ELEVEN

How to Build a Discovery

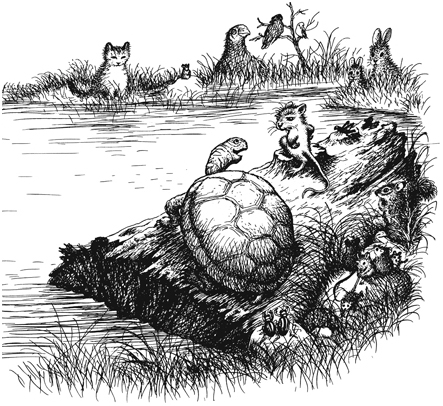

Like a wind, word spread through the meadow that the mouse from New York had another plan. From all quarters, animals streamed toward Simon’s Pool. By noon a great crowd had collected around the log where the old turtle sunned himself. He was lying there now, waiting like the others to hear what Tucker had to say. The mouse jumped up on the log beside him and looked out over the upturned, expectant faces before him.

“Friends and meadow dwellers!” he began. “As you know, the ripping up of your home has already begun.” A groan went up from the assembly. “Those humans should only have known better!” said Tucker. “But just this morning I came down with an idea that still might work!”

“Hooray!” came a cry from the section where the sundry fieldmice were sitting.

“Save the ‘hoorays’ till we’re safe!” said Tucker. He went on to explain what had happened. “Just a little while ago we discovered that the farm house where Henry and Emily live had been the home of a man named Joseph Henry, and I got the idea that—”

“Joseph Henry!” exclaimed Simon Turtle. “Why, I haven’t heard that name for—for—goodness, I can’t even recollect how many years!”

“Very interesting, Mr. Turtle,” said Tucker, who was anxious to get on with his plan, “however, right now—”

But Simon had begun one of his reminiscences—an especially interesting one, to him, because it brought back a scene he hadn’t remembered for ages. “I recollect my grandfather—Amos Turtle was his name—and I recollect him telling me when I was just out of the egg that his grandfather—that would be my great-great-grandfather—”

“Mr. Turtle—!” Tucker began tapping his foot.

“—his grandfather,” Simon went right on, “had told my grandfather that he remembered the days when the Henry family was still living in that farm house. He told him about the night of the fire. I recollect my grandfather saying that the Henrys used to have an old dog, and the dog knocked over a kerosene lamp—way back in those times, before electricity, they used kerosene—and—”

“Mr. Turtle!” Tucker Mouse burst out impatiently. “If you’ll let me tell you about my plan, and if my plan does work, maybe your grandchildren will have something to recollect, too!”

Tucker’s indignation shocked Simon out of his reveries back into the present. “Oh, by all means,” he said, “do go on.”

“To be brief,” said Tucker, with a stern look at the turtle, “what we have to do is convince the human beings that that farm house originally belonged to Joseph Hedley, not Joseph Henry. You said that the human beings didn’t know exactly where Joseph Hedley lived, didn’t you, Chester?”

“Yes, I did,” said the cricket, “but—”

“Wait.” The mouse held up one claw. “If we can get the human beings believing that the Old Meadow was the location of the Joseph Hedley homestead and farm, my guess is that they won’t dare wreck a place of such—” His squeaky voice became very grand and important. “—such historical significance! So we’ve just got to fool the stupid human beings. How about it? What do you think?”

The animals all looked at one another, testing the idea in their minds. Then a few began to smile, and a few more began to laugh. A wave of excitement and enthusiasm broke over them. To fool the human beings would be a game, as well as a means of saving the Old Meadow.

“Here’s how I think we can do it,” said Tucker. “First we—”

“Uh—Tucker,” said Chester Cricket, “excuse me for interrupting you. But even if we can do it, wouldn’t it be sort of—well, I mean, like a lie?”

“Oh, Chester!” Tucker shouted. “You’re so honorable! It’s disgusting! Here the human beings are about to ruin your home! Everybody’s home! And you’re worrying about telling a little lie! The only other thing I can think of to do is wait until Monday morning, and then have all of us who have teeth big enough go out there and attack those workmen! We might get the town believing the meadow was full of rabid rodents. But they’d probably just come out here and exterminate us anyway!”

“Chester,” said Harry Cat, “just keep telling yourself it’s not a lie—it’s a benign deception. For everybody’s good.”

“That’s right!” said Tucker. “A ‘benign deception.’ For everybody’s good! The human beings’ good, too—if they don’t have brains enough to leave nice meadows alone!” Another idea struck him. “And imagine the noble sentiments, Chester! How proud they’ll all be—to have discovered the Joseph Hedley homestead. I could weep to think of the patriotism!”

“Well—” began Chester.

“Fine! That’s settled!” said Tucker Mouse. “Here’s what we do: first of all, the various and the sundries have to ransack that cellar hunting for things that don’t look old—very old! If you have any doubts—about dishes, say, or furniture—ask either Harry or Chester or me. But anything that doesn’t look at least a couple of hundred years old—drag it out of the cellar and hide it somewhere! Hop to it now, you rabbits and mousiekins!” Tucker was really getting in the spirit of things; he clapped his paws and rubbed them together like the foreman of a crew. The various rabbits and sundry fieldmice dashed off toward the ruins of the farm house.

“We’d like to help, too,” said a cultured voice from one side. Beatrice and Jerome Pheasant had been sitting a little apart from the others.

“Great!” said Tucker. “You two go with the various and the sundries. And scrounge, Beatrice! Scrounge like you never scrounged before!”

Beatrice Pheasant looked a little shocked on receiving these instructions. Needless to say, she had never “scrounged” before in her life. And she didn’t relish the idea of spending the day in the company of a crowd of ordinary fieldmice. But she realized that this was an emergency, so she swallowed her pride—and told Jerome to swallow his, too—and off they fluttered. As a matter of fact, by late afternoon she found that she rather enjoyed this “scrounging”—or “antiquing,” as she preferred to call it. It was she who uncovered a solid silver spoon. Everyone thought that a solid silver spoon was exactly right for the Joseph Hedley homestead. But then Beatrice, with her sharp pheasant eyes, noticed that down at the end of the handle there was printed in tiny figures the date when the spoon had been made: 1834. It was decided that 1834 was far too recent a year for Joseph Hedley to have owned the spoon. Beatrice said that in that case she would like to have it herself, and she took it back to her nest. The other things that were too new—a Campbell’s soup can, for instance—were carted off and buried in the orchard.

While work went on in the cellar, Tucker Mouse was still issuing commands beside Simon’s Pool. “Now the most important thing—and this is a job for you, Harry—is to get that sign we saw in the Hadleys’ attic. Remember that sign we saw, that had HADLEY stamped on it in iron letters? I have to have it! It’s the key to everything!”

“I can help you there,” said Bill Squirrel. “There’s a hole under the eaves of the Hadleys’ roof big enough for two squirrels to march in abreast. And we have, too! There’s more that goes on in those attics than the human beings know about.”

“Wonderful!” said Tucker. “Then you help Harry. But wait till the Hadleys have gone to sleep—it’ll be easier then.”

“Hadley’s not the same as Hedley,” said Harry Cat.

“Never you mind,” Tucker silenced him. “Just you watch what I’m going to do! And don’t let me forget that I’ve got to chew off part of the first page of Joseph Henry’s family Bible.”

“What are you going to do that for?” said Harry. “That ought to be lugged away, too. It’s a sure giveaway.”

“Not when I get through with it, it won’t be!” said Tucker. “I’m going to doctor it up so it reads Family Bible of Joseph He—and then the page ends. The human beings’ll think the He—stands for Hedley. And what could be more precious to the town of Hedley than the family Bible of Joseph Hedley himself? Hic! hic! hic!” He couldn’t contain himself and burst into a series of squeaky laughs. “You shouldn’t be upset, Chester—it’s just another little benign deception.”

Chester couldn’t help but laugh himself. He shook his head. “You’ve got to admit it—when Tucker works at something, he really works at it!”

Tucker Mouse gave a superior little sniff. “You said it!” he agreed. “This is one mousiekins with imagination!”

* * *

Ellen and the little kids continued to picket almost all the afternoon. They didn’t know it, but on this particular Saturday they weren’t the only ones who were working to save the Old Meadow. In the ruined orchard, through the portal oaks, and down inside the farm-house cellar there was a bustling of activity such as the meadow had not seen for years. Fieldmice were chewing up an old canvas suitcase. Chester said it could stay in the cellar, but only if it looked more torn and shredded. Rabbits were scratching up a set of wooden bowls. They had aged very nicely and been partly burned in the fire, too—exactly the kind of clues Tucker wanted. Beatrice and Jerome Pheasant, having appropriated the silver spoon, were now sifting through a pile of broken glass, picking out the most weathered pieces and flying the rest over to a hole Henry Chipmunk had dug on the far side of the orchard.

And Tucker Mouse was running around everywhere, shouting encouragement. “Remember! It has to be all finished by picnic time tomorrow! Hedley Day is the only time when lots of human beings come to the meadow, isn’t it, Chester?”

“Yes,” said the cricket. “And besides, if this doesn’t work tomorrow, by next week it’ll be too late anyway.”

Tucker kept looking into the west and wishing the sun would go down. “I’ve got to get that sign!” he said. When night finally did come, he and Bill Squirrel and Chester went back to the hill and waited for the lights in the Hadleys’ house to go out. Work didn’t stop in the cellar, however. There was a full moon for the animals to see by, and the sifting and searching went on all night.

It was a habit of Mrs. and Mr. Hadley to sit up late on Saturday nights and watch a movie on television. On this night the movie was one of their favorites. They had seen it years ago, even before Ellen was born, and it was like being young again to see it once more together. They enjoyed it very much.

Tucker Mouse did not enjoy it, though. By midnight he was bouncing around like a rubber ball. “What are those people?” he demanded impatiently. “Human beings or night owls?”

“Harry must be getting awfully nervous, too,” said Chester.

“Mmm,” grumbled Tucker. “He’s been living over there like a king all summer—now let him do his duty for once!”

“There it goes!” said Bill Squirrel. The light in the master bedroom had just winked out. “Now is that sign all you want? What if I find something else that looks really old?”

“Steal it!” said Tucker happily. Then, to ease the cricket’s conscience, he added, “Now now, now now—just grit your teeth, Chester. Win or lose, it’ll all be over tomorrow.”

Bill darted across the road, up the Hadleys’ lawn, and flickered up a maple tree that grew in front of the house. Its branches overhung the roof, and in a second he was inside the attic. Harry Cat was waiting for him. He pointed to the sign. In the dim moonlight that entered through a narrow window the iron letters—HADLEY—stood out. Without a word, the squirrel and the cat began dragging it to the hole where Bill had entered.

That part of the attic was just above Mr. and Mrs. Hadley’s bedroom. Mrs. Hadley sat up in bed. “Dear,” she said, “I hear something in the attic.”

“What?” mumbled Mr. Hadley, who was half asleep.

“I don’t know,” said Mrs. Hadley. “But I’ve told you a dozen times I think squirrels are getting in up there.”

“I’ll look into it tomorrow,” said Mr. Hadley into his pillow.

“It’s not the first time I’ve heard that,” said Mrs. Hadley. She rolled over and went to sleep.

Bill and Harry pulled and hauled the sign to the hole under the eaves of the roof. “Better just push it out,” the squirrel whispered. They counted three and heaved. Down fell the sign, missing the flagstone front walk, on which it would have made an awful clatter, by a couple of inches. It dropped, with a soft thud, on the grass. Harry decided that it was easier to follow Bill Squirrel than go down the stairs inside the house, so he too climbed out the hole, over the gutter, and onto the roof. “Kind of like housebreaking, isn’t it?” Bill laughed in the darkness. They both jumped up to the branch of the maple tree and made their way down to the lawn. From there it was no problem to lug the sign across the road.

“About time!” said Tucker Mouse when he saw the two of them emerging from the night.

“I’m going back and look for some old things now,” said Bill. Before Chester could say that he thought they had enough, he had vanished back toward the Hadleys’.

“Well, here’s the sign,” said Harry. “What are we going to do with it?”

“This is what I’m going to do!” said Tucker. He began chewing furiously at the wood around the letter A.

“You’ll get splinters in your tongue,” said Chester.

Tucker spit out a mouthful of wood. “I don’t care where I get splinters—as long as this plan of mine works!” He resumed his chewing. The nail that held the letter in the wood was deeper than he had thought it would be. It took almost an hour to get it loose. Then Tucker and Harry each took an end of the letter and pushed it and pulled it until they had rocked the A out.

“But look,” said Harry. The shape of the A was clearly pressed into the wood where it had been. “It still looks like HADLEY, but with one letter missing.”

“Nothing unexpected,” said Tucker confidently. “Don’t worry.”

Just then Bill Squirrel came back. In one claw he was carrying a colored glass necklace and in the other a pair of plastic earrings with tiny copper beads in them. “Guess what I found!” he exclaimed proudly. “A box of Mrs. Hadley’s jewels!”

“Jewels—” said Chester in dismay. “Now that really is going too far!”

Tucker Mouse, who had collected some lost jewelry himself in the Times Square subway station, trotted over to have a look. After a preliminary examination he said disappointedly, “It’s only costume jewelry. Kind of pretty, though.”

Harry Cat switched his tail back and forth. “Somehow,” he said softly, “I don’t quite think that a glass necklace or a pair of plastic earrings are what you’d expect to find in a pioneer’s homestead.”

“Hmm.” Tucker brooded on that a minute. “I tell you what. If my plan succeeds, I’m sure to deserve a reward. I’ll keep the necklace, and you can give the earrings to Beatrice Pheasant. She’s starting a collection, too. And if she keeps on scrounging the way she did today, she’s going to end up as good as me!”

Chester Cricket sighed and decided not even to think of words like “burglary” until tomorrow night.

“Well—back to work!” said Tucker. He started on the sign again—not chewing now, but nibbling at the wood where the letter A had been nailed. Before long, the impression of the A had been completely erased. Tucker spit out the bits of wood and took a deep breath. “Now for the most important part.” Very carefully he nibbled a bar that went straight up and down on the sign. Then, off that bar, he nibbled three shorter, parallel bars. The shape of a perfect capital letter E appeared.

“I get it!” said Bill. “They’ll think the sign said HEDLEY, but the E dropped out!”

“Right!” said Tucker. “And now, just to make it look really old—” He chewed away the wood around the L, until the iron letter came loose. “I don’t want this one to come off,” said the mouse. “Only be wobbly with age.” He stood back and squinted at the sign, like a painter appraising his masterpiece. “Hmm. Still something wrong. It’s the sides.” Two elegant scroll-like curves were carved into the wood at the ends of the sign, the kind of detail that people in Connecticut like. “Too fancy for a pioneer. Bill, you take that side and I’ll do this.” The squirrel and the mouse did a few minutes of vigorous chomping. And now the sign really did seem like the wrecked and weathered relic of a bygone age. “There!” said Tucker. “Finished! How’s that for a ‘benign deception’?”

“Very good!” said Harry Cat. “As a forgery it’s not bad either.”

A groan was heard from Chester Cricket.

The animals dragged the sign down the hill, dunked it in Simon’s Pool to wash off the chips and also give it the feeling of having been out in the rain and the wet all those years, and then carried it up to the farmhouse cellar. The last of the exhausted sundries were just crawling home.

Tucker insisted on going down into the cellar to arrange the sign properly. First he tried it here, then there, then way over there, then back here—but he couldn’t be satisfied. “For goodness’ sake!” said Harry Cat. “You’re not decorating a castle!”

“I know,” said Tucker. “I’m furnishing a ruin. But it has to be just right.” He finally decided that behind the rosebush was the proper place. That was near enough to the Bible so that they could be found together, but not too near to arouse suspicion. His last bit of nibbling, just as dawn was beginning to break, was to snip off neatly the last three letters of Joseph Henry’s name. In the pale, growing light the mouse looked around him. “Well,” he asked, “does this look like the ruins of a pioneer’s homestead—or doesn’t it?”

“I don’t know,” said Harry. “I’ve never been in one.”

“Anyway,” sighed Tucker Mouse, “after all the work I’ve done tonight, I feel like the ruins of a pioneer!”