Chapter 7

The First Tanner Investigation

Friday 16 November 1984

Two days after Jenny Tanner’s death, Dr Peter Dyte, the Shepparton pathologist, performed an autopsy on her body. When he cleaned the head wound, he was surprised to find two bullet holes and immediately rang the Mansfield police to check that they had no suspicions.

I knew Peter Dyte. He performed several autopsies for cases I investigated, and he occasionally invited me to be present. He was a meticulous pathologist who’d trained under Victoria’s master forensic pathologist, Dr Vern Pleuckharn.

Unfortunately Dyte developed cancer before the first inquest and died shortly afterwards. He was therefore unable to give evidence and defend or explain his examination and findings. The debacle of the second investigation might never have occurred if Dr Dyte had been healthy for the first inquest. Instead, others speculated about what had happened, and some questioned his post-mortem report.

Dr Dyte observed that the bullet holes had close but separate entry points. He sent the body to radiology to have the skull X-rayed. The two bullet holes were contrary to the information in Kerr’s Report of Death form, so Dyte rang the Mansfield police. He first spoke to Don Fraser, who told him that Sergeant Phipps had been ‘with me’ the previous night before handing the phone to Phipps, who tape-recorded the conversation. Phipps spoke with the authority of one who had attended the death scene. Dr Dyte told him:

There’s certainly two definite wounds in the forehead of this lady…apparently she wasn’t cleaned up before she was looked at…They’re quite close together…only a few centimetres apart, but there are two quite distinct wounds, which look like entrance wounds. The other pathologist and I both looked at it and we feel that it is consistent with her holding the gun up to her head and firing twice…which would be quite possible as I was saying before, she could still be alive after the first one, particularly in that area…I’m getting the skull X-rayed at the moment.

The ‘other pathologist’ was his assistant, Dr Norman Sonnenberg, whom he called in to sight the two bullet holes. Sonnenberg was also present later, when the brain was examined, but he didn’t witness the entire autopsy.

When the body was returned to the mortuary after the skull X-ray, Dr Dyte conducted the autopsy and found two fragmented bullets lodged in the skull. The lower one was just beneath the frontal lobes and had bruised the brain’s undersurface. The second bullet was slightly higher and had fragmented in the midbrain. He called the Mansfield police again and this time spoke to Fraser, who again recorded the call:

Dr Dyte: I’ve just finished the autopsy. I found two bullets inside her skull…the wounds were mainly on the undersurface of the brain. There was a little bit of an area in the midbrain which is a vital structure area, but most of the bruising, most of the area was in my opinion, confirms the possibility she could of, you know, fired again.

Fraser: Right, so there is a strong chance that she would have been still alive after that first shot.

Dyte: Yes. That’s a reasonable way to put it.

Fraser: Um – do you think the bullet holes in the hand have come – uh – no way of telling if that was the result of the first or second shot?

Dyte: No – uh – possibly the second shot, I think. Because there’s much more powder burns on one, on the first shot I think, or what I think is the first shot.

Note that Dr Dyte didn’t say that Jenny shot herself twice. He’d said that there was a possibility that she was capable of firing the second shot. His function was to establish cause of death, not to speculate on manner of death; that was the job of the police investigation.

Dr Dyte posted his post-mortem report to Kerr; it was written in medical terms. Apart from the two head wounds and the two hand wounds, Jenny had no other injury. He concluded that she’d died from ‘gunshot wounds to the head with gross cerebral contusion’. His report didn’t express an opinion regarding her ability to fire a second shot. He’d done that in the telephone calls to police and would normally express his opinions on such subjects in person at an inquest.

When Phipps and Fraser received these telephone calls from Dr Dyte, the buck clearly stopped with them. Kerr couldn’t be blamed, because he wasn’t working until 5 pm that day. This call meant that the bullet or bullets that caused the hand wounds hadn’t been accounted for, nor had the other spent shells.

A full-scale search of the scene should have commenced immediately, and the body shouldn’t have been released until this was done. The evidence would have all been intact in the house, because it was locked. Apart from some of the blood that Bruce Tanner had wiped from the couch, the police already had Jenny’s clothing, the headshot bullets, two spent shells, the poster and the rifle. Welch should have been immediately recalled for what was now a suspicious death.

Phipps told the second inquest that the reason he hadn’t done this was that Duncan MacLennan, the inspector at Mansfield, had told him not to get involved because he was transferring out that day. But this excuse doesn’t hold water because, if Phipps had recalled Welch, responsibility for the investigation would have transferred from the uniform branch to Welch, the detective.

When Bill Kerr started work at 5 pm, Phipps and Fraser would (or should) normally have told him about the two bullets. But this shift was Phipps’s last at Mansfield, so it could be that others, in line with police custom, took him for a few after-work drinks, and he may not have encountered Kerr before he finished. In that case, the responsibility for telling Kerr transferred to Fraser.

Because Phipps had finished at Mansfield, the other Mansfield sergeant, Doug McPhee, should have assumed oversight of Kerr’s investigation. And when Kerr was told about the two bullets, he should have immediately told Welch. Whoever was at fault, Welch wasn’t recalled before the body was released to the undertakers.

Kerr seems to have been on his own from that point: Senior Sergeant Neil Walker didn’t return from leave until the following Monday, and for the three months starting on Saturday 19 November, Doug McPhee was the only sergeant at Mansfield. At the second inquest, McPhee emotionally denied having any involvement in or oversight of Kerr’s investigation and inquest brief; but that was his job as the supervising sergeant.

Later, in a sworn affidavit, Inspector Peter Mangles described the style of questions on this matter at the inquest as being so intimidating ‘that some police who had acted honestly in supervising Bill Kerr in 1985 were reduced to tears sooner than face the ridicule of telling the truth.’

In fairness to McPhee, Kerr didn’t readily accept help or advice. He did things his own way and would present all manner of excuses and positive assurances to stop others becoming involved. His approach was exemplified by his decision to keep the two bullets in Jenny’s skull a secret from her relatives for another ten months. It was no wonder that her family was angry and suspicious when he so belatedly told them.

Kerr’s notes show that he interviewed Hugh and Val Almond on his Friday afternoon shift. Earlier in the day Fraser had taken statements from Dr Gilham and Angela McCormack.

On that afternoon the Tanner brothers went to Springfield to start cleaning the house and tend the stock. They placed the couch on the front veranda and covered it with a sheet; it stayed there for a year, then was stored in a shed, where it remained until it was burnt.

Saturday 17 November 1984

Both Jenny’s funeral service and the Mansfield Show were held on this day. Laurie was heavily sedated and has little memory of anything. Show society members briefly joined mourners at the Tanners’ home to pay their respects after the funeral, and then went back to running the show. The Tanners later joined other mourners at the Blakes’ home.

Senior Constable Kerr was rostered to work from 10 am at the Mansfield Show.

Sunday 18 November 1984

On this day Bill Kerr took statements from Hugh Almond and Laurie Tanner. These statements and a very brief one from Lyn Timmins were his only contribution to his eventual inquest brief. He didn’t take a statement from Mrs Almond, although he made note of her extensive comments.

During the day Denis took Laurie to the police station to make his statement. Laurie was distraught; he was mortified by the prospect of publicly revealing his wife’s behavioural changes, and he didn’t want his son to blame himself for contributing to his mother’s death when he was older. He asked Denis how he could protect Sam. Denis says that in these discussions he may have said, ‘There is no need to go into the specific details of your private life.’ The second Coroner interpreted this comment as sinister, but it was simply Denis’s way of reassuring Laurie that his evidence needn’t expose his infant son.

Kerr also taped this conversation and handwrote Laurie’s statement. My transcript of that tape runs to sixteen pages. The conversation was uneventful and friendly, with Laurie recounting events on the day Jenny died; he was very upset and cried quite a lot. Denis made him a cup of tea and offered to make coffee or tea for Bill Kerr. The tape is an hour long, with a lot of quiet time when Kerr is out of the room. It shows a country copper tactfully trying to piece a statement together from a distraught witness.

It also shows Denis’s scant involvement in the process. While Kerr was interviewing Laurie, Denis had asked for permission to use the station telephone. He can be heard in the background unsuccessfully trying to have a report supporting his Mansfield sergeant’s application on compassionate grounds delivered to headquarters by a mobile traffic car. He can also be heard ringing a friend who owned a property at Ocean Grove to make arrangements to take Laurie away for a few days. He gave Bill Kerr details and the phone number of the property in case Kerr needed to contact Laurie during the following week.

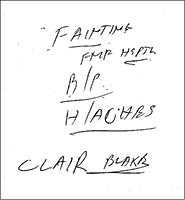

Bill Kerr’s notes record these numbers, but they also include quotes from Jenny’s sister Clare indicating that she told him about Jenny’s fainting spells, blood pressure and headaches and also mentioned Mansfield Hospital (see Image 15). Kerr didn’t take a statement from Clare.

19–20 November 1984

Monday 19 November was the first day that Laurie ventured back to Springfield. Kath Blake had insisted that Laurie meet her at the farm that morning while Mrs Blake went through Jenny’s things. Laurie describes it this way: ‘Her mother insisted I had to be there at the house on the Monday, so Kath and the sisters came out to Springfield and they just took everything…They took all of our cutlery and dinner sets, and Jenny had these camphor chests with clothing and sheets and blankets. When we were out there cleaning up on the Monday, they could hardly carry the boxes out.

‘I understand that Kath was upset like all of us, but she was just saying, “This might fit you” and “You can have that”, “I’ll have this” and all that sort of thing. I look back on it now and that was all my stuff that they took and, me being like I am, not wanting to make any fuss, I just let it happen.’

Laurie was left with almost none of Jenny’s possessions and very little to remind him of their marriage. He now has a wedding album that the Blakes returned some years later, but no photos of their honeymoon or holidays together. Sam came with the Blakes that day, and from then on he lived with Laurie and his parents.

Some time during the day Denis and Lynne went home to Spotswood to prepare for the Ocean Grove trip, calling en route at Victoria Police headquarters in William Street to lodge his compassionate grounds report to support his Mansfield sergeant’s application.

Late in the day Laurie and Sam left Mansfield for Ocean Grove. Laurie doesn’t drive in city traffic, so Denis met him at Mickleham and Laurie followed him to Spotswood.

Next morning Denis, Lynne, Laurie and their baby sons travelled to Ocean Grove to spend three days.

21 November 1984

The police tapes show that the Blakes had asked Laurie to tell the police about Jenny’s old injury. Laurie had earlier called Mansfield police and left a message for Bill Kerr.

Bill Kerr called the Tanners back at Ocean Grove on Wednesday 21 November. Again Kerr taped these conversations and took notes, which fill out sentences where some words are unclear on the tape. The tape wasn’t identified or transcribed for the second inquest. The Coroner ignored it in his finding and didn’t give the Tanners a copy of it. This is a précis of the conversations.

Denis answered the call while Laurie was changing the baby’s nappy. Denis told Kerr that Lynne also wanted to talk to him. While waiting for Laurie to come to the telephone, Denis and Kerr had a short and friendly conversation about the sergeant’s vacancy at Mansfield. Denis revealed that he’d found out that Sergeant Terry Cahill from Greensborough would get the position.

Laurie came to the phone and said: ‘I had a bit of a chat with the Blakes yesterday, they just thought it might have, you know she might have been a bit depressed because of her fainting. When she was fifteen she had a bad fall off a horse, which dragged her two to three hundred yards in the stirrups.’

Laurie said that he wouldn’t be going home to Springfield for at least three weeks and would be staying with his parents. He told Kerr that his parents had the keys to Springfield if police needed to go back. Kerr rejected the offer: ‘If I need to borrow keys to check things in the house, I’ll contact you; that’s probably the easiest way.’

After Kerr and Laurie had finished talking, Lynne Tanner came to the phone; she’d previously worked with Bill Kerr at the breathalyser section. They had a light and friendly chat about her new baby, and Kerr offered parenting advice. Lynne told him she’d been concerned about Jenny’s depression and that she’d approached two police surgeons, Dr Bush and Dr Jappe, to get advice. She said that Jenny only really had two close friends, Ros Smith and Lyn Timmins, and that she hid her feelings, felt trapped on the farm and missed Melbourne. She also said Jenny was closer to her sister Kristine than she was to Miriam. The call ended with Lynne thanking Kerr for his compassion to the families. ‘Bye bye…listen Bill, thanks very much for your concerns.’ Kerr’s notes tell the same story.

•••

After this call Kerr went to Angela McCormack’s Mansfield home to go through the statement Don Fraser had drafted. He taped this conversation on the reverse side of the same Ocean Grove cassette. It runs for an hour. Angie told Kerr how Jenny didn’t like shopping in Mansfield and spoke of her frequent trips to Melbourne. Kerr told her that he was certain that Jenny’s death was a simple suicide:

Angie: Oh. It was definitely suicide, was it?

Kerr: It appears that way.

Angie: We were hoping it was murder…at least it would be something to go on to…I mean…(laughing loudly) it might have been in the day (laughing) but at least if had of been…then we’d know something.

Kerr: Well, I can’t make a decision on that, all I can do is compile a report that says…It’s up to the Coroner to say whether it’s a suicide, murder or what. But…to me…it is an open-and-shut suicide.

The tape also exposes the inaccuracy of Kerr’s later claim about Denis Tanner’s whereabouts on the night of Jenny’s death.

Kerr: I rang…Denis Tanner…

Angie Oh yes.

Kerr: I didn’t actually ring him. I rang his work station and got them to go and let him know. He didn’t know.

Angie: Shit.

Kerr: No-one had told him.

There was no mention of Tanner’s not being home when police called to deliver the message.

22 November 1984

Bill Kerr went to see the Blakes and taped the entire conversation from his knock on the door until when he drove off. The tape is exactly an hour long, but it wasn’t transcribed for the second inquest and was ignored in the Coroner’s finding. In every other taped conversation, Kerr took notes, but no notes of this conversation were in the file he presented to the second inquest.

The conversation tells a vastly different story from what Kerr and Kath Blake told the second inquest. Mrs Blake dominated the conversation and was obviously keen to control any evidence that would indicate depression or suicide. During the conversation her husband Les arrived home and the family related much detail of Jenny’s life, behaviour and character.

When Les Blake asked Kerr to explain how Jenny died, Kerr told them in the most matter-of-fact tone: ‘It appears to be a…without trying to sound harsh…an open-and-shut suicide. That is the way it appears.’ When he said this, he should already have known for six days that two bullets had been fired into her skull; but he still didn’t tell the family.

Les Blake repeated the story about Jenny’s fall from the horse and her recent fainting spells.

In respect of Jenny’s violent death, Mrs Blake said, ‘Well, I thought that perhaps if she thought that she would give [Laurie] a fright, and then did she fall asleep and it happened accidentally?’

Denis wasn’t mentioned during the conversation. At the end, Kath Blake gave Kerr the contact details of Jenny’s Queensland friend, Ros Smith.

•••

Later that evening, Kerr telephoned Ros Smith in Surfers Paradise; again he recorded the conversation. The tape proves that this was the first time Kerr and Smith had spoken to each other. This call is critical, because Smith and Kerr both claimed at the second inquest that she’d told Kerr of the alleged incident involving Denis Tanner’s spotlighting visit on the day after Jenny’s death. For that reason I reproduce the conversation in its entirety:

Smith: Hello.

Kerr: Senior Constable Kerr from Mansfield Police Station. I was looking for Roslyn Smith.

Smith: That’s me…

Kerr: Yes. Do you know about the death of Jenny Tanner?

Smith: Yes.

Kerr: Pardon?

Smith: I been very good friends of her…

Kerr: You’ve been very good friends of her?

Smith: Yes.

Kerr: Yes. Did you know that she’d died?

Smith: Yes.

Kerr: You did. Right. I‘ve got to…prepare a brief for the inquest. I’ve been told that you were very good friends with her and I was wondering if you could give me a rundown on what sort of a person she was like – whether she had any hangups or similar.

Smith: Can I just take my 5-year-old daughter outside, please?

Kerr: Yes. No worries.

Smith: I won’t be a minute.

Kerr: Right. (Pause)

Smith: I’m sorry about that – I didn’t want her to overhear me.

Kerr: Yeah. That’s all right. No worries.

Smith: It just doesn’t seem…you know…not her character to do something like that.

Kerr: Yeah.

Smith: She was up here…in June or July they stayed at that place for a week…in July…Jenny…I always assumed that she was happy. Loved her baby and house. There was no known hangups, depression, post-natal depression like some people. Nothing like that – she never ever mentioned it to me.

Kerr: Yes.

Smith: We talked all the time on the phone. I never. I didn’t find any…depression…you know, anything…like that. You know…we often had our gripes about everyday things but she was only normal, like me complaining about something.

Kerr: Yeah.

Smith: Is that the sort of thing that you want or…?

Kerr: Not really…Judging from what I have heard that you were fairly close.

Smith: Yes.

Kerr: I thought that she may have confided in you if she had any problems or anything along that line…ahm…problems with Laurie or with the baby or anything like that.

Smith: No. Like that’s something…that struck me…I know we would talk about people that gossip because we were a long way away but at different times…we heard that um…you know…that she thought about going to leave Laurie or something but I know nothing about that…in fact she was talking about having another baby.

Kerr: Yeah.

Smith: So when they were up that time, staying a week last year, I didn’t pick up on any marriage problems or baby problems or anything like that.

Kerr: Yeah. No worries. What would be your nearest police station up there?

Smith: Oh, Surfer Paradise or…

Kerr: Surfers. Yeah. That’s Surfers Paradise.

Smith: You know I can’t…I was so devastated. I got questions but no answers.

Kerr: Yeah.

Smith: But with something like that…

Kerr: Yeah. I know what you mean…um…What I might do…I might arrange for one local policeman to come around and see you and to get a statement off you as to how you found her, how you found her, um, her relationship between her and Sam, her and Laurie, the rest of the family, things like that.

Smith: Yes.

Kerr: And…um, you mentioned that um she was talking about having another baby?

Smith: Umm.

Kerr: Now, if you could include that in your statement as well.

Smith: Right.

Kerr: That’s the thing, and then I can get it sent down here. I’ve only got a month to get it all sorted out – that’s why I rang.

Smith: Oh, right, so…

Kerr: If you could give me some indication – this business about having another baby is good.

Smith: Yes, well I heard there will be an inquest, because my husband and I talked about it, and people who know everything say it’s cut and dried as to what happened…so I’m pleased about it…Thanks very much…If I can help in any way…you know I would be only too pleased to.

Kerr: Your address there. [He confirms the address – omitted.]

Smith: Yes, that’s right.

Kerr: Right. No worries…I’ll get onto the local police and get them to come around and I’ll give them a rundown on what the story is and they’ll get a statement off you for me.

Smith: All right. Thanks very much.

Kerr: OK. Thank you very much.

Smith: Bye.

This tape shows that Denis Tanner wasn’t mentioned at all.

Again Kerr’s notes match the taped conversation; the only difference is the words ‘J. Fears – labour – childbirth’, to the left of the notes; I interpret that to mean ‘Jenny fears her child may have been affected during labour’, an observation that fits with the information Kerr later passed to Detective Welch. It was probably included in Kerr’s notes as a result of his conversation with retired Mansfield policeman Geoff Adams the following evening.

23 November 1984

Kerr’s notes show that Geoff Adams spoke to Kerr at 8.50 pm on 23 November after taking a call from Ros Smith and her husband. This was when Adams reported that Smith had said Jenny believed her baby had a birth defect caused by being short of oxygen, and that the baby was easily upset and cried a lot. The only mention of Denis Tanner was that he’d called Ros Smith on Sunday 18 November, asking if she knew whether Jenny had made a will. Smith had described this as ‘fishing’.

In a report dated the same day, Kerr sent a file to Queensland police requesting a statement from Smith. The report expressed the view that Jenny died from ‘self-inflicted gunshot wounds’ and mentioned ‘Jennifer’s fears and apprehensions regarding her childbirth labour’. The issues raised in the notes were never addressed during the second inquest; nor were they mentioned in the statements by Geoff Adams, Kerr or Smith.

It took four months for Smith’s statement to be returned to Victoria, and when it arrived, it told a different story from their taped conversation, Kerr’s notes and Smith’s relayed conversation with Adams. Smith now claimed that she’d spoken to Jenny ‘two days after daylight saving started’. This means the date would be Tuesday 30 October, as daylight saving had started the previous Sunday, but Smith insisted that the date was a week earlier. She claimed Jenny had told her that Denis had called in at dusk the previous night, discussed the trouble Jenny was having putting Sam down because of daylight saving, then asked for the rifle so that he could go spotlighting. She said that, with the rifle in his lap, Denis had questioned Jenny about whether she was going to leave Laurie. Jenny had told Denis to mind his own business, and later told Laurie, who became enraged at Denis.

Denis did call in on Monday 29 October, after daylight saving commenced. He was on leave and had delivered a load of plaster for the renovations to his own property next door. He says he called in to Springfield to say hello, as he always did. Laurie wasn’t home, so he waited a while, played with the baby and left. He says there was no rifle and no angst, but they did discuss daylight saving and the trouble it caused Sam.

There’s no doubt that the correct date of this visit was Monday 29 October, because Laurie was at an Apex meeting. The meetings were held fortnightly, and this was an Apex night. There was no Apex meeting on 22 November, so Smith had the date wrong.

But the real issue is her story about the rifle and the spotlighting. Kerr’s notes show that by the time Smith made that statement, Geoff Adams had told her about the two head bullets. Like others, she would have found it difficult to reconcile how Jenny could have shot herself twice. At the inquests she wasn’t called on to explain why she didn’t tell Senior Constable Kerr about Denis’s visit when he first rang her, eight days after Jenny died.

Laurie denies Jenny told him anything other than that Denis had called in. To him this wasn’t unusual, because Denis was coming and going every few days to work on his own house. The date was special, though, because it was Laurie’s birthday the next day, 30 October. That day Jenny phoned Lyn Timmins for her birthday; they discussed plans for the following year’s joint birthday and the fun they had catching up, but Timmins said that Jenny made no mention of Denis Tanner’s visit.

If Smith’s version of Denis’s visit is correct, why didn’t Jenny tell Laurie, her family or her other friends about it? And why would she have asked Denis to be her child’s godfather?

Smith’s story is also flawed because Denis couldn’t have gone spotlighting. He’d have needed a four-wheel drive and at least two others to drive and hold the spotlight, and to leave the property he’d have had to go back to the Springfield homestead. He’d also have had to return the rifle. Nothing fits.

When I went through Smith’s statement with Laurie Tanner, he addressed many issues that he had with it. For example, Smith claimed: ‘Jennifer and Laurie went to visit me at Sorrento Waters [Surfers Paradise] a number of times over the last year.’ In fact, Laurie says that they only went there once before they were married and once in July 1984, when they stayed in Dr Kemp’s unit.

Smith said: ‘Jennifer enjoyed living on the farm.’ Yet most people who made police statements said that Jenny hated the farm life. Smith’s claim that ‘Jennifer did not want to live in a close neighbourhood’ was also incorrect. That’s exactly what she wanted to do. At Surfers, Jenny tried to talk Laurie into selling up, moving to Queensland and getting a nine-to-five job.

Smith had said that on the night of Denis’s visit, ‘Jennifer stated she drove Laurie into Bonnie Doon to a meeting’. But she didn’t take Laurie into Bonnie Doon; he drove himself to an Apex meeting in Mansfield. If Jenny had collected him after the meeting, she would have had to drive into Mansfield with the baby and wouldn’t have been home when Denis visited.

‘Jennifer decided to light the wood stove, but first she had to collect some wood out the rear of the house.’ This was also wrong. The combustion stove in the kitchen never went out because it provided the hot water. There was a wood box next to the stove that Laurie’s father filled every day. Laurie said, ‘She would have let the fire go out sooner than go outside for wood. The reason for her going outside the back door would have been the dogs chained under the cypresses; they always barked madly when anybody approached the house. She hated them.’

And so it went on paragraph after paragraph. At every point, Smith’s statement was factually wrong.

It is logical to assume that the issue of the two bullets troubled Ros Smith when Adams told her about it, as would her recall of Denis visiting after dark. Not knowing that Denis was renovating his own house next door, she’d wonder why he was there so late at night. Spotlighting would also resonate with Ros Smith because her first husband had made his living as a rabbit shooter in these hills.

Laurie makes the general comment about Jenny: ‘Does anyone really think she would stay in that house on her own if she had been threatened? I think not! She was a very strong-willed person. For that matter, there is no way I would leave her and the baby in that house if there was any sort of threat made.’

Smith also misled author Robin Bowles, who quoted her in Blind Justice as saying:

I only ever met Denis once. He didn’t come to the house often as far as I knew. He’s big with short hair and he’s very broad; looks very strong. I was a bit ambivalent towards him then. I didn’t warm to him. Later on I hated him.

Smith repeated this line in her television interviews.

The truth was that Ros Smith did know Denis Tanner because they’d been in the same class at Mansfield High School for four years. Smith seems to have disliked Denis long before she made these claims against him. When Jenny and Laurie were married, Jenny told him Smith had refused to attend their wedding because Denis was best man.

Denis Tanner has no idea what the conflict was about. He thinks that it may stem from a time when he was working as a part-time barman in a local hotel, before he joined the police; he may have once refused to serve her or one of her friends.

Smith told me that Denis Tanner was a monster, but later added that she didn’t really know him. When I raised Kerr’s tape of his telephone call to her, she declined my request for a videoed interview, claiming that she’d never been previously told that her telephone conversation with Kerr was taped.

The passage of time affects memory, but it is often said that if you tell a story often enough you can end up believing it. Clearly, in Kerr’s taped call and his notes, Smith initially claimed to know nothing. On the following day she passed a message to Bill Kerr through Geoff Adams in which she told of Jenny’s fear for her child, and Kerr’s notes indicate that Geoff Adams told her about the two headshots. Her story about Denis Tanner’s visit came much later, after Kerr’s request to have her interviewed was sent to Queensland.

A question Mr Rapke asked of Smith during her second inquest evidence suggests that he was aware that her evidence conflicted with Kerr’s notes and reports. He asked: ‘Did she ever say anything to you, which suggested that she believed or had fears, that her child was retarded, either physically or mentally?’ Smith replied, ‘No, she did not.’ The conflict wasn’t pursued with Smith or Kerr, and Adams wasn’t called as a witness.

Bill Kerr’s call to Roslyn Smith was the last of his taped conversations. If he took others, the tapes and notes have disappeared or been withheld. Apart from Jenny’s Melbourne friend Lyn Timmins, he took no further statements and has no notes of interviewing anyone else.

15 Bill Kerr’s note of remarks by Jenny’s sister Clare (obtained under FOI)