened by a suspect’s gunfire. Mother has been credited with saving dozens of lives and quelling many severely dangerous situations by its mere presence. In service since the early 1970s, Mother was recently retired and is now “assigned” to the Cleveland Police Historical Society.

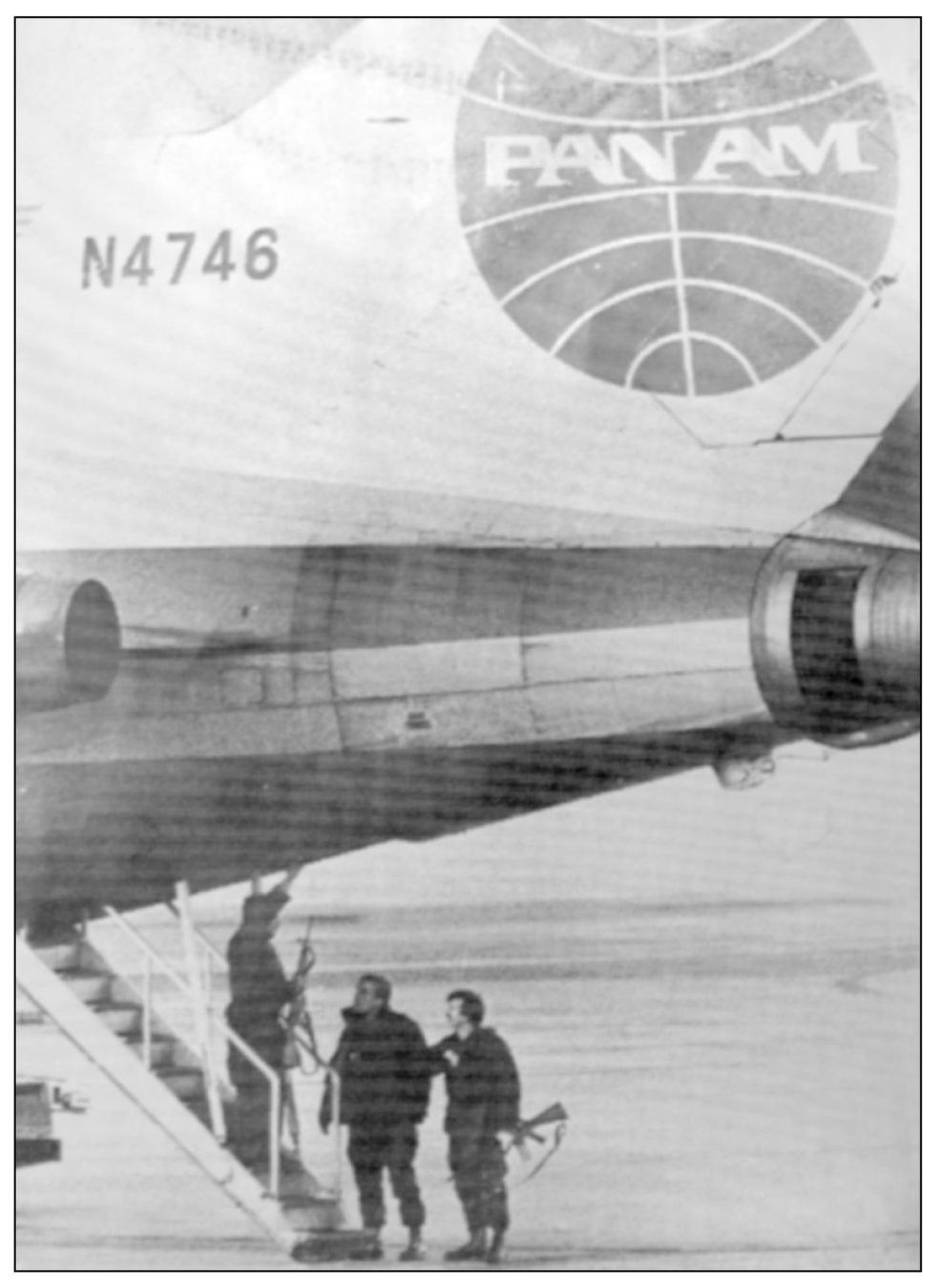

(left) On January 4, 1985, a mentally ill female wounded a Hopkins Airport ticket agent and attempted to hijack a jetliner. Four hostages were held. The decision to attempt a rescue was made, and the CPD SWAT Team boarded the plane. The hijacker fired off a shot at one of the officers, who was saved by his body amour. The hijacker was wounded and incapacitated, and the hostages were rescued unharmed.

The Jack F. Delaney, named in honor of the founder of the Ports and Harbors Unit, was the finest police boat on the Great Lakes when it was launched in 1985.

Cleveland police officers often arrive on the scene of fires or other medical emergencies before the Fire Department or EMS. Here, uniformed and plain clothes officers attend to the victim of a shooting—giving first aid and comfort and at the same time obtaining valuable information and evidence relating to the circumstances of the incident.

The Cleveland Police Department finally patrolled the city by land, sea, and air when the Aviation Unit was activated on January 2, 1990, comprised of two Schweitzer 300C helicopters and six officers.

The “old ways” met the “new ways” in this manhunt for a criminal suspect.

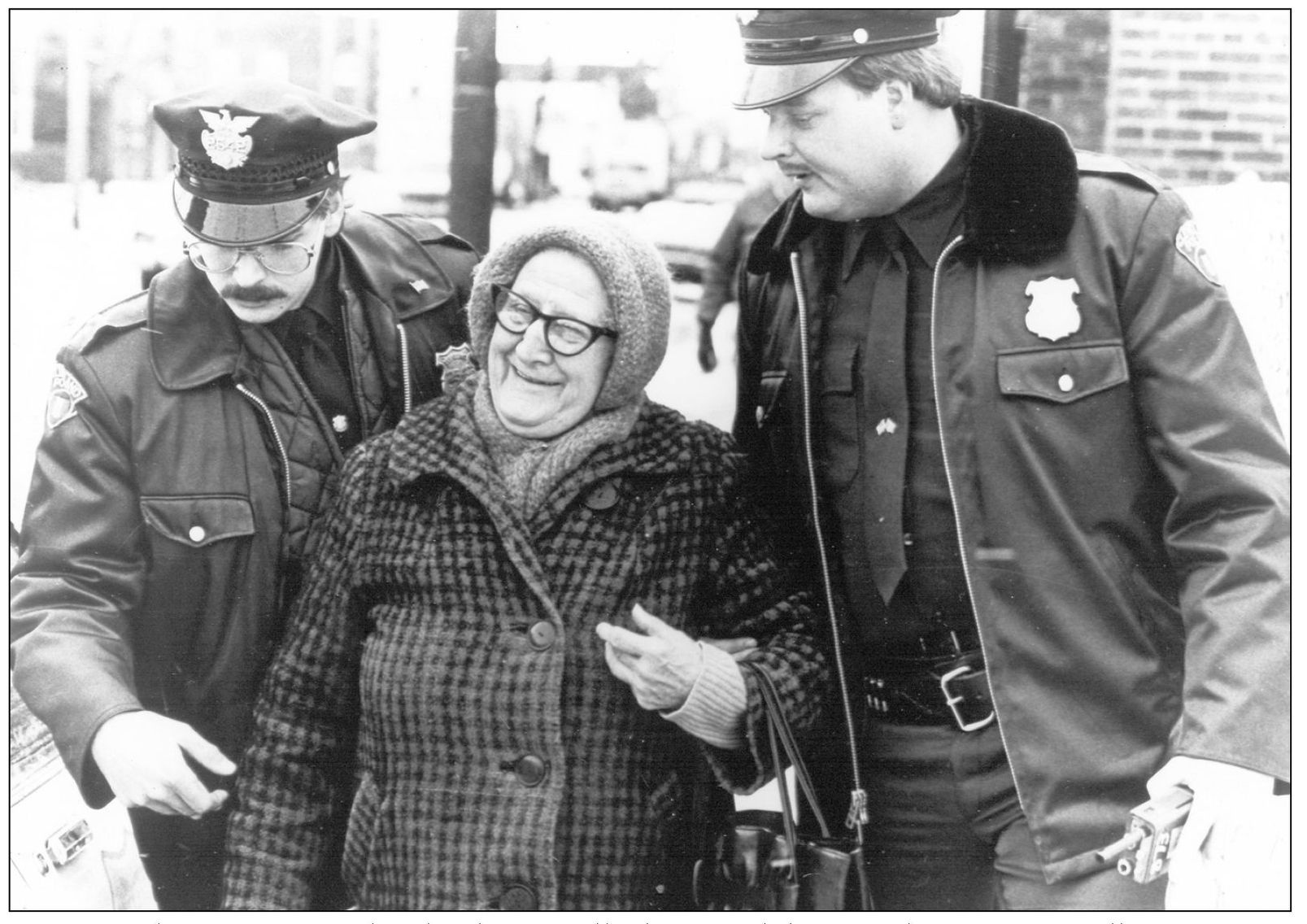

Being a police officer in Cleveland is not all “down and dirty.” Police Officer William Wagner #2542 and Police Officer Patrick Evans take time to do what being a police officer is all about, helping people.

For as long as anyone can remember, the Cleveland Police Department has maintained a holiday tradition of raising money to provide food baskets to needy families in their respective districts.

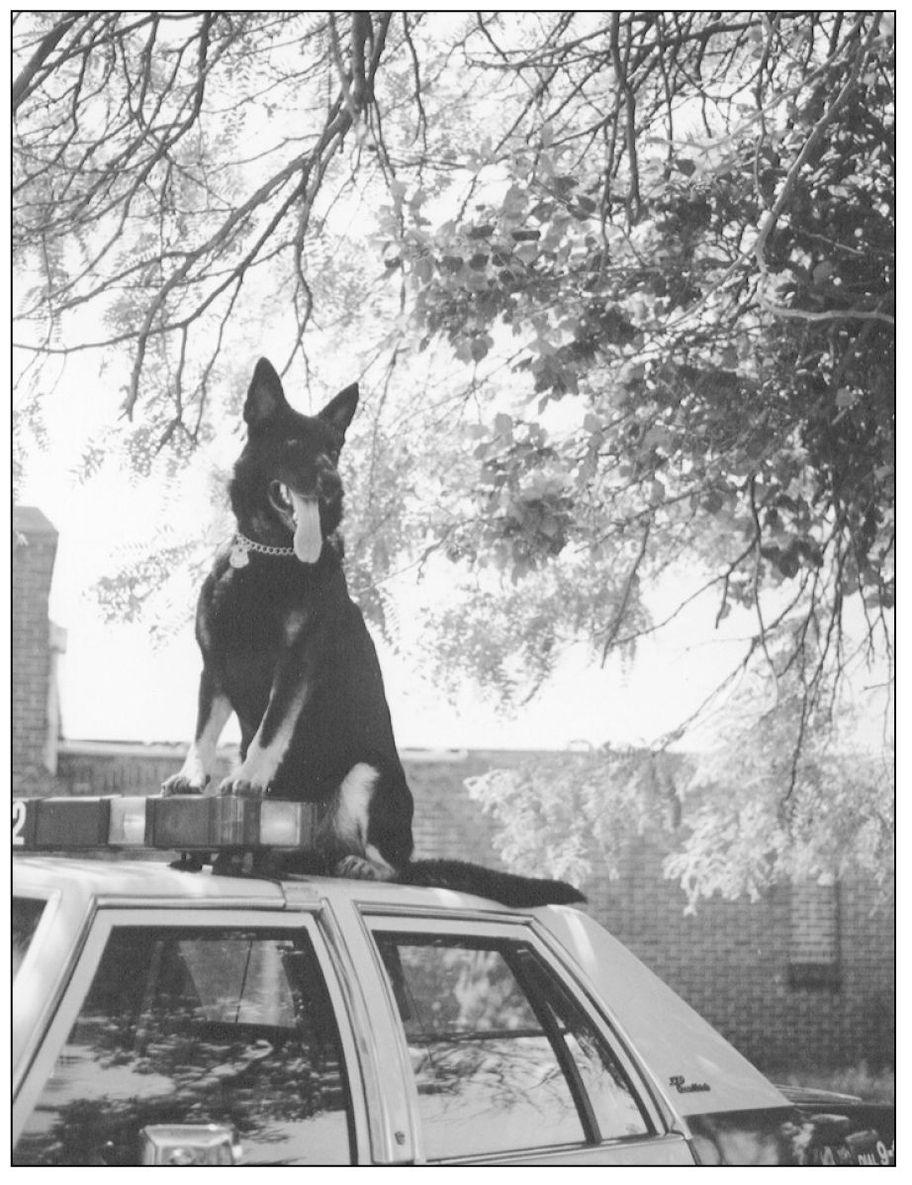

The Cleveland Police Department established a K-9 Unit in 1989 with dogs that specialized in bomb detection, tracking, drug detection, and general utility.

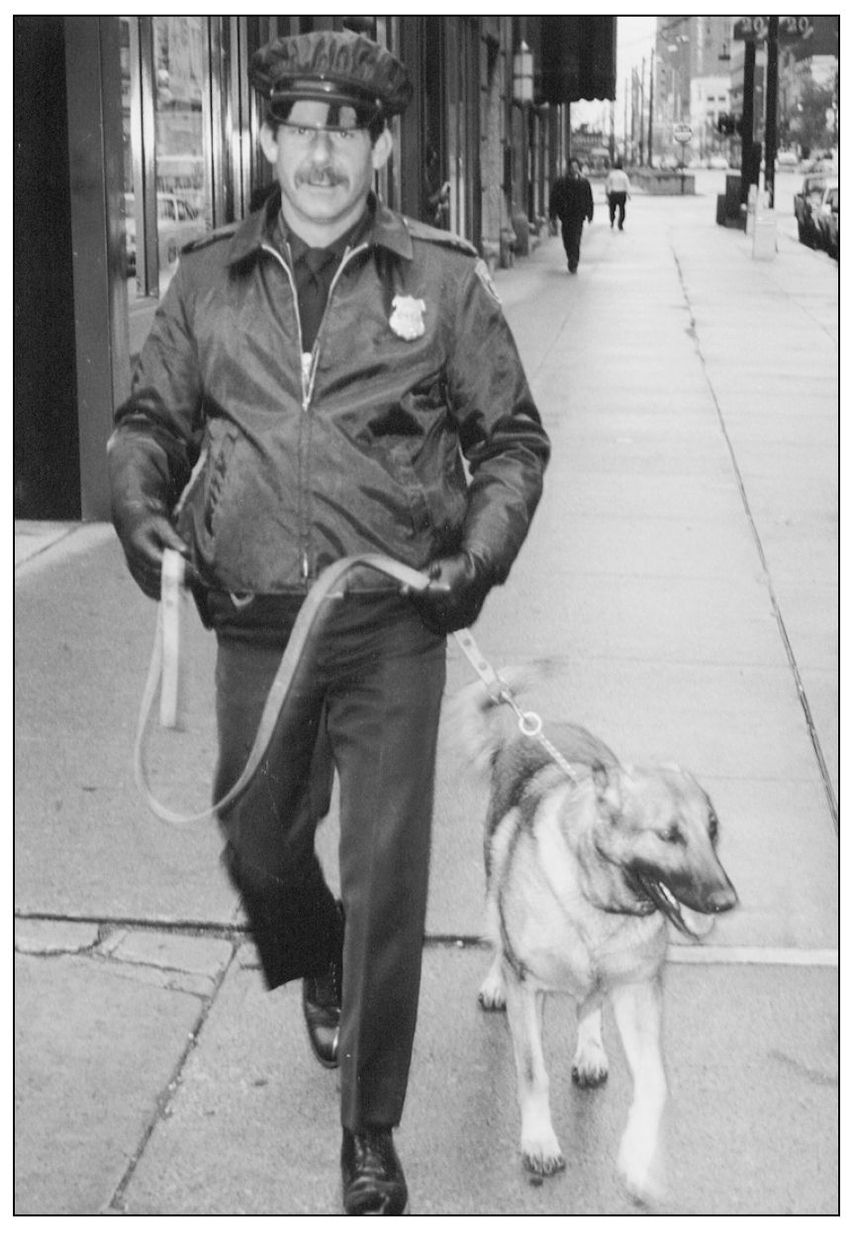

Police Officer Bob Patton #2469 and his partner Oden, working the downtown safety patrol beat.

At the beginning of each shift, officers attend roll call to insure that they all have the proper uniform and equipment; receive their daily assignment, and any special information that needs to be passed along—such as areas of special attention and recent crimes.

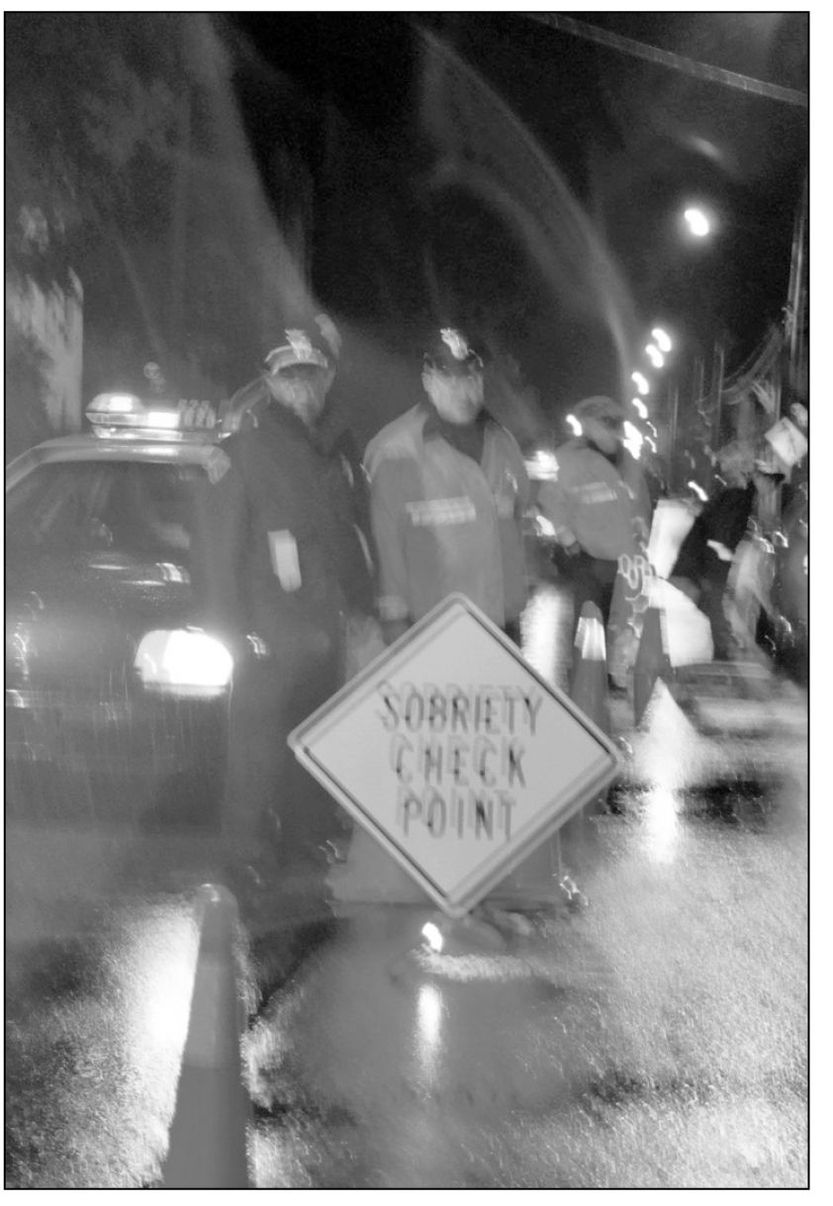

In the 1990s, sobriety checkpoints became a law enforcement fad as a tool to combat the drunken driving problem. Even today, if you approach a DUI checkpoint and see this image in this manner, you may be in trouble.

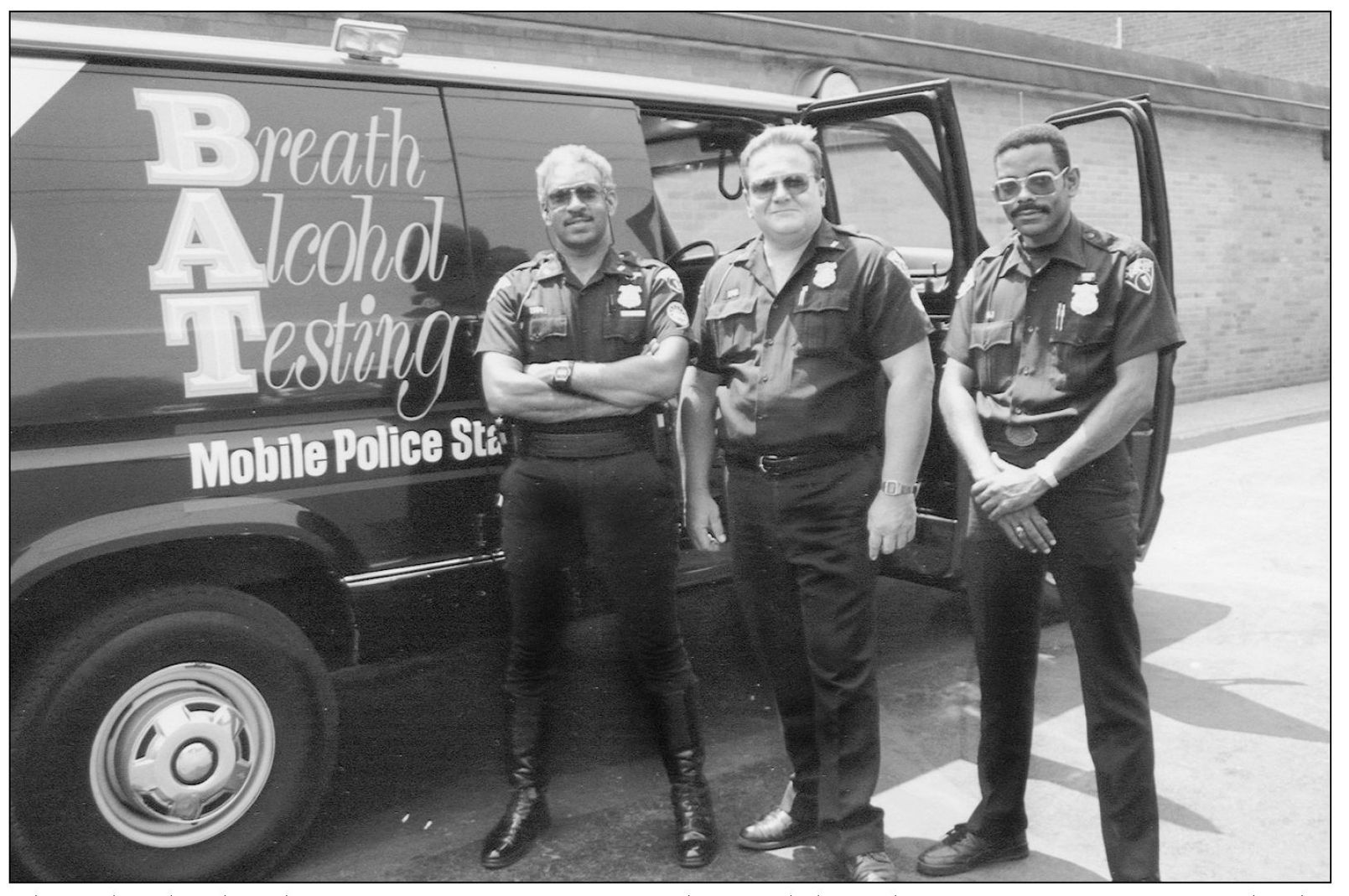

The Cleveland Police Traffic Unit operates this mobile police station to assist with the enforcement of the DUI laws. The Breath Alcohol Testing Mobile Unit, or “BAT Mobile,” is equipped to test, book, and hold drivers suspected of alcohol related offenses.

This group of suspects has been placed under the control of this officer during the “bust” of a known drug house.

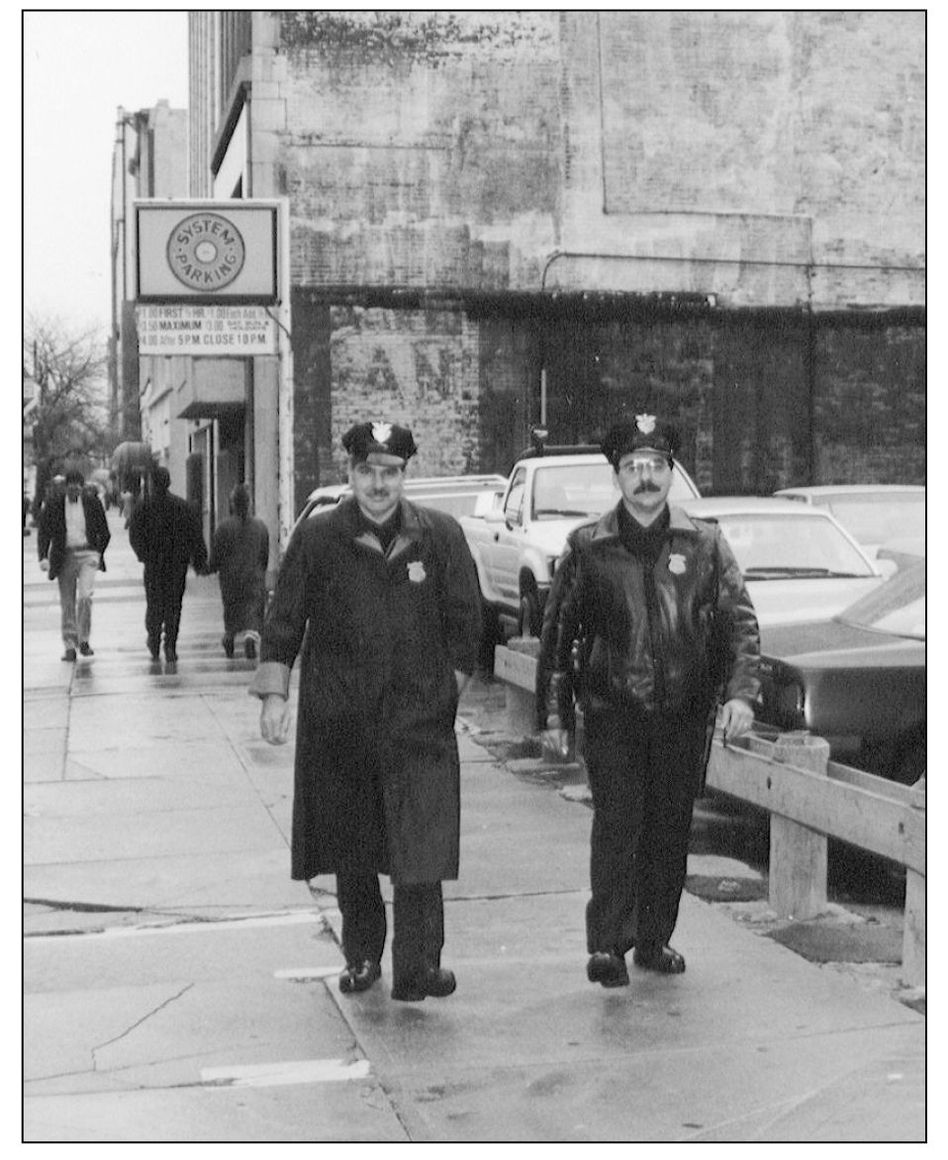

Law enforcement personnel, from the constables of the early 1800s and members of the city’s night watch in the mid-19th century, to today’s deputy marshals and police officers have patrolled the city streets on foot. PoliceOfficerGeorgeSchultz#2243and Police Officer Nicholas Moutsus #868 “walk the beat” in the Playhouse Square area.

Police Officer Don Williams #1222 and Police Officer Brian Fischer #1349 patrol the city’s Third District.

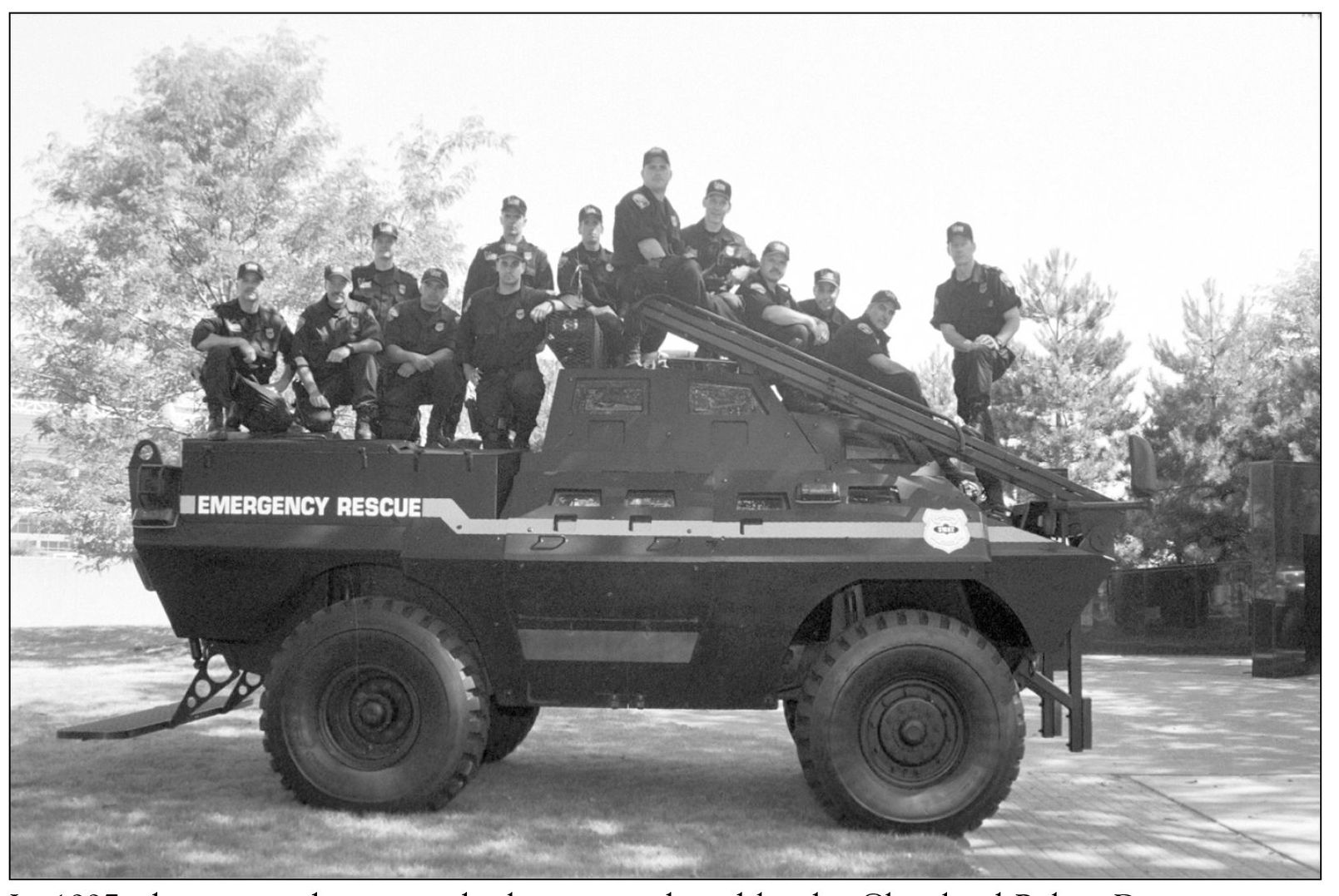

In 1997, this armored rescue vehicle was purchased by the Cleveland Police Department to replace its ailing and aged predecessor. Known as “Mother II,” it is deployed during high-risk situations—as well as community events, where the citizens of Cleveland warmly receive it.

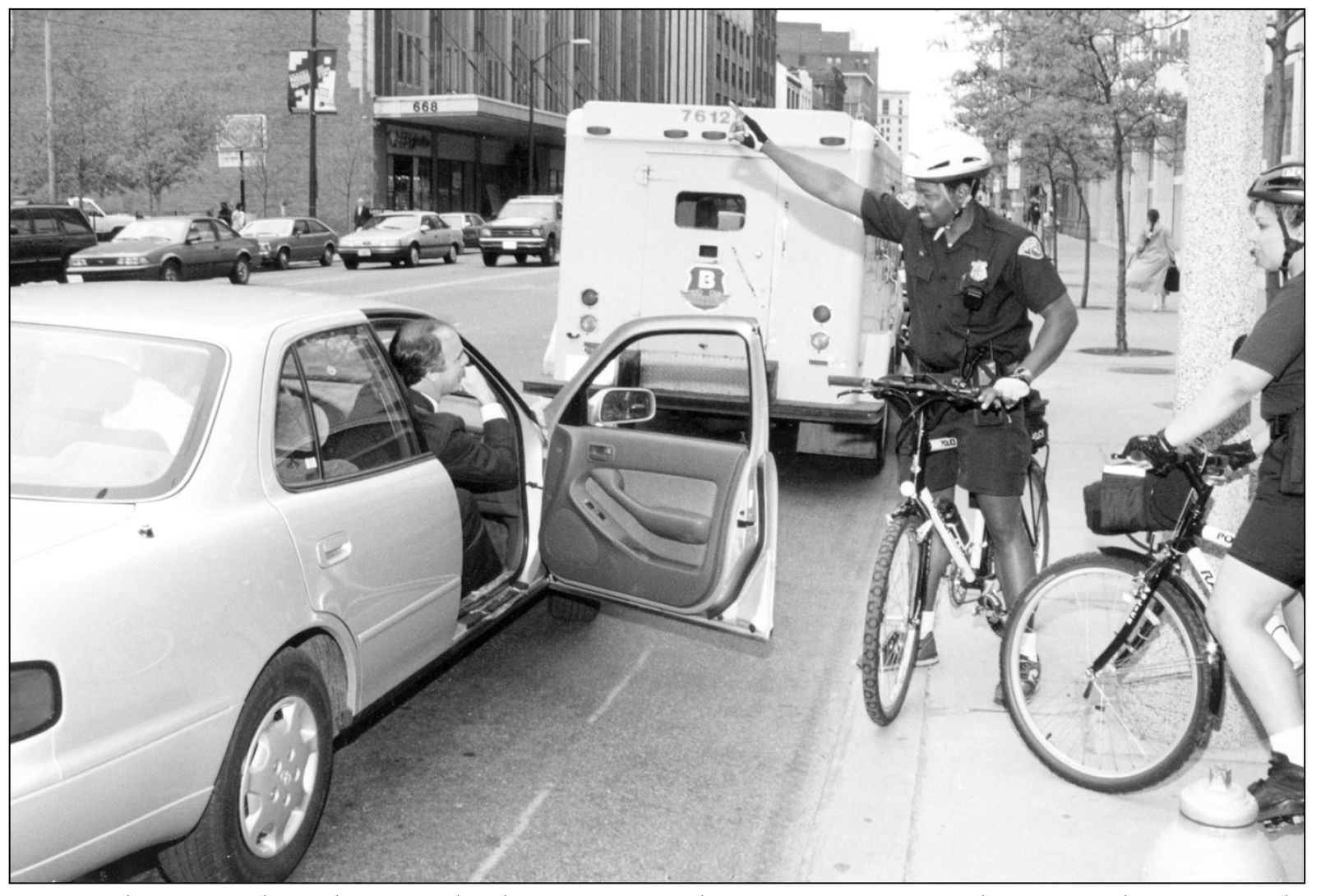

During the 1990s, bicycles came back into use as a law enforcement tool after an absence nearly 75 years. The bicycle officer was seen as a community relations tool, removing officers from the insulation of the zone car and making them more accessible to the public.

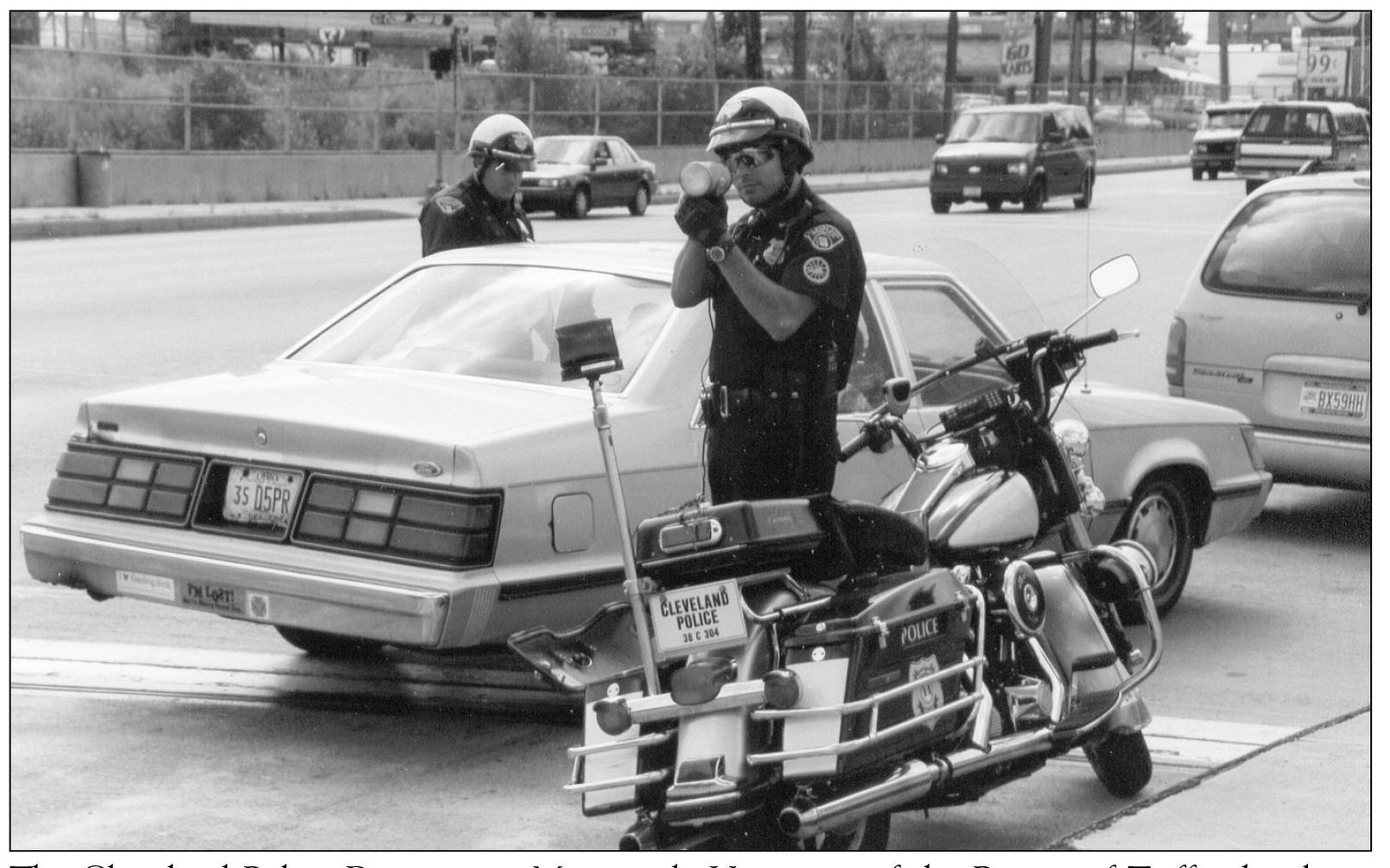

The Cleveland Police Department Motorcycle Unit, part of the Bureau of Traffic, has been and continues to be an invaluable asset in the department’s mission to insure traffic safety. With the use of a portable radar gun, these motorcycle officers are able to monitor the speed of approaching traffic.

The Cleveland Police Department operates a police station inside Hopkins International Airport. Prior to 9/11, officers assigned to the Hopkins Airport Unit provided security patrols, assisted with traffic control, and were available to travelers to handle reports of crimes, give directions, and answer questions. Their mission has taken on an entirely different tone in these post 9/11 days, when airport security has become a nationwide focus.

In the early 2000s, the Aviation Unit replaced their aging Schweitzers with two MD 500e helicopters equipped with half-million candlepower searchlights and FLIR (Forward Looking Infrared) for nighttime surveillance.

The Pipes and Drums of the Cleveland Police, established in 1996, is seen here during a St. Patrick’s Day parade, c. 2000.

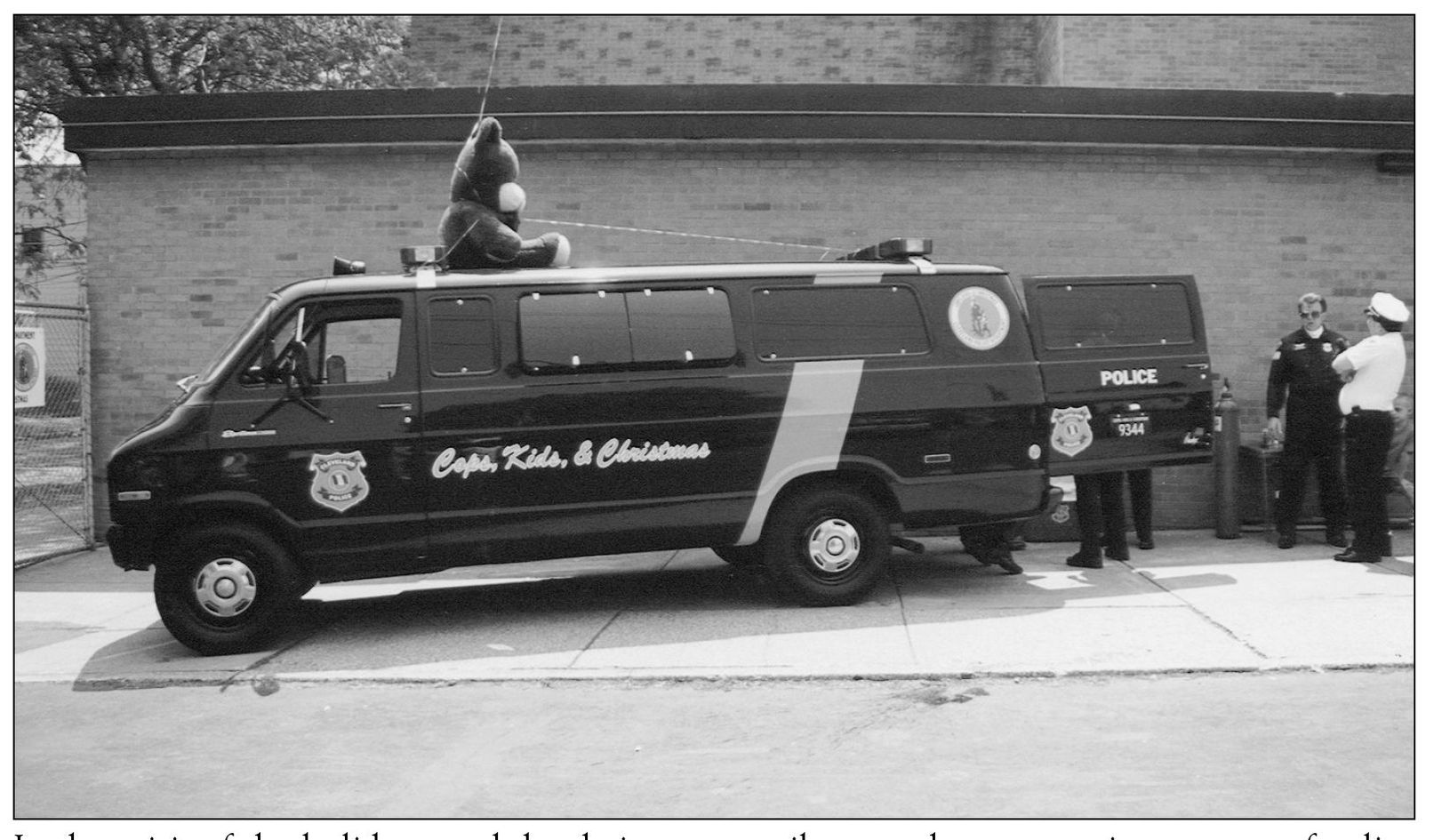

In the spirit of the holidays, and the desire to contribute to the community, a group of police officers led by Capt. Joseph Sadie (far right) created the Cops, Kids and Christmas program. They distributed toys and candy throughout the city during the Christmas season. The program was recently expanded, and the name changed to simply Cops and Kids, in order to reflect a now year-round effort to accomplish its goals.

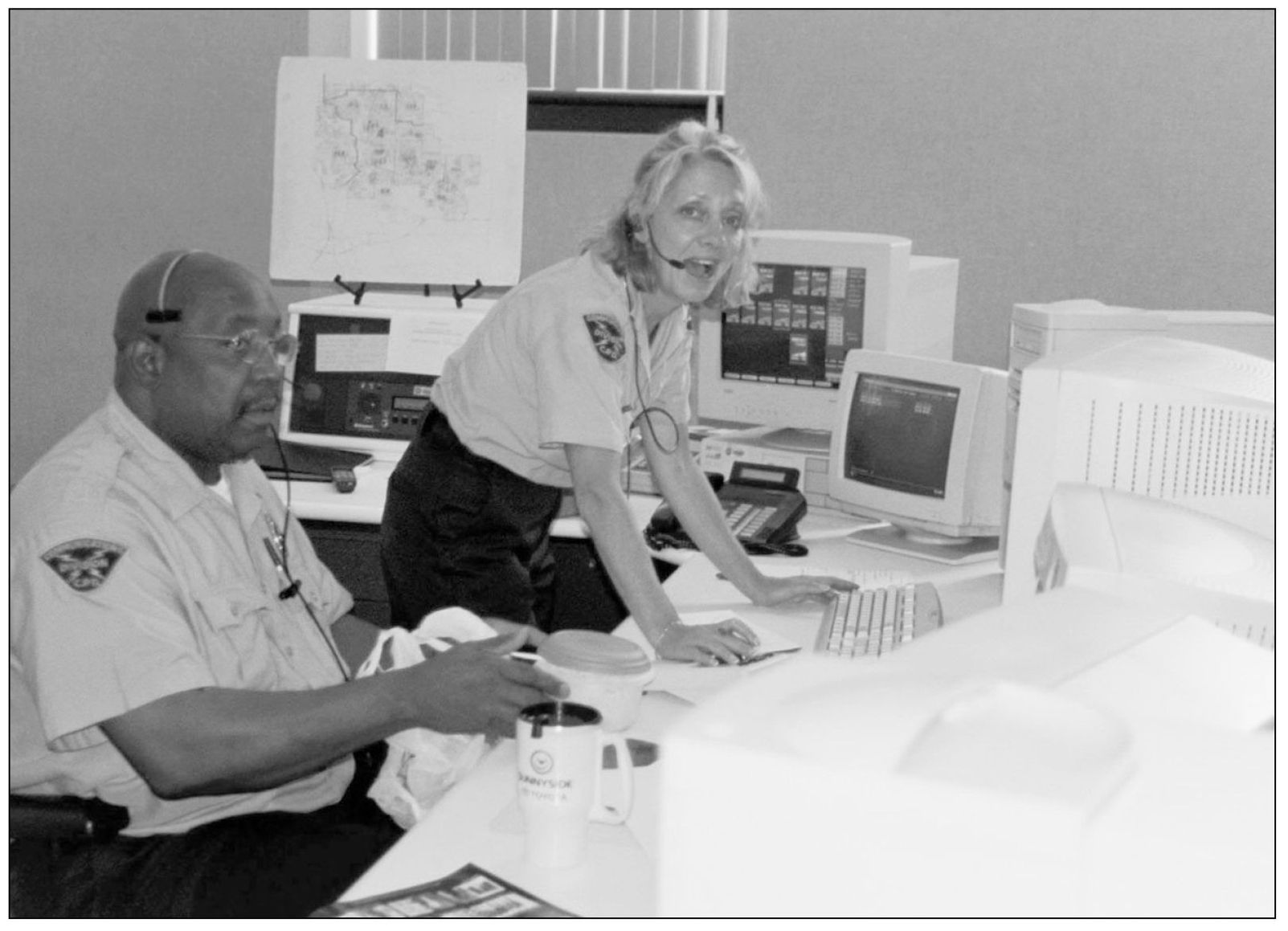

Communications is possibly the most important tool in the modern police department’s arsenal. The CPD Communications Unit recently moved into a modern, computer-aided dispatch center, which it shares with EMS and the fire department. Hundreds of thousands of calls for service are received and handled each year.

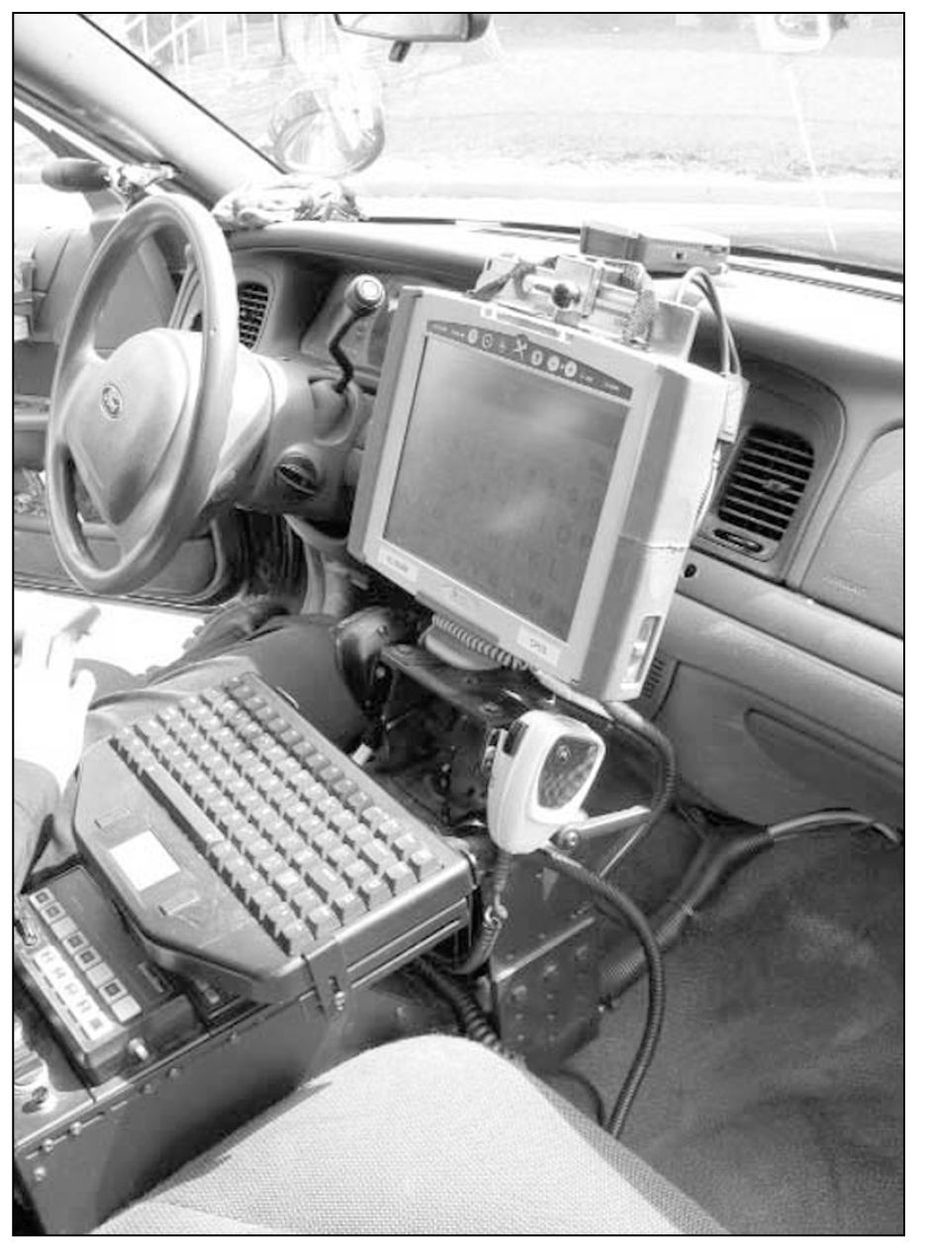

On October 30, 2002, after an absence of almost 25 years, 28 computers were installed in Fourth District zone cars that were participating in the “Mobile Data Terminal Computer Pilot Project.” By 2004, all CPD zone cars were equipped with these mobile data terminals.

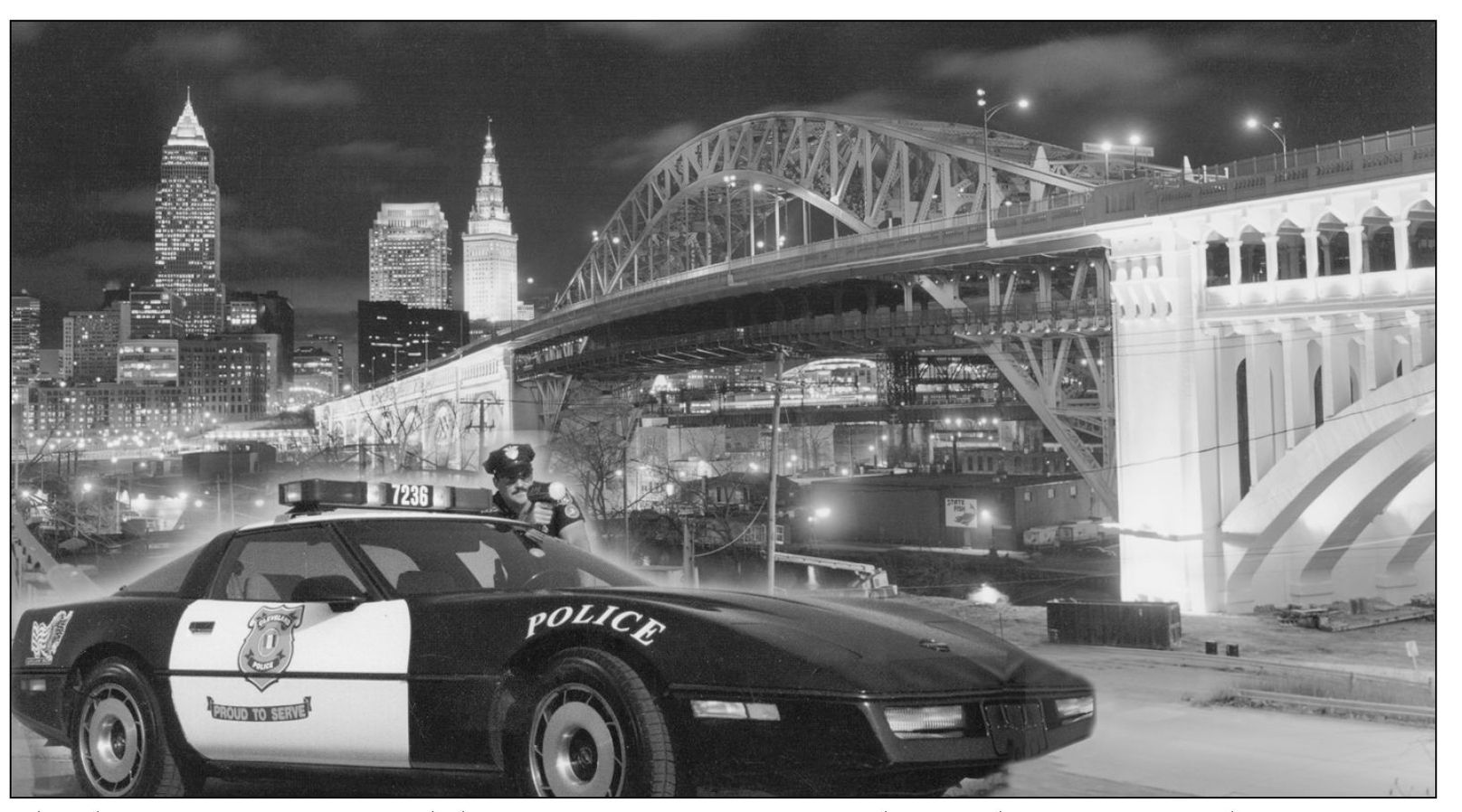

The department confiscated this corvette after it was used to facilitate a criminal enterprise. It was cleaned up, painted black and white, and equipped with police radios so it could be used as a traffic enforcement car and community relations tool.

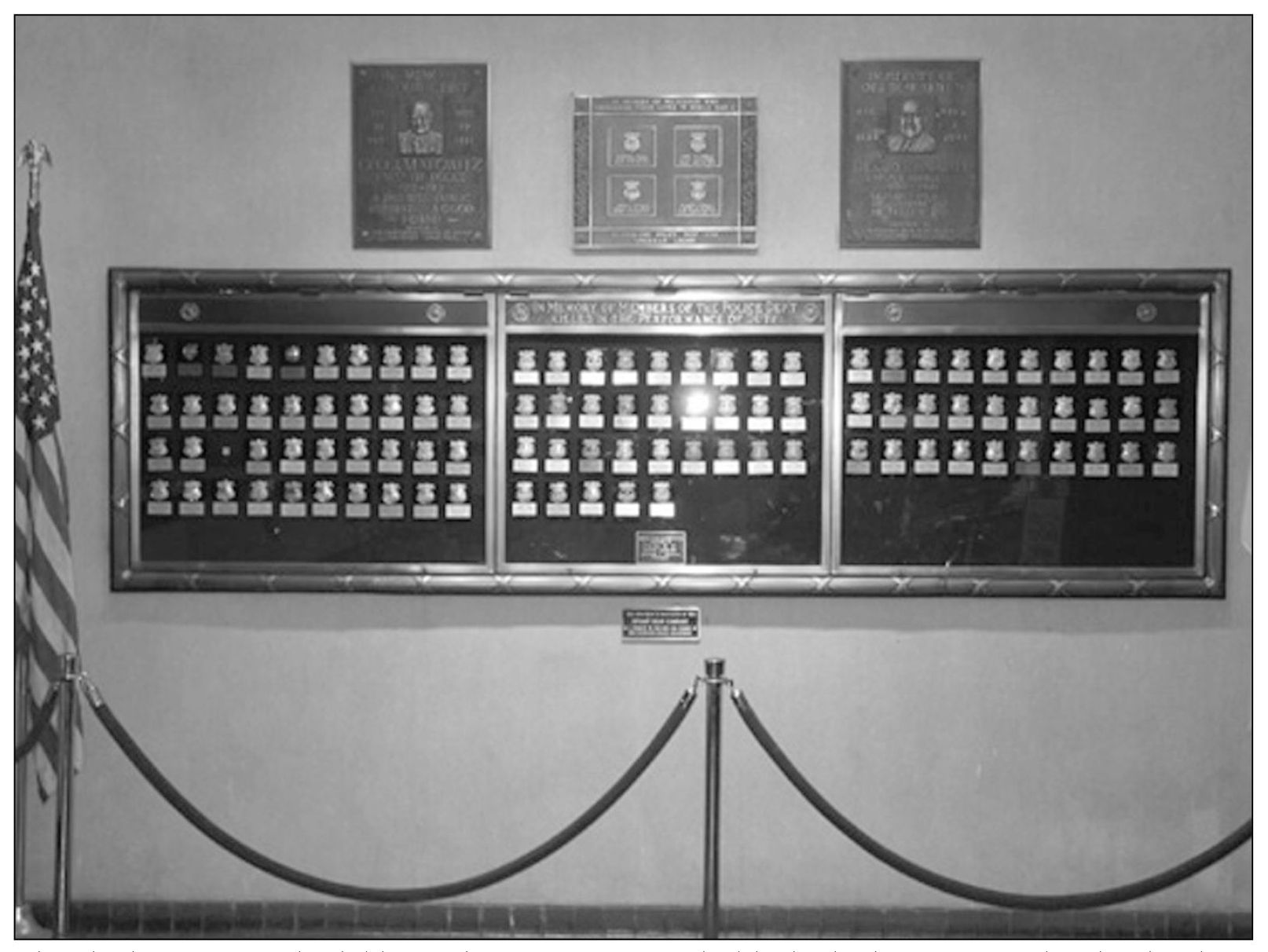

The “badge case” in the lobby of the Justice Center holds the badges of 106 Cleveland Police Officers that have died in the line of duty. When a Cleveland police officer falls, his badge is retired—never to be issued again. It is displayed with honor to remind us all of his sacrifice.

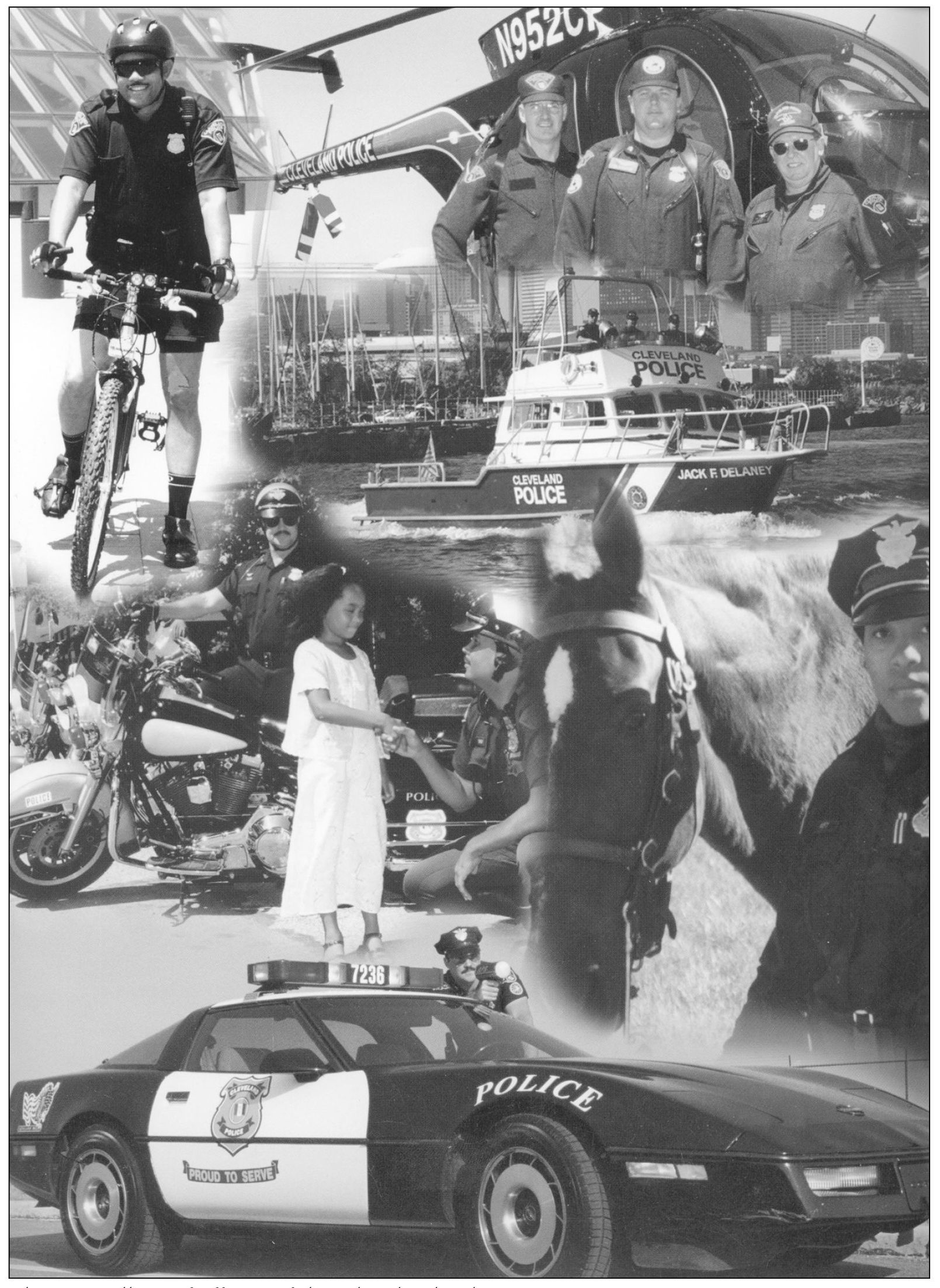

This is a collage of officers of the Cleveland Police Department, c. 2001.