Chapter 8

The Homicide File and the First Inquest

The return of Ros Smith’s statement obviously worried Bill Kerr and made him wonder if he’d made a mistake in declaring Jenny’s death a simple suicide.

I spoke to Senior Sergeant Neil Walker, who said he’d felt Kerr should be relieved of the job and told Duncan MacLennan, the inspector at Mansfield, that it should be given to Detective Sergeant Ian Welch. Walker said that after consulting his superiors at Benalla headquarters, ‘MacLennan insisted Kerr should complete it. I now know MacLennan denied that at the second inquest; the mistake that I made was not putting this on paper.’

Welch was on sick leave from early January until April being treated for cancer, so these administrators may have been concerned about his health and welfare.

Whatever happened, the Smith statement meant that Denis Tanner now had to be interviewed. Kerr was also in order to look for a motive for Denis Tanner to murder Jenny, but he didn’t undertake even the simplest enquiries. He resorted to guesswork and theories about what might have happened instead of making investigations or reviewing the material already gathered in the days after Jenny Tanner’s death. He failed the sergeant’s course twice during this period, and I suspect the pressure may have affected his health.

In mid-April 1985 relieving Inspector Peter Mangles asked Kerr what was holding up the inquest brief. After being shown Smith’s statement, he directed Kerr to prepare a report to have Tanner interviewed by an officer. The homicide file that evolved became the subject of dispute, sensationalism and innuendo during the second inquest.

On 19 April 1985 Kerr put together a file containing the few statements he’d taken, his own statement and a list of twelve questions:

1 Is there any proprietary interest in the property ‘Springfield’ held by Dennis Tanner or his wife Lyn? [sic]

2 Is there any possible future interest in the property held by Dennis or Lyn Tanner?

Both these questions could easily have been answered by Kerr’s examining council rate records or title documents for the property. In both cases, the answer would be ‘no’. Laurie had bought out Denis’s interest in Springfield before he married Jenny.

3 Is the allegation that Dennis attended at the Bonnie Doon home on the night of the 22nd of October 1984 unannounced true?

This was Ros Smith’s allegation.

4 If true is this a normal pattern for Tanner to follow?

5 Is the allegation that he told his wife Lyn that he was going to the races true?

Smith had claimed that she’d heard from Jenny that Tanner had told Lynne he was going to the races.

6 If so could the statement by Tanner that on the night of the deceased death that he went to the races be true or false?

7 What were Dennis Tanners movements on the night of the deceased death? Can they be substanciated?

If Kerr had listened to the taped interview with Denis on the day after Jenny’s death, he’d have found that Denis had never been asked to account for his movements that night.

8 What was the topic of the conversation with Laurie on the phone at about 5.30 pm that night?

This question had already been answered in the various tapes Kerr made on 15 and 18 November. Indeed, Kerr himself had shown he already knew the answer before then, when he summarised the purpose of that phone call to Denis on the day after Jenny’s death: ‘You said he better go and get the horse in.’

Kerr’s next four questions, as he said himself, were based on ‘rumour and conjecture’ about a possible motive for Denis to murder Jenny. They began with the mistaken assumption that Denis had a financial interest in Springfield and went on to speculate that Jenny and Laurie were close to breaking up:

9 Could a possible financial interest in the property ‘Springfield’ present of [sic] future and the possible threat of further financial burdens on Laurie and the family property be sufficient motive for Dennis to contemplate the commission of a serious crime?

10 Was the fear of a possible marriage breakup so strong as to require drastic action?

Kerr had no witness statements or evidence to support his next allegation:

11 It has been alleged that there was no love loss between the deceased and Dennis. Is this true?

His final question was simplistic in form:

12 Did Dennis Tanner in fact attend at Bonnie Doon on the night of the 14th of November, 1984, and point the rifle at the deceased when it went off?

Kerr went on to observe that it wasn’t generally known that the deceased had two gunshot wounds to the head. He added: ‘although the doctor performing the autopsy believes that what he considers to be the first shot would not have killed Jenny’, Kerr himself believed it would have had a ‘telling impact’.

The file went through the police chain of rank to Detective Sergeant Welch at Alexandra.

On 30 May Welch went to Shepparton and interviewed pathologist Dr Dyte, who reiterated his belief that Jenny may have been capable of reloading the rifle and self-inflicting both head wounds. He restated that the first and lower headshot bullet had only damaged the frontal lobes and bruised the undersurface of the brain. He quoted from a reference book by Dr Vernon Pleuckhahn: ‘Presence of multiple gunshot wounds in the deceased also does not necessarily rule out suicide’. The two men talked a bit more about how the first shot might have affected her:

Dyte: It’s possible that she was, her brain was stunned and it’s also possible she could have lapsed into unconsciousness.

Welch: Uh…It could have been either way?

Dyte: Lodged…perhaps enough to be able to do it again.

Welch taped that conversation.

According to Welch, Dr Dyte gave him a copy of the skull X-rays and a copy of his handwritten working notes, including his sketches of the hand wounds, the bullet paths and where the bullets had lodged in the skull. He may also have given Welch the two bullets/fragments recovered from the skull. This is consistent with the tape, in which Dr Dyte appears to be handing items to Welch as he made his parting comments. Welch said, ‘Well, thanks very much for your time’, to which Dr Dyte replied, ‘These are all yours.’ The Kale Taskforce mistakenly transcribed Dr Dyte’s words as ‘Is this the…is it.’

Welch later showed the X-rays to Senior Sergeant Walker at Mansfield police station. Neil Walker told me: ‘I recall this distinctly because I had never seen X-rays like that before or since. It is the only time I have ever seen skull X-rays. I could see the bullets and fragments suspended in the brain.’

Later, at both inquests, Dr Dyte was criticised for not taking these X-rays, yet he’d mentioned them in his tape-recorded phone calls. When I started investigating the case, I set out to find them. Tanner and I went to the Ombudsman to point out that they’d been mentioned at the time and Walker remembered seeing them. An investigator in the Ombudsman’s office took months to reject our claim that the X-rays had been taken, but we persisted.

Eventually, the Ombudsman went to the hospital at Shepparton and found the original X-rays where they should have been: in the hospital radiology archive. Walker had described them to me perfectly. The Ombudsman’s investigator told us that the Kale Taskforce had never actually gone to the hospital to search for these X-rays; they’d telephoned and were informed that they couldn’t be found. But the hospital radiology department told Laurie and me that three Kale detectives had spent four days searching through all the X-ray files.

After Welch received the material from Dr Dyte, he prepared an overview of Kerr’s file, but his tape reveals that he made a mistake in his report. He quoted Dr Dyte as telling him that ‘both bullets traversed horizontally to the back of the skull’. Unfortunately he misquoted the doctor; the crucial word on the tape of Dyte’s remarks is shown in bold below:

Welch: Were you able to get any line on the path of the bullet, the angle perhaps?

Dyte: It’s virtually gone straight in…I think that…the first shot probably went underneath the brain and I think the second shot’s hit the midbrain, which is a vital area.

Welch: How far did they penetrate?

Dyte: Look, I haven’t actually measured that. It didn’t go right through to the back, though. The first shot went right underneath.

The Kale Taskforce transcribed this tape for the second inquest, but their transcript replaced the word ‘didn’t’ with its exact opposite, the word ‘did’, so that Dyte appeared to have said, ‘It did go right through to the back’. Without the X-rays, working from a mistranscribed tape, all the experts who gave evidence to the second inquest, and even the Coroner himself, made or accepted the incorrect assumption that the bullets had traversed horizontally to the back of the skull. In fact, the bullets had not; the fatal bullet was suspended in the midbrain, while the other was suspended much lower and more to the front of the brain.

Welch added his report to the file, which was passed to Detective Senior Sergeant Jim Fry at the homicide squad, the squad’s longest-serving detective at the time. Though he copped flack at the second inquest for the fact that he didn’t conduct a formal question-and-answer interview with Tanner, Fry didn’t have the rank to interview police for a possible criminal offence. Police Standing Orders required this to be done by an officer of at least inspector rank. Fry’s role was to examine the file, take a statement from Tanner, address the murder or suicide prognosis and report to superiors.

Jim Fry had never heard of Denis Tanner; he made enquiries and applied his vast experience in gunshot deaths to the evidence in the statements before asking Tanner to come to his office on 20 May 1985. His questions to Denis followed the order of Bill Kerr’s list, though he didn’t ask Denis about the claim he’d told Lynne he was going to the races.

Fry later said that the question hadn’t been in the list he received. There may have been more than one version of that list, because there were several drafts of it in Kerr’s file. It’s of particular note that the folio number on that page wasn’t in the handwriting of Regional Detective Chief Inspector Tom O’Keefe, who numbered the pages throughout the file.

Tanner accounted for his movements on the night Jenny died, saying he’d been at the bingo game in Middle Park; bingo organiser Jack O’Hanlon confirmed this. Fry took a statement from Tanner and then reported to superiors that the indicators in the file showed that apart from her child, Jenny Tanner was alone in the house when she died. From the evidence contained in the statements on the file, there was nothing to indicate murder.

Fry agreed with Kerr’s own comment on the file, that Kerr’s jumbled list of unanswered questions ‘are based on rumour and conjecture and not direct or indirect evidence’.

The file returned through the chain of rank to Mansfield police station, where Kerr was directed to complete the inquest brief. Not one of the eight high-ranking detective officers or the clerks who examined that file as it passed through the chain of command noted any conflict with Denis Tanner’s alibi for the night Jenny died.

Nine days later, Kerr submitted the inquest brief without taking any further statements. Inspector Peter Mangles, who was again relieving at Mansfield, authorised the brief on 5 July 1985 and directed Kerr to prepare two copies of it on deposition forms for the Coroner at Shepparton.

•••

The inquest hearing was set for 18 October 1985 at Mansfield, and the Assistant State Coroner, Hugh Adams SM, got the job.

When the inquest brief arrived at the Melbourne Coroners Court, the newly appointed Coroner’s assistant, Senior Sergeant Peter Fleming, hit the roof. Nobody had told the internal investigations department that a member of the police force had been named in the investigation. He also found that the pathologist, Dr Dyte, had become terminally ill and couldn’t give evidence.

After discussing the unsatisfactory brief with the Coroner’s clerk, Fleming took the matter up with Chief Superintendent Vaughan Werner and Chief Inspector Walsh at internal affairs. Walsh felt that the brief should stay with Fleming and suggested he consult the homicide squad. Walsh’s action disproves Kerr’s claim that the version of his statement included in the file said that Denis Tanner had given conflicting alibis. If it had, Walsh would have directed that internal affairs immediately intervene.

Fleming went to the homicide office and spoke to Jim Fry, who stuck to his assertion that the evidence showed Jenny was alone. If a fault lies here, in hindsight Fry should have been called at the first inquest to explain his prognosis.

On the afternoon of 14 October 1985, Fleming discussed the brief with Coroner Adams. Mr Adams wanted the matter to proceed on 18 October for the sake of relatives and others in the country. He agreed that Fleming should make as many enquiries as possible before then; if other enquiries were required after he’d heard the evidence at Mansfield, he would adjourn the inquest to a later date.

Peter Fleming did a first-class job here. On 15 October 1985, the day after he’d spoken to the Coroner, he went to Jack O’Hanlon’s home in Middle Park and later took a statement from him. O’Hanlon again verified that Denis Tanner had been at the bingo on the night Jenny died. Fleming also went to see Dr Sonnenberg, Dr Dyte’s assistant, and obtained a statement, which supported Dr Dyte’s findings.

Fleming didn’t call O’Hanlon to the first inquest and the Coroner didn’t request his attendance, suggesting they both implicitly believed in the truth of O’Hanlon’s statement. At the second inquest, however, when Peter Fleming was under personal pressure, he made a brief comment that he had ‘some doubt about O’Hanlon’s reliability’. Fleming wasn’t demeaned as Walker, Welch, O’Keefe, Fry and others were.

Fleming also phoned Welch and asked him to make a personal statement, to get a statement from the ambulance driver, to find out what happened to the poster and how it got into the house at Springfield, and to prepare a plan of the house.

Welch prepared his own statement, contacted Fraser to draw the house plan, then discovered that the baby poster had been lost. He also rang Kerr at home, thereby discovering that Kerr hadn’t told the relatives that Jenny had two bullet wounds to the skull. He directed Kerr to tell them immediately. When Kerr did so, the relatives were stunned; who wouldn’t be? Kerr suggested that they engage a solicitor.

Mr and Mrs Blake immediately went to see local Mansfield solicitor Rodney Ryan, who was also Laurie Tanner’s solicitor. Ryan rang Laurie to check that he had no objection to him representing Mr and Mrs Blake. Laurie had none, but in the course of their conversation, Mr Ryan told him that Jenny had two bullets in her skull and advised him to seek representation himself.

Meanwhile, Fleming was still busy. He rang Dr Terry Schultz at Wangaratta Base Hospital to arrange for him to examine Dr Dyte’s report and attend Mansfield Court the next day to give an opinion. He also went to Parkville and took a statement from ambulance driver Gerry O’Donnell before heading to Mansfield to prepare for the inquest next morning. Fleming should get a medal for his efforts in those two days.

•••

Coroner Hugh Adams presided over the inquest at Mansfield on 18 October 1985. The hearing was finished by midday. There was no examination whatever about conflicting alibis or the ownership of Springfield.

Laurie Tanner told the Coroner: ‘I cannot think of any reason why Jenny would take her own life. All I can suggest is that it may have been brought about after the birth of Sam. She became very depressed and appeared to have two personalities. She would become very moody, but would hide her bad moods when we had company. I tried to get her to see a doctor in relation to this but she would not go. She insisted there was nothing wrong with her.’

Laurie also recalled what Jenny had said about Denis Tanner’s visit to Springfield on 29 October: ‘He walked across…to say hello and I was at Apex that night. He played with the baby, which he – he had not been settling down too well because of the daylight saving, and had a cup of coffee or something with Jenny and general discussion, I think, and waited around for me. I’m not sure what time he waited till but I got home fairly late that night from Apex and he’d gone.’

Hugh Almond, Gerry O’Donnell and Senior Constables Don Fraser and Bill Kerr followed. All agreed there was nothing to indicate any other person had been with the deceased, apart from the baby. Both hand wounds were through the webbing between the thumb and index fingers. Bill Kerr said, ‘It looked as though they entered from the palm side and exited from the back of the hand’ with ‘indents at the front and bone and flesh protruding from the rear.’

Kerr believed the black marks on the white towel in his drawing were powder burns, but he didn’t keep the towel. In evidence, he conceded that he didn’t really know what powder burns were, didn’t believe the deceased had left the couch and supported Fraser’s view that she may have lain to the left on the towel and the cushion. He said the blood drips down the side of the couch may have come from one of her arms or hands, and there was no sign of a struggle. He made no mention of Denis Tanner giving conflicting alibis; he wasn’t asked any questions by the Coroner, his assistant or legal counsel in respect of those issues that later became second inquest fodder.

Dr Gilham, who had certified death, followed. He gave the same general observations as others, varying only from their versions by saying there was an open biscuit barrel with the half-cup of coffee, not biscuits on a plate as Kerr and Fraser described. He added that a baby’s bottle and two fresh nappies were in front of the body. He said the police indicated that she had put the gun in her mouth and surmised that she had fired it with her toe.

Dr Terry Schultz, the Wangaratta pathologist, had examined Dr Dyte’s autopsy report and agreed that the cause of death was gunshot wounds to the head. He didn’t view the body and had only a brief telephone conversation with the ailing Dr Dyte that he said ‘achieved nothing’. Schultz said in his evidence:

The possibility of the wounds being self-inflicted cannot be excluded and there are many cases in the literature of suicide with multiple gunshot wounds. However in my opinion, I think it unlikely that the deceased would not have lost consciousness after the first wound to the head, whichever of the two it may have been.

He added that because Dr Dyte carried out the autopsy, nobody should discount his opinion.

Obstetrician Dr Geoffrey Patience from Benalla said that his first knowledge of Jenny’s death was when Senior Constable Kerr contacted him and ‘told me she had committed suicide’. He agreed that Laurie had earlier been to see him because he was concerned about Jennifer’s depression and his own knowledge of her reluctance to seek treatment. He said that Jenny hadn’t been keen to embark on another pregnancy following the caesarean and that she repeated this ‘several times when she came to see me with the son after the birth’. When she came to see him on 30 July 1984, however, she was considering having another baby and her mood seemed slightly less depressed.

Denis Tanner was mainly questioned about his knowledge of Jenny’s depression. He said: ‘I probably can’t enlighten the matter any further, except that just from the conversations I have had with my brother over a period of time since the birth, there was a distinct change in the nature of the deceased, in as much as at various times she would break out into – have arguments, it’d be – she’d use a lot of bad language, which was in his opinion, out of character. She would behave in an irrational manner…Jennifer wouldn’t go to a doctor for treatment because she believed there was nothing that could be done to assist her. It’d be a thing that would just fade away. That’s all.’

He was asked about when he’d called at Springfield. The date 22 October 1984 was mentioned, but when he was told that daylight saving started on 28 October, he said it could have been the Monday after that. ‘I have no entry in the diary; it’s just that I went back over the Mondays. I knew it was a Monday because…Laurie had been to Apex. I had a cup of coffee, we spoke about the baby and the difficulties she was having putting him down. She’d put him down at the older time, which was the time he was used to, and played with him for a while and we just generally talked. I had quite a good relationship with Jennifer and Laurie, as did my wife.’

Denis confirmed that on numerous occasions Jenny had visited their home at Spotswood and stayed with them, both before and after the birth. She’d sometimes stay for a week, sometimes more. After the birth of the baby, there were a number of occasions when both she and Laurie stayed and other occasions she was there by herself with the baby.

Angela McCormack recounted her telephone conversation with Jenny on the night Jenny died. She said Laurie left her home at 10 pm.

Roslyn Smith told of her long friendship with Jenny and repeated what she’d said in her Queensland deposition about Denis Tanner’s alleged visit to Springfield on 22 October. She said that Jenny didn’t say that Denis threatened her, just that he had the rifle on his lap and Jenny felt he was interfering in their life. She stuck to the date of 22 October 1984 and repeated the claim that Jenny had told her she’d taken Laurie into Bonnie Doon to a meeting and that her child wouldn’t go down at the normal time because of daylight saving.

Lyn Timmins and Jack O’Hanlon were on the witness list, but neither was called.

It is of note that during the first hearing, not one witness mentioned there being two bullets lodged in Jenny’s skull apart from a single sentence from Welch and the brief evidence of Dr Schultz. I mention this because Lynne Tanner was criticised at the second inquest for not knowing about the two headshots; it was said that she should have heard about them at the first inquest. The reality was that Lynne didn’t attend the first inquest and the relatives didn’t know themselves until two days before. The two bullets were mentioned in Dr Dyte’s report, so the Coroner, the police and counsel would have known, but observers in the court would have heard little to enlighten them.

At midday Mr Adams SM adjourned the hearing to a later date in Melbourne.

•••

Peter Fleming persisted in his attempts to fill in the gaps in the investigation. He took the Brno rifle from the Mansfield police store and delivered it to ballistics expert Adrian Barry at the State Forensic Science Laboratory two days later.

When the inquest resumed in Melbourne on 13 December 1985, Dr Sonnenberg told the Coroner that Dr Dyte had invited him to view and discuss the deceased’s injuries. In producing Dyte’s report, Sonnenberg said he’d perused it and had been present during part of the autopsy, but had only examined the head wounds, the brain and the hands, not the whole body: ‘The deceased had suffered two gunshot wounds to the head, one of which was fatal affecting the midbrain…sufficient to have caused death. The other appeared to be non-fatal with a path across the base of the brain, not hitting a vital structure.’

He said that during his discussions with Dr Dyte he was of the opinion that the deceased would probably have been able to inflict both wounds herself. Later, under cross-examination, he was firm in this belief. In respect of the two wounds to the forehead, he was unable to say which bullet was the one that passed through the non-vital area of the brain. Jenny had a wound to each hand through the webbing between the thumb and forefinger. ‘I think the entry wounds were more on the palmar surface, except that it’s caught a bit of bone as it’s gone through.’

He couldn’t say whether Dr Dyte took X-rays and photographs and didn’t know whether or not the police took the bullets from Dr Dyte. He wasn’t made aware of the existence of the tapes of Dr Dyte’s conversations.

Adrian Barry, a firearms and tool mark examiner from the State Forensic Laboratory, was the final witness. He gave evidence of his 26 October 1985 examination of the rifle given him by Fleming. I’ve already cited his evidence about blood on the rifle and the 15-degree vertical discharge of the last bullet fired.

Mr Barry also examined Dr Dyte’s report and gave an opinion that he believed there ‘might have been an obstruction such as a garment or cloth between the muzzle and the [hand] wounds for there to be no powder burns’. The white towel with two ‘powder burns’ drawn in Bill Kerr’s sketch of the scene could explain this.

Mr Rodney Ryan made a submission on behalf of Jenny’s parents. He said the Blake family wasn’t on a witch-hunt, but he pointed to unresolved questions. The evidence wasn’t conclusive, Dr Dyte hadn’t given evidence and the police investigation was inadequate; there were no photographs or measurements of the height of the couch seat or the length of the rifle, and no statements taken from her parents.

He applauded Senior Constable Bill Kerr for not concluding in his statement that the death was suicide. He criticised Dr Dyte for not taking X-rays (though Dr Dyte had). He also said that Dr Dyte had found that Jenny committed suicide, but this claim too was incorrect. Dr Dyte had simply given the police his opinion that Jenny wouldn’t have died instantly from the first shot and that she may have had the capacity to fire a second shot.

Mr Ryan asked the Coroner to bring in an open finding, and that was what Coroner Adams did. He was critical of the police investigation, but didn’t name individual police:

Now a lot of unanswered questions could have been resolved and suspicion removed from certain persons if proper initial investigations and tests had been instituted by the police officer concerned and the pathologist.

He summarised the evidence and made these comments about Denis and Laurie Tanner:

I am satisfied that this person [Laurie Tanner] had nothing to do with his wife’s untimely death and likewise the same in respect to Mr Denis Tanner. His movements on the night of the 14th of November have been investigated, his answers substantiated. I am satisfied that he was in no way responsible.

I find that Jennifer Ruth Tanner died on the 14th of November 1984 on a property known as Springfield situated on the Maroondah Highway at Bonnie Doon from the effects of gunshot wounds to the head and on the evidence adduced I am unable to determine if the wounds were self-inflicted or otherwise.

In the course of normal police process, this open finding wouldn’t be advanced further unless new evidence came to hand.

After the inquest, Fleming would have recorded the finding on the cover of the inquest brief and forwarded it through the command chain for notation of records. The document would later be archived at the district superintendent’s office in Benalla.

Getting on with life

The Blake family were unhappy with the first inquest result, and they weren’t the only ones. The Tanners, the Coroner’s office, police command and Mansfield police all knew that this unsatisfactory case reflected badly on the Victoria Police and left many questions unanswered.

Peter Fleming started the ball rolling by reporting the failures to his superiors. In response, Chief Commissioner Mick Miller required detectives to attend future suspected gunshot suicides and ensure that photographs, gunshot residue and ballistic tests were taken as a matter of course.

Laurie Tanner would never return to live at Springfield. In late 1985 he rented the homestead to some Mansfield police. Over the next two years he subdivided the property into ten blocks and progressively sold them to city people who wanted a block near Lake Eildon. In December 1992 he sold the homestead block to Max Harvey from Templestowe. For a time he leased back the shearing shed and some of the land.

He later purchased Preston, a much larger, well-appointed property in Howes Creek Road, closer to Mansfield and again close to Lake Eildon. Over the years he maintained his friendship with the Blakes, raised his son with his mother’s help and came to terms with his grief.

Bill Kerr

I knew Bill Kerr when he was at Mansfield and I was the detective sergeant from the neighbouring division of Benalla. Police have boundaries, but criminals and victims don’t, so that investigations regularly criss-cross territory. Bill was a compassionate person who’d do his best to help if he could, but he was also quite withdrawn. Superiors described him to me as pig-headed and difficult to manage, and some Mansfield police were reluctant to work with him, saying that he had seniority but limited general duties experience.

Like every large organisation, the police service is full of differing types: some work hard, others don’t; some are brighter than others; some strive for promotion and plot an ascending career path, whereas most are simply happy to serve the public and do the job they joined up to do.

Bill Kerr ran into real trouble when he transferred from Mansfield to Macarthur, a one-man station in Victoria’s Western District, two months after the first inquest. At Macarthur his ability to perform his police duties deteriorated to the point where his superiors were forced to counsel him, supervise his performance and eventually recommend his transfer to a larger station.

His last supervisor was Chief Inspector John Rankin from Hamilton (coincidentally, the same John Rankin he’d phoned at D24 to notify Denis Tanner of Jenny’s death). John Rankin tried to help Kerr by arranging for a sergeant from a neighbouring station to visit regularly and try to assist.

Chief Inspector Rankin told me: ‘We tried to give him help, but he resented it. He thought that we were riding him. I found it was quite interesting visiting his station: he had an extremely untidy place, absolutely shocking…He had a mob of sheep in the back yard of the police house, and they were using the cells as their shelter; this is true. I told him he had to get rid of them.’

Rankin went through the station while Kerr was there. He told me: ‘I discovered enough there to realise that he’d been out and attended quite a number of crimes such as theft of a battery, thefts of fuel, there was wilful damage to farm property – nothing on its own that was very big, but every one of them that was a crime he’d never told the CIB about. He’d never done a crime report or put in a running sheet about it; he’d never investigated it beyond writing in his spiral notebook – not his police notebook – and then doing not one other thing about it.’

Rankin looked after Kerr’s welfare, allowing him to use the police car to take his wife to Warrnambool Hospital for treatment. He arranged for the Police Credit Co-operative to lend him sufficient money to settle local debts, and sought help for his stress through the Police Medical Welfare office.

Despite these efforts, Kerr continued to run his own show in his own way, and he interpreted the help of Rankin, Chief Inspector Lindsay Florence and Inspector Frank Fox as bullying. Rankin told me that by mid-1993 he and Florence had no option but to recommend his transfer to Hamilton, a larger station where he could be supervised.

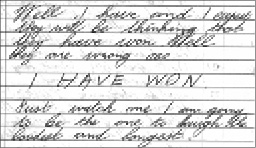

Kerr resented this, so in preference to the transfer he resigned from the police. In his official police diary he expressed a passionate dislike of his superiors in ten pages of rambling discourse. In the last entry, written on 22 June 1993 (see Image 16), he wrote: ‘I expect they will be thinking that they have won. Well they are wrong as I HAVE WON. Just watch me. I am going to be the one to laugh the loudest and longest.’

16 Bill Kerr’s diary, 22 June 1993 (obtained under FOI)