Chapter 4

A Marriage of Opposites

Jennifer Blake was born and bred in Mansfield, the eldest of four sisters. She attended the local convent school, then went to Mansfield High. Her father, Les, was a mill worker and her mother, Kath, worked in a local laundry; they raised their family in a mill house in Ultimo Street.

Jenny left school at sixteen and moved to Melbourne, where she worked as a hairdresser and lived with her grandmother in Mulgrave. When a teller’s job came up in the Mansfield branch of the State Bank of Victoria, she took it. Later, a compulsory transfer took her back to Melbourne for several years.

Jenny liked company; she was a fun person, attractive and popular. She was also forthright and strong-willed. She had a short fuse and was never frightened to speak her mind.

She met Laurie Tanner in 1980, when he was recently divorced from his first wife. He was a shy type, so Jenny asked a friend to tell him that she’d like to go out with him.

Laurie, the eldest of the Tanner children, was twelve years older than Jenny, and a taciturn, almost timid man. He’d left school at the end of third form after contracting meningitis, which affected his memory and concentration. His siblings pursued professional careers, but he was the son who stayed at home on the family farm. He was certainly not a party person; he preferred a cup of tea or a soft drink to a glass of wine or beer. Outsiders saw him as an honest, sober, hard-working farmer, ready to lend a hand to anybody who needed help.

Springfield was rugged country, and at 350 acres (140 hectares) was never big enough to be self-supporting. To make ends meet, Laurie worked as a shearer with local contractor Roy Friday and managed stock and property for absent landowners. In his spare time, he went to meetings of Apex, Young Farmers and the show society, did hospital and charity work and thrived on working bees. More than twenty years on, he hasn’t changed: he’s still active in the local show society and in Rotary, where he’s a Paul Harris fellow; he’s also immensely proud of the blue ribbons and trophies his fleeces have won at the Royal Melbourne and country shows.

Romance wouldn’t be one of his strengths. His first wife, Susanne, had been a trainee schoolteacher when they married. They bought Springfield from his parents and moved there on New Year’s Day 1977, but Susanne left after less than a year on the farm.

Their divorce settlement was simple. As there weren’t any children, their solicitors agreed that Susanne should receive a third of the assets; Laurie received two-thirds because he’d brought the proceeds of selling a house and another farm into the marriage, whereas Susanne had made no financial contribution. The mortgages remained in Laurie’s name. Knowing that Laurie hadn’t had time to establish himself financially, Denis, who was single and earning good wages as a policeman with no commitments, offered to ease the pressure by taking a loan to pay out Susanne’s share. Susanne received $20,000 in cash, which was enough for her to finance a small terrace house in Carlton. Later, when Laurie married Jenny, he and Denis didn’t want to be involved in a three-way partnership, so Laurie bought Denis out.

At the second inquest a mystery was created about where the money came from. The police said they couldn’t trace it, and the media claimed that the police suspected Denis had got it from running prostitutes. Nobody asked Denis, who had simply taken a personal loan from the Bank of New South Wales, which held the mortgage on Springfield. The bank later became part of Westpac, so it no longer existed under its old name when the police investigated in 1996. This was unremarkable detective work on an issue that could have been resolved by simply asking Denis.

•••

It’s hard to place Laurie and Jenny as a couple. During her years in the city especially, Jenny had experienced a lifestyle totally different from Laurie’s life on the farm. He reluctantly told me about an incident when he first met Jenny while she was sharing a flat in Melbourne with her sister Miriam.

He said, ‘I turned up there one day and they were having this incredible fight. They were pelting each other with crystal vases and glasses. There was glass everywhere…I was just amazed. They had been smoking dope and I didn’t know anything about that sort of thing. There was this plastic bag on the table that looked like it was full of lucerne chaff, but they said it was dope. Once she got serious with me, I don’t think that ever happened again.’

But opposites can attract one another. Laurie was flattered by the attention of an attractive, urbane younger woman who brought a new sophistication into his life. For her part, Jenny may have seen Laurie as offering the prospect of financial security; Springfield, although small for a sheep farm, was a step up from the mill house of her childhood. He was a genuinely nice man with no baggage who offered emotional stability as well.

When Jenny met Laurie, she was involved in a relationship with a married policeman considerably older than herself. He’d moved to Mansfield with his wife and family, but soon after their arrival his wife became ill with lymphatic cancer. The husband stayed on in Mansfield with his two children, but his wife went to live with her parents in Gippsland and died fourteen months later. Two months after his wife moved, he got involved with Jenny, who became pregnant to him. She had an abortion, one of four that she later disclosed to Laurie.

Not long after they started seeing each other, Laurie and Jenny became engaged. Jenny stayed with the State Bank, transferring from Melbourne to Yea, and moved into Springfield. Later, she found a job closer to home as bookkeeper at Yencken and Dyson, a Mansfield hardware firm. The couple married on 1 March 1981 at her parents’ home at Piries on the Jamieson Road.

After the excitement of the wedding and honeymoon passed, Jenny struggled to cope with the reality of farm life. Having always lived in town, surrounded by people and with shops just down the street, she couldn’t have anticipated what was involved in the change. Many say that to enjoy farm life you have to be born to it.

In 1982 Bonnie Doon still had poor television reception, and there wasn’t much choice of radio. Jenny’s telephone was her principal entertainment and means of contact with friends and family. Springfield was two kilometres from Bonnie Doon, almost thirty kilometres from Mansfield and forty kilometres from her parents. The farmhouse was old and surrounded by mighty cypress trees that blocked the wind, the passing traffic – and the sunlight. Her closest neighbours were elderly, so she had little in common with the womenfolk around her. Her husband, who’d lived on this farm all his life, was set in his ways.

With Laurie away shearing and contracting during the day, Jenny was lonely. Her main company was her husband’s ageing father, Fred, who came almost daily to do the homestead chores. Before she and Laurie married, Jenny had declared that she’d do the books and keep the records, but she wouldn’t do the farm work.

At night Laurie went to meetings as he’d always done, leaving her home alone. The stillness of the night was broken only by the noise from the pack of farm dogs chained under the cypresses. They barked constantly, becoming frenzied if headlights flashed through the trees or a car stopped on the road.

Police statements by Jenny’s friends and family are full of stories about her hating farm life, especially the dogs, as are the notes Bill Kerr took when he interviewed her friends and family after her death. Jenny’s mother told Kerr:

Laurie said she didn’t like the farm life – now, Jennifer can’t be bothered with animals…our other kids trip over themselves for the dogs and the cats and that, but Jennifer doesn’t, you know – she’d just as soon kick them out of her way.

Some friends reported that Jenny had complained that when Laurie’s family visited what was now her home, they treated it with too much familiarity. Springfield had always been their home and old habits are hard to break, so perhaps they were unwittingly intrusive.

Jenny compensated for her new solitude by doing the place up: refurbishing, painting, buying carpets and furniture, knocking a wall out. Her father was a competent and willing helper in these projects. She was also engrossed in shopping: Kerr’s tapes of his conversations with her parents and close friends are littered with anecdotes about Jenny purchasing furniture, going to clearing sales, or buying presents that her mother thought were shockingly expensive. Melbourne trips became her way of life. She wouldn’t just go there and back in a day; she’d regularly stay with Denis and Lynne Tanner at Spotswood for days at a time, sometimes once or twice a month, shopping and having her hair done.

Jenny fell pregnant in June 1982. Perhaps she thought that a child would overcome her loneliness. She chose Dr Patience from Benalla as her obstetrician because her Mansfield doctor didn’t have obstetric rights at Mansfield Hospital. Dr Patience made these observations to both inquests:

I saw her on ten occasions during the pregnancy. Her demeanour during the pregnancy wasn’t the usual expectancy of most of my young prospective mothers, but I interpreted her taciturn nature as mere shyness.

Sam was born on 14 February 1983. A beautiful baby boy with fair curly locks, Sam became the love and purpose of Laurie Tanner’s life. Jenny, however, was struggling.

The birth wasn’t easy; after ten hours in labour, Jenny had a caesarean section. Afterwards, in the words of her friend Ros Smith, Jenny ‘was worried that lack of oxygen may have affected the child’. Jenny also told Laurie she was concerned that Sam might have suffered harm from her four previous abortions.

On 4 March and 31 March 1983, Jenny and Sam visited Dr Patience in Benalla, her last visits in respect of the birth. In his report to the first inquest, the doctor said Jenny had recovered well physically from the caesarean, but it was clear that ‘she was having no joy raising her infant son’.

Laurie told me that Jenny withdrew after Sam was born. To outsiders and family she presented a normal front, but privately Laurie could see an alarming change in her: she gained weight, stayed in bed late, and became ‘cranky’. As he puts it: ‘In company butter wouldn’t melt in her mouth, but when she was left on her own with myself and Sam, she would get these terrible fits of anger and mood swings. She would use “f” and “c” words that I can’t even bring myself to say, which was language that I had never heard her use before we were married. It was totally out of character.’

Laurie tells of another incident involving her sister Clare, who’d stayed overnight after looking after Sam with her mother while Jenny and Laurie went to a birthday party. Laurie says, ‘Next morning I had to go and get a bull ready for a bloke to pick up, and I was at the yards near the house when Jenny walked out the back door and gave me a real payout for having left her alone with Sam. It was a cold, frosty morning and I wondered who would hear it. The language was shocking, and Clare was so shocked she wouldn’t stay with us for a while after that.’

Jenny’s outbursts of anger upset Sam, who already cried a lot and had trouble settling because he suffered from earaches and gastric reflux. Laurie says, ‘Often at night I had to put him in the car and drive for hours to get him to sleep, and then soon as I got the car back in the shed, he would wake up and cry again.’

During the day Sam spent most of the time in his cot. If he needed changing, Jenny would clean him up and put him straight back in. Laurie says, ‘One of our friends, Angie McCormack, said to my mother once after Jennifer died, “I think Sam is going to have to learn to walk in his cot.”’ When Laurie was home, ‘all of the getting out of bed and looking after Sam was my job. She just refused. She would stay in bed until lunchtime unless she had visitors.’

Jenny’s mother, Kath Blake, told Senior Constable Bill Kerr much the same thing in their taped conversation a week after her death.

Jenny was lazy. We always said that. Jen – she’s lazy, you know. Probably you could probably go down there one day in the week and there’d be things – dishes and things like that…

I used to think, heavens, couldn’t you put that dirty nappy out at night?…We’d go to Melbourne sometimes…and that dirty nappy would probably sit there all day, to me I would have run and stuck that out.

This behaviour is consistent with Jenny’s being unhappy, even depressed.

When the shearing was on, Laurie not only had to labour in the sheds, pen and muster the sheep and class the wool, but he had to go to the house and make sandwiches and tea for his workers. Shearer Ron Tait and rouseabout Bob Fleming confirmed this in their police statements.

Jenny continued to make frequent visits to the city, where she’d developed a genuine sisterly friendship with Lynne Tanner. Easygoing Laurie was happy that Jenny maintained her freedom, and he sometimes accompanied her, staying with Denis and Lynne. Jenny also occasionally said she was going to visit her grandmother at Mulgrave, leaving the baby with Lynne, who had no children of her own. After Jenny’s death, Lynne wondered why Jenny didn’t take her baby with her to garner a great-grandmother’s attention.

These constant trips to Melbourne were unusual for a farm wife; most would only go shopping in the city as a treat once or twice a year. Most needed a local job to supplement the farm income, and to keep their towns alive they shopped locally. Only farmers and those raised on farms know the frugal lifestyle of farming. Where most people are paid every fortnight, a farmer receives nothing until the wool cheque arrives or the crop sells. But Jenny did do the bookkeeping and paid the bills. Laurie says that she was very good at this, but she would have learnt a lesson of thrift from a farmer’s perspective.

At Springfield, as the stay-at-home wife, Jenny became slave to answering the telephone and taking messages for the absent Laurie. In one of Constable Kerr’s tapes, her sister Clare related what it was like when she stayed at Springfield overnight to look after Sam while Jenny was away on one of her Melbourne visits:

[Laurie] came home, and…people just kept ringing up…I was in watching the television and he was on the phone the whole night and then I said I was going to bed and he said he’d go to bed too and then the phone rang again.

Jenny herself had little inclination towards the voluntary community service in which Laurie was consumed. June Tanner encouraged Jenny to go with her to the local bingo on Wednesday nights, and for a time Jenny kept the books for the organisers. But after her son was born, she went less frequently; the night she died was a bingo night, but she stayed at home.

She did join the local playgroup, which consisted of half a dozen local women with babies or small children. Jenny had been the playgroup host mother on the day she died. Sam at that stage was 21 months old and not yet walking. Most babies are walking by twelve to fourteen months: could comparing her child’s development with that of others in this competitive world of young mothers have brought her fears to a head?

Laurie knew Jenny was worried about the child. Kath Blake regularly expressed concern about his walking, and Jenny had sought several GP opinions and specialist paediatric advice, but was told that he was simply a late developer. For the second inquest into her death, only one of the doctors she consulted about Sam was interviewed. He was Dr Ross Gilham from Mansfield, but there was little he could tell the inquest about Jenny’s concern for Sam’s health, because police had seized his patient notes and kept them. During his examination at this inquest, the doctor was asked how often he’d seen Jenny about Sam in the six months before she died. He replied:

I can’t be certain of that. I’ve asked the police for my notes of that time. When I asked the police last year for my notes I was told that they were not available. Some four to six weeks ago I made enquiries myself and I was told that the notes were there and that the misunderstanding had been that people had been searching for notes on Jennifer Tanner and not on Samuel Tanner. I then asked the police if I could have copies of all my notes dealing with the Tanner family, but those that were transmitted to me by fax were only those relating to Laurie Tanner and not to Sam, therefore I cannot tell you exactly how many consultations I had in that time.

This line of questioning was dropped, and the notes weren’t retrieved from the police so that the doctor could consult them when giving evidence.

Dr Gilham did tell the inquest of Laurie’s concern about Jenny’s mood swings:

My recollection is that he was very concerned that it was something that he could not do anything about…the way it was conveyed to me was that there was a significant problem, which was causing him concern.

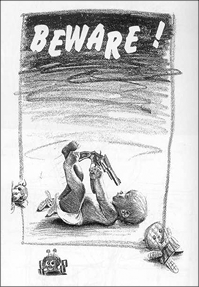

At some stage Jenny placed a poster of a baby holding a revolver to its head on the door of her refrigerator (see Image 11). This could be interpreted as warning of the dangers of having firearms near a baby, but it could equally indicate her negative attitude towards her child. Her mother noticed that police had removed the poster and told Senior Constable Bill Kerr:

Well, it’s been there for years and…it had been there because we never have guns…we are dead against them…I didn’t want something sinister read into that…that there was a threat or anything…I noticed it was gone when I went down there…I hoped that it wasn’t…that she put it there with some evil intent. It has to be a plus for Jennifer.

Kath Blake was mistaken in thinking that the poster had been there ‘for years’. It was published in Victoria Police Life in September 1983, a year before Jenny’s death. How she came to possess it is a mystery. Police Life was only distributed to police stations, so she must have obtained her copy from a police officer. It’s possible that she found it on one of her stays with Lynne and Denis, but she could also have obtained it from another police friend.

Laurie was so distressed by Jenny’s inability to cope with the child that he took a day off work to seek advice from Dr Patience in Benalla on 26 October 1983, shortly after the baby poster was published. Laurie doesn’t recall if that was why he went to the doctor, but both he and Dr Patience agree that he broke down uncontrollably during the consultation. Dr Patience told both inquests:

I was aware there were problems in regard to Jennifer, her mood, her handling of her infant son. Not openly admitted by her, but from my observations of her and her son when she came over on the two occasions post-natally and also on communication from her husband.

Jenny was also suffering from the effects of an old injury. On a high-country camping escapade when she was fourteen, she was knocked unconscious after she was thrown from a horse and dragged for some distance with her foot caught in the stirrup. The young people there didn’t get any medical help, Laurie says: ‘She just came to and she vomited during the night from the concussion.’

Her father told Bill Kerr about this:

Years ago she had a fall off a horse and she was pretty sick at the time, but she has always been affected down one side of her neck and into her shoulder. Now, she had X-rays and been to different people about it…I don’t know how many, but over the time it’s been quite a few, and Laurie said that sometimes it…nearly drives her over the wall…She couldn’t get her socks on.

After Jenny died, her parents asked Laurie to tell the police about the incident, so he told Bill Kerr. Though his call and Les Blake’s were both taped, neither was transcribed for the second inquest, and the Coroner’s finding ignored the issue.

Familiarity with the rifle

When Kath Blake insisted that she and Jenny both hated guns, the second Coroner’s finding took this claim at face value, but there is substantial evidence to the contrary. Police notes and taped interviews immediately after Jenny died include a consistent statement from Laurie Tanner: ‘I taught her to use the rifle when the escapees were around.’

On 15 March 1982, a year into their marriage, two Pentridge jail escapees tied up a council worker at the toilet block near the Bonnie Doon bridge across Lake Eildon, three kilometres from Springfield. I responded to the initial call and was one of the detectives involved in the search. It was several days before the escapees were recaptured, one near Benalla and the other in Melbourne. In the meantime the locals were on edge, with heavily armed police searching farms and homes. Springfield was one of those properties, and Laurie gave Jenny some basic instruction in operating their .22 rifle in case she needed to protect herself when he wasn’t at home.

Afterwards, Laurie and Jenny kept the rifle on the wardrobe in their bedroom and stored the magazine and ammunition in a kitchen cupboard. When Jenny drove around the farm with him, she’d occasionally shoot at a target he’d set up. He also claims that Jenny told him she’d sometimes fired a police weapon when she was going out with the Mansfield policeman. He’d occasionally take her with him on patrol, and she’d tried using a police revolver, which had nearly deafened her.

Laurie doesn’t like firearms and has always been uncomfortable killing. Even today he gets others to put down sick or injured stock. But sheep and cattle were his livelihood, and from time to time the rifle was a necessity. During lambing season particularly, he’d have the rifle in his utility to shoot predators that attacked the ewes and newborn lambs. During his marriage to Jenny, he doesn’t recall ever going shooting in the recreational sense, nor did any of his family members; the Tanners weren’t a family of hunters.

An incident at the beginning of April 1983 illustrated Jenny’s explosive temper and her capability in using the rifle. On Saturday 2 April, when Sam was just six weeks old, Laurie and Jenny had a dinner appointment at her parents’ home. True to form, Laurie arrived home late. Jenny was furious.

Next morning, Laurie found his prize breeding kelpie dead on its chain. He took the dead dog to a Mansfield veterinary surgeon, who conducted an autopsy and found that the dog had been shot in the heart by a .22 rifle bullet. Laurie reported the incident to the police, and Bill Kerr came out. A few weeks later Jenny apologised and confided that she’d shot the dog while he was in the shower before they went to dinner with her parents because she was furious with him for being late.

Laurie didn’t report this to police. In his eyes, it was nobody else’s business. Jenny was his wife, and he kept her secret because he knew that she was having trouble coping. It was one of the issues that caused him to seek counsel from Dr Patience in October that year. Bill Kerr’s notes show that Jenny’s neighbour Val Almond told him she thought that ‘Jenny may have shot the dog.’

On this issue, journalists have consistently misled the public by claiming that this dog was shot the day before Jenny died; the sinister implication is that Denis Tanner shot the dog so that it wouldn’t bark when he came to murder Jenny the next night. The vet’s diary and records confirm the autopsy date as being eighteen months before her death. It’s also worth noting that five other dogs were left alive to bark at any potential murderer.

Weeks after the dog was shot, Jenny and Laurie had another escapee scare. Four prisoners – three armed robbers and a murderer – escaped from Jika Jika, the maximum-security unit in Pentridge jail. Police intercepted them in a car on Wednesday 20 April, ten kilometres on the Melbourne side of Springfield, but the crooks ran off and scattered through the paddocks. I was there within half an hour; over the next four days, hundreds of police and media descended on Bonnie Doon. Laurie and Jenny kept the rifle loaded on their wardrobe, and they both made sure she was capable of using it.

Police recaptured two of the escapees on the first day and another the next evening, close to Springfield. The fourth remained at large until the following Saturday morning, when a dog squad officer and I captured him in a churchyard in Euroa. Enterprising local traders capitalised on the town’s growing notoriety by marketing T-shirts and tourist memorabilia with the slogan ‘Escape to Bonnie Doon’ – for locals, a light-hearted reminder that Bonnie Doon had twice been the centre of the current-affairs universe. Jenny sent some of this merchandise to her friends.

Depression and denial

Depression is often misinterpreted as a character fault or a sign of weakness, leading sufferers to hide the problem with disastrous results. Major depression is far more prevalent among women than men, and is especially common after childbirth. An Australian study has estimated that more than one in five mothers suffer depression. And, as Dr Marie-Paule Austin has observed, ‘Often the focus of a mother’s fears and depressive concerns is the well-being of her baby or her sense of inadequacy as a parent’. All these factors were pertinent in the case of Jenny Tanner.

Jenny herself was in denial about her depression, repeatedly telling her husband that there was no point seeking treatment because nobody could help her. This made things even more difficult for Laurie, who was out of his depth with Jenny’s mood swings and found it difficult to talk about them. But he did approach Dr Patience, and also spoke to her father. In his second inquest statement, Les Blake said:

As far as I know there were no problems within Jennifer and Laurie’s marriage, except for one occasion when Laurie mentioned to me that they were having some difficulties, the precise nature of which, I didn’t know. I didn’t ask them and I didn’t pursue the matter at all as I didn’t want to be seen as interfering. I thought that Laurie might have been over-anxious, because of the problems with his previous marriage. As far as I was concerned they appeared outwardly to be OK.

Others noticed that Jenny’s mood swings continued beyond the norm for post-natal depression. Dr Don Kemp was a Melbourne orthopaedic surgeon who owned property in the district. Laurie looked after it for him, so he had regular contact with Jenny. Dr Kemp noticed her ‘lack of lustre and not a great deal of spirit’, but he stresses that he didn’t assess her as a professional; he simply sensed she was suffering depression and felt that she needed help. In mid-1984 he told Laurie of his concerns, alerting him to the dangers of depression and suggesting she get treatment immediately. To help, he gave them use of his time-share holiday unit for a two-week break on the Gold Coast in July 1984.

Laurie takes up the story: ‘On the way up, we stayed overnight at a motel in Coonabarabran, and everything we lifted up had mice under it. Jenny freaked out and Sam wouldn’t settle down. I spent the night driving around with Sam in the car for a couple of hours while she had a sleep.’

But Jenny was fine in the holiday environment, visiting her friend Ros Smith and getting attention from Laurie, who was always there to look after Sam. During this time of respite, she tried to talk Laurie into selling the farm, moving to Queensland and getting a nine-to-five job. He rejected the idea; farming was his life and Mansfield was his home. On this trip, he also told her he’d like to have another child; he was hoping for a daughter.

Dr Kemp could tell that Jenny was still depressed when they returned to Mansfield. ‘I could see that it was there and she hadn’t changed all that much when she came back. I think they had a pretty miserable time to tell you the truth, because of the mouse plague.’ He spoke to me about women’s experience of depression after childbirth: ‘I’ve seen the post-natal depression last for months and then it can merge into ordinary depression due to the stress and strains of trying to bring up a baby and not getting any sleep, so where one stops and where the other starts, it’s pretty much irrelevant.’

On 30 July 1984, shortly after returning from Surfers, Jenny took her child to Dr Patience, who referred Sam to a paediatrician. Jenny also asked Dr Patience for a gynaecology report to see whether she’d require a caesarean if she had another child. Her mother confirmed this in her taped conversation with Bill Kerr, but it seems Kath was more concerned about Sam:

She had gone to Melbourne and [had] some X-rays done…I actually hadn’t said to her, ‘What did the doctor say – did he say yes, definitely a Caesar?’…We were really more interested in Sam at the doctors and I asked…‘What was Sam’s report with his walking?’ I didn’t say what did you do about…you know…your business.

The assessment was that Sam was a slow developer, but there was nothing significant wrong; the main issue was Jenny’s state of mind. Dr Patience later said, ‘I can recall…one of the letters back from one of the referral paediatricians commented that he had low muscle tone, he was a bit floppy.’ His comment indicates that Sam was referred to more than one paediatrician, yet not one of them was identified, interviewed or called at either inquest.

In September, Jenny started fainting for no apparent reason. This was mentioned on the tapes but wasn’t canvassed at her inquests. Her mother told Bill Kerr that on 5 September 1984, Jenny fainted at the bingo in the Bonnie Doon Hotel. She also fainted when Laurie was at home on several occasions, and she told him it had happened when he wasn’t around. She had severe headaches and believed she had a brain tumour. She told Laurie that she’d been to Dr Smith in Mansfield, another doctor not called to the second inquest or interviewed by police.

It was obvious that Jenny had had more extensive contact with doctors than the inquests revealed, so I asked Laurie to find her bank records and chequebooks, something the police hadn’t done. The cheque butts tell a story of multiple visits to previously unknown doctors.

Contrary to the evidence of Dr Patience, who told the inquests that her last visit to him was on 31 March 1983, her cheque butts show that she paid fees to Dr Patience on six occasions after this: in 1983 on 12 June, 10 August, 20 October and 17 November, and in 1984 on 16 May and 30 July. The last is the day she took the child for paediatric referral, and another may have been for Laurie’s visit to seek help on 26 October 1983; the other four dates are unexplained. Dr Patience wasn’t examined about her child’s consultations or patient notes. After the 30 July 1984 consultation, Dr Patience would have seen Jenny again to give her the result of her own and Sam’s tests, but the doctor’s evidence did not account for that visit.

She also paid a cheque to Dr Bristow, a Box Hill paediatrician, on 16 October 1984. If he is the one to whom Dr Patience referred Sam, then that cheque is dated four months after the referral. The date also coincides with the receptionist’s memory of Jenny’s visit to Dr Patience a month before her death. The receptionist remembers that Jenny and Sam had a later consultation. Perhaps another doctor referred Sam to Dr Bristow? No police inquiries were made about this, and Dr Bristow was never interviewed.

Jenny’s chequebook also shows several visits to Dr Gilham, which would be for Laurie and Sam. There were also other unexplained doctors in her chequebook: Bardsley (1 August 1983), Schultz (1 August 1983), Davey (7 February 1984), Alphins (2 August 1984) and Esser (4 October 1984). Her mother said she visited Dr Appleby after her fainting spells, but he doesn’t feature in the chequebook. The dates do match cheques to Taft, Dorevitch Pathology and Melbourne Radiology Centre; but which doctors referred her?

It is extraordinary that neither inquest sought out these doctors, who’d all have had information that was relevant to Jenny’s state of mind. In all, only two of the twelve doctors she consulted were called, which is certainly not a thorough investigation.

•••

Knowing that personal notebooks and diaries often tell a story, I asked Laurie for Jenny’s private birthday/address book. I was surprised to find that, despite Jenny’s apparent popularity, her book only listed the birthdays of three friends outside her immediate family: Lynne Tanner, Ros Smith and Lyn Timmins. Odd, I thought, for an outgoing, fun-loving girl.

At various stages, all three of Jenny’s close women friends seem to have become aware that something was amiss. Her sister-in-law Lynne Tanner noticed the change when Jenny stayed with them. Jenny would never get up to the baby at night or change a nappy, so Lynne did this when Laurie wasn’t there. In her professional life, Lynne was a policewoman dealing with women in crisis every day, and she became concerned when Jenny confided that she was having trouble coping with the child. Lynne approached two police surgeons, Dr Bush and Dr Jappe, for advice. She told Bill Kerr about this in a taped conversation a week after Jenny’s death, and repeated it in a much later taped conversation with her friend Helen Golding. Neither police doctor was called or even interviewed for the second inquest. These tapes also revealed Lynne’s affection for Jenny as ‘the sister I never had’. Statements by Jenny’s sisters confirm this close relationship.

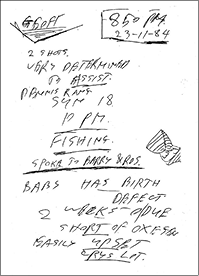

Jenny’s Queensland friend Ros Smith first featured in Bill Kerr’s notes eight days after Jenny’s death, when he spoke to her by phone. During that conversation, Smith denied that Jenny was worried about her son, but a message passed on the following day told a different story. Smith was related to the wife of Geoff Adams, a retired Mansfield policeman, and he relayed the following information to Kerr on 23 November 1984: ‘Spoke to Barry and Ros. Baby has birth defect – 2 weeks overdue – short of oxygen – easily upset – cries a lot.’ (See Image 12.) Kerr obviously mentioned this to Detective Sergeant Ian Welch, because in a report submitted in January 1985, Welch said: ‘The deceased may have believed the baby was retarded – source S/Const Kerr.’

Jenny’s Melbourne friend Lyn Timmins had been overseas, so they had no face-to-face contact from May 1984 until 26 October 1984. Timmins and Laurie shared the same birthday, 30 October, and often celebrated together. She stayed at Springfield from Friday 26 October to the next Sunday, when they toasted their birthdays before she returned to Melbourne.

Bill Kerr spoke to Timmins immediately after the death. In that conversation, Kerr quoted her as saying of Jenny: ‘She was proud of Sam, but didn’t go out of her way to show him off.’

Timmins didn’t make a formal statement until she visited Mansfield on 10 December 1984, and that statement, which was very brief, didn’t include the comment attributed to her earlier. It seems Jenny’s mother was keen to scotch speculation that her daughter might have suffered from depression. In a taped conversation on 21 November 1984, Kath Blake asked Kerr which of Jenny’s friends had told him that Jenny was depressed, and said she’d spoken to her ‘best friend’:

I was told that she said Jennifer was depressed. She rang me…yesterday…I waited till she said…that they had talked it over and I said, ‘You know about it?…Well. Did you say that you knew about it?’ and she said, ‘Never.’ But I was told definitely…that that girl had said she knew about it.

Timmins told author Robin Bowles that on the day she made her statement, she hid in a shop doorway to avoid Mrs Blake when she saw her in the main street.

Jenny’s next-door neighbour, Val Almond, appears to have told Kerr that things weren’t well, but he didn’t take a statement from her. Kerr’s handwritten notes, written on scraps of paper, list the names of Lyn Timmins and Val Almond against a variety of comments. The comments, some of them conflicting, were as follows: ‘Noticed difference in personality prior to baby and after birth’; ‘Didn’t show baby off like other women do’; ‘Very quiet and unassuming in that way’; ‘Didn’t have a lot to say about the baby’; ‘Didn’t carry the baby around everywhere like other women do’; ‘Didn’t show baby off’; ‘When people commented how good/beautiful baby was she would just stand there with a smile’; ‘Didn’t react to praise of baby like other women do’; ‘Lacked pride’; ‘Clean neat person’; ‘Looked after herself, Laurie and the baby well’; ‘Regularly said she hated the dogs barking’; ‘Not known if Jenny and Laurie were bluing just that Jenny hated the dogs and possibly shot their dog’; ‘No real angry emotion’. Although Kerr recorded these comments, he didn’t pursue the issues they raised when he was taking witness statements.

Another woman Jenny knew, Deborah Poole, only spoke publicly after Jenny’s death became a media issue in 1996. Poole had left Mansfield when she was nineteen years old and was at Ballina in northern New South Wales when the Kale Taskforce took her statement. She embraced the media fame the new investigation gave her, claiming in TV interviews and documentaries that Jenny was her best friend, though they’d mainly had telephone contact in the nine years since she’d lived in Mansfield. She claimed that she had stayed with Jenny twice at Springfield, but Laurie doesn’t recall this. Jenny didn’t speak to him about Poole, and I noted that she wasn’t mentioned in Jenny’s birthday and address book.

Poole wasn’t called at the second inquest. Many points she made in her police statement and media interviews simply repeated press misinformation. She claimed, ‘I knew about the two bullets at the funeral. The whole of Mansfield knew for goodness sake.’ The truth was that Kerr didn’t tell either family for ten months. Poole also claimed there was friction between the Tanners and the Blakes at the funeral because the Blakes no longer had access to Sam. This too was wrong. The Blakes took Sam immediately after Jenny died and looked after him until the Monday after the funeral. He spent every Sunday and special family occasion with them for the next twelve years. Poole’s comments allowed the media to portray the Blakes as victims.

There were obvious contradictions in Poole’s police statement She said she’d spoken to Jenny about three days before her death and found her ‘very happy and cheerful within herself’. But later in the same statement Poole gave a different story:

In one of our conversations she said she didn’t like living at her property in Bonnie Doon because she felt a bit isolated and she felt uncomfortable that Laurie’s first wife had also lived in the home. She also told me that she was having some marital problems with Laurie and mentioned she was left at home by herself a lot and was feeling lonely…this conversation took place during the phone call we had a few days prior to her death.

Speaking to Robin Bowles, Poole told a story that supported Laurie’s own experiences of Jenny’s moods. She recalled that Jenny used to call Sam ‘the little shit’ because he was sometimes naughty, and that one day she’d reacted angrily when he upended a bowl of sugar on the carpet while Jenny was on the phone to Poole.

A few weeks before her death, Jenny started planning to have Sam christened and asked Denis and Lynne Tanner to be the godparents. The christening issue caused conflict with her mother, who pressured her to have the ceremony at their church. As Laurie tells the story, Jenny defied her mother because she was still put out at the priest’s refusal to allow them a church wedding. ‘It was just Jenny’s decision – not mine, it wasn’t an issue to me, but it was with Jennifer; she was pig-headed like that…Because of the fuss that her mother was making, Jennifer decided on a private christening. It hadn’t taken place when she died.’

Although Kath Blake was keen to avoid any suggestion that Jenny had been depressed, she spoke of her daughter’s rages in a taped interview with Bill Kerr:

If things didn’t go her way, you know if the car…played up, the washing machine broke down, she would…go stark raving mad about it.

Laurie remembers many instances of Jenny’s anger close to the time of her death, though he couldn’t put dates to the outbursts. One day she yelled at him and Sam, ‘I hope you both get killed.’ On another occasion, when he was coming in for lunch, he heard her tell Sam, ‘Lift your game you little bastard or you’ll get the same as the kid on the fridge.’ Sam’s misdemeanour had simply been to open the doors on the stereo unit and pull some of the contents out; something he broke was only fixed after she died, so the incident must have occurred soon before.

Laurie also recalls Jenny flying into a rage when Sam bumped her cup of coffee and spilt it on the couch. ‘She went absolutely ballistic and screamed at him and dumped him in the corner over near the sideboard and wouldn’t let him out for ages. He was just bawling his eyes out with fear, and he was trying to crawl around the back of my chair to get to me, and she kept screaming at him. The look on his face was terrible, poor little bugger.’

Laurie once remarked to Jenny that he was likely to die before her because of his age, but she insisted that she was going to die first. ‘Don’t ever bury me in Mansfield,’ she warned. ‘I’ll come back and haunt you.’

Preparing for death

With hindsight, it could be interpreted that Jenny was thinking about her own death for some weeks beforehand. On 30 October, Laurie came home in the evening to find Jenny upset with Sam. Her temper so alarmed him that he decided to take the child with him when he went into Mansfield. Jenny followed them out and said to Sam: ‘Lift your game, you little bastard. One day you will come home and my fucking brains will be blown out.’

Former policeman Bob Fleming was Laurie’s friend and sometimes worked for him as a rouseabout. On Sunday 4 November 1984, ten days before Jenny died, he called at the house to get his pay. Jenny told him that Laurie had taken Sam to check stock in the back paddock and invited him in for a cup of tea. Mr Fleming noticed that Jenny was packing clothes to give away: ‘Jenny had clothing folded on the floor – some in open boxes…I said to her, “the spring cleaning?” Jenny said she wouldn’t be needing these and she told her sisters to come and go through it before she took what was left to the opp-shop…I thought she wouldn’t have many clothes left with the amount of clothes she was throwing out.’

Jenny’s father, Les Blake, commented in Andrew Rule’s SBS documentary that Jenny had left all of her photographs ‘beautifully mounted in albums, all dated with lovely text’. These photographs were of the happy times during Jenny’s marriage to Laurie, of their child and their friends. I suspect that Jenny may have prepared these albums for her husband and their son. They were stored in her sideboard at home, but her parents took possession of them when cleaning the house on the Monday after her death. It was several years before Laurie could bring himself to ask if he could have some of them back. He now has just two photographs and a few wedding snaps to remind him and Sam of their wife and mother.

Laurie still unashamedly declares his love for her. Until the police- and media-driven fracas broke out, he’d placed handpicked flowers on her grave without fail every Sunday morning when he took Sam to spend the day with Jenny’s parents. When the publicity arising from the new police investigation came into their lives in June 1996, the boy stopped these visits of his own volition.

Today Laurie still visits Jenny’s grave on Sundays with his flowers. He sobs whenever the exhumation of her remains is mentioned. Of all the things done to him, he says, ‘digging her up was the worst. You would think they could leave her in peace.’

His greatest distress is that her death became such a public issue. These were matters that he’d resolved should remain private to protect their son from discovery when he grew older. He curses the media campaign and those who caused it for putting Sam at risk through their disregard of his welfare.

11 Poster of baby with gun (obtained under FOI)

12 Bill Kerr’s note on Adams/Smith conversation (obtained under FOI)