FRIDAY, APRIL 4, 2014—5:23 P.M.

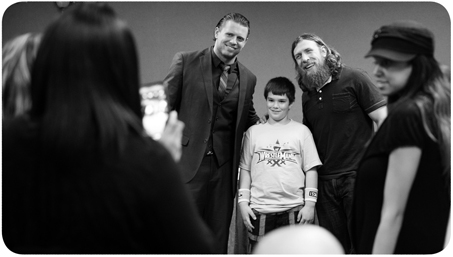

It’s awkward, at first, to see Daniel Bryan and the Miz seated so far apart—almost intentionally—at a conference room table just prior to meeting the ten winners of the WrestleMania Reading Challenge. The former NXT Pro and Rookie pair has a turbulent history, dating back to Bryan’s WWE debut in early 2010. Yet Miz and Bryan keep it more than cordial and even chat about the “Yes!” Man’s upcoming marriage.

Recently wed to former WWE Diva Maryse, Miz asks the right questions and shares something of a “bro” moment with Daniel at the table. “The Awesome One” then switches gears to talk shop, specifically WrestleMania. The NXT connection raises an interesting truth about the competition’s first season.

“When I first heard about NXT, I thought, ‘I’m a ringer for this, right?’ It turned out that it wasn’t the case at all,” says Bryan, who finished with a record of 0-10 under Miz’s tutelage. “By the end, I saw NXT’s headline stars as Wade Barrett and David Otunga—those were the two guys ‘they’ really liked out of the group. I did not foresee me being the first one of us to main-event WrestleMania.”

The unexpected “bro-down” ends as the Reading Challenge sweepstakes winners rally for their private Superstar signing in the room next door. The anxious young readers light up when both Daniel Bryan and the Miz make their entrance. One girl repeatedly squeaks, “OhmygodDanielBryan!” until he comes over to meet her.

“You want to inspire curiosity and inspire kids to be able to learn on their own,” Bryan says. “Anything you can do to get them to read as many things as possible, that’s just all the better. It’s a step forward.”

The winners line up for autographs and interrogation by Miz, who demands to know what book each youngster read to win the gift of his presence. Bryan turns the tables on the Awesome One moments later when Miz tries to start his own mock “Yes!” chant. Of course, Miz brushes off the response by this very exclusive crowd, but does acknowledge Daniel Bryan’s big match at WrestleMania, actually encouraging the kids’ cheers for his former NXT Rookie. Read between the lines of the Miz’s message and discover what might signify that Bryan has the support of the WWE locker room.

When WWE offered me a contract, I came in with low expectations. Several of my friends had wrestled in WWE and expressed their frustration with the lack of opportunities. Brian Kendrick actually quit the company in 2004 because he was so unhappy there, then came back, only to get fired before I signed. Colt Cabana spent nearly two years in the developmental system, the whole time only getting a couple of appearances on TV. The only independent guy at that point who had had any major success was CM Punk.

I also knew I had to change my style. I was used to wrestling twenty minutes every night in matches that made me popular with the independent wrestling fans. Most WWE TV matches are under five minutes. If you’re not winning the short match and you don’t get interview time, it’s hard to establish yourself as a character, much less get the fans to care about you.

Wrestling longer matches always challenged me, both mentally and physically. It inspired me to be more creative, which was important because wrestling is my primary artistic outlet. It didn’t boost my confidence at all when William Regal warned me, “Your wrestling career is what you did before this. Anything after is just a bonus.” I tried to look at it that way and told myself not to expect much; just come in, save money, do my best with whatever I was given. That attitude has served me well through the dips I’ve had with WWE. Still, when you love something so much, it’s difficult not to get a little frustrated.

One of my early frustrations, before WWE even knew what they wanted to do with me, was the issue of my name. I’d always been known as the American Dragon, but sometime in 2002, Ring of Honor booker Gabe Sapolsky told me he thought we should start using my real name as well, so it didn’t sound so much like a cartoon. I finally stopped wearing the mask at that point, so “the American Dragon” could just become more of a moniker. I liked the idea, and it didn’t take very long for me to be booked as Bryan Danielson almost everywhere I went, with two exceptions: New Japan (they didn’t want to confuse fans to whom I was introduced with this name during my first Far East visit) and All Star Wrestling (England was the last place where I still wrestled under mask to make me more kid-friendly).

However, before I started in WWE, John Laurinaitis called to inform me that I needed to come up with a new name, something WWE could license and own. When he told me it couldn’t be my real name, I argued that I had a decent following as Bryan Danielson and that a lot of guys in WWE used their real names, including John Cena.

“Well, we don’t do that anymore,” he said. He wanted me to come up with a list of ten names.

The first person I called was William Regal, whom I asked for some input. We both liked the name Buddy because it was fun and it was my dad’s name. We next came up with some absurd last names to go with it, most notably Peacock, based on an English wrestler named Steve Peacock. I thought of using my middle name, Lloyd, so that went on the list as well. Then Regal brought up the idea of using Daniel because he thought it was a strong name. With that, a lightbulb went on in his head, and he came up with the name Daniel Bryan. Regal thought it would be a great idea because anybody who’d heard of me on the independents would easily be able to tell that it was the same guy. It sounded weird as I said it, but all the names sounded weird except my own anyhow. I put it on the list, along with Buddy Peacock and my favorite, Lloyd Boner.

After I was officially signed, WWE just told me to wait and they’d call me when they were ready to use me. So for two months I waited in my rented room in Las Vegas, spending my time kickboxing, grappling with Neil, and trying to get in the best shape possible. During that time, WWE never contacted me or informed me of any plans. I wanted to be proactive—especially while I was receiving my first weekly paycheck in years—so I called them every two weeks to check in and see if they needed me to do anything.

In December, I traveled home to Aberdeen for Christmas. Thinking there was no way WWE was going to call me up until after the first of the year, I indulged in ten days of Christmas gluttony. Sugar cookies, pumpkin cake, cinnamon rolls. Nothing was off-limits. That, of course, was when WWE called: the Saturday after Christmas.

To put it mildly, I was concerned. After eating all those sweets and barely working out for ten days, I felt like the fattest man alive. How much damage one can do in that amount of time is debatable, but it didn’t matter, because it affected my confidence. To make matters worse, I was still ailing from my third staph infection of the year. Plus, I hadn’t wrestled in months—a critical detail since, as the old wrestling saying goes, “The only thing that can get you in shape for wrestling is wrestling.”

When I got to the show that Monday, I was actually relieved to learn I wasn’t doing something to air on TV. I wrestled Chavo Guerrero in an untelevised match before the show. That match against Chavo was only the second time I’d ever gotten “blown up”—a phrase used in wrestling for when someone gets really tired in a match, to the point that it affects performance—in my ten-year career. The first time was my forty-minutes-plus match with Paul London in 2003, when I weighed my heaviest at 205 pounds. With the combination of eating horrible food, not wrestling for months, and my nerves, by the end of the seven-minute match with Chavo, I was sucking wind. Everyone told me it was good, but I didn’t feel my best. And if I was going to debut on TV, nothing less than my best was acceptable.

With that in mind, I asked to go spend a week down at FCW, WWE’s developmental program in Tampa, to shake off the ring rust and get back into wrestling shape. After only a week there, where I mainly wrestled Low Ki, I felt infinitely more confident. My plan was to ask to go there one week each month until they were ready to have me start on WWE programming. But right before I was about to leave Florida, seven other guys and I were pulled into an office by the trainers, Dusty Rhodes, Norman Smiley, and Tom Prichard (Dr. Tom). They gave us the good news that we were all being called up to TV. WWE was debuting a new show called WWE NXT, a hybrid of wrestling and reality TV that was going to replace the ECW program that aired on Tuesday nights. They didn’t have a lot of details, though we were told it would be some sort of competition/reality show. At first it didn’t feel real, but the next day, they had us shooting all sorts of pictures and videos for the show. We were all excited for the opportunity, especially some of the guys who had spent years in developmental without getting their break.

The way they explained it to us, we would only wrestle on Tuesdays each week, and there was no way all of us could wrestle every show. I wanted to stay sharp and wrestle more frequently, so I talked to Dr. Tom and made the decision to move down to Florida so I could wrestle on the FCW shows as well. I drove the 2,300 miles from Vegas to Tampa in three days, which included a minor breakdown in Texas that set me back some hours. I got there just in time to move my stuff into a room I rented from Evan Bourne, then, not long after, we all flew out for the first NXT taping.

Shortly before the premiere on February 23, 2010, we were given a little more info on the show. We were going to be called “Rookies,” and we would each have a “Pro,” somebody who had been in WWE for a while and was assigned to teach us the ropes in the big leagues. WWE revealed the Pro and Rookie pairings online, which is how I found out my Pro would be the Miz. Even though the whole thing was fiction, the fans who followed me on the independents were outraged. I had years of wrestling experience and had become relatively well known as an excellent wrestler, whereas Miz had way less experience and struggled with credibility among the hardcore audience. Originally I wanted Regal to be my Pro because of our history, but I quickly realized being paired with Miz gave me a built-in story.

We had an interesting dynamic because Miz was everything I wasn’t. He was good on the microphone and carried himself like a star. We both thought the concept of Miz—this arrogant, overbearing Hollywood egotist—trying to turn a bland independent wrestler into a WWE Superstar would be a great story to tell. I even tried to make myself look more generic to fit in. I cut both my beard and my longer hair and avoided using my nicely designed ring gear, instead wearing plain maroon trunks and gear. As it turned out, WWE decided not to leverage any of that detail in the story, and I just made myself look uninteresting. Chalk that up as a lesson learned.

Initially I felt lucky to have that entertaining contrast with my Pro, but I was also fortunate that Miz actually wanted to be there participating in NXT because, when we came in, most of the other Pros didn’t. At the time, WWE Superstars didn’t typically work on both Monday (Raw) and Tuesday (SmackDown). You were typically on one or the other, not both. The selected Pros who were used to going home on Tuesday after Raw were pissed because they had to spend an extra day on the road, and the ones who were there for Tuesday night’s show were already aggravated because it took them away from focusing on their own segments for SmackDown.

The Miz didn’t complain at all. Instead, he saw it as an opportunity and spent time with me to find ways we could make our partnership stand out. He genuinely wanted what we did to be good. The more I saw how hard he worked, the more I respected him. I also learned a lot from him on how to navigate the political waters in WWE. He’s also somewhat of a perfectionist; if he wasn’t content with what we were doing, he would talk to as many people as he could to get it changed. Sometimes he was successful, sometimes he wasn’t. But watching him handle it all was really helpful in familiarizing myself with the world of WWE.

Although he didn’t have as much wrestling experience as I did, I recognized all that he had been through. He was mildly famous for being on MTV’s The Real World, which helped him get signed with WWE, but hurt his reputation among fans and wrestlers alike. When he first started, Miz went through a period where he was almost exclusively relegated to hosting various WWE segments like the Diva Search. Backstage, he was kicked out of the locker room because, supposedly, he accidentally spilled crumbs over someone’s bags and didn’t clean it up. His gear was literally thrown out into the hallway, and he wasn’t allowed to change in the locker room for months. Despite all this, he didn’t quit or give up. Even though there was a portion of the locker room that still felt he didn’t belong, Miz’s hard work and ability to get under the crowd’s skin was making the right people take notice, and by 2010, he was really on the rise.

As I mentioned earlier, the inaugural episode of NXT went really well—so well, in fact, that I thought for sure I was a ringer for the show, a natural favorite. It turns out that wasn’t the case at all. On the second episode, they had me heavily tape my ribs from the match with Chris Jericho the previous week, in which I did a suicide dive onto Jericho and hit my ribs hard on the announce table, instantly bruising me up. WWE.com covered it, and the moment was replayed during my entrance, so it was fresh in fans’ minds. That night in week two, I wrestled Jericho’s Rookie on the show, Wade Barrett, who beat me in three minutes. There was an embarrassing moment when I slipped trying to do a springboard into the ring, but Wade covered it perfectly by immediately hitting me with his finish and pinning me. At the announce booth, Jericho helped out the situation as well, because he was on commentary and claimed that I slipped because of my damaged ribs, then took all the credit for Wade’s victory.

After the match, without warning, Chris started beating me up and put me in his submission hold, the Walls of Jericho, essentially a modified Boston crab. I didn’t know it was coming, and it wasn’t preplanned; Chris was on commentary, and Vince directed him over the headset to do it. For most of the season, we Rookies had no idea what was going to happen on each show, but there were times when the Pros didn’t know either.

The next few shows fell in line with the story I expected. Miz and I teamed together, and he ended up getting pinned because he and I were arguing. The following week, Miz wasn’t there, so he scheduled me in a match against the Great Khali, a seven-foot-one, 350-pound Indian giant, which was my punishment for causing him to lose. I lost the match, but as long as I put up a good fight and showed heart, it didn’t matter. It was all about the story between Miz and me.

Also around this time, I realized that moving to Florida was a complete waste of time. FCW was only able to book me on a handful of shows because of the number of people with developmental contracts who needed the experience. The matches I did have were mostly multiperson tag matches with the other seven NXT Rookies, so I’d only be able to get in the ring for a couple of minutes. The last match I did for FCW was the straw that broke the camel’s back. We were doing a four-on-four tag match, and due to some sort of confusion or mishap, I didn’t even get tagged into the match. After that, I spoke with Dr. Tom and decided I needed to move back to Las Vegas, where I’d be able to at least stay in shape with my grappling and kickboxing and keep my kicks sharp. Instead of driving myself across country, I paid my friend Kristof to drive my car back—and, like what happened on my drive to Florida, my car ended up breaking down on him as well. Fortunately, Kristof got it fixed and into Vegas just in time for me to move into my new apartment—perfect timing, actually, because NXT was being taped in my city that following Tuesday.

A week after my loss to Khali, things took a turn for the worse. We were in San Jose, California, for Miz’s second week in a row of not being on the show, and they had me teaming with Michael Tarver against Darren Young and David Otunga. I learned of the match from producer Mike Rotunda, who told me I was scheduled to lose in order “to keep up the losing streak gimmick.” I was a little taken aback. I’d lost every match on NXT so far, but there were reasons for each loss that advanced the story with Miz and me. With him not there, they just decided to turn the story into a losing streak. WWE had tried this several times with other wrestlers previously, and it never really worked; they would usually just forget about it, and the fans would just start seeing the guy as a loser. I started getting a little worried.

The next day, I had my first (and, really, my only) experience of disrespect by another Superstar, while headed from San Jose to Phoenix for my first-ever WrestleMania with WWE. All of us who performed on the SmackDown and NXT tapings were on the same flight, including the NXT Rookies. The eight of us were sitting in booths near a food court at the airport, along with Regal. Ezekiel Jackson, a muscular, 300-pound guy who had only been wrestling for a couple of years, came up to us and said, “Which one of you rookies has an aisle seat?” He had a middle seat and wasn’t happy about it.

“I do,” I said.

“Not anymore you don’t,” he responded.

I could see what was going on, but still replied, “What do you mean?”

“I’m taking it,” he said.

The previous night (the “losing streak” thing) already had me frustrated, and I didn’t feel like taking any shit.

“No, actually, you’re not,” I said. “And actually, had you asked nicely, I would have gladly given you my seat. But since you didn’t, I’ll just give it to somebody else.”

Jackson was infuriated, but just as he was about to respond, Regal chastised him. “Do you even know who you’re talking to?” he said. “This man is like a son to me and has more talent in his little finger than you have in your entire body.” With that, Jackson left, and I gave my aisle seat to someone else and took his middle seat.

After that, my WrestleMania week was a blast. We had a handful of appearances, though not many. I had one signing where I replaced Evan Bourne, who was pretty popular at the time. He had a line of substantial size when I replaced him, and when the announcement was made about it, the crowd’s disappointment was audible as half of the line left.

I ventured around the city using public transportation, trying to find the best vegan food. Ring of Honor was doing their yearly shows in the vicinity of WrestleMania, so I went to one of them, hitching a ride with some fans who were going as well (including one who is a radio DJ in Philadelphia and interviews me regularly today to promote upcoming shows). On Sunday of that weekend, we actually got to participate in WrestleMania XXVI—not in any big way, but we still got to go out there. On the pay-per-view preshow, there was a big battle royal, and since we were considered Rookies, they sent us out to the stage to watch “so we could learn.” The winner of the battle royal was Yoshi Tatsu, a Japanese wrestler I competed against once in New Japan when he was a young boy. I guided him through that match, and it mildly amused me that I was now out there pretending to learn from him.

On that show I actually did learn from, and was emotionally touched by, Shawn Michaels’s retirement match against the Undertaker. It was by far the best match on the show. Not only that, with a crowd of seventy-two thousand people and the atmosphere being simply electric, it might be the most memorable match I’ve ever seen live. I watched it from the stands so I could take in the entirety of it. Shawn Michaels trained me, and there I was, my first WrestleMania and his last.

For the NXT after WrestleMania, they advertised the first results of the Pros Poll, a legitimate vote by the WWE Pros ranking each of our abilities to be WWE Superstars. Since they just had the Pros write down their genuine thoughts on our standings, I ended up being ranked number one, despite not having won a single match. I can imagine the fans were very confused, given the idea that winning and losing is supposed to matter. The Pros Poll was important because you were eliminated from the show if you came in last. The first one, however, was just a demonstration; no one would be eliminated until week twelve of the competition, we were told. Still, I felt confident that no matter how many matches I lost, as long as the voting was legitimate, I would do fairly well on the show.

The following week, WWE changed plans entirely on what NXT would be, and they essentially turned it into a joke. Instead of making it a vehicle for us to exhibit our skills as wrestlers, they decide to fill the show with silly challenges that have nothing to do with wrestling; we carried kegs, ran obstacle courses, and jousted like the American Gladiators in a contest called “Rock ’Em, Sock ’Em Rookies.” In the middle of one challenge, we had to run upstairs and drink a big cup of soda as fast as we could. (Originally it was supposed to be us eating a hot dog, but since I was vegan and they couldn’t find any veggie dogs, it was switched.) Since I don’t usually drink carbonated beverages, it took me almost sixty seconds to complete that task alone. That’s right, on a show that was regularly viewed by one million people, NXT viewers were subject to a full minute of watching someone try to drink a soda. Now, that is quality television.

The only reason to care was that if you won the challenges, you got points, and by the time we did the first elimination, whoever had the most points was immune to being ejected. But the challenges were so inane and demoralizing that by the end, we all treated them as a joke—except, that is, for Skip Sheffield (later known as The Ryback), who demonstrated an undeniable will to win even the most idiotic game.

On top of the challenges, the commentators consistently kept putting us down, especially Michael Cole. Any little mistake in the ring or on the microphone would be called out instantly, and the audience would be reminded of how we were “just rookies.” I was persistently ragged on for being a “nerd,” ostensibly because I had wrestled on the independents so long and had a decent-sized following on the Internet. Instead of us doing things to make us more popular, we were treated like fools. It’s hard for me to imagine the Undertaker ever becoming the legend he is today if, when you first saw him, he was falling off greased monkey bars while the announcers told you he was stupid for trying to be a dead man. Then again, it’s possible WWE never saw the potential in any of us to be that kind of star.

Not only were we presented in ways that made us look like schmucks, we were also segregated from the rest of the locker room. Despite all eight of us being under contract with WWE, we had to change in a separate dressing room, which usually wasn’t a dressing room at all. They would put up pipes and drapes to cover up a little hallway, with no bathroom or shower. One time, our designated changing area was amid the lunch tables set up for the local crew guys to eat at during breaks. We had to hold up towels over ourselves while we changed so people eating their food didn’t have to see our dicks.

Even though my character ended up being a nerd who lost every match (I finished NXT a resounding 0-10), I tried to stay positive. This one week midway through the season, after he came out of a TV production meeting, Arn Anderson told me the only way I’d ever get a real opportunity was if the fans got behind me. He told me he believed in me and assured me that the fans can tell when someone is the real deal.

One week prior to the first elimination, in another unscripted interview, Matt Striker asked each of us at the end of the show who we thought should be eliminated. Most guys pinpointed Michael Tarver because of his bad attitude, but since I’d lost to him earlier in the night, it didn’t make sense storywise for me to say him. Since I had lost to everyone else on the show, it didn’t make sense for me to say any of the others either. So, thinking it was the right, humble good-guy thing to do, having not won a match, I said I should be eliminated. Afterward, Miz told me I shouldn’t have even put that perception in the fans’ minds. I was facing an uphill battle as it was. To me, it seemed logical; plus, I figured there was no way I’d place last in the Pros Poll and get eliminated.

When it was time for the first elimination the following Tuesday, we were told to line up by the ring before the show started, again without being told what was going on. Striker came out and reminded the fans that the previous week he asked us who should be eliminated. Michael Tarver had said himself as well, with his justification being everyone was safer without him around. Striker then said, “WWE management feels that if a Superstar does not believe in himself, then how can anyone believe in the WWE Superstar?” And with that, he told Michael Tarver he had been eliminated by management.

After Tarver exited, Striker walked slowly down the line toward me. They replayed the video of me saying I should be eliminated, and I knew what was coming: Striker announced that I was eliminated as well. As I slowly walked up the ramp to exit, a million things were going through my mind, but the one that kept sticking in my brain was that WWE did this to prove a point. All the things I’d heard from guys like Colt Cabana about WWE’s negative feelings toward independent wrestlers seemed to be confirmed. Given that I’d been the flag bearer for independent wrestling over those last few years, it all of a sudden made sense why they would mock me on the show, despite me being one of the best performers. Then I thought they might just fire me after this and I’d go back to the independents as a failure. When I walked through the “Gorilla position” (the space immediately on the other side of the curtain, named after Gorilla Monsoon), I was informed I’d have an interview with Striker after the commercial break and that I should just answer however I felt was right.

The interview started off fine with a fairly harmless question from Striker about whether I thought the whole thing was fair. I knew Matt was fed his questions by producers and probably Vince himself, but the second question was insulting. He asked, “Do you regret leaving the independent scene, where you were a big fish in a small pond, to ultimately drown in the sea that is the WWE?”

Fuck you. In no way, shape, or form did I “drown” in WWE. I was booked as a loser and was still the most popular guy on the show. This only confirmed to me what I thought coming up the ramp. But I answered relatively calmly.

“Well, that’s funny, because ‘Daniel Bryan’ never wrestled on the independent scene,” I said. “If you go on and YouTube ‘Daniel Bryan,’ all you ever see is WWE. But there was this guy, man, he was out there, he was kicking people’s heads in; people called him the best wrestler in the world. He was a champion in Japan, Mexico, and Europe. And do you know what his name was?”

Before I could say it, Striker cut me off, saying, “What’s next, for this guy?” I could practically hear the yelling in his earpiece, but I continued on. I downplayed the skill of “Daniel Bryan,” saying that guy couldn’t even beat rookies. And then I said it.

“‘Daniel Bryan’ might be done, but Bryan Danielson—God knows what’s going to happen to him.”

When I said my real name, it actually got a reaction from the fans. It got a reaction from Vince as well; apparently, he threw his headset. I was in the frame of mind that if I was going to get fired, I was at least going to plug my own name before heading back to the independents. But because NXT wasn’t quite live (it was on an hour delay), they made me redo the interview, and Striker asked different questions. When the show aired, however, they played the original on TV. Vince must have changed his mind in the meantime.

It seems to me that Vince’s perception of me is always changing. It’s actually strange to think about what somebody else is thinking about me. I’ve never really worried about it, but when one man can change the whole dynamic of your career, you tend to wonder. When I first started on NXT, I got the distinct impression that Vince didn’t like me. After the first episode, Jericho came back and told Vince he thought I was great in the ring, but otherwise, Vince’s reaction to me was “Ugh, but he doesn’t even eat meat!”

Then I thought he just liked to pick on me. Shortly after NXT started, all eight NXT Rookies joined about six other Superstars each week before TV for what they called “promo class,” which was led by Vince himself. Vince would call people up to the front and have them cut promos on random subjects. You had ten seconds to think, and then you just had to go. Afterward, he’d ask other people in the room what they thought of your promo, and then he’d give you his own opinion. He was very hands-on.

From our very first class, it seemed like he singled me out. He had me cut a promo on a table, and it was rotten. I got nervous because I’d never done anything like that before and it was in front of many people I respected, like Rey Mysterio and Fit Finlay. Every promo class, he called me up—sometimes more than once—but with each class, I grew more confident and I got better. One promo class, he decided to make us the teachers. First, he had Big Show go up and teach, then Matt Hardy. Between the two of them, they pretty much said everything that Vince had taught us, and they called up different people in the class to do promos as well. Neither of them called me up, so when Matt was done, Vince stood up and told me to go teach the class. It was a horrible position to be in. At least Matt and Show were veterans in WWE. Nobody wanted to be taught by a guy on NXT who wasn’t even known as giving a good promo. Regardless, I went up and tried to keep it short, not repeating anything Show or Matt had said. I pretty much just told everyone how important I thought it was to be yourself, then work from there to identify your strengths and weaknesses. When it was time to call somebody up to cut a promo, I named Vince. His topic: “How great Daniel Bryan is.”

Vince stood there in front of the class, silent. Then he looked me up and down, judgingly, before his face turned to various levels of disgust, amping it up as he went along. Vince never said a word for about a full minute, and then he said he was done. He went to sit back down, and I stopped him, requesting he stand up front while the class critiqued his promo. I first called on Big Show, who put it over the moon. The next person did the same. And they were right. It was great, and the whole room was laughing. I excused Vince to go sit down, but then he said there was a lesson there. He taught us about the importance of facial expressions and how to say something without saying anything. It was really good.

The last time Vince called me up front in promo class was one that included everybody on the roster. When I was called upon, I accidentally knocked over my bottle of water, spilling it all over the floor. I was embarrassed, but then he started asking people how that incident made them feel about me. (Most said it made them feel sympathetic toward me.) Next, he asked me a series of questions—definitely not the usual class protocol of having me cut a promo on something random. Vince made a statement, then said nothing. I asked if there was a question there, and he said there wasn’t, so I just stood there in the front of the room, with neither of us saying anything. I thought he was trying to embarrass me, but then he asked, “What are you doing right now?”

“Nothing,” I said.

“Close,” Vince said, then asked me again, “What are you doing right now?”

I was clueless. “Close to nothing?” Miz let out a groan in sympathy, as if he’d been rooting for me to respond with the right answer and I completely blew it. Vince chuckled.

“No,” he said. “You’re using the silence.” And with that, he excused me to sit down.

On my way out the door, Vince pulled me aside and said, “You know I’m doing this for a reason, right?” I lied and told him I did, but, more importantly, that was the first time I thought he saw more in me than I knew. Even today, he will occasionally bring up how much better my promos got after that experience. And they truly did.

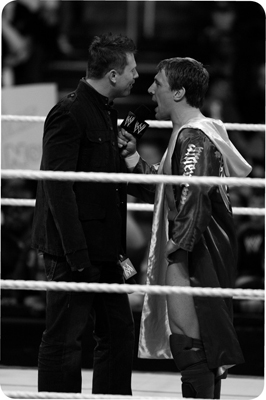

After I was eliminated from NXT, WWE told me they would call me when they needed me, which they guessed wouldn’t be until the season finale. Plans change rapidly in WWE, though, and they called me back to be on the show the very next week to initiate a story with Michael Cole, stemming from all the times he put me down on commentary. It was the first time on NXT that I was able to prepare for promos—using the instruction I learned in promo class—and it was by far the best talking I’d ever done. We went back and forth verbally, and ultimately physically, as I ended up tackling Cole into the barricade as he ran away. We combined this with a continued rivalry with Miz, and it turned into good television. WWE liked it so much that they ended up using our story to turn Cole into a heel on Raw as well.

The final episode of NXT ended with Wade Barrett winning the season and, as part of the story, earning a spot on the main roster. Even though I didn’t win, I was confident that WWE would continue to feature me, given how well the stuff went with Cole and all. As I sat with the eliminated Rookies in the front row, watching the final episode, I was thrilled NXT was over, and I looked forward to moving on to the next step, whatever that would be.