decade earlier, in the 1930s, America was trying to find its voice again.

decade earlier, in the 1930s, America was trying to find its voice again.

In 1933, at the peak of national bankruptcy and four years after the stock market crash brought the economy to its knees, 12.8 million people were out of work—one-fourth of the entire working population. Gross domestic product nearly halved as factories and farms alike ground to a halt in the wake of Wall Street’s devastation. The economic depression caused a crisis of authority in American society. Great financial institutions that had generated unimaginable wealth for certain segments of the population were now shown to be deeply flawed, and the government that was supposedly for and by the people seemed to have little power to help the suffering populace. The Great Depression was on.

From these ashes grew a new belief that the American economy could move forward only by relying on its underlying strength: the workingman.

To understand why Woody Guthrie was hired by the BPA in 1941, it is important to grasp the way in which folk artists like him had come to embody for much of the society both a look into the past and a path forward. By using the simple principles of common folks, people believed, America could reinvent itself as a populist utopia that was no longer beholden to private interests.

This was not an entirely organic phenomenon. A broad range of the American left—from New Deal Democrats to the Communist Party—sought to incorporate folk art into its vision for a reformed America in the 1930s. But while these organizations were embracing folk culture for their own purposes, the combined effect was a cultural renaissance. Among the work of this era stand some of the finest examples of Americana—not least of which are Guthrie’s Columbia River songs.*

Franklin D. Roosevelt called them “the forgotten man.” In a radio address in 1932 from the New York governor’s mansion in Albany, FDR said that America’s leaders had ignored the everyday worker in the economy. Instead, they’d put their trust in the “more spectacular” sections of the economy—namely banking.

“These unhappy times call for the building of plans that rest upon the forgotten, the unorganized but the indispensable units of economic power, for plans … that build from the bottom up and not from the top down, that put their faith once more in the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid,” Roosevelt said.

When he was elected president nine months later, FDR didn’t just remember the once-forgotten workingman. He made him the center of policies that sought to use workers—the farmer and the laborer—to claw the nation out of the depths of the Great Depression. In his first one hundred days in office, his government got fifteen major bills through Congress, affecting everything from banking—nine thousand banks had failed—to agriculture, a sector of the economy that was seeing an average of twenty thousand farm foreclosures a month. Congress approved $500 million to shore up state welfare systems and launch public projects intended to put Americans to work.

In addition to a financial recovery, Roosevelt believed the hard-hit nation was in need of a psychological recovery as well. His reassuring “fireside chat” radio programs sought to soothe the fears of Americans enduring the worst domestic crisis since the Civil War. In the same vein, his government enacted policies that emphasized America’s cultural wealth even as the economy struggled. In the words of historian Richard Nate, the Roosevelt administration explicitly attempted to “raise the people’s self-confidence in a time of crisis.” They did this in part by putting artists on the government dole who expressed the strength of the American character through telling the history of the common folk.

Overseen by the Treasury Department, the Public Works of Art Project hired thirty-six hundred artists to paint murals—many of which are still on display—in new public buildings in all forty-eight states. This initial program was disbanded in 1935 and replaced by an even more ambitious federal arts effort included in the New Deal’s flagship Works Progress Administration.

The arts section of the WPA was called Federal Project No. 1, or Federal One. In the first year of its existence, the WPA allocated it $27 million—a significant amount of money but a small portion of the WPA’s overall $4 billion budget.

There was some debate at the creation of Federal One about whether its main purpose was to simply give work to out-of-work artists or to explicitly advocate art that promoted an American version of progressive government. The latter was the assured result with the appointment of Holger Cahill as director of the Federal Art Project, part of Federal One. Cahill, a bit of a charlatan who greatly exaggerated his educational background, was a true crusader against stodgy classic art on the American continent. It was his belief that the best art is that which is authentic to the place around it. As such, his objective was fostering new works that aimed to reflect the character of the worker’s role in reshaping the American identity.

WPA poster created by the Federal Art Project

“Early on, he drew a connection between folk art, the art of everyday life, and the Federal Art Project,” art historian Susan Noyes Platt wrote about Cahill’s approach. She said Cahill shared the principles of museum director John Cotton Dana, who wrote that to study American art “is not to read works on esthetics or on the history of art production.… It is not to parade … through the art galleries of Europe.” Rather, it was “to learn to know and feel this beauty in every-day objects which have been produced in America.”

Cahill believed that by fostering American art for Americans, the government could help give voice to those who had once not had a platform in the United States and make the humanities more accessible to the masses.

“No great art has come out of schools and colleges of art, but out of centers like this,” Cahill said in 1938 when dedicating an art center in Harlem that hosted black artists. “We are not particularly interested in developing what is known as art appreciation. We are interested in raising a generation … sensitive to their visual environment and capable of helping to improve it.”

Cahill’s anti-academic rhetoric, however heavy-handed, illustrated the convergence of public policy and art theory in the 1930s. The New Deal arts ethos could be summed up as one that celebrated the common man and favored dignity over destitution. A prime example of the government’s efforts is found in the Farm Security Administration’s photojournalism program. Photographers Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Arthur Rothstein, and others captured images that came to represent both the hardships of the times and the resilience of the people living through them. They sought to not just inform the public about the state of America but to move them.

Dorothea Lange in the field, 1936

Many left-wing artists were stimulated by a newfound patriotism. Once shown the scenes and stories of their own country, it’s as if they discovered their own culture—native and indigenous art forms and folklore never before broadcast to a wide audience.

John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and other defining masterpieces of the decade, such as Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and Carl Sandburg’s book-length poem The People, Yes, also reflected the cultural sentiment of the times.

In 1935, the Communist Party made a concerted effort to use folk art as a way to Americanize and make itself less foreign. Long a simple facsimile of European communism, the party in America came to understand that an atheist, militant movement would never gain a wide following in the United States. To soften its image and broaden its membership, in the mid-1930s, it began sponsoring a movement that came to be known collectively as the Popular Front.

As defined by historian Michael Kazin, the Popular Front was a “vigorously democratic and multiracial movement in the arts and daily life that was sponsored but not controlled by the Communist Party.” The party sought to become less sectarian and to build coalitions with other like-minded American leftist organizations, ones that were antifascist and proworker. Suddenly, the Communist Party in the United States stopped deriding FDR and the New Deal and became aligned with its goals of improving conditions for the American worker in the United States.

The party began espousing slogans such as “Communism is twentieth-century Americanism” and embracing art forms that it once despised—namely, popular film. With this softened image, it made successful entreaties to Hollywood, which soon flocked to the Popular Front. Americans who believed in everything from women’s rights to racial equality were suddenly attracted to the broad coalition the Popular Front was building under the banner of the traditional American ideals of hard work and strong community. It’s important to be clear that not all artists who were labeled “Popular Front” were communists. On the contrary, many progressive thinkers shared a cultural path with the Popular Front unified under the ideas of reform, the civil rights of all Americans, and, most importantly, taking a stand against rising fascism in Europe.

Historian Leonard Quart noted that the Popular Front seemed the “perfect embodiment of left-wing ideals” for Hollywood liberals. “For the first time … a large number of artists and intellectuals had found that through the Popular Front they could simultaneously belong to a ‘radical’ mass movement and be good Americans.” Historians agree that the rise of the Popular Front heavily influenced American art in the 1930s, as it brought artists from a wide swath of American life together in a shared mission of creating works that celebrated the working class. It also helped the Communist Party for a time. During the Popular Front movement, the party saw its highest membership in America ever, reaching one hundred thousand. But the communists seemed to almost be a victim of their own success, as the music created by Popular Front artists was entirely incorporated into American culture—divorced from its intended communistic overtones (if any existed to begin with). For example, Popular Front member Earl Robinson’s “Ballad for Americans” was performed at the Republican National Convention in 1940.

Just how closely these “fellow travelers” hewed to party-line Communism in the 1930s would eventually be the subject of congressional hearings. But at the time, it was not a pressing concern and there was fluid movement of personnel between the Popular Front and FDR’s New Deal arts programs—both of which emphasized the same vague idea of exalting the common man by way of advancing a political agenda that promoted a new social democracy.

Whether you call it public relations or propaganda, much of the art created under Federal One and other government arts programs of the time often used the folk aesthetic lauded by Cahill to expressly promote federal programs—including public power and dams.

The ultimate precursor to Woody Guthrie’s entry into the Pacific Northwest was a play called Power. In 1937, the WPA’s Federal Theatre Project debuted the play, which amounted to a folk-themed stage production that sought to get the public behind the idea of government-owned power by telling the story of the Tennessee Valley Authority. It was part of the Federal Theatre Project’s Living Newspaper series, which put the current affairs of the nation on the stage through dramatic productions.

With the debate just ramping up in the Pacific Northwest, public-power advocates staged the play at the Metropolitan Theatre in downtown Seattle. Their partisans filled the seats of the playhouse, and publicly owned Seattle City Light donated large transformers to the theater to help set the stage. It was widely derided by conservatives for its folky tone and overbearing message. “That Old Debbil, the Power Trust, is the villain and the TVA is the hero in as fine a piece of overdone propaganda as ever trod the boards,” the Seattle Daily Times sniffed when the production hit the theater. “The play has the subtlety of a sledgehammer and the restraint of a groundswell.”

Poster of Seattle’s production of Power, 1939

The Roosevelt administration was unapologetic for its use of federal dollars to promote its policies. In defending Power, an administrator gave a clear look at the sort of populist righteousness New Deal Democrats carried.

“People will say it’s propaganda,” WPA director Harry Hopkins told the cast following the first production of Power. “Well, I say what of it? If it’s propaganda to educate the consumer who’s paying for power, it’s about time someone had some propaganda for him. The big power companies have spent millions on propaganda for the utilities. It’s about time that the consumer had a mouthpiece. I say more plays like Power and more power to you.”

Notable in the production of Power was its incorporation of folk music commissioned specifically for the play.

Years before the BPA hired Woody Guthrie to write songs about the Columbia River, the WPA commissioned a folksinger named Jean Thomas to write a song called the “Ballad of the TVA.” Thomas is best known as the founder of the American Folk Song Festival, one of the first attempts in the country to formalize the “singin’ gatherings” that were common in her home state of Kentucky. Thomas lacked the gift of subtlety that Guthrie would employ in his pro-public-power songs, but that fact makes her ode to the TVA a perfect example of the high-rhetoric optimism with which New Dealers hoped to infect the public, and the way they wrapped it in folksy packaging. At the end of Power, the actors took the stage, locked arms, and rejoiced, singing the TVA song:

All up and down the valley, they heard the glad alarm;

The Government means business, it’s working like a charm.

Oh, see them boys a-comin’, their Government they trust,

Just hear their hammers ringin’, they’ll build that dam or bust!

If the Tennessee Valley Authority was the test case in FDR’s grand new public-works concept, then the Columbia Basin proved to be the next case. It showed what the government was willing to do to remake America, but on a much grander scale.

What New Dealers had in mind for the Columbia Basin would take the sort of planned farming communities seen in California to a scale that challenged credulity. Their solution to the Dust Bowl crisis and the thousands of displaced migrant families was a land reclamation project in the Pacific Northwest with newly irrigated acreage the size of Delaware dedicated to family farms. It was dubbed a “promised land,” and that was just the start of the lofty rhetoric to come from the idea of harnessing the immense potential of a wild river.

New Dealers knew that a big dream like this wouldn’t succeed without high-minded optimism and the support of the public, but the idea gained significant traction because Woody Guthrie and many others believed in it. For Woody, it was “what man could do” for his people.

The result was the Grand Coulee Dam, although it came with a high toll in human and environmental costs.

Over the course of a weekend in June 1940, Native Americans from across the Pacific Northwest gathered in Kettle Falls, Washington, for a three-day “Ceremony of Tears.”

For thousands of years, the tribes of the Pacific Northwest were sustained by the salmon runs of the Columbia River. Salmon are anadromous fish, meaning that they spend most of their lives in saltwater but swim, or “run,” up freshwater streams to lay eggs and die. With its wide mouth and passable waterfalls, the Columbia River was a vital highway between the Pacific Ocean and freshwater spawning streams from Oregon to northern British Columbia. Kettle Falls, located on the river just thirty miles from the Canadian border, was long a symbol to native peoples of the great bounty provided by the Columbia. They called the area “Roaring Waters” or “Keep Sounding Water,” and as many as fourteen tribes traditionally congregated there during salmon runs in order to fish and trade. It was an ideal spot for fishing, as the eponymous waterfalls blocked the salmon’s passage up the river, causing a mighty traffic jam of fish. There were so many, legend said a man could walk across the water on the backs of the writhing spawners.

But that June, tribal members knew that the falls, and the salmon, would soon be gone forever. The Grand Coulee Dam—the massive structure that Woody Guthrie would call the “mightiest thing man has ever done”—would soon be completed, backing up the river and creating a lake behind the dam, submerging the falls under ninety feet of water. Also submerged would be tracts of the Colville and Spokane Indian Reservations, requiring the relocation of more than twelve hundred graves. The salmon, meanwhile, already greatly impeded by the Bonneville Dam downriver, would be entirely cut off from a huge swath of their natural spawning ground. Within a few short weeks, the land that had sustained these people for thousands of years would be utterly transformed by an audacious feat of engineering that still stands today as one of the most ambitious—and, some argue, arrogant—in human history.

By today’s thinking, it can be difficult to understand why a folksinger like Woody Guthrie, who proved willing to walk away from good money based on principles before, so vociferously endorsed a project like the Grand Coulee Dam. It killed salmon, took away tribal land, and powered war industries—all factors well understood by the time Guthrie arrived.

While some people have castigated Guthrie for his support of the dams, others have tried to apologize for him by suggesting he was naive and didn’t understand what he was being asked to endorse. Neither point of view gets to the more complicated truth.

Guthrie was deeply affected by the collapse of the Oklahoma and Texas economies due to prolonged drought, and the limited options open to the dispossessed farmers who migrated to California. He was also impressed by the efforts of the federal government to help migrant workers in Southern California—via the farm labor camps where he performed and Weedpatch Camp, which Steinbeck featured in The Grapes of Wrath.

The Grand Coulee dam backs up water forming Lake Roosevelt; diverted water is pumped uphill creating Banks Lake, a reservoir for the Columbia Basin irrigation project

To Woody Guthrie, the Dust Bowl balladeer, the dams were the answer to the ills of his time and the path forward for his people.

This fantastical and dramatic undertaking in the middle of nowhere began in earnest in 1933, but the story of Grand Coulee really begins thousands of years ago during the last ice age.

At that time, as massive glaciers began to melt on the American continent, cataclysmic floods repeatedly swept through an area stretching from present-day Missoula, Montana, to the Pacific Ocean. The floods were biblical in size—geologist J Harlen Bretz theorized that the flows contained five hundred cubic miles of water, ran six hundred feet deep, and lasted a month at a time. In the wake of the mammoth flows were huge dry canyons and channels called “coulees,” carved by the huge volumes of water.

But even before the geology of the region was well understood, the idea of using dry river valleys and the natural tilt of the land for irrigation was percolating. Central Washington boosters understood that if you could just divert some of the Columbia River into the ancient Grand Coulee riverbed, gravity would turn it into a great irrigation ditch, stretching from the site of the current Grand Coulee Dam all the way to Pasco—hundreds of parched miles to the south. On account of the steep rock walls that line both sides of the Grand Coulee, the canyon could be turned into a giant reservoir to regulate the flow of the water. Making the idea all the more attractive was the fact that the farmland in the Columbia Basin—made up of rich loess soil deposited by ancient volcanoes—proved good for many early homesteaders, as long as it rained. If farmers could ensure that they got enough water every year, high yields were all but guaranteed. In this vision, the electricity produced by a dam was secondary. It would power the water pumps needed to haul water out of the Columbia and into the Grand Coulee, and any surplus could be sold to pay for the construction of the rest of the irrigation system.

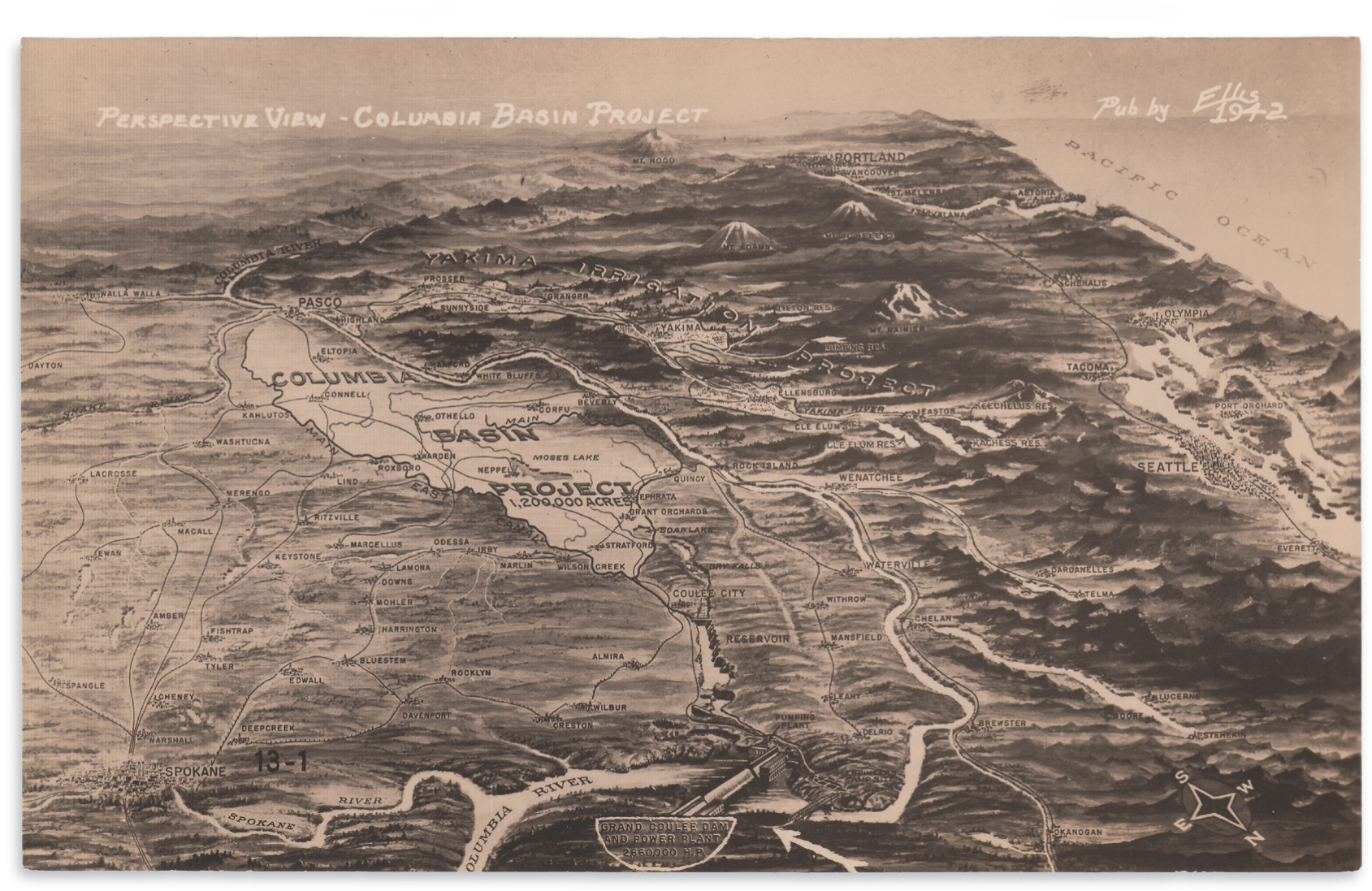

A postcard illustration of the Columbia River Basin irrigation project

This crazy irrigation scheme was first dreamed up by some small-town geniuses in Ephrata, Washington. Over lunch on a hot summer day in July 1918, a lawyer named Billy Clapp presented the idea to the visiting publisher of the Wenatchee Daily World, Rufus Woods. Woods and Clapp were part of an informal consortium of Central Washington businessmen intent on turning their region into an economic powerhouse, instead of the desolate stopover between Spokane and Seattle that it then was.

With the seed of a dam planted in Woods’s brain, the idea now had a publishing platform from which to spread. Woods used his newspaper to highlight engineering studies that showed the Columbia River had 3.5 million horsepower of untapped energy and that the Columbia Basin contained 1.8 million acres of irrigable land. As historian Richard White notes, Woods presented the news not as dry engineering, but as a “melodrama” that pitted good-hearted workers in Central Washington against big moneyed interests back East.

From Woods’s boosterism sprang a grassroots movement that saw farmers, industrial dreamers, and local advocates pressing for the Columbia to be harnessed for their benefit.

Over the 1920s, the idea simmered. Then in 1925 a US senator from Washington managed to get the Army Corps of Engineers to conduct a major study on the mechanics of a Columbia Basin reclamation project. While plan boosters focused on the irrigation potential for the dam project, the Corps focused in on the immense amount of power a dam would create. And it deemed such a project feasible. However, the report also noted that there was a big problem with damming the Columbia: not nearly enough people and industry in the region to justify all that electricity. The Corps concluded that it would sign off on dams built by private or municipal utilities along the river, but the federal government wouldn’t be involved in construction.

Richard White suggests that had the 1930s been a normal decade, that report would have put an end to the idea of a dam at the mouth of the Grand Coulee. But the ’30s were a time of upheaval, a decade of social transformation caused by economic destruction. With a quarter of adults out of work and public distrust of private interests at a peak, a massive public-works project along the Columbia River was precisely the kind of project Franklin D. Roosevelt had talked up during his run for president in 1932. Upon taking office in 1933, FDR almost immediately pushed legislation through Congress that approved the construction for the cornerstone of the Columbia River projects: the Grand Coulee Dam.

As with any major piece of policy, advocates for the dam didn’t necessarily see eye to eye on specifics. To cite just one example, Rufus Woods was opposed to public ownership of electricity while his pro-dam ally, the Washington State Grange, was the driving force behind public utility districts.

But when the federal government took up the project in 1933, a clear vision for what the project would achieve emerged that was every bit as utopian as FDR’s rhetoric on the campaign trail. With its alphabet soup of newly minted government agencies, the Roosevelt administration foresaw creating a new kind of agrarian society that, through engineering and government oversight, would be free of the turmoil that had plagued farmers since biblical times. Poor families with failing farms in the drought-stricken Midwest would have the opportunity to own newly irrigated land for cheap, the opportunity to start anew. Drought would be eliminated through irrigation from the river; overburdensome labor would be lightened by electricity; even the placement of townsites would be improved through careful planning. This was the “planned promised land,” a term coined by historian Richard Lowitt to describe the New Dealers’ vision.

Congress authorized a total of 2.5 million acres for the Columbia Basin Project. The number of acres projected to be irrigated by the project at its outset was 1.1 million.

Unlocking this much land for settlement inevitably led many writers at the time to hark back to the original expansion into the western frontier, which defined nineteenth-century America. Just as landless settlers had been able to forge a self-determined life through homesteading across the West via the Oregon Trail, so the newly landless Dust Bowl refugees would be able to do as well.

“I have heard these men talking about remote valleys no one has ever explored and secluded ranges no one has ever penetrated.… It is a frontier, and some day the country will spill the surplus population over in it,” reporter Richard Neuberger wrote in his 1938 book, Our Promised Land.

The first step of conquering this frontier was building the Grand Coulee Dam. On November 1, 1933, the dam was named by the federal administrator of public works as Public Works Project No. 9. It would span 4,173 feet at the crest and raise the Columbia River 550 feet above its lowest bedrock. The reservoir it created would run 150 miles, all the way to the Canadian border.

Night scene of the Grand Coulee Dam under construction, 1939

When construction on the giant dam began, it quickly captured the imagination of a nation. At a time when diversions from everyday life were a welcome respite, the story of “The Biggest Thing on Earth” was both a curiosity and a symbol of modern progress. Americans were infatuated with the movies, and Saturday matinees were standard entertainment in every town in the ’30s. Typically a set of films was shown, including a feature, some shorts, a newsreel on current events, and public service announcements. Among items of national interest, updates of Grand Coulee construction were regularly screened. Thus most every American, no matter where they lived, knew about the big project on the Columbia River in the middle of Washington State. And with the publicity came tourism. Soon curiosity seekers started making the trip to the desolate spot where the river bends to see for themselves the history in the making.

Hysterical map of Grand Coulee by Lindgren Bros, 1935

The small towns of Grand Coulee, Mason, and Electric City formed, and soon a small tourist economy developed, complete with postcards, tour brochures, comical maps called “hysterical maps,” and other promotional items. The Wenatchee Daily World was a constant booster of the project, but the more conservative Spokane Statesmen Review also ran copy of the goings-on in the desert. Something was happening, and all the hype was suggesting it was something big.

B Street, Grand Coulee, 1940

The Green Hut Cafe, perched next to the rising dam, was built to accommodate the tourists, the engineers, and their guests. The workers building the dam, meanwhile, could most likely be found during their off hours on nearby B Street, two blocks full of boomtown businesses catering to men, particularly bars and brothels. These establishments were open twenty-four hours year-round, in keeping with the around-the-clock schedules of work on the dam. The dirt stretch was hot, dusty, and dry in the summer and cold, muddy, and wet in the winter.

The Green Hut Cafe and Curio Shop, 1940s

As large as the dam project was, though, planners believed it would soon be overshadowed by the even more ambitious irrigation project it was to feed.

Roosevelt envisioned an orderly relocation of farmers from across the country who would work small plots of land in the Columbia Basin. For every new acre of land planted, the administration hoped to take five acres of bad farmland prone to erosion out of production, thereby preventing another Dust Bowl. Conservative critics of the president thought his vision for the Columbia Basin verged dangerously toward a totalitarian agriculture program. Still, New Dealers were intent on using the power of the federal government to ensure that poor small farmers looking to start over would benefit.

Congress limited the size of farms irrigated by the Grand Coulee project to forty acres per farmer, and eighty acres for a married couple. To discourage speculators, aggressive controls were put on how much private landowners could charge for land in the Columbia Basin. Congress even gave the federal government the power to establish townsites there. Roosevelt saw the project as an opportunity not only to improve agriculture in the United States, but to actually encourage the development of an agrarian society over the urban one that would ultimately prevail in twentieth-century America.

“We will do everything in our power to encourage the building up of the smaller communities in the United States,” Roosevelt said during a 1937 speech about the Columbia River projects. “Today many people are beginning to realize that there is inherent weakness in cities … and inherent strength in a wider geographical distribution of population.”

These policies never came to full fruition. As such, it is difficult to understand how Roosevelt’s vision would have played out in the Pacific Northwest. But suffice to say that under FDR, the federal government was intent on taking deliberate steps toward reshaping America as a carefully planned agrarian society. In the Northwest, that meant the federal government had established the infrastructure to deliver cheap irrigation to a network of small family-owned farms, what one New Dealer said would be a “modern rural community of a million people.”

The “planned promised land” was all planned out.

Meanwhile, the power FDR had spoken of the federal government harnessing from the Columbia River was finally coming online. It was only five years prior that Roosevelt had visited nearby Portland and asserted that private utilities were overcharging customers and under-serving the Pacific Northwest.

Appropriately, Roosevelt himself hit the switch at the Bonneville Dam that started the dam’s two hydroelectric generators whirring on September 28, 1937. He reiterated the populist thrust behind the project, noting not only the dam’s power production but also the new system of locks that would allow large barges to ply the Columbia for the first time. “Truly,” he said, “in the construction of this dam we have had our eyes on the future of the nation. Its costs will be returned to the people of the United States many times over in the improvement of navigation and transportation, the cheapening of electric power, and the distribution of this power to hundreds of small communities within a great radius.”

With electricity flowing, the Bonneville Power Administration began building its transmission grid—drawing unsuccessful lawsuits from private utility companies that still hoped to keep the federal government out of the industry. And public utility districts, which connected customers to the BPA grid, were flourishing: between 1937 and 1941 alone, thirty-two PUDs were created in the Columbia Basin, adding to an already robust roster of publicly owned utilities in the region.

As promised, the system delivered drastically decreased power rates. BPA contracts between publicly owned utilities—be they municipal systems or PUDs—were reducing rates by an average of 50 percent. BPA administrator J. D. Ross expressly advocated for PUDs during local elections, and the BPA encouraged the creation of more PUDs by setting a policy of giving preference to public utilities over private and industrial ones. Roosevelt’s Rural Electrification Administration provided these new utilities with cheap federally backed loans to allow them to build the infrastructure needed to tie into the Bonneville system.

The first community to receive power from the Bonneville Dam was Cascade Locks, Oregon. With a 3.4-mile transmission line between the dam and the town’s municipal power system, the first public power started flowing in the Pacific Northwest in 1938.

The BPA wasn’t just responsible for providing public power; it also was supposed to market it—which amounted to government-funded campaigns convincing people to use more electricity. Because of cheap power, the BPA said in advertisements run in newspapers in the region, residents could embrace a modern lifestyle, with everything from electric coffeemakers to radios. “Forest Grove homes now can replace the old wood stove with a new electric range and their power bills won’t be a penny higher than they were last year,” read one advertisement for that Oregon community.

BPA poster advertising the consumer benefits of hydroelectricity, circa 1940

But while local customers were pleased, eastern observers remained dubious of the benefits of Roosevelt’s shiny new public power program. They saw millions of tax dollars pouring into the projects for scant national gain. The dams at Bonneville and Grand Coulee were commonly referred to as “white elephants” and “boondoggles”—the epitome of New Deal excess. Those attacks ceased, however, as the prospect of war dawned on the nation.

As Hitler and the Japanese grew more bellicose in their actions, the United States began taking steps to supply its allies with war materials (and then, of course, troops). Back at Grand Coulee, as one observer put it, the dam itself was essentially “drafted” into the war just as it came of age.

Dam contractors rushed to complete the first power station there, and power began running off the dam in January 1941, two years ahead of schedule. By 1942, the dam was sating the hunger of aluminum plants across the Northwest. The aluminum was sent to shipyards, and to Boeing to produce planes like its “Flying Fortress,” the B-17 bomber. Over the course of the war, Boeing produced 6,981 of the bombers in its Seattle plant. According to historian William Joe Simonds, in 1940 the Northwest had no aluminum-production capacity, but by the end of the war, it was producing a third of the nation’s supply, nearly all on Grand Coulee juice.

In 1940, the BPA completed a 234-mile transmission line between the Bonneville and Grand Coulee Dams, creating the backbone to the system’s grid, which still stands today. With power now running off both dams, the Columbia River had been harnessed. It was considered to be “the greatest system for hydroelectric power in the world.”

BPA poster emphasizing the agency’s war contribution

Cheap public rates, a new dawn for farming, industrial might with newly navigable waters, flood control, and ultimately the power needed to win a war—these were the great promises and future benefits that the Columbia River projects carried. But at the time of Woody Guthrie’s trip to the area, the great costs were also understood: millions spent and billions yet to be spent on developing the irrigation system and increased power production; nearly half of all Columbia River spawning habitat cut off from salmon—more than one thousand miles of river and streams; and Native Americans losing their homes and traditional fishing grounds.

Still, for Woody, seen through the lens of war and Great Depression hardship, the benefits to the people were hard to pass up. The dam project was his idea of democratic socialism realized. It was what man could do to remake America and help people.

US Senator Homer Bone, Democrat of Washington, said as much when he addressed the tribal members gathered in 1940 for the Ceremony of Tears.

“We can build more airplanes and tanks and can train more pilots for national defense than any other nation or combination of nations, and the quicker we do it, the better. We know now that the only thing in this world that Hitler will respect is more force than he controls,” Bone said. “The Indians have fished here for thousands of years. They love this spot above all others on their reservation because it is a source both of food and beauty. We should see to it that the electricity which the great dam at Grand Coulee produces shall be delivered to all the people without profit, so that the Indians of future generations, as well as the white men, will find the change made here a great benefit to the people.”

*Most all of the creative work produced by artists in the progressive communities of the 1930s embracing populism and the “people’s idioms” are today considered classic examples of Americana. John Steinbeck, Charlie Chaplin, Lead Belly, Carl Sandburg, Orson Welles, Aaron Copland, and Frank Capra reimagined America in their work, while the new photojournalism of the Farm Security Administration created iconic images by Arthur Rothstein, Dorothea Lange, and Walker Evans, which were published in popular magazines of the time, “introducing America to Americans.”

“Washington Talking Blues” (Talking Dust Bowl) Words and Music by Woody Guthrie. WGP/TRO – © 1961, and 1988 (copyrights renewed) Woody Guthrie Publications, Inc. & Ludlow Music, Inc., New York, NY (administered by Ludlow Music, Inc.)