I SUPPOSE I GOT INVOLVED in backyard sugarin’ the day my determination to make maple syrup ran smack dab into my good wife’s determination that the boiling down not be done on the kitchen stove. I must say she has a point. You see, the main thing about making maple syrup is you have to boil off about 32 parts of water in the form of steam to end up with one part of maple syrup. (This is a reliable ratio for my part of New Hampshire, but 40 parts could be closer, depending on the location, weather, time of the season, and other mysterious factors.) That means that if you’re boiling down a batch some Saturday afternoon on the kitchen stove and are aiming, say, for 3 quarts of syrup, you’re going to put about 24 gallons of water into the air in the form of steam before the boiling’s done. Unless you’ve got one awful powerful exhaust fan, you end up with water streaming down the walls and enough steam to impair visibility across the room. And, when things finally do clear, you’re apt to find the wallpaper lying on the floor. Then too, even if the batch doesn’t boil over on you, which it can, the sugar in the spray from all that furious boiling gets all over the stove and is harder than blazes to get off. So, if you want to maintain a measure of domestic tranquility, the best thing is to do your boiling—most of it anyway—outside, or in a garage or a shed if you’ve got one handy.

Anyway, the day I lost my kitchen privileges was the day I started figuring out in earnest what I might need to set up a proper evaporator in a little sugar house and get the equipment necessary to do the job right. I was soon up to my eyebrows in catalogues and books on the time-honored equipment and methods used to make maple syrup. This all made good reading, but the smallest evaporator I could find at that time was designed to handle up to 250 buckets, capable of producing about 75 gallons of syrup during the season, and it cost better than $600. When I went to figure out the buckets I’d need to collect enough sap to make it worth while to run the evaporator, plus the holding tanks, instruments and other gear, not to mention building a small sugar house to house everything in, I was looking at an investment well up into four figures. It became clear I’d have to get into the business of selling syrup just to make ends meet.

Having other business to attend to, I wasn’t about to make that kind of commitment to sugarin’, but I was just as determined to make my own syrup—say 3–4 gallons a year. I had my own sugar maples, plenty of firewood, an attraction to maple sugar like a bear has to honey, and enough Yankee (or maybe it’s Scotch) blood in me to take pride in saving upwards of $12 a gallon in the process.

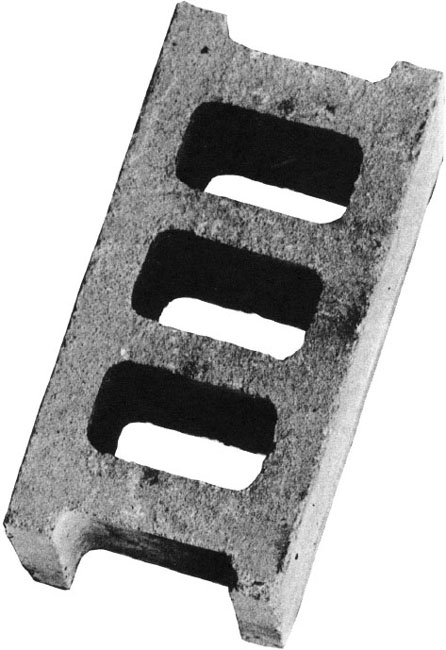

So, the only solution was to improvise. I scrounged up an old 18" x 24" hotel baking pan, built a firebox under it out of cement blocks, with some used stovepipe sticking out the back, and produced a very satisfying batch of golden delicious right out there in the backyard.

That was just the beginning. During the course of the season I ran into, and then started searching out, other backyard operators. We always took time to inspect each other’s rigs and to speak kind words about some particularly innovative piece of equipment, be it a rotating bent stovepipe to create a venturi draft effect, or a bathtub holding tank. Naturally we’d steal each other’s ideas and make constant modifications in our own rigs during the season, and we’d swap theories on what kind of maples produced the sweetest sap and what methods should be used to tell when the syrup was ready to be “drawn off.”

The real challenge in backyard sugarin’ is to find ingenious ways to collect and boil down sap without spending any money, and I must say I found a whole breed of like-minded people. Backyard sugarin’ builds interesting friendships, a kind of fraternity, I suppose, born of a mutually parsimonious nature.

I like to think, too, that most backyard sugarers must have a little of the moonshiner’s blood in them. And, there are a surprising number of similarities between boiling maple sap and distilling out the old mountain dew. In both cases you’re separating water from something else. In the case of sugarin’ you want what’s left in the pan after the boiling, while with moonshining it’s what comes off that counts. In both cases, too, you try to set up operations in a nice secluded spot, where you won’t get laughed at for your mechanical eccentricities (in the case of sugarin’) or arrested (in the case of moonshining).

In an earlier edition of this book, I spent a good deal of time describing, with pictures, some of the more ingenious contraptions being used for boiling down maple sap in the backyard, dealing less thoroughly with other important aspects of backyard sugarin’—like when and how to tap what kinds of maples, and some of the intricacies of boiling down sap without professional equipment. This time around I’m going to try to take the reader through the whole process, step by step, but still emphasizing, each step of the way, how you can get the job done without it costing an arm and a leg.

I am greatly indebted to my wife Louise, who, as I mentioned earlier, was responsible for getting me into backyard sugarin’ through her gentle persistence about my not boiling on the kitchen stove, to the several backyard operators who so modestly allowed their sugarin’ operations to be photographed, and of course to Dan Wolf, who has captured so well in photographs the essence of the backyard sugarin’ industry.

Cement block, the backbone of backyard sugarin’