William Henry Courtenay, was born around 1788, the eldest known illegitimate son of William, Duke of Clarence, later King William IV by an unknown mother. One source speculates that he might have been born near Lake Courtenay in Nova Scotia, or to be more precise Shelburne, which the Prince had visited in October 1788. By the following year, the latter was back in England and had taken up in quick succession with two young women, Sally Winne, the daughter of a Plymouth merchant, and Polly Finch, ‘a handsome young woman who plied her trade in London’. Not surprisingly the Prince’s reputation suffered a great deal with this type of behaviour, and indeed his army friend Lieutenant William Dyott recorded of him that he ‘would go into any house where he saw a pretty girl, and was perfectly acquainted with every house of a certain description in the town (Shelburne)’. He was known by his friends as ‘Silly Billy’. Other sources have suggested that William was conceived and born in Hanover.

It was not until the Prince met Mrs Jordan and settled down to a decade of cosy domesticity, that his reputation improved somewhat. That the Duke and Mrs Jordan were intimate prior to 1793 it clear from the fact that she miscarried the Duke’s first child by her on 6 August 1792, the Duke declaring ‘the papers have on this occasion told the truth, for she was last week for some hours in danger, but now, thank God, she is much better and I hope in a fair way of recovery’.

Young Courtenay first appears in the Prince’s household in 1794 and was cared for by Mrs Jordan, despite the fact that she was not his mother. Indeed he was very fond of her and she of him: ‘I left William at school’ she wrote on one occasion ‘who cried on my leaving him, and told Mrs Sketchley that he would rather live with Mrs Jordan…’ On another occasion Mrs Jordan wrote to the Prince that he was ‘a very fine boy and will, I am sure, prove himself everything you wish’.

Courtenay’s first taste of the naval life came in 1803 when he joined the ship Majestic at Plymouth as a volunteer 1st class, aged fifteen. The ship’s captain was none other than Lord Amelius Beauclerk, third son of the 5th Duke of St Albans and himself a great-great-grandson of King Charles II. The Majestic was part of the Channel Fleet that blockaded Brest and guarded the approaches to Ireland in order to prevent the French transports from invading England. His next assignment was a stint of service in the Tribune which took him to Gibraltar and on the homeward journey witnessed the capture of five small Spanish vessels. Next the Duke obtained for him the post of midshipman on the ship Blenheim which promptly sailed for the East Indies escorting a convoy of twenty-two East Indiamen. The ship arrived in India on 23 August 1805, and whilst there Courtenay was transferred to the frigate Macassar only to return to the Blenheim a short time after. In retrospect this was to be a fateful decision, because the Blenheim was not seaworthy, having run aground on a sandbank in the Straits of Malacca. On 1 February 1807 the ship was caught up in a squall six hundred miles east of Mauritius and lost with all hands on board, including young Courtenay – a loss keenly felt by his father and Mrs Jordan. Writing a year later to Thomas Coutts, the banker, the Duke speaking of his children, remarked ‘I have lost one who was drowned in the Blenheim. I have one in the Army and at the Military College, the second in the Navy.’

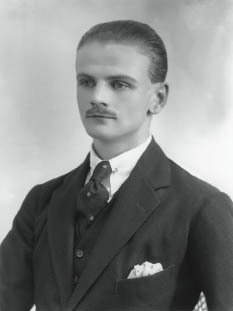

George FitzClarence was born on 29 January 1794 at seven o’clock in the morning in Somerset Street, off Portman Square, London, the eldest of five sons and five daughters all born to the indefatigable Dorothy Bland alias Mrs Jordan (1761–1816), the well known comic actress, by her Royal lover the Duke of Clarence, later King William IV. This liaison was popularly described as ‘his bathing in the River Jordan’. George’s date of birth differs from that given in The Complete Peerage and was taken from a list prepared by William IV and signed by him in the Archives of Wemyss Castle.

Dora, as she was known to William, the younger daughter of Francis Bland, an actor and stage hand, (and himself the third son of Nathaniel Bland, an Irish Judge), possessed many good qualities but chastity was not one of them, having previously had three illegitimate children by Sir Richard Ford, a police magistrate, and another son by Richard Daly, the manager of the Theatre Royal in Cork. Her fecundity was remarkable, and at her death she was survived by no less than thirteen of her fourteen children. Her family’s motto Nec Temere Nec Timide (neither rashly nor fearfully) was not followed by the Duke and his lover, as their twenty year affair was conducted openly and all their children were given the surname of FitzClarence. She was described by Leigh Hunt (RA-GEO/Add/40/255) as ‘so pleasant, so cordial, so natural, so full of spirits, so healthily constituted in mind and body, had such a shapely leg withal, so charming a voice and such a happy and happy-making expression of countenance’

Nevertheless, the hundreds of letters in the Royal Archives between Mrs. Jordan and her royal lover from 1790–1814 testify to the strength and longevity of their relationship. Yet ultimately it seems to have foundered from lack of money as Mrs. Jordan’s acting career came to an end and their debts began to mount. In 1811 the Duke of Clarence coldly began a seven year search to find a rich wife who emerged in the shape of Princess Adelaide Louisa Theresa Caroline Amelia (1792–1849), the eldest daughter of George I, reigning Duke of Saxe Meiningen. They were duly married in 1819 but had no surviving issue. Tonybee in his introduction to the actor Macready’s Diaries, states that ‘it is perhaps not surprising that in after years he (Macready) should have poured bitter contempt on the royal lover who, having profited for years by her splendid earnings, abruptly consigned her to poverty and neglect’. For five years later, Mrs. Jordan died near Paris, in exile, alone, as well as in poverty and misery.

Meanwhile, George, their eldest child, became a soldier by profession and served in the 10th Royal Hussars. In the Royal Archives, there are literally hundreds of letters to him from both his mother and father and these give some account of his military experiences from the age of fourteen when he first sailed for Portugal. His father was obviously proud of him, especially with reports from Brigadier General Charles Stewart, (to whom he was ADC), describing him as a ‘Gallant Fellow’ (RA-GEO/Add/39/07) and writing to ‘express my continued satisfaction and approbation’ (RA-GEO/Add/39/20). His mother’s letters were more critical urging him to pay more attention to his writing and spelling and referring to his bills which she thought ‘extravagantly high’.

He later fought at the battle of Corunna, was wounded and captured by the French at Fuentes de Onoro, but escaped, wounded again at Toulon and later served in India as ADC to the Governor General. On his return from his first term of duty his proud father wrote to his sister Princess Amelia in the following words:

‘I am happy to inform you that George arrived last night in high health and spirits, after having established a perfect character with all ranks in our army’. ‘General Stewart, (later 3rd Marquess of Londonderry), who certainly on one occasion saved his life, speaks of my son in such terms of commendation, that unless writing to you I would not mention the circumstances. Indeed in the event of the General going again he told me he would rather have George than any other for his aide-de-camp’.

Despite retiring on half pay as a Lieutenant Colonel of the Coldstream Guards in 1828, George was appointed Deputy Adjutant General of the Forces in July 1830 but resigned in high dudgeon the following December. Ultimately he was promoted to Major General in 1841 to command Western District, and was appointed Lieutenant of the Tower of London (1831–33), Constable of Windsor Castle (from 1833 with its annual salary of £1,300 and membership of the Privy Council), and ADC to his father and later Queen Victoria. However, after much lobbying, he had had to wait until the advanced age of thirty-seven before he was ennobled as Earl of Munster in 1831 following his father’s accession. Nevertheless, he was disappointed that it was not a dukedom even though it was one of his father’s former titles. He therefore spent the next ten years asking for more. However, despite all these honours and being described in the patent as ‘Our dearly beloved natural son’, he and his brothers were constantly to plague their father for more honours and appointments and more cash, and indeed when George was asked who should carry the Crown at his father’s Coronation, his retort was ‘who is more fit that your own flesh and blood’. The Morning Post was incensed at ‘the impudence and rapacity’ of the FitzJordans, and in the next reign, Queen Victoria was to dismiss her cousins as ‘ghosts best forgotten’.

Much of his time in later life seems to have been spent in pursuit of fame, fortune and honours. He was constantly pressing both his father and afterwards Queen Victoria for financial help and for lucrative appointments for both himself and even his children. In the Royal Archives is a bound book of 113 pages, being A Copy of correspondence between His Majesty King William IV and the Right Honble The Earl of Munster in April and May 1837 relative to a provision for the Earldom of Munster with a commentary thereon and An Appendix containing a copy of a former correspondence upon the same subject (RA-GEO/Add/39/657). This shows in some detail and at great length, how the King had attempted to provide equally for all his children and how Munster was affronted by not having received more on the grounds of primogeniture and the néed to endow his earldom. Indeed, at one stage, he even refused to accept payments on the grounds that they were not enough and for a time he estranged himself from his father.

Queen Victoria’s diaries also make many references to this. On 24 January 1838 the Queen ‘showed him [Lord Melbourne] a letter from Lord Munster to Lord Conyngham expressing his gratitude and wishing to see me to thank me in his own and in his brothers’ and sisters’ names for what I had done for them’ (VIC/QVJ/1838 24 January) – i.e. extending their annual allowances, originally granted by King George IV. Four months later, George was back seeing Lord Melbourne about their FitzClarence pensions from the Civil List. In the diary entry for 15 May 1838 it states that ‘Lord Munster told Lord Melbourne that the late King always imagined that Lord Egremont (his father-in-law) would leave Lord Munster a great deal’ whereas in the event he gave Lord Munster £5,000 about a fortnight before he died. Egremont had long been suspicious that ‘the King had promoted the match on account of the money’. But in September that year, there is a reference to Egremont having given George a property in Somerset.

In 1819 George had married another bastard, Mary Wyndham, natural daughter of the Earl of Egremont (who regarded her as over-religious), by whom he had four sons and three daughters, and indeed one of his grandsons was to be awarded a VC and bar. George was soon busy promoting their interests as well as his own, when writing to his father and later Queen Victoria over the next twenty years, both of whom were remarkably generous and tolerant. Indeed there are many references in Queen Victoria’s diaries to Munster dining at Windsor, including on Christmas Day 1838 when he ‘was in high spirits and talking a great deal’ prompting Melbourne to comment ‘I never knew such a wrong-headed man; he never sees a thing right; and then always thinks he is right.’ (VIC/QVJ/1838 26 December). There are also three large filing boxes of correspondence in the Royal Archives entitled The Munster Papers 1805–41 but they do not cast George in a favourable light.

Sadly George never came to terms with his lot and he was still writing to Lord Melbourne (RA-GEO/Add 39/629) about the possibility of succeeding Major General Sir Henry Frederick Bouverie as Governor of Malta in 1839, and to the Duke of Wellington about money or lack of it as late as 15 December 1841 (RA-GEO/Add 39/637). Three months later, on 20 March 1842, a disappointed man and aged only forty-eight, he shot himself at his home in Belgravia, just five years after his father’s death, and with a pistol presented to him by his uncle George when Prince of Wales. Greville’s Memoirs note that

‘he was a man not without talent, but wrongheaded, and having had the folly to quarrel with his father and estrange himself from Court during the greater part of his reign, he fell into comparative obscurity and real poverty, and there can be no doubt that the disappointment of the expectations he once formed, together with the domestic unhappiness of a dawdling, ill conditioned vexatious wife, preyed upon his mind and led him to this act.

His will was proved at under £40,000 and his widow died nine months later in December 1842. One hundred and sixty years later the Earldom of Munster is now extinct in the male line upon the death in 2002 of the 7th and last Earl, Anthony Charles. He was a graphic designer and a stained glass conservator and he and his ancestors before him, bore the Royal Arms of King William IV, shorn of the escutcheon of the arch treasurer of the Holy Roman Empire and of the Crown of Hanover, but with a baton sinister azure, charged with three anchors or. However, descendants of Mrs Jordan and William IV still survive to this day through the marriages of their many daughters.

The eldest daughter of Mrs Jordan by her Royal lover the Duke of Clarence, later King William IV, was born on 4 March 1795 in Somerset Street, off Portman Square. At the beginning of their association the Duke had given Dora (as he called her) an annual allowance of £1,000, but on the instruction of his father, King George III, the Duke of Clarence then wrote suggesting that he should halve her allowance to £500. By way of reply, Mrs Jordan sent him the bottom half of a playbill bearing the words ‘No money will be returned after the rising of the curtain’.

Sophia was a great favourite with her father and there are many references to her in the letters written by both her father and her mother, all of which are preserved in the Royal Archives. In particular, from 1811 onwards, she spent a great deal of time with her father following the break up of her parent’s long association. Mrs Jordan had negotiated a good settlement whereby the Duke paid £41,360 to produce £4,400 per annum (in a Deed of Covenant and Declaration of Trust, dated 23 December 1811 – RA-GEO/ADD/40/254). However, Sophia and her brothers were excluded, despite the fact that there was provision for her four younger sisters. Unlike her elder brothers, who enjoyed the company of their parents, Sophia seems to have taken her father’s side over the separation, so much so, that Mrs Jordan was forced to declare:

‘To say that Sophy’s conduct towards me is reprehensible to too gentle a name for it. It is shocking to reflect how a young creature can without the smallest remorse break through the first and most sacred tie of human nature. Her selflove seems to have stifled every amiable and natural affection. Poor girl, I lament and pity her, her disappointments must in proportion to her selfishness be severe. She never writes, and at a review, tho’ within our carriage. She left the place to avoid speaking to me. It was taken notice of and mentioned in London. I don’t think even her father could approve of such unprecedented conduct, and that is saying a great deal’

1 Edward IV

2 Arms of Arthur Plantagenet, Viscount Lisle

3 Richard III

4 Henry VII

5 Henry VIII

6 His son Henry FitzRoy, Duke of Richmond & Somerset

7 Charles II

8 His bastards: Sir James Fitzroy, Duke of Monmouth & Buccleuch and his coat of arms

9 His bastards: Sir James Fitzroy, Duke of Monmouth & Buccleuch and his coat of arms

10 Charlotte Howard, Countess of Yarmouth

11 Charles FitzCharles, Earl of Plymouth

12 Anne, Countess of Sussex

13 Sir Charles FitzRoy, Duke of Southampton & Cleveland and his coat of arms

14 Sir Charles FitzRoy, Duke of Southampton & Cleveland and his coat of arms

15 Sir Henry FitzRoy, Duke of Grafton and his coat of arms

16 Sir Henry FitzRoy, Duke of Grafton and his coat of arms

17 Lady Charlotte FitzRoy, Countess of Lichfield

18 Sir George FitzRoy, Duke of Northumberland

19 Sir Charles Beauclerk, Duke of St Albans and his coat of arms

20 Sir Charles Beauclerk, Duke of St Albans and his coat of arms

21 James, Lord Beaucl

22 Lady Barbara FitzRoy

23 Sir Charles Lennox, Duke of Richmond & Lennox

24 Sir Charles Lennox, Duke of Richmond & Lennox

25 Lady Mary Tudor, Countess of Derwter

26 James II

Three of James II’ illegititimate offspring

27 Henrietta, Baroness Waldegrave

28 James FitzJames, Duke of Berwick upon Tweed

29 Katherine, Duchess of Buckinghamshire and Normanby

30 ‘Bonnie’ Prince Charles Edward Stuart

31 His daughter Charlotte Stuart, Duchess of Albany and her coat of arms

32 His daughter Charlotte Stuart, Duchess of Albany and her coat of arms

33 George I and his coat of arms

34 George I and his coat of arms

35 His daughter Petronelle, Countess of Chesterfield

36 George II

37 Frederick Prince of Wales, son of George II

38 George Prince of Wales, later George IV

39 William IV

40 His bastards: George Augustus Frederick FitzClarence, Earl of Munster and his coat of arms

41 His bastards: George Augustus Frederick FitzClarence, Earl of Munster and his coat of arms

42 Sophia, Baroness De L’Isle & Dudley

43 Henry Edward FitzClarence

44 Lady Mary Fox

45 Lieutenant-General Lord Frederick FitzClarence

46 Rear Admiral Lord Adolphus FitzClarence

47 The Rev Lord Augustus FitzClarence

48 Henry Carey, Baron Hunsdon

49 Catherine, Lady Knollys

50 Mary Walter

51 Count Blomberg or The Rev Frederick William Blomberg

52 King Edward VII

53 The arms of the House of Windsor

54 The Hon. Maynard Greville

55 His coat of arms

56 Sonia Rosemary Cubit

57 The arms of the Earls of Albemarle

58 Prince Albert Victor Christian Edward, Duke of Clarence & Avondale

59 David, Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII and Duke of Windsor

60 (William) Anthony, 2nd Viscount Furness

61 Timothy Ward Seely

Mrs. Jordan was obviously very distraught about the split and wrote to the Duke expressing her feelings thus: ‘on the eve of quitting this place for ever (Bushey Park) with sensations of regret and pleasure scarcely describable’.

But at least the Duke, unlike his brother King George IV, did ensure that his children were publicly acknowledged upon his accession. As with her siblings, Sophia was granted by Royal Warrant in 1831 the precedence of a younger child of a Marquess and in 1818 all five sisters were granted a pension of £500.

Rather surprisingly, Sophia did not marry until she was thirty years old. Her husband Philip Charles Sidney, of an illustrious family, was five years younger than his bride, and it was not until 1835, ten years after their marriage, that he was raised to the peerage as 1st Baron De L’Isle and Dudley, of Penshurst He was successively an equerry to the King (William IV), a Lord of the Bedchamber and Surveyor General of the Duchy of Cornwall and had been appointed KCH and GCH.

Despite her advanced age, which curiously was the same as when her mother began her association with the Duke of Clarence, the marriage produced a number of children including two daughters. Of these, Adelaide, named in honour of the Queen, married her cousin Frederick FitzClarence but died without issue; and Sophia married Count Alexander Kielmansegg, a descendant of Sophia Dorothea Kielmansegg, half sister of King George I.

Sadly Sophia died at the early age of just forty-two, at Kensington Palace on 10 April 1837, having recently been appointed ‘Housekeeper’ thereof, and there is a brief reference to this in Queen Victoria’s diaries. Indeed it was reported at that time that she was the favourite of her Royal father and that she had occasionally acted as his amanuensis. But only two months after her death, she was followed by her father King William. From her only son, descends the present representative of the Sidney family, Sir Philip John Algernon (Sidney) 2nd Viscount (born 1945), and Sophia’s portrait is in pride of place at Penshurst Place.

Henry Edward FitzClarence, was born on 8 March 1797 at Richmond, Surrey, the third child and second son of William, Duke of Clarence and Mrs Jordan. His arrival in the world was noted in the 13 March 1797 edition of The Times:

‘Little Pickle was brought to bed on Tuesday last of a son, at the Duke of Clarence’s house on Richmond Hill. This is her third child by the Duke’

Little Pickle, of course, was Mrs Jordan’s nickname given to her by The Times from the part she played in The Spoiled Child. Clarence wanted this son to serve in the navy as he had done, and when the boy was just ten years old he approached his old friend Rear-Admiral Richard Keats and requested his help:

‘I am anxious to send Henry to sea and ultimately he shall go, but mothers must be consulted. Unfortunately I am afraid there is too much reason to believe that I have lost an unfortunate boy on board the Blenheim which naturally enough causes great uneasiness to Mrs Jordan and makes me cautious as to my method of proceeding relative to Henry ... The boy himself is delighted with the idea and talks of you and the Navy with rapture’.

At the tender age of twelve, his father’s wish was eventually granted when he purchased a commission in the Navy for him and young Henry became a volunteer on the ship Mars, Admiral Keats’s flagship. Despite her misgivings Mrs Jordan was pleased that her son was in the Admiral’s care for

‘the attention and kindness of Admiral Keats to all the boys is more like the affectionate care of a father than master’.

Henry’s first stint of duty was in the Baltic whence Admiral Keats had been sent to rescue 9,000 stranded Spanish troops in Denmark with their artillery and baggage. He followed this up, after just ten days leave, with another in the ill-fated Walcheren expedition lead by the Earl of Chatham, with Keats as second in command of the Fleet under Admiral Strachan. On his return in November 1809 he was granted six months leave before returning to serve on the Warspite in the Mediterranean. The next five months were spent blockading Toulon but despite his commanding officer’s high regard for him, the latter’s reputation for flogging his midshipmen prayed on the young boy’s mind and he asked to be transferred. ‘I wish he was with Keats,’ wrote his mother, ‘before anything unpleasant happens, for he declared in his letter to Sophy (his elder sister) that if they attempted to flog him he would run away, and you know how violent he is’.

Henry later transferred to the Army where he served in the 10th Hussars, the same regiment as his elder brother George, and there are a number of letters in the Royal Archives which their father wrote to them jointly. Henry appears frequently in his mother’s letters to other members of the family. He was constantly in néed of money and often wrote asking her to send some ‘Henry is in great want of money, and concludes his catalogue with ‘send plenty of money’. Poor fellow-he does not seem to know that it is rather an expensive article and not always to be found. However he shall (have) some’. In 1813 she duly noted that Henry was about to go abroad again ‘Henry goes to Lisbon with Lord Beresford, a very good thing for him’

His next military expedition was with the army which invaded Southern France. When his regiment returned, he, together with a number of his fellow officers, accused their colonel, George Quentin, of professional incapacity claiming that he ‘did not make necessary and proper arrangements to ensure success.’ When the Colonel was found guilty, Henry’s uncle, the Duke of York was furious that junior officers should accuse their superior officer and saw to it that all twenty-five officers were dismissed from their regiments including Henry, the latter being ordered to India. To add insult to injury the Prince Regent’s private secretary penned a letter to his new commanding officer ‘begging that the strictest discipline, not to say severity, should be exercised towards them in consequence of their share in the business of the 10th Hussars’. To his credit the commanding officer rejected such a proposal replying that he ‘had received the Colonel’s letter, and that he should have returned it with the contempt it deserved, but that he chose to retain it, that he might have it in his power to expose him, should such unfair and offensive conduct be repeated’.

Fortunately none of these proceedings affected the small annuity of £200 that Henry received from his uncle the Prince Regent. Sadly, however, young Henry died of a fever in 1817 aged just twenty and unmarried, and just one year after his mother. At the time of his death, he was an ADC to the Governor-General, the Marquess of Hastings, who wrote of his own feelings for the young man: ‘I have been pained by the death of Lieutenant Henry FitzClarence … He was a mild, amiable young man, earnest in seeking information, and in improving himself by study’.

The second daughter of Mrs. Jordan, by the Duke of Clarence, later King William IV, Mary was born on 19 December 1798 at Bushey House, Bushey Park, where her parents had set up home when her father was appointed Ranger of Bushey Park in January 1797. As with her siblings, she was granted by Royal Warrant in 1831 the precedence of a younger child of a Marquess and in 1818 all five sisters were granted a pension of £500. She was also granted a differenced version of the Royal Arms charged with a baton sinister azure charged with an anchor between two roses or.

Like her eldest brother, in 1824 she too married a bastard, General Charles Richard Fox, MP, Colonel of the 57th Foot, Receiver General of the Duchy of Lancaster, and a well known archaeologist, who died in 1873. He was the natural son of Henry Richard (Fox), third Baron Holland, who was an old friend of her father’s and who had married in 1797 the divorced wife of Sir Godfrey Webster, 4th Bt. Prior to this, Sir Godfrey had been awarded £6,000 in damages against Lord Holland, because of the son Charles that he had had by Sir Godfrey’s wife. It was reported that ‘Sir Godfrey Webster with difficulty, and after some time was bribed to divorce her by the surrender of her fortune’. The Third Baron was also a great-grandson of the 2nd Duke of Richmond, a grandson of King Charles II.

There are a few mentions of the Foxs in Queen Victoria’s diaries. Like her siblings, Mary and her husband dined at Windsor from time to time and on 16 February 1839 The Queen described her as ‘poor Lady Mary Fox’ and as being ‘very much affected but very kind; she is a very nice person’ and ‘her voice being like her sisters. Lord M (Melbourne) knows her the best of any and says she is the cleverest of them’ (RA-VIC/QVJ 1839 16 February)

On 23 June 1839 there are references to Mary having abused The Queen Dowager and Lady Holland too and being described as ‘a very eager person’. She died aged 66, some nine years before her husband and relatively little seems to have been recorded about her.

Frederick FitzClarence was born 9 December 1799 at Bushey House, the third, but second surviving son of Mrs. Jordan (1761-1816), the well known comic actress, by her Royal lover the Duke of Clarence, later King William IV.

Like his elder brothers, he was destined for a career in the Army and first appears on the pages of history when he was drafted to serve in the Waterloo campaign. The resumption of the war was obviously of some concern to his mother who wrote to her younger son Adolphus: ‘Dear Frederick has joined his regiment at Brussels in consequence of the renewal of this cruel war’. However, she néed not have worried as Frederick remained safe and his conduct was exemplary:

‘Frederick’s Col. Had written a very handsome letter to your father, relative to Frederick’s conduct on the march to Ramsgate of the Guards, who behaved very ill, got drunk and were near mutiny. Frederick stayed behind and by his zeal and activity prevented much disorder and confusion’.

After Napoleon’s defeat, young Frederick entered Paris with his regiment, only to discover that his mother had fled England to avoid her creditors. Concerned he discovered her whereabouts and wrote to her

‘Tell all about the Marchs. If you want money for them don’t ask me for it, but take my allowance for them; because, with a little care I could live on my father’s till their business is a little settled. Now do as I ask you mind you do; for they have always been so kind to us all; and if I can make any return, I should be a devil if I did not. So take my next quarter and, as you may not want to give them some, do that for my sake’.

Eventually Frederick rose to the rank of Lieutenant General. At one time he had commanded the forces of Bombay and was Colonel of the 36th Foot. Although he was appointed GCH (Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Hanoverian Guelphic Order), he bombarded his father with requests that he should be made a Hanoverian general as well. But Melbourne was not impressed by him, describing him as ‘very foolish’.

As with his siblings, he was granted by Royal Warrant in 1831 the precedence of a younger child of a Marquess and with a special remainder to the Earldom of Munster, failing the heirs male of his eldest brother. He was also granted a differenced version of the Royal Arms charged with a baton sinister azure charged with two anchors or. He and his siblings do appear to have had some contact with Queen Victoria, in that there is an entry in her diary dated 22 February 1838 recording the fact that he had dined with her. He married in 1821 Lady Augusta Boyle (who died on 28 July 1876), daughter of the 4th Earl of Glasgow and he died aged fifty-five on 30 October 1854, leaving a daughter who died unmarried.

The third daughter of Mrs. Jordan (1761–1816), the well known comic actress, by the Duke of Clarence, later King William IV, was Elizabeth FitzClarence, who was born on 17 January 1801 at Bushey House. As with her siblings, she was granted by Royal warrant in 1831 the precedence of a younger child of a Marquess, although her subsequent marriage gave her a higher precedence. In 1818 all five sisters were granted a pension of £500. She was also granted a differenced version of the Royal Arms charged with a baton sinister azure charged with an anchor between two roses or.

Elizabeth married in 1820 William George (Hay), eighteenth Earl of Erroll, KT, GCH, Hereditary High Constable of Scotland, who later served as Lord of the Bedchamber to her uncle King George IV and Master of the Horse to the Queen Consort and Lord Steward of the Household. He was created Baron Kilmarnock and appointed KT and PC among many other honours. Like her siblings, Elizabeth features in Queen Victoria’s diaries when she dined or stayed at Windsor. For instance on 7 December 1838 the entry reads:

‘Saw Lady Erroll who had not yet seen me since the King’s death, and seemed much affected but conqured herself; she was very kind and kissed and pressed my hand and said she could not express all she felt; she is grown enormously large. At 10m to 8 we dined …I sat between Lord Albemarle and Lord Erroll and we talked literally of nothing but racing, hunting, horses, breeding horses etc, etc’ (RA-VIC/AVJ/1838 7 December).

On 4 January 1840 they were dining again when The Queen described her as ‘such a nice, natural person’.

Six years later in 1846, Lord Erroll died of diabetes leaving a son and two daughters, one of whom married Charles Edward Allen, the self styled Count d’Albanie, who claimed to be the legitimate grandson of Bonnie Prince Charlie, but was in fact an imposter, another was a bridesmaid to Queen Victoria. Elizabeth survived her husband for nine years, dying in 1856 and for some of this period she was living at one of the lodges in Richmond Park.

The present representative of this illustrious and ancient family is her great-great-great-great-grandson, Sir Merlin Sereld Victor Gilbert (Hay), 24th Earl and Hereditary High Constable of Scotland, (born 1948) who is also the grandson of the Lord Erroll of ‘White Mischief’ fame. Another descendant, through their daughter Agnes who married 5th Earl of Fife, is the leader of the Conservative Party, David Cameron.

The fourth son of Mrs. Jordan (1761–1816), the well known comic actress, by the Duke of Clarence, later King William IV, was Adolphus, who was born on 17 February 1802 at Bushey House and named after his uncle the Duke of Cambridge. In 1808, his mother describes him as ‘really the very finest child I ever saw and certainly the handsomest of all mine’ (GEO/Add/40/19a). Indeed, of all her children Adolphus was the one she loved the most, and surviving letters at Wemyss Castle testify to their closeness. The first, dated 1813, was written from Margate:

‘I trust and believe my dear and darling boy will not impute to neglect or want of affection my silence. I waited till I could see dear Henry to learn from him how and when I could best write to my dear affectionate Lolly [Adolphus]. All the children I saw and dined with at Lloyd’s on Friday last, except George, who is gone to Brighton to join his regiment, but he is to be on duty immediately at Hampton Court. The dear children are all well. Henry made me very happy by giving me hopes that the war with America will soon be over, in which case I shall soon see you.’

The following year, however, aged only twelve, Adolphus joined the Royal Navy and served on board the Impregnable, the Newcastle, the North American Station as a Midshipman, in the Tagus, and the Rochfort, Flagship of Sir Thomas Fremantle, and the Glasgow, all in the Mediterranean.

The fact that he saw soo much service in the Mediterranean gave him little practice in coastal navigation. To remedy the situation his then commanding officer Admiral Fremantle arranged that he be transferred to the sloop Aid under the watchful eye of Captain Smyth ‘a remarkably good astronomer, draughtsman and surveyor’; the sloop was to be employed off the Ionian Islands and the Adriatic. In the Admiral’s opinion

‘if these young men [his own son Charles included] are disposed to learn, they can never have a more favourable opportunity. Indeed it is on the score of navigation they are both deficient which is to be accounted for by their serving so much in the Mediterranean out of sight of land’.

His interest in Adolphus was amply rewarded and in a letter to his brother in October 1818, Fremantle wrote: ‘If you should see the Duke of Clarence you may mention that I am quite satisfied with his son(s) who are improving daily’.

The anxiety of Adolphus joining the Navy at such a tender age was compounded when Mrs Jordan received news that her eldest son had been wounded in action. ‘I have been quite ill, but thank God, all my anxiety about dear George has this moment been removed by a letter from the dear fellow wherein he says he is pronounced out of all danger’. Apparently the wound was received during the capture of Toulouse ‘ I lose not a moment in relieving your anxiety about dear George, who tho’ he has been severely wounded in the thigh is, thank God, in a fair way of being well’.

Adolphus’s first commission as Lieutenant was dated April 1821 following which he joined the Euryalus and then the Brisk sloop and Redwing on the North Sea Station before being promoted to the rank of Commander. In 1824 he achieved the rank of Captain and was given command of the Ariadne in the Mediterranean, the Challenger and the Pallas and from 1830 the Royal George and Victoria & Albert yachts. There are a number of references to Lord Adolphus in Queen Victoria’s diaries including an entry for 1 Spetember 1842 in which she says ‘how highly satisfied we both were with extreme attention and assiduity of Lord Adolphus and all the officers’. But another entry for 29 August 1838 records that Melbourne thought him ‘mad’.

He eventually rose to the rank of Rear Admiral of the White, being appointed in 1853, some twenty-nine years after first being promoted Captain. He had also been appointed Groom of the Robes and a Lord of the Bedchamber to his father, King William IV, GCH, ADC to Queen Victoria and Ranger of Windsor Home Park. Like his siblings, he had, on his father’s accession to the Throne in 1831, been granted by Royal Warrant the precedence of a younger child of a Marquess and with a special remainder to the Earldom of Munster, failing the heirs male of his eldest brother. Like his siblings, he was also granted an annuity by his uncle King George IV and this was continued by both his father as well as by Queen Victoria. He was also granted a differenced version of the Royal Arms charged with a baton sinister azure charged with two anchors or.

Nevertheless money always remained a problem for him, especially as he was perhaps the least acquisitive of his siblings. Indeed Queen Victoria notes in her diary on 23 January 1838 ‘I told Lord Melbourne that Lord Adolphus FitzClarence on being told that I would continue to him and his brothers and sisters the same annual allowance they enjoyed from the late King, burst into tears and said that it was unexpected, for they did not dare to hope for anything’. However upon the suicide of his eldest brother in 1842, it fell to Adolphus to have to deliver his brother’s letter to the Queen asking that she might extend his pensions to his children, something she did not feel inclined to do, and supported in her decision by Melbourne and Sir Robert Peel. As a sop, however, she did offer to do what she could for them in their respective professions, although she clearly thought that it was remarkable of Lord Munster ‘going and premeditatingly shooting himself and then asking me to take care of his children’.

Yet sadly, when Adolphus died, unmarried, on 18 May 1856, his assets proved insufficient to pay his debts, funeral expenses and legacies. (RA-GEO/Add 39/668). Meanwhile, Queen Victoria’s diary entry for the following day (page 218) provides a suitable epitaph in which she says

‘Poor Ld Adolphus FitzClarence, of whose paralytic seizure we heard on the 17th, died yesterday evening. We are truly sorry as he was very good natured and kind hearted, but he positively killed himself by living too well. He was only 54, though he looked quite 10 or 12 years older’.

The fourth daughter of Mrs. Jordan (1761–1816), the well known comic actress, by the Duke of Clarence, later King William IV, was Augusta FitzClarence, who was born on 17 November 1803 at Bushey House. As with her siblings, she was granted by Royal warrant in 1831 the precedence of a younger child of a Marquess and in 1818 all five sisters were granted a pension of £500. She was also granted a differenced version of the Royal Arms charged with a baton sinister azure charged with an anchor between two roses or.

Very little seems to be known about Augusta and there were no references to her in Quen Victoria’s Diaries. Augusta married twice, firstly in 1827 to the Hon. John Kennedy-Erskine, 2nd son of Archibald (Kennedy), KT, FRS, 1st Marquess of Ailsa and 12th Earl of Cassilis. Her husband, who had inherited his maternal grandfather’s estate of Dun in Forfarshire when he added the name and arms of Erskine of Dun, died four years later, leaving a son and a daughter, Wilhelmina (who was to marry in 1855 her first cousin the 2nd Earl of Munster). As chatelaine of the House of Dun in Angus, Augusta became a passionate botanist and néedlewoman and features in Great Houses of Scotland by Hugh Massingberd.

She married secondly on 24 August 1836 a professional sailor with service in the Home, South American and Mediterranean Stations, who saw action with the Toulon fleet in 1814. He was Captain, later Admiral, Lord John Frederick Gordon, who in 1843 changed his name to Hallyburton. He was the 3rd son of the 9th Marquess of Huntly and 5th Earl of Aboyne and he later served as an MP for Forfar in Angus. Three weeks before their marriage, he went on half pay, having paid off the sloop Pandora, and just a week before he was appointed GCH. Nevertheless his half pay did not prevent him being promoted successively Rear Admiral in 1857, Vice Admiral in 1863 and full Admiral in 1868. Augusta died in 1865 without any further children but he survived her for another twelve years thereafter.

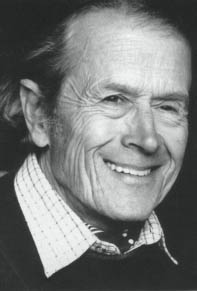

The fifth and youngest son of Mrs. Jordan (1761–1816) and the Duke of Clarence, later King William IV, was Lord Augustus FitzClarence, who was born in London on 1 March 1805. He was educated firstly at Wimbledon and then went up to Braesnose College, Oxford where he matriculated in 1824, moving on to Trinity College, Cambridge two years later. There he was awarded an LLB in 1832 and an honorary LLD in 1835.

It was William IV’s intention ‘to make five sons of mine fight for their King and Country’. However fate decreed otherwise and in the event two sons served in the army, four in the navy and one the church. From the moment of his birth William was particularly anxious that Augustus should serve in the Navy, and he was just twelve years old when he joined the frigate Spartan as a volunteer first class on 13 February 1818. Within the year William was writing to Admiral Fremantle requesting that he take on Adolphus and Augustus as midshipmen:

‘Captain Green having assured me you are kind enough to keep the situation of rated Midshipman on board your Flagship for my son Adolphus who is now with Dundas in the Tagus and has already served four years of his time, I have only to thank you for this act of friendship. But I must request your attention to my other son Augustus who has just entered into our service … I am anxious that he should have the advantage of education under Captain Green and the Chaplain, and to participate in the various branches of foreign languages which will be pursued on board your Flagship’.

Augustus joined the Rochfort, Fremantle’s flagship, as a Midshipman on 29 October 1818 and his brother Adolphus followed early in 1819. Unfortunately Augustus’s naval career was cut short and he left the service in 1821. The reason he gave was that:

‘he had been trained as a sailor, the navy being the career that he preferred above all others, but that in consequence of the death of a brother he had been literally taken from on board ship and, in spite of the utmost reluctance on his part, compelled to go into the church … He had not been bred to the church and had the greatest disinclination to taking orders’

Another variation of this theme is found in Alumni Cantabrigienses which states:

[He also] had a great devotion for celebrated actresses, including Fanny Kemble (1763–1841), who ‘he had asked to write a sermon for him, which she indignantly declined to do. He made a successful and very generous parish priest’. If Fanny Kemble is to be believed, he also ‘had a charming voice that, my father said, came to him from his mother’ and he was ‘pleasant looking, though not handsome… ‘

As his half brother, William Courtenay had died 1807 aged nineteen, when Augustus was only two, the death of his brother to whom he must have been referring was Henry FitzClarence who died unmarried in 1817 aged twenty, when Augustus would have been only twelve, and a year before he himself joined the Navy. This was some four years before Augustus left the Navy and seven years before he went up to Oxford, so his reasoning did not ring true.

After his time at both Oxford and Cambridge, Augustus was indeed ordained a priest and The Clergy List records that he became Vicar of Maple Durham, Oxford in 1829 (aged only twenty-four). This parish (value £878 with a population of 481), was in the gift of Eton College, and there he remained for the next twenty-five years until his death.

Despite having been granted by Royal Warrant the precedence of a younger child of a Marquess upon his father’s accession to the Throne in 1831 as his siblings had been, and a differenced version of the Royal Arms charged with a baton sinister azure charged with two anchors or, he too was dissatisfied and lacking in humility, for he demanded promotion and was then apt to be insulted by what was offered to him, having indignantly rejected offers at Worcester Cathedral and the post of Canon of Windsor. However, he did accept the appointments as Chaplain to his father and thereafter to Queen Victoria from 1840–52.

Some four years before he eventually married, Macready, the actor, says in his Diaries that, in 1841, the Reverend Augustus made a declaration of love to Miss P. Horton, an actress; that he was far more familiar with the stage than the pulpit – and that he made up for the paucity of his sermons by the eloquence of his ‘billets doux’ (part of which are cited in GEO/Add/40/255). He was married later in life, aged forty, on 2 January 1845 to Sarah Elizabeth Catherine (who died 1901), eldest daughter of Lord Henry Gordon, the fourth son of the 9th Marquess of Huntly, and he died nine years later on 14 June 1854, aged only forty-nine, leaving issue of two sons (neither of whom had any surviving male issue) and four daughters. Of the latter, only Dorothea, who married in 1863 Captain Thomas William Goff, DL, (1829–76) of Roscommon, left issue and living descendants.

The fifth and youngest daughter and the tenth and youngest child of Mrs. Jordan (1761–1816), the well known comic actress, by the Duke of Clarence, later King William IV was Amelia, who was born 21 March 1807 at Bushey House. As with her siblings, she was granted by Royal Warrant in 1831 the precedence of a younger child of a Marquess and in 1818 all five sisters were granted a pension of £500. She was also granted a differenced version of the Royal Arms charged with a baton sinister azure charged with an anchor between two roses or.

Amelia, who was given away by her father, married in 1830 at the Royal Pavilion, Brighton as his first wife Lucius Bentinck (Cary) 10th Viscount of Falkland, PC, GCH, head of an old family dating back to the fourteenth century. He had succeeded his father, who had been killed in a duel, and later served as a Lord of the Bedchamber to his father-in-law, as well as Governor of Bombay. He was also created Baron Hundson of Scutterskelfe in 1832.

There are a number of references to the Falklands in Queen Victoria’s diaries when staying or dining with her. Clearly the Queen had a soft spot for Amelia, whom she described as ‘such a nice unaffected person’. When dining with The Queen on 14 April 1838 at Windsor, Queen Victoria was concerned to find Amelia ‘very much overcome indeed at dinner, poor thing, not having been here since she left Windsor after the poor King’s funeral. She cried, I observed, but really behaved very well and unaffectedly and tried to conquer her feelings which must have been very painful and acute.’

Amelia died in 1858 aged fifty-one, leaving an only son, Lucius, who himself was to die without issue. However as a small boy he captured the heart of the new Queen Victoria who described him variously as ‘a dear boy’, ‘a beautiful child’, ‘a remarkably nice boy, so natural and not at all shy’. Lord Falkland, who was much in demand as a family trustee and executor, then went on to marry Elizabeth, widow of the 9th Duke of St Albans (see page 75).