Chapter 3

How Did Jenny Tanner Die?

I started studying the Jenny Tanner case by approaching Denis Tanner for the inquest briefs and transcripts. I soon found that they told a story of dirty tactics, tunnel vision, incompetence and glaring mistakes that I wouldn’t have tolerated from a rookie constable. But they did yield a previously unpublished discovery: over the ten days immediately following Jenny Tanner’s death, police had tape-recorded almost all the conversations they had with each other, with witnesses and with her family and friends.

Denis Tanner and his counsel had been refused access to these tapes during the second inquest, but because the Coroner had accused him of murder, he was obviously entitled to them now. Police command said ‘no’, so I suggested that Tanner get a copy through the Coroner’s office.

The Coroner didn’t have them; his office said the police did. The police initially told the Coroner’s registrar that they couldn’t find some of them, but that defied belief; this was supposed to be a murder case, and you don’t lose murder exhibits. So Tanner and I went to see the Ombudsman, Dr Barry Perry.

I explained to Dr Perry that I thought Denis Tanner needed some help; Dr Perry agreed. I said that I might help him myself for a couple of months; Dr Perry encouraged me.

But Dr Perry struck the same hurdle getting the tapes. Only one came to hand, though it was a critical one: a conversation with police where Denis had explained what he was doing on the day of Jenny’s death. The tape proved that his explanation had been misrepresented in the media and at the second inquest: he had never given a conflicting alibi saying he was at the trots.

After the Ombudsman heard the tape and realised its importance, his staff kept pushing the police to release the others. An investigator told me he’d once turned up at the homicide office at 6 am, before the staff arrived.

In dribs and drabs, the tapes came to light. It would be two years before Denis Tanner was given all of them, ten in total. One disk came with a note from the Coroner’s registrar saying that Inspector Newman had described it as inaudible. Some parts were faint and couldn’t be deciphered, but the police had also taken notes. With my own audio equipment, I soon transcribed all of the tapes.

These tapes exposed the flawed approach taken by the Kale Taskforce. Only three of the ten tapes were transcribed for the Coroner or mentioned in his finding at the second inquest, though many of these recorded conversations had been the subject of dispute. The taskforce had taken statements from people about events that had occurred more than twelve years earlier without playing the tapes to assist the witnesses’ memories. Well-intentioned people and grieving relatives had sometimes embellished their stories, but their memories would have been improved if they’d been able to hear their tapes.

•••

There are two principal issues to resolve in every death investigation: the first is the cause of death, which in this case was two .22 rifle gunshot wounds to the head; the second is the manner of death – how the wounds were inflicted.

In my era all detectives were trained to interpret and reconcile physical evidence. We actually visited the scene of every crime reported. Police resources have always dictated that specialist forensic technicians are only called when the crime is substantive or evidence unclear. I’d have visited and analysed tens of thousands of crime and accident scenes during my 30 years of service.

The inquest evidence aroused the detective in me. It became obvious that the second inquest had given scant regard to the manner of death. The Coroner’s finding devoted only nine lines to discussing the evidence at the scene and made no attempt to reconcile the physical evidence with the differing hypotheses of suicide or murder. When I later compiled a document reconciling and reconstructing the scene from the physical evidence, it ran to 74 pages.

Crime scene investigator Daryl W. Clemens offers a useful outline of how an event should be reconstructed. He writes that investigators should draw together all the possible information from physical evidence, witness statements and the reports of other experts if they’re available. The range of physical evidence may include scene and autopsy photographs, measurements, drawings, notes, reports and items of evidence.

This information should be evaluated, for example by comparing witness statements to the physical evidence. The next stage is to formulate a hypothesis about how the event (or parts of it) occurred. Then follows the testing stage, which involves devising methods to validate the hypothesis, for example by checking the evidence against physical laws or attempting to replicate the event. The final stage is reconstruction, the reporting of the results of the analysis, with a probability range assigned to the various ways in which the event (or parts of it) may have occurred.

In this case, the police, the doctor and the ambulance officer made 32 separate and unchallenged observations of physical evidence, and the rifle was later examined by a ballistics expert. Each of those 32 points is consistent with suicide (see Appendix A). None supports a murder hypothesis.

Photographs would have been helpful in this case, but in 1984 police weren’t obliged to take photographs of obvious suicides. Police Standing Order No. 10.5 (b) stated: ‘In suicides, photographs are usually not necessary, but in exceptional cases they should be obtained, in which case the photographs should show the deceased in the position as found.’ In fact, it’s quite common for investigations to proceed without photographs, even in cases of murder. When police arrive on the scene of a violent crime, the first consideration is always for the victim. If there’s a chance of saving a life, you can’t wait hours for a photographer to turn up. This is especially so in the bush. In Jenny Tanner’s case, the police had no backup available, their police station was unmanned, they had nobody to call on their radio and it would take an hour to go to the station and back to get a camera.

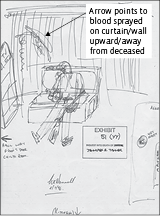

The police had drawn sketches of the scene recording the position of the body, the rifle, blood, the couch and a spent shell (Image 2); later, the ambulance driver also drew a sketch (see Image 3). Between them, the story was told.

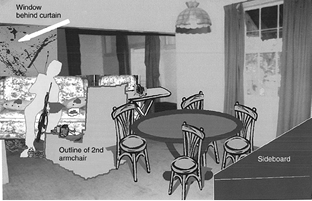

It was simple for me to reconstruct this scene because Laurie Tanner still had his furniture and a later owner of Springfield, Max Harvey, had taken photographs of every room in the house a few weeks before it burnt down in 1995. I collated the observations of each witness and built a computer image of the scene using one of Harvey’s photographs (see Image 4). This was bread-and-butter stuff for a detective, but nobody had done it in three separate police investigations spanning more than twenty years.

My reconstruction incorporates all the witness observations and is significantly different from the police artist’s sketch created for the second inquest (see Image 5). Several crucial details were omitted from that sketch: the baby’s bottle and two clean nappies in front of Jenny; the bloodstained towel with powder-burn marks; the blood spatters on the back of the couch, and spatters of blood and human tissue sprayed upwards on the curtains behind the body. The window behind the couch also wasn’t shown.

The sketch was inconsistent with observers’ reports in other areas, beginning with the couch itself. It was drawn as a pink three-seater covered with a sheet, but it was actually a floral two-seater with no sheet cover. The cushion on Jenny’s left in the sketch also should have shown an indentation and a large pile of congealed blood.

Two errors in the sketch are especially noteworthy: the biscuits are shown as being on a plate at some distance from Jenny, though Dr Gilham said they were close to her and in a barrel; and the cigarette was shown as being a distance from her body and facing away from her. There were no witness observations regarding the direction the cigarette was facing, but Jenny was a heavy smoker and always used this ashtray. If another smoker was in the room, it is logical that there would have been a second ashtray on a separate table near the chair where the other person was sitting. It should be noted that Denis Tanner was not a smoker.

•••

Contrary to the impression you’d get from the movies, there have been many multiple-headshot suicides, particularly when the weapon is a low-velocity .22 rifle, which is designed to kill birds and small vermin. People shot in the head with these rifles have been known to recover completely; there are cases where they’ve driven to hospital, made a cup of coffee or rung for help after being shot. It depends on whether there’s been damage to vital parts of the brain. A widely publicised example was that of the Australian twins who tried to commit suicide in 2010 by shooting themselves in the head with .22 target pistols at a Colorado shooting range. One young woman died instantly, but the other survived and was released from hospital five days later.

Multi-shot suicides can occur when an intending suicide test-fires the weapon or accidentally discharges it. After a first non-fatal headshot, the victim is groggy and may have lost vision or hearing. Sometimes victims lose consciousness for a while, then revive and try again. If you want to check for yourself, simply Google ‘multiple gunshot suicide’ and study the published cases.

A wealth of research has been published on multi-gunshot suicides. Professor Derrick Pounder, who heads the Department of Forensic Medicine at the University of Dundee, describes suicide by multiple gunshot as ‘uncommon but not rare’. He also observes that a contact wound ‘creates a presumption of suicide’, and that a suicide victim ‘may test fire the weapon before inflicting the fatal shot’.

Similarly, Richard Page Hudson, an international expert on multi-gunshot suicide deaths, has published a study of 58 cases of multi-shot firearm suicides in North Carolina. Four of the victims had shot themselves three times, and there are cases where suicides have discharged even more bullets. Dr Page Hudson concluded:

Greater awareness of the entity of multi-shot firearm suicides may reduce a number of misdirected homicide investigations and diminish unwarranted public arousal…Mistaken pursuit of a multi-shot firearm suicide case as a homicide is needlessly expensive and may cause prosecution of an innocent perpetrator.

In Jenny Tanner’s case, pathologist Dr Peter Dyte, who conducted the autopsy, was the only expert who actually had the brain in his hands. He noted that the first of the two headshots had passed through the frontal lobes, where there are no vital centres, and ‘bruised the undersurface of the brain’. His opinion was that Jenny could still have had the capacity to fire twice.

•••

The two shots to Jenny Tanner’s skull were both skin contact wounds, very close together, one above the other in the centre of her forehead. The head photographs show powder burning to the skin around the entry holes. All published papers, books and experts agree that a contact head wound is a sign consistent with suicide. American experts Michael J. Shkrum and David Ramsay quote a series of studies in which the proportion of suicides involving contact wounds ranged from 97 to 100 per cent; for homicides, the proportions were consistently less than 10 per cent.

In murders, shots are rarely fired hard against the skin, because the shooter can’t get that close; the victim is instinctively evasive and moves about. As a result, the wounds are generally all over the place – in the chest, the head, the arms and the back – and shots often miss the target completely. In suicides, by contrast, the shooter is always still. Two contact wounds close together almost always indicate suicide.

For a murder scenario to apply in Jenny Tanner’s case, the shooter would have to be standing in front of the couch, firing horizontally. At the second inquest, the Coroner found that the first headshot had been instantly fatal or incapacitating, accepting an opinion from neurologist Professor Andrew Kaye. But the known physical evidence doesn’t reconcile with this. It is significant that Professor Kaye had only examined a reconstructed fibreglass model of the skull created after it was exhumed in 1997. He was never advised of the physical scene evidence, nor was he asked to reconcile his opinion with that physical evidence.

In Professor Kaye’s murder scenario, Jenny Tanner’s head would have fallen forward onto her chest after the first, instantly fatal headshot. (Tests conducted by a French team using a biomechanical model have shown that the head doesn’t fall backwards in .22 shootings.) The murderer would then have had to fire vertically upward to inflict a second headshot at the same angle of penetration. It should also be considered that if Jenny had died instantly from the first headshot, there’d be no need for a murderer to fire again.

Jenny also had a through-and-through (exit) wound to each hand through the webbings between the thumb and forefinger. This is consistent with using her toe to fire vertically while her hands were cupped over the muzzle. The wounds didn’t go through the centre of her hands, as some journalists and authors would have us believe.

In Professor Kaye’s scenario, if the headshot had been instantly fatal, Jenny wouldn’t have had the capacity to sense danger to later raise her hands. In any murder scenario, the hand wounds could only have occurred before either headshot, when she had full capacity to resist and evade an attacker. But there was no evasion. Both head wounds were precise contact wounds in almost the same spot, and the room was undisturbed. The police who attended described it as ‘neat and tidy’ and looking ‘lived in’; even her cigarette had burnt its full length in the ashtray without disturbing the ash, the iron was still upright on the ironing board, and a part-filled baby’s bottle was standing beside a pile of fresh nappies stacked in front of her feet.

The hand wound evidence certainly does not support a murder hypothesis because the bullets or bullets that caused the hand wounds exited – they passed through the webbing between the thumbs and forefingers. If these were defensive wounds in the murder scenario where the weapon was discharged horizontally, the exited bullet or bullets would either have hit Jenny in the body or bypassed the body and shattered the window behind her. Neither of these things happened. A murder scenario where the hands weren’t raised defensively is also unsustainable. If her hands were in her lap, the bullet or bullets would have passed through the hands into her groin, stomach or leg; again, that didn’t happen.

The image used on the cover of Robin Bowles’ Blind Justice shows a woman holding her hands defensively in front of her face. This image has influenced many people, but it also demonstrates my argument. When the bullets pass through the hands, they must go somewhere (see Image 6). They might hit the body or head, or if they missed, they’d likely have hit the window behind her. But again that didn’t happen. Think about this image. If the bullets didn’t hit the body or shatter the window, where did they go?

When the headshots were fired, the rifle was pressed hard against Jenny Tanner’s forehead, so her hands couldn’t have been between the muzzle and her forehead. This means that at least one more shot had been fired to cause the hand wounds. Therefore a total of three or perhaps four bullets and their spent casings had to be accounted for. Two bullets were inside the skull; one spent casing was still in the breech of the rifle and another was on the floor against the couch. But what happened to the other bullets and spent casings?

The answer can be found in the police statement and inquest evidence of the ambulance driver Gerry O’Donnell. His sketch of the scene (see Image 3) showed blood and brain or bone spatter ‘sprayed upwards away from the body onto the curtains or wall behind the body’.

In his evidence to the first inquest, O’Donnell said:

Looking at Jenny on the couch I saw blood and some brain tissue on the curtains or wall behind her. This was certainly visible at the time and it was to the left – which is my left as I was facing Jenny and the wall or curtain. The blood and brain tissue was behind Jenny but sprayed upwards to my left.

Asked at the second inquest if it was possible that the tissue came from Jenny’s hands, he replied:

That would be possible. It was a different colour to the blood, the clotted blood that was there. It was a lighter colour and at the time, I assumed it was brain tissue.

He also recalled that the police had discussed this blood spatter path with him and had surmised that it was caused when she accidentally discharged the rifle with her toe while she was dazed. He said:

There wasn’t any question at that point that it was anything other than suicide, and at that point they said: ‘Well, she may have been holding the rifle and trying to get her toe into the trigger when it discharged.’

Only exit wounds leave blood spatters, and the spray pattern always follows the path of the exited projectile – in this case upward and away from the body towards the ceiling. The blood spatter couldn’t have come from either headshot because neither projectile exited, so the lighter-coloured tissue O’Donnell observed must have been fragments from the hand wounds.

This shows that the bullet or bullets that caused the hand wounds had been fired almost vertically, certainly at such an upward angle as to miss the window behind her. The police didn’t search, but at least one bullet would have lodged in the ceiling or the top of the window sash, remaining there until the house burnt down eleven years later.

Ballistic tests on the rifle also support vertical discharge. Adrian Barry, who examined the rifle for the 1985 inquest, testified that the last shot fired from the rifle was discharged within 15 degrees of vertical. Every pathology expert agreed the last shot was the higher and definitely fatal headshot.

At the second inquest, ballistics expert Ray Vincent said that a ballistic test taken on its own might be questionable because the rifle could have been roughly handled during the ten months it spent in the Mansfield police store. But the accuracy of Barry’s ballistic test is verified by O’Donnell’s evidence and his sketch of the spatter pattern behind the body. The evidence is inescapable that at least two shots were fired upwards at an angle close to vertical: a hand-wound shot (or shots) and the last headshot. Logically, the hand wounds can be explained as accidental, as the police at the scene originally surmised, and were likely to have occurred when Jenny was dazed after the first headshot and trying to reset her toe into the trigger guard.

It would be impossible for another person to have fired at that angle and inflicted those wounds. A murderer would have to lie on the floor on his back, between Jenny’s legs, firing vertically upwards.

We know that this didn’t happen for a number of reasons. First, in a murder scenario, the hand wounds had to have occurred before either headshot, so Jenny would have been fully conscious when the murderer was lying on his back between her legs. Secondly, the baby’s bottle and the pile of fresh nappies on the floor directly in front of her feet weren’t upset. The ash on her cigarette was intact, though it would have crumbled at the slightest disturbance. As Bill Kerr told Jenny’s parents and repeated many times in his taped conversations, there was no sign of any struggle.

The subjectivity of the Kale Taskforce investigation was evident when they constructed a video re-enactment for the second inquest, using a policewoman as a model (see Image 7). They made much of how difficult it would have been for Jenny to discharge the rifle at fifteen degrees from the vertical, but they didn’t construct the same test for how a murderer could have fired at this angle. In any objective analysis, the police and the Coroner should also have considered this question.

•••

Another simple but vital clue missed in this case was the location of the spent shells. The position where spent .22 shells are found generally determines the position of the shooter. In this case, there should have been at least three (maybe four) spent shells.

I have conducted tests with an identical rifle (see Image 8). With this rifle, spent shells are ejected back towards the shooter and to the right. If a murderer, who had to be standing in front of Jenny and facing her, had been firing and ejecting spent shells, the spent shells would have landed six to ten feet in front of the body, to the shooter’s right and to Jenny’s left. But no spent shells were found in front of the body.

If Jenny ejected them herself while seated on the couch, they’d eject towards her; they’d land on the couch beside her or on her lap, or fall on the floor against the front of the couch near her feet, which is exactly where one spent shell was found, behind her left heel and under the butt of the rifle. This spent shell is shown in Senior Constable Kerr’s in situ sketch (see Image 2). Another spent shell, the one from the last and definitely fatal headshot, fired vertically, was still in the breech.

Because the police initially thought there was only one headshot fired upwards through her mouth and that the wound on the forehead was an exit wound, they didn’t search for other shells. In the suicide scenario where Jenny was the shooter herself, a shell or shells would have been somewhere on the couch or perhaps between the cushions.

If a murderer removed spent shells from the house, as Operation Trencher detectives suggested to me as a possibility, that murderer was certainly not setting up the scene to make it look like a suicide, because when the police came they’d find only two spent shells for the three or four bullets that had been fired.

•••

The blood on the rifle also told a story. Both police and the ballistics expert testified that it was heavily covered with blood in four specific places, one with a palm print; all are consistent with Jenny being the shooter (see Appendix B).

Position one was on the stock around the trigger guard, on the front of the trigger guard and the front of the trigger face. Position two was on the front end of the stock, where there was also a palm print. Both are the normal positions where a shooter would handle a rifle while loading, firing or ejecting bullets.

The third position was on and inside the sight at the end of the rifle and in the bore and muzzle, consistent with holding the rifle at the barrel end in cupped hands; this is consistent with either suicide or murder. The presence of blood and brain tissue inside the bore again proves skin contact discharge, because in contact wounds the discharge causes a vacuum effect, sucking material back into the bore.

The fourth position was a blood drop on the lens of the telescopic sight, which can only have dripped from directly above the rifle. This is consistent with blood dripping from the hands holding the upright muzzle (as would occur in Image 10).

There’s no other explanation of the blood distribution on the rifle than that the shooter’s hands were bleeding while holding the rifle in a normal firing/ejecting position. If a murderer had been bleeding heavily from the hands, there’d be blood on the floor in front of the body, on the carpets and furniture. Forensic tests would quickly find and identify it. Denis Tanner turned up at Mansfield police station the next day, and he didn’t have hand wounds.

Senior Constable Bill Kerr’s sketch (see Image 2) also shows a rolled-up towel beside the body covered in blood. He described the towel as having two ‘holes with powder burns on it’. Those powder burns on the towel didn’t come from either headshot, because those were contact wounds; they must have come from the hand shot or shots, suggesting that Jenny may have been holding the towel when the rifle accidentally discharged. This also explains why one of her hands had minimal powder burning, and is consistent with her handling the towel to wipe blood from her face or hands while dazed from the first headshot.

This physical evidence is unassailable, as is my reconciliation of it. There is no evidence whatever that would support a murder hypothesis. When the Mansfield policemen assessed Jenny Tanner’s death as a simple suicide in 1984, they were right. Cynics may never accept this, but Jenny Tanner’s death was not murder.

2 Senior Constable Bill Kerr’s scene sketch (obtained under FOI)

3 Ambulance driver Gerry O’Donnell’s scene sketch (obtained under FOI)

4 Author’s reconstruction of death scene

5 Police artist’s sketch for second inquest (obtained under FOI)

6 Hands in defensive position (image courtesy iStockphoto)

7 Still from police re-enactment video (obtained under FOI)

8 Rifle showing direction of ejection of spent shells (image courtesy iStockphoto)

9 Shooter's hands in normal position for using rifle (image courtesy istockphoto)

10 Re-enactment by author and model (Newspix/Craig Borrow)