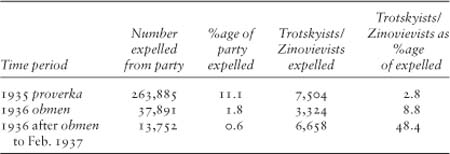

Table 4

Expulsion of “Oppositionists,” 1935–36

Source: RTsKhIDNI f. 17. op. 120, d. 278, ll. 2–3.

The interests of the Revolution demand that we put an immediate end to the activities of this gang of rabid murderers, agents of fascism. —Azov–Black Sea Party committee resolution, 1936

Surely, things will go smoothly with Yezhov at the helm.—L. M. Kaganovich to G. K. Ordzhonikidze, 1936

IN THE FIRST DAYS of 1936 one Valentin Olberg, a former associate of Trotsky, was arrested by the NKVD in the city of Gorky, apparently in connection with his suspicious history of foreign travel.1 Under interrogation, he admitted to being Trotsky’s “emissary” who had carried news to the exiled leader and “instructions” from him back into the USSR. This “information,” along with reports from NKVD informers about other couriers, was passed to Stalin in the Central Committee. Stalin decided to reopen the Kirov investigation. According to Yezhov’s later account, “Stalin, correctly sensing in all this something not quite right, gave instructions to continue [the investigation] and, in particular, to send me from the Central Committee to oversee the investigation.”2

Extracting confessions, no doubt under pressure, from successive interrogations, NKVD investigators working for Yagoda but under Yezhov’s supervision expanded the circle of the “conspiracy,” and by spring they had arrested several important former Trotskyists. Yezhov, eager to make a case and a name for himself, used his mandate from Stalin to expand the circle of arrests. By late spring he had elaborated a conspiracy theory in which Zinoviev and Kamenev, acting under instructions from Trotsky in exile, had directly and personally plotted the assassination of Kirov, Stalin, and other members of the Politburo. Effectively, then, Stalin had reopened the investigation into the Kirov assassination more than a year after it had been pronounced closed and several months after Yezhov’s failed attempt to reopen it in June 1935. Zinoviev and Kamenev, who had been in prison since early 1935, were reinterrogated.

Yagoda had been under a cloud since early 1935. After all, the “negligence” of his NKVD had permitted Kirov’s assassin to get close enough to fire the shot. We have also seen that the Kremlin Affair of mid-1935 was pointedly “uncovered” by Yezhov and party organs, rather than by the NKVD, whose job it should have been. Now, in the first half of 1936, Yagoda was being undermined by Yezhov again. Subsequent accusations in 1937 suggested that during Yezhov’s 1936 “supervision” of the investigation, Yagoda and his deputy Molchanov had downplayed the importance of the Trotsky-Zinoviev connection and had tried to deflect or limit Yezhov’s efforts. At one point, Yagoda had called the evidence that Trotsky was ordering terrorism in the USSR “trifles” and “nonsense” (chepukha, erunda). At another point, Stalin telephoned Yagoda and threatened to “punch him in the nose” if he continued to drag his feet.3

No doubt in response to this pressure, Yagoda now proposed drastic measures against Trotskyists—even those already in prison—in a 25 March 1936 memorandum to Stalin. As means of “liquidating the Trotskyist underground,” Yagoda proposed summary death sentences for any Trotskyists suspected of “terrorist activity.” Stalin referred Yagoda’s memo to Vyshinsky for a legal opinion; the procurator replied, “From my point of view, there is no objection to transferring the cases of Trotskyists whose guilt in terrorist activities had been established, that is, of preparing terrorist acts, to the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court with application of the law of 1 December 1934 and the highest means of punishment—shooting.”4

After this, the roundup and persecution intensified. Five hundred eight Trotskyists were under arrest by April 1936. In May the Politburo ordered all Trotskyists in exile and those formerly expelled from the party for “enemy activity” to be sent to remote camps for three to five years. Those convicted of participation in “terror” were to be retried and executed.5 By July, Yezhov had secured confessions from a number of former Trotskyist leaders, as well as from Zinoviev and Kamenev. There are persistent rumors that Zinoviev and Kamenev agreed to confess to the scenario in return for promises that their lives would be spared, but no documentary evidence or firsthand testimony has been found to support this story.6Others argue that they may have confessed out of loyalty to the party, which needed their confessions as negative examples.7 This explanation of the confessions of Old Bolsheviks in the show trials of the 1930s is supported by Bukharin’s last letter to Stalin from prison. And, as Zinoviev wrote in prison in a manuscript called “Deserved Sentence,” “Whoever plays with the idea of ‘opposition’ to the socialist state plays with the idea of counterrevolutionary terror…. Be born again as a Bolshevik! Finish your human days conscious of your guilt before the Party! Do everything in order to erase this guilt.”8

The stage was now set for the first in a series of public treason trials of former oppositionists, announced to Central Committee members at the June 1936 plenum. Now it was time to inform a broader party audience, and in July 1936 the Central Committee sent an explanatory letter to party organizations. Written by Yezhov and edited by Stalin, the letter had to answer several questions that were bound to arise in connection with this announcement: Why did it take so long to discover the conspiracy, especially when the NKVD had closed the case in 1935? How could these Old Bolsheviks, who fought in the Revolution and Civil War, have conspired with evil forces to cede part of the country?9 Given the 1936 pendulum swing toward strong persecution of the opposition, it was necessary to amend the existing master narrative on the opposition leaders and to change the content of the Trotskyist trope. Recently discovered “new materials” were the explanation:

On the basis of new materials gathered by the NKVD in 1936, it can be considered an established fact that Zinoviev and Kamenev were not only the fomenters of terroristic activity against the leaders of our Party and government but also the authors of direct instructions regarding both the murder of S. M. Kirov as well as preparations for attempts on the lives of other leaders of our Party and, first and foremost, on the life of Comrade Stalin.10

The subsequent political trial could not have come as much of a surprise in the top party leadership. The supervision of the investigation from the beginning of the year by Yezhov, who had tried to make the case against Zinoviev and Kamenev at the June 1935 CC plenum, was widely known in the upper leadership. Stalin had discussed the upcoming repression with the Central Committee in June 1936, and the July letter was read out to all party organizations.11 The amended narrative could not have given NKVD chief Yagoda much comfort; his NKVD had uncovered the “new materials” only under Yezhov’s imposed and unwanted supervision.

Like other public accusations and show trials of this period, the 1936 trial scenario was based on a kernel of truth that had been embellished and exaggerated. We know that in the fall of 1932 a single bloc of oppositionists uniting Trotskyists and Zinovievists had in fact been formed at Trotsky’s initiative.12 But there is no evidence that this bloc was oriented toward organizing “terrorist acts” or anything other than political conspiracy. In the hands of the Stalinists, though, this event was magnified into a terrorist conspiracy aimed at killing the Soviet leaders.

From 19 to 24 August 1936, Zinoviev, Kamenev, I. N. Smirnov, and thirteen other former oppositionists were tried in Moscow for treason. With the exception of Smirnov, who retracted his confession, all of the accused admitted to having organized a “terrorist center” at Trotsky’s instructions and to have planned the assassinations of Kirov, Stalin, Kaganovich, and other members of the Politburo. As with all the major show trials, Yagoda, Yezhov, and Vyshinsky assembled the scenario, but Stalin played an active role in rewording the indictment, selecting the final slate of defendants, and prescribing the sentences.13 The death sentences meted out to the defendants (as with all death sentences in political cases for years before) were decided beforehand by the Politburo.14 Altogether throughout 1936, 160 persons were arrested and shot in connection with “terrorist conspiracies” related to this trial.15

The first show trial of the opposition sent a strong signal through the ranks of the nomenklatura and the party in general: former leftist oppositionists could no longer be automatically trusted to work loyally, even if they had recanted their views. Leaders of party organizations understood the signal and the required ritual. In line with directives from Moscow to mobilize support for the trial, they organized meetings of party members and ordinary citizens to produce supporting resolutions and letters. Such collective resolutions ostensibly came from below, but because of their solicitation and formulaic nature should be considered elements of central, public rhetoric designed to affirm the desired unanimity. As the loyal Bolsheviks of Makhachkala telegraphed to Stalin,

THE PARTY AKTIV OF MAKHACHKALA, HAVING DISCUSSED THE PROGRESS OF THE TRIAL OF THE TROTSKYIST-ZINOVIEVIST GANG, DEMANDS THAT THE SUPREME COURT EXECUTE THE THREE-TIME CONTEMPTIBLE DEGENERATES, WHO HAVE SLID INTO THE MIRE OF FASCISM AND AIMED THEIR GUNS AT THE HEART OF OUR PARTY, THE GREAT STALIN…. LONG LIVE THE GREAT LEADER OF ALL THE OPPRESSED AND ENSLAVED OF THE WORLD, OUR DEAR AND BELOVED STALIN! DEATH TO THE MURDERERS, TO THE TERRORISTS, TO THE VILE TRAITORS OF THE SOCIALIST MOTHERLAND!16

Thus the language surrounding the Zinoviev-Kamenev trial consisted of several parts. The CC’s July letter elaborated the discursive line; the prescribed letters and telegrams provided symbolic affirmation from below; the trial itself provided the ritual performance of the new line. This was a classic example of the mechanism for changing Stalinist policies; tropes were filled with new content. However, the fact that actors at the various levels played their roles does not mean that they did so insincerely or that they did not believe the new line. Obviously, the new transcript could not have been successful had it not filled particular needs or found resonance at various levels. It could not create reality from scratch; it could only adapt and redirect it.

The official face of the enemy was reconstructed in the summer of 1936: he was a former leftist oppositionist who had taken the path of terror. He was an agent of Trotsky, a spy, an assassin. This version had advantages for several segments of the party. For Stalin and his circle, it provided a rationale for finally destroying personal and political enemies whose opposition went back more than a decade, and it created a climate in which future opposition to him obviously carried life-and-death risks. For the nomenklatura at all levels, it justified the obliteration of and final victory over a possible alternative leadership whose leaders had argued for years that the Stalinist team should be removed. This definition—or attribution—of the enemy also benefited the ruling elite as a whole insofar as it presented a clearly defined evil and opposite “other”: the groups behind Zinoviev, Kamenev, and Trotsky. They had for years stood for an alternative team to lead the country. If they won, however unlikely that might seem, the current team would be replaced in quick order. Although there seemed little chance that Zinoviev or Trotsky would return to power in the mid-1930s, the possibility always existed. Nomenklatura members’ memories told them that stranger things had happened. Lenin’s ascension to power in 1917 must have seemed at least as far-fetched in 1915. This evil force could be conveniently blamed for a variety of sins of the moment, including industrial failure, agricultural shortfalls, and other policy shortcomings more properly attributable to the nomenklatura itself.17The leftist opposition made perfect scapegoats.

But they were scapegoats of a particularly believable kind, given the prevailing mentalities of the time. The 1917 revolutions, the Civil War, and party struggles of the 1920s had created a kind of conspiracy mentality among the Bolsheviks. The vicious and violent civil war, which was rich with real conspiracies and constant, nagging insecurity, was the formative experience for this generation of nomenklatura and party member. In their view of reality, politics was inconceivable without conspiracy, and it was not hard for them to believe that professional revolutionaries and skilled conspirators like Zinoviev and Trotsky probably had been up to no good on some level. Similarly, for the Russian populace, with its cultural legacies of good versus evil, belief in the machinations of dark forces of all kinds, and a traditional suspicion of educated intellectuals, it was not difficult to accept the notion that Jewish Bolshevik intellectuals probably were involved in some sort of dark business.

There seem to have been no protests or questions raised in party leadership circles about executing these former oppositionists. Part of the reason was fear; knowing that police investigations were continuing, who would question Stalin’s leadership on such a serious matter and risk being regarded as defenders of enemies? Another part of the answer was party discipline. In the crisis atmosphere of the times, which was perceived as a continuation of the “new situation” following the Riutin affair, there was strong incentive in the party to close ranks against the perceived threat.

The Zinoviev and Trotsky oppositions had broken the rules of the nomenklatura. In the 1920s (and as recently as the Riutin Platform) they had threatened to organize politically outside the party elite. Their strategy had been to agitate among the party’s rank and file to gain support for their platforms against the ruling group. This was the unpardonable sin. By threatening to split the party (a split that, since the Civil War, was the Bolsheviks’ worst nightmare), this strategy threatened the survival of the regime and thus of the Revolution.

At bottom, the strategy threatened to turn the membership against the ruling stratum. This could not be tolerated. The opposition therefore represented a continuing danger to the corporate interests of the Stalinist nomenklatura that outweighed any nostalgia leaders may have felt for their former Old Bolshevik oppositionist comrades-in-arms. The party elite did not regard the annihilation of Zinoviev and Kamenev as threatening to itself. It was not hard, then, for the current serving party leadership to support the final decimation of the leftist opposition. Once again, Stalin and the nomenklatura had common interests.

However useful it may have seemed to scapegoat the opposition and to identify officially approved enemies for public consumption, the tactic carried risks for the party elite. It was convenient for regional party secretaries to use a fluid definition of Trotskyism to marginalize, expel, and even arrest professional dissidents in their localities. On the other hand, an increasingly plastic definition of enemies and “Trotskyists” could be a loose cannon for the nomenklatura itself. The new rhetoric opened dangerous doors.

It was not only the serving members of the nomenklatura who could use the new accusatory narrative against its opponents. Ideological fanatics, careerists, opportunists, and ordinary party members with grudges to settle adopted the new line for their own purposes. In the aftermath of the July closed letter and the first trial, denunciations had increased at all levels.

Denunciations posed a new question: aside from marginalized has-beens like Zinoviev, were “Trotskyists” at work among serving officials in the state and party apparatus? The testimony of the Zinoviev trial had given a signal. Almost as an aside, some of the defendants had suggested conspiratorial links with long-recanted, apparently loyal ex-Trotskyists who were currently serving in the state apparatus. G. Piatakov, deputy commissar of Heavy Industry, and the prominent journalist Karl Radek had sided with the Trotskyist opposition in the 1920s. Although they had forsworn Trotskyism early in the 1930s, they were implicated in the trial testimony, as were rightist leaders Bukharin, Rykov, and Tomsky. Could it be that even high-ranking captains of industry with ancient Trotskyist connections were guilty of treason? Evidently, Stalin had authorized Yezhov to root out all former active Trotskyists and Zinovievists; to follow the trail of their personal connections wherever it led. And since such people with politically compromised pasts were working in the apparatus, the path of investigations began to wind itself into the bureaucracy. Regional leaders of the nomenklatura picked up on the increasingly ambiguous definition of the enemy’s face.

What had seemed a useful definition of the enemy was mutating in dangerous ways. If captains of industry with compromising pasts were at risk, what about their own subordinates with or without similarly blemished political records? Although the regional secretaries were obliged to promulgate the new ideological transcript, it could have given them no pleasure to incorporate into their resolutions the notion that their own machines needed to be “checked and re-checked.”

This checking and rechecking would by early 1937 result in the removal and sometimes arrest of a number of lower-level party officials in the provinces. By that time, according to data provided by chief of the Central Committee’s party registration sector, G. M. Malenkov, some thirty-five hundred party members across the USSR had been removed from office as “enemies,” representing about 3.5 percent of all those checked.18

Beginning in the fall of 1936, criticism of these officials escalated as the hunt for Trotskyists expanded. But in late 1936 through the first half of 1937, no regional party secretary was accused of disloyalty or association with “enemy conspiracies.” In the fall of 1936 the only implication was that some had been lax in keeping their own political houses in order, and as late as the February–March 1937 plenum of the Central Committee, Stalin would go out of his way to publicly absolve them, arguing that they were by no means “bad” in this regard.19

On the other hand, it is possible to see in these moves the first step in a devious Stalin plan to destroy the provincial party leaders and apparatus. Several months later, in the second half of 1937, he would do just that. One could thus explain the new political line of late 1936 as the first tactical step in weakening the regional leaders preparatory to finishing them off later. The apparent restraint by Stalin at this point may have been part of a cat-and-mouse game. Or it may have been a means of threatening the regional leaders while at the same time giving them a clean bill of political health in order to secure their support in the upcoming move to destroy Bukharin, the military, or others.

But Stalin could simply arrest and remove regional leaders individually or en masse at any time, and it is hard to see what he would have gained by playing cat-and-mouse with them. Stalin did not need to entice or encourage the regional secretaries to support a move against Bukharin. Experience had shown that they were perfectly willing to take the lead in condemning former oppositionists without much encouragement. In other words, if at this time he planned to destroy them, he had nothing to gain by waiting, a tactic that would also carry a certain risk.

A possible plan to destroy the regional nomenklatura is not necessary to explain Stalin’s criticism and political text about political carelessness in the party apparatus. In its own right, such criticism was a useful tool that Stalin could use to control and discipline regional leaders. Party secretaries, as we have seen, were powerful satraps in their territories, dominating the legal, police, cultural, ideological, and everyday lives of the population. Many of them were petty tyrants, operating their own regional and local personality cults.

In Azerbaijan, progress in the oil industry was attributed to the wise guidance of the party first secretary in Baku. Stalin had observed that in the Caucasus there was not one real party committee but rather rule based on the will of individual party chieftains (he used the Cossack term ataman). In Ukraine an authoritative text on literature noted that the development of Ukrainian and Russian literature was in considerable measure due to the opinions of the party secretary in Kiev. One issue of a local newspaper mentioned the first secretary’s name sixty times. (The fact that the secretary’s wife ran the ideological institute no doubt helped.) The first secretary of the Western Region, whose photograph frequently adorned the regional newspaper, was “the best Bolshevik in the region.” In Kazakhstan the republican party politburo even tried to rename the highest peak in the Tien Shan mountain range after the first secretary.20

From Moscow’s point of view, this situation was profoundly troubling and required considerable subtlety. On the one hand, Stalin needed these satraps to carry out Moscow’s policies in the far-flung regions of the country. It had been necessary to vest them with tremendous authority to implement collectivization and industrialization. They were Moscow’s only presence in the countryside and thus indispensable to the party. On the other hand, their near-absolute powers had permitted them to use patronage to create their own political machines: miniature nomenklaturas under their personal control, complete with regional personality cults.

Often, as Yezhov admitted in 1935, Moscow did not even know the identities of many local party leaders who staffed the regional machines.21Appointment of district party secretaries had been subject to Central Committee confirmation only since early 1935. Even by early 1937 the list of party officials subject to Central Committee confirmation (the list known as the Central Committee nomenklatura) included only 5,860 officials of a the national stratum of party secretaries and officials numbering well over 100,000.22 In the mid-thirties, squabbles between regional leaders and the Central Committee secretariat about the appointment of this or that person were common and involved continuous negotiation. Generally, though, the regional party secretaries could prevail, if they pushed the point hard enough, and were thus able to staff their machines with “their people” more often than not.

How, then, could Moscow control the activities of the provincial governors? Stalin created various parallel hierarchies and channels of information (the NKVD and Party Control Commission were examples), but experience showed that even these nominally independent institutions sooner or later came under local machine control.23

Another tactic which Stalin frequently used was “control from below,” a policy that he would discuss at some length at the upcoming February–March plenum of the Central Committee.24 The often arbitrary rule of regional leaders created resentment from below, and it was possible for Stalin to encourage criticism of the party apparatus from those quarters. Of course, it was in the interests of neither Stalin nor the nomenklatura to permit a full and open discussion of the problem of government, so this discourse had to be kept within strict limits. The real reasons for local misconduct, dysfunctional administration, and corresponding popular resentment could not be discussed; things could not be named by their names. A genuine analysis of administrative problems would include discussion of the dictatorship itself and would threaten the governing myths of the regime. Such a discussion would touch on the lack of national consensus on Bolshevik dictatorship, the undemocratic selection of leaders at all levels, the constant recourse to terror as a substitute for consensual government, and the shifting voluntarist policy mistakes that characterized Bolshevik rule.25

The trick, then, for Stalin, and the essence of “control from below” was to encourage rank-and-file criticism of the middle-level leaders on particular issues of nonfulfillment or negligence. In this way, Stalin could receive specific information from the grass roots that bypassed the nomenklatura’s normal information filters. He could solicit grassroots information and input about official misconduct, suspicious characters in high positions, and the nonfulfillment of decisions. Moreover, he could play the role of the good tsar, posing as a caring and attentive friend of the little guy against the highhanded actions of the “feudal princes,” as he had called the regional secretaries at the 1934 party congress. It was desirable to use the rank and file as a stick over the heads of the midlevel apparatus without inciting riot from below. Because of the power of the local party leaders, such criticism could not happen without high-level license and approval.

The new public rhetoric about nomenklatura “political laxity” provided a vehicle for underlings to criticize the regional party elite around the country. As such, it emphasized the long-standing tension between leaders and led. This policy walked a fine line; it was desirable to blame (and thereby control) the middle party apparatus for the sins of the regime without destroying them completely. Stalin wanted to hold the regional secretaries’ feet to the fire without setting the whole house ablaze. In his speech to the February–March plenum, he pointed out that although the regional party officials were not themselves bad, the rank-and-file members often knew better than they who was suspicious and who was not.26

As the continuing hunt for Trotskyists spread into the level of serving officials, it disturbed the leaders of the party apparatus. They gave up some of their valued assistants with dubious pasts when they had to, but they also used their power to try to limit the application of the “Trotskyist” label and to protect their own. Courts and procurators controlled by the local party machines frequently adopted a narrow definition of Trotskyism (and the criminality associated with it).

Central organs often complained about the practice. The easiest thing to do to deflect the heat was to expel large numbers of rank-and-file party members for suspicious pasts, speech, or connections. But Moscow was wise to this and had outlawed the practice. The next-most-expendable group comprised economic and technical specialists who worked for Moscow-based ministries rather than for the local party machine. At the beginning of 1937, however, the CC noted that several regional party secretaries,

wishing to avoid reprimand, were very freely giving permission to the NKVD to arrest directors, technical directors, engineers, technicians and construction specialists in industry, transport and other economic branches. The CC reminds you that provincial party secretaries, much less local party officials, do not have the right to give permission for such arrests. The CC obliges you to follow the rules, obligatory for both party and NKVD, according to which arrests of [such specialists] can be carried out only with the agreement of the relevant ministry.27

There were several competing definitions of Trotskyism. Traditionally, Trotskyists were those who had formally or openly participated in the leftist opposition (from 1923 as Trotskyists or from 1926 as “United Oppositionists,” together with the Zinoviev group). By the early 1930s the definition was expanded to include those who might at some time have voted for a Trotskyist platform at a party meeting or defended a known Trotskyist from party punishment. Such actions were considered “incompatible with party membership” and had resulted in expulsion from the party. Trotskyism, although a party crime, was not a punishable offense under the state’s criminal code. It was therefore necessary to use extralegal bodies like the NKVD’s Special Conference to punish oppositionists, often by exile. In the course of 1936, however, both the definition of Trotskyism and the prescribed sanctions against it became much more severe. Already in the summer of 1936, Trotskyists suspected of “terrorism” were being executed. The Zinoviev trial made this new line public: some oppositionists were said to have crossed the line from political dissidence to treasonable criminal activity. But not all elements in the party-state hierarchy were eager to apply the new standard.

On 29 September 1936 the Politburo made a firm statement on the matter. Trotskyists were no longer to be considered to be polemical opponents on the left; now, as a category, they were defined as fascist spies and saboteurs. This document provides an excellent example not only of attributive definition of enemies, but also of explicit and self-conscious narrative construction through a prescriptive text. The political-linguistic process of attribution was quite open: a “directive” defined “our stance” on certain groups who “must now therefore be considered” in a different way. The form of the enemy was now filled with new content.

a) Until very recently, the CC of the VKP(b) considered the Trotskyist-Zinovievist scoundrels as the leading political and organizational detachment of the international bourgeoisie. The latest facts tell us that these gentlemen have slid even deeper [into the mire]. They must therefore now be considered as foreign agents, spies, subversives and wreckers representing the fascist bourgeoisie of Europe.

b) In connection with this, it is necessary for us to make short shrift of these Trotskyist-Zinovievist scoundrels. This is to include not only those who have been arrested and whose investigation has already been completed … but also those who had been exiled earlier.28

For everybody, the dramatic and disorienting social changes taking place in the country since 1929, the disastrous famine of the early 1930s, the incomprehensible economic system with its unpredictable “mistakes” and lurches back and forth all cried out for simplistic explanations. From peasant to Politburo member, the language about evil conspirators served a purpose. For the plebeians it provided a possible explanation for the daily chaos and misery of life. For the many committed enthusiasts it explained why their Herculean efforts to build socialism often produced bad results. For the nomenklatura member, it was an excuse to destroy their only challengers. For local party chiefs, it was a rationale for again expelling inconvenient people from the local machines. For the Politburo member, it provided a means to avoid self-questioning about party policy and a vehicle for closing ranks. The image of evil, conspiring Trotskyists was convenient for everybody.29 The question, of course, was who was the evil force.

After receipt of the July letter and before the trial itself began, local secretaries ordered the party membership to be screened again for anyone who had had any connection in the past with Zinovievist or Trotskyist groups.30 Over the next several months, thousands were expelled from the party for present and past suspicious activities. Meetings were held, files were scanned again, and memories wracked to uncover any possible former connection to the leftist opposition. In the climate following the trial, the definition of Trotskyism became quite fluid; it could include a careless remark decades before, an abstention in the early 1920s on some resolution against Trotsky, or a perceived lack of faith in the party line at any time.

Table 4 shows the quantitative dimension of these expulsions in comparison with those of the recently completed party screenings. Numerically, the attrition of this round of purges was smaller than the verification and exchange of documents; only about one half of one percent of the party was expelled. Although explicitly named Trotskyists and Zinovievists had constituted a small fraction of those expelled earlier, they made up nearly half of those removed in the new campaign. There was, however, one similarity between this round of expulsions and the previous operations. In both cases, local and regional party secretaries were again able to serve their own ends. They were again able to direct the fire downward; the vast majority of victims of these expulsions were again rank-and-file party members.

Table 4

Expulsion of “Oppositionists,” 1935–36

Source: RTsKhIDNI f. 17. op. 120, d. 278, ll. 2–3.

The Kirov and Yenukidze cases had called NKVD chief Yagoda’s competence into question. Although Yagoda said that he had always considered the followers of Zinoviev, Kamenev, and Trotsky to be guilty and had participated in the trials and repressions of them until the fall of 1936, since the attack on Yenukidze in mid-1935, it always seemed to be the party, not the NKVD, that uncovered the various plots and conspiracies.31 Behind the scenes, Yagoda’s credibility and leadership of the secret police became more questionable in 1936 as Yezhov, with Stalin’s support, became curator of the NKVD’s investigations of the opposition. Materials in Yezhov’s archive show that he angled for Yagoda’s job, never missing an opportunity to criticize the NKVD chief to Stalin. As a skilled bureaucratic player, Yezhov used bureaucratic “weapons of the weak” to manipulate his boss whenever possible.32

Moreover, when the former rightist Mikhail Tomsky committed suicide in August 1936, he left behind a letter hinting that Yagoda had been the one to recruit him into the Right Opposition back in 1928. Yezhov investigated the accusation, and while he reported to Stalin that Tomsky’s charge against Yagoda lacked credibility, he nevertheless noted that “so many deficiencies have been uncovered in the work of the NKVD that it is impossible to tolerate them further.”33 Given Yezhov’s relentless campaign, it is perhaps surprising that Yagoda held on as long as he did.

Yezhov used the middle months of 1936 to co-opt several of Yagoda’s key deputies, including Frinovsky, Zakovsky, and the Berman brothers, against the Yagoda loyalists Molchanov and Prokofiev. Deputy NKVD Commissar Agranov seems to have tried to play each side against the other. In September 1936 the other shoe dropped and Yagoda was removed. From their vacation site at Sochi, Stalin and A. A. Zhdanov sent a telegram to the Politburo calling for Yagoda’s replacement by Yezhov, claiming that under Yagoda the NKVD was “four years behind” in investigating the leftist opposition.34

It is difficult to know the immediate catalyst for this decision. Perhaps the dramatic explosions in the mines of Kemerovo three days earlier (which would soon be characterized as Trotskyist sabotage) cast further doubt on Yagoda’s security measures. It is also possible that the arrest of G. Piatakov, deputy commissar for heavy industry, was related to Yagoda’s fall. The arrest of Piatakov in mid-September raised the temperature considerably: Piatakov was an important, currently serving official whose arrest occasioned protests from Sergo Ordzhonikidze and perhaps others. The coincidence in time between Piatakov’s arrest and Yagoda’s removal may suggest that Yagoda had put his foot down against arrests within the office-holding bureaucracy. Or perhaps Yagoda’s fall had been discussed by the Politburo in advance; we cannot know for certain. At any rate, Stalin’s proposal was approved without a Politburo meeting (by polling the members [oprosom]), and not formally ratified until 11 October 1936. Even then, Yagoda’s fate was not clear. Transferred to the “reserve list,” he was appointed commissar of communications and remained a member of the Central Committee and at liberty for six months.

Yagoda had not been a popular figure, but Yezhov was regarded as a conscientious and loyal party worker, and his appointment did not cause any special alarm in party circles. Even Bukharin “got along very well” with Yezhov, considered him an “honest person,” and welcomed the appointment.35 Most Politburo members were on vacation at the time of Yezhov’s appointment, and L. M. Kaganovich, who remained on duty for the Politburo in Moscow, wrote to his friend Ordzhonikidze (commissar for heavy industry) with the news. By this time, several of Orzhonikidze’s assistants, department heads, and plant managers with “suspicious” pasts were already under investigation. Kaganovich’s letter sought to reassure Ordzhonikidze that the appointment was a good one. “My dear, dear Sergo, how are you? First of all, I hope you are not angry with me for not writing to you for so long. The OGPU has been years behind schedule in this matter. It failed to forestall the vile murder of Kirov. Surely, things will go smoothly with Yezhov at the helm.”36

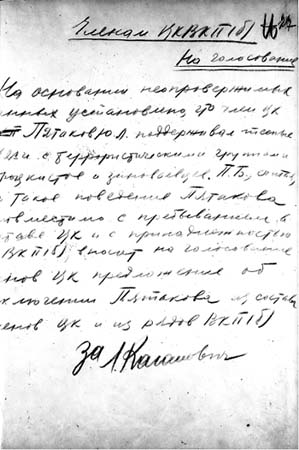

Letter from Kaganovich to Ordzhonikidze applauding Yezhov’s appointment as head of the NKVD. 30 September 1936

Yezhov’s new appointment occasioned several developments. First, he set about replacing Yagoda’s people in the apparatus of the NKVD with “new men.” These new recruits, brought in to “strengthen” and rebuild the staff of the NKVD, were largely taken from the party apparatus and from party political training schools; the Orgburo was kept busy processing these appointments.37 In these weeks, the Politburo ratified numerous lists of “mobilizations” of party workers for service in the NKVD. Yezhov would later brag that he had purged fourteen thousand chekists from the NKVD. Yagoda’s fall and Yezhov’s appointment at NKVD coincided with the extension of serious proceedings against ex-Trotskyists and other “suspicious persons” wherever they could be found. The July letter announcing the upcoming Zinoviev trial had claimed that terrorists had been able to embezzle state funds to support their activities. As early as summer 1936 G. I. Malenkov (head of the membership registration sector of the Central Committee and a close collaborator with Yezhov) had ordered his deputies to check the party files of several hundred responsible officials in economic administration for signs of suspicious activity in their pasts. In one such check, the files of 2,150 “leading personnel in industry and transport” turned up “compromising material” (defined not only as previous adherence to oppositional groups but also as party reprimands or membership in other political parties) on 526 officials. At that time, though, only 50 of them were removed from their positions.38

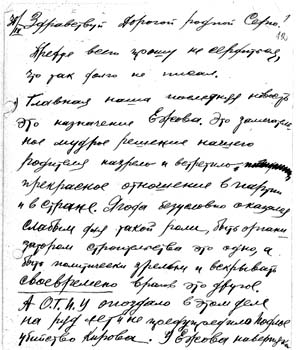

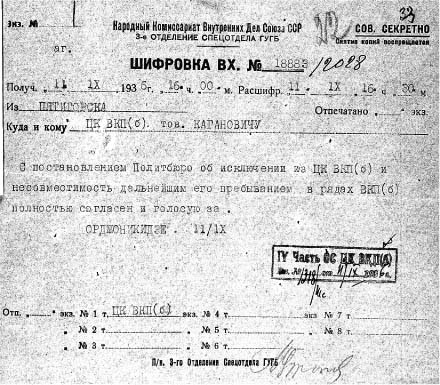

Piatakov’s telegram to Stalin voting to expel Sokolnikov from the party. 27 July 1936

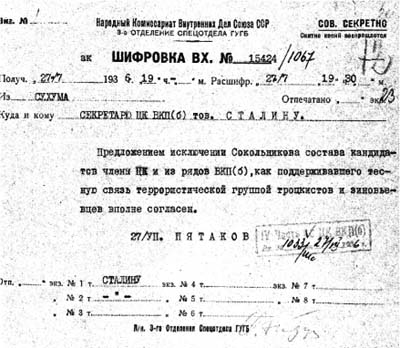

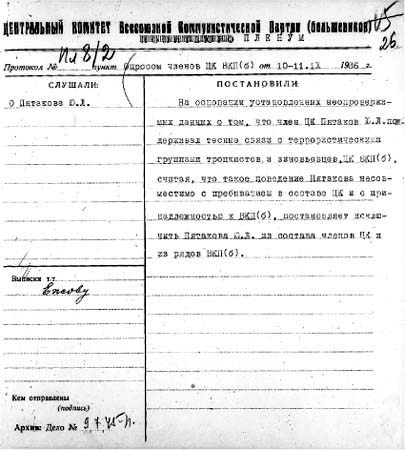

Kaganovich’s first draft of Politburo resolution to expel G. Piatakov from the party. 10 September 1936

Politburo resolution expelling G. Piatakov from the party. 10–11 September 1936

From the fall of 1936 the NKVD began to arrest economic officials, mostly of low rank, ostensibly in connection with various incidents of industrial sabotage. By the beginning of 1937 nearly a thousand persons working in economic commissariats were under arrest.39 The real bombshell, however, came in mid-September when Deputy Commissar of Heavy Industry Piatakov was arrested. Piatakov, a well-known former Trotskyist, had been under a cloud at least since July, when an NKVD raid on the apartment of his ex-wife turned up compromising materials on his Trotskyist activities ten years earlier. In August, Yezhov interviewed him and told him that he was being transferred to a position as head of a construction project. Piatakov protested his innocence, claiming that his only sin was in not seeing the counterrevolutionary activities of his wife. He offered to testify against Zinoviev and Kamenev and even volunteered to execute them personally, along with his ex-wife. (Yezhov declined the offer as “absurd.”) During August, Piatakov wrote both to Stalin and Ordzhonikidze, protesting his innocence and referring to Zinoviev, Kamenev, and Trotsky as “rotten” and “base.”40 None of this did him any good. He was expelled from the party on 11 September and arrested the next day.

Telegram from Sergo Ordzhonikidze to Kaganovich voting to expel Ordzhonikidze’s deputy G. Piatakov from the party. 11 September 1936

As Sergo Ordzhonikidze’s deputy at Heavy Industry, Piatakov was an important official with overall supervision over mining, chemicals, and other industrial operations. His arrest for sabotage and “terrorism” sent shock waves through the industrial establishment. Ordzhonikidze is said to have tried to intercede with Stalin to secure Piatakov’s freedom, and he had been successful in protecting lower-level industrial cadres from NKVD harassment.41 This time, though, Stalin and Yezhov forwarded to him transcripts of Piatakov’s interrogations in which the latter gradually confessed to economic “wrecking,” sabotage, and collaboration with Zinoviev and Trotsky in a monstrous plot to overthrow the Bolshevik regime.42 According to Bukharin, who was present, Ordzhonikidze was invited to a “confrontation” with the arrested Piatakov, where he asked his deputy whether his confessions were coerced or voluntary. Piatakov answered that they were completely voluntary.43

There are no documents attesting to Ordzhonikidze’s protest. Aside from the account of his attendance at Piatakov’s confrontation, we have only a couple of oblique references by Stalin and Molotov at the next plenum (February–March 1937) that Ordzhonikidze had been slow to recognize the guilt of some enemies. But there is no evidence that his intervention took the form of protest against the use of terror against party enemies; he was by no means a “liberal” in such matters. Ordzhonikidze, as far as we know, never complained about the measures against Zinoviev, Kamenev, Trotsky, Bukharin, Rykov, Tomsky, or any other oppositionist per se. His defense of “enemies” was a bureaucrat’s defense of “his people,” with whom he worked and whom he needed to make his organization function. From his point of view, Yezhov’s depredations were improper only when they intruded into Ordzhonikidze’s bailiwick, when they threatened the smooth fulfillment of the economic plans his organization answered for, and when they infringed on his circle of clients. As a card-carrying member of the upper nomenklatura, Ordzhonikidze was not against using terror against the elite’s enemies, but he did fight to protect the patronage rights that he enjoyed as a member of that stratum.

In the case of another client, Ordzhonikidze had tried to shield the former dissident Lominadze from arrest, telling Stalin that he (Ordzhonikidze) could bring Lominadze around to a loyal position. But when Ordzhonikidze became convinced that Lominadze was a lost cause, he proposed having him shot, a solution that was at the time too radical even for Stalin.44

The procedure by which Piatakov was expelled from the party illustrates the themes of strong party discipline and nomenklatura solidarity. It also graphically shows the consequences of that solidarity when the elite began to commit suicide. Upon motions to expel a member of the Central Committee, members and candidates unanimously voted yes. (An occasional exception was Lenin’s widow Krupskaia, who on occasion voted “agreed” to the expulsion motion, rather than the more positive “yes” [za].)45 There were no dissidents, no arguments. Nomenklatura discipline overrode all other considerations. Piatakov voted to expel Sokolnikov, then was himself expelled. Zhukov voted (rather fiercely) to expel Piatakov, then was himself expelled a few months later.46

Even Ordzhonikidze, who privately complained about Piatakov’s detention, defended the leadership’s line and voted for his expulsion and subsequent arrest.47 Regardless of his doubts, he defended the notion of Piatakov’s guilt to his deputies at Heavy Industry and chastised them for failing to uncover the work of saboteurs.48

By the autumn of 1936 the widening circle of arrests was claiming more and more victims. Those arrested or expelled from the party, or their relatives, frequently appealed to high-ranking leaders for help and intercession. Often these requests were ignored. Other times, however, a Politburo member would intercede and use his personal power to save an acquaintance. Such petitions for intercession were part of a long Russian tradition of appeal to tsars for help and are a special category of personal-political text. In this case, the author used apologetic discourse, paying his “symbolic taxes” by confessing his errors to a powerful figure. In so doing, despite his complaints about injustice, the author implicitly affirmed the terms and rules of the system. I. Moiseev-Yershistyi, who had been expelled from the party, wrote to Molotov:

My dear and precious Viacheslav Mikhailovich! Having suffered an exceptionally grave tragedy in my Party life, I have taken the liberty to turn to you once again with a deep, heartfelt request to help me and my young children. Please don’t let me sink into a life of shame and scorn.

My dear, precious, beloved Viacheslav Mikhailovich, I know that our Party is so great, so mighty that the purity of its Leninist-Stalinist ideas is more exalted than anything else on earth, that it is the highest law of life. For that reason, my dear, beloved Viacheslav Mikhailovich, the greatest disciple of Lenin, who was a man of genius, I swear to you, the first and greatest assistant and loyal Comrade in Arms of the Great Stalin, to You, my dear, beloved Viacheslav Mikhailovich, I swear with all that’s left of my life, I swear by the young lives of my beloved children that I will never violate this exalted law of the Party. I swear to you that I would gladly wipe away my crime with my own blood at the Party’s call at any moment.

I. Moiseev (Yershistyi)

Two sets of instructions are appended to the letter:

To Comrade Yezhov: Moiseev-Yershistyi could hardly be troublesome to anybody in Leningrad. I doubt that he was justifiably expelled from the VKP(b).

9 September 1936. V. Molotov.

Inquire[d] with Shkiriatov. We have agreed to keep him in Leningrad and not to expel him from the Party. Let [the proper authorities in Leningrad] know about this.

Yezhov.49

The following letter was written by Mikhail Tomsky’s widow to Yezhov following her husband’s suicide. No record of an answer has been found in the archives.

Please help me find a job. I cannot live without work. Sometimes I feel that I am going crazy. I can no longer go on living cut off from life.

I have worked for a long time in the field of public catering and was a member of the Presidium of the Committee on Public Catering. I have also done administrative-economic work. I know how to work.

My eyes are hurting me now (the blood vessels in the pupils of both my eyes have burst), and I can read and write only for short periods of time. Perhaps it will all pass….

I apologize for the length of this letter, but it’s difficult to write more briefly.

My greetings.

M. Tomskaia50

From the dock of the August 1936 show trial, Kamenev had mentioned in his testimony the names of former rightist leaders Bukharin, Rykov, and Tomsky. At the close of the court session, Procurator Vyshinsky announced that he was opening an official investigation of the trio’s possible complicity with the accused. Even before this, the denunciations of the leftists had begun to rub off on Bukharin. On the eve of the trial, in the wake of the Closed Letter of July, denunciations of Bukharin and other rightists had begun to flow in to the Central Committee. Thus I. Kuchkin wrote a note to Yezhov: “I would like to call your attention to the following: Comrade N. I. Bukharin has been traveling to Leningrad frequently. While there, he has been staying at the apartment of Busygin, a former Trotskyist and now a counter-revolutionary.”51

Bukharin had been on vacation, mountain climbing in the Pamirs, when his name was mentioned at the Zinoviev trial. He rushed back to Moscow to defend himself, quickly writing a letter to Stalin protesting his innocence and demanding a confrontation with those arrested who had given evidence against him. Yezhov had meanwhile been busy trying to build a case against Bukharin. The key was G. I. Sokolnikov, a former oppositionist who had been arrested a month before the Zinoviev trial. In the course of his interrogation, Sokolnikov had apparently admitted not only his own close connections with the Zinovievists and Trotskyists but some complicity on Bukharin’s part. Following Sokolnikov’s testimony, Yezhov wrote to Stalin that in his opinion the rightists were involved in conspiracy, and asking permission to pursue the matter by reinterrogating several former Right Oppositionists. Stalin agreed. The results of these inquiries, combined with Sokolnikov’s statement, were apparently the basis for the public mention of Bukharin at Zinoviev’s trial.52

On 8 September, Bukharin and Rykov were granted a confrontation with the arrested Sokolnikov at Central Committee headquarters in the presence of a Politburo commission consisting of Kaganovich, Yezhov, and Vyshinsky. At that meeting Bukharin and Rykov denied any guilt and were permitted to question Sokolnikov. Sokolnikov stated that he had no personal knowledge of Bukharin’s or Rykov’s guilt. Sokolnikov’s only information was that Kamenev had told him back in 1933 or 1934 that Bukharin and Rykov had known about the 1932 United Opposition bloc; he suggested that maybe that was not true and that Kamenev might only have been trying to recruit support by claiming the adherence of rightist leaders. Kaganovich immediately reported these results to Stalin, who ordered proceedings against Bukharin and Rykov stopped. Two days later, Vyshinsky’s office issued a statement that there was insufficient evidence to proceed against the two rightist leaders.53

Yezhov went back to the drawing board. His arrests and interrogations of former rightists continued; over the next five months Yezhov would forward to Stalin some sixty transcripts of these interrogations. In October and November, Yezhov secured testimony about the complicity of Bukharin and Rykov from such people as Tomsky’s personal secretary and from Old Bolshevik V. I. Nevsky.54

Finally, by the first week in December, the stage was set for the arraignment of Bukharin and Rykov before the Central Committee’s plenum. Yezhov gave the main speech against them. Citing testimony from a variety of middle- and lower-level former oppositionists, he made the case that Bukharin, Rykov, and Tomsky were involved in the Zinoviev-Trotsky terrorist organization. As he would again and again, Bukharin refused to admit his party guilt and attempted to refute the charges specifically and in detail.55

Prevailing party norms meant that one was supposed to perform a discursive confession and implicate one’s confederates as a matter of party duty. Otherwise, one’s position was understood as an attack on the party and the Central Committee. Bukharin proposed a competing rhetoric, constative denial of guilt. If, as we have suggested, Bolshevik political reality was shaped by party discourse, Bukharin’s position denied not only Yezhov’s charges but his authority and, because Yezhov was a CC secretary, that of the party elite to shape that dominant narrative. For this he was denounced for “acting like a lawyer” instead of a Bolshevik and for being “antiparty.” And, in terms of party understanding, he was. Bukharin must have known this, so one wonders what he could possibly have hoped to gain by so stridently denying not only the charges but the affirming canons and group power assumptions that lay behind them.

Assuming that Bukharin was neither stupid nor suicidal, there is only one answer. At the June 1935 plenum on Yenukidze, Yezhov’s antiopposition proposal had not been authoritative. Then, in September, Stalin had saved Bukharin from the wolves by quashing the investigation against him. Now, in December, Bukharin was gambling that Stalin would again intervene to save him by contradicting Yezhov’s line. It was a risky strategy, and an unsympathetic CC audience gave him a hard time.

BUKHARIN: I am happy that this entire business has been brought to light before a war and that our [NKVD] organs have been in a position to expose all of this rot before a war so that we can come out of war victorious. Because if all of this had not been revealed before the war but during it, it would have brought about absolutely extraordinary and grievous defeats for the cause of socialism….56 But I shall begin with the following. I was present at the death of Vladimir Ilich Lenin, and I swear by the last breath of Vladimir Ilich—and everyone knows how much I loved him—that everything that has been spoken here today, that there is not a word of truth in it, that there is not a single word of truth in any of it….

MOLOTOV: That’s not the point. You are always acting as a lawyer, not just for others but also for yourself. You know how to make use of tears and sighs. But I personally do not believe these tears. These facts must all be verified, because Bukharin has so thoroughly lied through his teeth these past few years….

BUKHARIN: I have the right to defend myself.

MOLOTOV: I agree, you have the right to defend yourself, a thousand times over. But I consider it my right not to believe your words. Because you are a political hypocrite. And we shall verify this juridically.

BUKHARIN: I am not a political hypocrite, not even for a second! (Noise in the room, voices of indignation)….

SARKISOV: … So here you are swearing by Lenin. Permit me to remind you all of one story. Here Bukharin is telling you that he swears by Lenin, but, together with the Left-SRs, he in fact wanted to arrest Lenin.

BUKHARIN: Rubbish!

SARKISOV: It’s a historical fact. It’s not rubbish. You yourself said so once.

BUKHARIN: I said that the SRs suggested this, but I reported this to Lenin. How shameless of you to juggle the facts!

SARKISOV: You are not denying it. That only confirms the fact.

BUKHARIN: I told this to Lenin, and now [ironically] I am guilty of having wanted to arrest Lenin?!!!

KAGANOVICH: What are all these facts? Beginning in 1928, Kamenev established ties with Tomsky. Moreover, Bukharin was present at their conversations. We know all this from Tomsky’s statement…. And finally, in 1934 Zinoviev invited Tomsky to his dacha to drink tea. Tomsky went. Evidently, this tea party was preceded by something else, because after drinking tea Tomsky and Zinoviev went in Tomsky’s car to pick out a dog for Zinoviev. You see what friendship, what help, they went together to pick out a dog.

STALIN: What about this dog? Was it a hunting dog or a guard dog?

KAGANOVICH: It was not possible to establish this….

STALIN: Anyway, did they fetch the dog?

KAGANOVICH: They got it. They were searching for a four-legged companion not unlike themselves.

STALIN: Was it a good dog or a bad dog, anybody know? (Laughter in the hall)….

KAGANOVICH: [Their purpose was] to maintain their army, to carry out their plans pertaining to terrorist acts.

BUKHARIN: What, Comrade Kaganovich, have you gone out of your mind?!

STALIN: … We believed in you, we decorated you with the Order of Lenin, we moved you up the ladder and we were mistaken. Isn’t it true, comrade Bukharin?

BUKHARIN: It’s true, it’s true, I have said the same myself.

STALIN: [Apparently paraphrasing and mocking Bukharin] “You can go ahead and shoot me, if you like. That’s your business. But I don’t want my honor to be besmirched.” And what testimony does he give today? That’s what happens, Comrade Bukharin.

BUKHARIN: But I cannot admit, either today or tomorrow or the day after tomorrow, anything which I am not guilty of. (Noise in the room).

STALIN: I’m not saying anything personal about you.57 … It’s been very hard on you. But, when you consider all these facts which I have talked about, and of which there are so many, we have no choice but to look more closely into this matter.58

These texts from the December 1936 plenum reveal a great deal about the nature of the attack on Bukharin and his response to it. Several speakers dismissed Bukharin’s factual proofs that he could not have met with other accused at particular times. For Kosior, “Nothing is proven by that.” Molotov said, “That’s not the point. You are always acting as a lawyer.” The specific facts and charges were not the point for this party audience; Bukharin’s duty was to be politically and ritually useful.

Stalin even made jokes about Kaganovich’s laborious factual reconstruction of the story of Tomsky, Zinoviev, and the dog. And in his final interchange with Bukharin, Stalin made the point perfectly clear: Bukharin’s position now required him to provide the text that the party required, regardless of Bukharin’s “personal honor” or, indeed, of his “legal” guilt or innocence. As an exasperated Kalinin told Bukharin at the plenum, “You must simply help the investigation.” Otherwise, Bukharin would fall into the category of the party’s enemies who struck a blow at the party by committing suicide (literally or figuratively) without cooperating with the party.

The distinction between juridical guilt and party guilt holds the key to this matter and, indeed, to much that happened in the party during the period of the terror. According to party thinking, Bukharin might well be innocent in a juridical sense of the specific charges made against him, but he nevertheless was guilty on a party sense for not supporting the party’s line. That line, as was clear to all in the leading strata of the party, was the destruction of the former opposition, and as a good soldier of the party and nomenklatura, Bukharin was expected to cooperate in it.

Bukharin was obliged to do everything in his power to support that policy: to perform the denunciations of his former followers, to inform on any suspicious activities on their parts, and, if necessary, to confess and publicly associate himself with their crimes, all for the good of the party. If that meant his death, so be it. Since the Civil War, party members were in all cases supposed to be prepared to give their lives for the Revolution (which, as Bolsheviks, they believed to be synonymous with the party line). This was the price of that iron party discipline, a standard that Bukharin himself had helped to build and to which he had held others. For the Bolsheviks, personal existence was a subset of party existence, and the life of the party took precedence over physical life. As we saw from the documents above, even suicide—that most personal of acts—had only political meaning for the Bolsheviks.

Bukharin’s personal agony did not elicit sympathy or pity from his former friends on the Central Committee. (Oddly enough, Stalin’s remarks to and about Bukharin were the only conciliatory ones.) Quite the contrary, Bukharin’s refusal to follow party discipline, his putting personal honor ahead of party (and group ritual) duty, infuriated the nomenklatura. It was an attack not only on the authority of the party leadership but also on its members, and they reacted with scorn, insults, and fury at one of their own who had broken the rules and who had jeopardized party unity for personal reasons, insulting them in the process. Following the Bolshevik tradition going back to Lenin’s time, this put Bukharin outside the pale of the comrades. His speech produced a person—a reconstructed Bukharin—as an objective enemy, joining enemies that included tsarists, counterrevolutionaries, and fascists. Bukharin had spoken to the plenum as “we,” but they already thought of him as “they.” As we have seen, Bukharin’s flat denial challenged the new Yezhov line on the rightists as enemies. By refusing ritually to confess, Bukharin was also denying the nomenklatura’s right to establish the dominant narrative.

Nevertheless, the plenum did not expel Bukharin and Rykov from the party, nor did it order their arrest, despite specific proposals to that effect from some of the Central Committee members. This inconclusive result was not for want of trying on Yezhov’s part. He was direct and unambiguously accusatory in his speech, repeating the charges he had been making against Bukharin for three months. Even while the plenum was meeting, he was sending to Stalin, Molotov, and Kaganovich records of the interrogation of rightist E. F. Kulilov, who testified that Bukharin had told him in 1932 of “directives” to kill Stalin.59 The last day the plenum was meeting, Stalin apparently ordered another confrontation between the accused Kulikov and Piatakov on the one hand and Bukharin and Rykov on the other. The latter denied all the charges.

Then Stalin did a strange thing. Despite Yezhov’s condemnatory report, the lack of any support for Bukharin and Rykov from the plenum, and the damning testimony of Kulikov and others, Stalin moved “to consider the matter of Bukharin and Rykov unfinished” and suggested postponing a decision until the next plenum.60 Yezhov was again sent back to the drawing board; once again his proposals were not adopted.

We do not know the reasons for Stalin’s procrastination with Bukharin. This was the second time (the first being the time of the Zinoviev trial) that Stalin had ordered proceedings against Bukharin quashed, suspended, or delayed. It is tempting to imagine the existence of some group within the Central Committee that was resisting the move against the rightists, forcing Stalin to retreat and prepare his position again. However, there is absolutely no evidence to support this. Unlike the case of the valuable Piatakov, neither Ordzhonikidze nor any other leader interceded for Bukharin. As far as we can tell from the documents, Bukharin and Rykov were met only with unrelenting hostility and even rude insults from those present at the plenum, many of whom were prepared to order his arrest on the spot. The only person dragging his feet was Stalin. As we shall see below, this would not be the last time Stalin would resist or delay a move against Bukharin. Even in 1937, after the death of Ordzhonikidze, Stalin would show little enthusiasm for a quick and final liquidation of the leading rightists.

Perhaps he felt some special sympathy for his former friend Bukharin. Perhaps he feared some reaction from the party or country should he destroy the rightist leader. Or perhaps he merely wished to keep his lieutenants uncertain of his plans. Perhaps he himself was not sure of his plans. It was clear that Bukharin had been expected to carry out the apology ritual and had pointedly refused to do so. But unlike Yenukidze in 1935, the refusal on Bukharin’s part had resulted in leniency, not harsher punishment.

At any rate, one additional aspect of this mysterious meeting suggests hesitation or indecision on Stalin’s part. The December plenum was a completely hidden transcript. Unlike virtually every other party plenum in Soviet history, it was kept completely secret. No announcement, however terse, appeared in the party press before or after the meeting. In fact, until very recently scholars were not sure that a plenum had taken place at that time, much less that Stalin had called off the attack at the last minute. Stalin hushed it up completely. The December 1936 plenum was somehow a bungled discourse, at least for Yezhov and the other lieutenants who had called for rightist blood.

On this question too, the December 1936 plenum leaves us with more questions than answers. Was Stalin afraid to announce the meeting beforehand for fear of allowing pro-Bukharin forces to prepare? Probably not. After all, such hypothetical forces could exist only in the Central Committee, and members of that body knew of the meeting beforehand; they had even received protocols of testimony against Bukharin before the meeting. And why maintain the secrecy for years after the meeting, even to the point that someone later went back into the archives and removed the text of Stalin’s speech? Could it have been that once Bukharin’s fate was decided in 1937, there was something embarrassing about wavering or indecision back in 1936?

We can suspect, from the documents we have, some of the motivations for the new policy to destroy the opposition in 1936 and can explain some of the actions of the political players. For Stalin, the discrediting and annihilation of alternative leaders, even has-beens of the defeated opposition, had a clear political advantage, whether or not personal malice or revenge for past slights played a part. It also allowed him, by implied threat, to secure the obedience of his bureaucracy.

For the party as a whole, there were also motives for cooperation in the destruction of the opposition. Fear certainly played a part. On a very basic level, once the policy became clear no one was prepared to defend those identified as the party’s enemies for fear of joining in their punishment. No one wanted to die or lose his position and privileges. But fear alone cannot explain these events and the conduct of the political actors in them. Even though the autumn of 1936 had seen the arrest and condemnation of serving state leaders, no one in the nomenklatura could logically fear that he would become a target. They must have said to themselves: “Of course it is a serious thing to execute a Zinoviev or a Piatakov, but after all they had been dissidents and I never was anything but a loyal team player. Besides, they were clever and professional politicians and organizers, and probably were up to something unsavory.” Zinoviev and Piatakov, like other party enemies (including in their time tsarist officers, Whites, and foreign powers) belonged to the category of them, not us. Repression was something we did to them (and vice versa), and it was inconceivable that we would repress us. “I was never one of them, why should I be afraid?”

Moreover, although the political weakness of their regime meant that any threatening “new situation” was likely to inspire political fear, paralyzing personal fear did not come easily to such people. Before the revolution, many of them had spent long years in prison or Siberian exile. Yan Rudzutak had spent ten years in chains in a tsarist jail. During the Civil War, nearly all of them had been combatants; they had killed, ordered deaths, and seen comrades fall beside them. Some of them had been captured by Whites, tortured, and sentenced to death. Prison and death were not strangers to them; these were hard men and it probably took a lot to frighten them. Indeed, the accounts we have of survivors of Stalinist camps are notable for the lack of personal terror they relate during their ordeals. We need not fall back on some concept of Russian courage or fatalism to explain their mentality. Ideological fanaticism, a wartime formative experience, and Bolshevik traditions, combined with a lifetime national experience of deprivation and hard living, more than account for it.

Aside from fear, there were other reasons for the nomenklatura to support the destruction of the opposition. First, one suspects that having read the voluminous confessions of former colleagues whom they knew well, most Central Committee members believed that Bukharin was actually guilty as charged. All of these veteran Bolsheviks were intensely political persons and professional conspirators who also functioned within a longstanding cultural matrix of patrons and clients. Their lives had largely consisted of forming blocs, conspiracies, and factions. It was impossible for them to believe that Bukharin and Rykov, who were practitioners from the same school, could have cut off all contact with their adherents and clients and given up all hope of regaining influence. It simply didn’t ring true to the other members of the club who shared the same mentality. That Bukharin and Rykov did not know what their followers were doing or thinking was impossible to believe. Party circles in Moscow and Leningrad were not that large; everyone knew everyone. Conversations in kitchens and dachas, social meetings, and telephone contacts took place constantly. Who could believe that all this could have been without political content, as Bukharin and Rykov claimed? As Kosior said, “Do you want us to believe now, after all that’s happened, do you want us to believe that Bukharin … knows nothing?”

Second, the destruction of its leaders and adherents was the final neutralization of the alternative party nomenklatura. Although the threat from the opposition seems to us negligible, the elite at the time obviously felt a continuing crisis in the wake of collectivization and with the rise of German fascism: a “new situation” in which economic and social stability was still a hope and in which the final success of the Stalinist line was by no means assured. After all, they themselves had come to power unexpectedly in the midst of a national crisis twenty years before, and even Bukharin had mentioned the necessity of clearing the political decks before a war. The nomenklatura members of the Central Committee would react hysterically at the accusation that the opposition had formed a “shadow government” that awaited a crisis to seize power.

Third, those in the highest level of the elite in Stalin’s immediate circle must have felt a special urgency to destroy the former dissidents. As for Stalin and the nomenklatura in general, the “liquidation” of the opposition and its leaders was a matter of preemptive self-preservation and political insurance. But the Molotovs, Kaganovichs, and Zhdanovs of the Politburo had their own particular interests. To take the present case, as long as Bukharin was alive, they lived under an implied threat. Not so long ago Stalin had embraced Bukharin as the other of the two “Himalayas” of the party, and throughout the 1920s the two of them had virtually been corulers. Bukharin had been close to Stalin and a guest at the latter’s family gatherings.61 The fall of Bukharin and “his people” in 1929 had meant the supremacy of the Molotovs and Kaganovichs (and “their people”) in the inner circle. But Stalin’s maneuvers and sudden changes of political line in the 1920s meant that anything could happen at the top. So while Stalin’s lieutenants probably never slept very well in the dictator’s shadow, as long as Bukharin and Rykov lived, an additional threat hung over them. After their speeches to the plenum, Yezhov, Molotov, and the other senior leaders who had led the charge against Bukharin could have derived no pleasure from Stalin’s sudden turn, which abandoned their positions. Stalin’s move put the new political line in doubt. Bukharin’s denial had been a risky gamble to challenge the nomenklatura, deny Yezhov’s authority, and rely on Stalin for support. But, oddly enough, it worked.

Within the party leadership, therefore, there was an identifiable politics. It is possible to interpret the events of 1936–37 as a dynamic and constantly changing constellation of political forces. If we set aside the notion of a grand plan of Stalin’s to kill everyone (the evidence for which, aside from our knowing the end and reading backward, is quite weak), it is possible to understand the politics of the 1930s as an evolving history in which persons and groups jockeyed for position and self-interest. Stalin was desperate to achieve supreme power and to be able to discipline the apparatus. The lieutenants wanted to remain lieutenants. The nomenklatura wanted to eliminate rivals and control those beneath them. It may have been that at any given moment, all the players were maneuvering for advantage using the available political tools, issues, and discourses, without any of them, including Stalin, knowing where everything was headed. This fluid situation was described fifty years later by Molotov, who admitted his role in the terror and still believed it to have been necessary. For Molotov, the developing events were “not simply tactics. Gradually things came to light in a sharp struggle in various areas.”62