In The Murderous Gaze I attended to five Hitchcock films, and to the experience of viewing them, with an unprecedented degree and kind of attention. I said then, and I am saying now: Hitchcock films are designed to teach us how to think about the way they think. And this, as I now understand, is a feature they share with Emerson’s essays. Hitchcock’s films, like Emerson’s essays, have something to offer everyone—they were meant to be, and were, popular. And yet the more closely we attend to them, the deeper they reveal themselves to be. They were designed to teach us how, as films, they express their thoughts by their “moods of faces and motions and settings, in their double existence as transient and as permanent.”1

It is because Hitchcock’s films and Emerson’s essays have such a pedagogical and self-reflective dimension that what Cavell calls “self-images” are everywhere to be found in them. As we have seen, Hitchcock’s signature motifs, which declare his authorship, serve as invocations of the movie screen, the film frame, the camera lens, and so on. They are precisely analogous to what Cavell calls Emerson’s “master tones,”2 the philosophically charged words, which at one level refer to the writing itself, and which recur in Emerson’s writings within each essay and from essay to essay, their occurrences meant to resonate meaningfully with each other.

Writing about the final paragraph of “Experience,” for example, Cavell singles out a number of such words, realize and world among them. When Emerson concludes his essay by noting the discrepancy between the world he “thinks” and the everyday world with which he converses “in the city and in the farms,” he poses the question, “Why not realize your world?”3 It is precisely the aspiration of “Experience,” as Cavell reads it, to “realize” the “world” its author “thinks.” (This is the aspiration of Cavell’s philosophical writings as well.)

At the end of his own essay about Emerson’s essay, Cavell revisits the question with which “Experience” begins: “Where do we find ourselves?” Having followed the essay’s thinking from beginning to end, Cavell finds that the experience of reading “Experience” has taught him to understand that this question is addressed specifically to the situation in which we, readers of “Experience,” find ourselves. So, too, is the answer that follows: we find ourselves “in a series of which we do not know the extremes, and believe that it has none. We wake, and find ourselves on a stair; there are stairs below us, which we seem to have ascended; there are stairs above us, many a one, which go upward and out of sight.”4

An Emerson essay is a series, a series of sentences, a series of “stairs,” that is, steps—steps that move us in the direction of “realizing” the world we “think.” We do not “know” the “extremes” of this series, insofar as this essay as a whole, the second in Essays: Second Series, is itself a step in such a series. The essay’s end returns us to its beginning, indicating that after we take the last step, our next step is to take the first step. To “realize” the world we “think” requires that we acknowledge that our world stands in need of “realizing.” It requires acknowledging the passing of a world, and a self, that had seemed real to us. Haunted by the death of its author’s young son, “Experience” is at one level about—at one level is—a process of mourning. Yet images of pregnancy and birth are ubiquitous within the essay. They are among the essay’s “self-images.” There is a particular birth that the writing seems to be expecting: the birth of the essay itself—as if by envisioning its writing as pregnant with itself, “Experience” gives birth to itself, as we must give birth to ourselves if we are to walk in the direction of the unattained but attainable self.

Giving birth to itself, to the thinking its writing expresses, Emerson’s essay aspires to “realize”—to make real, to give birth to—the new world, the new America, its writing “thinks.” As we have seen, Vertigo begins and ends by envisioning its own birth or creation. As we have also seen, North by Northwest envisions itself, precisely as “Experience” does, as giving birth to itself. And it ends, as Emerson’s essay does, by returning us to its beginning. To be sure, North by Northwest’s prevailing mood, comic and at times ironic, is a far cry from the profound sense of loss that haunts Emerson’s essay. Psycho is more open in meditating thoughtfully, even somberly, on the unsettling, vertigo-inducing way that the world on film gives birth to itself.

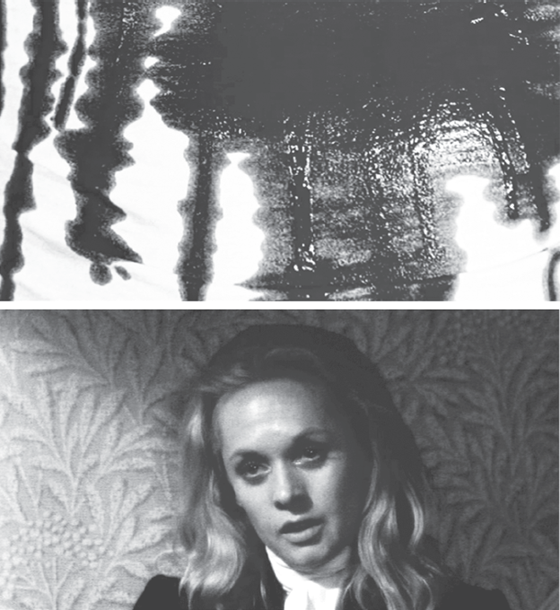

Figure 15.1

Marnie’s opening credit sequence, ostensibly modest and even old-fashioned, together with the shot that follows it, takes a further step in Hitchcock’s ongoing meditation on the creation or birth of the projected world. The credits are presented as if they were pages of an old-fashioned photo album or, perhaps, a guest book. The first “page” contains the words “UNIVERSAL PRESENTS,” together with the studio logo.

Universal’s globe, less endearing but no less familiar than MGM’s roaring lion, has evolved over the years, but it has always looked three-dimensional, with the continents outlined as realistically as possible, and it has always been spinning. The globe conveys both that the studio’s movies are seen around the world and that the stories they tell likewise span the globe; wherever Universal movies are shown, the world is projected on the screen. In Marnie, “UNIVERSAL PICTURES RESENTS” is not set apart from the opening title sequence; it appears as if printed on the first page of a book, a page no different, in principle, from the pages that follow. And the globe is reduced to a circle with the continents crudely sketched inside it. It is not an image of a world spinning in infinite space; it is an image only of an image of the world—a picture on a flat page that is itself a picture projected onto a flat screen.

The transition to the last title, “Directed by ALFRED HITCHCOCK,” like all the “page turnings,” is effected by a slow wipe. But from this title to the first “real” shot of the film, there is a direct cut, rather than another wipe or a conventional fade-out/fade-in. We are taken abruptly, without any conventional transition, from the pages of a book that is not real, in either our world or the film’s world, to our first view of what is, within the projected world, reality. The abruptness is reinforced by the fact that just before the cut, Bernard Herrmann’s swelling music—I believe that Herrmann’s score for Marnie is his greatest achievement—concludes with a forceful chord but without resolving harmonically. The abrupt shift to “natural” sound feels like the sudden emergence of silence—all we hear are footfalls that echo unnaturally in the silence from which they emerge. The combined effect of these devices is to make a subliminal yet strong connection between the name “Alfred Hitchcock,” credited on the last “page” as the film’s director, and the solitary object that materializes within the frame: a bright yellow handbag, shot end-on. (Readers of The Murderous Gaze might recognize the resemblance of this object, thus framed, to the black bag, emblematic of the lodger’s mysterious project, which The Lodger associates with Hitchcock’s own mysterious “project,” the first of a series of acts of artistic creation that link Marnie with all the Hitchcock thrillers that precede it.)

Figure 15.2

Viewed end-on, this object, which stands out within an otherwise almost completely black frame, forms a circle that precisely matches the circle to which the Universal globe is reduced on the first “page.” It is as if the globe becomes this handbag, as if the handbag is, or contains, the world as a whole, the way a mother’s womb is, or contains, the unborn child. The folds within this circle endow the object with a suggestive aspect that reinforces, visually, the conventional Freudian association, which Hitchcock films have often jokingly exploited, between women’s handbags and what to Freud were the twin mysteries of female sexuality and motherhood.

The sound of footfalls and the bobbing movements of the yellow handbag enable us to know, before we actually see, that in reality this object is held by a woman who is walking away from a camera that is keeping pace with her movement. I would add “as she walks into the depths of the frame,” except that up to this point within the shot, the woman, the handbag, and the surrounding blackness eclipse all else, keeping the frame from having, or appearing to have, any depth at all. It is as if the camera and this object that holds its complete attention, as circular as the camera lens itself, have not yet become separate. We know that what we are seeing is an object in the world, but it appears before us as if it were in no real space, like Scottie’s falling body at the climax of the dream sequence (if that is what it is) in Vertigo, which is suspended between reality and unreality—as, indeed, the projected world always is. After a moment, however, the camera slows. No longer keeping pace with the woman, it enables the world on film, and this woman within it, to be revealed, to reveal itself. Then the camera stops altogether as the woman, a brunette dressed in gray and carrying a large gray suitcase as well as her yellow handbag, her footfalls still echoing, recedes into the depths of this frame—depths that her movement, combined with the camera’s cessation of movement, causes to open up, visually, transforming the depthless frame into a signature Hitchcock tunnel shot and opening a bracket that will be closed near the end of the film. What this frame contains is reality, but it is a reality that bears an unreal, dreamlike aspect, an unreal reality “signed” with a Hitchcock signature.

Film images are of the world. Reality is re-created, re-creates itself, in its own image, when it is captured by the camera and projected onto the movie screen. The world on film is reality itself, albeit reality transformed by being thus captured and projected. It is a defining feature of the medium of film that the reality of the camera’s presence is also the reality of its absence. Indeed, as we have seen, it is one of Hitchcock’s guiding intuitions that the medium of film overcomes or transcends our commonsense distinctions between the real and the unreal, between presence and absence, between reality itself and inner reality.

Figure 15.3

“If I have described life as a flux of moods,” Emerson writes in “Experience,” “I must now add, that there is that in us which changes not, and which ranks [i.e., outranks] all sensations and states of mind.” The passage goes on in language that is as precise as it is poetic: “The baffled intellect must still kneel before this cause, which refuses to be named.…—Suffice it for the joy of the universe, that we have not arrived at a wall, but at interminable oceans. Our life seems not present, so much as prospective; not for the affairs on which it is wasted, but as a hint of this vast-flowing vigor” (485–86). The world our eyes see, which our particular mood paints in its hue, is a world in which “souls never touch their objects.” Objects “slip through our fingers…when we clutch hardest at them,” as Emerson vividly puts it. “I take this evanescence and lubricity of all objects, which lets them slip through our fingers then when we clutch hardest, to be the most unhandsome part of our condition.”5

Cavell understands Emerson to mean that what is “unhandsome” in our human condition is not that “objects for us, to which we seek attachment, are, as it were, in themselves evanescent and lubricious.” Rather, the “unhandsome” part of our condition is “what happens when we seek to deny the standoffishness of objects by clutching at them, which is to say, when we conceive thinking, say the application of concepts in judgments, as grasping something, say synthesizing.”6 What is “unhandsome” about us is not that we are finite, limited in our powers, that our concepts and judgments lack unity, that we are creatures of moods. What is “unhandsome” is our “clutching at things” in our human effort to escape our humanness.

Hitchcock was powerfully drawn to the idea that we live our lives in private traps within which, in the words of Norman Bates, “For all we scratch and claw, we never budge an inch.” Norman Bates is no Emersonian. Nor was Emerson a Batesian. Yet Emerson could write, in “Intellect,” that “every man beholds his human condition with a degree of melancholy. As a ship aground is battered by the waves, so man, imprisoned in mortal life, lies open to the mercy of coming events” (418). Our “unhandsome” efforts to escape our humanness are doomed to fail. But if being “imprisoned in mortal life” is the human condition, as in melancholy moods we take it to be, how different is Emerson’s vision from Norman’s? If we are imprisoned in our mortal lives, is not our humanness a trap in which we were born—a trap we can never escape for all we “scratch and claw,” as Norman puts it, or for all we “clutch at things,” to use Emerson’s virtually identical metaphor?

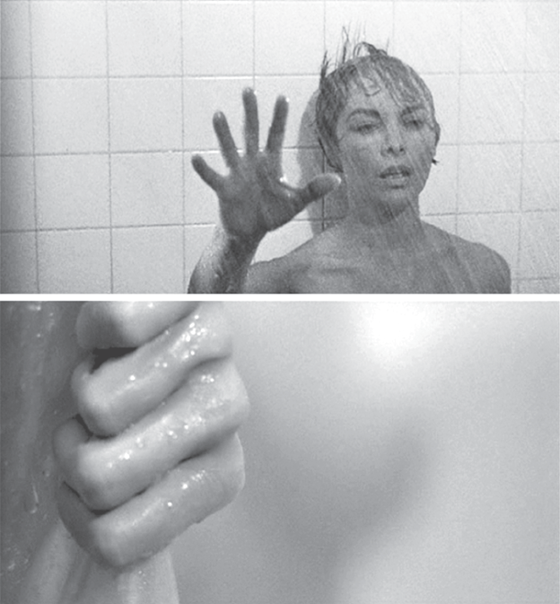

“Clutching” is one of Emerson’s “master tones.” In Cavell’s view the idea that what is “unhandsome” is our “clutching at things” in our human effort to escape our humanness is central to the philosophical enterprise Emerson took himself to be founding, which in the New World was to replace the European edifice of philosophy. It is a striking coincidence—is it simply a coincidence?—that images of hands clutching, clutching at, holding things in their clutches, and so on, are among the signature motifs that appear at crucial moments in every Hitchcock thriller. Think of Alicia, in Notorious, clutching the key to the wine cellar. Or Bruno, in Strangers on a Train, desperately reaching through the grating for the lighter that seems just beyond his reach. Or the dying Bruno involuntarily unclenching his hand, revealing to the police the telltale lighter he had been holding in his clutches. Or Manny, in The Wrong Man, alone in his prison cell, staring at his own hands, clutching at nothing. Or Scottie, in the opening of Vertigo, losing his grip on the policeman’s hand and watching in horror as the man falls to his death. Or Roger, in North by Northwest, desperately clutching Eve’s hand as she dangles precariously from the sheer face of Mount Rushmore. Or Babs in Frenzy, clutching her murderer’s incriminating tie pin so tightly, even in death, that he has to break her fingers, one by one, to pry it from her grip. Or Marion, in Psycho’s shower murder sequence, her body slowly sliding down the wall, looking with glazed eyes in the direction of the camera as her hand reaches out to something she cannot see, something whose presence she senses—as if she were trying to reach the camera, or reach the screen, or, rather, to reach through the screen to our world on the “other side.”

At this moment in Psycho the camera pulls slowly away, precisely reversing the movement by which it had earlier allowed the shower curtain to engulf the movie screen—as if the “safety curtain” that separates us from the projected world, and the shower curtain Marion’s murderer tears asunder, were one and the same. Then Marion’s hand, framed in extreme close-up, continues its movement until it grasps the shower curtain in the foreground. She is clutching it for dear life. But her grip is so strong, so fierce, that it bears an aspect of violence, as if she were struggling less to hold herself up than to pull the curtain down with her as she falls, her life’s blood draining away.

As this haunting shot makes explicit, Hitchcock’s recurring images of hands clutching, clutching at, holding things in their clutches, and so on, have a self-referential dimension, as do all his signature motifs. Like Emerson’s “master tones,” they are self-images in Cavell’s sense. That is, they participate in the films’ thinking—at one level, their thinking about their own way of thinking, about film’s way of thinking. Cavell characterizes Emerson’s philosophical enterprise—which he takes his own writing to be inheriting—as the “overcoming of thinking as clutching.”7 Hitchcock’s art of pure cinema can be characterized the same way. His films invite—or provoke—us to open our eyes to the fact that films do not think by “clutching at things.”

Had Hitchcock consciously sought a way to express, cinematically, Emerson’s guiding intuition that what is most “unhandsome” about us is our effort to escape our real condition by “clutching at things,” he could not have come up with a more perfect illustration than the moment—a crucial turning point—when Marnie, having unlocked the office safe, reaches out toward the stacks of twenty-dollar bills inside, but finds her hand unable, or unwilling, to grasp the money, however desperately she clutches at it.

Figure 15.4

All her adult life Marnie, a thief, has “clutched at things,” not wisely but too well. But it is at the moment Marnie recognizes the futility of her efforts to reach the money in the Rutland office safe that she first knows in her heart, if not yet consciously, that her real wish is to change, to abandon the way of thinking that has for so long imprisoned her, a way of thinking that Hitchcock envisions, metaphorically, as “clutching at things.”

Figure 15.5

Marnie’s mood at this moment is very different from Marion’s. In taking a step, not yet fully consciously, toward the unattained but attainable self, Marnie is, to paraphrase Bob Dylan, busy being born, not busy dying. By visually equating Marnie’s clutching at the money with the gesture of reaching toward the camera, the close, frontal framing of her clutching hand conveys the impression that what makes the money unreachable by her is what makes the camera unreachable by her, what makes the screen unreachable by her, what makes our world unreachable by her, what makes her world unreachable by us.

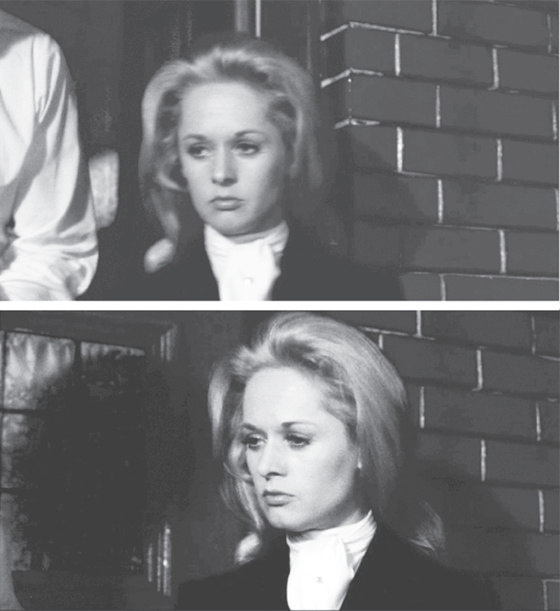

Few viewers at the time appreciated the sympathetic consideration The Birds accords the relationship of Melanie and Mitch, Annie’s moving death, or the haunting, haunted figure of Mitch’s mother. Fewer still were prepared for Marnie’s emotional intensity and the unbearable sadness unmitigated by its “happy ending.” In Marnie, as in The Birds, there are no murderous villains, although mean-spirited Strutt (Martin Gable) and jealous Lil (Diane Baker), who are unkind to Marnie, come close. And Bernice, Marnie’s mother, whose inability to express her love causes her daughter inestimable suffering, is a tragic figure.

Bernice’s most poignant moment comes at the end, when her daughter finally acknowledges that her mother has always loved her, and Bernice responds by saying, “You were the only thing in this world I ever did love.” Still, she holds back from fully expressing her love, first, by referring to Marnie not as a person but a thing (a “thing” she acquired when she let a boy have sex with her in exchange for his sweater, the beginning of her career as a prostitute); second, by not even now caressing Marnie, although her hand is poised just above the golden hair her daughter had always longed for her to caress; third, by forcing Marnie to pull back from physical contact by saying, as she had several times in the film, “Get up, Marnie, you’re aching my leg.”

Figure 15.6

After tenderly brushing Marnie’s hair back with his hands (a gesture that Robin Wood convincingly takes to be the emotional climax of the film),8 Mark (Sean Connery) leads Marnie out of her mother’s house, promising to return her someday soon. Marnie looks back at Bernice, sitting alone with her thoughts and memories in the gathering darkness, and says, “Good-bye.” “Good-bye,” her mother answers. Not holding back from expressing his compassion for this woman who is incapable of expressing the love she feels, Hitchcock’s camera stays with Bernice as Mark and Marnie exit. Only then, when Marnie is gone, does she add, in a loving voice her daughter will never hear, “…Sugarpop.”

I find it natural again to refer to the camera here as “Hitchcock’s” because Marnie breaks with The Birds’ rhetorical strategy of identifying the camera with the awesome, mysterious “something” The Birds represent, a “something” that is specifically not human. Nor does it revert to The Wrong Man’s strategy of ceding control of the camera to God. Marnie is not a return, however, to Hitchcock’s earlier practice of using the camera to declare that he is the God who holds sway over the world of the film. It is Hitchcock’s own humanity—what he has in common with these characters—no less than theirs, that shines through here. But this means that Hitchcock does not try to keep the camera in his own clutches. He acknowledges, at least rhetorically, that there are limits to his power and that the camera has its own nature, its own instincts and powers, that no merely human author can claim for his or her own.

When Mark first takes Marnie to Wykwyn, his family’s estate, to meet his father, jealous Lil, who had feigned a sprained wrist so as to make Marnie serve the tea, hoping she didn’t know how to do it properly, and not wanting the two lovebirds to be alone, tries to contrive to accompany them to the stables, where Mr. Rutland keeps his horses. Mark says to Lil, “I’m sure your sturdy young wrist has recovered sufficiently to pour Dad another cup of tea.” Holding up her wrist, she protests “I can’t!” Rubbing it in, Mark replies, quoting Emerson, “When Duty whispers low, Thou must, / Then youth replies, I can.”9 “Ratfink!” Lil shouts, lowering the level of discourse a notch, as Mr. Rutland (Alan Napier) reaches for another slice of his favorite Horn & Hardart butter cake. “And you misquoted!”

Emerson’s line is actually “The youth replies, I can,” not “Then youth replies, I can.” But even though Mark misquotes Emerson, he seems to have read him and to have taken his philosophy to heart. This is clear from a little scene sandwiched between the passage, during their honeymoon cruise from hell, in which Mark promises Marnie that he will be kind to her and will not touch her again, and the controversial passage often referred to as the “rape scene.”

Mark, trained as a zoologist, is sitting with Marnie at a table in the ship’s lounge, he with a tall cocktail, she a glass of orange juice. He is telling her about a phenomenon of nature he thinks will be of special interest to her: “In Africa, in Kenya, there’s quite a beautiful flower. It’s coral colored with little green-tipped blossoms, rather like a hyacinth. If you reach out to touch it, you’d discover that the flower was not a flower at all, but a design made up of hundreds of tiny insects called fattid bugs. [This should be spelled “flatid,” but out of deference to Jay Presson Allen, the film’s screenwriter, I will continue to spell the word the way she does in her shooting script.] They escape the eyes of hungry birds by living and dying in the shape of a flower.”

In his highly informative book The Making of “Marnie,” Tony Lee Moral sees this speech as “the crux of the film.” He quotes Allen, who articulated its point this way: “In any aspect of beauty, there may be extremely ugly elements, but the overall thing is beautiful. Marnie has terrible problems, but [Mark] sees her as a beautiful thing.”10 (I have no doubt that, if the screenwriter had been pressed and had been in the mood to be more expansive, there is much more she could have said about it.)

In the shooting script, Mark prefaces his little speech with “There is no such thing as ‘the norm’; we’re all singular,” and ends it by adding that the bugs seem to have invented the flower they imitate, “as there is none other like it in nature.…Even the flower the bugs imitate is singular.” And when Marnie does not look up, “he kills the rest of his drink” and all but barks, “As singular as I am, Marnie—as singular even as you.” The film omits these lines—perhaps because they make their point so obviously and directly, as opposed to the evocativeness of the central part of the speech they bookend. Omitted in the film, too, is Marnie’s overt lack of interest, which risks conveying the impression that Mark’s speech simply goes over her head. Tippi Hedren’s Marnie is as smart as Sean Connery’s Mark. Nothing either says goes over the other’s head.

“Lady animals figure very largely as predators,” Mark had pointedly remarked to Marnie earlier in the film, when he had arranged for her to be alone with him in his office and asked her to type an article he wrote titled “Arboreal Predators of the Brazilian Rain Forest.” Significantly, he is now no longer characterizing her as a predator but as a vulnerable animal instinctively hiding behind a mask designed to be a defense against predators. The beautiful mask that it is the fattid bugs’ collective instinct to create enables them to survive in a bird-eat-bug world that revolves around killing. Mark is saying to Marnie, without saying it in so many words, that he has come to understand that she is not really the predator he had thought she was; that he, too, is not a predator; and that she can trust him, can safely reveal herself to him as she is, “for herself,” as Vertigo’s Judy would put it, because he knows he will find her true self just as singular, just as beautiful, as her mask.

But the beauty of the fattid bugs’ mask serves only to deceive hungry birds into mistaking it for a real flower, which they have no interest in eating, whereas the beauty of Marnie’s mask is seductive. Were its only purpose to hide her vulnerability from predatory men who would otherwise desire to devour her, figuratively speaking, why has she created for herself a mask those predators find irresistibly attractive? Mark does not yet know—nor do we, nor does Marnie herself, at least consciously—what happened to her when she was a child, or, rather, what she did, that motivated her to create this mask. Did Marnie create this beautiful, seductive mask because, unconsciously, she wishes for revenge against men, like Elsa in “Revenge” and Rose at the end of The Wrong Man? Or did she do so to keep from awakening to the truth about herself that she had killed a man? Is she torn between a longing to open her eyes and the fear that if she were to awaken, she would discover that she is a killer by nature?

Predators burn bright with beauty, too, of course. The beauty of nature masks the ugliness of killing. But the ugliness nature’s beauty masks is also a mask. What it masks is the singularity of everything in nature—even predators, and even creatures whose instinct is to protect themselves from predators by appearing other than what they are. The Emersonian point of Mark’s fable is that everything in nature is beautiful, because everything in nature strives instinctively to exist, to become its unique self—including Marnie.

And including Marnie.

Mark, who understands human behavior to be rooted in instincts inherited from animal ancestors, wants Marnie to take to heart the fattid bug “flower” as a metaphor for herself. But Hitchcock wants us also to understand it as a metaphor for the film we are viewing. A clue that Marnie posits the fattid bug “flower” as one of its own “self-images” is the fact that when Mark says that fattid bugs “escape the eyes of hungry birds by living and dying in the shape of a flower,” virtually every word—escape, eyes, hungry, birds, living, dying, flower—resonates with ideas and images that recur in every Hitchcock film. Flowers, eyes, and birds, in particular, are quintessential Hitchcock motifs or signatures. And they resonate with each other; for example, Vertigo links flowers and eyes, as we have seen; in The Birds, the horrifying image of Lydia’s neighbor’s bloody eye socket links eyes and birds.

Taken as a metaphor for Marnie, the fattid bug “flower” suggests that if we look closely at the film—as we are doing—we will find its hundreds of “petals” to be shots representing individual moments, each a vulnerable creature, metaphorically speaking, a being that strives to exist, to become what it is capable of being. Each is possessed of the universal instinct to protect itself. And each is possessed of the more specialized instinct to protect itself by joining with others of its kind to mask its nature by collectively taking on the look of a beautiful flower. When we first encounter Marnie, we see it from a “bird’s eye” perspective, as it were. Those viewers who see the film with the eyes of “hungry birds” are deceived; having no appetite for flowers, they see no reason to look any closer. Only those who find this flower-that-is-no-real-flower irresistibly attractive are moved to look more closely. What Marnie is designed to mask, it is also designed to move us to unmask. To what end?

If Marnie were a whodunit, the climactic revelation that Marnie’s mother had been a prostitute, and that as a child Marnie had killed one of her johns, would be the solution to the mystery that was the film’s raison d’être. To be sure, Marnie’s flashback is a profound and moving sequence, brilliantly conceived and executed, but it is not privileged over other sequences. If Marnie is a train of “moods of faces and motions and settings,” every moment captures and casts a singular mood. Every moment of Marnie is singular. Every moment is beautiful. Film achieves its particular poetry, as Cavell suggests, when it achieves the perception that “every motion and station, in particular every human posture and gesture, however glancing, has its poetry, or you may say its lucidity.” Emerson writes in “The Poet” that “it is not metres, but a metre-making argument, that makes a poem—a thought so passionate and alive, that, like the spirit of a plant or an animal, it has an architecture of its own, and adorns nature with a new thing” (450). In Marnie Hitchcock’s art of pure cinema becomes an art of pure poetry.

No less than an Emerson essay, Marnie is designed to call forth, in those moved to respond to its call, an experience in which we “find the journey’s end in every step of the road.”11 It would be only a slight exaggeration to say that the events that unfold in the “flashback” are the film’s MacGuffin. Its revelation of what happened to Marnie in the past is central to making the screenplay’s Marnie the character she is. But it is not in the same way central to making the film’s Marnie, at every moment the camera relates to her, the beautiful creation of the art of pure cinema that she is. In Hitchcock’s film, as opposed to Jay Presson Allen’s screenplay, Marnie’s past only participates in creating or revealing Marnie’s singularity when the camera makes it present, when it is present to the camera. The “flashback” does not explain what “caused” Marnie to act in the singular ways we witness throughout the film. For it offers no explanation as to what causes her child self to act in the singular ways she does in this sequence.

As a child, the “flashback” reveals, Marnie’s instinct was already to find herself repelled by the sailor’s closeness, to call out in her distress to her mother, to respond to her mother’s own call for help by killing the man Marnie believed, wrongly, was killing her mother, to take pleasure in her own act of violence, and to scream in horror and revulsion at the sight of the blood of the man she had killed. The self-knowledge Marnie achieves by reliving this unbearably painful childhood experience is not a matter of learning what caused her to become the way she is. It is a matter of awakening to the reality that this is her past, is her past, and that she has now put it past her.

To a degree unprecedented in a Hitchcock film, Marnie pays privileged attention to the thoughts and moods of its characters, not to the author’s fate or the conditions of Hitchcock’s authorship. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say that what is unprecedented in Marnie is its commitment to breaking down or transcending that opposition. At every moment, the camera does something to call our attention to the characters’ thoughts and feelings and moods. In Marnie the camera’s relationship to the characters is at every moment so intimate—even, or perhaps especially, when their motivations are inscrutable to us—that all of its revelations of their thoughts and feelings and moods are also revelations about the camera itself.

The camera declares itself at every moment in Marnie, declares itself in everything it does, not only when it performs spectacular gestures. This has always been true of Hitchcock thrillers, as the original five readings of The Murderous Gaze demonstrate. But in the long new chapter on Marnie I wrote for the book’s second edition, I demonstrate that in this film it is this fact or condition that is precisely what the camera is declaring whenever it declares itself. One way to put this is to say that to an unprecedented degree Hitchcock identifies with the characters in Marnie; their reality is a reflection of his own “inner reality.” Paradoxically, another way to put the point is to say that in Marnie, again to an unprecedented degree, Hitchcock acknowledges his characters’ separateness from him. This is what frees him to love them, and to express his love for them, to a degree that is new for Hitchcock. Does it free him from the fate of killing the things he loves?

Marnie is not a story of unrelieved suffering like The Wrong Man. Nor is it a tragedy like Vertigo. Indeed, it rivals North by Northwest in the pleasures with which the film generously rewards us. Chief among these pleasures are found in the many conversations between Marnie and Mark, or, rather, their one conversation, with many interruptions, that runs the length of the film. In this ongoing conversation Marnie fully holds her own with Mark—and, miraculously, the inexperienced Tippi Hedren fully holds her own with the charming and charismatic Sean Connery. Indeed, Marnie gets more than her share of the wittiest lines. For example, when Mark, his voice dripping sarcasm, asks her where she learned to speak and behave as if she were born into wealth and privilege, as he was, Marnie replies, with perfect comic timing, but also genuine anger at society’s unjustness, “From my betters.” Marnie’s wittiest line in the film occurs when at the beginning of the free association “game” she cuts him short by saying, “You Freud, me Jane?”

Regrettably, Hitchcock went along with Truffaut, in their book-length interview, by speaking mockingly of dialogue sequences, disparaging “talking heads” as uncinematic. In truth, though, as Marnie demonstrates as convincingly as Psycho, no director has ever known better than Hitchcock how to turn great conversation into great cinema. When heads talk like Mark and Marnie (that is, like Sean Connery and Tippi Hedren, speaking lines written by Jay Presson Allen, as directed by Alfred Hitchcock, photographed by Robert Burks, edited by George Tomasini, and accompanied by music composed by Bernard Herrmann), and when the camera attends to their conversation with the kind and degree of attention necessary to follow their thoughts and capture their moods, the result is a triumph of “pure cinema.” Without this triumph the film would not fully earn its ending, which is worthy of the great remarriage comedies Cavell writes about. For we have no doubt, from the quality of the conversation each can have with no one else, that however grave her problems, or the conflicts between them, Mark has met his match in Marnie, and Marnie has met her match in Mark.

Marnie has become a touchstone. I find Robin Wood’s judgment to be only slightly hyperbolic when he says, in the documentary on the making of the film that is included with the DVD release, “If you don’t like Marnie, you don’t really like Hitchcock. I would go further than that and say if you don’t love Marnie, you don’t really love cinema.” Marnie is, for reasons Wood understood, one of Hitchcock’s greatest achievements (as Wood’s two essays on Marnie, written almost forty years apart, are among his greatest achievements as a film critic).12 But I would slightly revise his formulation to say that if you don’t really love cinema, you cannot love Marnie; you cannot know what makes the film so singular, so beautiful. But even if you do love cinema, Marnie can be difficult to like, much less love. Even more than The Birds, Marnie is infused with a deep sense of loss, an urgency, an emotional directness, but ultimately an affirmation, that sets it apart from other Hitchcock films. To fully appreciate the film’s beauty, we have to open ourselves to the pain, as well as the pleasure, it calls upon us to feel. We have to trust the film, as I have learned to do—as Marnie has taught me to do.

These days, unfortunately, even lovers of cinema find themselves aggressively prodded to distrust the film. Marnie’s reputation has been tarnished by the oft-repeated assertion that the film contains an offensive rape sequence that definitively exposes Hitchcock as an arch misogynist and by Donald Spoto’s claim, which many take to be proof positive that Hitchcock was an egregious sexist, that near the end of production there was an incident in Tippi Hedren’s trailer in which the director said or did something inappropriate to his star.13 We will never really know what—if anything—actually happened in that trailer between director and star. And it is none of our business.14 According to Spoto, this incident, and the anger and bitterness it caused, led Hitchcock to lose interest in the film, and this—along with the supposed fact that his once advanced techniques had become antiquated—led to the unreal-looking process shots and painted backdrop that many take to be grievous flaws. Production and postproduction records make clear, however, that Hitchcock never stopped being actively engaged in the film.15 In any case close attention to the film itself makes clear that Marnie set new standards even for Hitchcock in its precise and masterful use of a wide range of cinematic techniques, including devices new to him, such as the handheld camera he used in the climactic “flashback” sequence. Furthermore, the much-maligned process shots and backdrops can plausibly be seen as strengths, not weaknesses, of the film.

In the fox hunt, for example, there are traveling matte shots in which there is a noticeable disjunction between foreground and background, as if they were separate worlds.

Did Hitchcock intend this as a means of conveying, expressively, that Marnie is more dreaming this ride than living it—the sense that her inner reality, the ecstasy of freedom expressed by her face, is more real to her than what philosophers call the “external world”? I don’t know a good reason to doubt this, especially because Hitchcock’s use of this strategy culminates, in this section of the film, with the shot of Marnie’s gun firing, in sharp focus in the foreground, and Forio, her beloved horse, out of focus in the background, suddenly convulsing and then lying still.

I do not believe, however, that Hitchcock intended for us to be conscious that the visual disjunction between foreground and background is caused by a special effect. If the juxtaposition of “inner” and “outer” realities simply appears fake, a mere contrivance, that would be a flaw in the film. These shots don’t strike me that way. Evidently, for some viewers they do. But why judge this to be a flaw so grievous that it justifies denigrating or dismissing Marnie as a whole, rather than a rare failed experiment in a film that features so many daring experiments that succeed beyond expectation—unless one were looking for an excuse, a cover story, to rationalize not being open to the disturbing emotions Marnie calls upon us to feel?

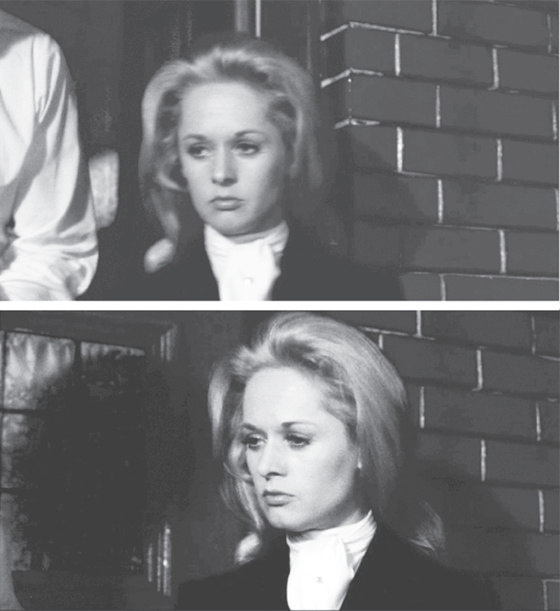

Figure 15.7

Figure 15.8

The so-called rape sequence, one of the most disturbing in Marnie, is preceded by a passage, painful in its own right, that takes place the first night of the cruise. When Mark finally goads Marnie into emerging from the bathroom, he strokes her face, ready to kiss it, when she suddenly pulls away, shouting, “I can’t! I can’t! I can’t!” Mark responds to her earnest “If you touch me again, I’ll die!”—a line altered from the screenplay’s “If you touch me again, I’ll kill you!”—by promising not to touch her. “I’ll feel the same way tomorrow, and the day after tomorrow, and the day after that,” she says, her gesture of turning her face away from Mark underscoring the ambiguity as to whether this is a prediction or a vow.

Figure 15.9

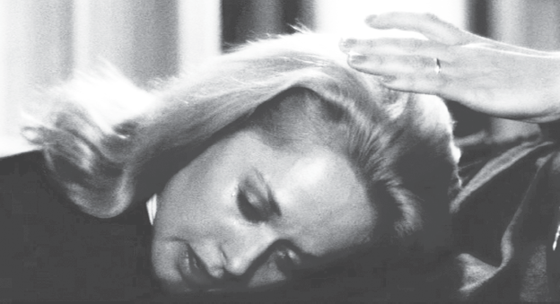

“Let’s try at least to be kind to each other,” says Mark. “Kind!” she retorts, almost choking on the word. “If that’s too much, I’ll be kind to you, and you’ll be polite to me.” “You won’t!” “I won’t,” he echoes her, as she had echoed him. Without irony, he adds, “I give you my word.” Marking his words, she looks at him in silence. “Well, let’s try and get some rest. How about it? You, in your little bed over there. Me, light years away, in mine here.” Recognizing that this sarcasm is not a disavowal of his promise, she says, “Thank you.” Mark quietly goes to his room, and there is a cut to an eloquent long shot of Marnie, melancholy in her solitude, then a slow fade to black.

The alleged rape scene takes place after three brief sequences—the third contains the “fattid bug” speech—that serve to indicate that Mark and Marnie have been on the ship for so many days—and nights—that their tempers are frayed.

Evan Hunter, who had written the screenplay for The Birds and whom Hitchcock had hired to adapt Winston Graham’s novel, felt that this scene, as Hitchcock wanted him to write it, was offensive. When he wrote an alternative scene for Hitchcock’s consideration, he found himself peremptorily fired and replaced (thank God!) by Jay Presson Allen. The scene she wrote in accordance with Hitchcock’s wishes proves Hunter wrong. But the fact that so many critics believe that Mark’s behavior is unforgivable reveals the magnitude of the risk that Hitchcock felt compelled to take for the sake of his art.

The sequence begins with Mark peering over the top of a book (Animals of the Seashore) he is ostensibly reading (just as Marnie had ostensibly been typing when she was really watching Susan at the safe), looking through the open door to the bedroom. Marnie, in a nightgown, appears at the doorway. She says “I’ll close the door, if you don’t mind. The light bothers me.”

Robin Wood, with his customary insightfulness, points out that if Marnie simply wanted the door closed, she would have closed it herself without saying anything to Mark.16 By saying “if you don’t mind,” while knowing full well that he does mind, she is provoking him to respond the way she must know, at least unconsciously, that he will. “Hm, what’s that, dear?” Mark replies with mock politeness, picking up but not drinking from what seems to be a tall glass of whiskey and water on the table beside him. “The light? Oh, yes, of course. You’ve been an absolute darling about my sitting up reading so late. I’m boning up”—the pun intended?—“on marine life since entomology doesn’t seem to be your subject, and I’m eager to find a subject, Marnie, any subject.”

No doubt Mark is frustrated sexually. But he is also frustrated by Marnie’s continuing rejection of his efforts to engage her in conversation. We might assume that it is only a particular conversation, a conversation about a particular subject—the subject of her rejection of him sexually—that he really desires. But what he says is that he is eager for a conversation on any subject. Does he say this only because he believes that any conversation would be a step in the direction of their having the particular conversation he desires, a conversation that might lead to overcoming the obstacle of whatever it was that had “happened” to her to cause her to resist him? Or is conversation, like sex, something he desires in and of itself?

In any case, when Marnie responds to Mark’s sarcastic words, her conscious intent is to thwart, not satisfy, his desire for conversation. Again, she provokes him. “All right. Here’s a subject. How long? How long do we have to stay on this boat, this trip? How long before we can go back?” Mark responds to this provocation with an anger and bitterness beyond anything we have witnessed before. “Why, Mrs. Rutland, can you be suggesting that these halcyon honeymoon days and nights, just the two of us alone together…should ever end?” To this, Marnie responds by turning her back, withdrawing into the bedroom, and slamming the door behind her. For a moment Mark stares at the closed door. Then he leaps to his feet and barges in.

That Marnie is deliberately frustrating Mark’s desire for conversation doesn’t mean she has no desire for it. In the years between his first take on Marnie and his second, Wood—goaded, he tells us in Hitchcock’s Films Revisited, by V. F. Perkins’s provocative question “Does Mark cure Marnie?”—had come to believe, as I believe, that throughout the film Marnie wishes, albeit unconsciously, to be “cured” and gradually becomes conscious of harboring such a wish.17 Like Dexter in The Philadelphia Story, Mark plays an essential role in the transformation of the woman he loves, but the impetus has to come—and does come—from Marnie. At crucial moments, Mark believes he is leading Marnie, when she is really—if unconsciously—leading him. In the pivotal “free association” scene, for example, it is Marnie, not Mark, who takes the initiative. It is she who provokes him to play the “game” in the first place, then provokes him to push her to the point of breaking down and crying out to God for somebody to help her. She is too smart not to have known, unconsciously, that the “game” would inevitably end this way. The question of consciousness aside, there are thus exact parallels between Marnie’s (unconscious) plan and Judy’s (conscious) plan, as I have come to understand it. The chapter on Marnie in the second edition of The Murderous Gaze shows in detail how the film tracks the stages by which Marnie’s unconscious wish to be cured emerges into consciousness, preparing her for the momentous step of letting her old self die so that a new self can be born. As I also show, Marnie tracks the stages by which Mark comes to recognize, and accept, that he is not—cannot be—in control of this process, that his powers are limited.

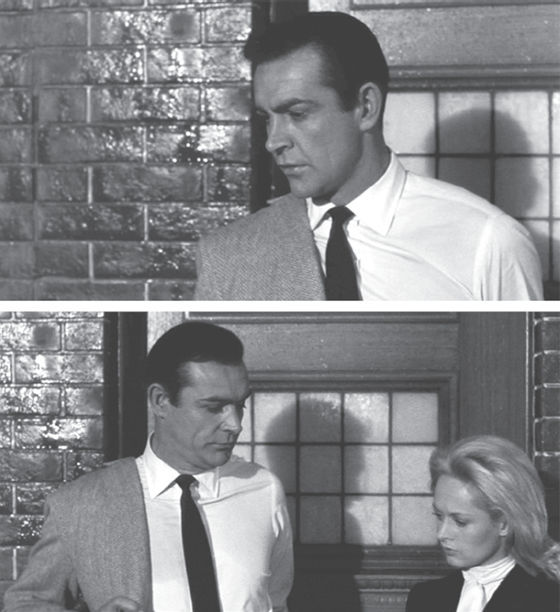

Once inside the bedroom, Mark stands at a distance from Marnie, his half of the frame in shadow.

“If you don’t mind, I’d like to go to bed,” Marnie says, her choice of words (perhaps unconsciously) provocative. “I’ve told you the light from the sitting room bothers me.” “We certainly can’t have anything bothering you, can we?” Saying this, Mark angrily slams the door, casting the entire frame in shadow. With a calm forcefulness that belies her inner turmoil, Marnie says, “If you don’t want to go to bed, please get out.” The camera begins moving in, excluding her from the frame, until it isolates Mark in a medium close-up as he says, menacingly, “But I do want to go to bed, Marnie. I very much want to go to bed.” Framed in eminently Hitchcockian fashion with a lamp beside her, Marnie cries out “No!” (in what the flashback will reveal, in retrospect, to be her “little girl” voice). She is still staring at Mark, unhinged by what she sees in his eyes, when we cut to her point of view of his grimly determined face. Mark’s face jerks slightly toward the camera, and we cut back to Marnie. His hands intrude into her frame and pull her nightgown down. There is a cut from her shocked face to her gown falling to the floor past her now bare legs. We cut back to Marnie’s face, wide-eyed and expressionless, then back to Mark.

Figure 15.10

Because the camera is on Marnie, not on Mark, when her naked body is exposed to his gaze, what this last shot discloses is not his immediate reaction. By the time the camera returns to him, he is looking into her eyes, not at her body. He is mortified by the shattered look his action has caused. For Mark this is a moment of awakening comparable to Roger’s when he learns that Eve is a double agent. He says, “I’m sorry, Marnie,” acknowledging that he has broken his promise to be kind, as she had predicted he would. Never again will he be unkind to her. Never again will she say no to him—until he demands, out of kindness, that she confront her mother.

We cut to a shot that frames Mark and Marnie in profile. Within this frame, Tippi Hedren’s profile is haloed, as we might put it, by the circular porthole through which we see the blackness of the night. Between Mark and Marnie, in this frame, is a curtain that forms a Hitchcockian ////. Mark takes off his robe and gently covers Marnie’s bare shoulders. Cradling her head in his hands, he brings her face closer to his, as the camera moves in. His lips meet hers in a kiss. Marnie does not resist. And yet a cut reveals—a revelation hidden from Mark—that her eyes are wide open and staring fixedly in the direction of the camera.

Figure 15.11

Surely, if at any point Marnie were again to say, “No,” Mark would not go on. That she offers no resistance gives him grounds for believing that after his sincere apology she now trusts him, and gives us grounds for believing, as he does, that he is making love to her, not raping her. As Hitchcock films this moment, Marnie even seems to move on her own accord to the bed, although backward, as if in a trance. Mark pulls away from her enough for a shot from his point of view of Marnie’s face, never more beautiful, to fill the frame—except for the background, which is out of focus, but legible enough for us to understand that he is gently laying her down on the bed. We cut to an extreme close-up of Mark, his face half in shadow so dark we see only one of his staring eyes.

Figure 15.12

This shot of Mark’s hypnotic stare is taken from Marnie’s perspective, but because in the previous shot she had appeared entranced, turned inward, it feels as if what we are now viewing is what she is imagining, not what she is literally seeing. When we cut back to Marnie, her face, too, is half in shadow. As Allen’s shooting script puts it, “Her face is a blank, staring blindly at the ceiling above her. It is completely exposed to us, and on it is written…nothing. There is no flicker of expression, of emotion.”

Figure 15.13

This language makes clear that Allen believed, as I do, that Mark thinks he is making love to Marnie, not raping her. At the same time, Allen believed that Marnie thinks she is being raped, as her shooting script implies in its assertion that “fear and revulsion” are “manifest in her frozen face.” Surely, however, if “nothing” is “written” on Marnie’s frozen face, her face does not “manifest” anything. It is possible to view her face as frozen with fear—that is, to project fear onto its blankness. But revulsion implies an impulse to recoil. We can project revulsion onto a blank, frozen face only if we interpret its immobility as a symptom of an inner conflict, a standoff between repulsion and attraction.

Figure 15.14

One might think a screenwriter’s view is definitive on a matter like this, but that is not the case. Allen intended Marnie’s state of mind to be unambiguous. But her intention—and even Hitchcock’s—only matters insofar as the film itself realizes it. All that really counts in this case is what the camera reveals in Marnie’s—that is, Tippi Hedren’s—face at this moment. And her face, like Mark’s, is half in light, half in shadow. At every moment of her relationship with the camera, the film’s Marnie, divided against herself, is deeper and more ambiguous than the woman the screenplay characterizes so insightfully. The screenwriter’s conviction that Tippi Hedren was miscast—too old, too icy, not vulnerable enough—is proof positive that the film’s Marnie and the screenplay’s Marnie are positively not the same dame.18

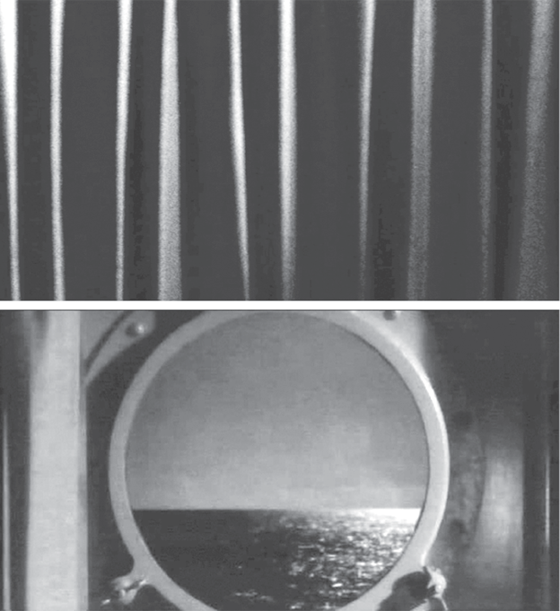

The sequence ends, mysteriously, with the camera panning from Marnie’s face, past a curtain that fills the frame with the //// that in Hitchcock films is associated with the movie screen, to a porthole as circular as the camera lens. This circular porthole forms a frame-within-the-frame within which we see the sky and the calm sea—a vision as still and timeless as the sleep of death. The camera holds on this symbolically charged framing as the image fades out.

Why am I defending Mark? Because I take him at his word when he says, just before proposing to Marnie, “It seems to be my misfortune to have fallen in love with a thief and a liar.” He is declaring his love. To be sure, he is declaring his love in Sean Connery’s insouciant, almost sarcastic, manner. But Marnie acknowledges that he means what he says when she responds, “Oh Mark, if you love me you’ll let me go.” When she adds, “I’m not like other people. I know what I am,” he replies, “I doubt that you do, Marnie. In any event, we’ll just have to deal with whatever it is that you are.” Then he adds, “Whatever you are, I love you. It’s horrible, I know, but I do love you.” “You don’t love me,” she retorts with rising anger, not so much doubting his sincerity as frustrated by his lack of self-knowledge: “I’m just something you’ve caught.”

Figure 15.15

Mark may seem to be pleading guilty to Marnie’s charge when he replies, at once amused by the absurd situation and moved by the depth of Marnie’s feeling and his own, “That’s right. You are. And I’ve caught something really wild this time, haven’t I? I’ve trapped you and caught you, and by God I’m going to keep you!” But with these words Mark is reaffirming, not disavowing, his love, I believe. He is “taking on the responsibility” for her, as he puts it, because he loves her. The film asks us to believe that Mark already knows he loves Marnie when he proposes marriage in the least conventionally romantic proposal scene in the history of cinema (if not of the human race). But Mark’s understanding of what his love for Marnie entails—what “love” means, what the responsibility is that he is taking on, and what its limits are—deepens as Marnie unfolds. It will ultimately bring Mark to the point at which, by knocking on the wall of her mother’s living room, he opens the floodgates that release the memory Marnie had been repressing at a terrible psychic cost. Once Marnie’s memory begins to flood in, Mark understands, and accepts, that all he should do, all he can do, is to act as a midwife, to direct by “indirection,” by asking questions whenever needed to prod her to describe what she is seeing and hearing. Over that scene, which takes place at once in the past and the present, at once inside and outside Marnie’s mind, Mark has no control.

“By the time you go into that trauma in Baltimore,” Hitchcock said to his crew, “I don’t want any normality to intrude anywhere.”19 At critical moments throughout the film, Marnie’s experience uncannily foreshadows the climactic flashback. Thus it is perfectly natural that the flashback’s “nonnormality” should be foreshadowed, visually, as it is in the film’s remarkable opening and, as I show in the new Murderous Gaze chapter, at many other points in the film. And this brings us to the much-maligned backdrop. Both the first and last times we see it, the view is expansive, and the camera is shooting from an elevated position.

Did Hitchcock intend this backdrop to appear real? I believe so. Did he intend it also to appear unreal? I believe that as well. That does not mean he intended for us to be conscious that the backdrop is a backdrop. Surely, he didn’t want it simply to look fake. When the footage came back from the laboratory, Robert Boyle, Hitchcock’s production designer for North by Northwest and The Birds as well as for Marnie, was concerned that the painted backdrop didn’t look real. When he assured Hitchcock that it could be fixed by being textured, Hitchcock responded that he thought that wasn’t necessary. Boyle’s understanding of this response, as expressed many years later, is that if the backdrop looked like a backdrop, that was a trivial problem of little importance to Hitchcock, who was concerned with “deeper matters.”20 Boyle’s interpretation seems eminently reasonable. And yet, to Hitchcock, the relationship of reality and unreality is one of those “deeper matters.”

Figure 15.16

Figure 15.17

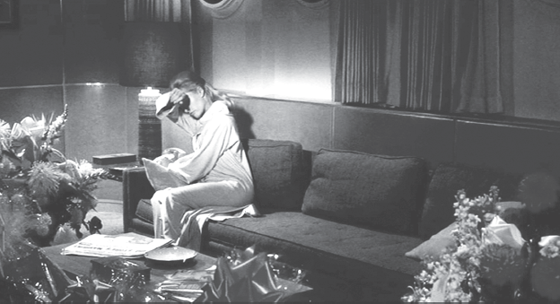

When Mark drags a reluctant Marnie to her mother’s house in Baltimore, we cut directly from the two in the car riding on the open highway to the front of the house. Rain is falling. Then we cut to the street, with the freighter looming large at the end of it. Here, the view is anything but expansive.

Lit intermittently by flashes of lightning, the street now looks even more unreal. More precisely, there is a disjunction, visually, between the real-looking street in the foreground and the looming freighter, harbor, and threatening sky in the background, which do not look as if they exist within real space. To me the background looks less like the painted backdrop it really is than like reality reduced to an image projected on a flat screen—which it also really is. The fact that this is another Hitchcock tunnel shot, that it is designed to draw our eyes into the depth of the frame, underscores our impression that in this frame depth is an illusion.

Its play with depth and flatness, with presence and absence, with reality and unreality, links this shot to the film’s opening shot of Marnie on the platform. The two shots are bookends between which the body of the film is contained. In the opening shot we see only Marnie. In the present shot we see no one; the disjunction between foreground and background is not a projection of Marnie’s “inner reality.” No one within the projected world is dreaming this moment. This is our dream, or Hitchcock’s dream, or the camera’s dream. In the opening shot Marnie’s act of walking away from the stationary camera enables the worldhood of the world to be revealed, to reveal itself. In the present shot, there is no one to perform such an act. The camera itself, moving of its own accord, transforms a semblance of unreality into a semblance of reality by tilting down to reveal Mark’s car in front of the steps leading up to Bernice’s front door. He is trying to drag a reluctant Marnie, not yet visible, out of the front seat.

When Mark demands that Bernice tell Marnie the truth—which he believes he knows—about her “bad accident,” she rebukes him by saying that she is the only person who knows what really happened. When he insists that Bernice has to help her daughter remember the past so that she can stop being haunted by it, Bernice becomes hysterical. Screeching, “You get out of my house!” she rushes at Mark with flailing fists. “You get out!” He has no choice but to forcefully hold her off. Over her mother’s screams we cut to Marnie, who, as the script puts it, “watches this grotesque struggle with widening eyes that suddenly become fixed, dilated.” In the child’s voice we have heard before, Marnie cries out, “You let my mama go! You hear? You let my mama go! You’re hurting my mama!”

At the sound of her voice, Bernice and Mark cease their struggle and stare at Marnie. Mark asks her directly, “Who am I, Marnie? Why should I want to hurt your mama?” “You’ re one of them. One of them in the white suits.” Framed in close-up, Bernice steps forward and shouts, “Shut up, Marnie!” Mark, in close-up, cuts her off. “No! Remember, Marnie…” We cut again to Bernice, her face an anguished mask, as Mark continues excitedly, “…how it all was…” We cut back to Mark. “…The white suits! Remember?”

Figure 15.18

Mark looks at Marnie with an expectant smile. When we cut to her, she seems about to speak. Then she loses the thread. The camera returns to Mark. His face falls. But disappointment gives way to determination. When we cut back to Marnie, she is staring vacantly. And Mark’s hand, closed in a fist, is present with her in the frame. The hand taps three times on the wall.

The camera is on Mark as he asks, “What does the tapping mean, Marnie?…” We cut back to Marnie. “…Why does it make you cry?” The camera moves in to a very tight close-up as she says, “It means they want in.” Still not looking at Mark, her gaze turned inward, she continues: “Them in their white suits. Mama comes and gets me out of bed. I don’t like to get out of bed.”

Who is speaking these words? Although we have on occasion heard this child’s voice emanating from Marnie, it is not her “normal” voice. Ordinarily, she speaks in an adult woman’s voice—a cultivated voice wiped clean of all traces of her mother’s “poor white trash” southern accent, a voice Marnie must have cultivated with precisely that intention. Who is the “she” who re-created herself, at least outwardly, as the woman who speaks in this cultivated voice? This “she” is the little girl Marnie has never stopped being—the child who seems to recognize no difference between Mark and “them in their white suits” yet who answers the questions he poses to her, and thus really does see him as other than one of “them.” Insofar as Marnie is this little girl, her “normal” voice is not really normal; it is the voice of a character the child has created, a role she has made her own, a role she plays virtually all her waking hours, a role she isn’t conscious of being a role. Until Marnie acknowledges that she is—that she has become—the woman she has only been pretending to be, until this woman becomes real, her “normal” voice isn’t Marnie’s real voice. It is closer to the truth to say that her real voice, her voice when she isn’t acting, is that little girl’s voice.

In Vertigo, as we have seen, when “Judy” in her voice-over expresses the wish for Scottie to love her “as she is, for herself,” she cannot be wishing for him to love the “Judy” who is only one of her roles, a role that so perfectly denies her “inner Madeleine” that she had to have created it for that purpose. Her wish must be for him to love the actress she really is. The woman we know as “Judy” is always playing a character, always playing a role she has made her own. We never see her “as she is, for herself,” because there is nothing she is “for herself.” But when Marnie speaks in her little girl voice, she is not acting. The child who doesn’t like to get out of bed, who wishes to go back to sleep, perchance to dream, is who Marnie is “for herself.” We can thus say that if she is to walk in the direction of her unattained but attainable self, it is not the adult Marnie who must change; that woman does not yet really exist. She who must change is the child Marnie still is. This little girl must awaken—awaken to the reality that she has become the woman she outwardly appears to be. Only then can this woman—Marnie’s new self—really exist within the world.

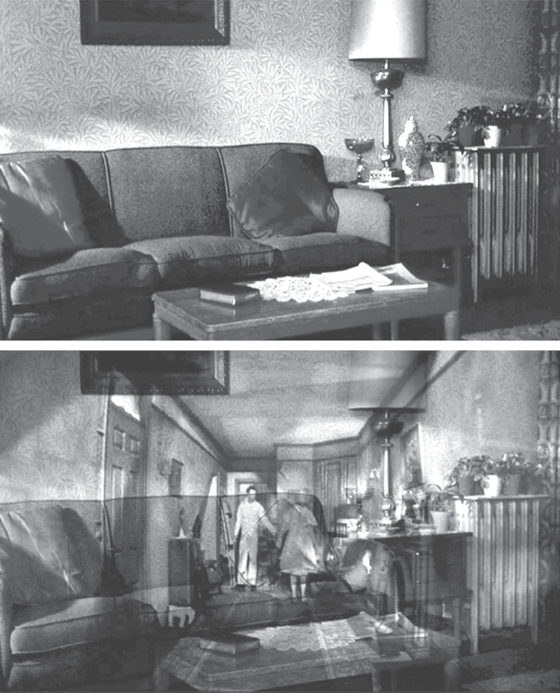

For a long moment, Marnie falls silent as her eyes become fixed. When we cut to Marnie’s point of view, we see nothing special—only a corner of the living room. Against the wall is a green sofa, one of its throw pillows centered in the frame. There is a lamp and a radiator to the right of the sofa. As the camera continues to stare fixedly, this nondescript view begins to change. This new view is, first of all, yet another tunnel shot. The walls on both sides, the ceiling, and the rug on the floor of an almost bare living room all converge in an exaggerated way toward the vanishing point to create what the shooting script calls a “long perspective”—a space that seems at once exaggeratedly deep, like all tunnel shots, but also exaggeratedly flat. In the center of the frame, where the pillow had been, is a region, the shape of an old-fashioned cameo picture frame, in which everything is slightly—but noticeably—lighter in color than what is outside it. The entire image is faded and almost monochrome, like an old sepia-tinted photograph, an association that enhances our sense that we are looking into the past.

Figure 15.19

Near the far end of the room, framed in the “cameo,” are a young, attractive Bernice, her back to the camera, and (this comes as no surprise) a man dressed in white, evidently a sailor (Bruce Dern, a veteran of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, in his first movie role), who is standing in front of an open door, blocking our view of the room behind him. As the sailor moves to the edge of the “cameo,” we see, in the room beyond the door, the foot of a bed. Young Bernice goes into that room and, saying, “Come on, Marnie, get up,” drags the child out of bed.

All this time, the shot’s perspective has been continuously shifting. Using a variant of the technique developed for Vertigo of simultaneously zooming in, thus changing the focal length, and moving the camera out, the background looms larger, the “cameo” expanding almost to the edges of the frame. The space appears to flatten, to lose its depth—making the foreground appear as distant as the background, not making the background seem closer. We do not have the sense of a disjunction between foreground and background, as in the shots of the Baltimore street, with its painted backdrop, or the traveling matte shots of Marnie riding. The effect here is the opposite: foreground and background virtually fuse. We do sense a disjunction, but it is between ourselves and the projected world, the world we are viewing through the eye of a camera that remains fixed in place. Or in no place.

Our impression, indeed, is that the camera cannot move within the world it is framing, because no matter how close what we are viewing may appear, the camera is looking in from outside that world. It is as if there can be no place for the camera within this flattened, depthless frame, because the frame contains no real space, is no real space. What we are viewing morphs from a shot that presents Marnie’s literal point of view, as she is staring in the present in the direction of her mother’s sofa, with the camera in her real position, into a shot that presents—what? Is this a scene she is only conjuring in her imagination? Or is it somewhere, somehow, really taking place? To Marnie, surely, it is really happening. It is happening now. But how can this be, if this is the past, not the present? And how can this be reality to Marnie if she is viewing it from the outside, where the camera is? Then again, is reality ever fully real to Marnie, who lives her life as if she were only dreaming it?

Can we say that the projected world here is not a reality the camera is capturing but a reality the camera (in league with the projector) is creating—making it real by projecting it, that is, by projecting Marnie’s inner reality, rendering the invisible visible? Marnie stared at the sofa in her mother’s living room for what seemed an eternity before what is “really” present began morphing into the past. Has she conjured this past into being? (Strutt called her a “little witch.” Is she one?) Does she will the past to appear in the present, or does she find herself subjected to a will not her own? We cannot say. It is clear, though, that once the metamorphosis happens—once it becomes the past that is present within the frame—the genie cannot be put back in the bottle. Marnie has no more power than we do—than we ever do when we are viewing a film, or when we are remembering the past—to alter the events that are unfolding. It is also clear that once Mark sets the machinery in motion by tapping three times on the wall, he has no role to play within these events. And it is clear, as I have said, that he accepts this condition, which in any case he is powerless to change. Mark’s powers are limited. So are ours. So are Hitchcock’s.

Bernice pulls little Marnie into the living room, lays her on a sofa, tucks her in, and, saying, “You go on back to sleep, Sugarpop,” kisses her. While we are viewing this, the sailor is beginning to undress. “Bernice,” he calls to her impatiently. She leaves her child’s side, leads him into the bedroom, and closes the door behind them. All this the camera has framed from its fixed position.

A split second before the door completely shuts, we cut to Marnie in the “present.” I put the word in quotes here, because this sequence calls into question whether in the medium of film there is a clear distinction between past and present. As the sequence develops, both the “past” and the “present” become equally present to Marnie, present in the same way (and also absent in the same way). Evidently, Marnie has been deeply absorbed in the scene we have been watching. Just when we expect to hear the closing door hit the jamb, we hear, instead, a deafening clap of thunder. Marnie’s eyes widen in terror, and she recoils violently, flattening herself against the wall. Is her terror caused by the thunder in the “present” or by the thunder in the “past,” its deafening sound coinciding with the “missing” sound of the closing door, which to the little girl signifies her mother’s abandoning her for the man in the white suit? We cannot say.

Astonishingly, we now cut to little Marnie, her golden hair facing the camera. With a scream, little Marnie, who had been sitting up in bed, buries her face in the pillow. As the camera reframes to follow her abrupt movement, then on its own pans jerkily to the left until it excludes her altogether and frames nothing but a section of the closed bedroom door, it becomes clear that it has broken away from its fixed position. The camera has breached the barrier separating it from the world of the “past” and now finds itself inside that world, like the projectionist Buster Keaton plays in Sherlock Jr., who jumps “through” the screen into the world of the movie he is projecting. The terrifying thunderclap straddles the two shots, the two spaces, the two times, the two worlds. The camera is now not only located within the little girl’s world but is also handheld and fitted with a telephoto lens that narrows its field of vision.

That the camera is now inside the “past” world, free to move within it and attuned, responsive, to the experience of the terrified child, suggests that Marnie in the “present” is no longer merely imagining this scene or viewing it from the outside, as we are. She is living it. This is no memory. This is no dream. Marnie in the “present” is the little girl living this scene. Is the presentness of the past an illusion? On film the “past” is no less real—and no less unreal—than the “present.”

For Marnie, the “past” had literally been a dreamworld—a “private island,” if one she longed to escape from, not escape to. Now, this “private island” has become reality to her. As long as the camera was filming this “private island” from Marnie’s literal point of view outside it, her perspective coincided with ours. Now that her experience coincides with that of the little girl within that world, our perspectives no longer coincide. We are viewing Marnie. Marnie is not viewing herself. She is living within the world we are viewing. This means that the camera no longer affords us direct access to Marnie’s experience. It also means that Marnie no longer has access to the views the camera presents to us. Who or what, then, is the source of these views? Can they be trusted?

When this flashback culminates in little Marnie’s killing the sailor by hitting him repeatedly with a poker, Marnie, in the “present,” tilts her head and says, exactly as she had after she shot her beloved Forio to put an end to the injured animal’s suffering (and exactly as Hitchcock did when he returned to the screen at the end of “Breakdown” after we had suffered the sponsor’s message), “There, now” in a voice the shooting script describes as “dreamy, soft, satisfied.” When Marnie says this to her dead horse, to his departing soul, her voice is “dreamy, soft, satisfied” because she has succeeded in ending Forio’s suffering and sending him off to greener pastures. After Marnie kills the sailor, by contrast, she is satisfied because she wanted to kill this man—this man she didn’t like, this man she didn’t want to kiss her, who smelled funny, who she believed was hurting her mother. The only way I can make sense of this moment in the film is to hear Marnie as speaking to her own departing soul—as if when she killed the sailor, her own self also died, and she is reassuring herself that death is for the best. When Marnie relives this act of killing, experiences it as if for the first time, and acknowledges it as her own, her innocence dies, the way in Lifeboat the Americans’ innocence dies when they kill Willi. Marnie says, “There, now,” in the voice of the child she no longer is. She says it in a “dreamy, soft, satisfied” voice. But that dreamy mood survives only a moment longer. Then she sees the blood.

Figure 15.20

We cut to young Bernice, emitting the scream she had been stifling; to the child Marnie, who screams as well; to the bloody face of the dead sailor; then to his shirt, with dark red lines, forming a ////, running up and down the larger red stain, glistening with fresh blood. The camera tilts up until the frame is filled with the red of the blood. Finally, there is a slow dissolve to Marnie in the “present,” her scream mingling with the others until they all subside into silence.

When the frame, awash with blood, dissolves into Marnie’s face staring with horror in the direction of the camera, is she seeing what Judy sees at the end of Vertigo when the shadowy figure, emerging from the blackness, so frightens her that she steps back and falls, or jumps, to her death? Is she seeing what Lydia’s friend sees before his eyes are pecked out? Is she seeing what we see, at the end of Psycho, when the death’s head appears superimposed over Norman Bates’s grinning face?

Mark says to Marnie, “It’s all over. You’re all right.” But he has not seen what she has seen. When she emerges from her trancelike state, she is changed. Having looked death in the face—the sailor’s and her own—Marnie awakens to the true dimension of killing. And it is a woman, not a child, who awakens. A new self is born.

Mark sums up the moral, as he understands it, by saying, “It’s time to have a little compassion for yourself.” Not a bad moral, as morals go. He adds, “When a child, a child of any age, Marnie, can’t get love, it takes what it can get any way it can get it.”

After Marnie’s final, deeply moving conversation with her mother, we cut to the front of the house. Mark and Marnie are on the stoop outside the door they have just exited. Mark turns on the narrow top step to shut the door. To give him room, Marnie moves a little to her left. These are small movements, but their combined effect is to remove Mark from the frame and replace him with his shadow.

Marnie has moved only a few inches, enough for her position in the frame to change by just a small fraction of its width, but her motion is so quick she seems to scoot across the frame. She stops on a dime the instant we hear the closing door hit the door jamb—the very sound that coincided, in the “flashback,” with the deafening thunderclap that precipitated the camera’s transition from outside to inside the world of Marnie’s past. The way Marnie abruptly halts her movement here that gives this shot a jolting impact. This kinesthetic effect reinforces our impression of the abruptness with which Marnie’s attention is drawn to a sight—or vision—that has intruded into her awareness.

The next shot seems to represent Marnie’s point of view. Because at the moment of the cut she is framed more in profile than full face, however, it is ambiguous whether what follows represents a reality she is literally seeing or an “inner reality”—no less real, no less unreal—that she is envisioning, or conjuring, in her imagination.

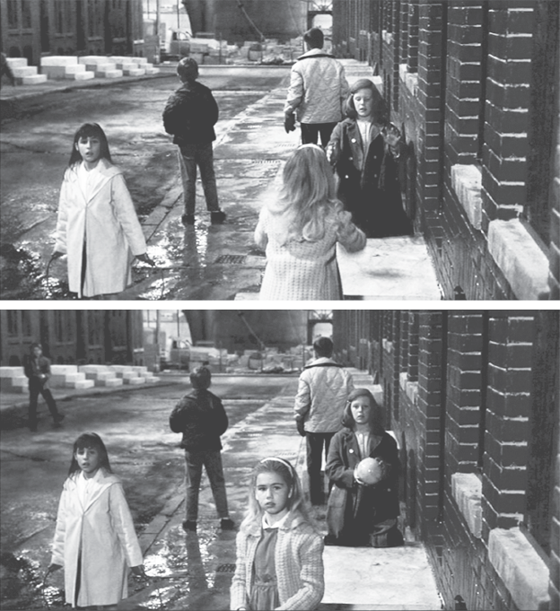

We see four children in the street. Two boys, facing away from the camera, standing motionless, like sentinels, and two girls, facing the camera and looking in its direction. The girl on the left is wearing a white coat. Both girls have their arms and hands outstretched, as if in a posture of supplication or surrender, an association underscored by the fact that the girl on the right is on her knees. The girl on the left, who has been jumping rope, takes one last quick jump and then stands stock still, staring directly at the camera. At the same time, a third girl, with golden hair and a yellow sweater the color of Marnie’s handbag from the film’s opening shot, enters the center of the frame from below, enhancing the air of unreality. The effect is uncanny, as if she were crossing the barrier separating the projected world from our world. The blond girl bounces a ball to the girl on the right, who catches it in her outstretched hands and then also just stands there, staring at the camera. The blonde, as if sensing that she is being watched, turns and confronts the camera with her gaze. She, too, stands motionless, continuing to stare at the camera—at Marnie. And at us.

Figure 15.21

Figure 15.22

Her gaze, like that of the other girls, is certainly not friendly. Nor is it threatening, exactly—as long as its injunction is obeyed to keep out. It is as if Marnie sees these girls as ghosts from her past, not real children in the present—as if they are in their own world, vigilant to keep Marnie—and us—out. On film their world is a “private island” as real, and as unreal, as “reality” itself. Even if she wanted in, Marnie could not enter that world any longer. Nor is their world our world.

Surprisingly, we do not cut to Marnie to witness her reaction but to Mark. At the head of this shot, the camera frames him more in profile than full face, precisely as it had framed Marnie a moment earlier. He has just seen the children we have seen. That they are real does not mean that they are not also projections of Marnie’s imagination. Mark now knows Marnie well enough to see them the way she sees them. He slowly turns counterclockwise, the camera panning and moving out in smooth synchronization with his motion until it includes Marnie with Mark in the frame (and with his shadow between them).

Marnie says to Mark, “I don’t want to go to jail. I’d rather stay with you.” These words may remind us of the epitaph W. C. Fields proposed for his own gravestone: “I would rather be living in Philadelphia.” But I hear Marnie’s line as ironic, as comic understatement, even though she says it soberly, in full seriousness. She is not really saying to Mark that staying with him in Philadelphia is the lesser of two evils. What she is saying, without literally saying it, is that she wishes to stay with him. Her choice of the word stay is significant in that it acknowledges that she already is with him. “I’d rather stay with you” is Marnie’s declaration of love, her vow of marriage or remarriage. “Had you, love?”—said with a warm smile as he puts his arm around her—is Mark’s.

Figure 15.23