Donald S. Shepard, Elizabeth Setren, and Donna Cooper

The number of hungry Americans rose sharply with the Great Recession, exacting a costly toll in damaged lives and economic losses—about which it was easy to remain ignorant, as documented by three researchers in a study published by the Center for American Progress.

The Great Recession and the tepid economic recovery swelled the ranks of American households confronting hunger and food insecurity by 30 percent. In 2010, about 48.8 million Americans lived in food-insecure households, meaning they were hungry or faced food insecurity at some point during the year. That’s 12 million more people than faced hunger in 2007, before the recession, and represents 16.1 percent of the U.S. population.

Yet hunger is not readily seen in America. We see neither newscasts showing small American children with distended bellies nor legions of thin, frail people lined up at soup kitchens. That’s primarily because the expansion of the critical federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program helped many families meet some of their household food needs.

But in spite of the increase in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program funding, many families still have to make tough choices between a meal and paying for other basic necessities. In 2010 nearly half of the households seeking emergency food assistance reported having to choose between paying for utilities or heating fuel and food. Nearly 40 percent said they had to choose between paying for rent or a mortgage and food. More than a third reported having to choose between their medical bills and food.

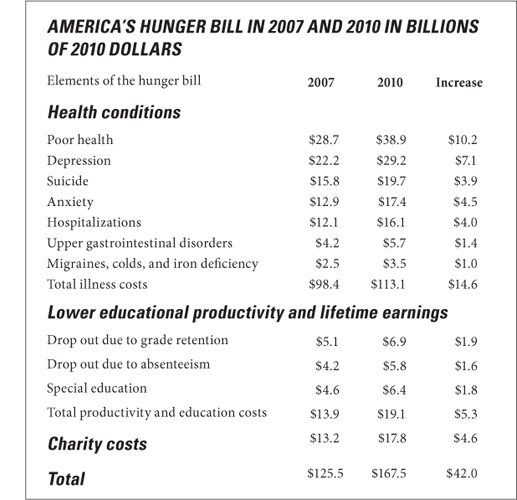

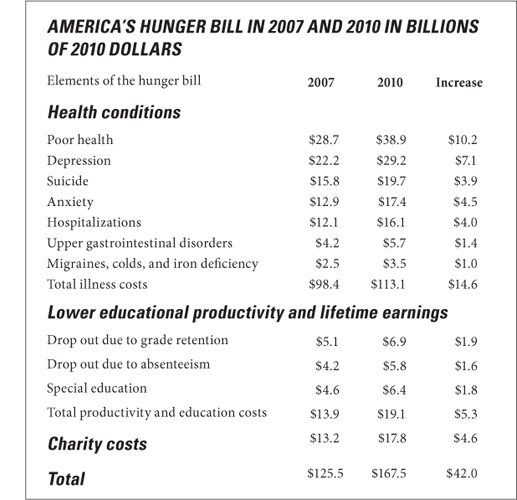

What’s more, the research in this paper shows that hunger costs our nation at least $167.5 billion due to the combination of lost economic productivity per year, more expensive public education because of the rising costs of poor education outcomes, avoidable health care costs, and the cost of charity to keep families fed. This $167.5 billion does not include the cost of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and the other key federal nutrition programs, which run at about $94 billion a year.

We call this $167.5 billion “America’s hunger bill.” In 2010 it cost every citizen $542 due to the far-reaching consequences of hunger in our nation. At the household level, the hunger bill came to at least $1,410 in 2010. And because our $167.5 billion estimate is based on a cautious methodology, the actual cost of hunger and food insecurity to our nation is probably higher.

This report also estimates the state-by-state impact of the rising hunger bill from 2007 through 2010. The rise in America’s hunger bill since the onset of the Great Recession affected every state. Fifteen states experienced a nearly 40 percent increase in their hunger bill compared to the national increase of 33.4 percent. The sharpest increases in the cost of hunger are estimated to have occurred in Florida (61.9 percent), California (47.2 percent), and Maryland (44.2 percent).

Our research in this report builds upon and updates a 2007 report, The Economic Costs of Domestic Hunger, the first to calculate the direct and indirect cost of adverse health, education, and economic-productivity outcomes associated with hunger. This study extends the 2007 research, examining the recession’s impact on hunger and the societal costs to our nation and to each of the fifty states in 2007 and 2010. It also provides the first estimate of how much hunger contributes to the cost of special education, which we found to be at least $6.4 billion in 2010.

The 2007 report estimated America’s hunger bill to be $90 billion in 2005, sharply lower than the $167.5 billion bill in 2010. We argue that any policy solutions to address the consequences of hunger in America should consider these economic calculations. The reason: we believe our procedures for expressing the consequences of this social problem in economic terms help policy makers gauge the magnitude of the problem and the economic benefits of potential solutions.

In this paper we do not make specific policy proposals beyond adopting our methodology for calculating hunger in America, but we do point out that expanding the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program to all food-insecure households could cost about $83 billion a year. While we do not recommend this approach, we note that nonetheless it would cost the nation much less than the most recent hunger bill in 2010 of $167.5 billion.

There are other policy approaches that also could achieve sustained reduction in hunger and food insecurity—approaches that rely on a mix of federal policies to boost the wages of the lowest-wage earners, increase access to full-time employment, and modestly expand federal nutrition programs. These policies are consistent with the variables used to allocate federal nutrition funding to states under the Emergency Food Assistance Program. In using the state’s poverty and unemployment rates, this program recognizes that improved economic conditions reduce hunger and the need for emergency support.

Our calculations based on our research enable us to break out the consequences of hunger and food insecurity in America fairly rigorously (see previous page).

If the number of hungry Americans remains constant, on a lifetime basis, each individual’s bill for hunger in our nation will amount to about $42,400 (based on the average life expectancy of 78.3 years per the U.S. Census Bureau).

Of course, the average American doesn’t receive a real bill for these costs. Instead, the costs are reflected in taxes, our contributions to charities that address hunger, and the costs paid directly and indirectly for the poor health condition of those who are hungry and their lower productivity.

Federal programs can and do address hunger and food insecurity directly. To a large measure they help mitigate enormous economic and societal costs of hunger. For instance, without federal funds supporting the more than 42 million Americans with Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, America’s hunger bill would have skyrocketed. If high levels of unemployment continue and wage stagnation remains, the number of hungry and food-insecure families will either stay the same or rise. So, too, will America’s hunger bill.

What remains unchanged from our original research in 2007 is the most salient point: “The nation pays far more by letting hunger exist than it would if our leaders took steps to eliminate it.”

Adapted from Hunger in America: Suffering We All Pay For, a 2011 report by the Center for American Progress.