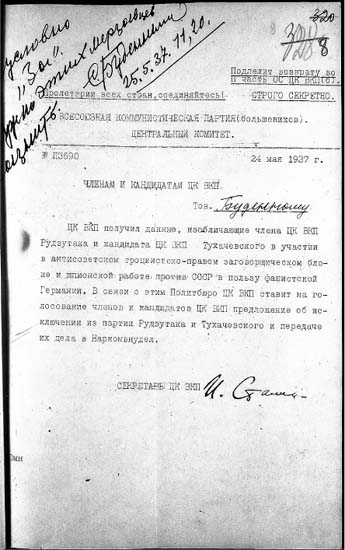

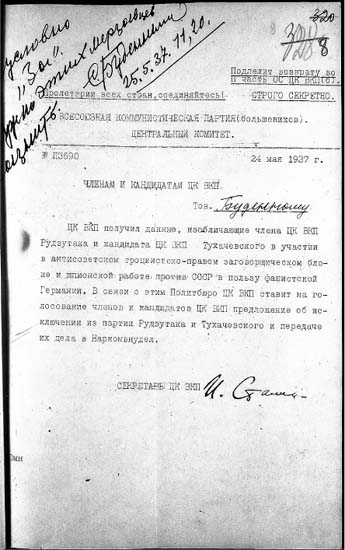

Politburo ballot to expel Tukhachevsky and Rudzutak from the party and send their cases to the police. Semen Budenny’s copy with his marginal note: “Unconditionally yes. It is necessary to finish off this scum.” 24 May 1937

All kulaks, criminals and other anti-Soviet elements subject to punitive measures are broken down into two categories: a) To the first category belong all the most active of the above-mentioned elements. They are subject to immediate arrest and, after consideration of their case by the troikas, to be shot.—NKVD Operational Order, 1937

We did not trust; that’s the thing.—V. M. Molotov

THE FEBRUARY–MARCH 1937 plenum also marked the beginnings of a purge of the police. Although Yezhov had taken over leadership of the NKVD from Yagoda the previous September, most of Yagoda’s senior deputies and appointees were still in place. These NKVD officials were professionals, having served in the police since the Civil War, and removing such people unceremoniously would be disruptive and politically difficult. Not only were they entrenched political players of the nomenklatura, but their removal could raise inconvenient questions: if Yagoda and company were to be directly branded as longtime incompetents (or worse), as was becoming the fashion, the long series of political persecutions and prosecutions (against Mensheviks, Trotskyists, kulaks, and other opponents) could be called into question. When Yagoda had been replaced, therefore, his political loyalty had not been disputed, and he had been given the position of Commissar of Communications. Removing such people was a delicate and high-level political decision requiring considerable preparation and “political education.”

Yezhov chose the February–March plenum as the venue for attack. The agenda contained the item “Lessons of the Wrecking, Diversion, and Espionage of the Japanese-German-Trotskyist Agents,” for which Yezhov was slated to give the main report, a denunciation of Yagoda’s management of the NKVD. Since the middle of 1936, when Yezhov had summoned NKVD Deputy Commissar Yakov Agranov to a “conspiratorial meeting,” Yezhov had been trying to turn Yagoda’s deputies against him.1 By early 1937 he had succeeded in “turning” several central and regional NKVD officials. In preparation for the attack he was to give at the plenum, this new “Yezhov group” within the police received special invitations to attend.2

Yezhov’s report attacked Yagoda’s leadership indirectly by focusing on the sins of his Deputy Molchanov, former chief of the Secret Political Department of the NKVD. The plenum unanimously approved a resolution closely based on Yezhov’s report.3 Yagoda attempted to defend himself by refuting the charges of lax leadership and by claiming that he had in fact taken the lead in investigating and arresting Trotskyists. One of Yezhov’s new followers, Leningrad NKVD chief Leonid Zakovsky, took the lead in attacking Yagoda and Molchanov: “We heard what I would consider a very incoherent speech by Comrade Yagoda, our former Commissar for Internal Affairs and I believe that the Plenum of the Central Committee of the Party cannot be satisfied with it. First of all, Comrade Yagoda’s speech contained many errors, very incorrect, inexact [assertions], and I would add, no political [assessment]. It is not true that Yagoda’s hands were tied and that he could not manage the apparat of state security.”4

Yakov Agranov had been named Yezhov’s deputy commissar of the NKVD in the same 1936 Politburo resolution appointing Yezhov, and Yezhov had used Agranov to undermine Yagoda for some time. Agranov had tried to work both sides of the street by implementing Yezhov’s directives in such a way so as not to offend Yagoda. He now came under attack for this ambiguity and did his best to defend himself.5

Comrades! It is absolutely clear that the old leadership of the NKVD has turned out to be incapable of managing state security.

The Central Committee of our Party acted wisely in placing Comrade Yezhov, Secretary of the CC of our Party, at the head of the NKVD.

The person to head the militant organ of the proletarian dictatorship ought to be someone invested with the full trust of the Party of Lenin and Stalin.

The appointment of Comrade Yezhov has cleared the air with its strong, bracing Party spirit.6

The attack on Yagoda had been strong, but inexplicable delays surround his downfall. At the end of the discussion, an especially aggressive member, I. P. Zhukov, called directly for Yagoda’s arrest. Zhukov was always trying to display his vigilance, and his attacks on Bukharin had been so wild as to elicit laughter from the plenum. Now he went beyond the script and had to be restrained:

ZHUKOV: Because this business needs to be investigated, and in order to investigate it, it is necessary to give instructions to the NKVD, to Comrade Yezhov. He will conduct the matter perfectly—(noise in the hall)

VOICE: I don’t understand. What is the proposal?

YEZHOV: Everybody is arrested.

ZHUKOV: Why not arrest Yagoda? (noise in the hall) Yes, yes. I am convinced that the matter will come to that.

KOSIOR: What is your proposal? (movement and noise in the hall)

VOICE: What is the proposal? It’s not necessary to agree to anything.7

Yagoda was neither expelled from the party nor arrested by the plenum. Yet one month later, the Politburo ordered this very thing. When that order was produced, the text contained a note of unusual urgency about arresting the former NKVD chief that seemed to contradict the plenum’s hesitation to take the step just a few weeks before. It is likely that in the intervening weeks, Molchanov and others from Yagoda’s circle had been arrested and forced to give testimony implicating their former boss in “criminal activities.”

Even after the decision was taken to expel and arrest Yagoda, there seems to have been some indecision. The expulsion order exists in two variants, the first a routine dismissal but the second (signed by Stalin) expressing the urgent need for his arrest: “The Politburo of the CC of the VKP(b) undertakes to inform the members of the CC of the VKP that, in view of the danger of leaving Yagoda at liberty for so much as one day, it is compelled to order his immediate arrest.”8 Even then, he was not dismissed from his position as commissar for communications for another week.9

In the days following Yagoda’s arrest, Yezhov began shifting around regional and central NKVD personnel in order to put his loyal followers into key positions. He also began a series of “mobilizations” of dependable cadres to staff the NKVD, drawing them from the ideological party schools.

The February–March plenum had written a new political transcript for the party. It had raised the level of “vigilance” against oppositionists and enemies to new heights and established the principle that the enemy was everywhere. It had also criticized the regional nomenklatura for not being vigilant enough to prevent infiltration by those enemies. These regional bosses were taken to task for bureaucratism, suppression of criticism, undemocratic practices, and paying too much attention to economic management.

In the precise texts of the plenum, these themes were discrete: the opposition was the enemy, but the cadres were just careless. The enemy had to be destroyed, but poor cadres should be retrained and indoctrinated. In the wake of the plenum, however, these themes began to blur together. Partly as a result of the new campaign of “criticism from below,” incompetent, abusive, or unpopular party leaders in the provinces were more and more often branded as enemies themselves. Carelessly tolerating the enemy became protecting the enemy. Suppression of the rank and file gradually became Trotskyist sabotage of party norms. Not catching a wrecker became wrecking. Reports on the February–March 1937 plenum to local organizations show the increasing paranoia and vigilance. The stated differences between Trotskyists and rightists and among various foreign enemies ran together in the popular mind, and there was now talk of “Japanese-German-Rightist-Trotskyists.”

That the regional party leaders were coming more and more under a cloud following the February–March 1937 plenum is clear from several events. On the basis of a speech by A. A. Zhdanov, the Central Committee ordered regional party leaders to stand for reelection in May. Heretofore, such elections had been purely a formality; balloting was not secret, and the regional leaders were able to keep their people in power because no one below was willing to oppose their candidates openly. This time, though, the rules were different. The elections were to be held by secret ballot, and it seems to have been the intention of the Moscow leaders to take advantage of rank-and-file party hostility to their local chiefs in order to control those chiefs “from below” with an election. If the party elections of May 1937 were meant to dethrone territorial party leaders, they were a failure. Although there was significant turnover in district and cell committees, the upper reaches of the regional party elite remained in office through the spring of 1937.10

A second, less publicized event was just as important. Another of the mechanisms that regional “family circles” had used to protect themselves was the inclusion of the local NKVD chief in the machine. Although nominally the provincial NKVD reported to Moscow, it was more often than not part of the local party group. As long as the long-serving NKVD chiefs remained in place, they tended to defend party leaders who were being criticized from below.11 There were few arrests of prominent local party machine members, and police persecution fell on ordinary people for minor offenses. In the spring of 1937 this began to change as Yezhov quietly replaced and transferred the existing provincial NKVD leaders. At the same time, party organizations inside the security services were transferred from the control of the territorial party committees to that of the police themselves, thereby detaching local NKVD officials from those committees.12

On 11 June 1937 the world was shocked by the Soviet press announcement that eight of the most senior officers of the Red Army had been arrested and indicted for treason and espionage on behalf of the Germans and Japanese. The list included the most well-known field commanders in the Soviet military: Marshal M. N. Tukhachevsky (deputy commissar of defense) and Generals S. I. Kork (commandant of the Frunze Military Academy), I. E. Yakir (commander of the Kiev Military District), and I. P. Uborevich (commander of the Belorussian Military District), among others. Arrested the last week of May, the generals were brutally interrogated by the NKVD and had “confessed” by the beginning of June. On 2 June a meeting of 116 high-ranking officers heard reports by Defense Commissar K. I. Voroshilov and Stalin on the case. At that meeting, Stalin said that “without a doubt a military-political conspiracy against Soviet power had taken place, stimulated and financed by German fascists.”13 On 12 June, at an expanded session of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court, all were convicted. They were shot on the same day.14 Yan Gamarnik, chief of the Political Administration of the Red Army, had committed suicide before he could be arrested.

We do not know why Stalin decided to decapitate the Red Army in 1937. Several possible elements may have contributed to the decision. First, Tukhachevsky and the other accused had frequently disagreed with Stalin’s loyal but incompetent minister of defense, Voroshilov, and on at least one occasion had openly insulted him. Second, rumors had reached Stalin from Europe (apparently along with disinformation documents from the German secret police) to the effect that Tukhachevsky and his group were disloyal. Third, relations between party and army in the Soviet system had always been rocky. From time to time, the party had appointed “political commissars” to watch over the officer corps; such political watchdogs had been installed just before the arrest of the generals.15Members of the Tukhachevsky group were not “party first, army second” personalities like Voroshilov, Semen Budenny, and others who had fought alongside Stalin in the Civil War. Finally, of course, the army was an armed, organized force that could conceivably challenge Stalin and the party regime for control of the country.

The officers had been under suspicion for some time. Both Stalin and Molotov had mentioned at the February–March plenum that it would be necessary to verify [proverit’] the military to weed out any enemies. The previous year, Yezhov had arrested and had questioned for months a few military officers who had been active Trotskyists at some time in the past. In the spring of 1937 the investigators had focused on securing testimony against Tukhachevsky and his circle. It seems that several things came together in April–May 1937: the possible receipt of the disinformation documents from Germany and the confessions of V. M. Primakov and other Trotskyist officers directly implicating Tukhachevsky.

There is reason to believe that military commanders doubted at first that the military plot was real. In early June, Stalin addressed a meeting of top military men and rather convincingly made the case for Tukhachevsky’s treason. In the course of his argument, he implied that there had been some doubts among military men that had to be cleared up: “Comrades, I hope that now nobody doubts that there was a military-political conspiracy against Soviet power.”16 In 1971 and 1975 V. M. Molotov admitted that many “mistakes” had been made in the repressions of the 1930s. But he doggedly insisted that of all the cases, that of Tukhachevsky and the generals had been clear: they were guilty of preparing a coup against Stalin. “Beginning in the second half of 1936 or maybe from the end of 1936 he was hurrying with a coup…. And it is understandable. He was afraid that he would be arrested…. We even knew the date of the coup.”17Both in public and in private, Stalin certainly acted as if he believed the military plot was real. In 1937, in private conversation with Georgi Dimitrov, head of the Communist International, Stalin said of the oppositionists, “We were aware of certain facts as early as last year and were preparing to deal with them, but first we wanted to seize as many threads as possible. They were planning an action for the beginning of this year. Their resolve failed. They were preparing in July to attack the Politburo at the Kremlin. But they lost their nerve—they said: ‘Stalin will start shooting and there will be a scandal.’ I would tell our people—they will never make up their minds to act, and I would laugh at their plans.”18

Given the discipline of the nomenklatura behind Stalin, the army had been the last force capable of stopping the arrests. Bukharin, under arrest since March, may have realized this. Just before his arrest, he apparently told his wife that the current leadership wanted to destroy the Old Bolshevik oppositionists for fear that if they came to power, they would destroy the Stalinist faction. He advised her that in the event of his arrest, she should flee the country with the help of the American diplomat William C. Bullit, who had promised to help.19 Later his wife was taunted by an NKVD interrogator: “You thought that Yakir and Tukhachevsky would save your Bukharin. But we work well. That’s why it didn’t happen.”20Nine days after the arrest of Tukhachevsky and Yakir, Bukharin wrote to Yezhov from prison and began to confess.21

May 1937, when the generals and several powerful civilian figures were arrested, represents a major watershed in the 1930s. This was the first time that large numbers of people were repressed who had never been overt oppositionists, and who had always sided with Stalin in the various party disputes. The new policy in the second half of 1937 was, essentially, to destroy anyone suspected of present or possible future disloyalty to the ruling Stalin group. As Molotov put it,

1937 was necessary…. We were obligated in 1937 [to ensure] that in time of war there would be no fifth column…. I don’t think that the rehabilitation [by Khrushchev] of many military men, repressed in 1937, was correct. The documents are hidden now, but with time there will be clarity. It is doubtful that these people were spies, but they were connected with spies, and the main thing is that in the decisive moment there was no relying on them…. If Tukhachevsky and Yakir and Rykov and Zinoviev in time of war went into opposition, it would cause such a sharp struggle, there would be a colossal number of victims. Colossal. And on the other hand, it would mean doom. It would be impossible to surrender, it [the internal struggle] would go to the end. We would begin to destroy everyone mercilessly. Somebody would, of course, win in the end, but on both sides there would be huge casualties.22

There is no evidence that the accused officers were involved in any plot against Stalin, despite rumors to the contrary.23 Yet the regime acted as if leaders believed that there was a plot, or at least as if they feared retaliation from some corner. All the officers were arrested in transit, secretly, away from their commands. Tolerating no delay, Yezhov’s investigators tortured the officers mercilessly until they confessed. Analysis many years later showed that there were bloodstains on the confession signed by Tukhachevsky.24 On the day of the trial investigators were still beating confessions out of the accused, who were shot immediately after sentencing. Unlike the long delays with Bukharin and some others, this was a Stalin-Yezhov coup that was presented to the country as a fait accompli.

The laconic party documents marking their party expulsion do not capture the drama and brutality of the event: “The Central Committee has received information implicating CC Member Rudzutak and CC Candidate Member Tukhachevsky in participation in an anti-Soviet Trotskyist-Rightist conspiratorial bloc and in espionage work against the USSR on behalf of fascist Germany. In connection with this, the Politburo of the CC VKP(b) puts to a vote to members and candidate members of the CC VKP(b) the proposal to expel Rudzutak and Tukhachevsky from the party and transfer their cases to the NKVD.”25

The archives are filled with such documents, each legally required in order to expel a Central Committee member from the party before arrest. Clearly, though, it is legalism at work here and not legality. First, Rudzutak and Tukhachevsky were no longer referred to as “comrade” in the document proposing their expulsion. Procedures required referring to them as “comrades” up to the time of their official expulsion from the party. Second, this action was taken before any trial or formal accusation, or even before the “information” could be evaluated. In the atmosphere of 1937, simply “receiving information” was enough for the Politburo to seal one’s fate. As was always the case in 1937, every member and candidate member of the Central Committee once again held to nomenklatura discipline and voted in favor of the resolution. Even Lenin’s widow, Krupskaia, who sometimes qualified her vote by answering “agreed” rather than “for,” voted “for” in this case.26

Politburo ballot to expel Tukhachevsky and Rudzutak from the party and send their cases to the police. Semen Budenny’s copy with his marginal note: “Unconditionally yes. It is necessary to finish off this scum.” 24 May 1937

In the ten days following the death of Tukhachevsky, 980 senior commanders were arrested. Many were tortured and shot. In the coming months the Soviet military establishment was devastated by arrests and executions. In 1937, 7.7 percent of the officer corps were dismissed for political reasons and never reinstated; in 1938 another 3.7 percent were removed. In 1937 and 1938, according to the latest estimates, more than 34,000 military officers were discharged for political reasons. Of these, 11,596 were reinstated by 1940, leaving the fate of more than 22,000 officers unknown; they either were arrested or retired.27 In the wake of Stalin’s coup against the military, special service was duly rewarded, and on 24 July, Yezhov received the Order of Lenin “for outstanding success in leading the organs of the NKVD in the implementation of government assignments.”28

The fall of the generals triggered an explosion of terror nationwide directed at leading cadres in all fields and at all levels. In the second half of 1937, most people’s commissars (ministers), nearly all regional first party secretaries, and thousands of other officials were branded as traitors and arrested. The majority of these high-ranking officials seem to have been shot in 1937–40.29 Several times per week throughout 1937, NKVD chief Yezhov forwarded to Stalin interrogation transcripts in which senior officials confessed to treason and named their fellow “conspirators.” In nearly all cases, Stalin ordered the arrest of those named.30

Stalin had finally decided. If there had been indecision in the previous period about repression of some leaders, there was none now. If Stalin had seemed neutral or less than enthusiastic about repressing certain people, after the fall of the generals his name is all over the documents authorizing the terror. As usual, the remaining members of the CC voted unanimously for the proposed expulsions from the party:

The CC of the VKP(b) declares its lack of political confidence in Comrades Alekseev, Liubimov, Sulimov, members of the CC of the VKP(b), and in Comrades Kuritsyn, Musabekov, Osinsky and Sedelnikov, candidate members of the CC of the VKP(b), and hereby decrees:

That Comrades P. Alekseev, Liubimov and Sulimov be expelled from membership in the CC of the VKP(b) and that Comrades Kuritsyn, Musabekov, Osinsky and Sedelnikov be expelled from candidate membership in the CC of the VKP(b).

Re: Antipov, Balitsky, Zhukov, Knorin, Lavrentev, Lobov, Razumov, Rumiantsev, Sheboldaev, Blagonravov, Veger, Goloded, Kalmanovich, Komarov, Kubiak, V. Mikhailov, Polonsky, N. N. Popov, Unshlikht, Aronshtam, Krutov.

Politburo ballot tally on expulsion of K. Ukhanov, with Lenin’s widow voting “agreed” instead of “for.” 20 May 1937

The following motion by the Politburo of the CC is to be confirmed.

The following persons are to be expelled for treason to the Party and motherland and for active counter-revolutionary activities:

[a] Antipov, Balitsky, Zhukov, Knorin, Lavrentev, Lobov, Razumov, Rumiantsev and Sheboldaev are to be expelled from membership in the CC of the VKP(b) and from the Party;

[b] Blagonravov, Veger, Goloded, Kalmanovich, Komarov, Kubiak, V. Mikhailov, Polonsky, N. N. Popov and Unshlikht are to be expelled from candidate membership in the CC of the VKP(b) and from the Party;

[c] Aronshtam and Krutov are to be expelled from membership in the Central Inspection Commission and from the Party.

[d] The cases of the above-mentioned persons are to be referred to the NKVD.

In view of incontrovertible facts concerning their belonging to a counterrevolutionary group, Chudov and Kodatsky are to be expelled from membership in the CC of the VKP(b) and from the Party, and Pavlunovsky and Struppe are to be expelled from candidate membership in the CC of the VKP(b) and from the Party.31

This first list of Central Committee expulsions in June had included several leading regional party secretaries, including Rumiantsev from Smolensk, Sheboldaev from Kursk, and Chudov and Kodatsky from Leningrad. By the end of 1937 nearly all of the eighty regional party leaders had been replaced, including those of the union republics. Frequently they were blamed for economic and agricultural failures that occurred in 1936–37.32

Because expelling and removing a regional party secretary formally required a vote from his party organization, and because Stalin wished to mobilize rank-and-file party members against the midlevel leadership, these removals were conducted in a specific way. A high-ranking Politburo emissary was dispatched from Moscow to the provincial capital with instructions to “verify” the party leadership. A plenum of the regional party committee was called, with the emissary putting forward the charges against the regional leader and “his people.” Typically, the local first secretary would speak (if he was still at liberty), then members of the local party committee would be unleashed to denounce their leader (which was now safe, in the presence of a big Moscow man), and finally the local leader would then be removed.33

For example, between June and September 1937, A. A. Andreev traveled to Voronezh, Cheliabinsk, Sverdlovsk, Kursk, Saratov, Kuibyshev, Tashkent, Rostov, and Krasnodar to remove the territorial leaderships.34At each stop, he was in telegraphic communication with Stalin, relaying to him the results of the plenums and the opinions of the local party members. Frequently Andreev recommended expelling and arresting the local leadership, and Stalin always approved these requests:

Telegram from I. V. Stalin to A. A. Andreev in Saratov

The Central Committee agrees with your proposal to bring to court and shoot the former workers of the Machine Tractor Stations.

Stalin

28 July 193735

The language used in both the reports and the replies indicates that both Andreev and Stalin actually believed they were uprooting real treason. In some cases, the matter was more doubtful, and Stalin proposed simply removing the regional secretary and sending him to Moscow, where, in almost all cases, he would be arrested.36

On several occasions, Andreev was accompanied by a central NKVD official to carry out the necessary arrests. In several places, Andreev told Stalin that the former local party leadership, through its control of the local NKVD, had arrested large numbers of innocent people. In Saratov, Andreev reported that the former ruling group had dictated false testimony for the signatures of those arrested; he blamed it on the “Agranov gang” within the NKVD. In Voronezh, Andreev complained that “masses” of innocent people had been expelled and arrested. With Stalin’s approval, Andreev organized special troikas to review these cases—six hundred in Voronezh alone—and release those arrested by the now-condemned former leadership.37

The campaign for vigilance was now out of control, with officials at all levels denouncing each other and encouraging arrests to protect themselves. At the June 1937 plenum of the Central Committee, Yezhov gave an amazing speech in which he announced the discovery of a grand conspiracy that united leftists, rightists, Trotskyists, members of former socialist parties, army officers, NKVD officers, and foreign communists. This “center of centers,” he said, consisted of thirteen discrete “anti-Soviet organizations” that had seized control of the army, military intelligence, the Comintern, and the commissariats of Foreign Affairs, Transport, and Agriculture. He claimed that the conspiracy had representatives in every provincial party administration and was thoroughly saturated with Polish and German spies. The Soviet government was said to be hanging by a thread.38

The archives currently available to us provide little in the way of personal correspondence between key leaders. Such private, hidden transcripts would provide important clues about the correlation between what the Stalinists said in public and what they confided to each other. The examples we do have, however, strongly suggest that there was little difference between the Stalinist leaders’ private thoughts and public positions. It is, of course, difficult to know the inner thoughts of the top leaders about the degree of guilt of those they destroyed. But if their private correspondence is any gauge, they seem really to have believed in the existence of a far-flung conspiracy.

Stalin and Molotov took a personal hand in whipping up the hysteria. On several occasions they not only signed long lists of people to be shot but also encouraged terror in the provinces. Stalin wrote a series of circular letters containing passages like the following:

I consider it absolutely necessary to politically mobilize members of the kolkhozy for a campaign aimed at inflicting a crushing defeat on enemies of the people in agriculture. The CC of the VKP(b) orders the provincial committees, the territorial committees and the CCs of the national Communist parties to organize, in each district of each province, two or three public show trials of enemies of the people/agricultural saboteurs who have wormed their way into district Party, Soviet and agricultural. These trials should be covered in their entirety by the local press.39

With the aim of protecting the kolkhozy and sovkhozy from the sabotage of enemies of the people, the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR and the CC of the VKP(b) have decided to crush and annihilate the cadres of wreckers in the field of animal husbandry….

With this aim in mind, the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR and the CC of the VKP(b) propose that 3 to 6 open show trials be organized in each republic, region and province, that the broad masses of peasants be involved in them and that the trials be widely covered in the press.

All persons convicted of sabotage are to be sentenced to death by execution, and reports of these executions are to be published in the local press.40

In the fall of 1937 the decimation of the Central Committee continued, with Stalin showing no hesitation or indecision:

Plenary Session of the Central Committee

11–12 October 1937

Comrade Stalin has the floor.

STALIN: The first question concerns membership in the CC. During the period between the June Plenum and the present Plenum several members of the CC were removed from the CC and arrested: Zelensky, who turned out to be a Tsarist secret police agent [okhrannik], Lebed’, Nosov, Piatnitsky, Khataevich, Ikramov, Krinitsky, Vareikis—all together 8 persons. Examination and verification of all available materials have shown that these people are all enemies.

If there are no questions [from the floor], I would like the Plenum to take this information under advisement.

VOICES: That’s right. We have taken it under advisement.

STALIN: In addition, during this same period 16 persons were removed from the CC as candidate members and arrested: Grinko, Liubchenko,—who shot himself to death, Yeremin, Deribas,—who turned out to be a Japanese spy, Demchenko, Kalygina, Semenov, Serebrovsky,—who turned out to be a spy, Shubrikov, Griadinsky, Sarkisov, Bykin, Rozengol’ts,— who turned out to be a German-English-Japanese spy.

VOICES: Wow!

STALIN: Lepa, Gikalo and Ptukha—all together 16 persons. An investigation and verification of materials available showed that these people [the 16 persons above] were also enemies of the people. If there are no questions or objections [from the floor], I would like for the Plenum to take this information also under advisement.

VOICES: Let’s approve it.

ANDREEV: There is a motion on the floor to approve the Politburo’s proposal. Any objections?

VOICES: None.

ANDREEV: (voting) Adopted unanimously.41

As had always been the case, the members of the Central Committee quickly and, as a group, suicidally voted unanimously each time to expel those designated as enemies.42 These arrests of Central Committee members proceeded over more than a year’s time. At no point was it clear to anyone how far the process would go; each member at a given moment probably thought that despite the spreading arrests, he was not an enemy and was therefore safe. As the episode was recalled in 1975,

MOLOTOV: In the first place, on democratic centralism … Listen, it did not happen that a minority expelled a majority. It happened gradually. 70 expelled 10–15 people, then 60 expelled another 15. All in line with majority and minority.

CHUEV: This indicates an excellent tactic but it doesn’t indicate rectitude.

MOLOTOV: But permit me to say that it corresponds with the factual development of events, and not simply tactics. Gradually things were disclosed in a sharp struggle in various areas. Someplace it was possible to tolerate: to be restrained even though we didn’t trust [someone]. Someplace it was impossible to wait. And gradually, all was done in the order of democratic centralism, without formal violation. Essentially, it happened that a minority of the composition of the TsK remained of this majority, but without formal violation. Thus there was no violation of democratic centralism, it happened gradually although in a fairly rapid process of clearing the road.43

Finally, there was the strong pull of party tradition and democratic centralism, the feeling that the nomenklatura had to remain unified, to hang together even as they were hanging separately. In the name of party unity and with a desperate feeling of corporate self-preservation, the nomenklatura committed suicide. They also contributed to their own destruction by pushing things in the direction of mass terror.

We have seen that various leaders had tried to protect themselves by ordering mass expulsions and arrests of rank-and-file party members. In turn, the rank and file denounced their bosses as enemies. It was a war of all against all, with intraparty class and status overtones. As an unrepentant Molotov later recalled, “In our system, if you conducted some kind of campaign, you conducted it to the end. And all kinds of things can happen when everything is on such a scale.”44

From mid-1937 to nearly the end of 1938, the Soviet secret police carried out a mass terror against ordinary citizens. These “mass operations,” as they were called, accounted for about half of all executions during the “Great Purges” of 1937–38. By the time it ended in November 1938, 767,397 persons had been sentenced by summary troikas; 386,798 of them to death and the remainder to terms in GULAG camps.45 Other “mass operations” in 1937–38 targeted persons of non-Soviet citizenship or national heritage, including Poles, Germans, Latvians, Koreans, Chinese, and others, accounting for an additional 335,513 sentences (including 247,157 executions).46 The process included systematic, physical tortures of a savage nature and scale, fabricated conspiracies, false charges, and mass executions. As such, the operations of 1937–38 must be counted among the major massacres of a bloody twentieth century.

Since the 8 May 1933 decree discussed above, the trend had been to reduce mass campaigns of political repression, and a variety of official statements by Stalin and Yezhov denounced mass operations. Such mass campaigns were unleashed rather than administered, heavy-handed and blunt instruments that frequently damaged rational policy planning (and Stalin’s power) as much as they accomplished his goals. For Stalin, operating in campaign mode meant ceding central control, inviting chaos, and trusting the fate and reputation of the regime to far-off local authorities. When sufficient progress had been made, or when things had gone too far, it was necessary to restore order and rein in the chaos, and much of prewar Stalinist history is told in the flow and ebb, the launching and restraining of campaigns. Thus, for example, cleaning up the “campaign justice” of the collectivization period and restoring centralized order required checking the power of local political officials.47

Mass operations in 1933–36 were on a dramatically reduced scale, not comparable with those of the preceding period. According to secret police data, arrests for “counterrevolutionary insurrection” (a common charge in mass operations, including the subsequent kulak operation) fell from 135,000 in 1933 to 2,517 in 1936.48 Despite the continuation of certain restricted mass operations, the era of mass repression seemed clearly on the wane. If Stalin had been trying to curb inefficient “mass operations,” why then did he suddenly resort to them in the middle of 1937?

At that time, the Moscow leadership became afraid of threats in the countryside. In 1936 the USSR had adopted a new constitution that authorized the election of a new legislature, the Supreme Soviet. In June 1937 the Central Committee prescribed electoral procedures to enfranchise the entire adult population—including previously disenfranchised groups like former White officers, tsarist policemen, and kulaks—in a system of secret-ballot elections. These elections, according to the June 1937 decree, would be for contested seats, with multiple candidates campaigning. Local party leaders were horrified at Stalin’s democratic experiment and complained to Moscow that the proposed Supreme Soviet elections were giving new hope and life to various anti-Bolshevik “class enemies” who sought to use the electoral campaign to organize legally.49 Regional party and NKVD leaders bombarded Moscow with stories of counterrevolutionary and “insurrectionary” groups taking shape in the countryside: returning kulaks and other “anti-Soviet elements” encouraged by the possibility of free elections.50

At the February 1937 CC plenum, regional party secretaries made a careful protest. Breaking with tradition, none of them signed up to speak in the discussion of A. A. Zhdanov’s report on democratic elections. Normally, at the conclusion of a main report to a Central Committee plenum, speakers would register with the presidium to speak in the “discussion.” Typically, that discussion repeated the main points of the report and praised the speaker for proposing “absolutely correct” solutions. But when Zhdanov finished speaking about “party democracy,” nobody registered or rose to speak. This had not happened in many years. A. A. Andreev, chairing the meeting, announced in despair, “I don’t have anyone registered. Somebody has to register.” Regional secretary Robert Eikhe, of Western Siberia, whined, “I can’t; I’m not ready. I will speak tomorrow.” M. F. Shkiriatov wryly noted, “The orators have to prepare themselves.” Stalin pressed for someone to say something: “We need [at least] a provisional conclusion.” Finally, E. M. Yaroslavsky spoke up, “I ask to be registered.” A delighted and relieved Stalin said, “There! Yaroslavsky!”51

Head of the League of the Militant Atheists, Yaroslavsky then held forth on religion. Zhdanov’s speech had mentioned the weakness of anti-religious propaganda only in passing, as a typical failure of party work. But Yaroslavsky’s remarks gave the party secretaries a chance to complain about their problems in the countryside and to warn of the danger of the new electoral system, all in the context of “discussing” Zhdanov’s speech (which, according to accepted formula, they nevertheless praised). Party secretaries had already blamed shortcomings in their regions on “contamination” (zasorenie) by anti-Soviet elements.52 They now warned that the new electoral system gave anti-Soviet elements—religious and political— “new possibilities to harm us” and would encourage attempts by enemies to “conduct attacks against us, to organize a struggle against us.”53 S. V. Kosior complained that thousands of religious believers were attending religious-political “events” to cynically praise Stalin for their new rights. Kosior went on to complain of “awful wildness, conservatism … fanatical religious sentiments that feed undisguised hatred of Soviet power.”54

One noted that “We have a series of facts that harmful elements from the remnants of the former kulaks and clergy, especially mullahs, are conducting work among remnant groups and preparing for the elections…. It is clear that it is necessary to carry out a decisive struggle against these elements.”55 Another observed that “kulak elements, priests, sons of priests, sons of [tsarist] policemen … according to the new Constitution received electoral rights. They can vote. It seems to me that here we have to pay particular attention to the changes arising in the population which have gone on in each province.”56

At CC plenums and in private correspondence, regional party leaders made plain their fear of and opposition to contested elections in the countryside. The dangerous idea of contested elections remained in force. But two weeks after the fall of the military leaders, as the arrests began to consume the middle and upper ranks of the party leadership, Stalin began grudgingly to hear the regional arguments about losing whatever control of the countryside they enjoyed to mysterious, hidden, “anti-Soviet elements.”

Stalin needed local officials, even annoying and disobedient ones, to represent the regime and implement its policies out in the country. He needed to give them enough autonomy to do this, but without enough leeway to escape his authority or to go out of control and discredit the regime as a whole.57 Implicitly or explicitly, he had to negotiate with them. Despite his elevation to semidivine status, he had to listen to their views and take their needs into account. These regional “feudal princes” or “red princes,” as one scholar has called them, formed a cohesive interest group whose interests often contradicted Stalin’s.58

After a series of disturbing reports from the provinces about “insurrectionary” organizations, on 28 June, Stalin and the Politburo finally approved a request from Robert Eikhe, the first secretary of the Western Siberian Territory (and the one who had pointedly refused to speak in support of Zhdanov’s electoral ideas), to form an emergency troika with the right to pass death sentences.59 In what would become a model for future troikas, it consisted of the heads of the provincial NKVD, party, and procuracy.60 Four days later, eager to regularize, systematize, and control the procedure, Stalin sent a telegram to all provincial party and police agencies ordering the formation of troikas in each province with systematic reporting to him in Moscow.61

But Stalin was not yet willing to retreat from contested elections. He and his lieutenants continued to exhort regional party chiefs to campaign, to use propaganda to win the elections. And on 2 July 1937 Pravda no doubt disappointed the regional secretaries by publishing the first installment of the new electoral rules, officially enacting and enforcing contested, universal, secret-ballot elections.62

But Stalin now offered a compromise. The day the electoral law that so disturbed the regional leaders was published, the Politburo approved the launching of a mass operation against precisely the elements the local leaders had complained about, and hours later Stalin sent his telegram to provincial party leaders approving the formation of the lethal troikas.63 It is hard to avoid the conclusion that in return for forcing the local party leaders to conduct an election, Stalin chose to help them win it by giving them license to kill or deport hundreds of thousands of “dangerous elements.”64

Contemporaries immediately saw the link between the elections and the mass operations. Jailhouse informers in Tataria reported that those arrested in the mass operations thought that the Bolsheviks were afraid of the elections and had launched a preemptive strike out of concern that enemies would seize control of the voting in the districts.65 Nikolai Bukharin, who was better placed to judge such things, praised mass terror in a letter to Stalin, noting that a general purge was in part connected with “the transition to democracy.”66 Three months later, in October, speakers at a Central Committee plenum would respond to Molotov’s report on electoral preparations with comments on the mass operations. First Secretary Kontorin of Arkhangelsk said, “We asked and will continue to ask the Central Committee to increase our limits for the first category [executions] in connection with preparations for the elections.”67

The Politburo therefore launched the “mass operations” of 1937–38 under pressure from regional party secretaries who feared the open elections. Many local officials may have been at least as quick to turn to repression as their boss in Moscow. It is not difficult to imagine that in 1937, local party leaders, fearful that they might be accused as “enemies of the people” in the spiraling terror of that year, would have found it convenient to launch repressive campaigns against others in order to deflect the witch hunt’s heat away from themselves. Provincial party secretaries faced the brunt of anti-Bolshevik resistance on the ground, while trying to respond to unmeetable demands from Moscow on everything from agricultural deliveries to industrial production to construction to dissemination of propaganda. In the political space they inhabited, some of them may have found it easier to crush categories of people with “administrative-chekist” methods than to convince them with “political work,” regardless of Moscow’s current policy. For local leaders persecution was “a tool of rural administration.”68 In the Stalinist system, regional officials were not timid or liberal politicians, with the population’s interests always at heart.69

Although it is clear that before June 1937 Stalin was not promoting mass operations, once he approved them he was determined to control them. A few days after his telegram, NKVD order no. 447 prescribed the summary execution of more than fifty-five thousand people who had committed no capital crime and were to be “swiftly” judged by extralegal organs without benefit of counsel or even formal charge. Their “trials” were to be purely formal; these victims were “after consideration of their case by the troikas, to be shot.” An extract of the troika’s minutes would form the only “legal” basis for the execution. Limits were established for each regional quota, and increases had to be approved by the Politburo. Although Stalin and Yezhov would approve almost all regional requests for increased execution limits, it is significant that these were in fact limits and not quotas. Not trusting the local party leaders to avoid hysterical massacres, Stalin was most determined to retain control over the operation.

Almost anyone could fall under one of the categories of victims: those committing “anti-Soviet activities,” those in camps and prisons carrying out “sabotage,” criminals, people whose cases were “not yet considered by the judicial organs,” family members “capable of active anti-Soviet actions.” It is also significant that round-number limits were established, with victims to be chosen by local party, police, and judicial officials according to their own lights. These limits do not correlate exactly with population; they rather seem to reflect a focus on sensitive economic areas where the regime believed the concentration of “enemies” to be the greatest, or where in previous trials and campaigns the greatest number of oppositionists had been unmasked. The regime was lashing out blindly at suspected concentrations of enemies.

This “operation,” which would be extended into the next year, represented a reversion to the combative methods of the Civil War, when groups of hostages were taken and shot prophylactically or in blind retaliation. It also recalled the storm of dekulakization in 1929, when the regime was also unable to specify exactly who was the enemy and lashed out with mass deportation.70 The new Red Terror of 1937, like its predecessors, reflected a deep-seated insecurity and fear of enemies on the part of the regime as well as an inability to say exactly who was the enemy, hence the round-number limits. Stalin and his associates knew there was opposition to the regime, feared that opposition (as well as their own inability to concretely identify or specify it), and decided to lash out brutally and wholesale. In this sense, the new Red Terror was an admission of the regime’s inability to govern the countryside efficiently or predictably, or even to control it with anything other than periodic bursts of unfocused violence.

At first glance, it is perhaps surprising that the authors of this massacre would commit their plans to writing and would preserve the document in archives for future historians to find. On the other hand, the Bolshevik leadership believed they were right to “clean” the country of “alien elements.” Although, as in the similarly worded documents on the mass executions of Polish officers in 1940, they never publicly stated what they had done, they were not afraid to create a text about their decision. They were not ashamed of what they were doing. In true bureaucratic fashion, a text, albeit a secret one, was produced: personnel, budgetary appropriations, and transportation were specified. The supplement to this document shows how this terror was administered according to the Bolsheviks’ vision of economic rationality, and the text that follows is surely one of the most chilling documents in modern history:

OPERATIONAL ORDER

of the People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs of the USSR. No. 00447 Concerning the punishment of former kulaks, criminals and other anti-Soviet elements.

30 July 1937. City of Moscow

It has been established by investigative materials relative to the cases of antiSoviet formations that a significant number of former kulaks who had earlier been subjected to punitive measures and who had evaded them, who had escaped from camps, exile and labor settlements have settled in the countryside. This also includes many church officials and sectarians who had been formerly put down, former active participants of anti-Soviet armed campaigns. Significant cadres of anti-Soviet political parties (SR’s, Georgian Mensheviks, Dashnaks, Mussavatists, Ittihadists, etc.) as well as cadres of former active members of bandit uprisings, Whites, members of punitive expeditions, repatriates and so on remain nearly untouched in the countryside. Some of the above-mentioned elements, leaving the countryside for the cities, have infiltrated enterprises of industry, transport and construction. Besides, significant cadres of criminals are still entrenched in both countryside and city. These include horse and cattle thieves, recidivist thieves, robbers and others who had been serving their sentences and who had escaped and are now in hiding. Inadequate efforts to combat these criminal bands have created a state of impunity promoting their criminal activities. As has been established, all of these anti-Soviet elements constitute the chief instigators of every kind of anti-Soviet crimes and sabotage in the kolkhozy and sovkhozy as well as in the field of transport and in certain spheres of industry. The organs of state security are faced with the task of mercilessly crushing this entire gang of anti-Soviet elements, of defending the working Soviet people from their counter-revolutionary machinations and, finally, of putting an end, once and for all, to their base undermining of the foundations of the Soviet state. Accordingly, I therefore ORDER THAT AS OF 5 AUGUST 1937, ALL REPUBLICS, REGIONS AND PROVINCES LAUNCH A CAMPAIGN OF PUNITIVE MEASURES AGAINST FORMER KULAKS, ACTIVE ANTI-SOVIET ELEMENTS AND CRIMINALS….

II. CONCERNING THE PUNISHMENT TO BE IMPOSED ON THOSE SUBJECT TO PUNITIVE MEASURES AND THE NUMBER OF PERSONS SUBJECT TO PUNITIVE MEASURES.

1. All kulaks, criminals and other anti-Soviet elements subject to punitive measures are broken down into two categories:

a) To the first category belong all the most active of the above-mentioned elements. They are subject to immediate arrest and, after consideration of their case by the troikas, to be shot.

b) To the second category belong all the remaining less active but nonetheless hostile elements. They are subject to arrest and to confinement in concentration camps for a term ranging from 8 to 10 years, while the most vicious and socially dangerous among them are subject to confinement for similar terms in prisons as determined by the troikas….

IV. order for conducting the investigation.

1. Investigation shall be conducted into the case of each person or group of persons arrested. The investigation shall be carried out in a swift and simplified manner. During the course of the trial, all criminal connections of persons arrested are to be disclosed.71

Unlike previous identifications of enemies, which often took the form of filling various symbols (Trotskyist, rightist) with new content, this operation was simply a mass killing not of categories (however attributed or defined) but of vague opponents. Without negotiating or defining who was to be involved, the operation sought to remove clumsy statistical slices of the population of each province. It was not targeting of enemies, but blind rage and panic. It reflected not control of events but a recognition that the regime lacked regularized control mechanisms. It was not policy but the failure of policy. It was a sign of failure to rule with anything but force.

Based on the sources now available (which are probably incomplete) we can say that with order no. 447 plus subsequent known limit increases, Moscow gave permission to shoot about 236,000 victims. We are fairly certain that some 386,798 persons were actually shot, leaving more than 150,000 shot without currently documented central sanction either from the NKVD or the Politburo.72 The possibility exists that local authorities went far beyond the permitted limits, especially when it came to shooting victims. In Turkmenistan, for example, where we happen to have full data on all approvals, we know that the Politburo approved 3,225 executions, but local authorities shot 4,037, an excess of 25 percent over approved limits.73 In Smolensk, archival research shows an approved limit of 4,000, but local authorities are known to have shot 4,500 and continued shooting victims even after a November 1938 decision ordering them to stop. They simply backdated the paperwork and continued shooting.74 Some regional party chiefs were enthusiastic about the mass operations. First Secretary Simochkin in Ivanovo liked to watch the shootings and was curious about why some of his subordinates chose not to.75 In Turkmenistan, First Secretary Chubin was so involved with the mass killings that in 1938 he tried to secure the recall of a new NKVD chief sent to stop them.76

All in all, the kulak operation of 1937–38 was hardly a model of planned efficiency, and the center’s detailed orders were often disregarded. Soon after the operation began, it was necessary for Moscow NKVD chiefs to issue more telegrams clarifying procedures.77 According to order no. 447, the operation was to begin with those to be executed, followed by a second stage encompassing those to be sent to camps. In the event, regional troikas sentenced victims to both categories simultaneously.78 Order no. 447 had forbidden the persecution of families of those arrested; in the event, troikas did this frequently.79 In fact, almost every restriction order no. 447 had placed on local conduct of the operation was violated in its implementation. Given that local authorities decided how many would be repressed, who would live, and who would die, it is difficult to agree that everything was “administered” from Moscow. Senior NKVD official Stanislav Redens said at a January 1938 NKVD conference, perhaps with some resignation, that the Moscow NKVD was able to give only “general directions” because regional secret police organizations acted “independently.”80

The operation lasted not the mandated four months but fifteen, and in some places the shootings continued after the 17 November 1938 orders halting them and insisting on procuratorial sanction for all arrests.81 More than a week after that, Yezhov’s successor L. P. Beria was still issuing decrees to local NKVD offices to “immediately stop all mass operations” and repeating the strictures of the 17 November 1938 orders limiting the NKVD to individual arrests with procuratorial sanction.82 Fully six months after that, USSR Procurator Vyshinsky complained to Stalin and Molotov that the NKVD still made arrests without that sanction.83

This was certainly a blind terror. Like a psychotic mass killer who begins shooting in all directions, the Stalinist center had little idea who would be killed. It opened fire on vague targets, giving local officials license to kill whomever they saw fit. The opposite of controlled, planned, directed fire, the mass operations were more like blind shooting into a crowd. The Stalinist regime resembled not so much a disciplined army as a poorly trained and irregular force of Red Cavalry, and the aftermath resembled the chaos of a battlefield, where the casualties bore only accidental resemblance to the originally intended victims both in number and type.

It is tempting to see the mass operations as part of a Stalinist plan for population policy or social engineering on a vast scale. Going beyond the modernist state’s usual efforts to map, standardize, and enumerate society in order to control it, “authoritarian high-modernist states,” to use James Scott’s terminology, take the next step and use large-scale, concerted force to impose “legibility, appropriation, and centralization of control.”84 Seen this way, the mass operations would be a deliberate “modernist” attempt to cultivate society by weeding out or excising alien or infected elements by killing them or removing them permanently from the body social.

On the other hand, as we have seen, the mass operations were unplanned, ad hoc reactions to a perceived immediate political threat. Rather than a thought-out policy, modernist or otherwise, they recalled instead the Civil War reflex: a violent recourse to terror—hostage taking and mass shootings—in the face of an enemy offensive. Indeed, they interrupted the ongoing policy of judicial reengineering. Despite the detailed operational plan (which was, of course, drawn up at the last minute and promptly ignored), the mass operations were more spasm than policy, and too imprecise and locally arbitrary in their targets to constitute centralized social engineering.

Derailing existing policy on judicial reform and modernization that the regime had cultivated since 1933, the operations illustrate the unpredictability and incoherence of the Stalinist system. Unable to plan or to efficiently carry out any kind of operation, the Stalinists quickly issued detailed instructions that just as quickly became meaningless in the chaos of the campaign.85 This was an operation in which central directives were violated or ignored and which left local officials in control. An anticipated four-month operation against escaped kulaks became a fifteen-month massacre of a wide variety of locally and randomly identified targets. The final result bore almost no relation to Stalin’s original directive, and descriptions like “centralization” and “planning” seem inappropriate to characterize such a system.

We can only speculate about the ultimate reasons for the mass terror of 1937. Scholars have long thought that it flowed from Stalin’s desire to preempt any possible “fifth column” behind the lines of the coming war.86However, the major steps in the terror do not chronologically match escalations in foreign policy or war scares in the 1930s, and as we have also seen, fear that opposition in the countryside was reaching dangerous levels played a role. It was a purely domestic event (the 1937 electoral campaign) that sparked the mass terror. Much of Bolshevik policy was governed by their fears of opposition large and small.87 It is not difficult to imagine that their paranoia could lead them to launch mass terror from fear of losing control of the countryside, as various anti-Soviet elements used the electoral campaign to organize themselves, spread their views, and spawn dangerous rumors. The foreign and domestic explanations are not mutually exclusive, and Stalin may well have seen the threatening opposition in the countryside as the seeds of wartime opposition.

Moreover, the genesis and development of these operations point to the importance of the structure of the system to an understanding of events. These terror campaigns had constituencies behind them outside of Moscow that saw them as suitable tools of Bolshevik administration. The documents we now have indicate a kind of dialectical relation between Stalin and peripheral officials in the mass terror operations. It is clear that to understand that system as a whole we must include the regional politicians’ (in this case suicidal) role, which, in this case, seems to have been more than simple obedience or posing as more royalist than the king. Local authorities had their own interests that did not always coincide with Moscow’s, and the relationship between center and periphery is crucial to the functioning (and dysfunction) of the system. It seems important “to examine the dictatorship as well as the Dictator.”88

We have seen that there is good reason to believe that the nomenklatura, the regional party officials, turned to violence sooner than Stalin did when it came to mass operations. Accordingly, they bear much of the responsibility for the general escalation of violence in the unfolding terror that would consume them. In this sense, therefore, the leadership of the Bolshevik party committed suicide. It was a grim irony that first secretaries were thus deploying unprecedented powers of life and death over their subjects at the very moment their own fates were being decided in Moscow.

The terror of 1937 destroyed countless lives of victims and their families. Many of those victimized wrote letters to people in positions of authority asking them to intercede on their behalf to correct injustices or otherwise alleviate their situations. Such letters were in a long Russian peasant tradition of appealing to powerful persons for help. Sometimes they were addressed to official bodies, particularly to the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of Soviets. More often, they were directed to particular persons: to Stalin or to M. I. Kalinin (chairman of the Presidium of the CEC and titular head of state). As the only one in the top leadership of peasant origins, Kalinin was nicknamed the “All-Union village elder” and as such received a huge number of letters of appeal. As far as we can tell, the vast majority of these letters went unanswered during the 1937–38 terror.

Part of the human tragedy of this terror was its effect on families. Not only did fathers and mothers who were branded as enemies disappear, but frequently (as in the case of Alexander Tivel that began this book) the relatives of those repressed were themselves arrested. We know, for example, that Stalin, Molotov, and the other Politburo members routinely approved lists of wives and/or children of “enemies of the people” who were to be arrested. As a person from the Caucasus, where traditions of vendetta and family vengeance were culturally rooted, Stalin perhaps naturally thought in terms of punishing kin groups as much as individuals. At a dinner on the anniversary of the October Revolution in 1937, Stalin mentioned this in a lengthy toast that was transcribed by Georgi Dimitrov:

Whoever attempts to destroy that unity of the socialist state, whoever seeks the separation of any of its parts or nationalities—that man is an enemy, a sworn enemy of the state and of the peoples of the USSR. And we will destroy each and every such enemy, even if he was an old Bolshevik; we will destroy all his kin, his family. We will mercilessly destroy anyone who, by his deeds or his thoughts—yes, his thoughts—threatens the unity of the socialist state. To the complete destruction of all enemies, themselves and their kin!89

On the other hand, possible retribution against family members also had more calculating political utility. The threat of retribution against one’s relatives would have a discouraging effect on possible traitors. In this atmosphere, promises that one’s family would not be repressed may also have encouraged those under arrest to provide the required confessions. Finally, as Molotov noted, it was necessary to remove arrested persons’ family members from society to avoid the spread of negative political sentiments. Indeed, when asked by Feliks Chuev in 1986, “Why did repression fall on wives, children?” Molotov at first did not even seem to understand why there was a question about it: “What does it mean, ‘why?’ They had to be isolated to some degree. Otherwise, they would have spread all kinds of complaints … and degeneration [razlozhenia: corruption, infection] to a certain degree. Factually, yes [they were re-pressed].”90 Once again, innocent people were victimized because of what they might do.

We will probably never know all the reasons for the eruption of wild terror in the middle of 1937. Nomenklatura fear of opposition, Stalin’s personal vengeance and fear of alternative leaders, the top leadership’s mistrust of those around them, and preparations for war all played a part.

By the middle of 1937, coinciding with Stalin’s coup against the “military plot,” suspicions hardened, political transcripts changed again, and the careful texts separating this and that group into enemies, comrades, and those making mistakes blurred together. There were now two distinct representations of reality. For the public, the enemy could be a party leader who had been a German-Japanese spy and assassin for years— even as far back as Lenin’s time—betraying socialism and carrying out secret conspiracies against the party. This construction of reality was the one found in the press and in the proceedings of the show trials. It masked personal and policy conflicts within the elite and attempted to rally the population by giving it negative examples and stark, simple depictions of common enemies. As Stalin explained to Dimitrov in a particularly revealing moment, it was necessary to blacken the reputations of those repressed as much as possible for the consumption of “workers [who] think that everything is happening because of some quarrel between me and Tr[otsky], because of St[alin]’s bad character. It must be pointed out that these people fought against Lenin, against the party during Lenin’s lifetime.”91 From the minutes of closed Central Committee meetings that we have seen, it is also more than likely that many members of the nomenklatura believed in the guilt of those arrested, although perhaps not in the accusation that they had been foreign spies for twenty years.

The construction of reality in the innermost circle was a bit different. Here, in the Politburo, it was a matter of personal trust and loyalty. The level of fear and paranoia among Stalinist leaders had reached such proportions that it led them to strike even against longtime friends and comrades, people who had supported the Stalin line without fail for years, if there was the slightest reason to believe that they had been or would in the future be disloyal. Possible future reality became present danger. Suspicion became guilt. Based on what someone might do in the future, he became the same as a spy today. A party leader could be arrested for having uttered “a liberal phrase somewhere.”92 For this insider’s view of reality, we once again rely on the unrepentant Molotov of the 1970s and 1980s, in this case remembering the interrogation of Yan Rudzutak:

MOLOTOV: Rudzutak—he never confessed! He was shot. Member of the Politburo. I think that consciously he was not a participant [in a conspiracy] but he was liberal with that fraternity [of conspirators] and thought that everything about it [the investigation] was a trifle. But it was impossible to excuse it. He did not understand the danger of it. Up to a certain time he was not a bad comrade….

He complained about the secret police, that they applied to him intolerable methods. But he never gave any confession.

“I don’t admit to anything that they write about me.” It was at the NKVD…. They worked him over pretty hard. Evidently they tortured him severely.

QUESTION: Couldn’t you intercede for him, if you knew him well?

MOLOTOV: It is impossible to do anything according to personal impressions. We had evidence.

QUESTION: If you believed it …

MOLOTOV: I was not 100% convinced. How could you be 100% convinced if they say that…. I was not that close to him…. He said “No, all this is wrong. I strongly deny it. They are tormenting me here. They are forcing me. I will not sign anything.”

QUESTION: And you reported this to Stalin?

MOLOTOV: We reported it. It was impossible to acquit him. Stalin said, “Do whatever you decide to do there.”

QUESTION: And he was shot?

MOLOTOV: He was shot.93

Molotov had a similar recollection about the Politburo member Vlas Chubar:

MOLOTOV: I was in Beria’s office, we were questioning Chubar…. He was with the rightists, we all knew it, we sensed it, was personally connected with Rykov…. Antipov testified against him….

QUESTION: You believed Antipov?

MOLOTOV: Not so much and not in everything, I already sensed that he could be lying…. Stalin could not rely on Chubar, none of us could.

QUESTION: Thus, it happened that Stalin did not pity anyone?

MOLOTOV: What does it mean, to pity? He received information and had to verify it.

QUESTION: People denounced each other …

MOLOTOV: If we did not understand that, we would have been idiots. We were not idiots. [But] we could not entrust these people with such work. At any moment they could turn….

There were mistakes here. But we could have had a great number more victims in time of war and even come to defeat if the leadership had trembled, if in it had been cracks and fissures, the appearance of disagreement. If the top leadership had broken in the 30s, we would be in a more difficult position, many times more difficult, than it turned out….

If we did not take stern measures, the devil knows, how these troubles would have ended up. Cadres, people in the state apparatus … such a leading composition—how it conducts itself, not firmly, staggering, doubting. Many very difficult questions which one had to solve, to take on oneself. In this I am confident. And we did not trust; that’s the thing.94

These events mark a drastic change in the pattern of Stalinist discourse. This period, that of “blind terror,” really marks the temporary eclipse of the discursive strategy altogether. It is as if the Stalinists, prisoners of their fears and iron discipline, had decided that they could not rule any longer by rhetorical means.

The texts on mass shootings were completely hidden transcripts; they were kept top secret and were not designed for circulation, discussion, or compliance in the party, state, or society. Unlike other party documents, they were not normative and did not prescribe forms of behavior. They were in no sense an implicit conversation designed to negotiate compliance. They involved no variant texts or emphases tailored to specific groups. Unlike with other discursive texts, there was no affirmation involved, either of unanimity or power relations. Nor were there suggestions of, or invitations to, established rituals or similar linguistic practices. Aside from those directly charged with the killings, no one was to know. In one sense, the outbreak of this blind terror was not the culmination of previous rhetoric; it was the end or negation of discourse altogether.