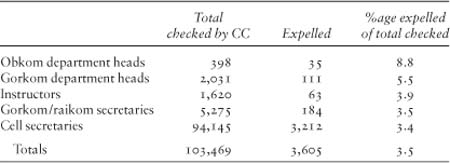

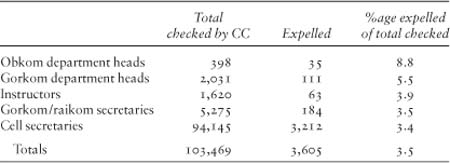

Table 5

Verification and Expulsion of Party Cadres, 1935–37

Source: Malenkov speech to February–March plenum, Voprosy istorii, no. 10, 1995, 7–8.

If you knew someone, you’d give him your full trust. Everything was based on these connections and on trust. How can one do such things?!

—A. A. Andreev, 1937

I consider the criticism and the Party sanctions levied against me personally by the Central Committee to be, in my opinion, very lenient,—because of the enormous harm caused by me as a result of the activities of these Trotskyists.

—B. P. Sheboldaev, 1937

IN JANUARY 1937 Moscow decided to press the point about the dangers of “carelessness” among the regional nomenklatura by making examples of two of the most prominent regional leaders, Pavel Postyshev (first secretary in Ukraine) and Boris Sheboldaev (first secretary of the Azov–Black Sea Territorial Party Committee). Recent arrests of alleged Trotskyist terrorists in both regions provided a setting for criticizing the practices of the regional satraps without delving too much into the real workings of the system and without weakening the regional party apparatus as an institution, both points which nobody wanted to discuss. The new Moscow political transcript went as follows: the arrests of terrorists under the noses of trusted, veteran party leaders reveal deficiencies in leadership. The leading secretaries had been too trusting, too “politically blind,” and too involved in economic administration to pay the necessary attention to “party work.” Their laxity had allowed the enemy to work unmolested, and the bureaucratism and “familyness” of their machines made them deaf to “signals from below” about enemies.

It is clear that this new line was carefully thought-out and presented by the Stalinist center. By criticizing the regional leaders and making examples of two of the most prominent, Stalin could have been serving several purposes. These actions first of all allowed Stalin to root out former oppositionists down to the local level. Local party leaders were no longer able to shield such people, regardless of their talents and usefulness to local economic and administrative agencies. The new policy thus weakened local patronage control and made it clear that Moscow would have a say in hirings and firings and would intrude itself into cadres policy. The new line also showed territorial party leaders who was boss and put them on notice that they must toe the current Moscow political line. By encouraging rank-and-file criticism, within limits, Stalin also attempted to open up new lines of information (or denunciation) that bypassed the middle-level leadership, which before this had been able to squelch discontent and filter information coming from below.

At the same time, the tsar could not govern without his nobles, or at least without a boyar class. The new critical line against the party apparatus was carefully circumscribed. While the leaders were criticized, they were not denounced as enemies, conscious protectors of enemies, corrupt, or even poor Bolsheviks. Stalin made this very clear in his speech to the February–March plenum, which was prominently published in party newspapers.1 The two leading secretaries who lost their jobs were given new posts as heads of other provinces. Grassroots criticism was to be kept under control and channeled against particular leaders and their faults rather than against the regime itself.

These Stalinist tactics were risky for the nomenklatura, whose smooth functioning at all levels was based on patronage control, on maintaining control over the rank-and-file members (as well as the population at large), and on a unified narrative at all levels of the nomenklatura. Stalin’s criticism from below–party democracy tactic risked a split in the party elite by turning the top against the middle and by inciting the rank and file against their heretofore legitimate leaders. Although at this time the regional leaders were not branded as enemies or their loyalty questioned, the new political transcript from the top represented the beginning of Stalin’s offensive against the nomenklatura. Ironically, it had been this very idea—organizing the lower levels of the party against their leaders— that had so terrorized and infuriated the nomenklatura as a whole when Riutin had suggested it.

In the first week of January, the Stalinist emissary A. A. Andreev traveled to Rostov-on-Don to organize the removal of Boris Sheboldaev, the powerful first secretary of the Azov–Black Sea Territorial Party Organization, and thereby to promulgate the new line on careless regional secretaries. In the autumn of 1936 the spreading arrests of former Trotskyists had reached into Sheboldaev’s province, and he had been summoned to the Politburo for a dressing down about the tolerance he had shown for them. On 2 January the Politburo passed a resolution removing him from his position, and it was this text that Andreev carried with him to Rostov-on-Don, the capital of the territory, to validate the new line. Convening first the narrow leadership circle and then the broader provincial elite, Andreev laid out the Politburo’s decision, chastised the Sheboldaev team, and encouraged lower-level party members to help root out incompetent leaders and traitors. As usual, the procedure by which a party leader was disciplined was a kind of performance ritual with its own internal set of rules. An emissary from the “center” arrived and arraigned the local leader. Thus in Rostov, emissary Andreev told the regional party leaders that “The Trotskyist center carried out its activities in Rostov with impunity for a fairly long period of time…. The reason [for the enemy’s success] is the extremely uncritical, credulous attitude—inadmissible for a Bolshevik—on the part of people such as Comrade Sheboldaev, a member of the CC.”2 That leader then provided the required apologetic “tax payment” by confessing his error and pointedly affirming the justice of the charges (usually by saying that they were “completely correct”). Then those in attendance affirmed the accusations by providing additional details and charges. Finally, a resolution was adopted that transformed the new discourse into a formal text.3

Unlike Yenukidze and Bukharin, Sheboldaev understood the need for an apologetic performance and recognized that he did not have the stature or influence to avoid it. Such a speech was necessary both to affirm the unity and “correctness” of the party leadership and to reinforce Sheboldaev’s implicit claim to continued membership in the elite. Playing the role expected of him as a loyal member of the nomenklatura, Sheboldaev bowed before the Central Committee’s will and took his medicine by performing a ritualized affirmation of the new dominant line: “Comrades, I have come up to the podium for only one reason, namely, to say that I consider the decision by the Central Committee of the VKP(b) concerning my mistakes and the work of the Territorial Committee of the VKP(b), of which I was the leader, to be absolutely right, absolutely just, because no other decision by the CC of the VKP(b) is possible…. Comrades, I consider it to be absolutely correct that the chief and main responsibility for this state of affairs should be placed on my shoulders.”4

For loyally participating in the required apology ritual, Sheboldaev escaped severe punishment. Although he was removed from Rostov, he immediately received another important posting in another party organization. Encouraged by the new line and freed from Sheboldaev’s control, party members then unleashed heretofore impossible criticism of the former provincial party leadership. No less than Sheboldaev himself, they were playing roles of contributing to party unity and affirming their status.

G. M. Malenkov, head of the personnel registration sector of the Central Committee, had accompanied Andreev to Rostov. Whereas Andreev had emphasized the theme of vigilance against enemies, Malenkov concentrated on the lack of democracy and input from below that had characterized Sheboldaev’s leadership.5

In the discussion, there was criticism of several members of Sheboldaev’s former leadership team. One special target was the territorial chief of the Party Control Commission (KPK), the party’s disciplinary body that was supposed to have been more vigilant against the recently uncovered Trotskyists. Comrade Brike of the KPK was frequently denounced from the floor. Here we have an example of Moscow wanting to keep the criticism within manageable limits by carefully trying to shape the language. Brike, as KPK representative, answered to the party’s KPK in Moscow, which was headed in early 1937 by N. I. Yezhov. As someone with such a powerful potential protector, Brike was rescued by Malenkov: “Comrades, the draft resolution includes an assessment of the activities of the Plenipotentiary of the KPK. The Central Committee shall concern itself with this matter, and this matter shall henceforth become the Central Committee’s concern.” The transcript next has a chorus of voices asking, “But may we ask about it?” followed by laughter.6

In the wake of Andreev’s visit, district party meetings around the province removed members of the Sheboldaev team. In accordance with party tradition, larger meetings of party activists were organized to promulgate and discuss Moscow’s decision to remove Sheboldaev.7 These meetings dutifully adopted resolutions in favor of the change and sent corresponding affirmations to the center.

These discursive rituals were the vehicles by which policies were implemented. Everyone played his part. But it is again important to remember that these were not hollow or a priori invented events. They responded to and at the same time influenced real political events in the localities. In the present case, for example, the new rhetoric prompted calls in these party organizations to speed up the reexamination of cases of rank-and-file members who had been expelled in the previous year’s verification and exchange of party documents. Sheboldaev’s subordinates had carried out these expulsions; the implication was that if they had so misread the danger of Trotskyism, they might well have expelled the wrong people. Stalin had said as much at the June 1936 plenum.

Shortly after Sheboldaev’s removal, Pavel Postyshev, who was second secretary of the Ukrainian party organization and first secretary of the Kiev Party Committee, was also reprimanded and deprived of one of his posts. Seven weeks later, he was fired from his position as Ukrainian party secretary and transferred to the position of first secretary of the Kuibyshev Provincial Party Organization.8

The demotions of Sheboldaev and Postyshev were significant events. These were powerful men who had acted practically as independent princes of their territories. Their censures were accompanied by a visible political campaign against “suppression of criticism” and “violations of party democracy.” At the February–March 1937 plenum of the Central Committee, A. A. Zhdanov would give a fiery speech on these themes, decrying the practice of “co-option” by which regional party leaders had refused to call party elections, instead appointing their favorites to high positions in their machines. Zhdanov called for mandatory party elections to be held in May of 1937 in which party leaders at all levels were to face reelection in unprecedented secret-ballot voting by the party rank and file. Several Central Committee members greeted Zhdanov’s electoral proposal with lukewarm enthusiasm; some even openly suggested postponing the voting for various reasons.9 But Stalin defended Zhdanov’s proposal for new party elections.10

The new emphasis on “party democracy” authorized lower-level party members to criticize their superiors for poor work and suppression of criticism. Before the plenum, such criticism was dangerous; it almost always led to retaliation by the regional machines that controlled the fates of party members in their provinces. But the February–March plenum unleashed serious insurrections within the party by authorizing and protecting critics. In one district of the Western Region, for example, a membership meeting expelled the local district party secretary against the wishes of the regional committee. Representing the regional party machine, the local NKVD chief tried to defend the district secretary, to no avail. Protecting one of their own, the regional leadership gave the ejected leader a job in the regional party committee.11

The criticism of regional party chiefs in early 1937 also revisited the issue of who had been (and should not have been) expelled in the recently completed membership screenings of 1935–36, the verification and exchange of party documents. As we have seen, those operations had been under the control of the regional chiefs themselves and had resulted in mass expulsions of rank-and-file party members; only rarely were any full-time party officials expelled in these screenings. We saw that in June 1936 Stalin and others had complained about this practice and had ordered the territorial leaders to “correct mistakes” by speeding up appeals and readmissions of those who had been expelled for no good reason. In early March 1937 top-level Moscow leaders again denounced the “heartless and bureaucratic” repression of “little people.” Malenkov noted that more than one hundred thousand of those expelled had been kicked out for little or no reason, while Trotskyists who occupied party leadership posts had passed through the screenings with little difficulty.12

Stalin echoed the theme in one of his speeches to the February–March 1937 plenum. According to him, by the most extravagant count the numbers of Trotskyists, Zinovievists, and rightists could be no more than thirty thousand persons. Yet in the membership screenings, more than three hundred thousand had been expelled; some factories now contained more ex-members than members. Stalin worried that this was creating large numbers of embittered former party members, and he blamed the territorial chiefs for the problem: “All these outrages that you have committed are water for the enemy’s mill.”13 In the case of Postyshev’s removal, Stalin and others had taken up the cause of one Nikolaenko, a party member expelled by Postyshev’s wife Postolovskaia in Kiev. “Signals” from “little people” like Nikolaenko about enemies had been ignored by Postyshev, who had instead persecuted those sending the warnings.14

Certainly, much of this rhetoric was demagogic posturing. For Stalin and other central leaders it was good political policy to pose as the defenders of the rank and file against the depredations of evil boyars. Indeed, although appeals and reconsiderations continued throughout the 1930s, many of these little people were never readmitted. Moreover, it was time-honored practice for higher leaders to blame their subordinates for unpopular or mistaken policies and for the subordinates dutifully to admit their mistakes.

On the other hand, even in the darkest days of the hysterical hunt for enemies in 1937 and 1938, most of those expelled back in 1935 and 1936 who appealed to Moscow were reinstated. Virtually all those expelled for “passivity” were readmitted, and appellants charged with more serious party offenses who appealed to the Party Control Commission in Moscow (run by Yezhov and later by the equally fierce Shkiriatov) were usually readmitted, the proportion of successful appeals reaching 63 percent by 1938.15

Furthermore, a good bit of Stalin’s criticism was hidden behind closed doors to the Central Committee and never intended for public consumption, thus reducing any demagogic impact. More important, statistical data presented by Malenkov and never released to the public showed vast differences between regional officials’ and Moscow leaders’ versions of membership verification. Table 5 shows that the screenings had targeted masses of rank-and-file party members in 1935 and 1936 when checking was done by territorial officials. However, after the screenings, verification of party members was under the direct control of the Central Committee, and the results were different. When “checking” was done by central, rather than territorial, authorities, the attrition was heavier at the top than at the bottom. Moscow was less interested in (and even hostile to) mass expulsions of the rank and file; its targets were former Trotskyists with rank. Clearly, Moscow and the regional secretaries had different ideas about what the screenings should have accomplished.

At the February–March 1937 plenum, Stalin criticized the undemocratic practices of party officials in the provinces but drew a sharp line between their “mistakes” and the “enemies” who needed to be “smashed.” “Is it that our party comrades have become worse than they were before, have become less conscientious and disciplined? No, of course not. Is it that they have begun to degenerate? Again, no. Such a supposition is completely unfounded. Then what is the matter? … The fact is that our party comrades, carried away by economic campaigns and by enormous successes on the front of economic construction, simply forgot some very important facts.”16

Table 5

Verification and Expulsion of Party Cadres, 1935–37

Source: Malenkov speech to February–March plenum, Voprosy istorii, no. 10, 1995, 7–8.

The Politburo was at pains to show that Sheboldaev and Postyshev were not to be considered enemies themselves; they had simply been negligent, even though Sheboldaev’s personal secretary and most of Postyshev’s lieutenants in Kiev had been arrested as Trotskyists. While criticizing Sheboldaev, Postyshev, and others, several speakers at the plenum cited mitigating circumstances: such leaders were, in fact, burdened with economic work and were not completely at fault. Significantly, both secretaries were transferred to lesser but significant posts: Postyshev became first secretary of Kuibyshev Region, and Sheboldaev was sent to head the Kursk party organization. A. A. Andreev, who had led the sacking of Sheboldaev, had prepared a resolution for the February–March plenum linking Sheboldaev and Postyshev and denouncing them in rather strong language.17Apparently, though, it was Stalin’s decision not to promulgate such a strong statement, and the resolution was never introduced.

Similarly, in the weeks that followed the transfers of these two, the Central Committee intervened on several occasions to protect them from those who sought to characterize their demotions more negatively. In one case, a newspaper editor in the Azov–Black Sea Territory was reprimanded after allowing publication of an article saying that Sheboldaev had been fired. In another instance, Stalin intervened personally as late as July 1937 to order a “campaign against Comrade Postyshev” stopped. As always, precise conventions of language had to be followed precisely.18

Although there was a critical but generally conciliatory attitude toward the regional secretaries at the February–March plenum, the official rhetoric on former oppositionists was increasingly severe. Two months earlier, at Stalin’s suggestion, the previous plenum had not condemned Bukharin and Rykov and had postponed consideration to the next meeting. In the interim, Yezhov had been busy. He continued to interrogate former oppositionists in order to get “evidence” incriminating the rightist leaders. On 13 January 1937 Bukharin participated in a “confrontation” with V. N. Astrov, a former pupil of Bukharin now arrested for treason. In the presence of Stalin and other Politburo members, Astrov angrily accused Bukharin of active participation in subversive conspiracies. Allegedly, Bukharin had used his former students in the Institute of Red Professors (the “Bukharin School”) as the basis for an underground organization. Bukharin denied everything.19

Between 23 and 30 January, Moscow was the site of the second of the famous show trials. This time, Deputy Commissar of Heavy Industry Piatakov, the journalist Karl Radek, the former diplomat G. Sokolnikov, and fourteen other defendants were charged with industrial wrecking and espionage at the behest of Trotsky and the German government. As before, all the defendants confessed to the charges.

The stage was now set for Bukharin’s next arraignment at the upcoming plenum of the Central Committee, scheduled for 19 February 1937. The meeting had to be postponed, however, because of the sudden death of Heavy Industry Commissar Sergo Ordzhonikidze on the eighteenth. Officially announced as heart failure, his death now seems clearly to have been a suicide. Subsequent testimony from those around him suggests that he had been despondent for some time, and there is information that he had had arguments with Stalin, perhaps about those from his agency who had been arrested.20

The plenum was rescheduled to open 23 February, but the drama began three days earlier, when Bukharin sent two documents to the Central Committee. The first was a letter again protesting his innocence and announcing that he was beginning a hunger strike on the twenty-first to protest the accusations against him. He wrote on the twentieth, “I cannot live like this any more. I have written an answer to the slanderers. I am in no physical or moral condition to come to the plenum, my legs will not go, I cannot endure the existing atmosphere, I am in no condition to speak…. In this extraordinary situation, from tomorrow I will begin a total hunger strike until the accusations of betrayal, wrecking, and terrorism are dropped.”21

Along with this letter, which he asked the Politburo not to circulate to the full Central Committee, Bukharin forwarded a statement to that body of more than one hundred pages in which he attempted to refute, point by point, the charges made against him.22 With careful detail, he showed the inconsistencies among the various confessions and statements implicating him and in many cases proved that he could not have been in the places indicated by his accusers. He maintained his complete loyalty to Stalin’s party line since 1930, again denied charges of terrorism and treason, and expressed outrage that such accusations could even have been made. Moreover, in a subtle way, he questioned the honesty of the secret police by alluding to the fact that confessions could be supplied by defendants according to the demands of the police.

It would seem that Bukharin’s only chance to survive, and it was a slim one, was to agree with the charges, to “come clean,” confess to everything, and throw himself on the mercy of the Central Committee. Only in this way could he “disarm” completely before the party, “clean himself of the filth he had fallen into,” as Stalin was to say, and provide the service— as a public counterexample—that the party demanded. After all, that was the standard Bukharin had demanded of the Trotskyists back in the 1920s, and for him to deny it now with a legalistic defense was bound to make him look self-serving and hypocritical to his comrades.

His hunger strike and initial refusal to attend the plenum (both of which he retracted almost immediately) were taken as vivid examples of an antiparty stance, or, as Mikoian would call it, a “demonstration” against the party no less insulting or threatening than an actual street rally against the Bolsheviks. In this light, how could Bukharin have hoped to prevail or even survive by continuing to deny the charges? Perhaps he based his position on the ambiguous outcome of the previous plenum, when he had challenged Yezhov’s sally and Stalin had blocked Bukharin’s demise. If he counted on a reprise in February, however, he was wrong.

The plenum opened on 23 February with the formal report by Yezhov on the charges against Bukharin and Rykov. In the days before the plenum, members of the Central Committee had received voluminous materials on these charges, including lengthy transcripts of the confessions of Bukharin’s former associates. Yezhov’s speech, therefore, contained few specifics but rather summarized the accusations. Beginning with a long survey of the history of the Right Opposition, he said that the former rightists, like the Trotskyists, had formed underground terrorist cells with the goal of carrying out espionage and assassinations against the Soviet government. This conspiracy had as its founding document the Riutin Platform, the dangerous competing discourse of 1932, which Yezhov now said that Bukharin had at least commissioned, if not written.

Yezhov went on to say that on the basis of “incontrovertible documentary materials” there was no question that Bukharin and Rykov had at least known of preparations for the Kirov assassination and had conspired to kill other party leaders as part of a planned “palace revolution” to overthrow the party. “It seems to me that all this raises, in connection with Bukharin and Rykov, people who are fully responsible for the whole activity of the right opposition in general and for their anti-soviet activity in particular,—raises the question of their continuation not only in the Central Committee but also as members of the party.” Voices from the plenum responded, “Right,” and “It is too little.”23

Yezhov was followed by A. I. Mikoian, who was no less severe in his castigation of Bukharin and Rykov as traitors and assassins. Mikoian noted that Trotsky’s tactics since the late 1920s had been to organize various declarations, protests, and demonstrations against the party leadership: “Bukharin, following in enemy of the people Trotsky’s footsteps, turned his arms against the Central Committee. It was Trotsky who was always putting forth ultimatums, Trotsky always hurled written statements at us…. Trotsky even organized demonstrations against the party on the street, but Bukharin does not have the possibility to organize a demonstration, now he has no masses, it is another time…. When there are no masses, no other means of protest, then Bukharin resorts to a hunger strike as a form of protest.”24

Even if for the sake of argument one accepted Bukharin’s claim that he did not order any assassinations, Mikoian continued, it was clear from the testimonies of his former associates that Bukharin must have at least known the things they were planning. In Mikoian’s words, “One thing nobody can argue with. To know of terror against the leadership of the party, of wrecking in our factories, of espionage, of Gestapo agents, and to say nothing about it to the party—what is this?! … The rightist terroristic activities were known to Bukharin, he knew that they were preparing terrorist acts against the leadership of the party, he knew and he did not tell the Central Committee. Is this permissible for a member of the Central Committee and a member of the party?! It is proved and clear even to a blind man.”25 Finally, it was Bukharin’s turn to speak. He was not to have an easy time of it.

BUKHARIN: If you think that [my accusers] told the truth, that I issued terroristic instructions while out hunting, then I won’t be able to change your mind. I consider this a monstrous lie, which I can’t take seriously.

STALIN: You babbled on and on, and then you forgot.

BUKHARIN: I didn’t say a word. Really!

STALIN: You really babble a lot.

BUKHARIN: I agree, I babble a lot, but I do not agree that I babbled about terrorism. That’s absolute nonsense. Just think, comrades, how could you ascribe to me a plan for a palace coup?!26

Bukharin was followed to the podium by his fellow rightist leader Aleksei Rykov, who was also grilled by the CC.27 After Bukharin and Rykov spoke, the plenum saw one Central Committee member after another go to the podium and denounce the two in the strongest possible terms. This arraignment lasted more than two days.

SHKIRIATOV: Enough, we must put an end to this, we must make a decision. Not only is there no place for these people in the CC and in the Party. Their place is at a court of law, their place, i.e. the place of these state criminals is in the dock.

[KOSIOR: Let them prove it at a court of law.]

SHKIRIATOV: Yes, at a court of law. What makes you think, Bukharin and Rykov, that leniency will be shown to you? Why? When such feverish work is carried out against our Party, when these people are organizing conspiratorial, terroristic cells against the Party in order, by their terroristic actions, “to put the members of the Politburo out of their way.” We cannot limit ourselves to merely expelling them [Bukharin and Rykov] from the Party. This must not be! The law established by the socialist state must be applied to the enemy. They must not only be expelled from the CC and from the Party. They must be prosecuted….

VOROSHILOV: Bukharin is a very peculiar person. He is capable of many things. Vile, you know, as a mischievous cat and at once he starts covering his tracks, he starts confusing things, he starts carrying out all kinds of pranks, in order to come out of this filthy business clean, and he had succeeded in this often thanks to the kindness of the Central Committee…. He must not get away with it. The Central Committee is not a tribunal. We do not represent a court of law. The Central Committee is a political organ….

I believe that the guilt of this group, of Bukharin, of Rykov and especially of Tomsky, has been completely proven.28

A. A. Andreev noted Stalin’s “patience” in the matter of prosecuting Bukharin and the others:

No, no, as far as you are concerned, the Party and the Central Committee have given you sufficient time, more than enough time and means to disarm yourselves and prove yourself innocent. No one else from the ranks of the oppositionists and enemies has been afforded such a period of time, the Party has not afforded such a period of time to anyone other than you. The Party did the maximum to keep you in its ranks. How much effort has been expended, how much patience has been shown to you by the Party, and especially, I must say, by Comrade Stalin. Yes, precisely, by Comrade Stalin, who always urged us, who constantly warned us, whenever comrades here or there, whenever local organizations here or there raised the issue “pointblank,” as is said, in reference to the rightists and whenever the question would arise in the CC, Comrade Stalin would caution them against excessive haste, he always warned us. Nevertheless, you abused the Party’s trust.29

At this point, Komsomol leader Kosarev tried to summarize and end the discussion.

KOSAREV: It seems to me that the time has come for us to stop calling Rykov, Bukharin and other rightists comrades. People who have laid their hands on our Party, on the leadership of our Party, people who have lifted their hands against Comrade Stalin, cannot be our comrades. They are enemies, and we must deal with them as we would with any enemy. Bukharin and Rykov must be expelled from the register of the Central Committee and from the Party. They must be arrested at once and brought to trial for working as enemies against our socialist country.

Exclamations from many sides: Right! Right!30

Molotov noted that the real point was Bukharin’s and Rykov’s duty to set an example to others by “disarming.” By refuting the charges, they were giving aid and comfort to the enemy and sending dangerous signals to others:

But we must consider the fact that there are enemies in our midst. When they give a signal such as: “Hold on, keep on struggling, don’t give up, deny the truth, deny the evidence, dodge, duck,”—this still leaves some people in the position of enemies, of people who have not disarmed themselves. It’s not Rykov and Bukharin,—they have other people, they have been in our Party and they are still in it now. We cannot close our eyes to this. They call out not only to their supporters in our Party, but also to those who are outside the Party. They give them their signal. It is clear from the policies of Bukharin and Rykov at the present time that they have strayed much further along the path of doubts and errors, that they have strayed far, that they are straying more and more, that they are continuing their worse traditions of struggling against the Party….

Already at the last Plenum we had sufficient evidence, and yet we postponed this case once again. We decided to give this man the opportunity to extricate himself if he is in trouble. If he is guilty, we’ll give him time to admit his mistakes, to turn aside from it, to repent of it, to put an end to it. We have sought to bring this about in every way possible.31

Mikhail Kalinin made a point that everyone in the room understood; that there was a difference between judicial guilt and political guilt. It was the latter that mattered:

And when some people shouted at Bukharin during his speech that, namely, you are acting like a lawyer, Bukharin replied: “Well, what of it? My situation is such that I must defend myself.” I think, and those comrades who shouted at him also probably think, when they speak of “acting like a lawyer,” that it doesn’t mean that Bukharin should not defend himself. That’s not the point. What it means, instead, is that, in defending himself, he is employing the methods of a lawyer who wants, at whatever cost, to defend the accused, even when the latter’s case is completely hopeless…. It means that he assumed a priori that there were two camps here, namely the CC and Bukharin.32

For Kalinin and the other CC members, the matter was clear: There were young hotheads prepared to use violence to change the system. There was talk about palace coups in groups that practiced conspiratorial secrecy behind a facade of loyalty. Yes, Bukharin and Rykov had confessed their previous political mistakes and publicly associated themselves with the party majority. But they had done it without enthusiasm, without commitment. They knew, or at least must have heard about, the incendiary sentiments of their former followers; how could they not? They saw each other in meetings, on the street, in kitchens, at dachas. Bukharin’s legalistic and logical-factual attempts (“like a lawyer”) to prove that he could not have been a member of any conspiracy were entirely beside the point and insulting to his comrades on the CC. To lifelong professional politicians and conspirators, it was simply inconceivable that Bukharin had not known about his followers’ subversive and potentially violent subculture. Not to report that was tantamount to participating in it. Those were the rules, rules that Bukharin had helped craft and apply to others, and everybody understood them.

After this litany of denunciations from Central Committee members, Bukharin was given another chance to speak. Allowing those accused of party crimes to speak a second time in rebuttal was a fairly unusual procedure, and was cited by some speakers as proof that the Central Committee was willing to give him every fair chance to defend himself. As before, however, he was not allowed to speak unmolested.

BUKHARIN: Comrades, first and foremost, I must tell you that I shall disregard all sorts of attacks bearing, to a significant extent, on my personal character, attacks which depicted me either as a buffoon or as a subtle hypocrite. I cannot dwell on the unworthy aspect of these speeches and I consider this entirely superfluous…. But that is not at all my main argument. I have compared facts, many chronological dates. Armed with this comparison, I’ve refuted everything.

MOLOTOV: Nothing of the sort. Your refutation is not worth a farthing, because we have enough facts.

BUKHARIN: I would be grateful if someone, anyone were to mention it, but not a single person has mentioned it, no one has said a word about it.

MOLOTOV: My God! Everybody is talking about it….

BUKHARIN: In spite of the fact that I cannot explain a host of things, fair questions posed to me, [in spite of the fact that] I cannot explain fully or even half-fully many questions posed to me concerning the conduct of people testifying against me. However, this circumstance, namely, that I cannot explain everything is not in my eyes an argument for my guilt. I repeat, I’ve been guilty of many things, but I protest with all the strength of my soul against being charged with such things as treason to my homeland, sabotage, terrorism and so on, because any person possessing such qualities would be my deadly enemy. I am ready and willing to do anything against such a person. (Noise, voices.) …

KHLOPLIANKIN: It’s time to throw you in prison!

BUKHARIN: What?

KHLOPLIANKIN: You should have been thrown in prison a long time ago!

BUKHARIN: Well, go on, throw me in prison. So you think the fact that you are yelling: “Throw him in prison!” will make me talk differently? No, it won’t.33

In accordance with party traditions, the reporter on the agenda question was given a chance to give a concluding speech. In this case, Yezhov summed up the case against Bukharin and Rykov. Although his original report had called only for expelling them from the party, his concluding remarks suggested that they should be arrested.34

From the speeches to the plenum, it seemed that there was little disagreement on the question. None of the speakers even came close to defending Bukharin or opposing arrests of the traitors. They were furious with Bukharin and Rykov not only for their alleged “treason” to the party but for their refusal to serve the party and the ritual by playing the prescribed roles. Regardless of Bukharin’s intent, his speech in ritual context transformed him into an enemy. Once again, the senior nomenklatura had closed ranks against those perceived as violating their rules. However, even though we have a version of the entire text concerning Bukharin and Rykov, the plenum’s proceedings to a great extent remain mysterious. Indeed, the documents themselves raise strange questions.

Since Lenin’s time, it had always been a party tradition that the main reporter on an agenda question offered a draft resolution beforehand. More recently, it had become the responsibility of the Politburo (that is, of Stalin himself) to prepare such a preliminary resolution in advance of the plenum. These drafts were circulated to the Central Committee members before the report, and speeches were given. In the present case, there was a draft resolution to be adopted on the basis of Yezhov’s main report. The draft has not been located in the archives; presumably it followed the outlines of Yezhov’s recommendation and called for expelling Bukharin and Rykov from the party.

In the vast majority of cases in the 1930s, discussion of the main report was perfunctory, and although minor corrections and amendments might be offered and even accepted from the floor, the Central Committee almost always voted unanimously to adopt the draft resolution. In rare cases when there was disagreement or when the drift of the meeting went beyond the draft proposals, an ad hoc commission of Central Committee members would retire during the meeting to work out a new text for the final resolution. (This had happened at the 17th Party Congress in 1934, when Ordzhonikidze and Molotov had proposed different industrial targets for the second Five Year Plan.)35

In this case, several of the speakers had gone beyond Yezhov’s formal recommendation for expulsion. No doubt sensing the winds, some of them —including Yezhov—had called for arresting Bukharin and Rykov. Others had flatly suggested that they be shot. Formally, then, it was necessary for a commission to edit the draft resolution in favor of stronger measures. But the matter was more complicated than that. There is evidence that some, perhaps including Stalin himself, may have argued for a different approach altogether. The resolution subsequently produced by the commission and approved by the plenum did, in fact, consign Bukharin and Rykov to the not-so-tender mercies of the NKVD. However, it contained language indicating indecision at the top.36 The ambiguity arises from Stalin’s report to the plenum on the deliberations of the ad hoc commission. Stalin told the plenum,

There were differences of opinion as to whether they should be handed over for trial or not handed over for trial, and if not, then as to what we should confine ourselves to. Part of the commission expressed itself in favor of handing them over to a Military Tribunal and having them executed. Another part of the commission expressed itself in favor of handing them over for trial and having them receive a sentence of 10 years in prison. A third part expressed itself in favor of having them handed over for trial without a preliminary decision as to what should be their sentence. And, finally, a fourth part of the commission expressed itself in favor of not handing them over for trial but instead referring the matter of Bukharin and Rykov to the NKVD. The last-named proposal won out….

There were some on the commission, a rather substantial number, as well as here at the CC Plenum, who felt that there was apparently no difference between Bukharin and Rykov, on the one hand, and those Trotskyists and Zinovievists, on the other hand, who were brought to trial and punished accordingly. The commission does not agree with such a position and believes that one ought not to lump Bukharin and Rykov in with the group of Trotskyists and Zinovievists, since there is a difference between them, a difference that speaks in favor of Bukharin and Rykov.

If we look at the Trotskyists and Zinovievists, we see that they were expelled from the Party, then restored, then expelled again. If we look at Bukharin and Rykov, we see that they had never been expelled. We should not equate the Trotskyists and Zinovievists, who had once, as you well know, staged an antiSoviet demonstration in 1927, with Rykov and Bukharin. There are no such sins in their past. The commission could not fail but take into account that there are no such sins in the past actions of Bukharin and Rykov and that, until very recently, they gave no cause or grounds for expelling them from the Party.37

It was quite unusual for Stalin himself to give such reports; this is the first and only time in party history that he did so. This text was truly a hidden transcript: it was never published with any of the versions of the stenographic report and was never transferred to the party archives with other materials of the plenum. The transcript of this ambiguous and contradictory decision on Bukharin never even found its way into the heavily edited and limited-circulation stenographic report, which showed the plenum beginning on 27 February—four days after it actually started.38

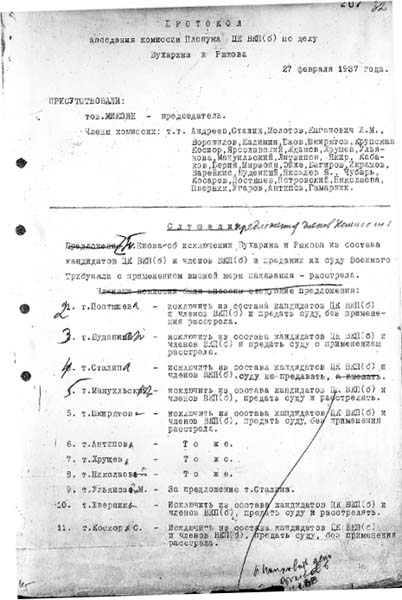

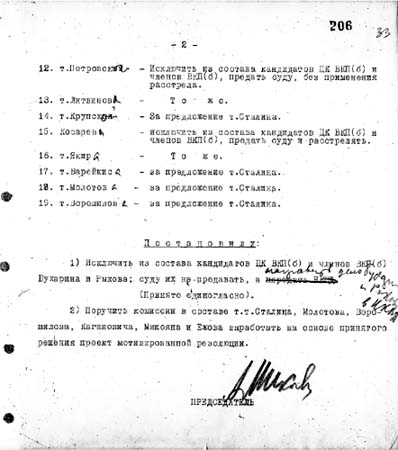

We have two versions of the skeletal protocol of the commission’s deliberations on which Stalin reported. Apparently one of them was made during the meeting; the other seems to have been edited immediately thereafter. The alterations made to this document raise more questions than they answer.

First, in the original protocol, Yezhov was the main reporter who proposed handing Bukharin and Rykov over to the courts and executing them. However, because this was not the final result and because party discursive tradition prohibited even a private admission that a formal report was rejected, the document was doctored to make it appear that there had been no proposal from Yezhov, but rather a round table with numbered “exchange of opinions” among the members of the commission.

But although expulsion from the party was a foregone conclusion, in the original polling not a single member proposed or voted for what would become the final decision: turning the matter of Bukharin and Rykov over to the NKVD for further investigation. In the initial polling of thirty-six members of the commission, six (Yezhov, Budennyi, Manuilsky, Shvernik, Kosarev, and Yakir) spoke for executing Bukharin and Rykov. Eight (Postyshev, Shkiriatov, Antipov, Khrushchev, Nikolaeva, Kosior, Petrovsky, and Litvinov) were for arresting and trying Bukharin and Rykov but for sentencing them to prison rather than to death. Sixteen members expressed no opinion, or perhaps their votes were not recorded.

It is the remaining group of six voters that is especially intriguing. In the original protocol, five members were “for the suggestion of Comrade Stalin.” But what was that suggestion? In the original document, Stalin spoke against the death penalty, a prison sentence, or even a trial, and in favor of the relatively lenient punishment of internal exile. But in the final version, Stalin’s “suggestion” had become the final decision not to send them to trial but to turn the matter of Bukharin and Rykov over to the NKVD for further investigation. These documents make it clear that there really was indecision and a discussion that changed Stalin’s mind. The result was a compromise of all the suggestions.

Once again Stalin was resisting application of either a prison or death sentence. Why? It may have been that he was lying back, proposing a light punishment in order to see what the others said, thereby identifying those with “soft” views on the opposition and marking them for later retaliation. In this way, he would be able to test the level of support for his plan to kill off the former opposition. This could explain why some, aware of the game, simply expressed themselves in favor of Stalin’s proposal while others kept silent. Mitigating against this explanation, however, is the lack of any correlation between the penalties proposed by those present and their fates. Thus Shkiriatov, Khrushchev, Nikolaeva, Petrovsky, and Litvinov voted against the sternest punishment, execution, but all survived the purges. Kosarev, Yakir, and Yezhov voted for execution and were themselves arrested and shot.

It is far more likely that Stalin had not decided exactly how far to proceed against Bukharin and Rykov. As the final resolution showed, it had not been “proved” that they had in fact joined the Trotskyist “terror organization.” Rather, “at a minimum” they knew about the Trotskyists’ plans, which is not the same thing. Yezhov had been the one closest to the investigations and interrogations of the rightists. Back in the fall of 1936, he had written to Stalin to express “doubt[s] that the rightists had concluded a direct organizational bloc with the Trotskyists and Zinovievists.” At that time, Yezhov recommended a “minimum punishment” of exile to a far region for Bukharin and Rykov.39 Yezhov’s 1936 formulation was precisely the one voiced by Stalin at the February–March 1937 plenum: that “at a minimum” Bukharin and Rykov had known about the terrorist plans of others and failed to report them. A distinction was made between them and the Trotskyists, and Stalin’s first proposed punishment was exile. He used the same word (vysylka) that Yezhov had used in his letter the previous autumn. When Stalin reported the several contending points of view at the meeting and related how a compromise had been reached, he was telling the truth.

More than a year would pass before Bukharin’s trial. As late as June of 1937, after Bukharin had been in prison three months, Stalin told a meeting of military officers that although Bukharin and Rykov had “connections” to enemies, “we have no information [dannye] that he himself was an informer.”40 Even later in June, after Bukharin began to “confess” to the charges against him, it would be half a year before Stalin brought him to the dock.

Two-page protocol of the Central Committee Commission on the fates of Bukharin and Rykov, with edits and variations from Stalin’s proposal. 27 February 1937

Could it have been that Stalin put off destroying him for personal reasons? Although personal affection seems unlikely from such a calculating political monster, certainly treatment of no other repressed oppositionist was moderated so many times at Stalin’s initiative. Even after Bukharin’s arrest, his wife was allowed to live in her apartment in the Kremlin for several months. Stalin personally intervened to prevent her eviction. About the time Bukharin began to confess in the summer of 1937, she was given the option to live in any of five cities outside Moscow; she picked Astrakhan. Although according to Beria, Yezhov wanted to have her shot along with other “wives of enemies of the people,” Stalin refused.41 Ultimately, however, she spent many years in exile. There is no doubt that Stalin had instigated or authorized Yezhov’s campaign against the rightists. It could never have gone so far without Stalin’s continued support. But when and to what degree would Bukharin be destroyed? It is entirely possible that Stalin himself had not decided exactly what to do with Bukharin and Rykov. As we noted earlier, as long as these former lieutenants lived, Stalin’s political options remained open and the futures of his present lieutenants remained in doubt. By once again postponing a final decision on Bukharin, Stalin maintained the mystery about his true intentions, or even whether he had himself decided them.

Stalin’s position also maintained maximum flexibility. He had not publicly or wholeheartedly associated himself with Yezhov’s charges and had taken an almost neutral stance at the plenum; he gave Bukharin and Rykov unprecedented time to answer the charges, and in comparison with the other speakers, his demeanor seemed balanced and evenhanded. The minutes of the plenum’s deliberations on Bukharin and Rykov were never circulated even to senior regional party officials. Only those present knew what had been said, and given Stalin’s reticence and ambiguous stance, not even they were sure what he wanted. Even now, his proposal implied that the matter was not proved and needed to be checked further.

As in December 1936, his move to postpone implicitly cast doubt on Yezhov’s investigation to date, and it was not inconceivable that he could change course at any time. Indeed, at the end of 1938, Stalin would remove Yezhov, disavow his excesses, order the arrest of the purgers, and release a number of those “falsely arrested.” As long as Bukharin’s death did not have Stalin’s official stamp, as long as he postponed a decision, such a reversal was possible. Bukharin could be released and Yezhov and the purgers arrested. Stranger things could and did happen in this period.

Bukharin and Rykov were arrested at the plenum and sent to prison, yet it would be more than a year, March 1938, before they were brought to trial. For whatever reason, the Bukharin affair resembled the Yenukidze and Postyshev cases. In all three instances, the victims were personal friends of Stalin’s who were ultimately executed. But in each of these cases, the road to the execution cellar was characterized by hesitation and false starts directly attributable to Stalin. Even today, when we have a mass of revealing documents, the story remains unclear. As with any highly skilled politician, his maneuvers, his personal and political motives, remain hidden.