Of Hitchcock’s postwar films of the 1940s, Rope most fully articulates the issues concerning killing and murder that are addressed in Lifeboat and Notorious. When Rupert (James Stewart) opens the chest holding David’s body, Brandon (John Dall), one of the young murderers, tells his former teacher that “Phillip and I have lived what you and I have talked.” What they had “talked” involved Rupert’s theory that “the lives of inferior beings are unimportant” and thus that “moral concepts of good and evil and right and wrong don’t hold for the intellectually superior.”

Rupert responds passionately: “You’ve thrown my own words right back in my face, Brandon. You were right to. If nothing else, a man should stand by his words. But you’ve given my words a meaning that I’ve never dreamed of. And you’ve tried to twist them into a cold, logical excuse for your ugly murder.”

When in Strangers on a Train, Guy (Farley Granger) shouts that he could kill his scheming wife, and when he earlier patronized Bruno (Robert Walker) on the train by glibly agreeing with him about the desirability of each performing the other’s murder, but without dreaming (or so it would seem) that Bruno would carry out his side of the bargain, Guy fails to live up to Rupert’s principle that “a man should stand by his words.” Is Guy’s failure the moral equivalent of murder?

When Rupert insists that by twisting his words into an excuse for an “ugly murder”—are all murders, even artistically perfect ones, “ugly”?—Brandon has given them a meaning he had “never dreamed of,” he conspicuously fails to say what he did mean by his words, how he could have meant by them anything other than the meaning Brandon drew from them. Unable to defend his words, ashamed at having spoken them, Rupert is reduced to saying to Brandon that “there must have been something deep inside you from the very start that let you do this thing” and “something deep inside me that would never let me do it and would never let me be a party to it now.” Rupert is not saying that Brandon forfeited his humanity by murdering David. He is saying that because of the mysterious “something” Brandon was born with “deep inside,” he was never really human in the first place.

Surely Hitchcock is aware that Rupert is thinking like a Nazi when he claims to be superior to Brandon (even if he is claiming to be superior morally, not intellectually or physically). Hitchcock is not endorsing Rupert’s view that ordinary Americans and murderers are born with different hidden “somethings.” Even if Willi, say, has a “something” that allows him to kill Gus, the lack of that “something” doesn’t stop the Americans from killing Willi. And, as we will see, Rupert, too, is capable of killing. Before he takes action, though, Rupert delivers an eloquent speech that articulates principles that up to a point Hitchcock—and we—can readily endorse:

Tonight you’ve made me ashamed of every concept I ever had of superior or inferior beings. But I thank you for that shame. Because now I know that we’re each of us a separate human being, Brandon, with the right to live and work and think as individuals but with an obligation to the society we live in. By what right do you dare say that there is a superior few to which you belong? By what right did you dare decide that that boy in there was inferior, and therefore could be killed? Did you think you were God, Brandon?…I don’t know what you thought or what you are, but I know what you’ve done. You’ve murdered!

When Rupert moves closer to the window, Brandon nervously asks him what he is doing. Rupert’s answer makes clear his intent to “stand by his words” this time, to transform “talking” into “living.” “It’s not what I’m going to do, Brandon, it’s what society is going to do. I don’t know what that will be, but I can guess. And I can help. You’re going to die, Brandon.” It is only to give society the chance to do whatever it decides to do, Rupert claims, that he now fires three shots through the open window. The shots provoke neighbors and passersby to gather, discuss the situation and call the police, setting in motion the machinery of justice by which society will decide what to do about the two murderers. And yet Rupert knows—or thinks he knows—that by firing these shots, he is causing Brandon to die, the way Devlin knows he is causing Sebastian to die when he locks him out of the car. Indeed, it is with undisguised glee that Rupert repeats, before firing the shots, “You’re going to die!” He is not merely “guessing” that this is the sentence society will decide to impose; he is taking it on himself to pass judgment. It is clear from his tone that it pleases him to be condemning Brandon to death. He wishes for Brandon to die, the way Mrs. Verloc wishes for her husband to die, the way the others wish for Willi to die, the way Devlin wishes for Sebastian to die.

When Rupert insists that he “never dreamed” that Brandon would transform his teacher’s words from “talking” to “living,” it is possible, of course, that he is simply lying. But even if he is not lying, he is not necessarily speaking the truth. It is a fact about being human, after all, that we do not always remember our dreams, as we are not always conscious of our intentions. And Rupert may have a motive as well as a reason for wishing to deny his own guilt (a motive he has in common with Vertigo’s Scottie, that other James Stewart character). Rupert wishes for Brandon to die for being utterly indifferent to the humanity of others. But perhaps Rupert also wishes this because he is unwilling, or unable, to face his unbearable sense of guilt for the consequences of his own words. If Rupert were simply to shoot him to death, he could not continue to believe in his own superiority to Brandon. But what if society were to take it upon itself to condemn Brandon to death? What I am suggesting, perhaps too obscurely, is that it is possible to view Rupert as twisting his own words, as Brandon had done, into a justification for his own “ugly murder.” That is, it is possible to view Rupert’s firing of the shots as a way of provoking society to perform “his” murder (the way Bruno performs Guy’s murder in Strangers on a Train). To throw Rupert’s words back at him: By what right does he “dare decide” that this “separate human being” must die? For that matter, what, if anything, gives “society” such a right?

Hitchcock films Rupert’s speech in a singular way that underscores its ambiguity. On the words “we’re each of us a separate human being,” the camera begins to twist counterclockwise. The camera’s turning meshes with Rupert’s movement so that on his words “think as individuals” he is looking toward the camera. In eminently Hitchcockian fashion these movements cause Brandon, who looks perplexed by Rupert’s words, to eclipse him in the frame.

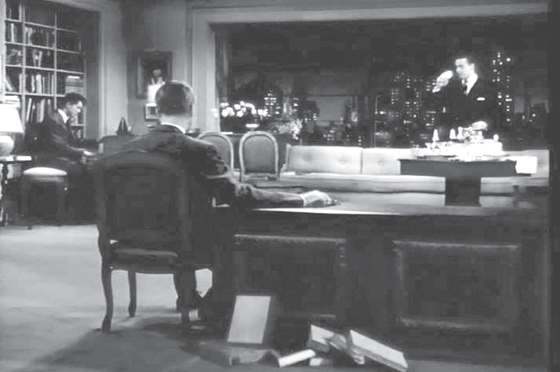

Figure 8.1

As Rupert continues speaking, the camera reverses direction and starts twisting clockwise. Again, the camera’s movement meshes with Rupert’s to cause his figure to be eclipsed. Then the camera reverses direction again, and yet again, causing this eclipsing to occur two more times. Finally, the camera moves in until it isolates Rupert’s arm, hand, and gun, framed by the window. He pulls the trigger and three shots go off.

It is impossible to view this passage without being cognizant of the role the camera plays both in its design and its execution. At least in part, it was to impress and please him, Rupert intuits, that Brandon conceived the plan to murder David and manipulated Phillip to carry it out the way he did. What goes without saying in the film is that Hitchcock made Rope the way he did—with complexly choreographed ten-minute shot sequences unbroken by edits—to impress and please us. Like Brandon, Hitchcock wished for somebody else to know how brilliant he is. Indeed, with the possible exception of Psycho, no Hitchcock thriller is more overt in asserting a metaphorical equivalence between Hitchcock’s art in creating the film and the act of murder around which the film’s narrative revolves.

No matter how compellingly Rope affirms Rupert’s rebuke of Brandon’s inhuman indifference, the film calls Rupert’s moral authority into question as well. It also identifies its author’s act of artistic creation with Brandon’s attempt to perform the perfect murder. Thus it calls Hitchcock’s own moral authority into question. It is this instability of identification, this oscillation between repudiating murder and enjoying its fruits, that the camera’s gestures in this passage—and in Rope as a whole—so brilliantly convey. By designing Rope to declare his own wish for “somebody else to know how brilliant he is,” Hitchcock places himself in Brandon’s position and the viewer in Rupert’s. But by designing this film (like Shadow of a Doubt before it, as I argue in The Murderous Gaze) to teach us how to view a Hitchcock thriller in a way that acknowledges its author’s brilliance, Rope also places Hitchcock in Rupert’s position and the viewer in Brandon’s.

Figure 8.2

As the camera now pulls back, we hear the voices of neighbors and passersby; collectively, they represent society. The camera continues pulling back to a tableau. Rupert is in the foreground, his back to the camera; Phillip, in the left background, begins to play the piano; and Brandon, in the right background, pours himself a drink and, with the sangfroid of the Ray Milland character at the end of Dial “M” for Murder, raises his glass, like a sportsman toasting his opponent’s victory in what had been only a well-played game.

Hitchcock allows this framing, and the meditative mood it casts, to linger as the piano music mingles with the crescendo of a police car siren as the final credits roll. Until the police arrive, there is nothing for Rupert to do but reflect on the events that have transpired and the disturbingly ambiguous role he has played in them. This is a moment of meditation for Hitchcock, too. And for us.