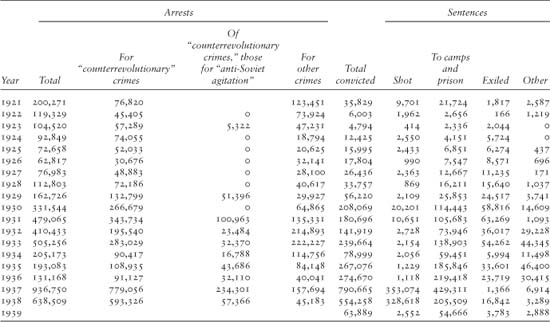

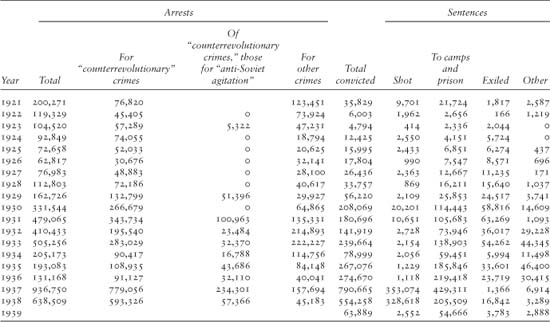

Table 1

Secret Police (GPU, OGPU, NKVD) Arrests and Sentences, 1921-39

Source: GARF, f. 9401, op. 1, d. 4157,11. 201-5.

Anyone who feels like arresting does so. It is no wonder, therefore, that with such an orgy of arrests, the organs having the right to make arrests, including the organs of the OGPU, and, especially, of the police, have lost all sense of proportion.—Central Committee Circular, 1933

At this congress, however, there is nothing to prove and, it seems, no one to fight. Everyone sees that the line of the Party has triumphed.—Stalin, 1934

LITERARY CENSORSHIP in this period provides an example both of ambiguous policies and of direct attempts to construct the regime’s dominant rhetoric and narrative. Since 1917 the Bolsheviks had suppressed publication of books and newspapers from their political opponents. But during the 1920s the Stalinist leadership had often permitted the publication of statements and articles from various oppositionists within the party, at least until the moment of their defeat and expulsion. Trotsky’s works were published until the mid-1920s, and Bukharin continued to publish, albeit within controlled parameters, until his arrest in 1937; he was in fact editor of the government newspaper Izvestia until that time.1

The content of historical works had always played a role in Bolshevik politics. Part of the public dispute between the Stalinists and the Trotskyists in the early 1920s had revolved around Trotsky’s historical evaluation of the role of leading Bolsheviks in his Lessons of October. And in 1929 a letter to the editor of a historical journal on an apparently obscure point of party history touched off a political purge in the historical profession and a general hardening of the line on what was acceptable and what was not.2

By the early 1930s the Stalinists were generally more intolerant of publications from ex-oppositionists, whose writings were scrutinized more carefully. At the end of 1930 Bukharin could still publish statements about his position on various matters, but their content was checked word for word by the Politburo before approval. In one such case, a Politburo directive of October 1930 noted that “Comrade Bukharin’s statement is deemed unsatisfactory…. In view of the fact that the editors of Pravda— were Comrade Bukharin to insist on the publication of his statement in the form in which it was sent by him to the CC—would be forced to criticize it, which would be undesirable, Comrade Kaganovich is entrusted with talking to Comrade Bukharin in order to coordinate the definitive wording of the text of his statement.”3 Bukharin’s statement was eventually published, but only after considerable haggling over its content.

By 1932, however, things had become harder even for veteran party litterateurs. A. S. Shliapnikov, a prominent Old Bolshevik and one of the leaders of the defeated Workers’ Opposition in the early 1920s, was taken to task for some of his writings on the 1917 Revolution. In this case, though, it was not a matter of prior censorship of historical works; Shliapnikov’s 1917 and On the Eve of 1917 had already been published.4This time, the new situation required a formal recognition of “mistakes” and a published retraction from the author; otherwise he would be expelled from the party. In the “new situation,” the worried nomenklatura was taking command of history itself by reshaping historical texts that had already been promulgated. In the Stalinist system, public disquisitions—which were necessarily political—could be “repaired” and history itself could be changed along with them. Chaotic times make ideology and ideological control important in order to “render otherwise incomprehensible social situations meaningful.”5

Despite the general tightening of literary “discipline,” the policy of censorship in the 1932–34 period was uneven. In June 1933 a circular letter from the Central Committee formally prescribed policies for “purging of libraries.” Back in 1930, during the ultraleft upsurge of the “cultural revolution,” the party had insisted on removing literary and historical works by “bourgeois” and oppositionist authors from all libraries. The June 1933 circular, while approving the removal of “counterrevolutionary and religious literature,” along with the works of Trotsky and Zinoviev, took a relatively moderate line on library holdings in general. Works representing “historical interest” were to remain in the libraries of the larger towns, and closed or “special” collections were forbidden, as were mass purges of libraries.6

Even here, the Politburo had difficulty taking control of the situation. The June 13 order was ignored by hotheaded local activists who continued to strip the libraries of books they considered counterrevolutionary. Yemelian Yaroslavsky and other party leaders complained about this to the Politburo, prompting Molotov and Stalin to issue stronger strictures that characterized the purging of the libraries as “anti-Soviet” and again ordered it stopped.7

Later, beginning in 1935, the policy would harden again as Stalin assumed supervision of the Culture and Propaganda department of the Central Committee from Andrei Zhdanov.8 Large numbers of books would be removed from circulation and Stalinist censorship would emerge in its full form. But in the 1930–34 period, policy was still in flux.

Similar ambiguity characterized judicial policy in this period.9 At the beginning of the 1930s an ultraleftist version of “socialist legality” had prevailed. A class-based justice differentiated “class-alien” defendants from the “bourgeoisie,” and those from the working class or peasantry, with the former receiving much sterner treatment at the bar. Legal protections were minimal, with the secret police (OGPU until 1934) having the right to arrest, convict, and execute with only the most cursory (or no) judicial proceedings. Indeed, the Collegium of the OGPU had the right to pass death sentences entirely in secret and “without the participation of the accused.”

During the period of “dekulakization” and collectivization, such legality as existed was completely thrown aside. Lawlessness was the rule as squads of party officials, police, village authorities, and even volunteers arrested, exiled, and even executed recalcitrant peasants without any pretense of legality.10 As early as March 2, 1930, even Stalin recoiled from the chaos and wrote his famous “Dizziness with Success” article, in which he called for a halt to forced collectivization and ordered a reduction in the use of violence against peasants.11 Although the article did result in a general decline in mass terror against peasants, it did not curb the powers of the police (and others) to make arrests as they chose.

Indeed, in the 1932–34 period, the regime sent mixed signals on the general question of judicial repression. Consider the policy toward technical specialists from the old regime. In June 1931 Stalin’s “New Conditions—New Tasks” speech seemed to call a halt to the radical, class-based persecution of members of the old intelligentsia and said that the party’s policy should be “enlisting them and taking care of them.” “It would be stupid and unwise to regard practically every expert and engineer of the old school as an undetected criminal and wrecker.”12 The following month, the Politburo forbade arrests of specialists without high-level permission.13 In the subsequent period, the Politburo intervened on several occasions to protect persecuted members of the intelligentsia and to rein in the activities of secret police officials persecuting them.

An apparently contradictory “hard” signal came a few months later, when a new decree (said to have been drafted by Stalin personally) prescribed the death penalty (or long imprisonment with confiscation of one’s property) for even petty thefts from collective farms. Such harsh measures testify to the climate of paranoia in the top leadership in this period. They also bespeak panic and an inability to control the countryside through any means but repression.

Despite the draconian nature of this law, its application was uneven and confused. The following month, September 1932, the Politburo ordered death sentences prescribed by the law to be carried out immediately.14 Nevertheless, of those convicted under the law by end of 1933, only 4 percent received death sentences, and about one thousand persons had actually been executed.15 In Siberia, property was confiscated from only 5 percent of those convicted under the law. Although the law seemed aimed at collective farm members, commentators argued that class bias should be applied and that workers and peasants should be shown leniency.16 In 1933 the drive was reoriented away from simple peasants and against major offenders; at that time, 50 percent of all verdicts passed under the law had been reduced. By mid-1934 most sentences for theft did not carry prison or camp time.17 It is interesting to note that the Commissariat of Justice was unwilling or unable to report to higher authorities exactly how many people were convicted under its provisions, giving figures ranging from 100,000 to 180,000 as late as the spring of 1936. Despite Stalin’s strictures in the original decree against leniency, by August 1936 a secret decree had ordered the review of all sentences under the “Law of August 7, 1932.” Four-fifths of those convicted had their sentences reduced and more than 40,000 of them were freed at that time.18

In April 1933 a show trial of engineers was held in Moscow in which technicians “of the old school” were accused of espionage and sabotage on behalf of Great Britain.19 The “Metro-Vickers” trial was the latest in a series of such open proceedings against engineers and technicians of the old regime that included the Shakhty trial of 1928 and the trial of the Industrial Party in 1930. The symbolism conveyed in these proceedings, which seemed to reinforce repressive trends, was that older technical specialists from the old regime were not to be trusted and that party members and Soviet citizens must be increasingly vigilant against enemies. Even here, though, there was ambiguity. Several of the defendants were released on bail before the trial. No death sentences were handed out, and two of the defendants received no punishment at all. According to the most recent study of the trial, the proceedings seemed to indicate indecision within the Soviet government, perhaps reflected in the court’s hedging statement that it “was guided by the fact that the criminal wrecking activities of the aforesaid convicted persons bore a local character and did not cause serious harm to the industrial power of the USSR.”20 Nevertheless, a political trial is a political trial, and the Metro-Vickers prosecutions sent a hard signal.

Almost immediately, the regime did another volte-face back in the direction of sharply relaxing repression. During the Civil War and again during collectivization, the secret police had operated tribunals for the purposes of handing down drumhead sentences of death or hard labor for political enemies. The vast majority of those executed during the storm of dekulakization and collectivization were victims of three-person police “troikas.” On 7 May 1933 the Politburo ordered the troikas to stop pronouncing death sentences.21

The next day, a document carrying the signatures of Stalin for the Central Committee and V. M. Molotov for the government ordered a drastic curtailment of arrests and a sharp reduction in the prison population. Half of all prisoners in jails (not, in should be noted, in camps or in exile) were to be released. The power to arrest was sharply restricted to police organs, and all arrests had to be sanctioned by the appropriate judicial procurator. The “Instruction to All Party-Soviet Workers, and All Organizations of the OGPU, Courts, and Procuracy” ordered an end to “mass repression” of the peasantry:

The Central Committee and the Council of People’s Commissars, (SNK) [the government] are of the opinion that, as a result of our successes in the countryside, the moment has come when we are no longer in need of mass repression, which affects, as is well known, not only the kulaks but also independent peasants [yedinolichniki] and some kolkhoz members as well…. Information has been received by the Central Committee and the Council of People’s Commissars that makes it evident that disorderly arrests on a massive scale are still being carried out by our officials in the countryside….

It is no wonder, therefore, that with such an orgy of arrests, the organs [of state] having the right to make arrests, including the organs of the OGPU, and, especially, of the police [militsia], have lost all sense of proportion. More often than not, they will arrest people for no reason at all, acting in accordance with the principle: “Arrest first; ask questions later!” …

It would be wrong to assume that the new situation and the necessary transition to new methods of operation signify the elimination or even the relaxation of the class struggle in the countryside. On the contrary, the class struggle in the countryside will inevitably become more acute. It will become more acute because the class enemy sees that the kolkhozy have triumphed, that the days of his existence are numbered, and he cannot but grasp—out of sheer desperation—at the harshest forms of struggle against Soviet power….

Therefore, we are talking here about intensifying our struggle against the class enemy. The point, however, is that in the present situation it is impossible to intensify the struggle against the class enemy and to liquidate him with the aid of old methods of operation because these methods have outlived their usefulness. The point, therefore, is to improve the old methods of struggle, to streamline them, to make each of our blows more organized and better targeted, to politically prepare each blow in advance, to reinforce each blow with the actions of the broad masses of the peasantry.22

The language was ambiguous: although the former sharply repressive policy had been correct and successful, it must end. Although the level of “class struggle” with enemy elements in the countryside would “inevitably sharpen” and the party’s struggle with the class enemy “must be strengthened,” it was nevertheless time for a relaxation in arrest and penal policy.

On the face of it, such language represents the usual and cynical attempt to initiate a new policy by praising the discarded one and blaming local implementers who had “distorted” it. After all, the center had encouraged much of the violence it now condemned in what appears to be a break with previous policy. But in another sense, the document was consonant with others of the period that sought to concentrate more and more authority in Moscow’s hands. In addition to admitting that blind mass repression was inefficient, the leadership wanted to get control of the situation by putting repression into the hands of Moscow officials rather than those of local organs: blows against the enemy would thus be “more organized” and “better targeted.” In this sense, the document did not in itself necessarily imply less violence but rather violence more tightly directed from the center. In any case, there is evidence that this decree had concrete results. In July 1933 Stalin received a report that in the two months since 8 May 1933 the population of prisons had indeed been reduced to a figure below four hundred thousand.23

In the following two months, the Politburo decided to make two administrative changes that also seemed to point in the direction of enhancing legality: the creation of Office of Procurator of the USSR (roughly, attorney general) and of an all-Union Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD). Up to this time, each constituent republic of the USSR had its own procurator, who had limited powers to supervise or interfere in the activities of central administrative, judicial, and punitive organs (including the secret police). In principle, the new procurator of the USSR was to have jurisdiction over all courts, secret and regular police, and other procurators in the entire Soviet Union. Legally speaking, an all-Union “civilian” judicial official thus received supervisory powers over the secret police. As with procurators, each republic had previously had its own Commissariat of Internal Affairs, with supervisory responsibilities over republican soviets, regular police, fire departments, and the like.

The position of procurator is an element of continental and Russian law. Unlike Anglo-Saxon “prosecutors,” a procurator is not only the representative of the people in an adversary proceeding against defense counsel. Indeed, the principal function of Russian procurators from the time of Peter the Great was administrative as much as judicial; it was to exercise supervision (variously nadzor or nabliudenie) over state bodies and over their proper and legal implementation of state measures.24

A February 1934 decree announced the formation of the NKVD USSR, abolished the OGPU and incorporated its police functions into the new organization.25 Moreover, according to the new regulations, the NKVD did not have the power to pass death sentences (as had the OGPU and its predecessors the GPU and CHEKA) or to inflict extralegal “administrative” punishments of more than five years’ exile. Treason cases, formerly under the purview of the secret police, were, along with other criminal matters, referred to the regular courts or to the Supreme Court. Similarly, at this time the secret police lost the power to impose death penalties on inmates of their own camps. Special territorial courts under the control of the Commissariat of Justice, rather than of the police, were established in the regions of the camps, and cases of crimes (like murder) committed in the camps were now heard by those judicial bodies.26

Combined with the decrees on the USSR Procuracy, the formation of the NKVD seemed to herald a new era of legality, and contemporary observers were favorably impressed with what appeared to be moves in the direction of reduced repression.27 Other decisions support the impression of a relaxation in 1933–34. As we shall see, though, in 1937 and 1938 legal protections would become dead letters, as the unfettered sweeps of the police netted huge numbers of innocent victims who were jailed, exiled, or shot without procuratorial sanction or legal proceedings or protection of any kind. But this was 1934, and a number of key events between then and 1937 would dramatically change and harden the political landscape; these included the assassination of Politburo member S. M. Kirov at the end of 1934.

In June 1934 a Politburo resolution quashing the sentence received by one Seliavkin strongly censured the OGPU for “serious shortcomings in the conduct of investigations.”28 In September a memo from Stalin proposed the formation of a Politburo commission (chaired by V. V. Kuibyshev and consisting of Kaganovich and State Procurator Akulov; A. A. Zhdanov was later added) to look into OGPU abuses. Stalin called the matter “serious, in my opinion” and ordered the commission to “free the innocent” and “purge the OGPU of practitioners [nositely] of specific ‘investigative tricks’ and punish them regardless of their rank.”

Thus, in response to Stalin’s recommendation, the Kuibyshev Commission prepared a draft resolution censuring the police for “illegal methods of investigation” and recommending punishment of several secret police officials. Before the resolution could be implemented, however, Kirov was assassinated. The mood of Stalin and the Politburo changed dramatically, and the recommendations of the Kuibyshev Commission were shelved in a period characterized by personnel changes in the police, scapegoating of a poor harvest and industrial failures in 1936, the rise of German fascism, and the resurgence of spy mania in 1937.29

Another 1934 decree complicates the picture even further. Simultaneously with the decision to create the NKVD, the Politburo—at future NKVD chief Genrikh Yagoda’s request—created a Special Board of the NKVD (Osoboe Soveshchanie) to handle specific cases. Yagoda and other police officials had worried about losing all judicial-punitive functions and had lobbied to retain some of them. Officials of justice and procuracy agencies pressed to concentrate all punitive functions in judiciary bodies. Stalin refereed the dispute, siding with the legal officials but giving the new NKVD the Special Board.30 According to the new scheme, all crimes chargeable under the criminal code were to be referred to and decided by one of the various courts in a judicial proceeding. But the Special Board had the right to exile “socially dangerous” persons for up to five years to camps, abroad, or simply away from the larger cities.31

Certainly, compared to the former powers of the OGPU, the general trend of 1934 represented a sharp restriction on the independent punitive power of the police. On the other hand, several aspects of the Special Board ran quite contrary to legality. First, the Special Board consisted only of secret police officials. Aside from the “participation” ex officio of the USSR procurator, no judicial officials, judges, or attorneys were involved. Second, the “infractions” coming under the purview of the Special Board were not criminal offenses as defined in the criminal code; formally it was not a crime to be a “socially dangerous” person, but under these provisions it was punishable by the police in a nonjudicial proceeding. It was therefore up to the police to decide what was “socially dangerous” and who could be punished under that category. Third, the Special Board passed its sentences without the participation or even presence of the accused or his or her attorney, and no appeals were envisioned. Because of the ability to punish persons who had committed no definable crime (an “advantage” later touted by Yezhov), the activities come under the heading of administrative, extrajudicial punishments, a category hardly consistent with formal legality.

These contradictory judicial texts lend themselves to several possible interpretations: conflicting hard and soft factions, a terrorist Stalin trying to cover his purposes with “liberal” maneuvers, or a genuine moderate trend that was later derailed. But all of them point toward regularization and centralization of police powers in the hands of fewer and fewer people.

Leadership attitudes toward party composition provide our final example of ambiguous elite policies in the 1932–34 period. In early 1933 the party leadership decided to conduct a membership screening, or purge [chistka, meaning a sweeping or cleaning], of the party’s membership. Purges had been traditional events in the party’s history since 1918 and had been aimed at a wide variety of targets. Most often, the categories of people specified for purging were not explicitly related to political oppositional or dissidence but included targets like careerists, bureaucrats, and crooks of various kinds.32 Members of oppositionist groups were not mentioned in the instructions. Still, the inclusion of categories like “double-dealers,” “underminers,” and those who refused to “struggle against the kulak,” in a purge announced at the same plenum that attacked A. P. Smirnov, clearly invited the expulsion of ideological opponents.33

It would be a mistake to regard the 1933 chistka as having been directed solely against members of the opposition. The largest single group expelled were “passive” party members: those carried on the rolls but not participating in party work. Next came violators of party discipline, bureaucrats, corrupt officials, and those who had hidden past crimes from the party. Members of dissident groups did not even figure in the final tallies.34 Stalin himself characterized the purge as a measure against bureaucratism, red tape, degenerates, and careerists, “to raise the level of organizational leadership.”35 The vast majority of those expelled were fresh recruits who had entered the party since 1929, rather than Old Bolshevik oppositionists. Nevertheless, the 1933 purge expelled about 18 percent of the party’s members and must be seen as a hard-line policy or signal from Moscow.

Moreover, such purges potentially affected not only ideological groups but also various strata within the party. Traditionally, purges could strike at the heart of local political machines insofar as Moscow demanded strict verification of officials. On the other hand, the sword could strike the other way. Because they were usually carried out by local party leaders or their clients, party purges could be used by them to rid the party of rank-and-file critics or people the local party “family” considered troublemakers.

The chistka can be seen in another light not directly connected with real or imagined political dissidents or possible plans for terror. If, as we have argued, the dangerous “new situation” of 1932 threatened the regime’s control (that is, the nomenklatura’s position), it would make sense for the elite to close ranks, prune the party, and thereby restrict the size of the politically active strata of society. The chistka served these interests by “regulating its composition” and closing off access to it by “crisis” or “unstable” elements in a time of troubles. Thus the chistka may have been seen by the leadership not as a prelude to anything but rather as a survival mechanism for the nomenklatura.

At the beginning of 1934 Stalin spoke to the 17th Party Congress (dubbed the Congress of Victors by the party leadership). On the one hand, he noted that the oppositionist groups had been utterly defeated, and their leaders forced to recant their errors. Indeed, former oppositionists Bukharin, Rykov, Tomsky, and others were allowed to speak to the congress in order to demonstrate a new party unity that Stalin proclaimed. On the other hand, however, he noted that “unhealthy moods” could still penetrate the party from outside: “the capitalist encirclement still exists, which endeavors to revive and sustain the survival of capitalism in the economic life and in the minds of the people of the USSR, and against which we Bolsheviks must always keep our powder dry.” Stalin’s ambiguous (or perhaps dialectical) text thus combined the policies of stabilized legality with continued vigilance.

He criticized those who favored a weakening of state power and controls, arguing that even though the party was victorious and the class enemies were smashed, the state could not yet “wither away.” Rightists and moderates had suggested that the victory of the party’s General Line in industry and agriculture meant that the state could relax its control and reduce the power of its repressive mechanisms. In this connection, Stalin repeated his theoretical formula that as the Soviet Union moved toward victorious socialism, its internal enemies would become more desperate, provoking a “sharper” struggle that precluded “disarming” the state. Thus, while proclaiming victory and implying the end of mass repression, Stalin left the theoretical door open for the continued use of repression on a more selective basis. (He had previously ordered an end to mass repression in the countryside while simultaneously arguing that the struggle with enemies was becoming “sharper.”) Nevertheless, the specific remedies he proposed for the remaining “problems” were in the benign areas of party education and propaganda rather than repression.

Stalin’s nomenklatura listeners, beset by crises on all sides, certainly were glad to squelch any talk of “disarming.” On the other hand, they must have been less pleased by the second part of his remarks, “Questions of Organizational Leadership.” Here, he complained about high-ranking “bureaucrats” who rested on their laurels and were lax about “fulfillment of decisions.” The “incorrigible bureaucrats” he chastised were members of the nomenklatura. Rudzutak had spoken for this elite the year before when he said of Stalin, “he is ours.” Now, however, Stalin sounded a more sour note when he implied that the nomenklatura officials must themselves obey their own party line—and that of the leader of the party. This was the beginning of diverging interests between Stalin and the elite that backed him, and although their alliance would continue, signs of a rift were already present in early 1934.36

The year 1934 evokes positive memories in the Soviet Union. It began with famine and violent class war in the countryside, but also saw a series of reforms in the direction of a kind of legality, or, to use Gramsci’s terms, hegemony rather than domination. Memoirs recall 1934 as a “good” year when the mass repression of the previous period had ended, and it seemed that official statements and new judicial arrangements heralded a period of relative stability and relaxation. Arrests by the secret police fell by more than half (and political convictions by more than two-thirds) from the previous year, reaching their lowest level since the storm of collectivization in 1930 (see table 1 and the appendix). The regime had made peace with the old intelligentsia and seemed to be replacing repression with political education as its main political tool. After the tumult of collectivization and hunger, the economy was improving, and the year ended with the abolition of bread rationing throughout the country.

Given the eruption of terror just a few years later, we now know that the stability of 1934 was temporary. In fact, as we have seen, moderation and softening of the regime alternated and indeed coexisted with the diametrically opposed policy of repression. On the questions of treatment of dissidents, literature, and judicial policy, we have seen that moderate and hardline policies were jumbled together in a contradictory way that suggested a series of vacillations more than any coherent pattern.

In one view, these oscillations represented a kind of jockeying for position between hard and soft factions in the top leadership. The question, of course, is what was Stalin’s position? Because he was a crafty politician always careful not to reveal too much, it is exceedingly difficult to divine his thoughts and plans. Some observers saw the political situation of 1932–34 as one in which different groups contended for Stalin’s favor.37 According to this line of reasoning, Stalin allowed his subordinates to contend with one another, with the result being the alternation of initiatives and emphases. Indecision therefore made 1934 a kind of crossroads at which several alternative paths—including a continuation of moderation—were open and terror was neither planned nor inevitable but rather a function of contingent factors that arose later.

Table 1

Secret Police (GPU, OGPU, NKVD) Arrests and Sentences, 1921-39

Source: GARF, f. 9401, op. 1, d. 4157,11. 201-5.

From another view these waverings of 1932–34 constituted a prelude to terror. Indeed, many scholars believe that even then Stalin was predisposed toward repression and mass violence. According to this view, the hard-line policies of the period can be associated with a Stalin who promoted repressive policies in order to lay a groundwork for terror but was blocked by a moderate faction that favored relaxation and was often able to implement softer policies or at least force Stalin to back down temporarily. Opposition to Stalin, therefore, created a situation in which it would be necessary for him to neutralize the moderates in order to continue and indeed expand his repressive plans. In this view 1934 was merely an illusion, a hiatus in which there was little potential for any outcome other than terror.38

On this point it may be worthwhile to reflect briefly on what the 1932–34 period shows us about repression and Bolshevik mentality. Looking at the repressive or hard-line strand of policies, it is easy to have the impression of a fierce regime exercising strong totalitarian control. Without a doubt, the regime was capable of launching bloody and violent repression, as the collectivization of agriculture had shown.

But such repressive policies may well betray another side of the regime and its self-image. Regimes, even those with transformational goals, do not need to resort to terror if they have a firm basis of social support. They do not need messy, inefficient, out-of-control campaign-style politics, including mass campaigns of terror, if they have reliable and efficient administrations that govern with any degree of popular consensus. If governments are sound and firmly based, they do not need continued repression to survive and to carry out their goals. The Stalinist regime clearly did need such repression, or at least thought it did.

Given what must appear to us to be a paranoid and pathological institutional mentality and history of political violence, it is all the more remarkable that moderate and legalist policies periodically surfaced among the Stalinists. How can we explain the other, more moderate strand in Bolshevik policies in this period? Although such initiatives, sometimes bordering on constitutionalism and legalism, lost ground to the repressive alternative after 1935, they did not die out completely; they appeared even at the height of the terror and after.39

The answer is that in addition to being ideological fanatics willing to use any means, including violent “revolutionary expediency,” the Stalinists were also state builders attracted to “socialist legal consciousness.” USSR Procurator Andrei Vyshinsky saw no contradiction between these two goals, noting that they were compatible parts of the party’s policy of “revolutionary legality.”40 Bolsheviks—including Stalin at various times —recognized that modern economies required modern states, efficient bureaucracies, predictable administration, and some measure of security for the political elite. The tension between voluntarist campaigns and arbitrary repression on the one hand and state building and orderly administration on the other marked the entire Stalin period; these two sets of policies alternated and overlapped with each other. As one scholar has noted, the Stalinist system was “two models in one,” and tension between the two ran throughout the Stalin and post-Stalin periods.41 We shall see this dynamic at work in the next period, when a political assassination raised the political temperature but provoked familiar contradictory responses.

In the summer of 1934 Politburo members advocated releasing several political figures convicted of anti-Soviet crimes. In one such case, Commissar of Defense Voroshilov noted that this was possible because “the situation now has sharply changed, and I think one could free him without particular risk.”42 There was the feeling at the top that the social struggle was calming down and that the previous policy of class struggle and maximum repression was being replaced by one in which the regime could feel strong enough to grant a certain measure of democracy without fear of being overthrown. L. M. Kaganovich wrote that the reform of the secret police “means that, as we are in more normal times, we can punish through the courts and not resort to extrajudicial repression as we have until now.”43

Of course, no one in the Politburo was advocating abandoning the party-state dictatorship. As Stalin had said at the 17th Party Congress, “We cannot say that the fight is ended and that there is no longer any need for the policy of the socialist offensive.” On the other hand, Stalin explicitly joined other Politburo members in proposing some kind of relaxation of that dictatorship, at least experimentally. The increased repression in later years “should not cast doubt on the intentions of Stalin and his colleagues in 1934.”44 At the beginning of 1935 he proposed a new electoral system with universal suffrage and secret-ballot elections. Confident that the regime was more and more secure and that sharp repression could be tempered with legality, Stalin wrote in a note in the Politburo’s special folders, “We can and should proceed with this matter to the end, without any half-measures. The situation and correlation of forces in our country at the present moment is such that we can only win politically from this.”45 Even as late as 1937, when many of these “reforms” had been abandoned, there seems to have been some kind of attempt to democratize the electoral process and to “trust” the population to support the Bolsheviks.46

Thus one need not necessarily find the apparently hard and soft policies of 1932–34 to be mutually exclusive or sharply contradictory. Each was a means to an end: taking and maintaining control over the country in order to further the revolutionary program. Peasant revolt and starvation, conspiracies and platforms of former party leaders, dissident youth groups, and even a lack of iron discipline among serving Central Committee members had combined to frighten the nomenklatura elite and threaten its hold on power. In response, leaders sought to increase party discipline, strengthen judicial and police controls, and regulate the composition of their party. In these areas, both hard and soft policies had one common aspect: they sought to increase power exercised by the Moscow center. Even the legalist policies reviewed above, including reducing the number of arrests and insisting on judicial procedures, had the effect of tightening Moscow’s control over these activities. By regulating arrest procedures, even in the direction of legality and procuratorial control, the Stalinists were asserting their right to control the entire judicial sphere. In this light, both hard and soft initiatives were parts of a drive (a defensive drive, in the nomenklatura’s view) to centralize many spheres in a climate that was improving but still perceived to be dangerous.