THURSDAY, APRIL 3, 2014—10:58 A.M.

“Braniel” exits their hotel room and splits at the elevator; Brie greets some WWE fans en route to the salon, and Daniel arrives at his appointment for Active Release Techniques (ART) therapy in a quiet hotel suite turned therapeutic studio.

ÖKO water filtration bottle still in tow, Bryan consults with the practitioner, describing tenderness and various effects of the highly physical lifestyle of a professional athlete. He lies flat on the table—belly up first, then on his back—and the specialist uses hard pressure to break up scar tissue in overused muscles.

Bryan’s neck and limbs are swayed back and forth; he’s then locked up in what resembles a half nelson. And repeat. By session’s end, any initial discomfort yields loosening of the muscles. He’s primed for the next phase of today’s wellness: a workout.

Lance, Brian, Shooter Schultz, and I moved to Memphis in mid-June 2000, almost one year to the exact day that I left Aberdeen for San Antonio. Moving to Memphis was a little nerve-wracking for all of us, mostly because we had never been outside Shawn’s protective womb, as far as wrestling was concerned. Shawn was always very protective of us, and he treated us like his kids. There were a lot of things we didn’t know how to do that Shawn made sure we had help with, like getting our apartments or having his wife, Rebecca, take Lance and me to the passport office before we went to Japan. In Memphis we were forced out from under Shawn’s wing and had to learn to do everything on our own. It was probably about time. Brian, Shooter, and I got a three-bedroom town house together, and shortly after moving in, we went to Raw in Nashville and SmackDown in Memphis to show our faces.

We drove with Terry Golden, the promoter and owner of Memphis Championship Wrestling (MCW), which was the name of the developmental promotion. Terry was really nice to us, but it was a far cry from going to the shows with Shawn. The Raw in Nashville was the first time I met William Regal.

Regal was an intimidating figure, particularly to someone like me who’d been wrestling less than a year. He’s tall with a strong jawline, and he had a reputation for being a shooter, meaning he legitimately knew how to hurt you. He had started wrestling at age fifteen, doing shows at carnivals where he’d sometimes have to take on members of the audience. Regal came up the hard way and wrestled all over the world before coming to the United States to compete in WCW in 1993. What makes him even more intimidating is how he speaks very softly, sometimes so softly that you strain to hear him, and that he has the confidence of a man who knows what he’s capable of.

Regal was in WWE’s developmental system to prove he had kicked his pill dependency, which he is very frank and honest about in his book, Walking a Golden Mile. I have only known Regal since he’s been sober, so it’s hard for me to imagine him as the wreck he was prior to getting clean. Before I met him, I had heard the stories—how he pissed on a flight attendant and “shot on” (that is, used legitimate moves or holds on) Bill Goldberg in a live TV match, which wasn’t true. Being at MCW was Regal’s opportunity to prove he could stay sober, and if he did, WWE would bring him back to TV. Not only did he stay sober, but Regal also ended up being the most influential person in my career.

The William Regal I met was nothing like the man I’d heard stories about. He was soft-spoken and funny, and he had a genuine interest in helping anyone who wanted to be helped. Regal took to Brian and me right away when he saw how eager we were to learn. He introduced us to the European style of wrestling, which was heavily based on submissions holds, counters, and advanced mat-based wrestling—something I had never seen before, particularly as it became increasingly more difficult to find European wrestling video-tapes would work in a U.S. VCR.

At first the multiple trainers we had in Memphis—including Jim Neidhart and others—were guys under contract with WWE, helping out until they were either brought back to the main roster or let go. At one point, Regal brought in an English wrestler named Robbie Brookside, who’d helped train Regal himself, with the goal of finding Robbie a role as coach in Memphis. That was the first time I’d met Robbie, and, like Regal, he also became a very influential wrestler in my career.

Since I was trying to switch to a less risky style, Regal was the perfect teacher for me. He would go into detail explaining the finer points of basic holds, and why certain counters make sense and others don’t, given the intuitive visual intelligence people have about the human body. He opened up a whole new world of wrestlers like Johnny Saint and Mark “Rollerball” Rocco, who were great wrestlers, and the way Regal thought and talked about wrestling transformed the way I thought and talked about it. It made sense to me. However, as eager as Brian and I were to learn the European style, a lot of the other guys were not so keen on it. In the fast-paced, live-TV style of WWE, some saw the mat wrestling and counters as slow and relatively boring. They weren’t interested in the specifics of wristlock counters, nor were they receptive to Regal’s broader ideas that wrestling should make sense.

There were exceptions, of course, like this one guy named Reckless Youth, who was one of the more notable independent wrestlers before he was signed by WWE. I heard of him through Pro Wrestling Illustrated, where he would get publicity because he was known for having great matches all over the country. Like a sponge, he soaked up what Regal taught, and since he had years of experience on the independents, he was great at integrating it into his matches. The first several months I was in Memphis I ended up wrestling Reckless a lot, which was a great learning experience because I got to try out all the things Regal was teaching us with someone who had a better concept of what wrestling should be than I did. After every match, I would ask Regal what he thought, and he would point out things I did well and things I could have done better. Brian and I had also taken to trying to record our matches, which helped as well.

Unfortunately for us, Regal got called back up to WWE television not long after we arrived in Memphis. He had been there a year and had not only stayed sober but was performing on a whole other level. Regal had a match with Chris Benoit at that year’s Brian Pillman memorial show that blew my mind. It was a perfect example of how aggressive mat wrestling could work in the modern wrestling environment. After I saw it, I thought, Holy shit! That’s the kind of wrestling I need to be doing. Even though we were only in Memphis a couple of months together, Regal became my mentor, and he has remained my mentor ever since. He’s the person I go to for advice to this day.

We had a lot of wrestlers—a hodgepodge of people—coming in and out of Memphis while we were there. We had guys like Mabel and the Headbangers, who had already been on TV. We had the Mean Street Posse, who were on TV at the time as stooges for Shane McMahon and were being taught how to wrestle (with the exception of Joey Abs, who already knew how but was down in Memphis anyway). We also had the developmental prospects trying to get their first shot at being on TV, which was the biggest group of us—Joey Matthews, Christian York, Charlie and Russ Haas, Rosey and Jamal (who ended up being Umaga), R-Truth (before he became K-Kwik), and countless others during the year I was there. Another talent down there was Molly Holly, who inadvertently brought a big change to the entire group and procedure in Memphis.

Before the four of us (me, Lance, Shooter, and Brian), I’m not sure who was responsible for setting up the ring, but shortly after we showed up, it became our job, presumably because we were so new to the business and needed to pay our dues. We usually had at least three shows per week, so on those days, we’d get to the building early to assemble the ring and then stay late to tear it down. That continued until Nora Greenwald, who went on to become Molly Holly, came down to Memphis. She had just come from WCW and wasn’t going to be in Memphis very long, so she had no reason to be worried about who was handling the ring construction, but when she saw that we were doing it and nobody else was, she offered to help at the end of shows. Shortly thereafter, someone from the WWE talent relations office was at the show, and when he saw Nora helping build the ring, he instantly asked why she was doing it. Terry explained that it was just supposed to be the four of us doing it and Nora had just volunteered. When word got back to the office, they started making everybody—main roster refugees and new faces alike—work on the ring. Needless to say, people weren’t happy, especially since MCW was a relatively demoralizing organization in the first place.

One of the reasons Shawn Michaels had put a mask on me back in TWA was that I was not very expressive—a recurring criticism throughout my independent days. Eventually, Shawn and Rudy thought I’d started to develop facial expressions, so they took the mask off me and changed my character. As soon as I got to MCW, they told me they wanted me in the mask again.

The MCW shows we ran usually had very small crowds. We did a Wednesday night show every week in Oxford, Mississippi, at a bar where people didn’t even have to pay to see us. The forty-five people who were usually in attendance were there mostly to drink, and in between swallows, they’d watch the show and heckle us.

MCW taped television shows as well. Initially we filmed at a really cool spot on Beale Street, but that didn’t last very long. Soon we were filming anywhere they would let us, like at armories and half-empty high school gyms. By the end of MCW, we were doing shows at gas stations and random locations like that. My favorite place we did television was in a Walmart parking lot, where shopping carts doubled as a guardrail and we all made our entrance out of the RV we all dressed in. This created a semicomical scenario where bad guys were running out of the RV to attack a good guy, more good guys came out of the same RV to chase the bad guys back to the RV, and then the good guys walked back to the same RV moments later.

Another real demoralizer for most of the guys was that very few people were being brought up to the main roster from Memphis. It didn’t bother me too much because I’d never really gotten my hopes up that I would be brought up anytime soon. The only time my getting called up to TV was alluded to by WWE was around Royal Rumble 2001, when we were told WWE was looking to start a new cruiserweight division like the one that was popular in WCW. Brian and I were told they wanted to use us for it. Of course, that never happened.

There were certainly good moments as well. In February 2001, WWE renewed all four of our contracts for another year, and I was able to save some money. I earned enough to buy a 2000 Ford Focus and replace my old car, which was breaking down. I didn’t have enough to pay for it in cash, so I had to make payments, which turned out to be a big mistake given what would happen a few months later in June. I also bought my first bed after more than a year and a half of sleeping on floors and inflatable mattresses. When I got a bed and a car, I felt like I was living a life of luxury.

The positive moments continued when WWE sent Regal down for a big show and I was able to wrestle him for the very first time. We were reaching the end of having a really fun match, which he was supposed to win. I went to the top rope, jumped off, and gave him a flying dropkick. As I covered him, he told the ref to count three and he didn’t kick out. In a completely unselfish act, he let me win. By that point, I had learned a lot from him already, but there is no better way to learn from someone than being in the ring with him. I learned a ton in that match. And not just about wrestling.

In June 2001, shortly after WWE had bought WCW, we went to the training center for what we thought was another normal day. When we walked in we could tell something was up. Terry introduced a guy I didn’t know from WWE’s talent relations department, and they let us know they were closing down the development territory in Memphis. We were told some of us would be sent to the other developmental territories in Cincinnati or Louisville but, unfortunately, some of us would be fired. They were going to let us know our fate one by one as they called us into the office. I went in third; of the two guys who went before me, one was fired and one was sent to Cincinnati. When I walked in, I knew the score. The man said that although they thought I was very talented, they didn’t have any current plans for me and they were going to let me go. Some of the guys who ended up getting fired got angry and threw stuff all over. I was just devastated, left with no idea what to do next.

Under our contracts, if you were fired, you’d still be paid for ninety days. But in order for us to get our money, we had to stay in Memphis and continue working the remainder of the MCW shows. Morale was understandably low, and these shows were the worst I had ever been a part of. Even the guys who were kept on and being sent somewhere else couldn’t be excited or in a good mood, because half of the locker room had been fired. There was a lot of backstage drinking (and probably some other stuff I wasn’t aware of), and ultimately Memphis went out with a whimper. The last show we had scheduled was in a parking lot of a pawnshop. We were getting changed in the store’s restroom when all of a sudden it started raining. Terry decided to just cancel the show. We all went out, loaded up the ring in the rain, and took a group picture in front of the trailer. So ended Memphis Championship Wrestling.

Although I was very, very depressed after getting fired, I was also very fortunate for the opportunities I received while under contract. Former WWE Superstar Charlie Haas and his brother Russ were really close with Jim Kettner, a top independent promoter out of Delaware who ran the East Coast Wrestling Assocation (ECWA). In 1997, Jim created an increasingly popular annual tournament he called the Super 8, featuring the eight best independent wrestlers from around the country. When the Haas brothers came down to Memphis and saw Brian and me wrestle, they told Jim they thought we’d be great for the Super 8. Charlie suggested that I would be the perfect opponent for Low Ki, who was tearing up the northeast indie wrestling scene and was Kettner’s top prospect. When he called and asked me to participate, I gladly accepted. Kettner often worked with WWE to promote live events in Delaware and had a good relationship with the organization. He promised WWE (and me as well) that he would put me in matches where I would have the chance to shine. And, boy, did he.

In the first round, I wrestled Brian; in the second round, I wrestled Reckless Youth (who was gone from WWE by this point); and in the finals, it came down to me against Low Ki. All three of my matches went really well, and the Low Ki match, specifically, got a great reaction, not just because it was the finals but because we were blending hardnosed mat wrestling with stiff kicks and chops in a way that American independent fans weren’t used to. The Super 8 received a great deal of coverage, including in national magazines like Pro Wrestling Illustrated, so I got a lot of good publicity out of it. Honestly, if I had not competed in the tournament, I would’ve had a difficult time securing bookings once I was fired, since before the Super 8 nobody really knew me outside of San Antonio and Memphis.

After I got fired from WWE’s developmental system, I moved back to Washington—pretty much what I’ve done nearly every time I don’t know what to do. I went back to living with my mom and tried to come up with a new game plan. There wasn’t much wrestling in Washington, but I had contacted a company in Vancouver called Extremely Canadian Championship Wrestling (ECCW). They were interested in using me, which was great because almost every weekend, they ran three shows. Jim Kettner still brought me in for his ECWA shows on occasion as well, and I thought that between these opportunities, plus continued word of mouth around the American Dragon, I could essentially avoid getting a “real” job and live off my savings.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t. Though I initially planned to have my new car paid off by the end of the year, getting fired made it hard to manage monthly payments and other bills. At ECCW, I was only making $75 Canadian per show (about $45 U.S.), minus the cost of gas for my twelve-hour round-trip drive.

Whenever I worked for Kettner, I made $100, but that was—at most—once a month, and I wasn’t getting many other bookings elsewhere. So I ended up getting two jobs, one at an after-school program for elementary school kids and another at a combination video store/tanning salon called Video Tonight, Tan Today. Even with an already fairly crowded schedule, I started taking classes at the local community college, too.

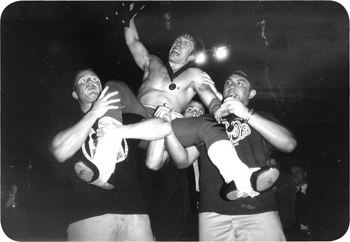

Bryan wins the 2001 “King of the Indies” tournament

(Photo by Dr. Mike Lano)

I got a big break in October 2001, thanks to Roland Alexander, a promoter out of California who ran All Pro Wrestling (APW). The prior year, he’d organized a tournament called King of the Indies. Based out of the Bay Area himself, Roland used almost exclusively West Coast wrestlers in his first eight-man tournament. The following year he decided to do something a little different by making it a two-night, sixteen-man tournament and bringing in wrestlers from all over the country, as well as Doug Williams from England. Based on our performances in the Super 8, Roland offered Brian and me a spot each in his elite tournament.

On the first day, Roland matched me up with Brian for the opening round. Since we’d wrestled each other over a hundred times by then, we had a really good match that caught the attention of one ring legend in particular. Nick Bockwinkel, who was among several other legendary wrestlers presiding over the show, approached Roland at the end of the first night. “If you don’t put that guy over,” Bockwinkel said, pointing directly at me as he suggested I win, “you’re crazy.” Though it certainly was not the original plan, Roland took his advice—a decision that created a lot of drama and controversy the following day.

Initially, Donovan Morgan, who was the head trainer at the All Pro Wrestling school (the promotion’s true moneymaker), was scheduled to beat me in the semifinals and then go on to win the tournament. He was red-hot about the switch, but that wasn’t the only thing he was angry about.

On the morning of the second day of the tournament, Roland—immensely impressed with our performance the previous night—offered me and Brian roles as trainers at the APW school. He explained that he needed a new head trainer because Donovan was spending a great deal of time wrestling in Japan. Even though the two of us were relatively inexperienced, Roland said, he believed we would be great trainers. We told him we’d think about it, then went and asked Donovan how the job was—not knowing, of course, that Roland hadn’t told him about the proposition. Donovan was furious, though at Roland, not at us.

That night, I wrestled Doug Williams, which was fun because he knew how to do all the European-style wrestling that Regal had taught me. The momentum shifted later on in the semifinals, where I wrestled Donovan. Feeling betrayed and discouraged, he didn’t really get into our match or want to do much of anything to make it a memorable performance, which was understandable. It was a short, lackluster match, unlike my final-round encounter with Low Ki, which was essentially a rematch from the Super 8 finals. We wrestled for nearly thirty minutes, incorporating the same elements that made our previous match unique. I won with a submission move I’d started using at the Super 8 as my finish: the Cattle Mutilation, a bridging double chicken wing with my opponent on his stomach. This move became my calling card for the rest of my time on the independents.

Recognizing that a former vegan’s use of something called Cattle Mutilation may be a bit unexpected, I figure the origin of the move’s name might need some explanation. I first saw the hold at a National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) show called Future Shock ’89, a round robin tournament among the top NWA stars of that time, including the Great Muta, who was one of the most exciting wrestlers of that period. All of a sudden, in the middle of a match, Muta pulled out this bridging double chicken wing. It got no reaction and was barely mentioned by the commentators, but I thought it was awesome. I started using it when I was in Memphis, though only a few times as a finish. When I did use it, I called it a “bridging double chicken wing thing.” The first time I heard the words “Cattle Mutilation” was when I wrestled Reckless Youth in the Super 8. I told him I’d like to beat him with a full nelson suplex, but given I’d just beaten Brian Kendrick with that submission in the previous round, he told me he thought I should also beat him with Cattle Mutilation. I had no idea what he was talking about. “Cattle Mutilation,” he said, “that’s what that submission is called.” He looked at me like I was a dummy and walked off. I took his advice for the finish, but thought the name was wacky and assumed I’d never hear it again. Shortly thereafter, however, when I wrestled Christopher Daniels, he called it Cattle Mutilation as well. By the time Ring of Honor (ROH) started, everyone called it that. Everyone, that is, except me. I had no idea where the name had come from and hated the imagery, so I stubbornly continued to call it my bridging double chicken wing thing. It wasn’t until late 2002 that I finally accepted that the move would always be known as Cattle Mutilation, despite my greatest efforts. Such is life.

Immediately following my victory in the King of the Indies tournament, I was presented with this huge trophy, which I actually got to keep (unlike other wrestling trophies, which are usually just for show and taken back shortly after they’re given to you). But more important than the trophy was that this positioned me as a main-event wrestler on the independents. That two-day APW tournament on October 26 and 27 was the inspiration for Ring of Honor, and my win made people see me as a top guy right away, including the people responsible for ROH when it came to be.

After the tournament, Brian and I weren’t sure what to do about the APW trainer roles. If nothing else, we were both broke and could use the money. Despite the opportunity, Brian decided not to take it. Before I could decide, I made an important phone call to Donovan to ask if it would be OK with him if I did take the job. He said he was fine with it and encouraged me to do it because it would be a good experience for me. Whether he meant that or not, I have no idea, but the next day, I called Roland to tell him I was interested. I would be earning $350 a week and given a place to stay. Plus, my weekends would be free to take independent bookings. I was sold. I gave notice to my jobs—both the school and Video Tonight, Tan Today—then finished up the quarter at the community college. On January 1, 2002, I moved to Fremont, California, to become the head trainer of a wrestling school.

When I moved down to train at APW, I really had no idea what to expect. Roland gave me the address for where I’d be living, and when I arrived, the house I pulled up to was nice and in a great neighborhood. What I didn’t realize was that I would be living with Roland himself, as well as another promoter named Doug Anderson, who was the father of one of the girls in the training program, Cheerleader Melissa. Also in the house was Roland’s eighty-eight-year-old uncle Al. We were quite the household. I had a small room on the second floor of the house and, sure enough, I was back to sleeping on the floor.

For a while, the APW wrestling school was immensely profitable—by independent standards, that is. Roland and All Pro Wrestling received tremendous exposure after being heavily featured in the wrestling documentary Beyond the Mat, in which two APW trainees received WWE tryouts. After the film came out and garnered some success, Roland was able to charge much higher rates. Whereas I paid $3,900 to train with Shawn Michaels, Roland was able to charge $6,000 per student. Not only that, but he signed new trainees to contracts that required them to pay their complete balance even if they quit.

Each class was limited to twenty students, and before I got there, almost all the classes were full. Their strategy seemed to me to be to work the students to death the first several weeks so that only those who really wanted it would stay. The quitters would forfeit some of their tuition, which didn’t seem right to me.

By the time I moved to Fremont, Donovan Morgan and Mike Modest, another one of Roland’s former trainers, had opened up a school and promotion called Pro Wrestling Iron in the same area to compete with APW. The rival organization would bash Roland’s APW on Internet message boards, which led those in APW to do the same about Pro Wrestling Iron.

The increased competition created a sharp decline in students for All Pro Wrestling, though that wasn’t the only contributing factor. I wasn’t only in charge of training, but also recruitment. I was responsible for contacting anyone—from nearby and all over the world—who filled out enrollment applications. And Roland didn’t just want me to call them once. He wanted me to call them at least every month for a full year. Donovan had done that, and his ability to call people and sell them on the school was one of the reasons APW was so successful. I, on the other hand, was less good at it.

Roland asked me to spend thirty minutes to an hour each training day calling prospective students. I did it at first, but it just wasn’t in me to try to sell people on becoming a wrestler, especially when I knew the price tag. I’ve always thought that if someone really wanted to wrestle, they’d do it and not need to be sold on anything. That is why I’m a horrible businessman.

To be honest, I wasn’t that much better at training people to wrestle. I was actually quite good at breaking down the movements of wrestling, but I was bad at motivation. I never needed anyone else to motivate me to work hard at wrestling, to watch tapes, or to try new things. All of that was fun for me, so it didn’t ever seem like work. In my classes, I’d start off by showing them something, then opening it up for them to ask what they wanted to learn. That’s how I learned, but I was self-motivated. Each session, I told the trainees to come in with three things they wanted to work on the next day, and very rarely did they come in with anything specific. I ended up being a frustrated trainer because I expected them to be self-motivated like I was. For most of the trainees, it seemed like wrestling was something they just wanted to try, not something they were determined to do. I tried to be very encouraging, but to succeed in wrestling, you need a certain degree of passion, and I had no interest in trying to inspire passion in people.

The only student I taught who really succeeded was Sara Amato, who has traveled all over the world wrestling and today is an accomplished trainer for future Divas down at the WWE Performance Center. Prior to my arrival at APW, Sara had already been training with Donovan, but she injured her knee, so she was essentially starting from scratch when I got there. She worked really hard, she was constantly studying tapes, and in general she was tough. One time, I was teaching back body drops, and the girl she was in the ring with collapsed under her, causing Sara to land on her shoulder and separate it. She let out an expletive, rolled out of the ring, popped her own shoulder back into place, then got back into the ring to do it again. Another reason I was a bad trainer: I let her try to do it again. She took the back body drop a second time, and when she landed, her shoulder popped out again. Once more, she cursed, rolled out, popped it back in, and was ready to get back inside the ring. At that point, I stepped in and told her she was done for the day, and then I instructed her to go see a doctor. Even though Sara wasn’t making the wisest decision to fight through an injury like that, it demonstrated her passion for wrestling. When people ask me what it takes to be a wrestler, I always say passion is the most important thing. Well, passion and luck.

All of that said, I truly enjoyed training people. Teaching forces you to learn your craft better in order to explain it to other people, and at that point in my career, still being so new to wrestling, it helped me a great deal. Plus, I really enjoyed the Bay Area, and despite my doubts about the living situation, it turned out to be fun. Roland, who passed away in 2013, was witty and funny, and he always had something interesting to talk about, mostly wrestling gossip. Doug Anderson was a kind man, who always seemed to be in good spirits.

Living with Roland’s eighty-eight-year-old uncle was what made the situation truly unique. Uncle Al had a hard time hearing and seeing. When I first moved in, he was able to dress himself, but after a month or so, Roland had to start laying out his clothes for him. He went from wearing his usual nice pants and a buttoned-up shirt to clothes Roland wore, which is why one day Uncle Al came out confused with basketball shorts over his dress pants.

On Uncle Al’s eighty-ninth birthday, we decided to throw him a surprise party, complete with an ice cream cake and tons of decorations. As Roland and I went through the party supply store Roland grabbed two candles, one that was an 8 and another that was a 9. I stopped him and pointed out how rare it is that people live to be eighty-nine. Roland agreed with my suggestion to celebrate with eighty-nine candles. It was just a matter of regular candles or “magic” candles, the kind that don’t blow out. Without really thinking things through, we chose the latter.

After training, we invited all the students over to the house for Uncle Al’s big birthday bash. We got everybody party favors, like hats and kazoos, and had even found a bunch of paper Batman masks because we thought they were funny and would confuse Uncle Al. Training ran late, so we all got back to the house around 9 P.M., which was about two hours later than Uncle Al’s usual bedtime. Since he couldn’t hear very well, the noise of us all coming in didn’t wake him up. We quickly set up all the decorations and got to work on the ice cream cake, which we planned on bringing into his bedroom. Not one person—not even Doug, who was a sensible, reasonable adult—brought up that it might be a bad idea to put eighty-nine candles that don’t blow out onto an ice cream cake.

We organized all the candles on the cake, which required us to put them very close together. We were less than halfway through when the candles all caught on fire and created an inferno, so high that it left black marks on the ceiling. Of course, what do we all do? We start trying to blow them out … which didn’t work because they were magic fucking candles. I grabbed the cake and tried running it to the kitchen sink to put the fire out with water, while Roland went to wake up Uncle Al so he could see the mess we created. The kitchen faucet didn’t work, so as I ran outside, I dropped the cake on the floor. By this point, Uncle Al—dressed only in his boxer shorts and a white tank top—was ever-so-slowly coming out of his room, yelling, “What the hell is going on?!” Sara ran to get a knife and a plate. We cut a piece of the salvaged cake and lit one candle on it, and when Uncle Al emerged, we gave him the cake as we all sang “Happy Birthday.” Unexpectedly, Uncle Al started crying. In nearly nine decades, it was the first birthday party he ever had.