Vera Miles again has an enigmatic expression at the end of The Wrong Man, when Manny, Rose’s husband (Henry Fonda), visits her in the mental institution to which she asked him to commit her after her breakdown, to tell her that their ordeal is over—he was on trial for a series of holdups the law-abiding Manny did not commit—because his case was dismissed after the police caught the real criminal. Rose repeats, flatly but perhaps not without hostility, “That’s fine for you,” before withdrawing into an impenetrable silence.

These words pierce Manny’s heart, and Rose seems to mean for them to, as if they are her revenge. For what? What “little deaths” could this all but saintly man, who always tries to do right by his family, have inflicted on his wife, whether in reality or in her imagination? Manny is not violent like Carl. Nor does he lack regard for human frailty, like Willi, Rupert, or Callew. But there are ways of failing to acknowledge other human beings without beating them or holding their humanity in contempt. After Uncle Charlie announces that he will be leaving Santa Rosa in the morning, Emma (the great Patricia Collinge), Young Charlie’s mother and Uncle Charlie’s sister, breaks down. Her beloved brother’s stay in her home had reminded her that she should not be treated simply as a satellite of her husband. Before her voice trails off into melancholy silence, she says quietly, to no one in particular, “You know how it is. You’re your husband’s wife…”

Figure 10.1

Manny is selfless to a fault, but he has been oblivious, as even good men can unthinkingly be, of his wife’s right to feel that she is a person in her own right. For Manny the two children come first, his mother second, Rose third. And since his arrest he became so absorbed in his trial that it hadn’t occurred to him that Rose could be undergoing a trial of her own. He hadn’t even noticed that she was descending into madness until his lawyer called it to his attention. Is it madness for Rose to blame Manny for her madness?

In Notorious, as we have seen, Alicia experiences an epiphany at the racetrack. She awakens to the ways her own actions and failures to act, her own words and silences, as surely as Devlin’s, are implicated in leading them to their present impasse. But she does not awaken to her real condition as a denizen of the world projected on the movie screen. She remains blind to the reality that her life is scripted, that we are viewing her now, that at this moment she finds herself at the border that separates our world from her world. To that reality Rose, too, once was blind, but there is a remarkable moment when she seems to see, or at least glimpse, what Alicia does not see. I am thinking of the moment when Rose, learning of the death of a man they were counting on as a witness who could verify her husband’s alibi, bursts into hysterical laughter and says to Manny, who is stoically prepared to keep soldiering on, “Don’t you get it?” She goes on to explain to her uncomprehending husband that he cannot win because “they” have stacked the deck against him.

This moment foreshadows Rose’s madness. It also reveals an extraordinary power she possesses—a power I think of as clairvoyance. Rose’s clairvoyance reflects Hitchcock’s understanding of who Vera Miles was capable of being, or becoming, within the world of a film. He envisioned her as projecting a distinctive otherworldly quality, a quality he was seeking in an actress at this moment in his career when his films were becoming more openly—and more profoundly—metaphysical. After The Wrong Man Hitchcock wanted Vera Miles to star in Vertigo, but her pregnancy made that impossible. The fact that Kim Novak would be utterly miscast as Elsa or as Rose underscores how different Vertigo would have been had the otherworldly Vera Miles, not the carnal Kim Novak, been the object of Scottie’s obsession. Would Vera Miles have been better than Kim Novak in Vertigo? No one could be. But in the very different Vertigo that might have been, no one could have been better than Vera Miles.

That Manny is utterly oblivious of the dark reality Rose is capable of glimpsing is part of the point of another of The Wrong Man’s most remarkable passages. Having been arrested late one night as he was returning home from his job as a bass player in the Stork Club band, Manny finds himself alone in a prison cell. A series of point-of-view and reaction shots makes all too clear that the cell is devoid of anything meaningful for him to rest his eyes on. Manny looks down at his hands, and Hitchcock cuts to a close-up that isolates them in the frame. As if they have a will of their own, they slowly tighten into fists—Manny’s only physical gesture in the entire film that expresses the impulse to physical violence, an impulse that is only natural for a victim of injustice to feel but which Manny almost obsessively represses. Then, as if exhausted, he leans against the wall and looks in the direction of the camera.

In fiction films it is a familiar strategy for conveying that a character is turned inward to have that character look toward the camera without seeming to see it. We understand that when Manny, wrongfully imprisoned, alone with his nightmarish thoughts, stares into the middle distance, he is looking at nothing. Rather, his looking toward the camera conveys that he is absorbed by what he is thinking or imagining. To convey this, Henry Fonda has to act in a way that denies the reality of the camera in his presence. But Manny, the character the actor is playing, has no need to deny reality in order to act as if no camera were in his presence. In Fonda’s world the camera is a presence—a presence that is also an absence, insofar as the views it is capturing are destined to be projected onto movie screens in the future so as to enable the likes of us, who are not in his presence, to view him. In Manny’s world, by contrast, the camera is an absence. But it is an absence that is also a presence, insofar as the lens the actor is looking at is in effect transformed, within the character’s world, into an imaginary screen on which what we might call his “inner reality” is projected. In Manny’s world the camera’s gaze becomes only a projection of his imagination, but it is no less real for that; it is no less real—and no less unreal—than his inner reality itself.

Figure 10.2

As if to shut out reality altogether, Manny now closes his eyes. At this very moment, the camera begins turning; not pivoting on its axis—it never stops facing Manny—but circling in space as if it were fixed to the side of a revolving wheel. The camera’s circling causes our view of the projected world—and Manny within it—to circle. As the movement accelerates, so does the quietly rhythmic, repetitive, melody-less, almost Philip Glass-like music—dominated by Manny’s own instrument, the double bass—that Bernard Herrmann composed for this passage. Soon, we can no longer tell—could we ever?—whether it is Manny’s world that is circling while the position from which we are viewing it remains stationary; whether it is our position that is moving, while Manny’s world remains in place; or both. This also means that we can no longer tell, as if we ever could, whether it is from a position inside Manny’s world, or outside his world, that we are viewing him.

Figure 10.3

Self-evidently, no frame enlargement can convey the mood the camera captures, and casts, in this shot. Visually, this is anything but a moment of stasis, anything but a timeless moment. Indeed, the camera’s gesture here precisely acknowledges, or declares, the transience that is one aspect of the temporality of film: the fact that we experience every film moment—as we experience every moment of our lives—within time, the suspense-inducing fact that, for us as well as for the characters, time moves on like clockwork—and that time is running out.

This passage perfectly exemplifies Hitchcock’s understanding that the camera is more than a machine that passively takes in whatever happens in front of it. The camera also has the power to make things happen. Within our reality, and within Manny’s reality as well, the camera—that is, what the camera becomes within the film’s world—is at this moment making the projected world turn, not to mention our stomachs. The dizziness this turning causes us to suffer engenders the uncanny impression that Manny would find relief from his vertigo, as we would, if only the camera would stop moving. It also engenders the uncanny impression that Manny has the power to make his world, the projected world, stop spinning—as if all it would take would be for him to open his eyes, to awaken to reality. This he is unwilling, or unable, to do.

Later in the film, Rose, in her madness that is also clairvoyance, provokes Manny to open his eyes, if only for a moment, to glimpse the uncanny reality that, as we might put it, the reality of his world is that it is not reality. This is the climax of one of the most profound—and disturbing—sequences in this or any Hitchcock film, a sequence that reverberates deeply within Psycho, The Birds, and Marnie.

Aware now that his wife is disturbed, Manny again comes home from work late at night and finds that Rose hasn’t gone to bed. Solicitously, he says, “You should have been asleep a long time ago.” “I can’t sleep,” she replies. This initiates a tense exchange that is presented, in characteristic Hitchcock fashion, by alternating between two camera setups. In “her” shots, Rose shares the frame—for Hitchcock, this, too, is a characteristic practice—with two symbolically charged objects: a large table lamp and their still-made double bed.

MANNY: Rose, this is the second night I’ve come home and found you awake. And you’re not eating either. Honey, this isn’t right. Don’t you think you ought to see a doctor?

ROSE: There’s nothing wrong with me. Why should I see a doctor?

MANNY: Well, when a person doesn’t sleep and doesn’t eat, and seems to lose interest in everything, maybe a doctor can think of something.

ROSE: We can’t pay for things now. How could we pay for a doctor?

MANNY: I’ve been thinking about the trial, and who’ll stay with the boys while we’re away. I’ve called Mother and she’ll come over and stay.

ROSE: If you want her to.

Clearly, Manny begins their conversation with an agenda, but he doesn’t want Rose to know this. Clearly, too, Rose sees right through him. He doesn’t want her to know the real reason he thinks she needs a doctor. Surely she understands, though, that it’s because he thinks she’s crazy. When she points out that they can’t afford to pay for a doctor, we recognize this as a thinly veiled accusation. In the course of this conversation Rose will come to reveal—and perhaps discover for herself—how bitterly she resents Manny—and for good reason—for having repeatedly borrowed money and paid for things on time even though she told him not to. Indeed, if he had listened to her, he wouldn’t have gone to the insurance company office to borrow money and would never have been arrested.

Figure 10.4

Furthermore, when Rose responds to Manny’s statement that his mother will come over to stay with the boys by saying “If you want her to,” the palpable hostility in her voice bespeaks what we may surmise to be a long-standing resentment of Manny’s mother for playing too intrusive a role in her son’s relationship with his wife, and of Manny for letting his mother do so. As will momentarily become explicit, she also intuits that his real intention is to get the boys out of the house to protect them from their crazy mother.

Realizing that the conversation isn’t going as he had planned, but perhaps not quite fully picking up on Rose’s veiled and not so veiled accusations, Manny, saying only “Rose…,” cautiously moves closer to her. The camera, moving to follow his movement, reframes to a two-shot. Rose’s pointed silence cues a cut to a new setup, then to its reversal, and Hitchcock now begins alternating these setups. Thus begins a new phase of this shot/reverse shot dialogue sequence, which so clearly was to serve Hitchcock as a model for shooting and editing the elaborate conversation between Marion and Norman in the Bates Motel parlor.

In an altered, more intimate, voice that reflects his closer physical proximity to his wife, Manny says, “The last few days, you haven’t seemed to care what happens to me at the trial.” As he speaks these words, Rose stares at him with an intense, scrutinizing gaze. I cannot imagine that it escapes her notice that his caring, solicitous tone is belied by his choice of words, their implication that what really concerns him is not what is happening to her, so much as her seeming lack of regard for what might happen to him.

No doubt, Manny expects Rose to respond by saying that she really does care how his trial is going. Heartbreakingly, she says instead, “Don’t you see? It doesn’t do any good to care.” Rose is acknowledging, not denying, that she has stopped caring what happens to Manny at the trial, but her tone, too, is now solicitous, not angry or bitter. She recognizes that he simply does not see what she sees so clearly. She is certain that their future has already been scripted—which is true—and that, as she puts it, “No matter what you do, they’ve got it fixed so that it goes against you; no matter how innocent you are or how hard you try, they’ll find you guilty”—which is, by contrast, a belief that seems, on the face of it, to be nothing but a paranoid fantasy, a symptom of her madness. In the end, after all, her prophecy will not come true. The case against Manny will be dismissed.

Rose sounds crazier and crazier—she also begins to sound as if she’s living in the world of The Birds, not the world of The Wrong Man—as she goes on: “Well, we’re not going to play into their hands. You’re not going out. You’re not going to the club and the boys aren’t going to school. I’ve thought it all over sitting here. We’re going to lock the doors and stay in the house. We’ll lock them out and keep them out.”

Figure 10.5

“Yes, that’s the thing to do,” Manny says in a voice even calmer than usual, not daring to confront her. But when he adds, pretending it’s an afterthought, “There’s one thing we must arrange, whether Mother comes here or the boys go and stay with her,” he is clearly unaware how easily Rose sees through him. After a long pause, she rises, so that she is a looming figure in the frame as she says to him, forcefully, “You want to get them out of the house because you think I’m crazy, don’t you?” Vehemently, she repeats the words, “Don’t you?” She all but spits those words out. “Well you’re not so perfect either. How do I know that you’re not crazy? You don’t tell me everything you do. How do I know you’re not guilty? You could be. You could be!”

Saying “Rose” in a gentle voice, Manny, too, gets up. As the camera follows his movement, causing Rose to be excluded from the frame, Manny walks past two paintings and a mirror on the wall to the bedroom door and closes it. I take it that it is clear to Rose, as it is to us, that Manny wants to keep their young sons from hearing their mother sounding like this.

I don’t imagine that Rose, even in her madness, actually believes that Manny may have committed the crimes for which he is on trial. But that doesn’t mean she sees him as guiltless. Nor does it mean that he isn’t crazy. The camera is on Rose as she goes on: “You went to the loan company to borrow money for a vacation. You did that when we couldn’t afford it. You always want to buy things on time. I told you not to. I told you they’d pile up and pile up and we couldn’t meet it all.”

This is a serious charge Rose is leveling against Manny, and a devastating one. To be sure, it isn’t fair for her to imply that because he visited the loan office, it’s his fault that he was arrested. But it is fair for her to point out that it was crazy for him to keep borrowing money without having a plan for paying it back. And it is fair for her to charge Manny, no matter how well-intentioned he may be, with failing to listen to her, failing to take her ideas seriously—fair for her to charge that she is only her husband’s wife to him, not a person in her own right.

“Rose,” Manny again says gently, recognizing how upset she is, but not acknowledging the truth of what, in her disturbed state, she sees so lucidly. There is reason in her madness, in other words. There’s also madness. Goaded, not relieved, by his attempt to calm her, she becomes unhinged. “And it did pile up,” she shouts hysterically. “Honey,” he interjects, again trying to calm her. But she’s beyond calming. “And then they reached in from the outside! And they put this last thing on us!” She is shouting loudly now. “And it’ll beat us! And you can’t win!”

At this climax of Rose’s explosion of fear and anger, Manny reaches his hand out to her shoulder. Recoiling with a loud intake of breath, she stares at his hand, as he had stared at it himself in his prison cell, evidently fearing its potential for violence. We hear the sound of an elevated subway train that passes close to their home—at once credible as a “real” sound, and an expressive objective correlative to her inner turmoil. The camera moves with her as she steps back from Manny, significantly leaving only his hands, doubled by their shadows, in the frame with her. The train sound grows louder and more agitating, and the camera moves in on Rose as she shouts, “They spoiled your alibi!” As she backs away further from Manny, the camera pulls in on Rose, removing him altogether from the frame. Rose’s shadow eclipses one picture on the wall, but not a portrait of Jesus that is in the background of this frame, as she shouts even more loudly, “They’ll smash us down!”

Figure 10.6

There is a cut to Manny, doubled by his shadow. He moves toward Rose, hence toward the camera. His motion cues a cut to her, backing away from him in fright. Clearly, she has suddenly stopped believing that “they” are out to smash them both. At this moment she sees Manny as the embodiment of “them.” She looks down again, and there is a cut to her own hand, not his this time, as it picks up a hairbrush and swiftly pulls it up and out of the frame; a quick cut to Rose with arm and hairbrush raised; to arm and brush, framed from below; to Manny, watching wide-eyed; to the brush, slashing through the frame from top to bottom; and finally to a close-up of Manny, his eyes now tightly shut (as they were in his prison cell when the camera made the whole world, with Manny in it, begin to circle). When the hairbrush swiftly enters this frame and brutally hits Manny’s left temple with an exaggeratedly loud, sickening thud, the effect is shockingly violent. Only then does he open his eyes and there is a cut, coinciding with a sound of breaking glass and a quite inexplicable but expressive sound as of tearing canvas, to a shot in which Manny is staring wide-eyed directly at the camera, a jagged fissure running the height of the frame and splitting his face into two ill-fitting pieces, one eye higher than the other.

What are we seeing in this remarkable shot? Are we seeing Manny staring at his own image in the cracked mirror we just heard breaking? Or is this a point-of-view shot that represents Manny’s reflection, as he is seeing it in the mirror? Manny viewed and Manny viewing fuse with the camera’s view to create an image—and self-image—of his shocked, split, transfixed face. Manny is shocked that his gentle, compliant, uncomplaining wife has such violence within her. If he didn’t know this about his wife, he doesn’t really know her. But it’s Manny’s own fractured image, not Rose’s, that this shot shocks us by capturing, and expressing. There is something about himself that Manny is shocked to discover he doesn’t know. He doesn’t know what he has done, what he is, that makes it possible for Rose to see him as so hateful, and so terrifying, that she can believe he wants to “smash her down,” and makes her wish to kill him.

In the shower murder sequence of Psycho, Hitchcock contrives to identify the shower curtain that Marion’s killer tears open with the movie screen, as if the murderer also tears open the “safety curtain” that keeps us safe from murderers who dwell within the world on film, so that it is as if we, too, find ourselves face-to-face with our own murderer. I take this shot in The Wrong Man, too, to have a self-referential dimension. Like the surface of a mirror, the movie screen is a border between an image of reality and reality itself; it is also where the two touch. In this shot the mirror’s frame is outside the film frame, so the mirror’s surface fills the entire movie screen. Visually, there is nothing to distinguish one from the other. Thus the question of whether it is Manny we are viewing or his view of his own mirror image melds with other questions: From which side of the border separating his world from our world are we viewing Manny? On which side of this border is the camera? From which side comes the violent strike that fractures Manny’s image or self-image and freezes his face, turning it to stone? Is it Manny whom Rose believes she is striking, or has Manny become the embodiment of “they” to her? Or is it really “they,” reaching in from outside, who have possessed Rose, using her hand to wield a weapon to smash Manny down and make sure he cannot win?

Figure 10.7

That the “outside”—the other world to whose reality Rose’s violent act forces Manny to open his eyes, a world so close to their own that she is afraid “they” will reach in from it to smash them down—could be our world, the one existing world, is underscored by yet another dimension of the shot’s ambiguity. We cannot tell whether the fissure that splits Manny’s image is a crack in the mirror, a crack in the lens of the camera or projector, or a tear in the movie screen (is that the otherwise inexplicable sound we heard of tearing canvas?). If the vertiginous spinning of Manny and his world declared the transience that is one aspect of film’s temporality, the present disturbing vision of Manny’s disturbing vision—visually, this is a moment of stasis—declares the timelessness that is film’s other aspect—the fact that in the projected world past, present, and future, as well as “inner reality” and “outer reality,” are equally real and unreal, and in the same way. It is as if for all time that Manny’s face is frozen, his mismatched eyes staring at us, staring into the abyss.

The agitating train sound segues smoothly into Bernard Herrmann’s now soothing music. Her passion spent, Rose goes over to Manny, her hands reaching toward his face in a supplicating gesture, as if begging his forgiveness for having forced his eyes open to see the reality of her madness—and see the truth in her madness. Tenderly, she pulls his face down to hers as if to kiss it, but thinks the better of it. She looks past him, as if it is fully sinking in that she is alone.

Then, staring at the hand that had held the hairbrush, Rose turns away from Manny, goes back to the chair between the bed and the lamp, the camera following her, and sits down again, her hands crossed, as if to keep them from once more betraying her innermost feelings. “It’s true, Manny,” she says sadly. “There is something wrong with me. You’ll have to let them put me somewhere.” Manny, who does not comprehend what has happened, is silent as the scene fades out.

When Marion Crane intimates to Norman Bates, as tactfully as she can, that it might be best if he put his sick old mother “some place,” he replies with a flash of anger, “You mean an institution? A madhouse?” He characterizes such a place as one where there are always “cruel eyes studying you”—not coincidentally a description that could aptly be applied to the world of Psycho, the “place” they are in as they are conversing. Rose may well believe that at this moment “they” are looking at her from the “outside,” as we actually are, but what she fears is not their “cruel eyes,” or ours. She fears the things “they” have done, and threaten to do, when they “reach in” to her world—the power they possess, and their intention, to “smash her down.”

Figure 10.8

Rose believes, I take it, that what has just happened—what she has just seen, what she has just done—has revealed two things to her. Manny’s hand—even though it isn’t missing the top joint of its little finger—has unmasked him as one of “them.” And her own hand has revealed its capacity for violence. The “somewhere” Rose tells Manny he will have to let them put her is a place—a “private island”—where she believes she will be free, or at least freer, from the threat that “they” will smash her down. Specifically, it is a place where Manny can be locked out, except for brief visits, keeping Rose safe from him but also keeping him safe from her.

Before Manny agrees to let Rose be put in an institution, her doctor explains to him that his wife has suffered a mental breakdown resulting from her unbearable feelings of guilt, her belief that her inadequacies are the cause of all Manny’s suffering. Now she is “living in another world” from theirs, the doctor tells Manny, a place that could just as well be “the dark side of the moon.” In that world Manny is there, the doctor assures him, but only as a monstrous shadow of himself, not as he really is—a projection of Rose’s inner reality, not reality itself. Of course, the doctor’s words aptly describe the world of The Wrong Man, implicitly equating our perspective with that of Rose, not Manny.

In a Hitchcock film it is always a mistake, however, to assume the veracity of a psychiatrist’s explanation. At the end of Psycho, for example, one assumes at one’s peril that the psychiatrist gets it right, that it really is “Mother,” not Norman, who has filled him in on the situation; thus, we err if we simply take for granted that it is “Mother” who is casting that villainous grin directly to the camera. Norman, who prides himself on being someone who can’t be fooled (“not even by a woman”), would find it child’s play to bamboozle this psychiatrist, who is such a slick, self-important know-it-all. Rose’s doctor is more sympathetic, but it would likewise be a mistake simply to take his word for it that when Rose, in a “private island” that could be “the dark side of the moon,” perceives Manny as saying “hateful things,” she is not perceiving Manny as he is but only his “monstrous shadow,” a projection of her own broken mind. Surely, the Manny that Rose perceives in her madness is real—the Manny who doesn’t listen to his wife even when it is crazy for him not to; the Manny who borrows, borrows, borrows without a plan to pay the money back; the Manny who has secret fantasies of solving all his problems by winning big at the racetrack but who is afraid to take the risk of betting; the Manny who, for all his good intentions, perceives his wife as a satellite of himself.

Manny’s response to the doctor is a testimonial to his love for his wife, to be sure, but his words also betray what Rose, in her madness, would have reason to find hateful. “I want only the best for her,” he says (not, for example, “She deserves the best”)—as if what he wants is what really matters to Manny. When he repeats, emphatically, “The best,” it is obvious that he is giving no thought to how expensive “the best” will be, to the money they will have to borrow to pay for it, to how much deeper this will dig the hole out of which they already have no way to climb. Evidently, the reality he glimpsed in the cracked mirror failed to shock Manny sufficiently to provoke him to change. His eyes are again shut.

Rose does have to be paranoid—most Americans were, in the mid-1950s—to say, and believe, “They’ve got it fixed so that it goes against you,” and “No matter how innocent you are or how hard you try, they’ll find you guilty.” Yet Manny would almost certainly have been found guilty were it not for a totally unexpected occurrence, the happy accident—happy for Manny, at least—that the real holdup man returns to the butcher shop that was the scene of one of the crimes the police believe Manny committed, is arrested after he tries to hold up the store a second time, and is brought to the police station at precisely the moment the younger (and more sympathetic) of the two detectives who had originally questioned Manny walks by. His memory jogged, the detective puts two and two together. The result is that the case against Manny is dropped. A highly unlikely succession of accidents—a miracle, in effect—has to occur for Rose’s dark prophecy to fail to come true. Or perhaps it does come true after all, since even when Manny’s court case is thrown out, Rose does not let him win. Her hateful words, “That’s fine for you,” pronounce him guilty.

In the film’s most celebrated passage, the camera not only enables us to bear witness to the “miracle” that leads to Manny’s exoneration in the eyes of the Law; it is also instrumental in making the “miracle” happen. The passage begins when Manny’s mother, sensing that her son’s faith is faltering, asks him if he has prayed. He prayed for help, he tells her. Unhappy with this, his mother implores him to pray for strength. With a rare trace of anger—anger at his mother and, perhaps, at God—Manny replies that what he really needs is a little luck. Saying “I’ve got to go to work,” he abruptly leaves the room. His mother silently prays.

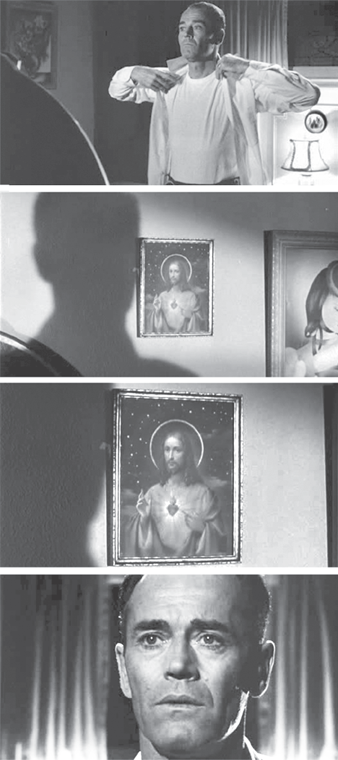

Alone in the bedroom, Manny is putting on a dress shirt when something offscreen strikes his attention. Is he seeing his own reflection in the still-cracked mirror? When we do cut to his point of view, what we discover, rather, is that Manny is staring at the portrait of Jesus we had glimpsed on the wall just before Rose’s violent breakdown. In this strikingly composed frame—a setup that Hitchcock first used in The Lodger and was to use again in Vertigo at the all-important moment Scottie recognizes the telltale necklace—Manny’s shadow is in the left foreground, while in the right background Jesus, in the painting, seems to be meeting the gaze of Manny’s shadow. That the camera is moving closer to the painting, all the while keeping Jesus’s eyes centered in the frame, enhances our sense that the painted Jesus’s gaze, like a magnet, is pulling Manny’s gaze—and the camera’s—toward it. This is a shot from Manny’s point of view, yet it is not Manny’s own gaze, but that of the painted Jesus, that presides over this frame. When the camera returns to Manny, he is framed differently from the way he had been. When we now view Manny, moving his lips in silent prayer, he is framed in a nearly frontal close-up. It is as if this shot represents not a conventional reaction shot but a shot from the painted Jesus’s point of view. This shot is less striking, visually, than the preceding shot, which juxtaposed Manny’s shadow and the painting, but it is no less mysterious. The sense of mystery the shot conveys is enhanced by the fact that Manny’s face is framed by a curtain—always, in Hitchcock, an allusion to theater—whose folds form a perfect Hitchcockian ////.

Figure 10.9

Is Manny following his mother’s advice and praying for the strength she believes he needs to carry the heavy cross God has chosen for him to bear? I imagine that Manny’s mother is now praying for God to grant her son strength but that he is praying for the real holdup man to be arrested—the “good luck” he believes is the only thing that can help him. And that is what is about to occur, although Manny will not immediately be aware that his prayer has been answered. A long, slow dissolve now begins to superimpose Manny’s face, his lips still moving in prayer, and a New York street at night, lined with brightly lit storefronts—one shot marked by the //// motif, the other forming a Hitchcockian tunnel shot.

At first a small figure in the depths of the frame, but growing ever larger as he strides directly toward the camera, is a man wearing a raincoat and a hat just like Manny’s. (Marian Keane pointed out to me that it is probably no coincidence that the hat the Italian American Manny likes to wear looks so much like the protagonist’s hat in Vittorio De Sica’s Italian neorealist classic The Bicycle Thief [1948].) As the man draws closer and closer to the camera, he looms ever larger until his face, superimposed over Manny’s, or perhaps under it, rises in the frame until—this is a breathtaking moment—the contours of their faces coincide. For a moment their features do not quite fit together, and we may well be reminded of our earlier view of Manny’s face—or of Manny’s view of his own face—in the cracked mirror. At the precise moment their faces do perfectly meld into one, this man’s eye-line matches Manny’s, as if his gaze, like Manny’s, is drawn by the power of Jesus’s gaze, thus as if the camera is viewing him with Jesus’s eyes.

When the man looks screen right, severing his gaze from Manny’s, his expression is grave. He lowers his eyes, as if in shame. It is at this point that it fully sinks in that the camera, perhaps animated by Jesus’s gaze, has transferred its attention, and ours, from Manny to this stranger. When he turns in the opposite direction and begins walking, he is grim-faced, having made the fateful decision, as we will momentarily discover, to pay a return visit to the butcher shop.

When Manny is exonerated, justice is served. Yet we may well find it troubling, if understandable, that in praying for his trial to end, Manny is praying for another man’s trial to begin. No doubt, that man is a criminal who has a very different story from Manny’s. But he has a story, as every person does, a story that remains unknown to Manny—and to us. We may well also find it troubling, if understandable, that when their paths “accidentally” cross in the hallway of the police station, Manny angrily confronts the newly arrested man, saying, “Do you know what you’ve done to my wife?”—as if Manny himself bore no responsibility at all for her descent into madness. That is not how Rose, in her madness, sees it. But Manny’s eyes are shut. And they will still be shut when he brings his wife the glad tidings that their nightmare is “all over,” only to be rebuked with the words, “That’s fine for you.”

Figure 10.10

It takes an unlikely conjunction of “accidents”—a “miracle”—to cause Manny’s court case to be dropped, just as it took an equally unlikely conjunction of “accidents”—another “miracle”—for him to have been arrested in the first place, and yet another for his alibi to have been “spoiled,” as Rose put it. In the preceding chapters we have repeatedly observed that in the world of a Hitchcock film everything that happens only happens because Hitchcock makes it happen. In the films I’ve discussed, everything that happens within the film’s world is a manifestation of Hitchcock’s power as the film’s author; in that sense, we can say that everything that happens is a miracle. From the outset, however, The Wrong Man claims to be different. It opens with Hitchcock himself, doubled by his shadow, speaking directly to us to testify that the story this film tells—“every word of it”—is true.

Although Psycho opens with titles that specify the time and place of the camera’s entrance into the hotel room where Marion and Sam have just had illicit sex, that film’s suggestion that the events actually happened is only a rhetorical device. In The Wrong Man, though, Hitchcock’s personal appearance seems to lend his full authority to the claim that, as we might put it, reality itself is the real author of this film’s script. And, indeed, the film’s story does follow, at least in broad outline, events in the real lives of, among others, Emanuel Balestrero; his wife, Rose; and a young lawyer, Frank O’Connor, who was to go on to become a well known New York City district attorney. Their names aren’t even “changed to protect the innocent” (or the guilty).

Near the end of Lifeboat, Connie lectures her fellow Americans, in an Emersonian spirit, on the need for self-reliance, then practices what she preaches by using her prized necklace as bait to try to land a fish. Just as a humongous fish, no less committed to self-reliance, seems about to risk a bite—an underwater shot adds a wonderfully absurd comic touch—Hitchcock cuts to Joe. A man of faith, like most black characters in Hollywood movies of the 1940s, he is looking toward the horizon with a prayerful expression. When his face lights up and he announces that he sees a ship, we understand that he perceives the ship’s arrival as providential. A miracle. This ship, it turns out, is the German supply ship toward which Willi had been secretly steering the lifeboat. By answering Joe’s prayer, God, whether owing to cruelty or incompetence, seems only to have made things worse. Joe’s faith isn’t shaken, though. He knows that God works in mysterious ways. So does Hitchcock. In a twist reminiscent of Secret Agent, an American plane suddenly appears and sinks the German ship. Had Joe’s prayer not been answered, the lifeboat wouldn’t have been close enough to the German ship for the bomber pilot to spot it and rescue all on board—but not before they pull a young German survivor from the water and overcome the temptation to kill him.

Joe has no doubt that God has performed a miracle. We know better. We know that the film’s author, not God, is the responsible party. But if we accept The Wrong Man’s claim, voiced by Hitchcock himself, that this film is different because everything that happens in its world actually happened in our world, how are we to account for all those unlikely conjunctions of accidents, those “miracles,” around which the film’s story revolves (as does every Hitchcock story)? In the world of Lifeboat there are no accidents, only “accidents”; no miracles, only “miracles.” But every “miracle” in the world of The Wrong Man, Hitchcock tells us, represents an event that actually happened in our world. In the one existing world, those events must either have been coincidences pure and simple—true accidents, not “accidents”—or else they were acts of God—true miracles, not “miracles.” Which were they?

For other Hitchcock films, such a question would be moot. In their worlds there are no accidents, only “accidents,” and every “accident” bespeaks the power of the film’s author and is a miracle, in that sense (but only in that sense). In our world such a question is not moot, but neither does it admit of a definitive answer, because we can never adduce tangible evidence that can definitively distinguish “accidents” from accidents or “miracles” from miracles (if there are such things as miracles). This would seem to be the case, as well, in the world of The Wrong Man, if we accept the film’s claim that every event within its world has its counterpart—whether “accident” or accident, “miracle” or miracle—within the one existing world.

But what of those extraordinary moments in the film, major turning points in its allegedly true story, in which it is not even possible to describe what is happening within the film’s world without taking into account what the camera is doing—especially the moments that manifest the camera’s power to anticipate what is going to happen and even to make things happen. (Are these powers of the camera in principle separable?) Obviously, no camera was in the presence of the “real” Emanuel Balestrero when the events represented in The Wrong Man took place. Awareness of that fact had always convinced me that what happens in this film’s world at such moments couldn’t possibly have actually happened, hence that we should not take at face value Hitchcock’s claim that the film’s story is literally true.

I now question that conviction. I now realize that I had been overlooking the implications of the crucial fact that, as I’ve put it, the camera that was in Henry Fonda’s presence but not in the presence of the “real” Emanuel Balestrero, is not in the presence of the film’s Manny, either—the character Fonda plays, and incarnates, within the world of The Wrong Man. Or rather, the camera is a presence in Manny’s world but only as an absence. Manny lacks Rose’s clairvoyance, but the God who is a reality to him is an “absence-that-is-also-a-presence” with powers comparable to the camera’s in films Hitchcock unambiguously authors—the power to make miracles happen, to make his world go ‘round, to split him in two, to answer his prayers.

Does our world have an author who presides over the world of His (or, more likely, Her) creation the way Hitchcock presides over the worlds of his films? I don’t claim to know. Nor do I claim to know whether Hitchcock really believed in such a God, even though he was a Catholic who regularly attended Mass throughout his adult life. But I do know that Manny believes that God exists, however much his mother has to jog his faith when it is most tested. And if everything that happens in the world of The Wrong Man actually happened in our world, Emanuel Balestrero, Manny’s “real” counterpart, prayed before a portrait of Jesus, just as Manny does, the night the “right” man was arrested.

Manny does not exist in the same world as Emanuel, but they pray to the same God. The thrilling slow dissolve by which the camera effects the transfer of its gaze and ours from Manny, praying, to the real holdup man manifests itself to us, but not to Manny, who doesn’t see what the camera enables us to see as God answering Manny’s prayer. In all his other films Hitchcock uses the camera to perform his own miracles. Here, he is using the camera to represent or reenact a miracle—a miracle originally performed by God, not by Hitchcock.

Earlier, I observed that in his role as author Hitchcock could play God without being God because the worlds of his creations, over which Hitchcock presides, do not really exist. Within those projected worlds, I argued, Hitchcock possesses godlike powers, but his powers have limits. He cannot make himself God. This means, for example, that he cannot grant himself the power to absolve murderers. After making the bus blow up in Sabotage, killing the protagonist’s likable young brother and the lovable puppy he befriended, the intuition dawned on Hitchcock, or so he told Truffaut, that killing the boy and the puppy, for no reason other than that he wanted to, was wrong. It didn’t make Hitchcock a murderer. Nonetheless, it troubled him.

The Wrong Man is an unusual Hitchcock film in that its story doesn’t revolve around murder. But it is altogether unique, among Hitchcock films, in being a story of unrelieved suffering—unrelieved for the characters we care about and unrelieved for us by virtue of the total lack of the kinds of gratifications other Hitchcock films offer us. For example, it has none of the humorous moments he relies on in all his other films, with a mastery rivaling Shakespeare’s, to vary the mood or our perspective on the action. In the Hitchcock films we’ve examined so far, and the ones we will examine in later chapters, sympathetic characters suffer at times, but also enjoy pleasurable moments. And almost without exception—Rope is an exception—they are ultimately rewarded (although, as we have seen, Hitchcock also undermines, or hedges, some of these “happy endings”).

I am not suggesting that The Wrong Man rewards us with no pleasures at all. For one thing, it rewards us with great, and singular, beauty. If other Hitchcock films are trains of moods, dazzling strings of beads of different colors, this film’s story of unrelieved suffering allows, or rather requires, the telling of its story to sustain a single mood, a darkly poetic mood that casts an ever-deepening hypnotic spell over us.

The fact that the protagonist is Manny, even though Rose is the heart and soul of The Wrong Man, is a key to the film’s ability to keep us entranced. As played by Henry Fonda in an inspired and technically flawless performance, Manny seems to be sleepwalking through life. His behavior has an almost preternatural even-tempered calmness not because he is clairvoyant, like Rose, but because his eyes are shut to what Rose sees. Working in tandem with Bernard Herrmann’s spellbinding score, cinematographer Robert Burks employs several strategies to attune the film visually, with exceptions that prove the rule, to Manny’s subjectivity, not Rose’s. As in those hypnotic passages in Vertigo in which Scottie, following Madeleine’s car, drives what seems endlessly through the streets of San Francisco, throughout The Wrong Man, shot smoothly follows shot, and the camera moves, when it moves, in a slow, even tempo that lulls us into a trancelike state between sleep and wakefulness.

Figure 10.11

And Burks doesn’t use black and white expressionistically, as John Russell does in Alfred Hitchcock Presents episodes and in Psycho, to project a world of stark melodramatic contrasts. The Wrong Man feels less like a black-and-white film à la Psycho than a color film in whose world shades of gray happen to be the only colors. To this end he employs a range of grays, the way he uses colors in other Hitchcock films of the 1950s, to divide the frame into regions, separated by distinct borders. The juxtapositions of these regions create satisfying two-dimensional compositions that make us register, consciously or not, the flatness of the screen that holds these projected images of a world in three dimensions. This strategy enhances our uncanny sense that we are dreaming this calm, gray, beautiful world rather than viewing it wide awake. It makes us all the more vulnerable to the brutality of those moments when Rose’s subjectivity reaches into our dream and turns it into a nightmare.

Vertigo and Psycho are dark films, too. But only The Wrong Man, for all its beauty, is so unrelentingly harrowing that it irresistibly invites comparison with the book of Job. Job suffers for a reason, even if the reason is God’s wish to teach his creations the painful lesson that they are not to question His reasons. God does not need a reason to make His creations suffer. But Hitchcock isn’t God. The “mistake” he made in Sabotage helped bring home to him that he needs a reason to make his creations suffer—even though the characters in his films don’t really exist, even though making them die doesn’t make him a murderer, and even though he is powerfully drawn to the idea that each man kills the thing he loves.

I can believe that Manny suffers for a reason, but I cannot believe that Rose does. Nor can I believe that Hitchcock believed there was a reason to make her suffer. Why does he make her suffer, then? The simple answer is that he doesn’t. In his role as the author of Notorious, Hitchcock makes Alicia suffer, and he does so for a reason (a reason related to the fact that Devlin is an accomplice in making her suffer, as is Alicia herself). But if we accept his claim that The Wrong Man is different from his other films in that everything that happens in its world actually happened, it follows that Hitchcock is not responsible for Rose’s suffering, the way he is for Alicia’s. How could Hitchcock be responsible for the suffering of the film’s Rose if her suffering only represents the actual suffering of the “real” Rose Balestrero?

Hitchcock’s claim that the events in The Wrong Man actually happened constrained him, however, in at least two ways. One is that, if only for legal reasons, there are things the film cannot say. For example, it cannot say—I am not implying that this was really the case—that the two detectives who arrest and question Manny actually frame him, much less that framing suspects they believe to be guilty is standard procedure for New York’s finest. The detectives dictate to Manny the words of the holdup note and make him write them on a slip of paper. Looking at the original, the copy, and each other with what seems feigned amazement, they hand him another slip of paper and dictate the words again. After another theatrical exchange of looks, the older detective says, in the most Kafkaesque moment of this Kafkaesque scene, “It looks bad for you Manny. It really looks bad for you.” He then informs Manny that he had misspelled the word drawer, just as the holdup man had done. I always have the impression that the detectives are brazenly pulling a “three-card Monte” number on the gullible Manny, that both slips of paper with the misspelled word are the ones Manny wrote. As a consequence of his claim that everything that happens in the film’s world actually happened, however, Hitchcock wasn’t free to make the film unambiguously assert, even if he wanted to, that New York City detectives routinely break the law when they interrogate suspects.

A deeper consequence of Hitchcock’s claim that this film tells a true story is that he cannot in good conscience end the film with Rose’s devastating words to Manny, “That’s fine for you.” That would have made a powerful and meaningful ending. But it would have exposed these two characters so abjectly, so cruelly, without suggesting that there was even a hope for their redemption or salvation, that the “real” Emanuel and Rose Balestrero would surely have perceived the film as hateful and would have been painfully wounded by it. This ending would have inflicted on these two vulnerable people “little deaths” of great magnitude.

It would have been less cruel for Hitchcock to have ended the film with the nurse’s kind words to Manny, spoken as he is leaving, which hold out to him, and us, a ray of hope. “Miracles do happen,” she says in a caring voice, “but they take time.” Ending the film with this line, however, would have meant withholding from us the fact—surely, a telling feature of the “true” story—that such a “miracle” actually happened in the lives of the Balestreros, who moved to Florida after Rose’s condition improved sufficiently for her to be released from the institution. Hence Hitchcock concludes the film with a shot of the skyline of Miami, then still a sleepy southern town, over which he superimposes a title informing us that this is where the family is now living happily, Rose having left the institution “completely cured.”

This title may seem congruent with—even mandated by—the actual lives of the Balestreros, but it unmistakably smacks of that irony familiar from Hitchcock’s appearances as host of his television show—as if The Wrong Man were an episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and this is the “happy ending” his sponsors demand. Presumably, the “real” Rose Balestrero wouldn’t have been released were her doctor not convinced that she was well enough to make the long journey to Miami from “the dark side of the moon.” In The Wrong Man, though, as we have seen, there is reason, as well as madness, to Rose’s madness. Does being “completely cured” imply that Rose no longer perceives, in Manny’s words and actions, what it was not madness for her to have seen as hateful?

I’d like to think that in encouraging Manny to hope for a miracle, the nurse understands that any miracle that changed only Rose but left Manny unchanged would fail to cure what ails their marriage. To transform their troubled relationship into the kind of marriage that couples achieve in comedies of remarriage (and, as we will see, in North By Northwest), a further miracle would be required, one that moved Manny to open his eyes. It would take more than time to make that kind of miracle happen. Part of what Manny would see, if he opened his eyes, is that there is no such thing as a “complete cure” for his condition, or Rose’s. This is true of our condition as well. That being human means being finite, having frailties, is an intuition that Hitchcock, as well as Emerson, shared with the Katharine Hepburn character in The Philadelphia Story. The human condition is terminal. The only “complete cure” to being human is one that it is madness to prefer to the condition itself.

Figure 10.12

Hitchcock concludes The Wrong Man by asserting a claim—a claim about both the film’s world and our world—that I don’t believe he believed to be literally true, the claim that Rose is “completely cured” when she is released from the institution. Thus the film’s ending calls into question the claim Hitchcock personally voices at the opening of the film, the claim that this film is different from his other thrillers in that it tells a story every word of which is true. The more I contemplate the film’s opening, however, the more mysterious it reveals itself to be, and the more it appears also to be calling into question the very claim it is nonetheless seriously asserting. Again, what could be more Hitchcockian?

“This is Alfred Hitchcock speaking,” we hear that familiar voice say, but in a tone devoid of its usual irony. “In the past,” the voice goes on, “I have given you many kinds of suspense pictures. But this time, I would like you to see a different one. The difference lies in the fact that this is a true story—every word of it. And yet it contains elements that are stranger than in all the fictions that have gone into many of the thrillers that I’ve made before.”

Hitchcock’s voice, speaking these words, is accompanied by the same Philip Glass-like music that will be reprised when Manny, alone in his prison cell, finds his world vertiginously circling. And Hitchcock is filmed—he films himself—from afar within as weirdly composed a shot as he had ever created.

As he begins to speak, Hitchcock walks toward the camera, much as the “right” wrong man will later do. Or is this really Hitchcock? Rendered strangely small by the camera’s distance, silhouetted against, and centered horizontally within, a triangle-shaped pool of light that pierces the darkness surrounding it—this triangle at once evokes the beam of light that is projecting this image onto the movie screen and turns the image into one of Hitchcock’s signature tunnel shots—this figure could be anyone. Or no one. That this figure is doubled by its own monstrous shadow, twice as long as the figure is tall, might well remind us, in retrospect, of the language in which Rose’s doctor describes “the dark side of the moon.”

This association is enhanced by the fact that we may find ourselves wondering whether that familiar voice, sounding impossibly close, is emanating from the silhouetted figure we take to be Hitchcock “as he is,” or from the monstrous shadow he casts within the frame. There are no villains in this film’s world—unless we count the ones Rose calls “they,” in which case there is no one we can be certain is not a villain, and that includes Manny, and it includes Rose herself. It also includes Hitchcock, the film’s opening is telling us in its singular way.

When the court case against Manny is dropped, he believes his suffering is over and that, therefore, Rose’s suffering will be over, too. But Rose, in her madness, is unable, or unwilling, to stop suffering. And she will not allow Manny to stop suffering, either. As usual, there is reason in Rose’s madness. What justice would there be if Manny, whose eyes are closed to the guilt he bears, were allowed to stop suffering, while Rose still suffered?

I’m not suggesting that Hitchcock took pleasure in Rose’s suffering. I feel that he empathized deeply with her. And I’m certainly not suggesting that Hitchcock saw Rose, or that Rose sees herself, as a victim to be pitied or as a damsel in distress to be rescued. Nor is Rose perverse, like Alicia, who participates actively in her own victimization by demanding—as Ingrid Bergman characters are wont to do, with Spellbound a glorious exception—that the man she loves do the thinking—or, at least, the speaking of words of love—for both of them. Manny’s misfortunes, and her own, are in no way Rose’s doing—except for the madness she suffers. And she brings her madness on herself by virtue of what I have called her clairvoyance.

In light of The Wrong Man’s claim that its story is true, hence that it is not Hitchcock who presides over the film’s world but rather God, the author of our world, Rose’s clairvoyance reveals her kinship with the heroines of Carl Dreyer films who sense God’s presence in ways the films’ other characters do not. Since Rose envisions the divinity that holds sway over her world, and whose nearness she alone senses, as the terrifying “they” who have singled her out only because they want to smash her down, Rose’s clairvoyance seems a curse, not a privilege or a blessing.

Job learned the old-fashioned way that God needs no reason, other than wanting to do so, to make his creations suffer. That we must not only accept, but also affirm, God’s dominion over us is the little moral to which the book of Job points, the little lesson it teaches. Is this the lesson The Wrong Man teaches as well? Because in reality, as Rose sees it, “they” want to smash her down, she refuses to affirm the reality she sees, but she also will not, or cannot, close her eyes to it to become “a sleepwalker, blind,” like Manny. Is it seeing that “they” really want her to suffer that causes her madness? Or is it her madness that causes her to see reality this way?

If Hitchcock believed in a God, the creator of our world, capable of wanting to smash down the likes of Rose Balestrero, it is no wonder he never chose to repeat the experiment of ceding his authorship to such a God. In any case, as great a film as I believe The Wrong Man to be, when Hitchcock uses the camera to represent or reenact miracles, rather than to perform miracles of its own, the Emersonian dimension of Hitchcock’s art is inevitably submerged. Submerged, but not lost, I must add. For even if God wanted to make the “real” Rose Balestrero suffer, it would not be possible for the film’s Rose to suffer the way she does in The Wrong Man if she kept her eyes closed to that reality. God cannot make Manny open his eyes. And God cannot make Rose open hers, either. Rose’s suffering in the film, like Elsa’s in “Revenge,” is not a sign of weakness but rather a manifestation of a freedom she claims for herself, a power she possesses. This power intrigued as well as moved Hitchcock, perhaps not only because, like all masters of the art of pure cinema, he possessed that power himself. (How else could he have perceived it in Vera Miles?)

Rose is a mystery to Hitchcock in a way only Elsa, among his characters, had ever been before. If one of God’s creations can claim the freedom to impose her will on God, is it possible for a character in a film Hitchcock truly authors—a character he creates rather than a character who represents a “real” person—to impose her will on the film’s author, even make Hitchcock, against his will, kill the thing he loves? Pondering this question gives me vertigo. Pondering this question moved Hitchcock to give us Vertigo.

When I began writing this chapter, I had high hopes that when a movie was one day made of my life, it would end with a title announcing that I had moved with my wife to Miami, not far from the happy home the Balestreros made for themselves after Rose was released from the institution, and that I was “completely cured” of the dark vision I had found to be at the heart of Hitchcock’s work, and that was at the heart of my book as well, when I wrote The Murderous Gaze. As I am writing these words that are at long last bringing this chapter to a close, I’m not so sure. It is bleak midwinter in most of the country, but outside my window, birds are singing. Am I speaking to you, in this chapter, from sunny Miami? Or are these words coming to you from “the dark side of the moon?”