The failures of trust and acknowledgment around which remarriage comedies revolve are acts of violence. As Cavell puts it in Cavell on Film: “In our slights of one another, in an unexpressed or disguised meanness of thought, in a hardness of glance, a willful misconstrual, a shading of loyalty, a dismissal of intention, a casual indiscriminateness of praise or blame—in any of the countless signs of skepticism with respect to the reality, the separateness, of another—we run the risk of suffering, or dealing, little deaths every day” (340).

In comedies of remarriage the outcome of a failed marriage is divorce. In Hitchcock thrillers the worst case scenario is murder. Divorced couples can remarry, but murder—divorce Hitchcock style—is final. To transform their marriage into a relationship worth having, Lina (Joan Fontaine) and Johnnie (Cary Grant) in Suspicion, like the couples in remarriage comedies, have to overcome their failure to trust each other. But Lina also has to overcome a formidable obstacle, internal to her relationship with Johnnie, that the heroines of those comedies do not have to face—the all-consuming suspicion, which mounts throughout the film, that Johnnie is literally a murderer.

In North by Northwest Eve explains to Roger how she came to fall in with a murderer. She says that when she first met Phillip Vandamm she “saw only his charm.” Vandamm is played by James Mason, so that charm is world-class. But Robert Donat in The 39 Steps, like Grant, is no less charming. Henry Kendall and Leslie Banks play characters, in Rich and Strange and The Man Who Knew Too Much respectively, who are so charmless they appear self-evidently “what they seem,” to borrow a phrase from the villainous Professor Jordan. (Both are so wooden that if Hitchcock had wanted them to give off sparks, he would only have had to rub them together.)

But Hannay is such a smooth talker, so adept at what the Cary Grant character in North by Northwest calls “expedient exaggeration,” that it is almost imaginable that Hannay is the murderer Scotland Yard believes him to be, the murderer he jokingly pretends to be when he and Pamela, posing as a runaway couple, have no choice but to share a bed. Not that Pamela ever takes this possibility seriously enough to find herself actually imagining that he might murder her. When she half-jokingly calls him a “big bully,” it is clear that she isn’t afraid of him and never really was. What makes Hannay worthy of Pamela, what would have made Robert Donat as fit as Cary Grant to play the male lead in a Hollywood comedy of remarriage, cannot be separated from what it is about Hannay that makes Pamela more than willing to perform the leap of faith it takes for her to trust him.

If it is a defining feature of Hitchcock thrillers that their world contains a murderous villain who is a stand-in for the film’s author, it is also a feature characteristic of Hitchcock thrillers—again, with exceptions that prove the rule—that before their protagonists can achieve a relationship worth having, they must prove themselves not to be guilty of murder. From “little deaths” rebirth is possible. Those who inflict “little deaths” can, in principle, be forgiven. But if Hannay were literally to murder Pamela, as at one point he pretends he might do, that act would literally be unforgivable. A murderer’s victim is in no condition to forgive the murderer. Nor does any living person have the standing to forgive the murderer on the victim’s behalf. (Suspicion’s previewed ending, in which Lina, believing Johnnie has poisoned her, forgives him for murdering her, is an exception that proves this rule.)

For the victim, murder terminates the cycles of death and rebirth that make it possible, in Emerson’s view, for human beings to walk in the direction of the unattained but attainable self. Churchgoing Catholic that he was, Hitchcock may have believed that God can absolve even this mortal sin. But even though in his capacity as author Hitchcock wields a godlike power to punish or reward his films’ characters, he does not have the power to grant absolution to murderers—even murderers who exist only in the worlds of the films he authors. In I Confess (1953) Father Logan, in his capacity as a Catholic priest, receives a murderer’s confession. But even if the actor who plays him had been a priest in “real life,” as Montgomery Clift most certainly was not, the character he plays would not have the powers and authority that, in Catholicism, can be conferred only by the Church, which claims an apostolic succession that it traces back to Jesus, thus to God. In his role as author, Hitchcock casts himself as God, in effect, but—thank God!—that does not make him God. Within the world of a Hitchcock film—a world authored by a merely human artist, not by God (if there is a God)—no one—no individual, no institution—has the authority or power to act in God’s name.

Within the world of a Hitchcock thriller, then, murder can never be absolved. Murder permanently fixes the identity of the murderer. Murderers are condemned never to become other than the murderers they are. By irrevocably denying another person the freedom to be reborn that, in Emerson’s view, is a defining feature of being human, murderers forfeit their own freedom to change, hence their own humanity. If “each man kills the thing he loves,” are we all murderers? Are we all condemned?

It is no wonder that Hitchcock thrillers, in which the protagonist’s quest for selfhood often requires proving that she or he is not a murderer, raise age-old questions of moral philosophy. What, if anything, legitimizes taking the life of another human being? What, if anything, makes killing anything other than murder? How, if at all, does the act of killing change the person who performs that act? From the lodger, who is ready to kill the Avenger should he catch up with him, to Richard Blaney in Frenzy, who is kept from becoming a murderer only because it is a woman Bob Rusk has already murdered, not Rusk himself, whose body is hidden under those bedclothes, every Hitchcock thriller addresses such questions and meditates on their implications for the art of pure cinema as Hitchcock understood and practiced it.

For Hitchcock, the imperative of defeating the Nazis gave these questions about the morality of killing special urgency in the late 1930s and early 1940s, the way the imperative of abolishing slavery gave them special urgency for Emerson in the years leading to the Civil War (when he and Thoreau, apostles of nonviolence, found themselves defending John Brown’s controversial and violent raid on Harper’s Ferry). To defeat the Nazis, the Allies had to find it within themselves to kill. But if by killing we deny the humanity of our enemies, what, if anything, makes us superior, morally, to Nazis? Does killing murderers make us murderers?

In Secret Agent, made in 1936 but set during World War I, Richard Ashenden (John Gielgud)—a writer the British government falsely reports killed in order to employ him as a spy—watches through a telescope as the General (Peter Lorre), his sociopathic but strangely likable hit man associate, readies to kill the elderly man they believe to be the spy it is their mission to assassinate. Richard cries out, “Watch out, for God’s sake!” But this is too little, too late, to stop the General from pushing the man over a cliff.

In the meantime Elsa (Madeleine Carroll), a newly hired agent whose assignment is to pretend to be Mrs. Ashenden, is having tea with the old man’s wife. When she began her job, Elsa expected to find killing in real life even more thrilling than in books. But the sight of the man’s cocker spaniel, inconsolable as if already mourning the master fated never to return, awakens Elsa to the true dimension of killing.

When he discovers that the General had mistakenly killed an innocent man, Richard muses bitterly to Elsa, “I was there, all right. A half-mile away, at the other end of a telescope. Just one of those long-range assassins. That doesn’t make it any better, does it?” And does it “make it any better” that we watch the killing on film, from a place outside the projected world? Are we “long-range assassins,” too? Is Hitchcock, watching from a place on the other side of the camera?

“I don’t like murderers,” Elsa says. “Can’t we give it all up?” Richard responds. “Would that make any difference—to us?” Nodding, she kisses him, wordlessly imposing it as a condition of their continued relationship that they both give up their jobs and vow never again to be party to killing. Richard agrees, but later he insists on following a clue he hopes will lead him to the real spy so that this time the “right” man can be killed. True to her principles, Elsa walks out on Richard. She goes off with Robert (Robert Young), an American waiting in the wings. But then Richard discovers that Robert is the spy.

On a train passing through enemy territory, Richard and the General catch up with Elsa and Robert. Richard is about to kill Robert, but Elsa pulls a gun on Richard, saying, “I’d rather see you dead than do this.” She is threatening to kill the man she loves to keep him from killing a spy, even though letting that spy live would likely cost thousands of British lives. By utilitarian standards, Richard would be doing a good thing by killing Robert, since stopping thousands of people from dying promises the greater good for the greater number than letting one man live. But Elsa isn’t thinking like a utilitarian. To her way of thinking, it would be an act of murder for Richard to kill Robert, no matter how desirable the consequences. By Kantian standards, the fact that thousands would otherwise die is irrelevant, morally speaking; killing another human being is always a violation of the Moral Law. For Kant it would be no less morally wrong, no less forbidden, for Elsa to kill Richard in order to keep him from killing, than for Richard to kill Robert. But Elsa isn’t thinking like a Kantian, either. She is thinking like an Emersonian perfectionist. She would kill Richard to keep him from performing an act that in her eyes would make him a murderer, and thus would forever keep him from changing, keep him from becoming, keep him from walking in the direction of his unattained but attainable self.

Elsa doesn’t like murderers. She doesn’t want to be the kind of person who would let the man she loves become a murderer. Of course, she no more wishes to kill Richard than she wishes for him to kill Robert. She hopes that her threat, or vow, will provoke Richard to open his eyes to the true dimension of killing and thus keep both of these killings from happening. But if she does have to kill Richard—if she believes that killing Richard is a step she must take to continue walking in the direction of the unattained but attainable self—this act of killing would not, in her own eyes, be murder.

At this intractable impasse, Hitchcock makes an executive decision that renders these questions moot. Hearing bombers overhead, the General says, in Peter Lorre’s inimitable manner, “Accidents. Most convenient coincidences.” Rolling his eyes not so much heavenward as cameraward, he adds, “Heaven is always with a good cause.” “I think we can forgo the Thanksgiving service,” Robert quips just before a heaven-sent—or, rather, Hitchcock-sent—bomb derails the train, pinning the American in the wreckage. Richard reaches out to strangle Robert but finds he cannot bring himself to perform the act that would make him a murderer in his own eyes, not only in Elsa’s.

The General, who enjoys killing, doesn’t think in moral terms at all. He picks up the gun and is more than willing to kill Robert. First, however, he puts down the weapon to light a cigarette for his intended victim, toward whom he feels no animosity. Although already mortally injured, Robert picks up the gun and gratuitously shoots the General to death. Utterly indifferent to this man’s fate, Robert dies. But Robert’s blood is on the hands of no one but the film’s author, the “long-range assassin” who arranged for the bomb to drop. It is the film’s author who kills Robert. In Hitchcock’s eyes, is this murder? Does it make Hitchcock a murderer? And do these questions even make sense, given that this is a movie, not reality, hence that when Robert is killed, no one really dies?

Secret Agent ends with the Home Office receiving a postcard with the handwritten message “Never again” and signed “Mr. and Mrs. Ashenden,” with the beaming couple, their sham marriage now transformed into a legal one, superimposed over the postcard. Evidently, Richard and Elsa are now walking together in the direction of their unattained but attainable selves. But to achieve a relationship worthy of a comedy of remarriage, they have found it necessary to repudiate the world of the Hitchcock thriller, a world that revolves around murder. “Never again,” they’ve written on the postcard. They have exited that world, vowing never to return.

Not so Hitchcock.

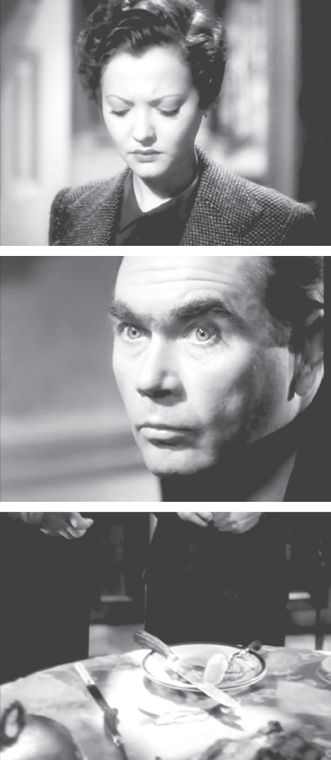

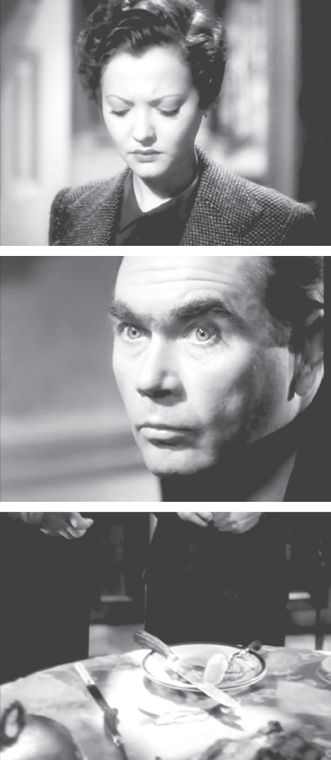

Sabotage, too, revolves around murder, but it gives Secret Agent a dialectical twist in the sequence in which Mrs. Verloc (Sylvia Sydney), with our approval and Hitchcock’s, stabs to death her husband (Oscar Homolka). Once he reaches for the knife, the die is cast, and she has no choice but to grab it first and stab him with it. Otherwise, he will kill her. We know this because Hitchcock’s camera makes sure that we notice that her husband notices the way she looks at the knife just before picking it up.

The thought of killing first enters her mind, then jumps to his. And it enters her mind because she wishes for him to die. She wishes for him to die not simply because he made her little brother carry the bomb whose untimely explosion claimed his life. She wishes for him to die because his words and actions betray his utter indifference to the boy’s death. All he wanted to talk about, when he sat down to dinner, was how he likes his cabbage to be cooked. So now his goose is cooked. His utter lack of regard for human frailty makes him so loathsome in his wife’s eyes that she no longer sees him as a person. This frees her to pass judgment on him without violating the Emersonian principle that “the time to make up your mind about people is never.” It also frees her to kill him without believing that this makes her a murderer. She does not want to be the kind of person who would let such a monster live.

Nonetheless, we do not know whether Mrs. Verloc would actually have killed her husband were it not for her recognition of his recognition of the way she looks at the knife. Hitchcock cuts to a shot of the knife a moment before she looks at it. The camera’s gesture thus appears to cue, rather than simply register, her glance.

Does this shot then register her thought, not her action? But it is also as if by this cut Hitchcock calls the knife to her attention—as he calls it to our attention—and by this means provokes her to think of killing her husband. In Hitchcock’s films the camera often seems to call forth a character’s thought—to plant a thought in the character’s mind, or to awaken a thought already there, below the threshold of consciousness.

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.2

As in Secret Agent, the film’s author—that “long-range assassin,” Hitchcock—makes a killing happen. In Sabotage Hitchcock intervenes, this time more subtly, by using the camera not to follow but to lead the exchange of glances that provokes Verloc to reach for the knife, giving his wife no choice but to grab it first. Hitchcock’s intervention allows her to kill her husband, as she had wished to do, but to kill him in self-defense, thus without committing what the law deems to be the crime of murder. (Whether she really kills him to keep him from killing her or [also?] to satisfy her wish for him to die is a question that only God—not even Mrs. Verloc herself, and not even Hitchcock—has the ability to answer.)

Nonetheless, like young Charlie (Teresa Wright) at the end of Shadow of a Doubt, or Eve (Jane Wyman) at the end of Stage Fright, Mrs. Verloc is saddened and chastened. She is saddened by her brother’s death and by the knowledge that there exist in the world monsters like her husband, human beings who forfeit their humanity by having no regard for the humanity of others. She is chastened by the knowledge that in repudiating her husband’s inhumanity, she found within herself the willingness, and the ability, to kill.

Hitchcock no more condemns Mrs. Verloc for thinking that she can kill her husband without becoming a murderer than he condemns Elsa for thinking that it would be murder for Richard to kill Robert. Both women think like Emersonian perfectionists, and Hitchcock respects them for this. In both films, however, he intervenes.

In Secret Agent Hitchcock’s intervention frees Elsa from the need to kill, thus leaving it a pointedly unanswered question whether killing another human being is ever anything but murder. In Sabotage Hitchcock intervenes to force Mrs. Verloc’s hand, to make her do what she wishes to do (what Hitchcock wishes her to do, what we wish her to do). His intervention leaves her no choice but to kill, at least if she values her own life.