s Woody pressed east to New York City to join the Almanac Singers for a national tour,* there were doubts that the documentary he was hired on to help with would ever get made.

s Woody pressed east to New York City to join the Almanac Singers for a national tour,* there were doubts that the documentary he was hired on to help with would ever get made.

Even before he left for New York, Guthrie griped in a letter, “Our script … must be okayed in Wash., D.C. before we can get a go ahead sign on the regular film, which I hold very doubtful because of many reasons.”

In reality, the full feature film made strong headway over the next few months after Guthrie’s time in Portland. The Bureau of Reclamation—which managed the Grand Coulee Dam—agreed to help the BPA with the cost of the film “after six weeks of arguing back in Washington,” according to Kahn. It wasn’t really enough money, he said, but they went ahead and filmed scenes for the documentary anyway.

About six months after Woody left Portland, in early 1942, Kahn traveled to New York City to arrange for some of the Columbia River ballads to be recorded professionally for use in the film. Recorded were “Roll, Columbia, Roll”; the minor-key version of “Pastures of Plenty,” which differed significantly from the well-known major-key version that entered the Woody Guthrie canon; and “Biggest Thing That Man Has Ever Done.” Kahn said the government gave him twenty dollars to pay Woody for the recording session—held at Reeves Sound Studios—but that the folksinger impressed him so much he gave him a ten-dollar tip and treated him to a meal at a French restaurant as a thank-you.

Old world meets new world as wool grower Joe Hodgkin and 2,600 sheep cross the Grand Coulee Dam, 1947 (photo credit 7.1)

“I took him to a fancy … really, a reasonably fancy restaurant on Fifty-Second Street, and Woody looked over the menu, which was mostly in French, and he says, ‘Bring me a ’amburger,’ ” Kahn recalled. “The French waiter says, ‘We do not have ze ham-bare-gare.’ … And he says, ‘Steve, ya know, I’ll take you down to the Village, and for fifteen cents you can get an Oklahoma hamburger that’s better than all this crap they’re serving here.’ That was typical of Woody.”

But with the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States had joined the war. At the BPA, as with all other government agencies, energies were soon being directed entirely to the war effort. The public information office churned out a quick documentary about the Liberty ships being produced in Portland with Bonneville electricity. “Power from the Columbia River is building the ships and planes to defend the land we love,” was the new refrain of the agency. Kahn shelved the footage that had been shot and the soundtrack he’d recorded with Guthrie, with hopes of putting the feature film together when the war ended.

Kahn eventually went to Europe with the army and crossed the English Channel to fight, noting later that he had marveled at how America’s air force—built largely with aluminum manufactured in the Northwest with cheap hydropower—had all but vanquished the Nazi Luftwaffe. He also, coincidently, rode in an army boat named after the late J. D. Ross.

Meanwhile, Gunther von Fritsch joined the signal corps and was tapped to make a government film about Franklin D. Roosevelt’s dog. Fala: The President’s Dog came out in 1943.

Woody himself served with the merchant marines three times between 1942 and 1945; the army eventually drafted him in 1945, one month before Germany surrendered.

When the war was over, Kahn’s hopes for getting right back to his feature film proved to be overly optimistic.

World War II left the United States a completely different nation than the one he and Woody Guthrie had written about in 1941. Kahn had hoped that The Columbia would be “like The Grapes of Wrath, which changed attitudes in this country.” With victory secured, the plight of Dust Bowl farmers was a subject a newly optimistic nation cared not to dwell on. Kahn returned to his job at the BPA but didn’t return to the material gathered for his documentary for four years.

It wasn’t until 1948, when a massive flood of the Columbia inundated the Oregon city of Vanport, also known as Kaiserville, that Kahn saw an opportunity to resurrect the film. Vanport was essentially a public housing project developed in a floodplain to give shelter to the thousands of workers who had flocked to Portland to work in Henry Kaiser’s shipyards. Nearly fifty thousand people lived in the 648-acre development, with a disproportionately large black population owing to the fact that many neighborhoods in Portland didn’t allow African American residents. On Memorial Day in 1948, a surging river breached a dike that kept the waters out of Vanport and flooded the homes of eighteen thousand people, 40 percent of whom were African American. Fifteen people were killed by the flood, and the entire city was considered a loss.

The devastation was bad enough that President Harry Truman toured the area. The news also caught Guthrie’s attention. In a letter to a friend in Portland in July 1948, Guthrie complained about his housing situation—a recurring theme in his life—then suggested he had nothing to gripe about. “Can we even worry about a wall around us,” he wrote, “so long as we stand in our thoughts there within eyeshot of the war-town of Vanport where so many thousands of families got their houses knocked down into kindling wood by the same old Columbia River I was singing so many good things about. I think the lack of flood control and power dams that caused this flood to break will give us all plenty to make up songs and to sing about for the rest of our native lives.”

Aerial view of the aftermath of the Vanport Flood, May 30, 1948 (photo credit 7.2)

Kahn’s thinking was very similar to Woody’s. In the late 1940s, many of the same debates over public power were still consuming the Pacific Northwest, among them whether the federal government should build more dams on the Columbia. Kahn saw the Vanport flood as helping the case for dams: more dams meant more flood control, so in his mind the more dams, the better. He said he decided to resurrect the film project “and give Woody another chance to see daylight with those songs.”

The film finally came out in 1949 with little fanfare. It wasn’t the ambitious feature film once envisioned, running just twenty-one minutes and reusing much of the footage shot for Hydro. Three songs—“Roll, Columbia, Roll,” “Pastures of Plenty,” and “Biggest Thing That Man Has Ever Done” are used in the film. But most of the soundtrack relies on reuse of the orchestral soundtrack to Hydro. While the Vanport flood had spurred Kahn back into action, he retained much of the narrative that he and Guthrie had established: the Columbia River projects offered a grand solution to problems that plagued America in the 1930s and beyond. Indeed, the film’s soaring rhetoric seems to make the dubious suggestion that it was Dust Bowl refugees themselves who dreamed up the Grand Coulee Dam irrigation project in the first place.

The Columbia film poster, 1949 (photo credit 7.3)

“The migrants came to the heart of the Columbia River Basin to find land as burned and useless as the dust-stricken acres they had left behind.… An endless string of refugees from the Dust Bowl gazed at the arid acres and moved on. Broken wagon wheels, bleached cattle bones, were warning enough,” the narrator booms as scenes of rolling tumbleweeds and abandoned buildings in the Washington desert are shown. “If they were to find land, they must first bring the Columbia water to the lifeless acres. And Grand Coulee Dam was the answer.”

The movie does lend some striking visual context to Guthrie’s music. In particular, Kahn paired footage of a Dust Bowl family leaving its ruined farm with Guthrie singing the sad opening of “Pastures of Plenty.” And “Biggest Thing That Man Has Ever Done” is played over footage of the construction of the Grand Coulee Dam, celebrating the feat of engineering and construction.

Modern viewers may find it rewarding to hear Woody Guthrie’s songs in this context. At the time of its release, though, it made very little impact on the public and was hardly a vehicle for popularizing Guthrie’s Columbia River ballads.

Rather, as he often did, Guthrie revisited the songs and found other uses for them.

For example, on Christmas Day 1944, NBC broadcast “America for Christmas” on its Cavalcade of America radio show. The episode followed a fictional singing troupe that performed for homesick GIs on a remote South Pacific island. Among the songs performed are “Hard Travelin’,” “Grand Coulee Dam,” and “Pastures of Plenty,” and the chorus of “Roll On, Columbia.” Guthrie himself didn’t sing on the program—Earl Robinson sang lead on most of the songs, but Woody’s songs were getting heard.

Moe Asch of Smithsonian Folkways, New York City (photo credit 7.4)

Also in 1944, Guthrie initiated a relationship with independent record-maker Moe Asch, who eventually released Guthrie’s Columbia River songs commercially. Asch, who started a variety of different labels over the years (including Disc, Stinson, and Folkways), developed a close relationship with Guthrie and granted him a nearly open-door policy at his New York recording studios. Woody either came in alone with a harmonica, or with collaborators like Cisco Houston and Sonny Terry. Because of poorly kept records, there is limited information about these recording sessions. Over the years, there have been attempts to create an accepted discography, but for the most part Woody’s scatteration effect was in play during his relationship with Asch. Still, it’s known that between 1944 and 1947, Guthrie conducted more than a dozen sessions in which he recorded or rerecorded a number of Columbia River songs.

By early 1947, despite their not having been released commercially, the songs seemed to have gained some traction in the Pacific Northwest. In spring of that year, Guthrie traveled to Spokane at the invitation of the BPA’s Ralph Bennett as a guest at a convention of the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association. The appearance in Spokane didn’t go well, but while there he was pleased to hear that his songs were making the rounds. From Spokane, he wrote to Asch in hopes of persuading him to produce an album of Columbia River songs. “They want to see you dish out an album of about 8 sides of my songs (of which I recorded 26 for the Dept. of Interior while on the exterior),” Woody wrote.

Woody’s letter to Moe Asch from Spokane, Washington, 1947 (photo credit 7.5)

Asch was persuaded. When Guthrie returned, they recorded “Pastures of Plenty,” “End of My Line,” “Hard Travelin’,” “New Found Land,” “Oregon Trail,” “Ramblin’ Round,” “Talking Columbia,” and “Columbia Talking Blues.” Shortly after, Disc released the first album of Columbia River songs.

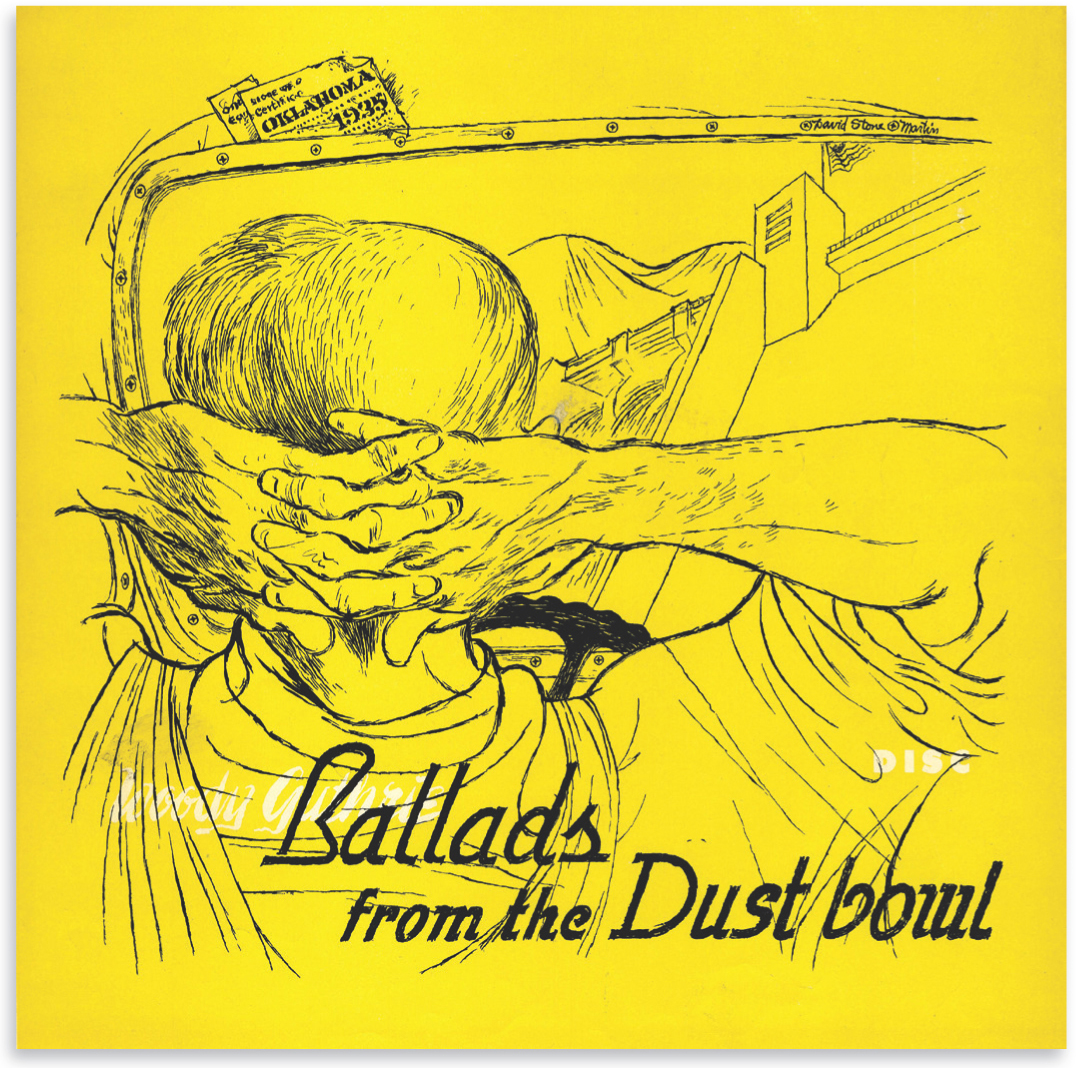

Ballads from the Dust Bowl album cover, DISC Records, 1947 (photo credit 7.6)

This obscure and now out-of-print album was called Ballads from the Dust Bowl, perhaps an allusion to the heavy influence the Dust Bowl had on Guthrie’s outlook on the Columbia River projects. It could also have been a simple marketing ploy to play off Guthrie’s Great Depression brand. Either way, the album art is more to the point: an illustration of a man comfortably reclining in his car as he gazes at the giant Grand Coulee Dam.

Conspicuously absent from both the Asch recording sessions and the Disc album is “Roll On, Columbia,” which Guthrie seems to have largely forgotten about by the late 1940s.

In 1948, Guthrie wrote to a folksinger and former BPA employee in Portland named Michael Loring, asking him for the lyrics to “Roll On, Columbia.” Pete Seeger had asked Guthrie for the words for inclusion in one of his People’s Songs songbooks. (People’s Songs eventually morphed into Sing Out!, one of the most influential publications in American folk music throughout the mid-twentieth century.) At the time of his letter, Guthrie said he was working at a “daycamp for kids,” which he said was “just about as far north as you can get without tromping your foot down on the fascist side of the Canadian boundary line.” Guthrie asked Loring to send Seeger the lyrics to the song, as he himself had forgotten most of them and didn’t have his songbook handy. In fact, the letter suggests that Guthrie had trouble even remembering which song “Roll On, Columbia” was. “I think this is the ballad one, the one that goes: ‘The Indians we killed there at Coe’s little store,’ ” he wrote, choosing perhaps the most unfortunate stanza to cite. In a bit of irony, Guthrie also jokes about making sure Seeger doesn’t add any of his own lyrics to the song; as it turned out, Loring added a new stanza to the song, which has become standard-use to this day:

Tom Jefferson’s vision would not let him rest

An empire he saw in the Pacific Northwest.

Sent Lewis and Clark and they did the rest;

Roll on, Columbia, roll on.

Guthrie never commercially recorded the song, and yet it seemed destined early on to retain a vaunted spot in the pantheon of American folk music.

In the June 28, 1948, issue of the New Republic, none other than former vice president and third-party presidential candidate Henry Wallace cited the song in a column he penned about the importance of folk music in America.

“I am now becoming convinced that when the people are deeply moved by the impulse to take constructive action, they sing. When they are afraid, the spirit of song dies away,” Wallace writes. Later he continues, “One impressive Western singer, for both his voice and his personality, is Mike Loring of Portland, Oregon. We loved hearing him sing:

Michael Loring’s revision of Guthrie’s “Roll On, Columbia” sent to Pete Seeger’s organization People’s Songs upon Guthrie’s request in 1948 (photo credit 7.7)

Roll On, Columbia” Words by Woody Guthrie, Music based on “Goodnight, Irene” by Huddie Ledbetter and John Lomax, WGP/TRO-Ludlow Music Inc. © Copyright 1936, 1957, 1963 (copyrights renewed). Woody Guthrie Publications, Inc. & Ludlow Music, Inc., New York, NY (administered by Ludlow Music, Inc.)

“This song has a tune which even the tuneless can sing,” Wallace writes. “It gives a wonderful sense of the restless might of a great river. I am told that the private-power interests of the Northwest do not like this song, because they feel that the second line may somehow be subversive of their best interest.”

While Wallace credits Loring for singing him the song—no doubt that was true—the editors of the magazine state at the bottom of the page that the lyrics were used with permission of Woody Guthrie.

Thus, it seems, Loring had a vital role in popularizing this song, keeping it alive even as Guthrie forgot about it.

It is a testament to the power of the folk tradition that over the next decade-plus “Roll On, Columbia” spread far and wide in American society without the benefit of a commercial recording until 1960. At the fiftieth convention of the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, held in Spokane in 1955, one attendee suggested that union workers sing the song to Congress to persuade it to approve more dam projects. The notetaker at the convention reported that this suggestion was greeted with applause. In a play about the history of the Pacific Northwest published in 1960, the playwright punctuates the moment that Captain Robert Gray names the river Columbia by having his crew sing “Roll On, Columbia”—despite the implausibility of eighteenth-century sailors singing about electricity. In 1958, a writer in the folk music magazine Caravan states that while Guthrie wrote “several dozen” songs for the BPA, it was “ ‘Roll On, Columbia’ which seems destined to last for generations.” That seemed all but assured, as the song began appearing in a number of children’s songbooks starting in the 1950s. This explains why most people who know “Roll On, Columbia” learned it not by hearing it on the radio but in school and summer camp. In fact, when the song was finally released in 1960, it appeared on a record that accompanied a school book. Not until 1963 did the song appear on an album meant for adults, when the Highwaymen (the folk group, not the country supergroup) and the Homesteaders both released a version of the song.

Guthrie’s letter to Michael Loring requesting a copy of “Roll On, Columbia” (photo credit 7.8)

By this time, the song had already gained wide popularity. This is proven beyond a doubt by another early recording of the song, a rendition that the Weavers performed live at their reunion concert at Carnegie Hall in 1963.

As they sang it, it was actually a medley, opening with a verse from “Roll, Columbia, Roll” and segueing into the chorus for “Roll On, Columbia.” Neither song had ever been a Billboard hit, and the concert was a long way from the Northwest. But the New York City audience obviously knew the second song.

As the fairly obscure “Roll, Columbia, Roll” was sung, the crowd remained quiet. But when once the waltz of “Roll On, Columbia” set in, it was greeted with enthusiastic applause.

*Ironically, the 1941 Almanac tour headed west from New York, and while the group headed home after dates in California, Pete Seeger and Guthrie continued to Portland and Seattle in September. The image of Guthrie overlooking the Pacific Ocean is presumably from this trip, taken somewhere in Oregon.

“Oregon Line” Words and Music by Woody Guthrie. © Woody Guthrie Publications, Inc.