FRIDAY, APRIL 4, 2014—5:29 A.M.

The streetlights are still bright at this hour when Daniel Bryan gets into a chilled limousine for the earliest scheduled appearance of his week. With little time to eat a formal breakfast, he reminds the car of the fruitfulness of his initial Whole Foods mission.

“This is where a grocery store trip comes in handy,” Bryan states. “I had a protein shake, a banana, and vegetable juice.”

He shares the ride with Sheamus and the Shield’s Roman Reigns and Seth Rollins, all attendees at the morning’s international media event at the New Orleans Ernest N. Morial Convention Center—the same site where WrestleMania Axxess, WWE’s annual fan festival, is being held. They arrive along with the rest of a larger group that includes Big E, Cesaro, Natalya, and Emma; then the Superstar squad is divided for interview conquering.

Bryan’s very-early-morning interviews include discussions with local news affiliates, satellite radio stations, and more at emptied booths on the Axxess floor, many hours before the doors open for the second night of fan festivities. Interviewers rap with Bryan about everything from his upcoming nuptials and WrestleMania to his indie star days and WWE training grounds.

Daniel Bryan’s on-camera interview is brought to a halt by a second buzz in his pocket, like a record scratch on the meet-and-greet music being made by the media on hand. It’s the “Yes!” Man’s mom. The dual calls are a signal for Bryan’s attention, so he politely pauses the Q&A to connect with his mother, whom he’s expecting to arrive in New Orleans later in the evening.

He ends the call, “Yeah, I love you, too.” Then it’s back to countless conversations for broadcast and beyond. It’s ordinarily difficult to see the expressions beneath Bryan’s beard, but as he exchanges banter with the myriad media personalities, there are plenty of wide smiles visible.

Shortly after I returned from my first trip to England, I did the December tour for New Japan, then drove back down to Santa Monica to resume living in the Inoki Dojo, which had changed while I was gone. Justin McCully must have had some sort of falling-out with them, as he was no longer there. There were now several other guys living in the dojo, having made the same decision I did to move there to train. One of them bought a cot and put it above the office close to mine, which I didn’t mind, but it greatly diminished the amount of privacy I had. Simon and Hiroko Inoki brought in more teachers to help us, including two different yoga teachers, a new jiu-jitsu coach, and a Muay Thai coach. With all the guys there and the different classes, it was a great learning environment. I’ve loved yoga, grappling, and kickboxing ever since.

In 2004, New Japan brought me over for eight different tours, the longest of which was over six weeks. Being there so much allowed me to get more comfortable with the style and get to know the Japanese wrestlers better. In March, I won my first Japanese title, the IWGP Junior Tag Team Championship, along with a masked Christopher Daniels. Chris wrestled as Curry Man, a bizarre dancing character whose mask included a curry bowl on top of his head. The Japanese fans loved him, and I always found it funny that Chris wasn’t actually a very big fan of curry.

In May, I wrestled on another Tokyo Dome show, in which I teamed with Último Dragón and Koji Kanemoto to wrestle Tiger Mask, Heat, and Marufuji—my best experience in the Dome. I ended up getting the pin for my team, demonstrating the faith New Japan had in me. That May was also the first and only time I competed in the annual Best of the Super Juniors tournament, a three-week, sixteen-man round robin tournament that dated back to 1988. It was supercool because so many of my favorite wrestlers had done the tournament, including Owen Hart, Chris Benoit, Eddie Guerrero, Fit Finlay, and, of course, Dean Malenko. It’s a physically intense tournament, and early on, Chris dislocated his shoulder. We were scheduled to defend our tag team titles in the middle of the tour, so Chris taped his shoulder up every night and continued on. We lost the championships to Gedo and Jado, but the match was great because all the fans knew Chris was hurt and got behind him big-time. Afterward, Chris was able to go home.

As far as the tournament went, I made it to the semifinals—much better than I thought I’d do—where I lost to Kanemoto. I felt like Kanemoto and I had had a really good match, but when I watched it, I realized Kanemoto performed light-years better than I did, and I recognized I still had a lot more work to do. That was one of the many wonderful things about working in Japan. On the United States independent scene, I was almost always the more experienced wrestler and had led the matches since 2002, even only three years into my career. Very few of us had experience working with veterans in the industry. It was almost like the blind leading the blind. In Japan, it was different. The first time I wrestled Kanemoto, he’d been wrestling twelve years. Jushin Liger had already been wrestling for eighteen years against some of the best in the world by the time I wrestled him. It was a wonderful place to learn.

Though I only got to wrestle him a couple of times in tag matches, Yuji Nagata was my favorite person to watch perform. He didn’t really do any fancy moves, but everything he did was believable and crisp; plus, he had a great fire, and the fans always got behind his matches. I made sure to watch his matches every night because there was always something I could learn from them.

Midway through 2004, I had an unexpected surprise that improved my quality of life. Simon and Hiroko Inoki had always been very nice to me, and one day, they asked if I wanted to move into the Inoki Sports Management apartment. It was an offer I couldn’t refuse. The apartment, which cost nearly $3,000 a month, was a two-bedroom on Sixth Street in Santa Monica, only a handful of blocks from the beach. It was the most expensive place I had ever lived, and I got to live there for free. Being around wrestling 24/7 at the dojo was good for me for a while, but there were times when I needed a break, and the apartment provided that. I had my own room, so I slept better. I had a full kitchen, so I ate better. I had a place to get away to, so I had time to relax. The apartment was only a couple of miles away from the dojo, too, so on nice days I could ride my bike there. And of course, if I had a free day, I could enjoy the beach or walk on the Third Street Promenade.

At times I had a roommate. One, briefly, was former UFC Light Heavyweight Champion Lyoto Machida, because he was under contract with Inoki Sports Management. There have been rumors that he drank his own pee, but I never saw it. I also lived with Shinsuke Nakamura, who was a young New Japan wrestler training for his first MMA fight. Nakamura and I got along really well, and he ended up being a huge star for New Japan.

At this point you may be dying for some sort of crazy party story—like, maybe I took advantage of this prime location to lure strippers into my place and snort cocaine off their fake breasts—but nothing like that happened. The only perverse thing that I experienced there took place as I walked back to the apartment. A man in a black SUV pulled up beside me and asked if I worked out. I said I did. He asked where, and I told him I worked out at the 24 Hour Fitness down the street. He next asked if I liked it and I said it was all right. Then he asked if he could pay me to let him suck my cock. I said, “No thanks,” and that was it. He drove off to find another man to service, and I kept walking back to the apartment.

In between tours, I continued to wrestle on independent shows, mostly for Ring of Honor. Earlier in the year, I won a ROH tournament called Survival of the Fittest, which came down to me and Austin Aries, who’d just started with ROH a couple of months earlier. Gabe Sapolsky, the booker, loved the finals and subsequently booked Aries and me in a two-out-of-three-falls match that August at Testing the Limit. I was talking to Gabe on the way to the airport when he told me he’d advertised that each fall had a one-hour time limit. I thought that was weird, especially since there was no plan for any of the falls to go an hour; it was just going to be like any other two-out-of-three-falls match. But then I started thinking. I envisioned leveraging the significant time limit. We could go to an hour draw in each of the first two falls, then—just when it looked like we were going to a third hour-long draw—somewhere around fifty-five minutes in, Aries would beat me. I called Gabe back and told him my idea. At first he thought I was joking and laughed, but the more I talked to him, the more he realized I was serious. Given the business model of ROH, the most important thing was selling DVDs and tapes. If we did what I had planned, it would be the longest pro wrestling match in modern history, and my justification was that a ton of ROH fans as well as non-ROH fans would buy it, even if they fast-forwarded through most it. Gabe started to come around, and he eventually said I could do it if I wanted to.

When I landed in Philadelphia, I ran the plan past Aries. Gabe had spoken with him earlier, and at first Aries thought he was ribbing him. After he realized it wasn’t a joke, it didn’t take long for Aries to agree to the concept. My only concern was the live fans and keeping them engaged. Nothing kills a match quite like a crowd that’s bored, but I came up with what I thought was a brilliant idea. Since we were on last, we would have the ring announcer tell the fans that it could end up being a long match and that neither performer would be offended if an audience member decided to head home. That’s right, my brilliant idea was to encourage people to leave in the middle of my match. I thought it would be easier to wrestle the three hours if we didn’t have to worry about entertaining people live, and I knew the commentary would make it easier for people to watch at home. Unfortunately, people weren’t leaving, but they were getting bored, so we improvised and went to our backup plan, exchanging a few falls in what became a seventy-six-minute bout. It is still the longest match of my career, though I’ve always been disappointed we didn’t go the full three hours.

Around this same time, the Inoki Dojo started running some shows. Simon and Hiroko worked with a few other people who knew the promotions side of wrestling very well, and they also sought some of us who trained there for our advice on booking the shows. We sat in several long meetings coming up with how we should book the first show.

Rocky Romero, Bobby Quance, and TJ Perkins had done a long tour of CMLL (Consejo Mundial de Lucha Libre) in Mexico, and Rocky had become friends with Negro Casas, one of the bigger Mexican stars. Since CMLL television programming aired in the Los Angeles area, which has a sizable Hispanic population, we thought bringing in one or two guys like that would be our best bet. From there, we could fill out the rest of the card with those of us who trained at the dojo, along with a couple of fly-ins. Everyone seemed to agree that this would be the best bet and went to work. They booked a Mexican restaurant/nightclub for the show, and it seemed like it would be perfect.

I left for Japan, and when I came back, I found out the idea had changed. Instead of bringing in Mexican wrestlers for the show, they flew in two Japanese wrestlers named Nishimura and Takemura. Nishimura was quite popular in Japan but not very well known in the States, and Takemura was barely known in Japan. The show bombed, drawing about forty-five people and losing around $30,000, I heard. The intentions were good, but it was yet another example of one of the important things in wrestling: You have to know your audience.

Later that year, I continued to try to help Simon and Hiroko by recommending they consider Jamie Noble, a rugged yet immensely talented cruiserweight. I’d wrestled Jamie in early 2003 on WWE’s syndicated show called Velocity—one of several times I worked for WWE as an enhancement talent. Most enhancement talent were given very little offense since we were there to make the contracted WWE stars look as good as possible. Jamie just wanted to have a good match, though, so we went back and forth, with me getting in considerably more offense than a situation like that warranted. Our short TV match went really well, so in late 2004, when Jamie was released from WWE, I immediately went to Simon and Hiroko. I told them he would be perfect for New Japan and his talent could really strengthen the gaijin juniors division.

The connection was made with New Japan, and Jamie was booked for the December tour. He and I teamed on a regular basis, and though I’d met him before, I got to know Jamie in Japan. He has a great sense of humor, which is made even funnier by his thick West Virginia accent. At the time, he’d recently had a baby boy, and the way he talked about him made my heart melt. We had a great tour together that included a fun Juniors Tag Team Championship match against Jado and Gedo. At the end of the tour, Jamie gave me a big hug and thanked me for helping him. (Since then, he’s helped me a thousand times more than I’ve helped him, as I’ll explain later.)

I loved wrestling in New Japan, and when 2004 ended, I envisioned spending the rest of my career there—similar to the way Scott Norton had spent a majority of his—but it wasn’t meant to be. That December tour was the last time I worked for New Japan Pro Wrestling.

The beginning of 2005 looked a lot like my 2004: I wrestled every weekend on independent shows and had a New Japan tour booked for February. However, two weeks before the tour was supposed to start, I still didn’t have my visa. Simon and Hiroko, who were the ones that actually dealt with New Japan, didn’t know why it hadn’t arrived but got back to me about it the next day. They apologized and said I would be on the March tour, which I didn’t mind because my body could use the couple of weeks off.

Prior to the March tour, I continued to inquire about my visa, and Simon and Hiroko continued to reassure me it would be there anytime. Ten days before it was supposed to start, they told me I wouldn’t be on the March tour either. Admittedly, when it happened the second time, I grew frustrated because living in Santa Monica, it’s hard to get independent bookings at the last minute. Independent promotions have limited budgets, so flying an independent wrestler like me—whose experience also earned him a higher pay—from L.A. on short notice wasn’t within their finances, especially since they didn’t have a long time to promote it. I was able to pick up a couple of ROH shows and a Pro Wrestling Guerrilla booking because they were in the L.A. area, but that was about it.

April was a Young Lions tour for New Japan, so I knew I wouldn’t be on that either, but they claimed they wanted me in May for their Best of the Super Juniors tournament. In mid-April, the same thing happened yet again. I had no idea what was going on. New Japan always seemed happy with my work, and I had a good relationship with Simon and Hiroko; everything about this seemed suspicious. After this third disappointment, I decided to go back to England since, again, independent bookings were more difficult to come by. It wasn’t much money, but I knew I’d be wrestling and having fun, so I drove back to Aberdeen to leave my car there for the trip and prepared for my journey.

In early May, shortly before the Super Juniors tour, I got a call from Simon, who said that New Japan did indeed want me for that month’s tour, but because I was a last-minute addition, they would need to lower my pay by $500 per week. I told him thanks, but no thanks. Even with the pay cut, I would have made more money on the three-week New Japan tour than I would working the entire summer in England. It was one of the few times I made a decision in wrestling because I was angry and felt disrespected. I never found out exactly why all of that happened, though I later learned it had something to do with politics between the Inoki Dojo and New Japan. I was essentially a pawn in a larger struggle. As a result, I never went back to the Inoki Dojo or to New Japan, which is unfortunate because I loved both.

My second tour of England was much the same as my first back in 2003: lots of fun, stress-free wrestling, where I could further hone the “entertainment” aspect of my performance. Also, as on my previous trip there, it was kind of like I disappeared from the planet when I was in England. My cell phone didn’t work there, so other than trying to make a monthly call to my family (and that’s a very loose definition of “try”), I was pretty much incommunicado. Sometimes on rare days off, I’d go to the library to check my e-mail, and on one such occasion, I had a message in my in-box—from CM Punk, I believe, though I could be mistaken—citing a rumor that both WWE and TNA (Total Nonstop Action) were interested in Ring of Honor’s three top guys: Punk, Samoa Joe, and me.

I’d done a few enhancement matches for WWE earlier in the year and knew I was at least on their radar, because I was always given competitive matches rather than just getting squashed. After that e-mail, I became more conscious of getting to the library on days off.

Soon after, Samoa Joe signed with TNA, and they pushed him right away on TV. Punk went the other way and signed a developmental deal with WWE. I stayed in England for four months on this trip without hearing anything more about it. When I flew back to the United States that September, I kind of expected to be offered a deal by one of the two organizations, but when I turned my phone on, I didn’t have a single voice mail, and nobody from either company contacted me in the weeks that followed. (To be fair, I didn’t call them either. That’s that lack of ambition.)

I did, however, receive a phone call from Gabe Sapolsky, booker for Ring of Honor. He didn’t reach out to offer me a contract or a ton of money; his offer was something different: my first opportunity to be “the Man,” as Ric Flair often described it.

Gabe has admitted he never saw that potential in me at first. He thought I was a great wrestler but lacked the ability to be the guy the company was based around. He saw that trait in Punk, and he saw it in Samoa Joe, who had a nearly two-year reign with the ROH Title. Those guys were locker room leaders, and each of them had a unique charisma. Gabe saw me as a nice, quiet guy, content to just do my own thing.

With Punk leaving for WWE and Joe heading to TNA, Jamie Noble (known as James Gibson in Ring of Honor) won the ROH Championship in August 2005. But not too long after that, WWE offered Jamie a contract to return, which he took, and Gabe was out of options.

“You’re the guy we want to build around,” Gabe said to me. “But to do that, I have to know that you won’t leave for WWE or TNA, or be gone all the time on Japan tours.” I didn’t have any offers from those larger organizations and hadn’t heard a word from New Japan since I left for England, but there was definitely more to consider than that before accepting. Being the ROH Champion was a tough gig. They would rely on my matches to sell DVDs and bring people to the buildings. To go on last and send the people home happy was a considerable challenge because everyone was trying to have the best match on the card, and by the time you went out there, the fans had seen it all. Nonetheless, it wasn’t more than a few seconds before I agreed. I vowed I wouldn’t go to WWE and that I’d put all of my energy into ROH for at least one year. It was a huge opportunity, but I needed to raise my game.

At Glory by Honor IV on September 17, 2005, I beat Jamie Noble (competing under his real name, James Gibson) for the Ring of Honor World Championship. Even though we didn’t go on last, I knew we were the main event. Jamie and I wrestled our hearts out for over twenty minutes in front of the very appreciative fans in Lake Grove, New York. I always loved wrestling Jamie, but this was the first time we got to have that kind of match—the kind of match people would remember. When it ended, after Jamie ultimately tapped out to the cross-face chicken wing, the crowd erupted. He and I hugged, after which I grabbed the microphone and promised the fans that while I was champion, I wouldn’t even think of leaving Ring of Honor. Ironically enough, I missed the next two ROH shows—two of the biggest shows in the company’s history because they featured a rare appearance in America by Japanese wrestling legend Kenta Kobashi—because they took place on the weekend my sister got married. (To me, some things are more important than wrestling.)

My Ring of Honor World Championship win has always ranked very high on my list of accomplishments. They chose me to be the man, and that hasn’t happened very often in my career. It was one of the few times when it was decided I was going to be given the ball and get pushed into the top spot to carry the promotion.

Before I won the title, the ROH fans hadn’t seen me since May, when I had a shaved head and a long beard. When I returned, I came back clean-cut, with no beard and neatly trimmed hair. Whereas before I wore black, I came back wearing all maroon, gear given to me by William Regal. I even came out wearing a maroon jacket with AMERICAN DRAGON embroidered on the back. It was a more classic look, inspired by an older generation of wrestlers like Bob Backlund and Billy Robinson, symbolizing that I would be more of a sportsman and less of an “entertainer.” Soon I realized that was a mistake.

My very first championship defense was against AJ Styles, and our rivalry was based on a story about who of us was the better wrestler. We both wrestled on the aggressive side, but at the end of the match, fans were supposed to like both of us. We had a good match with a decent response from the crowd, but it wasn’t what a title match should be, as far as crowd reaction. The same happened with the next several title matches, none of which lit the world on fire. I knew I needed to change something or my title reign was going to bomb.

It wasn’t until I was in the ring wrestling Roderick Strong that I found the answer. The fans in Connecticut were fully behind Roderick, with a few of them jeering me. I started to subtly get more aggressive, then became less subtle about it. That kind of transition isn’t so strange in wrestling, but my thought process changed: I am the Ring of Honor World Champion, and this guy isn’t in my league. In fact, not only is Roderick not in my league, nobody is in my league—not anybody in ROH, not anybody in WWE. I am the best and I will prove it every night.

That night, after I beat Roderick, I cut a promo about being the “Best in the World,” and it stuck throughout my 462-day reign. It doesn’t sound that great now since people have heard both Chris Jericho and CM Punk claim to be “the best in the world” on national TV. But at the time, nobody had consistently made that claim in years. It legitimized me among the independent wrestling fan base, and I was then a top guy anywhere I went, against anybody I faced. It worked because it was boastful and gave me an attitude; it was also a rallying cry for the Ring of Honor fans. They believed ROH was producing the best wrestling in America. WWE was far too interested in entertainment, and that didn’t appeal to this audience, who wanted something grittier and organic. They wanted most of their action between the ropes, not on the microphone or in silly backstage vignettes.

Most of all, they wanted to believe that the wrestlers they watched at Ring of Honor events—at least some of them—were “better” than those appearing on TV programming of larger organizations, so I changed my character to appeal to that desire.

The night of that first match against Roderick was also the first in a series of experiments I was doing on wrestling finishes. A standard wrestling trope was that you beat guys with your “finisher.” Some guys have two, but very rarely do people have more than a couple of moves that they will actually beat guys with.

For the more astute fans, matches become more predictable: They know that even if a wrestler hits another with a big impact move, if it’s not his “finisher,” it won’t end the match. I wanted people to think that a match could end at any time. On top of that, though the hardcore fans at ROH very much appreciated wrestling, it was hard to get them to believe that any of it was legitimate, after so many years of WWE saying it was all “just entertainment.” We didn’t need people to believe the whole thing was real, though, just part of it.

Guys lose their tempers and sometimes things get real in the ring—most people never know it because it just seems like sloppy wrestling. My idea was to create a moment in which the audience would wonder if what they were seeing was actually real. The finish of the Roderick match was something that legitimately happened to us. One night after a show, a bunch of us were hanging out in my hotel room and Roderick was drunk, his behavior growing more and more irritating as he jumped all over the place while I was lying in bed. I told him to get out of the room if he was going to be annoying, so he charged and sprang on top of me. I immediately put Roddy in an omoplata shoulder lock with my legs until he screamed (it didn’t take long), and then I let go. Gabe was in the room and saw the whole thing. He thought it was awesome, and later that week, he told me he wanted that to be the finish in our upcoming match. I agreed, although only if Roderick wasn’t drunk.

So we did it. In the match, Roderick was chopping me so hard that my chest was bleeding. As lots of wrestling fans who’ve tried chopping each other know, it hurts. Chops make a loud, visceral sound, and people know they sting. So it wasn’t hard for fans to believe that with all the chops Roddy had given me, I was pissed off. Instead of the usual cavalcade of moves before the finish of a big match, we just started elbowing each other in the face really hard until Roddy nearly knocked me out. He went to jump on me and, just like in the hotel room, I instantly put him in the omoplata. Rather than the typical milking of the submission, Roderick tapped out almost immediately, rolling to the floor without selling anything. He was pissed off, I got up pissed off, and then I spit on him and said he was a “piece of shit.” People in the arena had no idea what had just happened. It looked as if, in the middle of a normal wrestling match, tempers flared and a fight broke out. That was exactly what I wanted.

Weeks later, our rematch had a different buzz about it, and Roderick had gained even more support from the fans. The entire match was aggressive and hard-hitting. Even though the scars hadn’t healed from the first match, he chopped me until my chest was bleeding again. Finally I beat Roderick by putting him in a crucifix and elbowing him until he was knocked out, an idea I got from a Gary Goodridge fight in UFC. The referee had to stop me from elbowing Roderick after he was knocked out, and, in one night, we created a new way a match could end in ROH: a referee stoppage. The fans didn’t understand it at first, and some were pissed off, but you have to take chances sometimes—and this one made my matches ahead much more interesting.

When I competed in Ring of Honor, my character was much different than how I’ve come to be known in WWE. Within WWE, I’ve constantly been portrayed as an underdog. In ROH, I wasn’t a small guy compared to the other guys; especially those last couple of years when I was the top guy, whomever I was facing was actually the underdog. One of the more popular things people would chant over and over again toward my opponent was “You’re going to get your fuckin’ head kicked in!” It originated in England for soccer and got popular for wrestling in Ring of Honor. My style was more technical wrestling, but brutal, incorporating a lot of MMA movements into what I did, like the repeated elbows or repeated stomps to the skull. Ring of Honor crowds saw me as a badass with a big beard and shaved head.

Ring of Honor opened up 2006 with a hot interpromotional feud with a company called Combat Zone Wrestling (CZW). Each organization had its own passionate fan base, which really contributed to the success of this rivalry. CZW was known for doing extremely violent wrestling that incorporated a great many weapons in matches. By this point, using things like tables and chairs was commonplace in mainstream wrestling. CZW took things a step further. Instead of just putting somebody through a table, they would put somebody through a barbed-wire table that was on fire. They would hit people not only with chairs but with things like long fluorescent light tubes that shattered on impact. I even saw a guy turn on a weed whacker and use it on his opponent. Their fans loved it.

Most of our fans, however, thought it was garbage wrestling and that the CZW wrestlers were vastly inferior to the regulars of Ring of Honor. On the flip side, a lot of CZW fans found technical wrestlers like me boring, and they didn’t like what they perceived to be Ring of Honor’s elitist attitude. With both companies based in Philadelphia, it was a perfect rivalry.

It started off with some CZW wrestlers invading an ROH show and Chris Hero, one of their promotion’s top performers, challenging me for the ROH Title. In return, we invaded a CZW event when we were running a show across town the same night—the first time I’d ever been in the famed ECW Arena in downtown Philadelphia. A bunch of wild brawls broke out, including one in which ROH wrestler BJ Whitmer had a sheet of paper stapled to his forehead. The fans of each company were white-hot for the feud, leading to my match with Hero for the ROH Championship in Philadelphia on January 14.

One of the hardest things in wrestling is getting the fans to care. I’ve had a lot of good technically sound matches in which nobody cared because there was nothing at stake, just another match where it didn’t matter who won or who lost. That wasn’t the case with me and Hero at Hell Freezes Over. We had a split crowd—half CZW fans, half ROH fans—who were excited as hell for this match and couldn’t wait to cheer on their respective guys. You could absolutely feel the electricity during our entrances. When we started off wrestling, trying to prove who was the better wrestler, the crowd was really into it. But then we kept wrestling … for almost thirty minutes. The more we wrestled, the more the crowd became disinterested. The fans wanted a fight, and what ended up being a long, scientific wrestling match should have been a hate-filled brawl.

You need to know when to wrestle and when to fight. That night in January 2006 was a time when I chose the wrong option. I’d say that match was my biggest failure as Ring of Honor Champion.

In 2006, ROH made a great business decision by running shows in WrestleMania’s hosting city the two nights prior to WWE’s mega-event. WrestleMania brings in dedicated, hardcore wrestling fans from all over the world every year, so while they were all in town, even people who’d only heard about Ring of Honor on the Internet could come watch a show. It led to big business for ROH, and they’ve done it every year since.

That year, WrestleMania 22 was in Chicago, one of the cities with the most ROH fans. Our first show, on Friday, had more than a thousand people, and they seemed to really love it, with the exception of how long the show was. Gabe wanted me and Roderick Strong to tease an hour-long draw but have me beat him right before the sixty-minute time limit. It was a great idea, but the problem was that the show started at 8 P.M., and by the time Roderick and I went to the ring, it was already after midnight. The full show had already been going on for four hours! The crowd was tired, and I could see people leaving midway through our match. (I couldn’t help but think, I wish they would have done that for the Aries match.) Yet we got through it and the crowd gave us a polite applause after we wrestled for fifty-five minutes, ending the show at 1 A.M.

The following night was way better, and we had a record-setting attendance for an ROH show, with over 1,600 people. I wrestled former WWE, WCW, and ECW star Lance Storm, who was coming out of retirement, for the ROH Title in a fun match. Nobody in the crowd left during it, so I considered that a huge success.

When I’d returned from England a year before, I’d moved back in with my mom and enrolled in Grays Harbor Community College in Aberdeen for the fall quarter. Now, in the middle of the winter quarter, Ring of Honor presented me with another opportunity.

I had a chance to go from student to instructor (again) when they offered me the role of trainer at the Ring of Honor School they’d opened in Philadelphia. When it initially opened, the wrestling school’s first trainer was CM Punk, but he got signed by WWE. Austin Aries was the next trainer, but then he got signed by TNA. I’d be the third trainer since the school’s inception, and despite knowing I wasn’t the best trainer while in APW, I assumed that I would be better some four years later after amassing so much more experience.

My apartment would be paid for, and I’d also make a commission on any students who attended. Besides that, my sister had moved to a place in Pennsylvania about ninety minutes from where I’d be living. So I finished the winter quarter at Grays Harbor, and in April 2006, I drove the nearly three thousand miles from Aberdeen to Philly.

Much to my chagrin, I was no better at training people to wrestle in 2006 than I was in 2002. Nobody stuck with the class more than three weeks. I constantly asked my students to come in with things they wanted to work on, and they rarely would. I don’t chalk that up to them being complacent, though; it was still the problem of me not being able to inspire them. In a coaching role, inspiring people to want to get better is often more important than teaching them techniques. And I was no good at inspiration.

In summer 2006, I had my first encounters with one of my all-time best opponents, an English wrestler named Nigel McGuinness. Outside of the ring, I enjoyed being around Nigel because he was superintelligent and had a great self-deprecating sense of humor. He and I became exceptionally good friends, and the tremendous chemistry we developed carried over into the ring, where I had some of the greatest matches of my career against him. The most memorable bout was at a show called Unified, which was Ring of Honor’s first event in England.

Our contest at Unified was a unification match to merge the promotion’s top two titles: the ROH World Championship and the Pure Championship—which, created in 2004, was essentially the same as WWE’s Intercontinental Title. In Ring of Honor, the Pure Title and its defenses had unique rules, like limited rope breaks and no punches to the face; plus, the championship could change hands on count-outs or disqualifications. Nigel was the Pure Champion for almost a full year and had even beaten me, the ROH World Champion, by count-out in Cleveland, Ohio, using the distinct rules to his advantage. Nigel was traditionally a bad guy, but that night in Liverpool, he was incredibly popular with his fellow Englishmen. The crowd was passionately behind Nigel, cheering him on the entire match and booing me every chance they got.

At one point during the match, I grabbed Nigel by both arms and pulled him into the ring post headfirst, causing him to bleed. It was Nigel’s idea, but he wasn’t sure if he could get the post to bust him open. I suggested blading, but he wanted to do it the hard way. We decided I would pull him in three times, and if he didn’t bleed, we’d stop. After three attempts, he wasn’t bleeding, but he yelled at me, “One more time!” This time, he slammed his head really hard into the post, and the blood started pouring like crazy. We continued on—the blood adding more and more drama—until finally I did the same thing to him that I did to Roderick. I put him in a crucifix and elbowed him until he was knocked out.

The match was great and sold a ton of DVDs, but looking back, the ends didn’t justify the means. Due to the shot to the ring post, Nigel had an enormous hematoma on his forehead, a huge knot of blood that slowly drained down to his eye. He ended up with serious concussion problems because of things like that, although that ring-post spot may have been the most visual example. We’ve all done a lot of stupid things in wrestling. Some end up being worth it, others not. Even though it was a great match, it wasn’t worth what Nigel ended up paying for it.

In August of 2006, I had three one-hour matches within a two-week period, two of them on back-to-back nights. It used to be that the NWA World Heavyweight Champion toured all over the world and worked with the top star in every territory. Sometimes he would win clean, but oftentimes, because the champion would be moving on and the local star would continue wrestling in the area, they would wrestle to a sixty-minute draw. Lou Thesz did it. Harley Race did it. Ric Flair did it. I looked at it as my chance to do it.

Unfortunately, wrestling fans don’t have the patience they used to, and, just as unfortunately, I am not as good as my predecessors at going sixty minutes. None of the hour-long matches were bad, they just weren’t epic in the way you want it to be. The first one was against Samoa Joe in New Jersey, and I cannot remember a single thing about it. The second hour-long match was against Nigel in St. Paul, Minnesota; it was probably the worst of all the matches Nigel and I had against each other, and he got another concussion, to boot. Everything about it was regrettable. The following night, I wrestled Colt Cabana in his hometown of Chicago—the third and most memorable of the sixty-minute matches, but not necessarily because it was good.

Roughly five minutes into the match, I was pushing Cabana into the ring ropes and, as he came off them, I’d catch him with a headbutt to the stomach. We did it a few times, until he stepped aside on the last attempted headbutt, sending me crashing to the floor. I had previously fallen that exact same way well over a hundred times, and never once do I remember even stubbing my toe. This time, however, I missed posting on the apron with my hand as I fell, and I crashed down, shoulder first.

I knew something was wrong, so I took my sweet-ass time getting back into the ring, hoping I could shake it off. It didn’t help. I was lucky I was in there with Cabana, because he can be entertaining without throwing you all around. Still, everything I did hurt. At one point, I was going to give him a diving headbutt off the top rope, trying to gut through it, though I knew I was just going to make it worse. I could have stepped down, but I knew I would look stupid, so instead, I jumped off the turnbuckle and stomped Cabana right in the chest, way harder than I intended. He let out this guttural sound on impact and had a hard time breathing for the next minute, but we were able to get through the match.

After I flew back to Philadelphia the next morning, I went to the hospital. The doctor told me I had partially torn two tendons and, more distressingly, separated my right shoulder—the same one I separated in 2000 and the same side I’d have problems with later on in my career.

I had bookings over the next two weeks, which, for the first time in my career, I had to cancel due to injury. In three weeks, I was scheduled to wrestle Japanese star KENTA (now Hideo Itami in WWE) for the ROH Championship in New York City. Everyone knew I was hurt, because Ring of Honor had covered my injury on their Web site. Given my reported condition and how KENTA was positioned around that time, most people expected him to beat me.

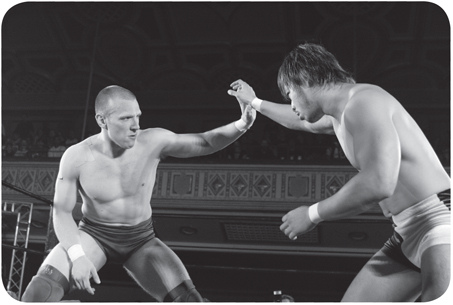

Bryan faces Japanese star KENTA for the ROH World Title in NYC, 2006 (Photo by George Tahinos)

In American wrestling, if somebody has a legit injury, you try to mostly stay away from it to avoid further injury. For example, with my shoulder hurt, someone might attack my leg. In Japan, if the fans know you have a real injury, the wrestlers almost feel obligated to treat it like a legitimate fight and attack an injured body part to avoid insulting the intelligence of the fans. KENTA and I took the Japanese route: Instead of protecting it, KENTA kicked the shit out of my right arm the entire match. My girlfriend at the time was in the crowd, and she was literally crying in the middle of the match, with one of the other wrestlers trying to settle her by telling her I was OK. But I was more than OK; I felt alive. With the emotion of the crowd, the physical intensity of the match, and the story that was told throughout, it is undoubtedly one of my favorite matches of my career. When I put KENTA in Cattle Mutilation and he tapped out, the crowd erupted. It was one of those times when the pain was worth it.

After the KENTA match, I did my first tour of Japan for Pro Wrestling NOAH, basically, so that KENTA could get his win back in front of the Japanese audience. I did my best, but with my shoulder getting progressively worse, I focused on trying to make it until Ring of Honor’s biggest show of the year, Final Battle. At that event on December 23, 2006, a wildly popular wrestler named Homicide beat me for the Ring of Honor World Championship in front of a sell-out Manhattan Center crowd, our second show in the building. My shoulder was a wreck, but Homicide and I tried to pull out all the stops to make his title win as memorable for the fans as it could be. In the end, Homicide hit me with his Cop Killa, one of the coolest-looking moves in wrestling, then pinned me, as the crowd went nuts. My 462-day title reign was over.

In retrospect, I was proud of the work that I had done as champion in Ring of Honor, and it made me grow as a performer. It was the first time anybody had chosen me to be “the Man”—the only time, really—and I can’t thank Gabe, ROH, and the ROH fans enough for giving me the opportunity to be the guy to carry the promotion.

After losing the ROH World Championship in December, I moved back to Aberdeen from Philadelphia. Ring of Honor and I agreed they needed a new trainer for their wrestling school and I needed to rehab my shoulder. While focused exclusively on getting healthy, I didn’t wrestle again for over three months—the longest time I’d ever taken away from wrestling.

When I was healthy enough to return to the ring, I was thrown right into the fire. Despite not being my best during my first Japan tour with Pro Wrestling NOAH, the promotion brought me back for a four-week tour in April of 2007. With my shoulder healthy and my body feeling rejuvenated, I made a much better showing after shaking off the early ring rust.

On that tour was the first time I met Ted DiBiase Jr., the son of the Million Dollar Man, a WWE Hall of Famer. Teddy had only competed in sixteen matches before he went on the tour, which reminded me of my first tour with FMW. The big difference was that Teddy was way better this early in his career than I was the first time I went to Japan. As far as having a natural instinct for wrestling, Teddy might be the best I’ve ever seen. There were definitely times when he showed his inexperience, but 90 percent of it he did really well, and I was impressed. Not only that, but he was also fun to be around. With his Mississippi accent and his southern hospitality, it was hard not to immediately like the guy. Soon after this tour, Teddy signed to a WWE developmental deal, and I couldn’t have been happier for him.

By May 2007, it had been over five months since I had wrestled for Ring of Honor, and I was excited to come back, especially because they had made some major changes since I’d left. In early May, ROH announced they had signed a deal to produce bimonthly pay-per-view events. Live pay-per-views were beyond ROH’s budget due to the substantial expense of satellite time, so they taped the shows, edited them, and then put them on pay-per-view a few months later. These events were another way to expand the audience, on the assumption that fans who might not want to buy a DVD might be more willing to order a pay-per-view. In addition to the expansion to pay-per-view, for the first time, ROH started to sign talent to contracts in order to make sure the guys they built the promotion around wouldn’t leave for WWE or TNA. I happily signed a two-year deal.

The inaugural pay-per-view taping, called Respect Is Earned, featured my return to ROH, and it was back at the Manhattan Center on May 12. Everyone in the locker room was amped up for the opportunity to be on pay-per-view, including me. The fans were really excited, too. I wrestled in the main event, teaming with a 350-pound NOAH wrestler named Takeshi Morishima, who’d beaten Homicide for the ROH World Title, to face Nigel and KENTA. After Morishima and I won, he dumped me on my head for being a dick, and then Nigel clotheslined Morishima in the face, thus creating two potential challengers for the ROH Title. I thought the show was an excellent introduction to the promotion for people who had never before seen our wrestling. It established who all the characters were, who the rivals were, and why the fans should care.

The following month, Nigel and I wrestled each other in the main event of the second ROH pay-per-view, Driven 2007. Toward the end of the match, Nigel and I started headbutting each other without putting our hands up for protection, as if we were two rams butting heads to display our dominance. In the middle of the exchange, I was cut wide open at the top of my hairline and blood poured down my face. The fans loved it.

After I won, fellow wrestler Jimmy Rave took me to the emergency room, where they closed up the cut with staples. I finished up at the hospital just in time to catch my flight home, and I felt good knowing that Nigel and I had put on a great match that the pay-per-view audience was going to love. I had no idea what was about to transpire that would shake the wrestling world for some time.

On Monday, June 25, 2007, I was in the car driving home to Aberdeen from Olympia, Washington, after two hours of kickboxing and jiu-jitsu. I was exhausted and content with about fifteen minutes left in my hour-long ride when I got a call from my friends Mike and Kristof. They were watching Monday Night Raw, and WWE had just announced that Chris Benoit, his wife, Nancy, and their seven-year-old son, Daniel, had been found dead in their Atlanta home. I went straight to Mike and Kristof’s apartment, and we watched Raw together in shock. Chris Benoit had been one of my favorites, and someone I’d patterned my career after. He had wrestled all over the world, getting better everywhere he went, and by the time he made it to WWE, he was one of the best wrestlers on the planet. Beyond my professional admiration, the few times I met him, he was very kind to me. I was crushed.

WWE canceled the live show and ran a three-hour tribute to Chris that night. They showed some of the biggest moments of his career, interspersed with video packages and interviews with WWE Superstars who shared their very personal memories of him. It was an emotional program to watch, and I ended up leaving Mike and Kristof’s halfway through.

The next day, horrific details started coming out, and what was eventually discovered was that Chris had killed both his wife and son, then hanged himself. The Benoit double murder/suicide horrified people, and media outlets picked up on it right away. People tried to figure out why it happened, with speculation that it was caused by “roid rage” or because Chris and Nancy’s marriage was falling apart. To this day, there is no definitive reason for why it happened and there probably never will be. But investigations led to the Sports Legacy Institute performing a series of tests on Benoit’s brain, which according to Dr. Julian Bailes “was so severely damaged it resembled the brain of an 85-year-old Alzheimer’s patient.”

The type of brain damage Benoit had is known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which researchers believe is connected to having multiple head injuries. CTE’s most common symptoms include depression, cognitive impairment, dementia, Parkinsonism, and erratic behavior, and many experts believe CTE was a significant contributing factor in the Benoit tragedy. Multiple NFL players who committed suicide were found to have CTE as well, and the condition became a major news story in itself. There was a palpable shift in the nationwide awareness of the dangers of head injuries and concussions.

Chris Benoit popularized a wrestling style that was hard-nosed and aggressive, with lots of explosive suplexes and diving headbutts off the top rope. Looking back on it, you can see how easy it would have been for him to have multiple undiagnosed concussions. It was the same style that influenced me and many wrestlers of the new generation; it was action-packed and exciting, with an element of physical violence that was believable. That kind of wrestling is what made me and many of the other guys in ROH stand out from the pack.

When Nigel and I did the headbutts in June at the Driven pay-per-view, it seemed awesome. Two warriors ramming each other in the head until one of them bled. It made for a great visual, and spots like that showed our love for the business and our willingness to do anything for the fans. But when the match finally aired on pay-per-view on September 21, with all the awareness around the dangers of head injuries, it no longer seemed awesome. It seemed stupid and it seemed reckless, which made people question why they supported something that endangered the long-term health of the performers. In hindsight, Gabe told me, he wished they’d never aired it.

After the Benoit tragedy, the perception of wrestling became so negative that many fans no longer cared to watch—especially a company like Ring of Honor, which heavily featured a style similar to the one Benoit helped to popularize. Initially, ROH pay-per-views garnered around ten thousand buys, which was phenomenal for a company whose only exposure was through word of mouth and the Internet. However, with each passing pay-per-view, buys dropped, and after the six-event deal was up, ROH chose not to renew it.

The paradigm of how we should be wrestling was shifting. Some people accept new paradigms quickly. In this instance, I was not one of them. Despite all the concussion awareness and my own acknowledgment of certain dangers, I refused to tone it down. I stopped the aggressive headbutting, but I kept everything else about my in-ring performance the same. In mid-2007, I ruptured my left eardrum during a wild, open-palmed exchange with KENTA in which one errant shot caught me in my left ear. I never got it fixed, and even now I don’t hear as well on my left side. Later in the year, I detached my retina, in another example of my own stupidity.

Takeshi Morishima was still the ROH World Champion when I was booked against him that August at Manhattan Mayhem. At 350-plus pounds, Morishima was a giant compared to your standard ROH star, and, working in Japan, he was used to wrestling bigger guys (whom he had no problem smashing around). In Ring of Honor, Morishima had some great title matches against stars like Claudio Castagnoli (now known as Cesaro in WWE) and Brent Albright, but he proved to be a gentle giant, of sorts. In title matches with smaller ROH wrestlers, he tended to use a lighter touch, almost as if he were afraid of hurting us.

When Gabe booked Morishima and me in the championship match at the Manhattan Center show, we both agreed I needed to do something to turn the big man into the monster he was when he wrestled larger opponents. If he handled me gingerly, it wasn’t going to work. I decided—because I’m somewhat of an idiot—that the best way to do that was to piss him off.

Prior to our match, I stressed to Morishima to treat me as if I were a heavyweight in NOAH. He smiled gently and nodded his head, but I don’t think he understood. We structured the match so it would be based on me trying to stick and move, not wanting to be crushed by a man that size. My “sticking” comprised kicking his leg; Morishima would attack, and I’d move out of the way and use a Muay Thai kick to the leg. At first I was kicking him normally—hard yet safe—but he wasn’t being very aggressive. So then the leg kicks got harder. With the first really hard one, I could tell he thought it was an accident, but as I kicked him harder in the leg, I could see the expression on his face change. He was starting to get mad. I kept with it and kept with it, and when he finally caught me in the corner, he was a giant, pissed-off Japanese monster.

He started clubbing me to the side of the head with each hand in rapid succession, a style of punching popularized by another large wrestler named Vader. Usually when he’d do it to the smaller ROH wrestlers, it would look light as a feather and phony as could be. These were different. In the middle of the flurry, one blow caught me directly in the eye and I dropped. My cheek started swelling, and everything in my left eye was blurry. We wrestled another ten minutes after that, and I was still able to do things like the springboard flip dive into the crowd, but my eye was throbbing and it worried me. I had never experienced anything like it. Morishima continued to bring it in a way that made the match exactly what it needed to be. Afterward, Morishima—a truly nice guy—felt horrible and apologized what seemed like a hundred times, despite the fact that he was limping and had one long, giant welt on his leg from the low kicks. I told him it wasn’t his fault and that he did a great job, which he did.

The backstage doctor told me I needed to go to the emergency room right away, and it was at the hospital that I found out I had not only fractured my orbital bone but also detached my retina. Two days later, I underwent laser surgery to have it reattached. I was instructed to take it easy for at least a month, if not longer, to permit my eye to heal. I was told to avoid flying because altitude changes could aggravate it. I had to wear an eye patch to keep the light out and just generally be careful to not put any pressure on it. But other than a little bit of pain from the fracture, I felt fine. So, like an idiot, I demanded to keep my scheduled rematch with Morishima three weeks later. Why? Because I thought it would be a great story.

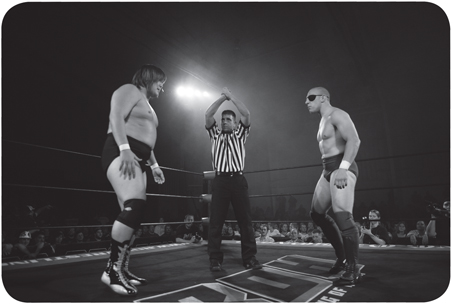

The rematch with Morishima in Chicago went well, despite the doctor’s recommendation. I wore the eye patch—more for the visual than for actual protection, of which it provided very little. In another one of my dumber ideas, for the finish, Morishima gave me repeated clubbing blows to my damaged eye until I sold being knocked out. The 350-pounder made sure I was safe, and luckily I escaped the match without further damage (though I still have some vision problems in my left eye).

Eye-patched Bryan faces Takeshi Morishima in Chicago, 2007 (Photo by George Tahinos)

In 2007, Morishima and I had four matches, and Gabe and I worked together on the story to make sure each showdown built upon the last. I had also learned from the Chris Hero debacle the year before. After Morishima attacked my eye in Chicago, it became a violent and bloody feud. The third match was under twelve minutes and ended in a disqualification because I repeatedly stomped Morishima in the testicles. Usually Ring of Honor crowds hated disqualifications, but they cheered this one because it was a moment of vengeance against Morishima, who, in their eyes, got what he deserved.

My final match of the year against Morishima was taped in December for a pay-per-view called Rising Above, and given the previous match’s disqualification outcome, this one was held under “relaxed rules.” At under six minutes, this was a short, violent sprint. We were going to war. I bled after Morishima threw a table at my head, and somewhere toward the end of the quick match, one of the Japanese giant’s clotheslines knocked me out. When I watched it, I could see the shift in Morishima’s attitude from wild monster to concerned colleague. Our referee, Paul Turner, didn’t know what to do; I was out of it, and this was for pay-per-view. He was in a tough position as the official: He didn’t want to mess up the booking, but he also wanted to protect me as a performer if I was hurt.

The next thing I remember was being on Morishima’s back and using the opportunity to elbow the shit out of his face. The big man didn’t have much problem getting back to being a monster after that. The calamity continued as we both attacked the referees who were trying to break us apart. The announcer declared the finish as a double disqualification, but they couldn’t ring the bell because I’d taken it and attempted to gouge out Morishima’s eyes with the bell hammer, while I wildly screamed out that I was going to “blind this son of a bitch!”

After the match, I was in bad shape. My head hurt, and I couldn’t shake the dizzy feeling. Unfortunately, on that same show, Nigel—who by this point was the ROH World Champion after beating Morishima—received a concussion as well when the back of his head hit the barricade in a match against Austin Aries.

Earlier in the year, Nigel had told me I needed to read former WWE wrestler Chris Nowinski’s book Head Games: Football’s Concussion Crisis, which discussed the dangers of concussions in football and other contact sports. It specifically talked about people getting early onset Alzheimer’s disease and dementia due to head injuries. Reading it scared the shit out of both me and Nigel. One of the things Nowinksi emphasized in the book is that it takes time for the brain to heal and that in order to prevent long-term damage, it’s important to not rush getting back into action after a concussion. Of course, in almost all contact sports, acknowledging that you are hurt and that you have to recover goes against the ingrained mentality. Wrestling is no different.

The following night at the Manhattan Center, Nigel and I were supposed to be in big matches, but we both knew we needed to take the day off. Nigel, smartly, did. I, however, did not. I wrestled over twenty minutes in a four-way elimination match in the semi-main event. My head wouldn’t stop pounding for the next several weeks.

Despite moments like this, I loved being an independent wrestler. One thing I really enjoyed was consistently being able to wrestle new people. A lot of times, I’d go to a show and not know a single person there, including the person I was scheduled to wrestle. Sometimes I’d show up and someone I hadn’t seen in years would be there, which would make my day.

On one occasion, I was booked for a rare Wednesday show in the Midwest. I flew from Seattle to Chicago, then had a two-hour drive to the small town I wrestled in that night. My flight was heavily delayed, which set me back a bit in getting to the show on time, so I called and spoke with the promoter. Given my expected arrival time, it became clear that I was going to end up going straight from the car to the ring for the main event. To make matters more interesting, I’d never wrestled my opponent before, and I wasn’t sure if I’d ever even met him. I was also going to need to get changed in the car, and in the middle of winter, it was pretty darn cold to be half-naked in your vehicle.

I pulled into the parking lot a solid three minutes before my music was set to play. I walked into the lobby of what appeared to be a VFW hall and stood there in, essentially, my underwear until it was time to go. I borderline dreaded doing the match, because there are a lot of horrible, unsafe wrestlers out there, and I hadn’t even talked to the guy I was wrestling by the time my music hit, as I walked to the ring from where the fans came in.

What happened next was a surprise. Without having even spoken, my opponent and I wrestled a good basic match. The longer we went, the more impressed I was. I was a relatively big star on the independent scene by this point, but he didn’t even seem nervous. Quite the opposite, really: He was confident that he knew what he was doing and confident that what he was doing was good. His name was Jon Moxley, and he’d go on to become better known as Dean Ambrose in WWE.

I had another surprise in early 2008 the first time I wrestled Tyler Black, who is also now in WWE as Seth Rollins. Rollins had come into ROH a couple of months prior to our collision, mostly participating in tag matches and even winning the ROH Tag Titles. I had seen his matches, and I respected his athletic ability and poise in the ring. His trunks were too small, but I could look past that. I really looked forward to our match. Truthfully, we needed some new guys fans would accept as main-event talent in ROH, and Gabe thought Rollins had “it.”

Gabe knew what he was talking about. In the ring that night, Rollins made an impression on me and the entire ROH crowd. Even though we weren’t in the main event, they titled the DVD Breakout because of Rollins’s performance in our match, and I was happy to be a part of it. After that, he and I ended up having a series of matches, my favorite of which took place in Detroit. He gave me a powerbomb into the turnbuckle and the whole thing broke, adding chaos and unpredictability to the match. Instead of getting flustered, he improvised, and that match was one of the best I had that year.