At the end of Vertigo Scottie, like Stefan at the end of Letter to an Unknown Woman, awakens too late to his failure to recognize the woman he loved. In “Vertigo: The Unknown Woman in Hitchcock,” an essay I published several years after The Murderous Gaze, I reflected on the intimacy of Vertigo’s relationship to the Hollywood genre that Cavell, in Contesting Tears, calls the “melodrama of the unknown woman.”1 (In addition to Letter from an Unknown Woman, the other members of the genre Cavell’s book studies are Stella Dallas, Now Voyager [Irving Rapper, 1943], and Gaslight.) Vertigo’s Judy, in her quest for existence, is close kin to the women in these melodramas. So are a number of other women in Hitchcock thrillers. And yet, as I argued in my essay, the role of the villainous Gavin Elster, and Judy’s implication in his plot to murder his wife, sets Vertigo apart from an “unknown woman” melodrama like Letter from an Unknown Woman, a comedy of remarriage like The Lady Eve, or a member of an adjacent genre, like Random Harvest (Mervyn LeRoy, 1942)—all classic Hollywood films about a woman in love with a man who fails to recognize her.

In the years since I wrote “Vertigo: The Unknown Woman in Hitch-cock,” I have come to see Hitchcock’s masterpiece with new eyes and have arrived at a new understanding of its crucial importance within his career as a whole. Vertigo, his one tragedy, is a turning point for Hitchcock.

The specific circumstance that provoked me to think about Vertigo in a new way was coming across on the Internet a brilliant if perverse essay on this, his favorite film, by the great French filmmaker Chris Marker. Marker offers an audacious twist on the idea that Hitchcock designed Vertigo to deceive us and that Gavin Elster is his stand-in. Marker’s interpretation motivated me to look more closely at Scottie’s dream sequence (if that is what it is) and at Judy’s flashback. Then my eyes were opened.

Scottie’s Dream

Marker interprets the last third of Vertigo as Scottie’s wish-fulfillment dream or fantasy. According to his interpretation, our last glimpse of reality is a shot of Scottie sitting in his hospital room—or is he on “the dark side of the moon”?—as Midge (Barbara Bel Geddes) plays Mozart to “chase the cobwebs away” (although she knows he has an aversion to the composer) and assures him that (in her chilling words) “Mother is here.”

In reality, Marker argues, Scottie never leaves his chair; he is absorbed in a fantasy designed to assuage his unbearable guilt for causing the woman he loved to die by denying that she really is dead. During the last third of the film, in Marker’s view, nothing the camera presents is reality; every-thing—Elster’s plot to murder his wife; Scottie’s project of changing Judy into Madeleine; indeed, Judy herself—is a projection of Scottie’s inner reality. Like Norman Bates’s efforts to breathe life into the mother he murdered, Scottie’s dream is a broken mind’s way of denying a reality it finds intolerable. What begins as wish-fulfillment turns into nightmare. The repressed returns as Scottie, within his fantasy, again causes the woman he loves to die.

Marker’s claim that Vertigo deceives us into mistaking Scottie’s inner reality for reality itself has the virtue of recognizing a fundamental Hitchcockian principle: on film there is no inherent difference between what is objectively real and what is real only subjectively. That is what makes possible the signature Hitchcock practice of employing his powers as author to make the innermost wishes of his characters—wishes they are not even conscious of harboring—“magically” come true. In using his powers as author to make reality coincide with fantasy, his aim is not to deceive us into mistaking one for the other. As I argue in The Murderous Gaze, it is one of his strategies for declaring in a modernist spirit, as well as exploiting for emotional effect, the capacity of the art of pure cinema to overcome or transcend the opposition, which we ordinarily take for granted, between reality and fantasy.

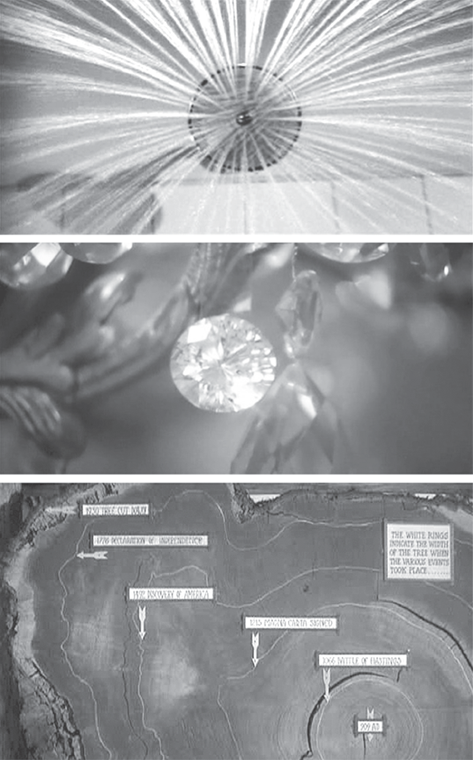

Figure 11.1

Because on film there is no inherent difference between what is objectively real and what is real only subjectively, filmmakers instituted conventions (cueing the beginning and ending of a flashback by making the screen go wavy, for example) in order to assert, against the grain of the medium, as it were, a real separation between them and to provide viewers with criteria to distinguish one from the other. In segueing to Scottie’s dream sequence, Hitchcock invokes one such convention by having Scottie look toward the camera as if a point-of-view shot (and, in turn, a reaction shot) were to follow. But Hitchcock complicates this transition between “outer” and “inner.” Instead of asserting a clear division between objective and subjective, the sequence is awash in ambiguity and paradox.

Scottie’s dream sequence begins with a dissolve to Scottie lying alone in bed, fitfully tossing and turning. Hitchcock cuts in to a closer shot, Scottie’s head framed by his white pillowcase. Without warning, the image turns blue. The blueness gradually intensifies, then subsides. Next, the image turns purple. Then, in waves or pulses, the purple begins switching on and off.

We know, or think we know, that these color shifts aren’t real. We take them to be conveying, expressionistically, the nightmarish quality of Scottie’s dream. We are not seeing what he is dreaming, the reality that exists only in his imagination. But we do take the pulsing colors to stand in for what he is dreaming. Partly because they are anxiety-producing to view, they convey the sense that Scottie is being assaulted by them, as if they originate from outside, not inside, his mind. Like the spiraling camera in The Wrong Man that at once expresses and causes Manny’s vertigo, they seem to be causing Scottie’s suffering, as if he would be able to dream peacefully, and be unafraid of waking, if only they ceased. (As we have seen, Hitchcock had experimented with pulsing colors in the ending of Rope, and this technique will of course be of great importance in Marnie)

Scottie seems to be struggling to open his eyes, as if waking might make the pulsing colors stop. At the same time, he seems to be struggling to keep his eyes closed, as if he feared awakening to find that his nightmare was real. When he does open his eyes and looks searchingly toward the camera, he seems wide-awake. Yet the pulsing colors go on. Are they real, then? Or is it only in his dream that he is no longer dreaming?

When Hitchcock first cut to this close-up, wrinkles in Scottie’s pillowcase visibly placed him as lying in bed. By the time he opens his eyes, the wrinkled pillowcase has morphed into a featureless background that offers no clue where he is. He could be anywhere. He could be lying in bed, or he could be sitting in a movie theater viewing Vertigo. And, as I have said, he could either be awake or only dreaming he is awake.

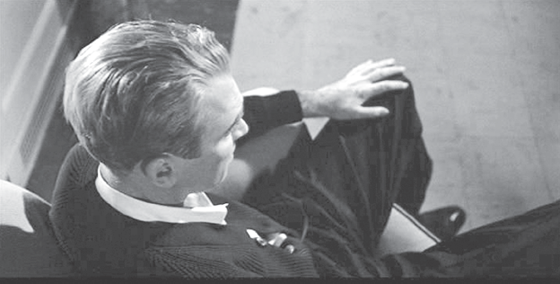

Common sense tells us that Scottie is either dreaming or not, that he cannot be both and cannot be neither. But in the world on film, which of these states really obtains at this moment is impossible to determine, even in principle. Like Wittgenstein’s “duck/rabbit,” we can see Scottie at this moment in two incompatible ways, either as awake or as dreaming. But we cannot see him both ways at the same time (except, perhaps, by splitting hares). Both possibilities are equally real. Both are equally unreal. The world on film is not reality. It is reality projected, reality transformed by the medium of film. Then what, in reality, is the world on film? This is a question Hitchcock ponders.

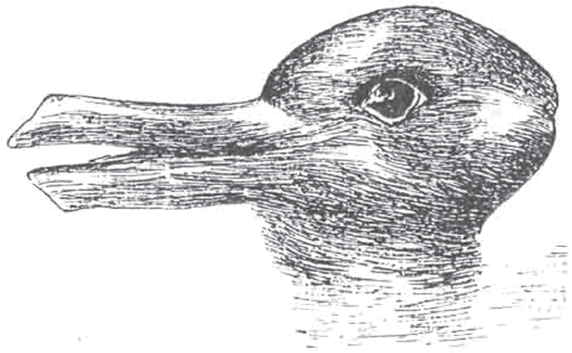

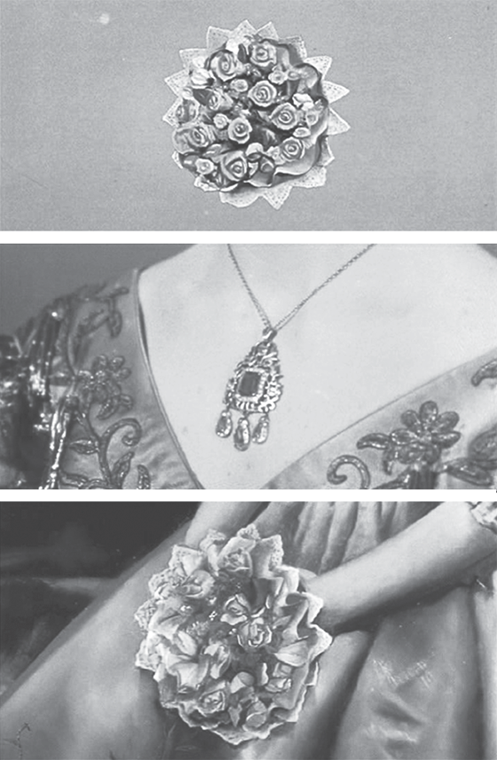

Although Scottie is looking at the camera, his gaze is unfocused, like Manny’s in his prison cell. This cues us that the next shot represents not his literal point of view but what he is imagining. The image that materializes is a stylized representation of the nosegay Scottie saw Madeleine buy at the flower shop, a perfect replica of the one in the portrait of Carlotta Valdes. This cluster of flowers, each like the facet of a jewel, framed against a smooth background, is linked, visually, to the jeweled necklace that is fated to play a crucial role in the film.

Hitchcock does not cut directly from Scottie to this “flower/jewel,” however. He fades out the former and fades in the latter. For a moment the screen is empty, withholding access both to objective reality and to Scottie’s inner reality. This vision of nothingness endures only a moment, but we have no standard for translating this moment of screen time, as we experience it, into its equivalent in “real time” within the world of the film (whether that be chronological time as a clock might measure it or time as Scottie subjectively experiences it). The moment of blankness, however brief, opens a temporal gulf that isolates Scottie, turned inward, from the “flower/jewel” that appears before us, born out of nothingness, and thus calls into question whether this is what he literally sees or is specifically what he does not see, or even imagine.

Figure 11.2

A Freudian would interpret this “flower/jewel” as a symbol of female sexuality. I see it as (also) an eye staring unblinkingly at Scottie. Viewed this way, the image of the “flower/jewel/eye,” which seems to represent Scottie’s inner vision, retroactively reveals the shot of Scottie that preceded it to represent what this “eye” is seeing. I take this “flower/jewel/eye”—like the showerhead that oversees Marion’s murder in Psycho (phallic when viewed in profile, a circle-within-a-circle when viewed frontally), the circular drain that receives her blood and then dissolves into her lifeless eye, the porthole that oversees what some take to be Mark’s rape of Marnie, and the diamond that all but winks at us at the end of Family Plot—to be a stand-in for (the circular lens of) Hitchcock’s camera. (I might add that the moment in Vertigo when Madeleine, standing beside Scottie in front of the cross section of a sequoia that had been cut down, points to the rings that correspond to her birth and her death irresistibly brings to my mind the opening of Emerson’s essay “Circles”: “The eye is the first circle; the horizon which it forms is the second; and throughout nature this primary figure is repeated without end. It is the highest emblem in the cipher of the world” [403].)

Figure 11.3

Figure 11.4

Alluding at once to the woman fated to die and to the perfect jewel, the “cold and lonely work of art” (to invoke the lyrics of “Mona Lisa,” the song “Miss Lonelyhearts” plays on her phonograph in Rear Window) that is Vertigo, the “flower/jewel/eye/circle” invokes the mystery at the film’s core—a mystery the film takes to be inseparable from the mystery of its own creation. It thus resonates with the film’s opening title sequence, which takes the form of a meditation on the birth of the projected world. Vertigo initiates what becomes a signature Hitchcock practice of incorporating such a meditation within each film’s opening title sequence, as we will see in our discussions of North by Northwest, Psycho, and Marnie. (My concluding chapter reflects on this practice, which is one of the surprising affinities between Hitchcock and Emerson, whose great essay “Experience” envisions itself, precisely as North by Northwest does, as pregnant with itself, as giving birth to itself. And Emerson’s essay ends, as Hitchcock’s film does, by returning us to its beginning.)

In Vertigo’s title sequence, “IN ALFRED HITCHCOCK’S” is superimposed over an extreme close-up of a woman’s eye, looking at Hitchcock’s invisible camera, which is looking at her looking at it. Inside the circle-within-a-circle that is this eye’s black pupil, precisely centered in the frame, the title “VERTIGO” appears, a pinpoint of light that expands until it spans the width of the eye. Then this title is replaced by a spiral, shaped like a galaxy, that emerges from the circle of the eye’s pupil and expands until it fills the frame. Elaborating on the circling of Manny’s world, with him within it, in The Wrong Man, the spiral’s circular movement, like a whirlpool, pulls our gaze into the blackness of the circle at its center, from within which a new spiral is born, and so on.

It is as if the chase sequence that ensues (which ends with Scottie suspended over an abyss with no conceivable way of being rescued) and, indeed, the entire film for which this chase sequence serves impossibly as a prologue, is envisioned, or conjured, by this eye, or as if the world of Vertigo is born out of the mysterious black circle at its center.

In Scottie’s “dream” sequence, no sooner does the “flower/jewel/eye/circle” materialize out of the blank frame than it is subjected to, or subjects us to, the pulsing colors. It is at this point that Hitchcock begins to animate the image. To me, the Disneyesque animation isn’t effective; in my experience it undercuts, rather than enhances, the gravity and mysteriousness of the sequence. (I am no fan of Spellbound’s dream sequence, either.) But whether or not the animation “works,” it is important to grasp the thinking that underlies it. First, the outer fringe disappears. Then the petals drop away, causing the image to fragment. I had never noticed this before, but there is a moment when at the center of this jumble there appears a form, at once a circle and a spiral, that is like a miniature “flower/jewel/eye/circle” and at the same time seems to resonate with the spiral “galaxy/eye” of the opening credits.

Figure 11.5

Both associations are confirmed, I take it, when the petals part, opening a yawning hole that draws the camera into it, engulfing the frame in blackness. From this blackness emerges the most enigmatic shot in the film. It duplicates the framing in which Gavin Elster, after the inquest, has the chutzpah to say to Scottie, “Only you and I know who really killed Madeleine.” What makes the present shot different is the woman standing next to Elster. Silhouetted against the window, more shadow than flesh and blood, looking at neither man, she is turned inward, like the ghost at the end of Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu (1953), mindful that she must return to the dead as soon as she completes her unfinished business on earth. Then a color shift reveals this woman to be, or seem, real. Plainer than Kim Novak (who isn’t?), she is a woman we have never seen before. As she turns her head to cast an accusing gaze at Scottie, we see that she is dressed like Carlotta in her portrait.

Figure 11.6

The shot that follows presents a painted image of this woman, viewed from Scottie’s perspective, looking toward the camera out of the corner of her eye. Like the cracked mirror in The Wrong Man, this painted image has no visible frame. Thus it seems to be the gaze of the “real” woman, not the painted one, that solicits the camera, which still seems to represent Scottie’s point of view, to move in on and center her jeweled necklace. Like the “flower/jewel/eye/circle,” this necklace seems to have a gaze of its own, one the camera’s movement links with the power of this mysterious woman’s gaze—an elaboration of the strategy Hitchcock had employed in The Wrong Man to imply that the painted Jesus has a gaze with comparable power. Thus the shot of Scottie that follows, which seems to present Scottie’s reaction (or nonreaction) to what he is seeing, seems at the same time to represent what this “necklace/eye” is seeing, or conjuring. As Scottie walks, zombielike, toward the camera (but without coming any closer), it is as if this woman’s gaze, relayed by the “necklace/eye,” is drawing him by its hypnotic power, even when the black background is replaced by one that places him in Carlotta’s graveyard. Hitchcock cuts to a shot in which the camera moves toward an open grave. The darkness within the grave looms larger and larger until the frame is again engulfed by blackness.

In this shot the dream alone commands the camera’s attention. But whose dream is it? I am moved to ask this question because the preceding shot of Scottie, which cued us to take the present shot as being from his point of view, began as a representation of the “necklace/eye”’s vision. Our view of the open grave seems to have its source or origin in the mysterious woman’s gaze. Has she by some unnatural art planted her own vision inside Scottie’s dream or raised it from the darkest depths of his soul? Does such a question even make sense? Who or what would this woman have to be to possess such power? I am persuaded that she is the “real” Madeleine Elster. But this is not who Scottie thinks Madeleine Elster is. How could a dead woman Scottie never knew gain entrance into his dream? He cannot have invited her in, since he doesn’t know she ever existed. Unlike vampires, though, ghosts don’t have to wait for an invitation. If this is Madeleine Elster, it is her ghost. Why would this ghost haunt Scottie? Is it because he took no notice of her, failed to keep her safe, did not prevent her from being murdered?

Figure 11.7

Figure 11.8

Figure 11.9

The shot of the open grave also aligns Scottie’s dream with the scene the woman he knew as “Madeleine” described when he pressed her to say what she remembered after awakening from one of her trances. We will soon come to know—or think we know—that “Madeleine” was only acting when she told Scottie she remembered standing before her own freshly dug grave. In the present view of the open grave, Scottie’s dream fuses with that scene he will then believe she believed she remembered.

The moment the camera descends into the open grave, there emerges from the blackness an image that is vertigo-inducing to view. The shot frames Scottie’s disembodied face, staring at the camera, against a receding spiral.

This surrealistic frame strikes me as a kind of inversion of the image in the title sequence of the spiral emerging from the black circle at the center of a woman’s eye. Its ambiguity again elaborates on the ambiguity of the shot in The Wrong Man of Manny’s fractured image in the mirror. Are we seeing what Scottie’s imagination is conjuring, or are we only seeing Scottie in the act of seeing whatever he is seeing in his dream? Is the camera inside, or outside, the dream? And how can Scottie be dreaming, since his eyes are wide open? Is he dreaming of himself dreaming? Is he dreaming of himself dreaming of himself dreaming?

Scottie’s face now disappears, leaving only the vertiginous background. Then the face reappears yet again—this time, it almost fills the screen. The shot that follows begins with the screen yet again engulfed by blackness, as if this emblem of nothingness is what Scottie was envisioning as represented in the previous shot. That Scottie is this blackness is revealed as his stylized, silhouetted figure falls from the region of the camera, whose view he had totally eclipsed, casting the world in shadow. Visually, this figure, which is its own shadow, seems at once inside the world on film and outside looking in, as we are. This effect is underscored by the fact that the lines of the roof form a perfect instance of Hitchcock’s signature //// motif. In Scottie’s nightmare self-image of his body falling, the background marked by the //// abruptly vanishes, giving way not to blackness but to whiteness. Scottie’s shrinking figure is no longer in the world. Is it suspended in infinite space? Or is it a mere shadow, or a black paper cutout, on the flat white surface of the movie screen? His figure’s posture, at once scarecrow-like and Christlike, anticipates Scottie’s posture in the film’s final shot (see fig. 0.7). In that shot Scottie, looking down from the tower from which Judy has just fallen, or jumped, to her death, finds himself suspended as if for all time, as if time itself were suspended. And it is this uncanny premonition of his own fate that makes Scottie sit bolt upright in his bed and stare in terror at the camera. We cannot tell from this shot whether his awakening is real or whether he is only dreaming that he is not still dreaming. The sequence has come full circle.

It is the extraordinary way Hitchcock designs Scottie’s dream sequence (if that is what it is), and Vertigo as a whole, for that matter, that makes possible Chris Marker’s interpretation of the film. It is possible to interpret everything we view from this point on as a continuation of Scottie’s dream. Marker errs only by claiming that in reality Scottie is dreaming everything that happens in the last third of the film. Hitchcock has gone to extraordinary lengths to make this sequence demonstrate that in the world on film there is no reality—at least, if the criterion of reality is that it stands opposed to unreality. In the world on film, all possibilities are equally real and equally unreal. Everything that is, in the projected world, also is not. Everything the projected world is, it also is not.

Figure 11.10

Judy’s Plan

Scottie, like Manny, is an open book to Hitchcock’s camera. His thoughts are legible even when we find ourselves increasingly reluctant to endorse them. The mystery at the core of Vertigo, the mystery that attracts Scottie himself, is not a mystery about him. It is a mystery to him. But it is a mystery the “hard-headed Scot” does everything in his power to explain away. Scottie himself is a mystery to Hitchcock only insofar as he illustrates the fact about being human that it is possible for others to know us better than we know ourselves. The camera’s relationship to the woman projected on the movie screen, in her various guises, is more ambiguous but also more intimate. She is an object of desire to Scottie, to us, and to Hitchcock. Yet she and Hitchcock’s camera are also mysteriously attuned.

I drew the conclusion in “Vertigo: The Unknown Woman in Hitchcock” that this mysterious woman is no less a stand-in for the film’s author than is Gavin Elster, the film’s murderous villain. Hence the title I gave my essay. Yet I had no doubt that this “unknown woman” was known to me. (“I was so much older then,” sang the young Bob Dylan, one of Emerson’s greatest disciples. “I’m younger than that now.”)

I seem always to have known that it cannot be a simple mistake when Judy—saying, “Can’t you see?”—asks Scottie to help her put on her necklace. (Freud was a genius, after all.) I said as much in “The Unknown Woman in Hitchcock.” “The deepest interpretation of Judy’s motivation for ‘staying and lying,’” I wrote, “is that she wishes for Scottie to bring Madeleine back (which means that it is no accident when she puts on the incriminating necklace). Judy wishes for Scottie to lead her to the point at which she can reveal that she is Madeleine—but without losing his love” (230). I understood that “deep down” Judy wished for Scottie to “change” her. But I still assumed, as has every commentator on Vertigo, that in the last third of the film it is Scottie who is leading Judy, not the other way around, hence that putting on the necklace is at most a slip. At least I recognized it as a Freudian slip, one that revealed an unconscious wish for Scottie to know the truth about her.

The thought had not yet dawned on me, however, that Judy might be conscious of harboring such a wish, hence that putting on the necklace might be a deliberate gesture, a step in a plan calculated to make that wish come true. Nor had it dawned on me to ask myself why I resisted questioning the assumption—an assumption, and a resistance, common to all who have written about the film—that Judy could not be conscious of wishing for Scottie to know the truth. Evidently, I believed I knew this woman better than she knows herself. Evidently, I wished to believe this. How could I not have known this about myself? What made me awaken to this truth?

It is vertigo-inducing even to contemplate the possibility that Judy consciously plans for Scottie to discover the necklace. One reason I find this idea so dizzying is that it calls for me to recognize that Hitchcock had deceived me. I trusted him to reveal the border separating what is real from what is not, but he betrayed my trust. Why would Hitchcock do this to me?

“Why me?” is a question Scottie poses (to Judy? to Madeleine? to himself? to whatever God there may be?) on top of the tower after he accuses her of being Gavin Elster’s “very apt pupil” (the pun surely intended by Hitchcock but not by Scottie). “I was the made-to-order witness, wasn’t I?” is his answer to his own question. In my wish to believe that I knew what I really did not know about Judy, about Vertigo, and in my wish to believe that I did not know what I really knew, I was Hitchcock’s made-to-order witness. I was no different from Scottie in Hitchcock’s eyes. I did not wish to believe that of myself—or to believe that of Hitchcock. As the postscript of The Murderous Gaze confesses, I wished to believe—and I did believe—that I was Hitchcock’s “very apt pupil.” As I am writing these words, I wish to believe—and I do believe—that I was blind, but now I see.

It is also vertigo-inducing to contemplate the possibility that in Shadow of a Doubt Uncle Charlie’s plan is not to kill Young Charlie but for her to kill him. Or that it is Norman, not the mother who is her son’s creation, as the smug psychiatrist believes, who grins at the camera at the end of Psycho. Yet in The Murderous Gaze I took those possibilities seriously, just as in Contesting Tears Cavell took seriously the vertigo-inducing possibility that Stella Dallas deliberately makes a spectacle of herself at the soda fountain, that she is already carrying out a plan to free her daughter—and herself—to accept the necessity of their separation. And yet, until now I did not even consider the possibility that the woman in Vertigo knows herself better than I knew her—and better than I knew myself. Like Scottie, I loved this woman and wished to go on loving her. I did not wish to think that I was her made-to-order witness.

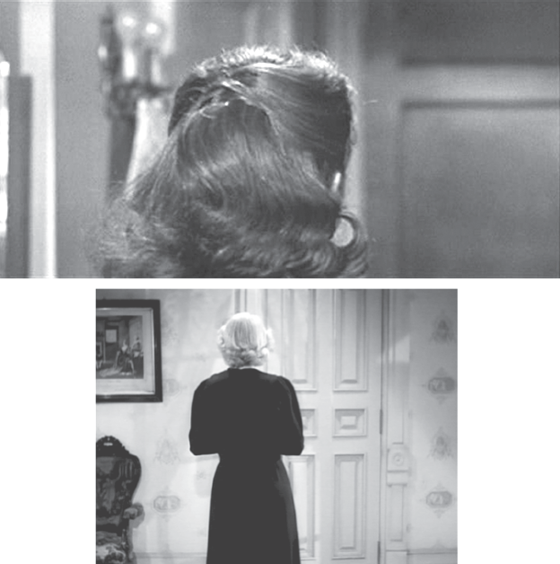

It is Judy’s letter to Scottie, together with the flashback that shows us the “true story,” à la The Wrong Man, that sets us up to believe, wrongly, that we always know what Judy is thinking. The passage is prefaced by the moment when Scottie, who has just walked back into her life, exits her room in the Empire Hotel and Hitchcock’s camera pans to Judy and then holds on her, framed from behind, staring at the closed door, precisely the way King Vidor’s camera holds on Stella Dallas after Stephen departs with their daughter, Laurel.

Figure 11.11

In this framing, the woman and Hitchcock’s camera are in complicity, as they were that night at Ernie’s when Scottie, believing she was Gavin Elster’s wife, Madeleine, whom he had been hired to follow, fell in love with her at first sight. Deliberately, but pretending it was only by chance, “Madeleine” had “happened” to pass close to him, “happened” to pause, and “happened” to present her profile for him to view, enabling him to drink in her intoxicating beauty. The present shot so emphatically hits us over the head with the fact that Judy’s hair is different from “Madeleine”’s that it distracts us from registering its deeper revelation, which is that we are being refused access to what this woman is feeling or thinking.

Figure 11.12

A few moments later, the flashback proper is initiated by another close-up of Judy, this time staring toward the camera, a signal that the views to follow will grant us access to her inner reality.

Scottie, in his dream, seemed unaware of the source of the images assaulting him. Judy, by contrast, seems to be marshaling the images the camera presents to us, authorizing the camera’s presentation, in effect. This flashback is designed to secure our trust in Judy—and in Hitchcock’s camera. We trust that Judy’s letter, which she reads out loud in voice-over as she is writing it, proves that she loved Scottie, that she still loves him, and that if she “had the nerve,” she would “stay and lie” in the hope of making him “forget the other, forget the past” and love her, as she puts it, “as I am, for myself.” And we are moved when she admits to herself—by now, she has stopped writing; what began as a letter to Scottie has become an interior monologue—that she does not know whether she has the nerve to try.

Having confessed this self-doubt, still in close-up, Judy, expressionless, stares again in the direction of the camera, this time without the suggestion of meeting its gaze. Still facing the camera, her gaze still averted, she rises solemnly, her movement synchronized with the camera’s as it pulls back. Momentarily, she is eclipsed by a table lamp, before she is framed by the lamp on the left of the screen and a mirror on the right.

Figure 11.13

Now steadfastly meeting the camera’s gaze, acknowledging its power to bear witness, she purposefully—perhaps there is a trace of violence in her gesture—tears the letter to pieces. Like the “right” wrong man, she has come to a decision. Whatever the risk, she will “stay and lie” and prove she has the nerve to make Scottie love her “as she is, for herself.” We silently applaud her.

This passage sets us up to think that we know what Judy is thinking. We have her own testimony as evidence. Yet at the decisive moment, she is silent, absorbed in her private thoughts. The camera, which moments before had revealed Judy’s vision of the past, now refrains from revealing her vision of the future. Lacking her clairvoyance, we have no access to her thoughts at this all-important moment. And yet we think we know what she is thinking. We think we know what she means by “staying and lying”; what she thinks it means for Scottie to love her “as she is, for herself”; and what she thinks her “self” is—what it is “for herself.”

In “Vertigo: The Unknown Woman in Hitchcock,” I wrote, “When Judy writes the note she never sends to Scottie…she contemplates ‘staying and lying’ and making him love her ‘for herself.’…She may think that the Judy persona—Judy’s way of dressing, making herself up, carrying herself, speaking—is her self.…Yet…once she is transfigured into Madeleine, there is no bringing Judy back. She can act the part of Judy only by repressing the Madeleine within her, only by theatricalizing herself” (230).

I understood that “Judy,” no less than “Madeleine,” is a role this woman is playing (just as this woman herself, in both guises, is a role played by the actress we know as “Kim Novak”). I also understood that the fact she has made these roles her own means that both “Judy” and “Madeleine,” at once her creations and her incarnations, are expressions of who she is. But I assumed that these were facts I knew about her that she didn’t know about herself. I continued to cling to the assumption—as all critics have done, as Hitchcock sets us up to do—that in wishing for Scottie to love her “as she is, for herself,” she was wishing for him to love “Judy,” that slightly slutty dark-haired hard-luck story who wears too much makeup and speaks not in Madeleine’s near-British English but rather pronounces “Salinas, Kansas” with a whiny, exaggeratedly lower-class midwestern twang. (In her voice-over Kim Novak reads Judy’s letter in a voice more neutral, more natural, than either of those voices.)

The thought had not yet dawned on me that this woman wishes for Scottie to love her as the actress she is, not the “Judy” who is one of her roles—a role that so perfectly denies her “inner Madeleine” that she must have created it for that purpose. I am not claiming that in the world of Vertigo the reality is that Judy is always acting. My claim is that Hitchcock designs the film so that every moment sustains this as a possibility. Again, it is Hitchcock’s understanding that in the world on film there is no reality as opposed to unreality. All possibilities are equally real, all equally unreal. I might add that we don’t even know that “Judy” and “Madeleine” are this woman’s only identities. She keeps as many suits and dresses in her closet as Marnie. For all we know, each is a costume, a memento of one of her roles. We don’t even know that “Judy Barton” is her real name. That is what it says on her Kansas drivers license, but for all we know she has as many phony licenses as Marnie, or as, in North by Northwest, Vandamm’s cohort Leonard assumes that George Kaplan has when he contemptuously says to Roger, believing him to be that nonexistent decoy agent, “They provide you with such good ones.”

It would seem that Judy (as I will continue to call her) has set herself an impossible goal. How, by lying, can she possibly make Scottie love her “as she is, for herself”? Then again, insofar as she is an actress whose identity cannot be separated from the characters whose roles she has made her own, how can she make Scottie love her “as she is, for herself” except by “lying”? Insofar as she knows that, as an actress, there is nothing she is “for herself,” she possesses the knowledge possessed by the heroines of such “unknown woman” melodramas as Stella Dallas, Now Voyager, and Letter from an Unknown Woman (all films intimately related to Vertigo). It is the knowledge, the self-knowledge, that, as Cavell puts it, their identities are ironic. Judy knows, as those women do, that her “self” is not fixed; that everything she is, she is capable of not being; that in the condition in which she finds herself—Emerson thinks of this as the human condition—she stands in need of creation.

Terrified of death, longing to become someone “for herself,” she stakes her quest for selfhood on winning Scottie’s love. Why Scottie? Both as “Judy” and as “Madeleine,” she loves this man. As she writes in her letter, she wants him to find “peace of mind.” Unless she saves him, she cannot be saved. If she lets him “change” her so he can love her as “Madeleine” again, or, for that matter, if he falls in love with “Judy” and falls out of love with “Madeleine,” she would not win his forgiveness, apart from which she cannot be saved. She cannot tell him the truth without making him stop loving her, but his love cannot save her unless he learns the truth. Neither of them are saved if Scottie loves “Madeleine” but not “Judy,” or “Judy” but not “Madeleine,” or even if he loves both but without recognizing that they are “positively the same dame,” as Muggsy (William Demarest) puts it in The Lady Eve. Only if Scottie finds “Madeleine” in “Judy” and “Judy” in “Madeleine” can his love heal the rift in her soul and enable her to be reborn, to take a step in the direction of her unattained but attainable self. How can she make this happen?

Judy’s unfinished letter to Scottie began, “And so you’ve found me.” Scottie’s finding her is one of those “accidents” Hitchcock is wont to arrange to bring reality and fantasy into alignment. But I view this “accident” as also arranged by Judy. It is the first step in her plan.

Scottie is standing in front of the flower shop where he saw “Madeleine” buy the nosegay—he haunts all the places “Madeleine” used to frequent—when Judy “happens” to walk by, chatting with friends. She “happens” to pause in full view of Scottie, “happens” not to see him; “happens” to turn her face so that he views her in profile, exactly as “Madeleine” had pretended she hadn’t deliberately done that fateful evening at Ernie’s. After Scottie follows her to the Empire Hotel, the camera slowly tilts to an upper-floor window she “happens” to open. Then she “happens” to stand framed in that window. Scottie now “happens” to know exactly where to find her.

Even if we think it is only by chance that Scottie finds her, Judy—like Félicie in Eric Rohmer’s A Tale of Winter—gives the man she loves every chance of finding her by chance. Unlike Rohmer’s heroine, but very much like Paula (Greer Garson) in Random Harvest (which I suspect provided the inspiration for Vertigo’s telltale necklace), Judy knows all along where to find the man she loves. But her plan is to let herself be found.

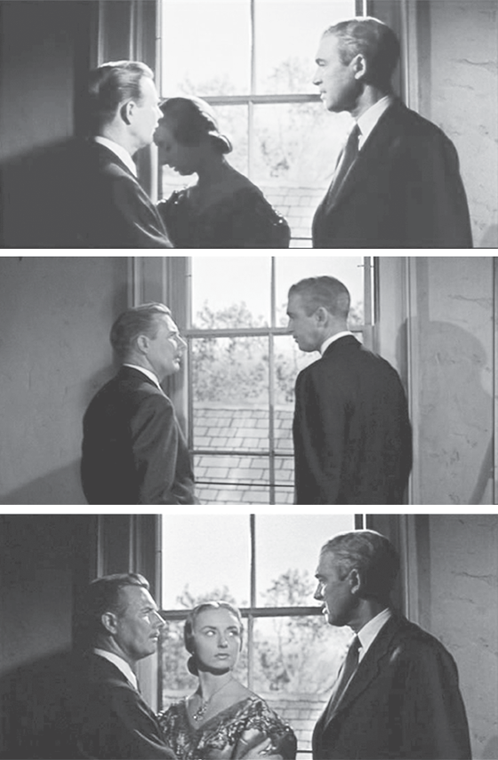

Figure 11.14

Judy’s next step is to lead Scottie to believe that changing her is his idea, not hers. When she finally gives in, as Scottie thinks of it, and allows herself to become “Madeleine” in his eyes, they kiss. Hitchcock expresses Scottie’s rapture by that celebrated camera movement in which the background changes from Judy’s hotel room to the livery stable where they had kissed before. The camera is registering a change in Scottie’s subjective experience, we take it, but one he has not (yet) consciously registered. He does not literally see or even imagine the change in his surroundings the camera presents to us. We know, or think we know, that Scottie hasn’t really gone anywhere. He has been transported only metaphorically. What has transported him is this woman’s kiss. (He is not a necrophiliac, as some commentators have suggested. Chris Marker is on target when he insists that in this kiss Judy is anything but dead to Scottie; she is “Madeleine” very much alive.)

Figure 11.15

But then Scottie opens his eyes and turns his face almost to the camera, so we see his perplexed expression. We also see that he is hiding his perplexity from the woman in his arms.

Our impression is that Scottie is seeing the change in his surroundings that we are seeing, and is at a loss to explain it, just as he is at a loss to explain how it can be that this woman not only looks like “Madeleine” but also kisses like her. But what causes the background to change? Scottie’s perplexity makes clear that it is not his doing. Of course, we can say that it is Hitchcock’s camera that effects the change. But it does so by way of registering a change in Scottie’s subjective experience, the fact that he has been transported. And it is Judy who makes that happen—deliberately, I am suggesting—by the magic of her kiss.

Like a man awakening from a pleasurable dream and willing himself back to sleep, perchance to continue the dream, Scottie abandons himself to Judy’s embrace, choosing not to question the miracle, or black magic, that has brought his love back from the dead. I view Scottie’s fateful decision, too, as internal to Judy’s plan. Although the kiss resumes, it is not the same as before. The camera’s continuing circling has led it to frame Judy from behind. We no longer see her face, only the spiral twist of her hair, an image that will be echoed, uncannily, in Psycho.

Figure 11.16

Judy is no longer the kisser but the kissee. Neither resisting nor responding, like Marnie in Mark’s arms on their honeymoon cruise from hell, she has become, visually, a lifeless body. And this change in the image does not register a change in Scottie’s subjective experience. That he does not feel he is kissing a corpse is confirmed, I take it, when after the fadeout that signifies that they have sex, Scottie relates to Judy—who expresses the wish for a “big, juicy steak”—in a way that makes clear he sees her as full of life. If Hitchcock’s camera registers anyone’s subjectivity, it is Judy’s, when it intimates that Scottie’s kiss drains her of life. Understandably, she feels deadened in Scottie’s arms, for he hasn’t yet come to see her as she is, “for herself.” This kiss takes her closer to her goal, but it does not get her there. She has yet to take the most dangerous step. She takes it when she asks Scottie, seemingly in all innocence, to help her put on her necklace—Carlotta’s necklace, “Madeleine”’s necklace. The necklace moves him to open his eyes, as it had in his dream.

Once Scottie knows—or can no longer deny to himself that he knows—that this woman is “Madeleine” or, rather, that the “Madeleine” he loved never existed, Judy “lets” him return her to the scene of the crime and drag her to the top of the tower, enraged enough to kill her. All this is part of her plan. When she declares her love for him, falls into his arms and pleads with him to keep her safe, he says, “It’s too late, there’s no bringing her back,” but does not resist her embrace. And he responds to her “Please…” by kissing her with overwhelming passion. And this kiss completes Judy’s plan, I take it. Everything has unfolded as she had scripted it. All is fulfilled. She has led Scottie to this point at which he forgives her, and himself, and loves her unconditionally. For Scottie this kiss is forever. Then why is it the kiss of death for Judy?

When in The Wrong Man Manny visits Rose in the hospital to bring the glad tidings that the police have caught the man who committed the crimes of which he was accused and that their nightmare is over, she says, “That’s fine for you,” rebuking him for assuming that her life revolved around his. In “The Unknown Woman in Hitchcock” I viewed the ending of Vertigo as such a rebuke to Scottie. Yes, holding this woman in his arms is his dream come true. But how can it be a step in the direction of her unattained but attainable self for her to find herself in the embrace of a man for whom it makes no difference who or what she is, whether she is “Judy,” a human being of flesh and blood; “Madeleine,” a woman who never existed; or even the ghost of “Carlotta,” a madwoman who took her own life?

I now have a more compassionate view of Scottie. When Judy declares her love and pleads with him to keep her safe, he rebukes himself for having been, like Devlin in Notorious, a “fat-headed guy full of pain” who had been so absorbed in his own feelings that he had failed, until this moment, to recognize who she is, “for herself.” For Scottie this kiss is not like the kiss in Judy’s hotel room. His vertigo is gone. He holds in his arms the key to the mystery. It is not, as I had thought, a matter of indifference to him who or what she is. Judy is now Madeleine, and Madeleine Judy, in his eyes. He forgives her for the suffering she caused him. What more is there for Judy to ask of Scottie? Nothing more, as there is nothing more for him to ask of her. Like the couple at the end of a remarriage comedy, he has forgiven her, she has forgiven him, and they have both forgiven themselves. And if they have forgiven each other, what standing have we—or Hitchcock—to rebuke one on the other’s behalf?

Then why does Judy have to die?

Madeleine’s Revenge

When I wrote “The Unknown Woman in Hitchcock,” I believed that Judy chooses to die when she recognizes that Scottie’s kiss has changed nothing, that in his eyes she is still nothing “for herself.” If with this kiss Scottie does acknowledge her, as I now believe, who, or what, kills her? Why does she pull away from Scottie’s kiss, as she had at the livery stable, her gaze drawn in the direction of the camera? That what provokes this is not something Judy literally sees when she looks toward the camera is made clear when Hitchcock cuts to a shot, from her point of view, that is devoid of human figures. Only after a moment does a shadowy figure emerge, barely perceptible, out of the blackness.

Judy seems to know what she will see before she literally sees it, as if she imagines this specter before her gaze and the camera, in concert, conjure it into being. When she does see this shadow, her eyes widen. The fact that what she had imagined is real takes her by surprise. That this is not something she has planned is significant, because it implies that if she sees this shadow as Death coming to claim her, as I do not doubt she does, Death is not coming at her bidding. And yet she immediately knows, or thinks she knows, who or what this apparition is. She recognizes it. But how can she recognize this specter unless it had appeared to her before? While in character as “Madeleine,” Judy had described to Scottie a scene she said she remembered in which she stood before what she knew was her freshly dug grave. She now knows in the same way, I take it, what this shadow is—that it is, in effect, her own freshly dug grave. Is it, then, that she really did dream the scene she had only pretended to remember, that she is only now remembering that dream, which has returned to haunt her?

Scottie, not granted her vision (although it is one that he might well have recognized from his own dream), remains absorbed in embracing Judy until with a heartbreaking, “Oh no, no!” she steps back in terror and awe and slips silently out of the frame. Only when it is too late does Scottie turn, and we hear a woman’s offscreen voice say, “I heard voices.” There is a chilling scream and Scottie wheels around in horror. As Hitchcock films this scene, we do not know whether in her terror Judy accidentally steps over the edge or whether she deliberately jumps. Does she scream as she is falling because she wants to live or because she has chosen to die but finds herself terrified as the void is about to engulf her?

Figure 11.17

Judy’s scream still reverberating, the silhouetted figure steps into the light. It is a nun. And she is looking straight into the camera.

Crossing herself, the nun intones, “God have mercy,” and begins tugging on the bell rope, ringing down the final curtain on Hitchcock’s most disturbing film.

In discussing the shot of the open grave in the dream sequence, I was motivated to ask whose dream this really was. The vision of the open grave seems to have its source, or origin, in the gaze of the woman I took to be the ghost of Madeleine Elster. And I found myself wondering whether Madeleine’s ghost, with the complicity of Hitchcock’s camera, was the author of that vision. I now find myself wondering whether Madeleine’s ghost—again with the complicity of Hitchcock’s camera—is the author, as well, of the vision that kills Judy.

It hardly seems just for Madeleine’s ghost to make Judy die screaming while letting her deceitful husband get away with murder. But Judy is vulnerable to being haunted, as Gavin Elster is not, because she is already haunted, as Scottie is. I am not suggesting that Judy sees the shadow that frightens her as the ghost of Madeleine Elster. Judy sees it as a vision of her own death, the way Scottie sees his death in his vision of the open grave. If the vision of her death Judy sees when she looks toward Hitchcock’s camera emerges from the depths of her soul, how did it get there in the first place? Has the dead Madeleine somehow conjured it into wakefulness, or planted that vision—perhaps Madeleine’s vision of her own death—in Judy’s soul? That this death-dealing vision metamorphoses into a flesh-and-blood nun suggests that if it is an unnatural art that raises the specter that kills Judy, it is also divine justice that she die. The nun herself is powerless. She can only bear witness, in her faith, that God’s will has been done.

Judy’s lies to Scottie, like the psychic violence of his efforts to change her, are venial sins. If there is such a thing as a mortal sin, Gavin Elster surely commits one when he murders his wife. As I have argued, in the world on film murder is not forgivable. No living person has the power to forgive the murder of another person. Scottie can forgive Judy for the suffering she caused him, but he has no standing to forgive her for the part she played in the murder of Madeleine Elster.

Do we believe that her complicity in Gavin Elster’s diabolical plot to murder his wife makes Judy guilty of a sin morally equivalent to his? We do not wish to think that she is a murderer. But our judgment must hinge on whether we believe that when she breaks away from Scottie’s kiss at the livery stable, tells him there is something she must do, and runs up the tower, she is sincerely trying to keep the murder from happening, or is still playing her assigned role in Elster’s script. It is internal to Hitchcock’s design of Judy’s flashback, I take it, that it does not settle this question. Nor is it settled by her later telling Scottie that she tried to stop it. No matter how well she knows herself, even she does not know the answer to the question. That is something only God can know.

A few pages ago I was moved to ask myself, as I often have, why Judy has to die. But that is a prejudicial question. It presupposes that Judy’s death is necessary, that Hitchcock has no choice but to kill her, that it is not in his power to keep her safe. If her death has no necessity to it, it would mean that Hitchcock chose to kill her, that like the arch misogynist some mistakenly take him to be, he wished for Judy to die. Would that make the creation of Vertigo the moral equivalent of murder?

What, if anything, legitimizes killing? How, if at all, does the act of killing change the person who performs that act? As we have seen, these are questions to which the Nazi menace gave special urgency in Hitchcock’s British films of the late 1930s, such as Secret Agent, Sabotage, and The Lady Vanishes, and the films he made in America during the Second World War, such as Shadow of a Doubt and Lifeboat, and in the war’s immediate aftermath, such as Notorious and Rope. But every Hitchcock thriller has its own way of posing and addressing these questions, and of thinking through their implications for the art of pure cinema of which Hitchcock was both master and slave.

If there were no Gavin Elster in the world of Vertigo, Judy would not have to die. But if there were no Gavin Elster, there would be no Vertigo. Elster is Hitchcock’s accomplice in artistic creation. But Hitchcock is Elster’s accomplice in murder. Madeleine has to be murdered for Vertigo to be created. Judy, too, has to die.

And what of Madeleine Elster? There would be no Vertigo unless she were murdered. Yet except for her appearance in those two pivotal shots in Scottie’s dream sequence, Hitchcock’s camera takes no notice of her. The film’s author seems as indifferent to Madeleine’s fate as her murderer is, as Judy is, as Scottie is, as we are. When Judy looks toward Hitchcock’s camera and sees the figure of Death come to claim her, it has finally dawned on me, this death-dealing vision is the murdered woman’s revenge. If Hitchcock is Gavin Elster’s accomplice in Madeleine’s murder, he is no less an accomplice in Madeleine’s revenge against Judy. But Judy’s death is Madeleine’s revenge against Hitchcock as well. Judy’s fall forces the film’s author to recognize the limits of his own power—the dark fact that he could not keep Judy safe even though he loved her—and the murderousness of his unnatural art—the even darker fact that Hitchcock killed Judy not only because he had to but because he wished to. Hitchcock wished for this woman he loved to die so that his most perfect work of art could be born.

I am aware, of course, that Madeleine Elster—not to mention her ghost—has no real existence apart from the world of Vertigo. But what kind of existence is that? In the world on film, the opposition between the natural and the supernatural breaks down. The camera represents a supernatural agency to the denizens of a film’s world. For them, the film’s author and viewers alike are ghosts. And the camera’s subjects, fixed and projected onto the screen, are suspended between death and life.

I am also aware that Alfred Hitchcock was a human being of (more than ample) flesh and blood, that unlike Madeleine or Judy, this man really existed. But even during his lifetime his existence was a double one. Viewed from the perspective of the world on film, he was—is—a ghost. Now that he is dead, it is only as a ghost that he is real to us, only through the medium of film that he speaks to us. In reality, of course, no human being dies when Judy jumps or falls from the tower. In reality, Hitchcock was no murderer. Then again, in Hitchcock’s understanding, the medium of film, by its very nature, mysteriously overcomes or transcends the opposition between what is objectively real and what is real only subjectively. The world on film is real, but it is not reality. It is reality transformed by the medium of film.

An Awakening for Hitchcock

In Rope, as we have seen, Brandon makes a distinction between “talking”—mere words—and “living.” When Guy, in Strangers on a Train, says—and means—that he could kill his scheming wife, that is “talking.” When Bruno murders her, that is “living.” Does morality have to do only with “living” and not also with “talking”? When Herb and Joe, in Shadow of a Doubt, “relax” by talking about murdering people, does that have nothing to do with living?

In authoring his films, Hitchcock envisions characters who commit murder. But he also envisions killings he performs himself in his capacity as author. Again, in reality Hitchcock is no murderer. Yet on film there is no intrinsic difference between what is objectively real and what is real only subjectively. As I have said, that is what makes possible Hitchcock’s signature practice of employing his powers as author to make his characters’ innermost wishes—wishes they are not even conscious of harboring—“magically” come true. Indeed, it is Hitchcock’s practice to throw back at his characters not only the words they speak but also their thoughts and their dreams. Are we responsible for our dreams? Are we free to dream what we wish? If Freud is right, we are free only to dream what we wish. If the world on film overcomes or transcends the opposition between fantasy and reality, does it also overcome or transcend the opposition between “talking” and “living”?

I wish to believe—and I do believe—that there is a difference, morally, between Gavin Elster and Hitchcock. I wish to believe—and I do believe—that Hitchcock was not indifferent to Judy’s fate, that he loved her as much as Scottie does. Vertigo is a tragedy because Scottie’s love fails to keep Judy safe. The tragedy is also Hitchcock’s. Not only does he fail to keep this woman safe, but he takes it upon himself to kill her.

As we have seen, Hitchcock’s lifelong attraction to Oscar Wilde’s principle that each man kills the thing he loves, which in its negation of all hope for change is not only un-Emersonian but anti-Emersonian, coexisted tensely and uneasily with his attraction to the Emersonian moral outlook embraced by the comedy of remarriage. After Vertigo, how can he continue to author Hitchcock thrillers, if doing so requires him to kill the things he loves—and to love the things he kills? Is that the kind of person, the kind of artist, Hitchcock wishes to be? Taking to heart the tragedy of Vertigo, Hitchcock acknowledges the need to change.