After North by Northwest and Psycho Hitchcock was riding high, artistically and commercially. He planned to follow up these successes by wooing Grace Kelly out of retirement and pairing her with Cary Grant in an adaptation of Winston Graham’s novel Marnie. When the people of Monaco, in a referendum, expressed the wish that their Princess Grace not return to the screen (and certainly not as a psychologically disturbed kleptomaniac), Hitchcock signed Tippi Hedren, a model his wife had noticed in a television commercial, to an exclusive contract. Thanks to his friend Lew Wasserman, Hitchcock was offered an ownership share in Universal, and it seemed an ideal setup for the last chapter of his career. Deferring Marnie, he chose as his first film at his new studio home The Birds, based on a Daphne Du Maurier story (as was Rebecca, his first film in what was to become his new home, America).

Production of The Birds was challenging—perhaps too challenging. “Not enough story, too many birds,” Hitchcock summed up the film, too harshly but not entirely inaccurately.1 On the whole I find the bird attacks, heavily reliant on special effects, to be extraordinary technical achievements on the part of his gifted and dedicated collaborators but less effective than some of the less spectacular sequences; for example, the quietly understated passage in which Melanie (Tippi Hedren) sits smoking on a schoolyard bench while waiting for the children to be sent out for recess. We see, as she does not, that crows, one by one, are gathering on the monkey bars behind her back. But when her eyes follow a single bird and the camera follows her gaze to a framing that reveals crows occupying every possible perch on the once bare monkey bars, we are as shocked as she is. We are struck by their sheer number but also by their eerie stillness, which continues until they fly off as one, in a sonic burst of beating wings, just as the children leave the schoolroom. The immediate attack on the schoolchildren—an impressive montage that was far more difficult, technically—is almost an anticlimax.

Figure 14.1

Yet the single greatest shot in The Birds is the one that posed perhaps the greatest technical challenge: the “bird’s eye” view of the gas station in flames, the camera occupying an impossible position alongside the soaring seagulls, as if a bird of their feather.

Figure 14.2

Ordinarily, when the camera calls attention to itself in a Hitchcock thriller, the film’s author is showing his hand, declaring that he is the deity who presides over the world of the film. This shot is different. Here, the camera, surveying its domain from a great height, unafraid of falling, seems beyond the control, or ken, of a merely human author. But it is not God’s instrument, either, as in The Wrong Man. The birds that oversee this world are just birds, this shot implies. Creatures of their appetites, they exist within nature. This condition they have in common with human beings. But they are not human.

No doubt emboldened and challenged by the films of Truffaut, Godard, Chabrol, Rohmer, and the other young French critics-turned-directors who were fervent in their admiration of his films, Hitchcock experiments in The Birds with cinematic devices that at times give it a bit of the feel of a nouvelle vague film. He uses jump cuts, for example, to convey the discovery, by Lydia, Mitch’s widowed mother (Jessica Tandy), at the neighboring Fawcett farm, of the body of her friend, his eyes pecked out.

The Birds’ narrative, too, has something of the feel of a European art film. I am thinking, for example, of the film’s refusal to attribute to the birds a clear motive for their violent attacks on Bodega Bay’s human inhabitants (although the film repeatedly intimates that, like the camera, the birds have a special bond with Melanie); its refusal to provide a “scientific” explanation (on the order of the radioactive fallout science fiction films of the 1950s were wont to cite as causing the strange metamorphoses of ants, mantises, and the like into humongous monsters) for the birds’ changed behavior (although the film keeps reminding us of the outrages against nature that humans unthinkingly perform every day); and, especially, its unresolved conclusion, from which the conventional “The End” is pointedly withheld.

Figure 14.3

This ending offers us no assurance that Melanie, in shock after the birds’ mass assault on her, will ever be herself again. Mitch (Rod Taylor) does all he can, but no man has the power to rescue this woman. Nor are we given any assurance that the birds, having ravaged Melanie, have had their fill of violence, that the cluster of attacks was a localized occurrence, or that humans can safely go on, as before, eating fried chicken and having little regard for our fine-feathered friends—or for each other.

All Hitchcock’s films are open to allegorical interpretation, but The Birds is unique in openly presenting itself as an allegory. How can we not ask ourselves what those birds represent and what they really want (a variant of Freud’s famous question about what women want)? And the question “What do the birds want?” takes on special urgency because the ending precludes our taking the projected world to be a “private island,” a place separated from our world by the safety curtain of the movie screen, a place where we can escape from the real conditions of our existence. Like Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’avventura (1960), The Birds implies that it means more than it literally says. In the film’s overt claim to profundity, too, I sense that Hitchcock was emboldened and challenged by New Wave films like Jules et Jim (François Truffaut, 1962) and Vivre sa vie (Jean-Luc Godard, 1962), made by the young French cineastes who first began to plumb his work’s previously unsuspected depths.

What I value most in The Birds, however, are the down-to-earth, human moments—such as every moment Jessica Tandy or Suzanne Pleshette is on the screen—that reveal its characters’ humanity with an emotional directness unprecedented in Hitchcock’s work. The camera, caucusing with the birds, not the humans, achieves a separation from the film’s merely human author by means of a strategy very different from the one he employed in The Wrong Man. Detached from Hitchcock’s ego, at least rhetorically, the camera is freed from the rancor that afflicts all human beings. Acknowledging that he is the servant, not the master, of the art of pure cinema, in this film Hitchcock does not claim personal possession of the camera, does not strive to impose his will over the film’s world. In The Birds the camera goes a little crazy sometimes (to paraphrase Norman Bates, who, as usual, knows whereof he speaks). But it is also freed, as never before in Hitchcock’s work, to allow its human subjects the freedom to reveal their own humanity.

I am not suggesting that in earlier Hitchcock films the camera’s subjects are never movingly revealed. In Rebecca, for example, when the Joan Fontaine character descends Manderley’s grand staircase in that gown and preposterous hat, her face reveals to us what she is trying to hide from her husband, Maxim, her desperate longing for his acceptance. Or in Shadow of a Doubt, when Young Charlie’s mother breaks down, in full view of family and friends, after her brother, Charles, announces that he is leaving town. Or in Vertigo, when Scottie points out to Midge that she is the one who had broken off their engagement, and a cut to an uncomfortably close high-angle shot reveals to us the pain she is trying to hide. At those moments, however, the camera exposes the vulnerability of subjects who are trying to mask their thoughts and feelings. But when Mitch’s ex-girlfriend Annie (Suzanne Pleshette) offers friendly advice to Melanie, her rival, or when Lydia, Mitch’s mother, confides her fears to Melanie, what the camera captures is what these characters openly reveal of themselves.

Lydia revises humanely the stereotype of the monstrous mother that plays a central (if ambiguous) role in Psycho (and nowhere else in Hitchcock’s work). Annie characterizes Lydia, not unsympathetically, as fearing that Melanie will give her son the love she has never given him. No woman played by Jessica Tandy can be a monster, but Annie understands Lydia’s fear to be a source of Mitch’s resistance to committing himself to another woman. Annie’s characterization rings true, and she offers it as a friendly gesture. Lydia is so different from her own mother that Melanie is genuinely interested in understanding her. Melanie and Lydia both recognize that they are in competition for Mitch’s love. Yet they develop respect, even affection, for each other.

In the course of The Birds we come to appreciate Mitch for his honorable efforts to balance his career and his responsibilities toward his family, which require him to help raise his younger sister and minister to the emotional needs of a mother who sees him as a sorry substitute for her dead husband. As the family braces for the birds’ attack on their home, Lydia makes it all too clear to Mitch that she doesn’t see him as his father’s equal when she blurts out, “If only your father were here!” Rod Taylor isn’t Cary Grant’s equal, either. Who is? However, Taylor’s rugged features, physical strength, and thoughtful demeanor make him a plausible romantic hero, if a somewhat wooden and humorless one.

In Notorious and North by Northwest a character played by Cary Grant rescues the woman he loves but only after his actions have placed her in jeopardy. In the world of The Birds no man has the power to rescue Melanie, if only because no man places her in danger. Mitch does everything that can reasonably be asked of a man to keep his mother and young sister—and Melanie—safe. Nonetheless, when a rustling awakens Melanie, she sees that Mitch is asleep, exhausted by his labors. Whether in reality or in her dream, the birds are calling Melanie. As if entranced, she walks quietly to the stairs, lighting her way with a lantern, ignoring the warning signaled by the //// motif formed by the banister of the staircase.

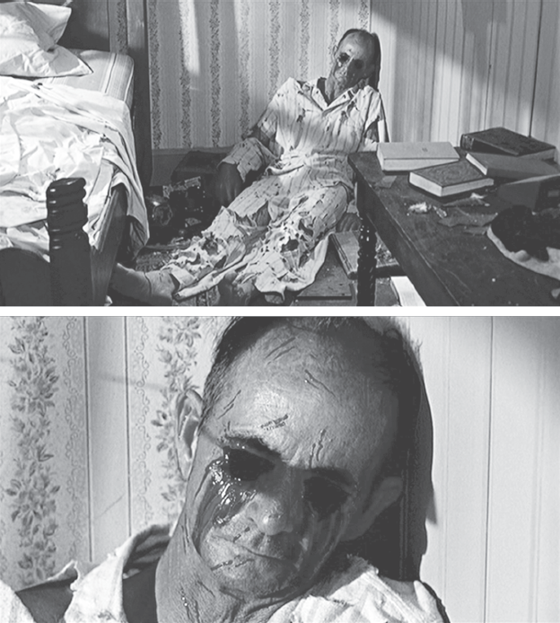

Figure 14.4

Melanie ascends the stairs to the attic, even as everyone in the theater is silently screaming, “No! Don’t go up there!” Melanie must sense, as we do, that the birds are waiting for her. Why else would they have called to her? But why have they singled her out? Why does only she hear their call? Why does she answer it? At the top of the stairs Melanie’s hand reaches slowly for the doorknob but hesitates. A cut to her face conveys that she senses that she is faced with a momentous decision.

Evan Hunter, the film’s screenwriter, has expressed his understanding that when Melanie enters the attic, it is an act of self-sacrifice. Hitchcock’s understanding, I believe, is deeper and more disquieting. At the end of F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), a woman characterized by an intertitle as “pure of heart” offers her life’s blood to the vampire, putting an end to the contagion of death. Without denying the nobility of her gesture, Murnau’s camera reveals that this woman, for all her “purity,” desires the vampire no less than the vampire desires her. In responding to the birds’ call—in ascending the stairs, entering the attic, and even offering her body to the birds to do with as they desire—Melanie, too, however pure of heart, is driven by desire—a desire she believes, not wrongly, that no man can satisfy. What does she desire of the birds? What does she believe they desire of her?

Whether it resides inside her world or outside it, Melanie senses, I take it, the presence of a mysterious “something” that rules the roost. Something that is not human—something uncannily linked to the camera—had called seductively to her, knowing she would be drawn by this call, the way in Vertigo Madeleine, or, rather, Judy, is drawn to the ghostly spirit of Carlotta Valdes, forever searching for the daughter cruelly taken from her. But whatever Melanie may be imagining, she is utterly unprepared for the sustained ferocity of the birds’ attack—as Tippi Hedren was unprepared for the ordeal of filming this sequence (no one had informed her that for days on end live birds were going to be thrown at her from the region behind the camera).

It is only from a scene that Hitchcock took the unusual step of writing himself—he inserted it into Evan Hunter’s screenplay although Hunter thought it was stupid and added nothing to the film—that we learn that Melanie’s mother had deserted the family when her daughter was a young girl. In Hitchcock’s mind, but evidently not in Hunter’s, it is one of the defining features of Melanie’s character that she is a woman who has never known a mother’s love. In the scene Hitchcock wrote, Melanie asks Mitch, in light of his difficult relationship with his own mother, whether it might be better not to know a mother’s love. He answers thoughtfully, but only after a pause almost as long as Jack Benny’s when a mugger says to him “Your money or your life,” that it is better to be loved.

The Birds dwells more on Mitch’s fatherless family than Melanie’s motherless one, but Hitchcock’s interest in Melanie is deeper than his interest in Mitch, his films’ interest in mothers deeper than their interest in fathers. Her knowledge that her mother abandoned her gives Melanie a personal interest in learning something about a mother’s love that her own experience has not taught her. The scene Hitchcock scripted illuminates Melanie’s otherwise inexplicable decision to walk into that attic. Perhaps she hears, in the birds’ quiet call, the call of Mother Nature herself, the voice of the mother whose love she has never known.

The scene also underscores the thought-provoking, emotionally resonant connections between Vertigo and The Birds, and between The Birds and Marnie. Carlotta Valdes does not abandon her daughter; in a bygone world in which men had the power and freedom to do such things, her daughter was taken from her. Marnie’s mother (Louise Latham), too, never abandons her daughter. Indeed, she loves Marnie so much that she sacrifices mightily for her sake. Yet Marnie grows to adulthood not knowing that her mother loves her, hence not knowing from her own experience whether a mother’s love, for which she longs, is worth knowing. The Birds and especially Marnie are Hitchcock’s most heartfelt films, and this question helps bind them together.

When Hitchcock released The Birds, many viewers were disappointed, as I have said, that the film did not out-Psycho Psycho. The world of The Birds is not loveless, like the world of Psycho. Nor does love fall victim, as in Vertigo, to a villain’s sinister machinations. In The Birds there are no villains. All the human characters earn our sympathy. The birds kill, but they are not murderers. Far more than earlier Hitchcock films, The Birds conveys a profound sense that it is human nature to hunger for love but that love is so painful, our appetite for it so voracious, that it is also human nature to avoid loving.

In North by Northwest Hitchcock grants Roger and Eve their wishes; Roger rescues Eve, their romantic dreams come true, and love triumphs. In The Birds all the adult characters we care about are too scarred by life, too wounded, for their romantic dreams to have survived intact. The only character who still believes that dreams can come true is Cathy (Veronica Cartwright), Mitch’s young sister, who insists, when the little family group is about to drive off into an unknown, perilous future, that they not abandon the pair of lovebirds that were Melanie’s birthday gift to her. In his capacity as author, Hitchcock still possesses the power he has always had to preside over “accidents” within the projected world. He still possesses the power to grant wishes, to make characters’ dreams (and nightmares) “magically” come true. But in a world in which human beings have turned against nature, have turned nature against itself, a world in which we no longer harbor romantic dreams or believe in them, no longer know how to wish or what we really wish for, Hitchcock’s powers as author no longer guarantee that he can reward with love characters he loves and who are worthy of love.