ONE

John Robin

Tucker Mouse was definitely suffering from a touch of spring fever.

It happened every year toward the end of May. The course of the sun swung over just far enough, and a single bright ray was able to dart down through a grating in the sidewalk of Times Square, make its way through a maze of pipes and pillars in the subway station, and land, with a golden splash, right in front of the drain pipe where Tucker lived. Of course, in a week or so the sun would move on, and that ray would have to waste itself up in the streets of New York. But for these few days Tucker Mouse had sunshine on his doorstep—which is something very hard to have, if you live in the subway station at Times Square!

And he had something even more wonderful, too. Warmed by the sun, a few blades of grass were sprouting out of a pile of dirt right next to the drain pipe. Tucker didn’t have any idea how the seeds could have gotten down there in the first place. But there they were—three lovely green blades, poking up through all the soot and dust. Tucker called them his “garden” and watered them twice a day with whatever he could collect in a paper cup from a leaky pipe in the subway walls. They wouldn’t last long either. Even before the sun had moved on, he knew that the grass would be trampled down by all the commuters who streamed through the subway station every morning and evening. It made him sort of sad, to think that his grass would soon be gone.

But today, at least, he had his garden and a puddle of sunlight to sit in as well. And the air was sweet and soft and clean, the way the air gets in the springtime—even in the Times Square subway station—and Tucker Mouse really did have a very bad case of spring fever. It was getting worse by the minute. He had decided to go back inside the drain pipe and take a nap before he fell asleep right there, out in the open, and got himself stepped on, when something caught his eye.

It was a flutter of little wings behind the Bellinis’ newsstand. Tucker peered more closely. Then he called back into the drain pipe, “Harry, there’s a bird in the subway station.”

A few feet within the wall the pipe opened out into a larger space, where Tucker kept all the things he’d collected. Harry Cat was lying back there, stretched out on a pile of crumpled newspapers, half asleep and half awake to the lovely afternoon. “Is it a pigeon?” he asked. Sometimes a pigeon would fly into the station and flutter around for days before it found its way out again.

“No,” said Tucker. “It’s a little bird.”

Harry padded softly to the opening of the drain pipe and stuck his head out where Tucker was sitting. “Where?”

“Over there,” said Tucker. “He’s sitting on top of the Bellinis’ newsstand.”

Harry Cat studied the bird a minute. “It’s a robin,” he said. “See the red on his chest? Now what would a robin be doing down here?”

“Maybe he’s going to take the shuttle over to Grand Central Station,” said Tucker.

“Don’t be silly!” said Harry Cat. “He’d fly.”

Just then the robin flickered up from the back of the newsstand and began to fly around the station. He perched for a second on the roof of one of the shuttle cars—then swooped over toward the Nedick’s lunch counter.

“I think he’s looking for something,” said Harry.

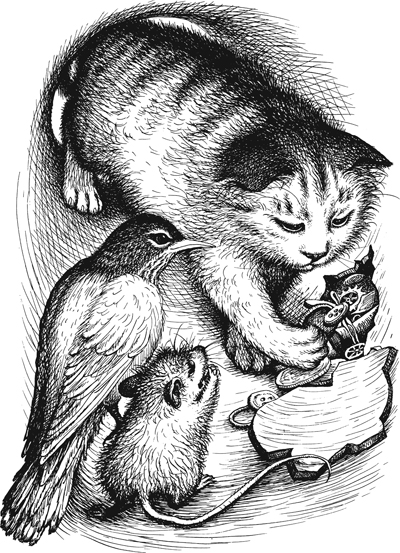

And indeed the robin was looking for something. He whished past the lunch counter and gave Mickey, the counterman, such a start that he let a chocolate soda overflow. Then the little bird darted over toward the Loft’s Candy Store, brushed past its glass windows, circled back over the opening to the drain pipe, and suddenly—much to Tucker’s and Harry’s surprise—dropped down and landed right in front of them.

“Whee-ooo!” said the robin. “Thought I’d never find you.” He hopped up close to the opening and then hopped back again. “You are Tucker Mouse, aren’t you?”

“Yes,” said Tucker. “Who are you?”

“John Robin,” said the little bird. He took a few more hops, back and forth. “And this would be—um—”

“Harry Cat,” said Harry.

“Yes, well, I—uh—” John Robin couldn’t seem to stand still. He would hop up, almost inside the drain pipe, and then quickly jump away again.

“What are you bouncing around like that for?” said Tucker Mouse.

“Well, it’s just that I—uh—I mean, he really is a—a sort of a cat, you know. And up in Connecticut, where I come from, birds and cats don’t—it’s awfully old-fashioned, I guess—but they just don’t get along to well.”

“Harry, he’s scared of you,” said Tucker. “Do something nice to show him it’s all right.”

Harry Cat grinned and said, “What shall I do? Purr a little? MMMMMMMM!” He gave out a long, contented cat’s purr.

“Just don’t eat me!” said John Robin. “That’ll be nice enough. Chester said he was sure you wouldn’t, but—”

“Chester Cricket?” burst out Tucker. “Do you know Chester?”

“Course I know him,” said the robin. “Known him for years. Dorothy and I—she’s my wife—we nest in the willow tree next to his stump.”

“How is he?” said Harry, purring in earnest now because he was so happy to hear some news of his old friend.

“Oh, he’s fine,” said John Robin. “Chipper as ever.”

“Does he still play as beautifully as he used to?” asked Tucker.

“Even more so.”

“What a musician!” Tucker shook his head in wonderment. “Did he tell you about what happened to him down here in New York?”

“Oh yes,” said John Robin. “When he got back last September, he told us all about it. Very nice, I’m sure. But you know, we’ve got a lot of good musicians up in the Meadow.” The little bird cocked his head rather proudly to one side. “Far as that goes, I’m not a half-bad singer myself! But there’s no time to talk about that now. I’m here on serious business.”

“Come in the house,” said Tucker. “It’s almost time for the commuters, and I wouldn’t want any friend of Chester’s to get trampled on.”

The cat and the mouse turned and went into the drain pipe, and John Robin, after one dubious look at the dark opening, hopped in after them. They all went up to the pocket inside and made themselves comfortable on the newspapers.

“Now what’s the serious business?” said Harry Cat.

“We’ve got big worries up in the Old Meadow,” said John Robin. “Chester and Simon Turtle are just worried to death. They’re sort of the heads of the Meadow—Simon because he’s the oldest person there, and Chester, well, just because he’s Chester—and they’re almost frantic. We all are!”

“What’s the problem?” asked Tucker.

“I’d rather wait and let Chester explain it to you himself,” said the robin. “The point is, I was sent down to New York to ask you—in fact to beg you and Mister Cat here—”

“Call me Harry,” said Harry.

“—to beg you and Harry to come up to Connecticut right away! Chester said that you used to be his manager and that you were very good at solving problems.” The robin shook his head hopelessly. “And I’m here to tell you, we’ve sure got a problem up in the Old Meadow!”

Tucker looked at Harry and then looked back at John Robin. “Well, I don’t know,” he began. “Harry and I have talked about going to see Chester some time, but Connecticut’s an awful long way away, and—”

“Oh, please!” interrupted the robin. “Connecticut’s not so far. And if a little cricket like Chester could take the train up there, two big fellows like you certainly can too! We need you terribly! Honest! If you don’t come, I don’t know what we’re going to do!” John Robin was so upset and anxious that he hopped around frantically and got his claws all tangled up in torn newspapers. But he quieted down after a while and just stood staring at the floor of the drain pipe.

For a minute or so everyone was silent. Nobody looked at anybody. Then Harry Cat said quietly, “We’ll go.”

Tucker Mouse shrugged. “So—we’ll go.”

“Thank goodness!” The robin was so relieved that he burst out in a little, spontaneous song.

“When shall we leave?” said Harry.

“Could you come tonight?” John began bobbing up and down impatiently. “We could take the Late Local Express, the way Chester did.”

“Tonight?” Tucker Mouse jumped up on his feet. “But I have to pack!”

“What do you have to pack?” said Harry Cat quizzically.

“Why, why—everything!” announced the mouse.

“Everything?” Harry looked around the drain pipe skeptically. Tucker’s possessions were piled all over—in corners, on top of newspapers, under newspapers, everywhere.

“Of course!” said Tucker. He dashed over to one corner, picked up the heel of a lady’s high-heel shoe, and cradled it gently in his arms. “You don’t think I’d leave this beautiful heel here, do you?” He dropped the heel and dashed over to another corner. Shreds of newspaper flew up in a gale as he rummaged amid the mess. Then he held up two tiny white pearls. “And my pearls! Surely, Harry, you remember who it was who dashed out last January, when that lady’s strand snapped, and salvaged these beautiful pearls!”

“It slips my mind,” said Harry innocently.

“It was me!” said Tucker. “And right during rush hour too!”

“Well, they’re only fake pearls,” said Harry.

“Fake or not, they’re mine!” shouted the mouse. “You know, Harry, you and me aren’t the only people living in this subway station. There’s a pack of dishonest rats living in the drain pipes on the other side, and they would love the chance to swipe a few of my things!” Another thought struck him; he dropped the pearls and clutched at his heart. “Oh, my buttons! My beautiful collection of buttons!”

“Now quiet down,” said Harry Cat. As Tucker was dashing off to find his buttons, the big cat lifted his right front paw and brought it down on the mouse’s back, squashing him—very gently—to the floor. That was how he helped his friend relax when Tucker got too excited.

“Harry, if you wouldn’t mind—the paw, please, Harry—if you wouldn’t mind.”

“Will you be reasonable?” said Harry.

“I’m always reasonable,” said Tucker Mouse.

Harry lifted his paw, and Tucker stood up. “And besides my heel, my pearls, my buttons, and all the keys, hairpins, and everything else I’ve managed to scrounge up through the years, what about this?” Very grandly Tucker marched across the drain pipe and pulled aside a sheet of paper propped against the wall. There, neatly piled up, were two dollars and eighty-six cents, in pennies, nickels, dimes, and quarters, with one big half dollar on the bottom. “My life savings!” proclaimed Tucker Mouse. “And wouldn’t those rats love to get their claws on this! Believe me, Harry, they wouldn’t spend it on charity!”

“I’ll take care of everything—once and for all!” said Harry Cat. Usually Harry moved in a slow, stealthy way, but sometimes he moved like lightning—as he did now. Before either Tucker or John Robin knew what was happening, the big cat began to sweep all Tucker’s valuables into a heap.

Tucker was frantic when he saw what was happening. “Harry, stop! What are you doing? Oh—my buttons! Don’t scratch the pearls! My life savings—!”

In a cascade of silver Harry pushed over the column of small change and added it to the mound of Tucker’s possessions. Then, with one paw, he pulled away a little section of the drain-pipe wall and revealed a dark hole. As Tucker danced around madly, shouting, “It won’t be safe! It won’t be safe!” Harry scooped all the things inside the tiny cave and replaced the section of wall. “There!” Harry said, when the work was finished. “And it will be safe!” He rubbed his fur back and forth against the spot where Tucker’s treasure had disappeared. “I’ll leave a lot of cat smell here. Any rat who noses around will get the daylights scared out of him!”

“Ruined!” Tucker Mouse wrung his two front paws. “I’m ruined. The fruits of all these years of scrounging—gone!”

“And they’ll still be here when we get back,” said Harry Cat. “Now how about something to eat? John must be hungry if he flew all the way down from Connecticut—aren’t you, John?”

“I don’t want to be any trouble,” said the robin, who secretly was famished but didn’t think he’d find anything he liked to eat in New York.

The thought of food made Tucker perk up a little. “What’s your preference?” he asked the little bird.

“Oh—worms, mostly,” said John.

“Worms I don’t have,” said Tucker. “And don’t want.”

“I also like seeds,” said John Robin.

“Seeds. Hmmm.” Tucker Mouse wiggled his whiskers—which helped him think. He went over to the part of the drain pipe he called “the pantry,” where he kept all the bits of sandwiches and candy bars and other things he picked up around the lunch counters in the station. A minute’s fumbling and he had found what he was looking for—a big crust, which he brought over and set down in front of the robin. “It’s from a seeded roll,” he said. “You could peck out the seeds.”

John took a peck at the crust. “Delicious! Never tasted anything like it!”

“A mere poppyseed roll,” said Tucker with a wave of his paw. “New York is full of such wonders.”

“And after we eat I want to hear you sing some more,” said Harry.

“Be glad to,” said John Robin with a mouthful of poppy seeds.

About half an hour later a man named Anderson was passing through the subway station on his way home to New Rochelle. He heard something and stopped to listen. The sound stopped too. But then, in a moment, it started again. Mr. Anderson shook his head. He knew it was impossible, but it actually sounded like a little songbird—singing to his heart’s delight inside that drain-pipe opening.