Proof I’m Probably Going Crazy Like Mom

I look like Mom, so I probably have more of her genes than Dad’s.

I say stupid stuff when I don’t want to.

I make a lot of people mad, and sometimes not on purpose.

I am willful. Just ask Peavine’s mom and my teachers.

I saw things at the Abrams farm that weren’t real.

Proof I’m Probably Not Going Crazy Like Mom

Just because you look like a sick person doesn’t mean you’ll get sick.

Angel says stupider things than me, lots of times.

Some people need to get mad. Maybe I’m helping them talk about their problems.

“Willful” is another word for “determined,” and “determined” sounds a lot better.

Maybe the Abrams farm is haunted and I saw ghosts.

I snuggled into Dad in his recliner and tried not to think about the Crazy List lying on my desk in my bedroom, or Crazy Mom, a quadrillion miles away in Memphis, locked away in the hospital again. The other kind of hospital.

We had the lights off, and we were supposed to be settling down for bed. Dad was big on early bedtimes when he had to run the show. He pulled up my Superman blanket until it covered my shoulders, then flicked on the DVR and punched the local news. It droned in the background. I yawned and stretched.

“Careful, there.” Dad kissed the top of my head. “This old chair won’t hold us both forever.”

I put my face in Dad’s chest and burped applesauce and hamburgers. The applesauce was because it counted as fruits or vegetables, and Dad tried to keep us healthy, at least a little bit. Plus, if Mom got home from the hospital and found out we had eaten nothing but junk food while she was gone, she’d throw a total fit.

Dad smelled like pine needles and his blue cotton pajamas. That sort of made me relax and sort of didn’t, and the news talked about rain or not rain, and I said, “I miss her already.”

“I do too.” Dad kept his eyes on the news when I glanced up at him. TV shadows played and flickered across his face, but I could tell he was frowning.

“Are you going to look sad the whole time she’s gone this time?” I poked his chin with my fingertip.

“I don’t know.” He crossed his eyes as he looked down at me. “Are you?”

“Probably.”

“Okay, then. We’ll look sad together.”

He uncrossed his eyes and went back to paying attention to the news, which had moved on to sports, which was even more boring than bake sales and weather.

I sighed. “Good dads would try to cheer up their daughters and pretend everything was going to be perfect.”

“Good dads tell the truth and face it with their daughters.” He put his hand on my head and stroked my hair. That usually made me sleepy, but tonight it just made me sigh all over again.

“So, what’s the truth about Mom?” I asked him.

A few seconds went by before he answered. “The truth about Adele is, she’ll come back to us as soon as she’s able. And the truth about us is, we’ll be waiting.”

I picked at the corner of my blanket and didn’t say anything. That was what I had wanted to hear, so why didn’t it make me feel any better?

“Are you and Peavine still investigating the Abrams fire, Footer?”

“Since we’re talking about truth and everything, I guess I have to tell it, so yes, sir.”

It was Dad’s turn to sigh. I rose up and down as his chest heaved, then heard the rumble of his voice through his chest as he said, “You know I don’t want you to do that. I don’t think you should spend your energy on sad, terrible things.”

“It keeps my mind off other sad, terrible things.”

I went up and down again as Dad took a really deep breath. He rubbed my hair some more as he said, “Okay. But if I tell you to stop, I’ll mean it.”

“Yes, sir.”

I wished I could get sleepy, but I just pretended. I had to do that when Mom was gone, because I didn’t sleep much, but if Dad found out I was awake, he’d try to stay up with me. Then he’d get all tired and grumpy and I’d feel guilty.

So I pretended until he carried me to bed and tucked me in. Then I waited until I heard his door close, and waited a little longer, until I saw his light click off and the hallway go dark. Then I got up and pushed my own door closed, snuck back across my bedroom, turned on my little desk lamp, picked up my Crazy List, and opened up my laptop.

One by one, I picked out the items on the list and did some searches. Okay, okay. Ghosts at the Abrams farm were probably a stretch. But I looked up everything I could find on hallucinations, and I didn’t think I was hallucinating when I saw all that stuff.

Wikipedia said, “A hallucination is a perception in the absence of apparent stimulus that has qualities of real perception.”

Huh? Did Angel write definitions for these people?

The rest of the article explained that hallucinations could come from seizures and infections and drugs and falling asleep when you thought you were awake and migraines and staying in dark rooms too long and brain tumors. I rubbed the sides of my head. Brain tumor. That would be my luck. I clicked on another article.

About halfway down, I found “Flashbacks vs. Hallucinations,” looked up “flashback,” and read aloud, “A sudden, usually powerful, re-experiencing of a past experience or elements of a past experience.” Wikipedia again. Yep. Angel had a job waiting for her in the future, writing articles for Wikipedia.

I read about flashbacks on two other sites and figured out that the word meant reliving bad stuff from the past. That made me think of Captain Armstrong, when he thought he was back in the desert still fighting in the war but he was really standing in his driveway trying to pick up his newspaper, remembering scary things.

Except, how could I be remembering something I had never seen?

My head hurt.

Maybe I did have a brain tumor.

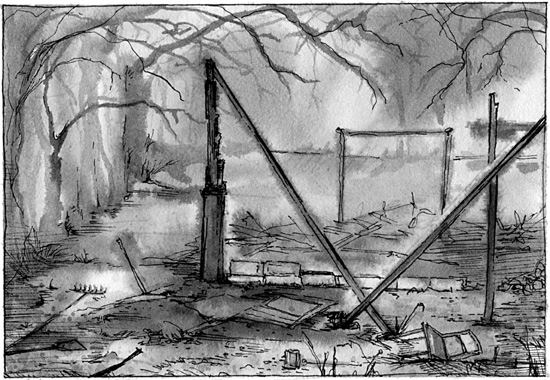

I clicked off the web browser and uploaded the pictures of the Abrams farm to get my mind off hallucinations and flashbacks and Captain Armstrong and scary war things and brain tumors, but they didn’t help much. They reminded me of disaster movies where the camera sweeps across endless fields of everything splatted and exploded. The only thing missing was the doomy-boomy music.

Most of the shots captured ashes and melted stuff. All the black char made me shiver.

Fire. The farm, burning. Cissy and Mom . . . What did I see?

Those flecks—

I shivered, then rubbed my eyes to make that image go away. I had to rub my ears, too, because they were buzzing again.

When I looked up, all I could see were my closed white blinds. I was sitting at the desk in front of my bedroom window, but I always kept the blinds closed and the windows shut at night. I couldn’t shake the feeling that something would jump through the darkness and get me.

Was that normal? I picked at the bows on my nightgown. Am I on the way to getting sick like Mom?

No. I smacked my ears until the buzzing stopped. Not happening. Not going crazy. I was fine.

But I saw things at the Abrams farm. Images that couldn’t have been real.

Maybe they were real. Maybe they were flashbacks, not hallucinations.

“No,” I said out loud this time. I had to rub my arms to keep from shivering again. It was stupid, feeling so cold when it was spring in Mississippi and already hot even with air-conditioning.

I clicked through a few more pictures. More ashes. More soot. I printed the first one and made a note on it.

These ashes might have dead people in them. That’s gross. And kind of sad.

The next picture was the same, and the one after that and the one after that. I didn’t know how journalists and detectives did it, looking at pictures of crime scenes over and over again. These shots only had burned-up wood and farm tools, not bodies and blood or horrible stuff, and my brain already didn’t want to keep studying them. Maybe I wasn’t cut out for journalism, either.

I ticked through pictures of skeleton house boards and scorched trees, then some shots of the area closer to the woods. Normal trees. Grass so green, it almost hurt my eyes. Then I found the corner of Angel’s pink dress, and one image of her sunburned knee. We were thorough investigators—but effective? Not so much. We had a long way to go before we’d be one of those teams people made television shows about.

I shivered all over again when I got to the picture of the brush where I thought I had seen someone hiding, right after my hallucination or flashback or whatever that had been. There was nothing in the brush but trees and leaves. So that wasn’t real either. It was just me being chicken about stuff jumping at me through the darkness.

It wasn’t something I talked about much, being scared of the dark. More like what was in the dark that I couldn’t see. I always thought something had to be there, something awful and dangerous that vanished when I finally made it to a switch and flooded the world with light. Sometimes it was hardest and scariest to see what was right there beside you—what had been there right beside you all along, waiting to snarl and bite you and eat you whole.

My chest got tight from just thinking about how it felt to get stuck in a dark room and have to run for a switch. “I’m a great big baby,” I muttered, tempted to turn off my lamp and pull up my blinds and make myself stare out the window into the night until I just got over it. I had tried that before, lots of times, and it never worked. But I kept doing it whenever I could find the courage, because maybe the next time I’d make it past the panic and I wouldn’t be a baby anymore.

When I stood, my legs shook. I glanced at the picture of the brush where nobody was hiding, then switched off the lamp. Then I went and opened the blinds really fast, before I could wimp out. The second they opened, I stepped toward the desk.

Well?

If something did jump out of the darkness and bust through my window like a rabid fire-breathing lizard on a rampage, I wanted to give it some space.

Quiet pressed into my ears as I stared out the inky glass. If Mom had been home, she would have had the television on in their bedroom, watching true-crime documentaries or gathering recipes off cooking channels. Sometimes she listened to music, and sometimes she played movies. Silence was never a problem when Mom was here.

But Mom’s not here. I hated that so much. Tears tickled my eyelids, but I ground my teeth until they went away. I had already cried enough after I got home, and Dad said Mom would be gone for a while.

A moth smacked against the window, and I almost peed myself. I said something I’d get grounded for if Dad heard me, and closed the blinds as fast as I could. It took a minute before I could breathe enough to stalk back to my desk, click on my lamp, and throw myself into the chair. Still a baby. That completely sucked.

I squinted at the picture of the brush, too ticked off for words—then I squinted harder. My fingers flicked across the laptop keyboard as I pulled the picture into the edit window, cropped it, and magnified it. Again.

And one more time.

I couldn’t be totally sure, but right at the edge of the brush where I thought I had seen somebody standing, Angel had snapped a photo of a shoe. It looked like a black tennis shoe, the kind grown men wore.

I sent the photo to Peavine’s phone with the note that look like a shoe 2 u??

Almost immediately, his text tone sang out, and I read, Kinda. Whaddya thnk?

sumbdy wz watchn.

Who?

dnt knw. the serial killer?

A few seconds went by, then Peavine texted that he had to go to bed.

My eyes shifted from the phone to the picture to the window. My stupid baby brain told me the darkness outside was just like a poisonous copperhead, trying to slither around the edges of my blinds to bite me. Would it get me put in some hospital in Memphis if I glued the blinds to the sill?

Peavine’s mom was great, but I wished she would let him stay up later and talk to me. What should we do with the picture? If I showed it to Dad, he probably wouldn’t think it was anything important. It was just a shoe. I couldn’t even see if there was a leg in it. It might have been a shoe with no person attached to it at all. It wasn’t like the police could do anything with a photo of a shoe, right?

What would a good journalist do to make sense out of this mess?

A good journalist would write.

But I didn’t know what to write. I didn’t even know where to start.

Finally, I opened a document to the side of the photos and typed a list of what I knew for sure about the Abrams case:

1. Old Mr. Abrams got shot, and nobody knows who shot him.

2. The Abrams farm got burned to the ground, and nobody knows who set the fire.

3. Cissy and Doc might be dead or alive, and nobody knows where they are.

After I stared at it a while, I added some possibilities.

4. Mom might have been there.

5. I might have been there.

6. Somebody might have been watching us while we searched.

7. I might be crazy.

Great. Peavine and Angel and I had gone to the farm to search for clues and solve some of the mystery, but we ended up finding nothing but more questions.

I closed the computer lid, switched on the night-light near the foot of my bed, then turned off the lamp. To prove I wasn’t a complete baby, I sat there studying the blinds, making sure the darker darkness didn’t try to get inside.

After a while I got in my bed. Then I got back out of my bed, took my pillow and blanket, and got under the bed instead. For some reason, I didn’t want to close my eyes. I didn’t want to sleep. I definitely didn’t want to dream about anything. What if the dreams turned into hallucinations and I couldn’t wake up? What if—

“Mom?” I tried to breathe but coughed instead. My room smelled like something on fire.

I got out of bed too fast, tangled my feet in my bedspread, and fell to my knees. My hair swung against my cheeks, making me shiver. It was wet. Why was my hair wet? It wasn’t a bath night.

“Mom?” I got up and fought my way out of the bedspread. The muscles in my belly hurt, like the time I lifted Dad’s weights too many times. Nobody met me in the hall outside my room. Silence hung like smoke in the house. No television. No Mom. No Dad.

My heart thumped in my throat, making it hard to swallow. I ran to the hall light switch and flipped it on. Yellow light blazed in a long strip, but darkness still crowded out of my bedroom and the guest bathroom and my parents’ room. Fast as I could, I turned on those switches too.

“Mom!”

Nobody answered. My ears hurt from listening. I shoved open the door to the master bathroom, but nobody was there, either. The closet—no people in there. Out in the hall again, I ran to the kitchen.

Where was Mom? Dad should be home.

Lights. I had to turn them on. Kitchen. Pantry. Living room. Basement. I hit the switch at the top of the stairs, and something rattled down below.

I froze.

Air whistled through my teeth. My fingers dug into my palms. The muscles in my throat ached from wanting to yell for Mom again.

But what if that’s not Mom . . .

Downstairs in the basement, a door closed.

I backed up so fast, I tripped over my nightgown and pitched backward—

My eyes popped open as I swung my arms, trying to keep my balance.

I was standing totally still in the dark, in front of the kitchen sink. A whimper slipped out as I jumped forward and flicked on the light to break the blackness before it reached for me.

What was I doing in the kitchen?

As I eased down from my toes where I had stretched to hit the light switch, my heel ground into something wet that crinkled. I jumped and picked up my foot.

One of my school drinks lay on the floor, where I had crushed the pouch. Nothing much was left in it, though, or it would have made a bigger mess . . . to go along with the chip wrappers and pieces of bread on the floor.

Had I been eating in my sleep? I had heard of sleepwalking, but sleep-eating? Really? My heart slowly moved from gallop to trot, then on down to walk. Little by little, I managed to breathe normally, even though I couldn’t tell if my belly was bigger than usual.

I had completely trashed the kitchen in my sleep. I glanced toward the hall but didn’t see Dad’s light. I hadn’t turned on the hall light, like I did in my dream. Could people hallucinate in dreams? Were dreams just hallucinations anyway?

Of course I dreamed all of that—it hadn’t been real, any more than what I imagined I saw at the Abrams farm. I mean, bits and pieces of it, maybe. My thoughts felt cramped and muddled, so I rubbed the sides of my face.

Nothing came clear.

I looked at the clock on the stove. The only thing I knew for sure was, I needed to clean up the kitchen as fast as I could, because here in not-dream-totally-real-world, it was almost time for Dad’s alarm to buzz.