14

SELECTING THE DOZEN

Kevin and I had a working dinner alone that night. We only had one more day to spend in the cellar – Tamaz, Revaz and union ladies permitting – and so we wanted to make sure we didn’t waste it. This night was a chance to take a breath and reconcile our thoughts and impressions, compare tasting notes and reflect on where our strategies and agendas were at. We half expected another phone call from George, telling us to be out the front for another crazy night-time adventure, but it didn’t come. Maybe George needed a night off as well. Maybe George was at the opera with Natascha and his girlfriend. Or maybe George had a wife and five children that we hadn’t heard about.

Kevin looked across the table at me, our plates pushed to the side to make way for all our notebooks and paperwork.

He said, ‘You realise we still haven’t broached the most fraught subject of them all.’

‘Whether the people we’re dealing with are the Georgian mafia?’

Kevin snorted. ‘Oh, I’m way past that.’

‘Okay then, who actually owns the cellar and who can negotiate the sale of the wines?’

He laughed. ‘That is a good one, but mine is more immediate than that,’ he said.

‘Okay, then what’s the other fraught question?’ I asked.

Kevin said, ‘How do we convince everybody not named George to honour our pre-trip deal, that we can take at least a dozen antique bottles with us when we leave?’

I sipped my Georgian rosé. ‘Yeah, I’ve been thinking about it a lot. It’s essential that we have those bottles. I guess it’s going to take money. That’s what seems to solve every other issue around here, like today with that tasting fiasco.’

‘We need to have a decent amount of American currency on us tomorrow, just in case,’ Kevin said. ‘And we need to have a list of the wines we’d like to take, so that there’s as little room for debate as possible.’

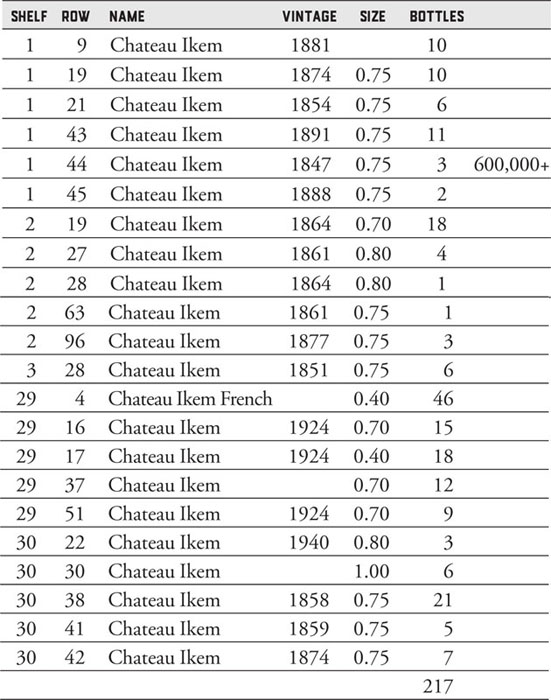

‘We talked about all this before we even got on the plane, remember?’ I said, shuffling through my notebook. ‘Here it is. I wrote down that we’d agreed on several criteria for choosing them. The first is to pick bottles that have features, characteristics or ways of being authenticated as completely as possible, so that we can reduce any ambiguity on whether the collection is genuine. We certainly want some Yquem as it is the basis of the value in the cellar. The list says there are 217 Yquems from the 1800s and 1900s, and there may be vintages that the château itself may not have in their own library.’

‘The second is to pick bottles that show the range of the cellar to a potential auction house like Christie’s.

‘The third is to choose bottles that are valuable in their own right, so that if this entire venture goes belly up, which, let’s face it, it still very well might, we have in our possession some bottles that on their own could sell for enough money to cover the costs of this trip, the expense of setting up the partnership and other costs incurred so far.

‘My final note in my notebook,’ I said, pretending to squint as I peered at the page, ‘was a comment from one Kevin Hopko, Esquire, who said we should retain the right to not sell all twelve bottles, because they could also be the basis of a really spectacular dinner party with friends.’

‘And I stand by that comment,’ Kevin said. ‘You’re lucky to have me, for my mature and sensible alternative viewpoints.’

‘So, if we look at the bottles we’d like, we should start with two dozen and potentially get talked back from there to twelve,’ I said. ‘Further, we don’t want Georgian wines, we want old Bordeaux or Yquem because ideally we want to have ones that can be chemically tested to establish that they’re genuine, and anyway, with so much century-old Yquem in that cellar, we really want to take some with us.’

We sat and went through the wines that we had cross-referenced as matching the cellar book over the last two days. A list began to take shape.

We decided that an 1877 Lafite would be a solid choice, for individual value, impressing an auction house and the ability to be authenticated. An 1884 Margaux made the list and then we pondered the various Yquems. Those three tantalising bottles of 1847 Yquem hovered in my consciousness. Was there any chance the Georgians didn’t realise the rarity of that trio of bottles? Would they let even one fly away?

We agreed we didn’t need to choose another 1899 Suduiraut, as much as I’d have loved to have that bottle sitting in my cellar at home, not only because of how good it was but also for the memory of the moment we tasted the dropped wine and the lights went on that the cellar may be real. However, the fact was that we had already tasted it and felt there was no question it was genuine, so maybe other bottles could tell us more?

As we tried to put our two dozen dream bottles together, we realised that we still had some important wines to inspect on the last day, representing sizeable amounts of the value in the cellar, as far as we could tell from our translated list.

Kevin and I went over the pages for the thousandth time.

‘Shelf number two, wine number twenty-seven is four bottles of 1861 Yquem,’ I said. ‘We definitely need to check those.’

‘Shelf number three, wine number twenty-eight is also Yquem, 1851,’ Kevin said. ‘We also need to check those.’

I smiled. ‘Shelf number thirty, wine number thirty is also Yquem but doesn’t have a vintage listed. I guess we should check on those and see if we can discern the vintage from the corks.’

‘I think we should,’ Kevin said. ‘What do you think the chances are of us actually receiving a list of Stalin’s personal collection tomorrow, in a language we can read?’

‘About the same as us walking onto the plane with two dozen bottles of 150-year-old Yquem,’ I replied.

Kevin lifted his glass of rosé. ‘I think you might be right.’

‘Do you want dessert?’ I asked him. ‘They have crème brûlée.’

Kevin shook his head and looked wary. ‘I never trust a dessert that wobbles,’ he declared definitively.

What do you even say to that? I ate dessert alone.

Pyotr picked us up in the delivery van the next morning. As soon as I saw him, I noticed that he seemed coiled like a spring. While he had been hugely helpful to us and mostly friendly, Pyotr definitely had a steelier edge to him. We watched as he argued with the hotel security guard about leaving his gun behind to join us in the lobby. He’d left his gun without complaint before, so it made me wonder about his mood today. As before, the security staff all tuned in to Pyotr’s presence in a way they didn’t when Nino or Zurab came through the front door.

We saved the guards from a potential stand-off by walking through security to meet Pyotr on the street, and he seemed friendly enough to us. His driving was more sedate that Nino’s as well, which was another relief.

We exchanged pleasantries with Tamaz and Revaz at the winery and headed for the cellar. All rancour from yesterday’s umbrage at our alleged brazen drinking of the collection seemed to have evaporated, but Revaz indicated he’d be coming with us today, which annoyed me because we were on the clock, with only today to dive into the collection, and the chief winemaker was incredibly slow and ponderous to have involved.

I asked Pyotr to gently explain to Revaz that we were deeply concerned not to have seen details of Stalin’s personal collection, after several days of asking, and a full day since we sent a Georgian version to be translated. What I didn’t ask Pyotr to translate was my urgency to assess the collection because those bottles were no longer just bottles of wine. They were Russian memorabilia, a true collectable with Stalin’s provenance. They were essential to our endeavour.

The temperature of the cellar on that final day was really chilly, so we found ourselves in thick jumpers and wondering if we could see our breath in better light. Possibly shamed by the fact that they had failed to hand us the Stalin list, Revaz produced a more detailed list than we’d ever seen of the wines in the lower basement. We spent the morning down there, ticking off several Yquems, a Lafite and other classics.

As per the previous two days, I was still on high alert for a sign, any sign, that this cellar was not legitimate. Kevin and I only needed one bottle of alleged Bordeaux that was in the wrong-shaped bottle or the wrong colour or had a suspicious cork, and internal alarm bells would have gone off that this may not be all it appeared or was alleged to be. However, the lower basement seemed as well chronicled and legitimate in every way as the main cellar above.

We had lunch at a cafeteria not far from the Savane winery, with Pyotr and a friend of his, a guy in a large overcoat which he didn’t take off, even in a warm restaurant, for the duration of the meal. Kevin had a quiet word in Pyotr’s ear as we were getting ready to head back and so we drove away from the winery. ‘I thought we had better get some money,’ Kevin said to me quietly, as we sat in the back, with Pyotr and his friend up the front. ‘Pyotr seems to know where we should go.’

We stopped at an antique shop and Pyotr said a few words to his overcoat friend, who got out of the car and lounged against the wall of the shop, by the front door. I wondered if he had a submachine gun under that coat. Nothing would have surprised me.

The antique shop was fantastic. I, but particularly Kevin, could have stayed there all day in other circumstances. It had everything from the standard terrible vases and lamps, old books and trinkets that seem to be in antique shops the world over, to a large collection of rifles, pistols, swords and other military hardware. Some of it looked to date back centuries, while other guns and uniforms were much more modern, either from World War Two or even more recent, to my untrained eye.

‘We might need one of these,’ Kevin said, pointing to a small novelty pistol with two barrels that diverted halfway down the gun and would apparently shoot at 45-degree angles to one another. ‘In case Tamaz and Revaz charge us at the same time,’ he said.

Pyotr had gone over to the counter and was having a quiet word with the owner, who disappeared into a back room. Pyotr called Kevin over, and asked for his traveller’s cheques. As I checked out revolutionary swords, they went into a huddle and then Pyotr shook hands with the owner and we all marched out of the shop. Overcoat Man had barely moved a muscle and stayed at his post, both hands still hidden in the folds of his coat, until the three of us were safely in the car. Then he sauntered to the passenger seat and got in, for Pyotr to drive away.

Kevin leaned over to me and said, ‘We either just robbed that antique store or my traveller’s cheque receipts just lit up on international cybercrime networks across the globe, or maybe both.’

‘How much money did you get?’ I asked.

‘One thousand American dollars,’ he said.

I lifted my shirt slightly so Kevin could see the bandage-brown line of a pouch hidden under the line of my jeans. ‘Then we’ve got two thousand dollars if we need it,’ I said.

Kevin looked genuinely amazed.

‘Have you been carrying that around the whole time?’ he asked. ‘Surrounded by guns and hoodlums and in a town like this?’

‘Without blinking,’ I said.

When we returned to the winery, a miracle occurred. George was there and handed us a stapled collection of pages that turned out to be the translated English version of Stalin’s personal collection.

‘This is what you needed, yes?’ he said. ‘Just remember that I, your favourite George, am here to help you. Forever, and always, at times.’

‘That’s good to know, George. Thank you,’ I replied. ‘And on that, while you’re here, we need to talk about the wines we’re leaving with tomorrow.’

‘Leaving?’ He looked confused.

‘Remember, in the deal, before we came to Georgia, we discussed that we would need to take some of the antique wines home with us, to have them tested, to prove authenticity and to convince our partners that this entire cellar is legitimate and that we can feel safe in buying it.’

‘What kind of testing?’ he asked.

‘There are a couple of ways,’ Kevin said. ‘All organic materials, whether in wine or not, contain a radioactive isotope carbon 14, and it decays at a known rate, meaning chemical testers can measure wine, measure the rate of decay and know roughly how old the liquid is.’

‘Okay,’ said George.

‘It’s kind of cool because when nuclear tests happened in the 1950s and 1960s, that pushed the worldwide levels of carbon 14 up at that time, so really, the wines in your cellar shouldn’t reflect that. If they do, they’re younger than the fifties and we have a problem.’

‘Okay,’ said George again.

‘Tritium, too, is another measure that shouldn’t register as particularly high if the wines are genuinely more than a century old,’ Kevin continued.

‘Okay,’ said George, nodding.

‘Of course, there is also a scientist, Hubert, in France who uses low-frequency gamma rays to test wine without even opening the bottle,’ Kevin said. ‘By directing the gamma ray at the wine, he can detect whether the radioactive isotope caesium-137 is present, which can only happen as a reaction of nuclear fallout so, again, if the wine here is genuinely dating back to pre-1900, that isotope cannot be present.’

‘Okay,’ George said.

‘Kevin, I don’t want to burst your scientific bubble but I think George understood about 3 per cent of what you just said,’ I pointed out.

‘Oh, okay, sorry,’ said Kevin. ‘George, the short version is we really need to test the wine.’

‘Yes, I not understand specifics, but I can see the need,’ George said, frowning. ‘However, this might be difficult.’

‘George,’ I said. ‘You never mentioned that there were other owners of the winery or that we’d have to deal with people like Tamaz. You need to make this happen. I’m not being overly dramatic when I say that if we don’t have bottles with us when we leave, this entire deal will fall through as we won’t be able to prove that the wines are genuine. No million dollars from us.’

‘How many bottles do you want to take?’ he asked.

‘Ideally, twenty-four.’

‘Twenty-four!’ He sounded as though I’d said half the cellar. ‘That’s a lot of bottles.’

‘We need to show the variety of wines within the cellar. We need to show that they can test any of these wines and they are what we claim them to be. We need a show of faith from you and your people, George.’

George thought for a long moment and then sighed. ‘John, I understand. I remember our earlier discussion. I did not realise you were talking about so many bottles, but first things first. I will start the explanation to Mr Tamaz and the others.’

‘Thank you, George. It’s very important.’

‘I do not think you’ll be able to take any of the Stalin collection,’ he said, pointing to the pages I held.

‘Okay, well, let me see what’s in there, and what else would be best to take as samples from the wider cellar,’ I said.

‘Also, John,’ George leaned towards me and said in a quiet voice, ‘There may be some need for a little cash to persuade certain parties.’

‘I hope not but I’ll leave that with you, George. We’re partners, remember?’

‘Well, I thought you were a buyer and I was a seller, but in this yes, we have a mutual interest,’ he said. And then laughed that big laugh of his. ‘It will be okay, John. The sale will happen, and it will be wonderful. All will be fine. Hopefully.’

I headed down to the cellar and to the shelves that we’d been told contained Stalin’s collection. My misgivings about the negotiations about us taking bottles home was mixed with excitement that we could finally be face to face with Stalin’s personal favourites.

We huddled by torchlight in the gloom to read the translated Stalin list. It was titled ‘The Collection of IV Stalin with Library’.

The list had a lot more spirits than the general collection. Stalin had broader tastes than the Tsar – and even being able to discern that from the list was a thrill, like we were that much closer to the actual man, instead of the historical figure. Stalin had bought some Yquem, including a 1924 bottle that was listed as 400 ml, which was unusual. There were another fifteen bottles of more standard 1924 Yquem, and then another entry for even more 1924 Yquem, eighteen bottles. But then he had collected eighty bottles of Hennessy Jubilee Cognac. I didn’t know what that was. He had French Chartreuse, whisky and a vodka listed as ‘50 degrees’, which we took to maybe mean 50 per cent proof. There was 1923 Bols gin, from England, and 104 bottles of Chacha brandy, again 50 per cent proof.

As Kevin put it poetically, looking at the list: ‘When old Josef decided to hit the bottle, he didn’t fuck around.’

I went over the list several times, caught up not only in the brands and labels, but also just in the story it told of Stalin, the man. His tastes, his preferences. How he came to like Bols gin over other gins, as the list seemed to suggest. How he got a taste for Chartreuse, if that was true.

Kevin was poking around, examining the bottles themselves, and was intrigued by some other bottles, almost completely hidden under cobwebs, that had mostly lost their labels, although one fragment of label mentioned miel, the French word for honey. They didn’t seem to be on the list so we weren’t sure what they were or where they fitted.

‘Why do you collect honey among a wine and spirits collection?’ Kevin wondered.

‘I’m not sure,’ I said. ‘Is it related to a spirit?’

‘I’ll have to do some homework,’ Kevin said. ‘Also, what are these references on the list to “hardened” wine? What does “hardened” mean?’

‘And while we’re at it,’ I said, laughing, ‘did you notice this little section on the back of the list?’

Kevin came and peered over my shoulder, reading: “King Alexander the Third Collection”. You’re kidding me.’

‘Nicholas the Second’s father,’ I said.

We spent a couple of hours working our way through Stalin’s personal collection, taking photos of a few bottles and wiping cobwebs off many others. Now that we had the list and were able to substantiate the important bottles, I was able to relax, and we just enjoyed being in the presence of history. I couldn’t help but imagine Stalin, in St Petersburg, wandering the racks of these bottles when they were recently arrived from France, labels fresh and wine vibrant inside.

I mentioned this to Kevin who said, ‘Yes, and I want to do the same thing with them in my office in Sydney, just before I sell them. Let’s work out which ones we can take home.’

As soon as we mentioned that we were looking to collect some bottles for authentication, the Georgians started paying much closer attention to our movements.

Grigol immediately said, through Pyotr, that we were not to touch or remove any foreign wines. We nodded and said, yes, Grigol, of course, and then as soon as he drifted upstairs out of the cellar, we began collecting our predetermined list. We put small tags on them, attached carefully to the neck with rubber bands, noting the wine and year, the shelf and number, as most had no labels. One Yquem that we pulled aside had a cork that showed it was from 1870-something, but the final number was obscured. We shone torches at the cork inside the bottle, and could read 187.

We took it anyway. The whole point was to have wine experts, even from Yquem itself – in fact, especially from Yquem if we could organise it – authenticate that it was genuine and which year it was from.

Without our little labels, attached by rubber band, it was hard to know what the bottles were. Removed from the shelf, and therefore the list, each was just a dark bottle filled with liquid. Most didn’t have labels and their corks were often obscured, like that Yquem. Our tags were going to be vital, so we made sure they were securely attached.

We gathered twenty-four bottles, a greatest hits of the collection, you might call it, including an 1847 Yquem and one of Stalin’s personally collected 1924 Yquems.

‘Why the hell not? Let’s see what happens,’ I said.

It was soon after when Revaz, the chief winemaker, came down the stairs into the cellar, followed by George. Revaz’s face was beetroot red, even in the bad light.

Kevin said quietly to me, ‘Let the games begin.’

George did most of the talking on our behalf. Revaz shook his head a lot or waved his arms.

For over an hour, it went to and fro. George was smooth, rarely raising his voice, all reason and explanation, occasionally pointing a hand in our direction as he made a point or indicating the bottles that stood like a silent jury on the table next to our now-cooling LED lights.

Maybe ninety minutes in, George indicated to us that it might be wise to offer the winery executives a gift to ‘smooth things over’. A figure of US$1500 was mentioned, we suggested US$1100 and George played along until we landed on a figure of US$1250. Kevin and I combined our secret stashes and gave George the cash.

I was hopeful that this was the end of it, but of course there was still a problem. Revaz kept saying Tamaz’s name and eventually we all trooped upstairs and George and Revaz disappeared into Tamaz’s office.

We were sitting in the boardroom where we’d had all the interminable meetings a few days before. Pyotr went and got us a beer, which was much needed by this point.

Kevin wrote in his notes, ‘John’s getting edgy.’

And I was. I was pacing now, while sipping my beer. We were so close yet this bunch of suits, running their defunct winery, could kill the entire project on a whim.

Eventually I said, ‘I need some air,’ and walked out to pace the winery’s car park and long-neglected garden. Kevin, Pyotr, Ivane and Nino joined me and it was Kevin who asked Pyotr to fill in the time by taking some photos, of us with each of them, of Kevin and I together, of the winery itself. It hadn’t occurred to me until Kevin produced his camera that this would almost certainly be the last time we’d be at the Savane Number One, on this trip anyway, and so I was pleased to record the moment, even if I was apprehensive about the outcome of the negotiations inside. Nino and Pyotr insisted we pose for photos with handguns in our waistbands, doing our best to look just like Tbilisi-style hard men.

Towards the end of all this, George emerged and updated us on what was happening. It seemed that Tamaz wanted some kind of contract and approval from ‘the authorities’.

We had no idea who ‘the authorities’ were.

Phone calls were made, discussions were held. We went back inside and finished our beers.

An hour later, we were brought back into the negotiations. We agreed that we would leave with ‘six or seven’ bottles, only. Kevin and I immediately took that to mean a dozen.

Revaz was clear that they didn’t want us to take anything of which there were only a few bottles.

I still didn’t want to signal how valuable the entire collection might be, but I also wanted to give us the best chance of flying out with some of the golden bottles.

‘George,’ I said. ‘Just because of its age and condition, the 1847 Yquem is the best possible bottle we could take to impress an auction house.’

He looked down the list and said, ‘But there are only three of them, John. I honestly do not think these men will let you take that one. There is many other Château d’Yquem to choose from, yes? With many more bottles.’

We did have others among our twenty-four bottles, so I decided to let go of the tantalising 1847 for the greater good. I replaced it in the collection with a winery now considered to be one of the iconic first growths, a Château Mouton Rothschild, listed to be from 1874. Our translated list actually had it as a Buton-Rothschild but I was assuming somehow Mouton had become Buton along the way.

In the end, as far as I could tell, Revaz got to keep the $1250 in US currency. I’m not sure Tamaz even knew about the deal.

And to be honest, I didn’t care. We managed to take our dozen bottles out through a side door to Nino’s Mercedes.

‘I wonder if the mafia staff car’s return is linked to the US dollars we just paid them?’ Kevin wondered.

George said he was going to stay behind for a while to do some work but would meet us afterwards for a drink on our final evening together.

‘George,’ I said. ‘Can you please hang on to the other twelve bottles we chose? We’re going to need them, but we’ll have to work out how to get them from you later, at the hotel.’

We drove back and Pyotr joined us in Kevin’s room, where we carefully washed the cobwebs and dirt off the bottles we’d liberated.

We washed them with extreme care, making sure not to dislodge anything important, like the hint of a label, or smudge the handwritten tags that we’d attached. Finally, we packed them into the polystyrene container carried all the way from Australia, hoping for this moment. Then we wrapped bubble wrap around it and put it into a cardboard box, which Kevin expertly taped shut. They were as secure as they could be.