G. M. Malenkov

Comrades, a significant number of the expellees is made up of people whom we cannot include in the category of our enemies…. You realize that such an incorrect attitude to the expellees is dictated not by reasons of vigilance but by a striving by certain Party officials to protect themselves against any eventuality. —N. I. Yezhov, 1936

DOCUMENTS FROM ROUGHLY the first half of 1936 indicate a continuing desire by the top party leadership to ease up on uncontrolled repression. Each year from 1933 to 1936 the number of both political and nonpolitical arrests declined. In this period there was a two-thirds decrease in arrests for “political,” counterrevolutionary crimes (Article 58 of the criminal code), from 283,029 in 1933 to 91,127 in 1936. Arrests for nonpolitical offenses fell by more than 80 percent in the same period, from 222,227 in 1933 to 40,041 in 1936.1 Numerous texts relate to judicial policy and pertain to nonparty urban and rural victims of previous waves of repression in 1933–35. Several of these are connected to Andrei Vyshinsky, procurator general of the USSR, who has sometimes been seen as an advocate of procedural legalism (if not legality) and even as an opponent of indiscriminate terror (if not terror itself).2 For example,

Residence in localities in the USSR subject to special measures is to be permitted to dependents of persons removed from these localities: to dependents, whose family is engaged in socially useful work or to students, that is, to those people who are in no way personally to blame for anything.3

It is proposed to the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and the AllUnion Central Council of Trade Unions that persons deported from Leningrad in 1935 who had not been found guilty of any specific crimes, not be deprived of their voting and pension rights during their period of exile.4

Local party secretaries had expelled large numbers of party members in the verifications and exchanges of party documents in 1935. Everyone could find political advantage in these screenings. For the nomenklatura as a whole, they made party membership more exclusive and thus restricted membership in the elite strata of political participation. By weeding out nonparticipant and inactive members who simply used party membership for their own interests, the purges would supposedly make the party a more efficient machine.

The purges also had particular advantages for particular groups and strata, and these advantages illustrate conflicting interests within the nomenklatura elite. For Stalin and the upper circle, purges could be used to discipline local leaders by pruning their patronage machines, or “family circles,” and also offered the possibility of catching a few political dissidents and conspirators in the process. For the regional and local party secretaries who actually carried out the operations on the ground, the purges provided an opportunity to rid themselves of bothersome critics and individuals with political aspirations who did not belong to the local machine. Local leaders could also demonstrate their “vigilance” by expelling rather large numbers to run up the total for Moscow.

Even though we saw in the last chapter that Moscow sought to control, focus, and rein in the indiscriminate local expulsions, the screening operations remained in the hands of local leaders, who naturally used them to their own advantage. The archives for early 1936 are filled with long lists of persons whose expulsion was routinely confirmed at the provincial level in early 1936. Typically, they took the following form, with dozens on each page and without any personal details or individual circumstance:

From the protocol of the meeting of the Buro of the _______ Provincial Committee of the VKP(b) on [date]:

[Name of expelled], party card no. _______.

The decision of the [district] District Committee of the Party no. _________ of [date] on the expulsion from the ranks of the party of ________ —is confirmed.5

Sometimes, though, the expulsions threatened well-connected members of local political machines. This often happened at local purge meetings when rank-and-file party members made accusations against their superiors. Such criticism from below had to be blunted and reversed by the local elite in order to protect “their people.” Local machines closed ranks to protect their own from popular criticism, using the power that regional and local party leaders had over administration of justice, and expulsions of protected persons were often reversed by their protectors as being “inexpedient.” Convenience for the party family circle outweighed any consideration of formal justice, and the possible guilt or innocence of the factory director had no bearing on the political decision of his case.

Friction between rank-and-file party members and their local leaders was often more serious, and lower-level victims of party expulsions were able to use status differences and conflicts within the nomenklatura to fight back. Complaints and appeals from expelled members, accompanied by denunciations of the officials who had expelled them, reached the highest echelons of the party. There, in some cases, Moscow-based senior party leaders took up the cause of the “little person,” as appellants were often called. Such intervention might happen when the accused official had highly placed enemies eager to embarrass him, when the Politburo wanted to strike some balance or inflict some blow against the middle level, or when Stalin decided to make a propaganda point by publicly posturing as a defender of “little people.”

The June 1936 plenum of the Central Committee took up these questions of expulsions from the party and appeals from those expelled. The minutes of this meeting illustrate important points about variant texts, multiple narratives, levels of information, and how they were used in party leadership struggles.

Minutes of the discussions of Central Committee plenums exist in the archive in several versions. The raw minutes were taken down by stenographers, typed up into an “uncorrected stenogram,” and distributed to the speakers, who had the right to edit and correct their remarks to produce a second textual version, the “corrected stenogram.” The top party leadership (Stalin and his staff in the Secretariat) then prepared and printed a “stenographic report”—a third version—for formal distribution to members of the Central Committee and other important party officials charged with implementing and interpreting the decisions of the meeting. Finally, at the fourth level, abridged and sanitized versions of some of the resolutions and speeches were presented to the general public in Pravda, as printed speeches, summary editorials, or didactic articles.

For this reason, it is instructive to think of Central Committee plenums as ritualized performances intended to produce authoritative and useful texts for particular audiences. Such variant texts fulfilled a function that one scholar has called “concealment” within the master transcript. “By controlling the public stage, the dominant can create an appearance that approximates what, ideally, they would want subordinates to see.”6 Moreover, one’s role in the production and distribution of texts was a sign of power. Access to information—and, just as important, access to knowledge about what was missing from or added to the less complete transcripts below one’s position—was an important part of the stratification of power. Knowledge of the different transcripts was power.

The following texts illustrate these points. They are part of Yezhov’s report to the June 1936 plenum of the Central Committee, combined with what may have been a short speech by Stalin. The subject was the appeal and readmission process for those expelled in the party membership screenings of 1935–36. This was a sensitive and extremely important personal issue for the rank-and-file members who had been expelled: would it be possible to reenter the party? For the nomenklatura, assessing blame for the “mistakes” was a political issue.

Although the lowest-level, public transcript revealed very little about the plenum, it was not completely devoid of information. A short notice in Pravda announced that a plenum of the Central Committee had taken place during 1–4 June 1936. According to the laconic announcement, attendees had discussed adoption of a new constitution, questions of rural economy, and procedures for considering appeals from those expelled in the just concluded verification and exchange of party documents. In connection with this last issue, Pravda noted that Yezhov had given a report and that decisions were reached on the basis of his report as well as on “words from Comrade Stalin.”7 No corresponding Central Committee resolution was published, but a subsequent series of press articles reported that lower-level party officials had taken a “heartless attitude” toward party members, had expelled many of them for simple nonparticipation in party life, and had been slow to consider appeals and readmissions of those wrongly expelled.8

Careful readers of even this minimal public text could discern the outlines of something a bit broader. First, the press formulation “on the basis of Comrade Yezhov’s report and words from Comrade Stalin” was unusual. It suggested that somehow Yezhov’s speech was not sufficient or completely authoritative: additional “words” from Stalin had been required. What were these “words”? A speech? An order? Second, by blaming low-level party officials for “mistakes,” the Central Committee’s formulation suggested a rift within the nomenklatura elite about who was to blame for the repression of innocent rank-and-file members. Those with access to more authoritative transcripts knew more. There were important and revealing differences among the various accounts and texts.

We move now to private and public versions of the transcript: the printed text prepared for distribution to party insiders versus the original transcription. Yezhov’s speech and Stalin’s remarks are the keys here.

In the original version of Yezhov’s speech, transcribed at the time, he said:

YEZHOV: Comrades, as a result of the verification of Party documents, we have expelled over 200 thousand Party members.

STALIN: That’s quite a lot.

YEZHOV: Yes, quite a lot. I’ll talk about it….

STALIN: If we expel 30,000—(inaudible), and if we also expel 600 former Trotskyists and Zinovievists, then we would gain even more from that.

YEZHOV: We have expelled over 200 thousand Party members. Some of the expellees, Comrades, have been arrested.9

But in the final version from the printed Stenographic Report prepared for broad party leadership distribution, the text became:

YEZHOV: You know, Comrades, that during the verification of Party documents we have expelled over 200 thousand Communists.

STALIN: That’s quite a lot.

YEZHOV: Yes, that is quite a lot. And this obligates all Party organizations all the more so to be extremely attentive to members who have been expelled and who are now appealing.10

Stalin’s interjection, recorded only in the most private transcript, that it would have been better to expel six hundred “real” enemies than thousands of rank-and-file members suggests dissatisfaction with the results of the membership screenings that Yezhov had administered. But it also raised dangerous questions about the basic relationship between leaders and led in the party. This incendiary remark could be interpreted to mean that those who carried out the verification and exchange of party documents (including Yezhov and the network of regional secretaries) had missed the boat, failing to get the real targets of the operation and expelling innocent people. Were the “enemies” expelled not “real enemies”? Although Yezhov and other leaders were at pains to repeat that the expulsions had been more or less necessary, Stalin’s remark could suggest the opposite to rank-and-file victims of the screenings: loyal and innocent party members like they (who even Yezhov had admitted were not enemies) had their lives ruined because of nomenklatura “mistakes.” Suggesting as it did questions of basic justice, hierarchy, and the legitimacy of the party leadership, the nomenklatura did not want such sentiments aired. That part of the text therefore had to be kept secret and was reserved for the private elite version of reality.

Accordingly, Stalin’s original remark was excised even from the printed stenographic report of the plenum, which contained a more benign version designed to indicate Stalin’s fatherly concern, while shielding the reputation of the party elite.11 According to the archives, it is not clear that he made a speech to the plenum at all. There is no original transcript of any speech from him. Nevertheless, in the final created text, we find remarks from him:

I would like to say a few things concerning certain points which in my opinion are especially important if we are to put the affairs of the Party in good order and direct the regulating of Party membership properly.

First of all, let me say something concerning the matter of appeals. Naturally, appeals must be handled in timely fashion, without dragging them out. They must not be put on the shelf. This goes without saying. But let me raise a question: Is it not possible for us to reinstate some or many of the appellants as candidate members?12

The sanitized version also allowed Yezhov to associate himself with Stalin’s populist concern, even though he never actually said, “And this obligates all Party organizations all the more so to be extremely attentive to members who have been expelled and who are now appealing.”

In the final version of the plenum transcript, the upper nomenklatura was not particularly eager to reveal that the criticism of regional party secretaries was more severe, and that one of them, the powerful first secretary in Kiev Pavel Postyshev, had been a specific target, even a scapegoat, for the excessive expulsions. The following passage, from Yezhov’s original speech, was cut from the disseminated version:

YEZHOV: In the small district organizations it is the Secretary of the District Committee who directly handles the exchange of documents. He is under obligation to talk to the Party member whose card he is replacing.

POSTYSHEV: What do you mean “talk to”?

YEZHOV: You see, Pavel Petrovich, what I mean by “talking,” there are cases in your organization, in Kiev, for instance.

POSTYSHEV: In what district?

YEZHOV: I’ll tell you in a minute … petty questions of the following sort: “What is the law of diminishing fertility? What is money?” etc.

POSTYSHEV: Such a discussion is important.

YEZHOV: That discussions take place is important…. [But] we are against [this kind of] discussion. The CC did not have such discussions in mind when it said that a Party member must be summoned.13

If this section were not excised, the text would have sent the message that some powerful party secretaries were being harshly attacked, and this could undermine obedience up and down the party chain of command.

Even in the absence of useful performative speech, a final textual reality had to be produced for an expanded audience of party officials below Central Committee rank whose job it was to explain the plenum to the rank-and-file members. The intended message of this “semiprivate” (party) transcript was carefully crafted: (a) there had been some incorrect expulsions from the party, but they were a minority, (b) most of those expelled were not dangerous enemies, (c) too many “passive” members had been expelled, (d) “certain Party officials” had been careless about all this and were to blame, and (e) Stalin had taken a personal interest in these questions, adopting the position that many of those expelled—perhaps more than Yezhov had envisioned—could be readmitted to the party.14 Thus Yezhov’s “final” text included liberal sentiments he was not known for:

YEZHOV: We cannot, however, place the great mass of the expellees in the category of our enemies…. A part of them shall be reinstated after their appeals have been reviewed or they may be allowed to return to the ranks of our Party after amending their conduct. Meanwhile, Party organizations deal indiscriminately, mechanically, with all of the expellees from this category without looking into the reasons why they were expelled from the VKP(b)….

Out of the total number of Communists who had participated in the exchange of Party documents, approximately 3.5% were not issued their Party cards, and the question of their expulsion from the Party has been raised. From these 3.5%, about a half fall into the category of so-called passive membership or, as they are called in many places, “ballast.”

STALIN: What percent?

YEZHOV: 3.5% have not been issued Party cards,—out of this group half fall into the passive category. Not an insignificant percent, as you can see. Such a percentage of Party members and candidate members belonging to the passive category is too high.15

The differences between the printed stenographic report and the public press version reveal that the Politburo’s condemnation of party secretaries for excessive expulsions of the rank and file was harsher and more far-reaching than it wished to advertise. The public version, in contrast to the one for the middle level of the Party, vaguely suggested that some regional secretaries were to blame for unjust repression of the party rank and file. The secret uncorrected stenogram was even harsher, castigating party secretaries with the pejorative chinovnik (a tsarist-era arbitrary bureaucrat), “worse than our enemies,” and directly accusing them of a perversion of vigilance by inflicting punishment on party members to “insure themselves” against being considered soft. The stenogram also specifically attacked a very high ranking official for such arbitrary punishment of innocent party members, an event missing from versions aimed at broader audiences.

Stalin interrupted Yezhov twice (on the question of total numbers expelled and on the percentage of “passives” expelled), indicating both his disapproval of the extreme way Yezhov had conducted the screenings and a desire to pose as the righter of wrongs against “little people.” Only his sanitized interjections “How many?” and “What percent?” were printed in the stenographic report. This, along with the public transcript associating “words of Comrade Stalin” with the liberalized attitude toward appeals, communicated the symbol of Stalin as defender of the little person. Yet his actual interruption of Yezhov’s speech at the point when the numbers of expulsions was discussed suggests more than just posturing or tactics.

After the June plenum, substantial numbers of expelled rank-and-file members were readmitted on appeal. But most were not. Even if Stalin had decided that the mass screenings had not hit the right targets, it was politically impossible to admit it or openly to correct the “mistake” on a large scale. To do so would have cast doubt not only on his own leadership but on the legitimacy and prerogatives of the nomenklatura itself, which had carried out the operation against those beneath it. Those capriciously expelled therefore paid the price to save the nomenklatura’s face.

Stalin’s interjections and his concluding remarks implied a generous approach to rank-and-file members. According to the original uncorrected stenogram, his remarks to the June 1936 plenum speech had not been foreseen in the preplenum agenda, a document traditionally planned by the Politburo and distributed in advance to Central Committee members. His words, if they were in fact uttered, were “not stenogramed.” This notation and a blank page appear in the original plenum version in the archives.16 What, then, were the origins of the remarks that appeared in the printed stenographic report? It is entirely possible that Stalin never said these words at the plenum but prepared them later for inclusion in the stenogram text.

His concluding remarks are also relevant to another puzzle of the June 1936 plenum. The most important item on the plenum’s agenda was never mentioned in any of the accounts of the meeting, and discussion of it was not recorded in any of the stenograms or reports. This ultrasecret transcript concerned the upcoming show trial of Zinoviev and Kamenev for treason.17 We suspect from subsequent accounts that Stalin spoke on this matter, possibly delivering a Politburo report on the question. He probably announced the upcoming trial and gave an overview of the charges against the accused, based on evidence that Yezhov had been gathering since the beginning of 1936. Moreover, the original version of the minutes notes that the plenum heard a “Communication” [soobshchenie] from NKVD chief Yagoda. Subsequent minutes from the February–March 1937 plenum refer to this Yagoda “report” to the June plenum and make it clear that he spoke about the upcoming show trial of Zinoviev and Kamenev.18

The June 1936 plenum presents us with a series of contrasts and apparent contradictions. The leadership denounced careless mass expulsions from the party and encouraged speedy appeals and readmissions. But it also announced the beginning of organized terror against former members of the opposition. Stalin implicitly criticized Yezhov for excessive expulsions but promoted him to head the terror less than three months later.

There was no real contradiction between Stalin’s condemnation of the party membership purges and his launching of terror against Old Bolsheviks. The former had been carried out by members of the nomenklatura, while the latter would be directed against it, even enlisting the support of the rank-and-file victims of the screenings. No one at the time thought that the recently completed screenings had anything to do with the purge trials.

Stalin once again revealed himself to be a master of compromise, balance, and political maneuver inside and outside the nomenklatura. No one knew exactly where he stood, and no one (including, perhaps, Stalin himself) knew exactly where events were leading. Regional officials were criticized strongly, but the affair was hidden from the party masses and no one from that group was punished: Postyshev was raked over the coals but retained his position and rank. The regional secretaries’ sins were deliberately hidden from rank-and-file anger, but enough was leaked to suggest to party members that all might not be quite right with their immediate superiors.

Despite the severe attacks on regional party leaders, when all was said and done, Stalin, Molotov, Postyshev, and the network of regional secretaries were all members of the same club, the nomenklatura. While they might thrash each other in the private confines of the Central Committee, such intragroup conflicts had to be muted or hidden from the public. Serious discord must be hidden so as not to disturb “the smooth surface of euphemized power.”19 Thus the public transcript only vaguely hinted that unnamed, low-level party functionaries had made “mistakes.” Nevertheless, Stalin could, in the interests of party unity before the public, simply have kept the entire episode out of the public view. By even hinting in the public press that there was a shadow of some kind over the regional secretaries, Stalin and his circle were able to hold a kind of sword over these officials: they were not entirely immune from censure and disclosure of their sins.

These textual variations show more than mere censorship of secret party meetings. They illustrate alternative political transcripts, constructed realities, that presented different versions of politics to different audiences. The public received a hazy general picture that nevertheless communicated something significant: some unnamed individual party secretaries had made mistakes, but the senior leadership was united, Stalin and Yezhov were attending to the problems. To insiders, the problem of wrongful expulsions was portrayed as being more serious. Stalin had personally intervened (textually if not orally) and had been more critical of the party secretaries and, implicitly, of Yezhov. To those in the senior nomenklatura and the Central Committee, Stalin had been sharply critical of the entire screening process, suggesting that the process had targeted the wrong people. A senior nomenklaturchik, Postyshev, had been directly attacked.

Finally, it is interesting that Stalin chose to reveal anything of the conflicts outside the top leadership. Attentive readers of even the laconic public versions must have noted something in the way of disharmony. Why, for example, was Stalin’s intervention necessary at all? Similarly, party members also received clues about possible discord in the top ranks. It may well be that Stalin decided to leak these tidbits as a way of chastising the nomenklatura by suggesting to its members that in the future, the solid facade of elite unity was not necessarily obligatory, and their public image would depend on their conduct.

G. M. Malenkov

Top left: From left, L. M. Kaganovich, I. V. Stalin, V. M. Molotov, 1920s

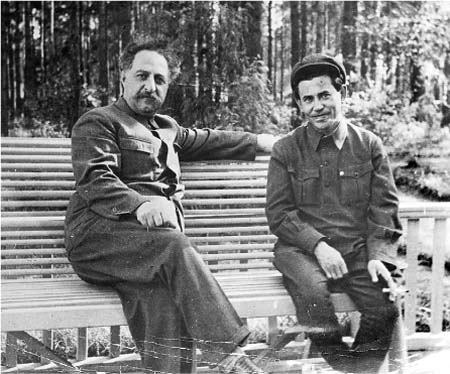

Bottom left: G. K. Ordzhonikidze, left, and N. I. Yezhov

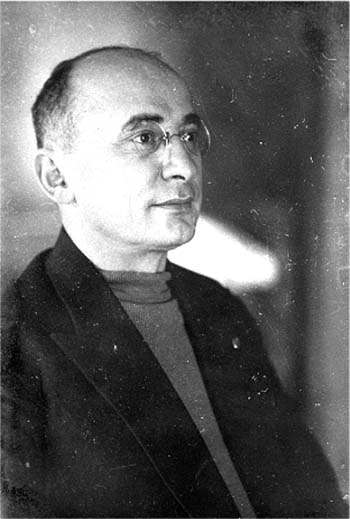

Above: L. P. Beria

P. P. Postyshev

M. N. Riutin

N. K. Krupskaia