The notion that differences in education explain America’s growing inequality simply does not stand up to scrutiny, as explained by a Nobel Prize–winning economist.

The economist Dean Baker made a really good point when he wrote about how the Occupy movement that began on Wall Street framed the inequality issue. Occupy focused on “the CEOs, the Goldman Sachs crew, the lobbyists and the other members of the one percent who have done incredibly well in the last three decades,” Baker wrote and properly so.

Baker was chastising David Brooks, my fellow New York Times columnist, who wrote that these factors were not so important as “the gap between college-educated workers and those without a college degree.”

Brooks called the inequality that Occupy brought into focus “blue inequality” because the elites whose income and wealth are growing tend to live along the coasts in urban centers that vote Democratic. The gap between those without college degrees and those who earned them is what Brooks called “red inequality,” implying it is much more of a Heartland America concern.

The facts do not support the notion that education is at the heart of inequality. For starters, as Baker pointed out, “the ratio of the wages of those with just college degrees to those without college degrees has not risen much since the early 90s.”

It’s really awfully late in the game to be saying that the important inequality issue is college graduates versus nongraduates. It’s not clear that this was ever true, and it certainly hasn’t been true for a while.

I wrote about this in 2006, using Ben Bernanke’s maiden testimony as chairman of the Federal Reserve, as an entry point. As I said then, Bernanke—like many others—fundamentally misread what’s happening to American society.

What we’re seeing isn’t the rise of a fairly broad class of knowledge workers. Instead, we’re seeing the rise of a narrow oligarchy: income and wealth are becoming increasingly concentrated in the hands of a small, privileged elite. The proof is right in the data we economists get paid to analyze and understand.

I think of Mr. Bernanke’s position, which one hears all the time, as the 80-20 fallacy. It’s the notion that the winners in our increasingly unequal society are a fairly large group—the 20 percent or so of American workers who have the skills to take advantage of new technology and globalization—and that they are pulling away from the 80 percent who don’t have these skills.

Why would someone as smart and well informed as Bernanke get the nature of growing inequality wrong? Because the fallacy he fell into tends to dominate polite discussion about income trends, not because it’s true, but because it’s comforting. The notion that it’s all about returns to education suggests that nobody is to blame for rising inequality, that it’s just a case of supply and demand at work. And it also suggests that the way to mitigate inequality is to improve our educational system—and better education is a value to which just about every politician in America pays at least lip service.

The idea that we have a rising oligarchy is much more disturbing. It suggests that the growth of inequality may have as much to do with power relations as it does with market forces. Unfortunately, that’s the real story.

Let me illustrate this point with some Congressional Budget Office data. First, a report issued in October 2011, titled Trends in the Distribution of Household Income Between 1979 and 2007, breaks out the income shares of the top 1 percent and the rest of the top quintile (see the chart below). Notice that within the top 20 percent there has been no rise in the share of the 81st–99th group! It’s all about the top 1 percent. Second, even within the top 1 percent the gains are going mainly to a small minority at the top of that group.

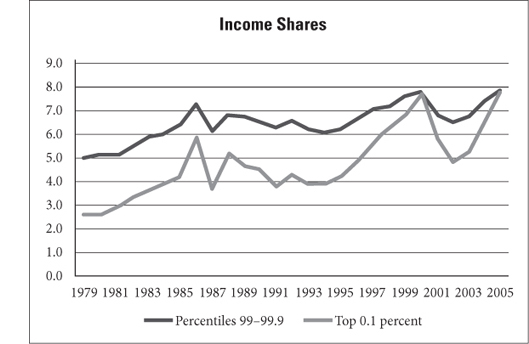

Another CBO report, Historical Effective Tax Rates, 1979 to 2005, issued in 2008, looked inside the top 1 percent up through 2005 using slightly different methods. On the next page is another chart with some of that data.

As you can see, the big gains have gone to the top 0.1 percent. In 2000 and again in 2005, the top 0.1 percent’s share of income was the same as the nine times larger group from 99.0 percent to 99.9 percent.

So income inequality in America really is about oligarchs versus everyone else. When the Occupy Wall Street people talk about the 99 percent, they’re actually aiming too low.

One last point: I see that David Brooks is arguing that the oligarchy issue, if it matters at all, is a coastal phenomenon, not the issue in the heartland. That is his “blue inequality” that “is experienced in New York City, Los Angeles, Boston, San Francisco, Seattle, Dallas, Houston and the District of Columbia. In these places, you see the top 1 percent of earners zooming upward, amassing more income and wealth.”

Let me point out, then, that we have one country, with a tightly integrated economy. High finance is concentrated in New York, but it makes money from the United States as a whole. And even when oligarchs clearly get their income from heartland, red-state sources, where do they live? OK, one of the Koch brothers still lives in Wichita; but the other lives in New York City.

Put it this way: having much of the wealth your state creates go to people who are in effect absentee landlords, whose income therefore shows up in another state’s statistics, doesn’t mean that you have an equal distribution of income. Out of state shouldn’t mean out of mind.

Look, I understand that some people find the notion that we’ve become an oligarchy—with all that implies about class relations—disturbing. But that’s the way it is.

A version of this chapter originally appeared on November 1, 2011, in “The Conscience of a Liberal,” the writer’s New York Times blog.