hen you think of the classic folk musician with guitar and harmonica rack, hat, work clothes, and a point of view, you’re imagining Woody Guthrie. The man who told you something you already knew. An iconic American figure who became a legend by singing songs simply.

hen you think of the classic folk musician with guitar and harmonica rack, hat, work clothes, and a point of view, you’re imagining Woody Guthrie. The man who told you something you already knew. An iconic American figure who became a legend by singing songs simply.

Guthrie will always be a symbol of hard times and Depression-era politics, forever representing the twentieth-century folk identity. His genius was to simplify. He tackled the big subjects with an aw-shucks sensibility that proved to be a gift. He wrote, sang, talked, laughed, and borrowed using an American vernacular that expressed the voice of the people—a theme from which he never wavered. Woody’s message was wrapped up in a unique set of beliefs and politics that merged his religious background with a new brand of Americanism layered in modern socialism, with determination to help the poor and the down-and-out.

And yet he was flawed man, with a lifestyle and pattern of bewildering decisions that can be described as selfish and irresponsible, bordering on self-destructive. Some said he had more interest in people in the abstract than the people in his own life. His ramblin’ was renowned, and his commitment to the road would ultimately verify his authenticity as someone who knew the land and its people.

He summed up his ethos as an artist simply: “All you can write is what you see.”

Naturally, his ramblin’ frustrated people close to him, made him a completely unfit father at times, and created a strain on his marriage.

“He could not care less where he spent the night or where he was going the next day,” Mary recalled of her folksinger husband decades later. “He was for the downtrodden, but as far as something for himself or his family, it didn’t make that much difference.”

But Woody would always ramble—in with the dust and out with the wind.

Woody Guthrie illustration for Bound for Glory depicting Okemah, Oklahoma, 1942

Whatever the cause of his deep restlessness, Woody Guthrie knew homelessness as a young man.

Woodrow Wilson Guthrie was born July 14, 1912, just twelve days after his namesake won the Democratic nomination for president. Woody, as he was quickly nicknamed, was the third child of Charley and Nora Guthrie, and at birth seemed destined to enjoy a comfortable middle-class upbringing. Guthrie’s hometown of Okemah, Oklahoma, was a small town on a rocky hill that never quite lived up to its boosters’ aspirations—“The town didn’t amount to much except on a Saturday, when the farm people would come in there to have a trade day,” Woody Guthrie later said. Still, the town was the county seat of Okfuskee County, making it the area’s center of commerce and politics, two topics of great interest to Woody’s father.

As his son’s name suggested, Charley Guthrie was a staunch Democrat. Charley read law as a young man and, with the help of party machine politics, was elected district court clerk for Okfuskee County in 1908, just a year after Oklahoma became a state.

Like the rest of Oklahoma, the county had seen a rush of land settlement after the government opened it up to homesteading in 1889, having previously been reserved for Native American tribes. The famous Oklahoma “Sooners” planted wheat, corn, and—around Woody’s hometown of Okemah—cotton in the parched grassland, trying to make a go of crops in what was, at best, marginal farmland. In the decades after the Sooners arrived, difficult farming conditions led many families into a vicious cycle of debt that caused them to lose their farms and become simple tenants on the land they once owned. Those who had never had land to begin with were faced with low wages that offered little prospect of upward mobility.

These economic factors—all present a generation before the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression—fostered a healthy strain of socialism among Oklahoma’s residents. Drawing off meek-shall-inherit-the-earth Bible scripture and antipathy toward banks and railroads, the Socialist Party was able to pull 15 percent of the presidential vote in Okfuskee County in 1912.

However, no such left-leaning ideas entered the Guthrie home at the time. As the Socialists gained popularity around him, Charley in 1912 published columns in the local newspaper mocking their positions, at times engaging in blatantly racist appeals to the white citizens of Okemah. “Socialism Urges Negro Equality” read one of his headlines, aimed at alarming anyone who considered voting Socialist.

Indeed, Charley Guthrie and his young family seemed entirely removed from the plights of the poor farmers in the area—both economically and physically. Even before running for office, Charley became involved in real estate, and he earned enough money from his dealings to buy the first car in Okemah in 1909. And the Guthries were city folk: Charley ran his business out of an office above a bank downtown, and his growing family lived in town.

“We wasn’t in that class that John Steinbeck called the Okies,” Woody Guthrie later said.

“Papa went to town and made real estate deals with other people, and he brought their money home. Mama could sign a check for any amount, buy every little thing that her eyes like the looks of. [My brother and sister] Roy and Clara could stop off in any store in Okemah and buy new clothes to fit the weather, new things to eat to make you healthy, and Papa was proud because we could all have anything we saw.”

Music was a staple in the Guthrie household: Charley liked square-dancing calls and black labor songs; Nora preferred parlor songs like “Gypsy Davy.” Like many rural adults, the old-timers of the extended Guthrie family had played music as a hobby and as a way to entertain themselves in the days before radio and records, and they still played for each other in their parlors and on their porches. Woody was born into such an environment. He enjoyed his father’s playing and his mother’s singing, and learned the old songs in such a way.

The Guthrie family’s fortune was further improved by World War I, which proved to be a huge boon to Oklahoma. In an effort to boost wheat production, the US government subsidized the price to keep it selling at two dollars a bushel. This led to a new land rush, as war speculators poured into the area, busting up fragile, dusty soil in search of any land that could support the lucrative crop. For Charley Guthrie’s extensive real estate holdings, it meant even better times—and even more impetus to buy Oklahoma farmland on speculation. At the beginning of the 1920s, Charley Guthrie stood as a wealthy man.

It seems impossible to imagine that Woodrow Wilson Guthrie would have become a champion of the workingman had his life continued the way it started for his first eight years. But with the new decade came drastic and devastating changes for the Guthrie family.

With every boom comes a bust, and in the early 1920s the Guthrie family was not immune. When the high wheat prices prompted by the war returned to peacetime prices, tenant farmers working Charley Guthrie’s land began defaulting. This left Charley overextended with the banks and forced him to sell off his holdings at fire-sale prices.

Woody Guthrie later said his father lost $50,000 over the course of 1921 and 1922, and pronounced dramatically: “I’m the only man in this world that’s lost a farm a day in thirty days.”

Meanwhile, the behavior of his mother, which had long been odd and erratic, became something altogether frightening. From early on in Woody’s childhood, Nora had wavered between aloofness and violent outbursts. In 1919, she and Woody’s older sister, Clara, got into a terrible argument, during which Clara accidentally set herself on fire and ultimately died. It devastated the Guthrie family and would be something that Woody never forgot. In the eyes of her neighbors, the incident cast a pall over Nora, but by the mid-1920s it was clear to Woody that his mother was suffering from severe mental illness. At one point, she left her three-year-old daughter, Mary Jo, to wander the streets downtown while she watched a movie, and she was prone to spastic arm movements that haunted young Woody. Then, on June 25, 1927, when Woody was fourteen, his father was severely burned in a fire. Even Charley never got the story straight as to what happened to him, but it was widely believed that Nora had set him alight in a fit of rage. Two days later she was committed to an insane asylum. Woody visited her there once before she died and was buried in an unmarked grave in 1929.

With his father broken financially and his mother mentally, Guthrie was left to find his own way starting at a young age. For a time he took odd jobs and slept where he could as he traveled in the summers to different parts of Oklahoma and Texas, hitchhiking with his harmonica and singing for nickels and dimes.

He said he learned how to play the “French harp”—or harmonica—when he was fifteen or sixteen years old after hearing a black shoeshiner play a blues song on the instrument.

“I was passing a barbershop one day … and there was a big barefooted boy who had his feet turned up toward me, and he was playing the ‘Railroad Blues,’ ” Woody said, telling Alan Lomax about the man who taught him his first harmonica song—following the racist custom of referring to an adult black man as “boy.” “It was on a warm summer day, and he was laying there … and I says, ‘Boy, that’s undoubtedly the lonesomest piece of music I’ve ever run onto in my life. Where in the world did you learn it?’ And he say, ‘I just lay here listening to the railroad whistle, and whatever it say, I say too.’ ”

After that first meeting, Guthrie said, he’d stop by every day and ask the man to play the song, which he never played the same way twice—a folk-music tradition that Guthrie fully employed once he learned to play.

In 1929, Woody moved from Okemah to Pampa, a small town in the panhandle of Texas, where his father had moved following the latest boom. This time it was oil. He took a job as a soda jerk at Shorty Harris’s drugstore and helped his scarred father run a flophouse. It was Prohibition, and Woody capitalized by serving “jake,” pot liquor, and “canned heat” at the purported drugstore, helping the boomtown rats with what ailed them.

But Pampa wouldn’t provide any real stability. When the stock market crashed in October 1929, oil briefly sustained the town. Soon enough, though, economic malaise hit, and his father was put back into poverty. By 1930, Woody was a high school dropout, painting signs, educating himself with frequent trips to the library, and beginning his serious interest in music. He took being poor and near homeless as a matter of fact, but he was resilient. Woody was shaped by the misfortune and unpredictability of his formative years and yet bravely accepted his lot. When his sister Clara died so tragically, he refused to cry. Instead, bearing such pain, he would become the clown, perhaps deflecting serious emotions with humor and lightheartedness. Whatever the case, Woody Guthrie was primarily fending for himself at an early age.

Black Sunday dust storm, Pampa, Texas, 1935

Just as the late 1920s oil boom was ending and the Great Depression was setting in, signs of drought were surfacing on the southern Great Plains. It turned out to be a drought of biblical proportions, one that lasted ten years and turned the place Woody lived into a region known generally as the Dust Bowl.

The dust storms that plagued huge swaths of the Great Plains in the 1930s were a man-made phenomenon caused by bad farming practices on land unsuitable for crop production.

A land that for centuries was a natural sod and grazing area for bison, and later for cattle ranching, was called a “no-man’s-land” for a reason. Many generations of locals knew it wasn’t a place to plant, due to the inconsistent rain and historic periods of drought. But unwisely, it was converted to large wheat farms during the successive land rushes that Guthrie’s family was a small part of.

Land misuse got even worse after Charley Guthrie was forced out of the market. In the 1920s, new, industrial-style farming with mechanized equipment and motorized tractors with doubly effective plows encouraged landowners to buy more and more land in order to plant more and more wheat. Farmers added headlights to their tractors so they could plow ancient sod all night. Easy short-term economic gain motivated “suitcase farmers” and real estate speculators to plant still more wheat and turn over still more land.

Compounding the problem was the government’s decision in the 1920s to enlarge the Homestead Act and encourage more settlement in the southern Great Plains. It was an opportunity for first-time buyers to get a little piece of their own.

There was rampant fraud as land speculators tried to convince families to buy. Historian Ken Burns notes that the real estate hawkers told poorly educated buyers that the weather had permanently changed, that Oklahoma now had a wet climate. They even suggested that the “rain follows the plow, meaning the very act of turning over the soil would bring more rain.”

For a while, in the late ’20s, the rain did fall and goings were good. Small farmers prospered, and corporate farmers prospered even more, all of which resulted in more and more land speculation. But when the rains stopped in 1932, farmers were left with nothing but dry, sandy soil that—on account of the wide destruction of natural grasses that once held it in place—was left to the whims of violent prairie winds.

There were thirty-eight dust storms in 1933. The scariest were the black blizzards that looked like a mountain range one hundred feet high. Burns notes that one storm moved more dirt in twenty-four hours than was moved during the entire excavation of the Panama Canal.

Guthrie was in the middle of it all. He later insisted that while the region known as the Dust Bowl often is associated with Oklahoma, “the blackest, the thickest” dust in the country could be found in the panhandle of Texas. He recalled for Alan Lomax the worst storm to hit Pampa—the Black Sunday storm on Palm Sunday, April 14, 1935.

“We watched the dust storm come up like the Red Sea closing in on the Israeli children,” he said in his characteristic drawl. “It got so black when it came, we all went into the house and all the neighbors congregated. It got so dark you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face.”

People were losing hope. People were scared. Many thought the world was literally coming to an end—the apocalypse brought on by their sinful ways.

As Guthrie watched families stream out of Pampa in search of a new life, he wrote one of his first songs, a ballad that deftly captured the gallows humor of his weary people.

Looking back with today’s perspective, it’s almost unimaginable that such a disastrous convergence of dust and economic depression—two man-made problems—could occur. It was devastating.

Two hundred fifty thousand families fled. Many were victims of circumstance and, to a great extent, a faulty financial system. Woody was then twenty-two years old, and the Dust Bowl would be forever linked to his legend.

It was in Pampa that Guthrie first became what you could call a professional musician, joining up with a group called the Corn Cob Trio and playing hillbilly music for dances and gatherings all over the region. He also freelanced as a musician for other groups, including a cowboy outfit that the local chamber of commerce put together. In 1933, Woody married Mary Jennings, the sister of his bandmate Matt, in the local Catholic church.

Despite the dust and the Depression, it seemed to be a comfortable existence for Woody Guthrie. He was playing music, had a strong social circle, and was close to family. He kept exploring books in the local library that grabbed his interest, took up yoga, and put together his first songbook in 1935; also that year, he and Mary had their first child, Gwen. While some folks had fled to California in search of a better life, they were able to get by on Woody’s work as a sign painter and soda jerk.

But as the decade wore on, Woody’s restlessness was getting to him, and he began looking to get out. At first he made small trips around the area, leaving Mary and their young daughter at home. He started talking about moving to California, which drew groans from family members who’d heard the poor fortunes that had met others when they’d left for that supposed promised land. He made his big move in the spring of 1937—without wife and daughter—when he hopped a freight train to California. After traveling up and down the state a little bit, he settled in Glendale with his aunt.

It was in Glendale that he teamed up with his cousin Jack Guthrie, a musical pairing that set the course for Woody’s career.

Jack Guthrie wanted to be another Gene Autry. Cowboy acts were all the rage in California, and Jack thought that he and Woody made a good combination for a twangy show. However, most radio stations already had their own cowboy performers on air. One exception was the radio station KFVD, which was run by a populist named J. Frank Burke. KFVD was largely a political radio station, championing various liberal causes affecting California.

The two Guthrie cousins—content to sing the old songs of Oklahoma—were meant to be a break from political programming. But for Woody, the opposite was true: the station turned him political.

Jack and Woody were good enough to gain listeners, but they didn’t make a lot of money. Like Woody, Jack had a wife and kids. Unlike Woody, he worried about providing for them, and after a few months on KFVD, he quit the program for more gainful work. Woody stayed on, and brought on a sidekick: Maxine Crissman, a.k.a. Lefty Lou.

Woody Guthrie and Lefty Lou with sign for show on KFVD Radio in Los Angeles, circa 1937

The show Here Comes Woody and Lefty Lou was Woody’s first exposure to wide popularity. The next two years proved beyond a doubt that Woody Guthrie had the charisma that could connect him to an audience. With Lefty Lou, he first started performing his own songs on the radio, many of which resonated with the listeners. Among them was the song “Oklahoma Hills,” a tune that endures as one of Woody’s most popular.

So many listeners wrote in asking for his lyrics that he began mimeographing songbooks in the KFVD office to sell to them.

Guthrie was apolitical when he arrived in Los Angeles, but working at the populist KFVD made exposure to leftist politics nearly inevitable; the ideology’s focus on the working class was instantly attractive to him, and he quickly emerged as a political thinker in Los Angeles.

A Dust Bowl migrant himself, it didn’t take long for him to see the deplorable way dispossessed farmers from the Great Plains were being treated. Fruit-farm owners had distributed handbills all across the Dust Bowl telling folks that good jobs and high wages awaited them in California, but that turned out to be just part of an effort to drive down labor costs for fruit pickers.

“They’d heard about the land of California, where you sleep outdoors, and you work all day in the big fruit orchards and make enough to live on and get by on and live decent on and work hard and work honest,” Guthrie recalled. “And, according to these handbills passed out, you’re supposed to have a wonderful chance to succeed in California.”

When the flood of migrants came in response, many ended up as vagrants, which brought on the wrath of local authorities, who saw them as a scourge on their communities. It was common practice for state troopers to arrest people for being out of work, and then force them to work for free picking the fields.

“When you came to that country, they found different ways to put that [vagrancy] charge on you to get you working for free, either in a pea patch or a garden or hay or something, and so you were always working and you weren’t getting nothing out of it,” Guthrie recalled.

His song “Do Re Mi” summed up the raw deal he saw his people getting in California:

Oh, if you ain’t got the do re mi, folks, you ain’t got the do re mi,

Why, you better go back to beautiful Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas,

Georgia, Tennessee.

As biographer Ed Cray notes, the song is a direct rebuttal of singer Jimmie Rodgers’s assertion that the water of California tasted “like cherry wine.”

KFVD’s station manager, Burke, saw Guthrie as a strong new voice in the progressive causes he championed—among them, rights for migrant farmers. Along with keeping him on the air—giving him a platform to play his new ballads—Burke hired Woody on as a “hobo correspondent” for his leftist newspaper, the Light. Guthrie spent time on the railcars and under the bridges to report on the economic plight afflicting his people. He also visited the labor camps set up by the orchard owners, where workers lived in squalor as they barely scraped by with their earnings from long days of manual labor.

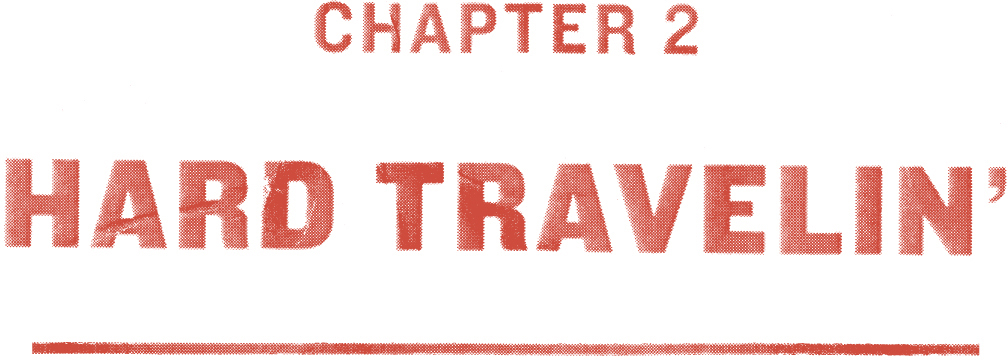

Woody Guthrie and Fred Ross, manager of Shafter Farm Workers Community, California, 1941

Guthrie also visited the camps the Farm Security Administration established to give sanitary shelter to the migrant farmers—the same camps that provided John Steinbeck with his material for The Grapes of Wrath. Steinbeck and Guthrie met each other at this time, becoming fast admirers of each other’s work.

The migrant worker camps—established by the Roosevelt administration to ease the plight of the Dust Bowl refugees—served as an important prologue to Guthrie’s experience in the Pacific Northwest. Namely, they suggested to him that federal government intervention could improve the lot of the common man. The FSA built fifteen sanitary camps and, in the view of many, offered a dignity that had been lost in the depth of the Depression. As historian Richard Nate notes, Steinbeck’s character Tom Joad mirrors Guthrie’s own view on how the people could be helped with New Deal policies:

I been thinkin’ how it was in that gov’ment camp, how our folks took care a theirselves, an’ if they was a fight they fixed it theirself; an’ they wasn’t no cops wagglin’ their guns, but they was better order than them cops ever give. I been a-wonderin’ why we can’t do that all over.

The Columbia River projects may have been the closest New Dealers ever got to “doing that all over,” and Guthrie proved very excited by that prospect.

A Farm Security Administration migrant camp in El Rio, California, 1941

Burke also introduced Guthrie to several avowed communists who quickly became close collaborators. The two most important in Woody’s life were Ed Robbin and Will Geer. Geer was an actor working under Orson Welles in a federal theater production—best known later as the grandfather in the TV series The Waltons. Geer and Guthrie traveled to migrant camps together. In fact, it was Geer who first exposed Guthrie to the plight of migrant farmers. Meanwhile, Robbin hosted a political radio show on KFVD and was the California correspondent for the Communist Party newspaper, the People’s Daily World. Robbin invited Woody to his first Communist Party event in 1939, a rally at which Woody sang and was a hit with the crowd. He also helped Woody get a column with the People’s Daily World, called Woody Sez. The column—which typically ran about five paragraphs and sometimes included small drawings—displayed how fully Guthrie had developed his folksy take on politics in his few short years in Los Angeles. In a typical column published in 1939, Guthrie rewrote the Pledge of Allegiance to read: “We pledge allegiance to our flag … and to Wall Street for which it stands … one dollar, ungettable.”

Guthrie visiting Shafter’s camp in California

Guthrie was certainly sympathetic to many communistic causes, especially as far as they would empower the poor workers in California. However, he was never a party man, and he always held on to a heavy dose of his Oklahoma Christianity when interpreting the world around him. Biographer Ed Cray described his patchwork of ideas and moral beliefs as “Christian socialism.”

In his journal, Woody summed up his politics this way: “When there shall be no want among you, because you’ll own everything in common. When the rich will give their goods into the poor. I believe this way. This is the Christian way and it is already on a big part of the earth and it will come. To own everything in common. That’s what the Bible says. Common means all of us. This is old ‘Commonism.’ ”

But not being a party man didn’t mean Guthrie couldn’t be stubborn on some points.

Illustration from the Woody Sez series by Woody Guthrie, 1939

In a display of how deeply into politics Guthrie was during his two years in Los Angeles, he got caught up in an ideological fight that broke out on the American left in 1939 when the Soviet Union reached a peace pact with Nazi Germany. Many leftists who saw communism as a strong bulwark against fascism were repulsed by the pact and fled the party. Guthrie stuck with the party, writing songs that argued that anything that kept Europe out of war was good for the common man, since he bore the brunt of armed conflict.

That viewpoint didn’t sit right with Burke, and Guthrie lost his show, leaving him out of work in Los Angeles. But Geer by that time had moved to New York, and gave Guthrie an open invitation. Woody was soon off to New York.

So long, it’s been good to know yuh.

“Ballad of the Great Grand Coulee” (Grand Coulee Dam) Words and Music by Woody Guthrie. WGP/TRO – © 1958, 1963, 1976 (copyrights renewed) Woody Guthrie Publications, Inc. & Ludlow Music, Inc., New York, NY (administered by Ludlow Music, Inc.)