Copycat Inflations in Seventeenth-Century Europe

This chapter describes how several European countries were tempted to replicate the Castilian experiment with token coins. Some resisted but others accepted the temptation and took the inflationary consequences.

France: flirting with inflation

France was tempted to copy the Spanish experiment, but ultimately refused. In France, the realization that mechanized minting allowed a fiduciary coinage dawned at the same time as in Spain. Before 1575, France’s small denomination coins had been made of billon. The French had set up the Mill Mint, a mechanized mint, in 1552 (see chapter 4). In 1575, it produced the first pure copper coins, with an intrinsic content worth about 45% of the face value. To quote Blanchet and Dieudonné (1916, 172): “The date of this reform is important: in distinction with medieval currency which, however alloyed, had never had value but for its content of fine metal, we see the birth of subsidiary fiduciary coinage, thanks to the progress in public credit, as well as to a sharper understanding of the relative roles of metals in circulation.”

Limited minting of pure copper coins continued for a time. In 1596, it was decided that all pure copper coinage would be made exclusively at the Mill Mint, and little was produced. From 1602 to 1636, however, the French king began granting private individuals licenses to produce copper coins using presses. The coins were legal tender. The licenses limited the total coinage, and the Cour des Monnaies tried to restrict these issues. Throughout this period, imitations of French copper coins were minted in foreign enclaves and territories adjacent to the French kingdom (see fig. 4.8), and typically circulated in rolls. 1

However, when mechanized minting was extended to all mints in 1640, new emissions of pure copper soon followed, small amounts in 1642 and 1643, and much larger ones between 1653 and 1656, at a time of extreme political crisis. 2 The minting was subcontracted to private entrepreneurs who established presses in small towns with water mills. The amounts remained small, however, at least in comparison with the Spanish experience. The output of 1653–56 was equivalent to 1.6 million Spanish ducats and amounted to 2 or 3% of the French money stock. France had thus considered following Spain’s policies but had refrained from excessive issues of token coins after numerous warnings from monetary officials.3

Catalonia

In 1640, the Catalonians rebelled against the king of Spain and signed a treaty with France that made the king of France the count of Barcelona and prince of Catalonia. It took the Spanish troops until 1652 to retake Barcelona and most of Catalonia, but the Roussillon region around Perpinyà (Perpignan) remained in French hands. Fighting continued inconclusively until 1659, when Spain ceded the part of Catalonia north of the Pyrenees to France.

During that period, a number of Catalonian towns (Mailliet 1868–73 lists over twenty) issued copper coins; some, like Vic, Perpinyà, Gerona, Puigcerdà, and Villafranca del Panadès, had issued convertible small change in earlier years. It appears, however, that this time the convertibility of the copper coin was not guaranteed, and large emissions followed.

Usher (1943, 459–63) and Colson (1855) provide information on copper issues in Barcelona and Perpignan respectively. In Perpignan, the city council asked the French viceroy in 1643 to authorize issues of coins of 6d., 12d., and 24d. with the usual content. A few months later, however, citing difficulties in securing the silver content, they asked permission to put less silver in the 12d. and 24d. coins, and none at all in the 6d. coins; the viceroy, initially reluctant, finally agreed. In 1646, a further issue was authorized. Counterfeiting immediately became a problem. Inspectors were appointed to stamp the authentic coins and destroy the fakes. Surrounding towns refused to accept the copper coins, but Perpignan took them to court and won a ruling by the supreme court of Catalonia.

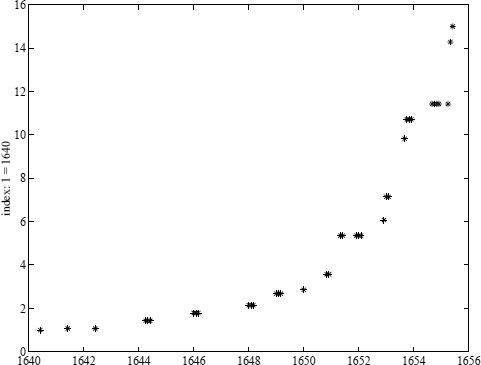

Figure 15.1 Index of the price of the gold doubloon in sous, Perpignan, 1640–56. Source: Colson (1855, 141–42).

Significant inflation resulted, as shown in figure 15.1 which plots the price of the gold coin in Perpignan.4 The scale of the inflation, a factor of 15, indicates that the market value of the copper coinage, initially overvalued by a factor of 13 to 14, had been driven to its intrinsic value. After the inflation ended, the French government tackled the problem of debts contracted during the inflation. To index repayments, it established a price series for the gold coin, which forms the basis of figure 15.1.

Germany

In Germany, efforts by successive Emperors since the fifteenth century to coordinate the coinage policies of the many constituent states of the Empire culminated in an imperial mint ordinance (Reichs-münzordnung) of 1559. This left the responsibility for minting coins to selected group of princes, but fixed the intrinsic content of coins throughout the whole denomination structure, and made small coins full-bodied. This arrangement led the official mints to produce only large denomination coins (silver thalers thaler and guldiner) and caused a shortage of small change that was increasingly met by unauthorized mints that produced light-bodied coins. Over time, these coins became lighter, so that by 1610 they were already 20 to 25% lighter than prescribed in the mint ordinance.

When the Thirty Years War began in 1618, the stage had been set for what became known as the Kipper- und Wipperzeit, “the clipping and culling times.”5 Throughout Germany and the Habsburg lands, local princes as well as private mints competed with each other and produced progressively more debased petty silver coinage (groschen, kreutzer, pfennig), driving the intrinsic content to ⅛ of the amounts prescribed in 1559. Some states even issued pure copper coinage. People queued at the mints to turn their copper pots and pans into coins. The metal content of the large coins remained unchanged. The prices of such large coins (the gold florin and the silver thaler) in terms of the small coins are tracked in figure 15.2. Commodity prices also increased greatly, although not quite as much. The inflationary episode ended abruptly in 162 3, when the princes’ deteriorating tax revenues from issuing coins induced them to return to a better standard. However, another episode of inflation, less spectacular and more drawn out, was to take place in the late seventeenth century (the so-called second Kipper- und Wipperzeit).6

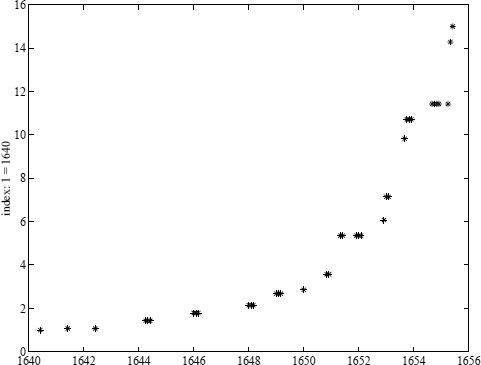

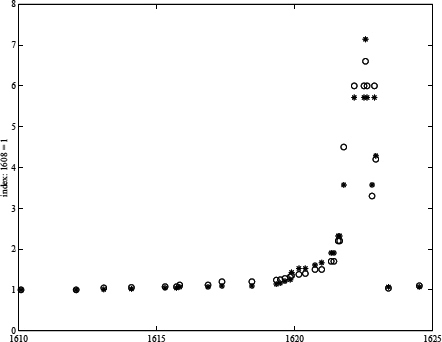

Figure 15.2 Price of the Gold florin (circles) and the silver thaler (stars) in terms of Kreutzer coins, Bavaria. Source: Altmann (1976, 272–73).

The scale of inflation evident in figure 15.2 even surpasses Castile’s experience, with the price of silver coins tripling from March 1621 to March 1622. 7 Minted quantities for all of Germany cannot be known, but there is information for Saxony, a major state and important silver-producing area. In the twenty years preceding the inflation, Saxony minted 0.4 million fl. per year, almost all in large silver coins. During the four years of the Kipperzeit, at least 12.5 million fl. in small coins were minted, 5.5 million fl. in Dresden alone. During the following 28 years, 0.1 million in large silver coins were minted per year (Wuttke 1894, 142).

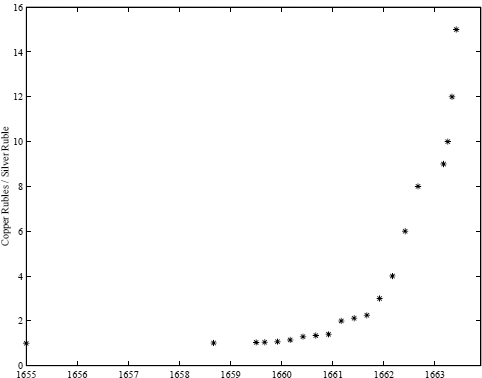

Figure 15.3 Exchange rate of copper rubles to silver rubles, Russia, 1655–63. Source: Chaudoir (1836, 1329–30).

As Richard Gaettens wrote (1955, 95): “From the point of view of monetary history the Kipperzeit had undoubtedly also a positive side. Indeed it became apparent that alongside the main currency a fiduciary money was needed for small change. … The development of subsidiary coinage received in the Kipperzeit its decisive impulse.”

In the second half of the seventeenth century, large issues of small coins and a consequent appreciation of the large currency recurred in eastern Germany and in Poland. While engaged in a war against Poland, the Russian czar began to mint pure copper imitations of silver rubles in 1655, and decreed that they should exchange at par with the latter. Initially successful, this currency collapsed after a few years. The pattern shown in figure 15.3 (stable exchange rate for several years, followed by a rapid collapse) resembles the Castilian experience. In 1663, the mint repurchased the copper rubles at 1% of their face value.8

The Ottoman empire

A final example comes from the Ottoman Empire. In the 1680s, the Ottoman rulers hired a Venetian convert to construct screw presses and replace the old hammering method. The first use of the new machines was to produce massive amounts of copper coinage from 1687 to 1690, when the mankur, whose copper content was worth about 0.14 silver âkçe, was ordered to pass for 1 âkçe (Sahillioğlu 1983, 289; Pamuk 1997).

1 Spooner (1972, 174–78, 185–92, 336–39).

2 The output was 300,000 livres in 1642–43 and 7.3 million livres in 1654–56.

3 Spooner (1956) documents the opposition of the Cour des Monnaies.

4 The price series for Barcelona (Usher 1943, 466) tracks figure 15.1 closely, but stops in 1653 when the town came under Castilian control again.

5 Gaettens (1955, ch. 4), Rittmann (1975, ch. 9–12), and Sprenger (1991, ch. 7) for general surveys and references to the numerous regional studies. See also Schmoller (1900) in the context of the evolution of monetary policy with respect to small coins. A brief treatment in English is Kindleberger (1991). This episode has attracted little interest in the English language literature, even though German writers called it “the Great Inflation”—until 1923, that is.

6 See also Schönberg (1890, 1:336) on the large-scale recourse to copper coinage in Prussia between 1764 and 1806.

7 Redlich (1972, 12) notes the similarity with the Castilian inflation.

8 See Chaudoir (1836, 128–30) and Bruckner (1867) on Russia, Bogucka (1975) on Poland.