Chapter 3

Character and plot

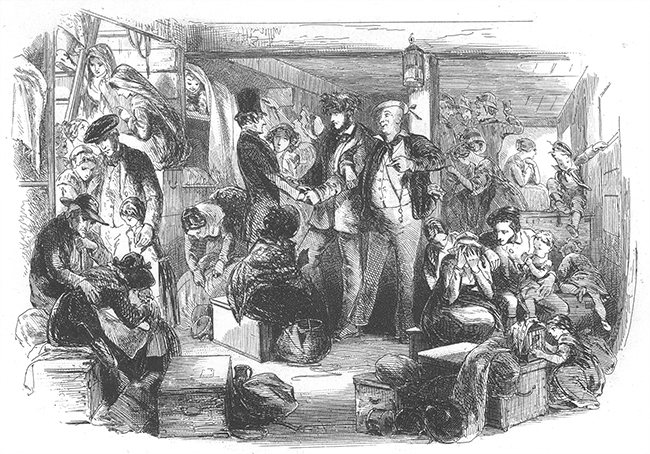

Characters are what Dickens is famous for. They crowd and flock through his novels—roughly 2,000 named characters, and multitudes more unnamed. The original illustrations by George Cruikshank and Hablot K. Browne (‘Phiz’), crammed with people, convey the sense of plenitude (see Figure 4). Many Dickens characters have achieved the fictional gold standard of life beyond the page, populating the empire of the collective imaginary. ‘Dickens excelled in character,’ wrote T. S. Eliot in his essay on Wilkie Collins and Dickens; ‘in the creation of characters of greater intensity than human beings’. On the other hand, Dickens’s characterization has been targeted for criticism, as have his plots. His characters are condemned as caricatures with no inner life, his plots as improbable and impossible to follow.

4. ‘The Emigrants’, David Copperfield, chapter 57, by Hablot K. Browne, Dickens’s principal illustrator over many years. ‘No other illustrator’, wrote G. K. Chesterton, ‘ever breathed the true Dickens atmosphere.’

Names, bodies, clothes

Dickens seems to have started his characters from the outside and the label on the outside, with names. As with everything else, so with names: Dickens never just does one thing. Puns, jokes, onomatopoeia, metonymy, satire, suggestiveness from lightest to heaviest. Mr M‘Choakumchild in Hard Times is the dry fact-obsessed schoolmaster, Wackford Squeers in Nicholas Nickleby the cruel one. Ebenezer Scrooge and Arthur Gride are misers, Sir Leicester Dedlock a representative of moribund aristocracy. The death bell already knells in Little Nell’s name. ‘Much deliberation’ went into the choice, according to Forster, listing some of the surnames Dickens considered—Sweezleden, Sweezleback, Sweezlewag, Chuzzletoe, Chuzzleboy, Chubblewig, Chuzzlewig—before settling on Chuzzlewit. Dickens described his mind ‘running, like a high sea, on names—not satisfied yet, though’, as Thomas Mag, David Mag, Wellbury, Flowerbury, Magbury, Copperboy, Topflower, and Copperstone all precede David Copperfield. Where the Chuzzlewit candidates are outrageous and comic, the Copperfield variants point to flowers, wells, things buried: the psychological terrain for a novel about memory. Dickens’s names are at the eccentric end of the individuality spectrum, and individuality is the point. Names too similar to each other do not augur well. In Bleak House Lord Coodle, Sir Thomas Doodle, and the Duke of Foodle, Buffy, Cuffy, and Duffy all belong to the same stultifying political cabal, stuck together in rhyming impasse.

What Dickens likes best is riffing on his own name. In his letters he is Dick. ‘On this day two and thirty years ago, the planet Dick appeared on the horizon’ runs an invitation to one of his birthday parties. He cuts himself off in the middle of a long letter, ‘as if there were no undone number, and no undone Dick!’ His novels take his name to ring the changes on what might have been his fate. In Oliver Twist Dick is the weakly child Oliver leaves behind him at the baby-farm; Charley Bates is the Dodger’s cheeky chum (punningly referred to as Master Bates), and the Dodger’s surname Dawkins not so far away from Dickens. In The Old Curiosity Shop Dick Swiveller is a lively young legal clerk, while Charley in Bleak House is an orphaned 13-year-old girl, labouring as a washerwoman to support her siblings. Less sympathetic is prentice-teacher Charley in Our Mutual Friend, not above exploiting his sister to get on in the world. Mr Dick in David Copperfield is a sort of holy fool obsessed by King Charles the First’s head. Dickens was apparently ‘much startled’ when Forster pointed out the initials were ‘but his own reversed’ for David Copperfield. ‘Why else, he said, should I so obstinately have kept to that name when once it turned up?’—in this novel mirroring his own experiences.

From names to bodies: the visual was crucial. All the novels apart from Hard Times and Great Expectations originally appeared with illustrations. Hablot K. Browne was Dickens’s principal illustrator, but many others, some very distinguished, were also called upon: in the early years George Cruikshank, Robert Seymour, Robert Buss, and George Cattermole, and for the lavish Christmas books John Leech, Richard Doyle, John Tenniel, Daniel Maclise, Edwin Landseer, Clarkson Stanfield, and Frank Stone. Samuel Palmer provided the illustrations for Pictures from Italy, and for his last two novels Dickens turned to a younger generation of artists: Marcus Stone, Charles Collins, and Luke Fildes. Dickens liked to work closely with his illustrators, and was attentive to the minutest detail and gesture. ‘Don’t have Lord Decimus’s hand put out,’ he wrote to Browne about a very minor character in Little Dorrit; ‘because that looks condescending; and I want him to be upright, stiff, unmixable with mere mortality.’

For Dickens, the body cannot choose but signal. The ‘much flushed’ magistrate Mr Fang in Oliver Twist, for example: ‘If he were really not in the habit of drinking rather more than was exactly good for him, he might have brought an action against his countenance for libel, and have recovered heavy damages’ (chapter 11). Madame Defarge’s strong features and ‘darkly defined eyebrows’ do not bode well in A Tale of Two Cities (book I, chapter 5). Nor do Hortense’s ‘feline mouth and general uncomfortable tightness of face, rendering the jaws too eager and the skull too prominent’ in Bleak House (chapter 12). Mrs Plornish’s introduction of her husband, plasterer and former bankrupt, to Arthur Clennam in Little Dorrit comes after a brief description: ‘A smooth-cheeked, fresh-colored, sandy-whiskered man of thirty. Long in the legs, yielding at the knees, foolish in the face, flannel-jacketed, lime-whitened. “This is Plornish, sir” ’ (book I, chapter 12). After the check list which ranges from facial features to yielding knees and back to ‘foolish in the face’, Mrs Plornish’s simple words act as summary and presentation to the reader: this is Plornish, we feel we know who Mr Plornish is. Faces can easily convey more than one message, such as the landlady Mrs Todgers in Martin Chuzzlewit, ‘with affection beaming in one eye, and calculation shining out of the other’ (chapter 8). People who do not want to be read have to keep their faces averted, as do many young women who feel threatened. But readability is usually a sign of worth, and inscrutable characters like lawyer Tulkinghorn in Bleak House are not to be trusted.

Clothes, like faces, are the first thing we see on meeting someone, and they always set Dickens’s imagination going. The early Boz sketch ‘Meditations in Monmouth-street’ celebrates the second-hand clothes for sale in the street which beget ‘meditations’, ‘speculating’, ‘conjuring up’, and ‘revery’. The narrator fills the empty clothes with bodies so that they come to vigorous life:

whole rows of coats have started from their pegs, and buttoned up, of their own accord, round the waists of imaginary wearers; lines of trousers have jumped down to meet them; waistcoats have almost burst with anxiety to put themselves on; and half an acre of shoes have suddenly found feet to fit them, and gone stumping down the street.

The clothes march through space and then time, with a consecutive narrative for some suits which Dickens decides all belonged to the same man at different periods. ‘There was the man’s whole life written as legibly on those clothes, as if we had his autobiography engrossed on parchment before us.’ The story starts with the small sweet-eating child—‘the numerous smears of some sticky substance about the pockets, and just below the chin’—and proceeds through message-lad’s long-worn suit through ‘smart but slovenly’ man-about-town to end inevitably with prison garb and disgrace.

Dickens’s characters can make their clothes speak forcibly. In Great Expectations the jilted Miss Havisham, still clad in the wedding dress she should have been married in years ago, is a famous example of statement clothes, while Pip’s grudging sister also expresses herself sartorially. She ‘almost always wore a coarse apron, fastened over her figure behind with two loops, and having a square impregnable bib in front, that was stuck full of pins and needles’. These sometimes get into the bread she cuts and subsequently ‘into our mouths’ (chapter 2). When her husband, Joe the blacksmith, visits Pip newly ‘gentle-folked’—‘Joe considered a little before he discovered this word’—he insists on balancing his hat so precariously on the edge of Pip’s mantel-piece that it keeps toppling off, being restored, toppling off again, an apt analogue for the relations between him and Pip at this point (chapter 27). More agreeably, nautical Captain Cuttle in Dombey and Son has such a large shirt collar ‘that it looked like a small sail’ (chapter 4).

Some characters, the performers, deliberately use bodies, clothes, and names to send signals—practices swiftly seen through by the narrator’s observing eye. Mr Mantalini (‘originally Muntle’), the extravagantly dressed confidence trickster in Nicholas Nickleby,

had whiskers and a moustache, both dyed black and gracefully curled. … He had married on his whiskers; upon which property he had previously subsisted, in a genteel manner, for some years; and which he had recently improved, after patient cultivation by the addition of a moustache, which promised to secure him an easy independence.

(chapter 10)

Another fake, Mr Turveydrop in Bleak House, primps himself up elaborately in order to sponge off his good-natured son:

He was a fat old gentleman with a false complexion, false teeth, false whiskers, and a wig. … He was pinched in, and swelled out, and got up, and strapped down, as much as he could possibly bear. He had such a neck-cloth on (puffing his very eyes out of their natural shape), and his chin and even his ears so sunk into it, that it seemed as though he must inevitably double up, if it were cast loose. … He had a cane, he had an eye-glass, he had a snuff-box, he had rings, he had wristbands, he had everything but any touch of nature; he was not like youth, he was not like age, he was like nothing in the world but a model of Deportment.

(chapter 14)

More appealing is the transparent dress-code devised by Sairey Gamp, layer-out of corpses in Martin Chuzzlewit:

She wore a very rusty black gown, rather the worse for snuff, and a shawl and bonnet to correspond. In these dilapidated articles of dress she had, on principle, arrayed herself, time out of mind, on such occasions as the present; for they at once expressed a decent amount of veneration for the deceased, and invited the next of kin to present her with a fresher suit of weeds: an appeal so frequently successful, that the very fetch and ghost of Mrs. Gamp, bonnet and all, might be seen hanging up, any hour in the day, in at least a dozen of the second-hand clothes shops about Holborn.

(chapter 19)

People and objects

‘I think it is my infirmity to fancy or perceive relations in things which are not apparent generally,’ Dickens wrote to Bulwer-Lytton in 1865. Even a standard thank-you letter can catch the infection. ‘A thousand thanks for the noble turkey’ ran one to Miss Coutts in 1841. ‘I thought it was an infant, sent here by mistake, when it was brought in. It looked so like a fine baby.’ The ‘relations’ between animate and inanimate, and the traffic between them, intrigued him. The Dickensian turn twists people into objects, objects into people, people into animals. He delights in connections and disconnections. Where, for instance, do bodies begin or end? How fitting that the earliest surviving letter from him as a 13-year-old schoolboy has a joke about a wooden leg—a lifelong source of amusement. Some years later, the gentleman at the Britannia Saloon advertised to dance the Highland Fling ‘his wooden leg highly ornamented with rosettes’ was just the thing for an evening out with friends.

Bodies and bits, and bodies in bits: Dickens’s eye takes a ghoulish snapshot of Mr Pecksniff in Martin Chuzzlewit eavesdropping in church, ‘Looking like the small end of a guillotined man, with his chin on a level with the top of the pew’ (chapter 31). Mr Jingle in Pickwick Papers also relishes heads without bodies in his story prompted by the banal instruction to mind your head as the coach goes under a low archway. ‘ “Terrible place—dangerous work—other day—five children—mother—tall lady, eating sandwiches—forgot the arch—crash—knock—children look round—mother’s head off—sandwich in her hand—no mouth to put it in” ’ (chapter 2). The boundaries of the body are not always where you expect. In Hard Times the dying Mrs Gradgrind, who has never been much more than a ‘thin, white, pink-eyed bundle of shawls’, is asked if she is in pain. ‘“I think there’s a pain somewhere in the room”, said Mrs Gradgrind, “but I couldn’t positively say that I have got it.”’ (book II, chapter 9).

Dickens’s use of synecdoche can distil character to one body-part. For the clerk Mr Wemmick in Great Expectations it is his ‘post-office of a mouth’ in which he pops pieces of biscuit as if posting them (chapter 24). For villainous Uriah Heep in David Copperfield it is his clammy hands, obsequiously rubbed together. In Little Dorrit, trophy-wife Mrs Merdle is introduced as her bosom. ‘It was not a bosom to repose upon, but it was a capital bosom to hang jewels upon.’ Thereafter ‘The bosom, moving in Society with the jewels displayed upon it’ (book I, chapter 21) is how Mrs Merdle progresses majestically through the novel.

Blurring the boundaries between animate and inanimate sometimes looks like an urban tendency. Houses and streets are anthropomorphized, like the Six Jolly Fellowship Porters tavern in Our Mutual Friend, which leans lopsidedly over the river ‘but seemed to have got into the condition of a faint-hearted diver who has paused so long on the brink that he will never go in at all’ (book I, chapter 6), or the ‘dowager old chimneys’ which ‘twirled their cowls and fluttered their smoke, rather as if they were bridling, and fanning themselves, and looking on in a state of airy surprise’ (book II, chapter 5). Other streets can have the opposite effect. The mews behind the ‘dismal grandeur’ of the Dedlocks’ mansion in Bleak House ‘have a dry and massive appearance, as if they were reserved to stable the stone chargers of noble statues’ (chapter 48).

Dickens associates movement with life; for him it is in movement that we see the life-force in action. Much as he admired the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition in 1857, he told his friend Macready, he thought people wanted ‘more amusement, and particularly (as it strikes me) something in motion, though it were only a twisting fountain’. The owners of bodies which have got stuck are in trouble, like Miss Havisham in Great Expectations or Mrs Clennam in Little Dorrit. Bits of bodies which move when they should not can be comic, like Silas Wegg’s wooden leg in Our Mutual Friend, elevating itself lewdly at the mention of buried treasure. One of the hallmarks of the Household Words house style was to imbue things with life, so that the commodities of Victorian consumer culture clamour for our attention with life-stories of their own.

Externalized psychology

Dickens often gives us the inner by means of the outer. His psychology, wrote Viennese novelist Stefan Zweig, ‘began with the visible; he gained his insight into character by observation of the exterior’, his eye ‘rendered acute by a superlative imagination’. Gesture and behaviour are freighted with meaning. Miss Tox snips and clips her pot plants ‘with microscopic industry’ as she learns that her hopes of becoming the second Mrs Dombey have come to nothing (chapter 29). In Hard Times, Louisa Gradgrind, when kissed by the odious Mr Bounderby, rubs her cheek ‘with her handkerchief, until it was burning red’ (book I, chapter 6). The school-teacher Bradley Headstone in Our Mutual Friend acknowledges that he has finally been trapped in his gesture of slowly wiping his name out on the blackboard (book IV, chapter 15). Tiny moments can betray the inner man, like the ‘sharp involuntary glance’ which the starving Jingle ‘cast at a small piece of raw loin of mutton’ and told Mr Pickwick more of Jingle’s ‘reduced state than two hours’ explanation could have done’ (chapter 42).

Possessions speak volumes. David Copperfield’s step-aunt Miss Murdstone keeps her ‘hard steel purse … in a very jail of a bag which hung upon her arm by heavy chains, and shut up like a bite’ (chapter 4). Mrs Pipchin, the ‘ogress and child-queller’ with whom young Paul Dombey boards, collects grotesque plants ‘like hairy serpents; another specimen shooting out broad claws, like a green lobster; several creeping vegetables, possessed of sticky and adhesive leaves’ (chapter 8). In Bleak House, the lawyer Mr Vholes shares his office with legal blue bags ‘hastily stuffed, out of all regularity of form, as the larger sort of serpents are in their first gorged state’ (chapter 39).

‘If he could give us their psychological character’, wrote George Eliot of Dickens in 1856, ‘their conceptions of life, and their emotions—with the same truth as their idiom and manner, his books would be the greatest contribution Art has ever made to the awakening of social sympathies.’ But if there is little extended psychological analysis, there is, for example, an assured understanding of dependency culture in Uriah Heep—‘ “We was to be umble to this person, and umble to that … and abase ourselves before our betters” ’ (chapter 39)—and its logical consequences. Unrealistic many of Dickens’s eccentrics and grotesques may be, but their oddities can be the markers of internal damage and strain. And some of his characters do think deeply, their complex thought processes intricately traced by their author. Arthur Clennam in Little Dorrit suspects a guilty secret in his parents’ past, and cannot handle the unwelcome thoughts which the suspicion might uncover.

As though a criminal should be chained in a stationary boat on a deep clear river, condemned, whatever countless leagues of water flowed past him, always to see the body of the fellow creature he had drowned lying at the bottom, immovable, and unchangeable, except as the eddies made it broad or long, now expanding, now contracting its terrible lineaments; so Arthur, below the shifting current of transparent thoughts and fancies which were gone and succeeded by others as soon as come, saw, steady and dark, and not to be stirred from its place, the one subject that he endeavoured with all his might to rid himself of, and that he could not fly from.

(book II, chapter 23)

Arthur condemned to the return of the repressed, long before Freud.

More submerged creatures haunt the depths in Dombey and Son, to give shape to young Florence Dombey’s growing dread of her father’s employee Mr Carker and ‘the web he was gradually winding about her’. Beset by ‘wonder and uneasiness’ she deliberately tries to remember him more distinctly in order to reduce him ‘to the level of a real personage’, but it does not work. Is her antipathy to Carker something wrong with her, she thinks; could that something be to do with sex? That is something which the innocent Florence cannot know about, and Dickens reminds us she lacks the ‘art and knowledge of the world’ to deal with Carker. But she can have dread, and Dickens ends the passage with a brilliant image of Carker underwater, simultaneously inside and outside Florence:

Thus, with no one to advise her—for she could advise with no one without seeming to complain against him—gentle Florence tossed on an uneasy sea of doubt and hope; and Mr Carker, like a scaly monster of the deep, swam down below, and kept his shining eye upon her.

(chapter 28)

Angels and villains

Dickens’s good characters are too good, his heroines are bland blanks: critics have complained that he cannot construct convincingly adult young women. He seems entranced by juvenile house-keeping. In Martin Chuzzlewit, Ruth Pinch makes a beef-steak pudding: ‘Such a busy little woman’, it was a ‘perfect treat’ for her brother Tom, and for us too Dickens implies,

to see her with her brows knit, and her rosy lips pursed up, kneading away at the crust, rolling it out, cutting it up into strips, lining the basin with it, shaving it off fine round the rim; chopping up the steak into small pieces,

and so on and on through all the ingredients (except suet; reprimanded by a reader, Dickens added it in a subsequent number) to the predictably delicious result (chapter 39).

While the saccharine is undeniable, it is worth saying that Dickens does give us complex female characters, often with elements of sexuality. Rosa Dartle in David Copperfield, Miss Wade in Little Dorrit, and Lady Dedlock in Bleak House all have back stories and a sexual history. Estella flushes with excitement in Great Expectations as she watches Pip and Herbert fight, and invites Pip to kiss her. Nancy in Oliver Twist lives on into our times as the tart with a heart, the victim of her pimp lover Bill Sikes. But Dickens gives her more inventiveness than that stereotype suggests. Forced by her lowlife companions into a plot to extricate Oliver from his middle-class patrons, she dresses up respectably with props provided by Fagin, and eventually takes to her role with zest:

‘Oh, my brother! My poor, dear, sweet, innocent little brother!’ exclaimed Nancy, bursting into tears, and wringing the little basket and the street-door key in an agony of distress. ‘What has become of him! Where have they taken him to! Oh, do have pity, and tell me what’s been done with the dear boy, gentlemen; do, gentlemen, if you please, gentlemen!’

Having uttered these words in a most lamentable and heart-broken tone: to the immeasurable delight of her hearers: Miss Nancy paused, winked to the company, nodded smilingly round, and disappeared.

(chapter 13)

Dickens can never resist performance. In our enjoyment and admiration for Dodger and Nancy, and their swagger and verve, we overlook their designs on Oliver’s innocent young soul.

The self-deprecating angel flitting through the fiction owes much to Mary Hogarth. Her first reincarnation as Rose Maylie in Oliver Twist sickens and nearly dies, but recovers. She reappears as Little Dorrit, as Agnes Wickfield in David Copperfield, and as Esther Summerson in Bleak House. Angels they may be, but they are also damaged and vulnerable. Rose feels the ‘blight upon my name’ of illegitimacy (chapter 35). Agnes has an alcoholic father and is prey to Uriah Heep’s sexual machinations. Little Dorrit is mercilessly exploited by her family. Esther is illegitimate, her self-esteem squashed by her punitive godmother. ‘“It would have been far better, little Esther,”’ she tells her on her birthday, ‘“that you had had no birthday; that you had never been born!”’ (chapter 3).

Out of these potential victims Dickens fashions his heroine material. They can be surprisingly resourceful. Agnes runs a school to make ends meet; Esther is an efficient housekeeper; Little Dorrit finds training and employment for her elder siblings and herself. This competence combines with the magical ability to walk the streets of London undefiled, to face danger and be unharmed. Realism is fused with allegory, romance, religious parable: Dickens never does just one thing. In Dombey and Son, little Florence is lost on the streets of London and is rescued by gallant Walter Gay, who replaces her shoe ‘as the prince in the story might have fitted Cinderella’s slipper on’ (chapter 6). Fairy-tale in Thames-street, imaginary characters in the real docks of London.

On the other hand, Dickens’s villains have had a good press. His fascination with the criminal and the pathological has long been recognized. Dostoevsky was one of the first novelists to take the lead from Dickens, and in our own culture the fascination shows no sign of abating. Dickens revels in putting us inside Fagin during his trial and beside him in the condemned cell. Violent Bill Sikes starts as a growling thug seen from the outside; but having murdered Nancy his guilt endows him with interiority, and Dickens devotes a whole chapter to ‘The Flight of Sikes’. In slow motion and close focus he tracks his every move. The terror is in the detail, as Sikes tries to remove the evidence—‘there were spots that would not be removed, but he cut the pieces out, and burnt them’—and escape from the horrifying apparition of the murdered woman. But it pursues him from London, ‘that morning’s ghastly figure following at his heels … its garments rustling in the leaves’, and the thug disintegrates before our eyes. Then, in an extraordinary scene, he comes across some burning buildings and galvanizes into life.

Hither and thither he dived that night: now working at the pumps, and now hurrying through the smoke and flame, but never ceasing to engage himself wherever noise and men were thickest … in every part of that great fire was he; but he bore a charmed life.

(chapter 48)

Those fires inside himself which he cannot put out: the mania of guilt engages Dickens more than the morality. The little room into which Jonas Chuzzlewit locks himself before and after he commits murder is ‘a blotched, stained, mouldering room, like a vault; and there were water-pipes running through it, which at unexpected times in the night, when other things were quiet, clicked and gurgled suddenly, as if they were choking’. It is this squeezed gothic kennel rather than the scene of his crime which frightens Jonas; ‘his hideous secret was shut up in the room, and all its terrors were there’ (chapter 47).

When angels and villains meet, Dickens favours non-realism. The Old Curiosity Shop has one of his most egregious villains and one of his most angelic heroines. Little Nell has been the best-loved and most mocked character in English literature. Readers in New York are reported to have lined the quaysides agog for the next instalment arriving from London, shouting ‘Is Little Nell still alive?’ Her death came to be the classic type of Victorian sentimentality, and was thus soon reviled. Oscar Wilde’s view was that one would need a heart of stone to read the death of little Nell without laughing. The critic John Ruskin accused Dickens of killing her for the market as a butcher kills a lamb, but although Dickens knew it was good for business he was nevertheless sincere and counted himself among the weepers. ‘Dear Mary’ dies again, he told Forster as he put the finishing touches to the novel—‘such a very painful thing to me’; on the other hand he was also out partying till after five in the morning.

Although Nell is more active—and laughs more—than her critics may remember, on one level they are right. She staggers under the weight of being an emblem of purity. The first scene introduces her to us as a child in a fairy-tale, making her solitary way through the streets of night-time London. Later, leading her aged grandfather away from danger, she is evoked through archaic language and the novel’s many references to The Pilgrim’s Progress and Shakespeare.

In symmetrical opposition to this allegory of goodness is the dwarfish Daniel Quilp. Pantomime villain and comic monster, he pops up ‘like an evil spirit’ when least expected. He terrorizes Nell, pursuing her even to her bedroom, where he bounces on her bed. Kissing her lasciviously—‘“What a nice kiss that was—just upon the rosy part”’—he invites her to be ‘“my number two”’ (chapter 6). His energy and appetite are demonic: ‘he ate hard eggs, shell and all, devoured gigantic prawns with the heads and tails on, chewed tobacco and water-cresses at the same time and with extraordinary greediness’ (chapter 5). ‘“I hate your virtuous people!”’ he crows as he downs pints of boiling rum (chapter 48); and ‘“Where I hate, I bite”’ (chapter 67). Quilp is ‘a perpetual nightmare to the child’ (chapter 29), but more terrifying still is the threat from within. ‘Immeasurably worse, and far more dreadful’ than Punch-like Quilp is her own grandfather. By day a ‘harmless fond old man’ (Lear set against Quilp’s Richard III), by night he is a compulsive gambler, the horrible unnameable ‘dark form’ creeping into Nell’s bedroom, invading her bed in search of money, ‘groping its way with noiseless hands … the breath so near her pillow, that she shrunk back into it, lest those wandering hands should light upon her face’ (chapter 30).

This early novel represents Dickens’s modes of characterization at their most extreme and expressive. But if the later novels are more realistic they draw upon the same cast of monsters and the same clashes between good and evil. The father who exploits his daughter reappears in William Dorrit trying to persuade his daughter Amy to look kindly on the jailer’s son in order that life will be easier in prison for him. And running throughout the novels from first to last is the Dickens signature of superfluity—that super-abundance of characters on the periphery who may appear once or who never speak: right up to the boatman Lobley in the last number of the unfinished Edwin Drood, who ‘danced the tight rope the whole length of the boat’ just for the pleasure of it.

Improbable plots

Dickens was sensitive to charges that his plots were far-fetched and implausible. His Postscript to Our Mutual Friend tackles head-on the ‘odd disposition in this country to dispute as improbable in fiction, what are the commonest experiences in fact’. His customary defence is to cite evidence from current events that such things are so. In his Preface to Bleak House he claims that his treatment of the Court of Chancery is ‘substantially true, and within the truth’. He likes to cite authorities: The Lancet medical journal for his portrayal of the Poor Law in Our Mutual Friend, and a parade of abstruse historians for the outrageous spontaneous combustion plot-line in Bleak House.

Dickens was being disingenuous. What critics mainly objected to are the tortuous wills unravelled in the last chapter, the fortuitous arrivals of long-lost relations. In his book on Dickens, admirer though he was, George Gissing felt compelled to ‘speak of the sin, most gross, most palpable, which Dickens everywhere commits in his abuse of coincidence’. Dickens himself did not see it as abuse. ‘On the coincidences, resemblances and surprises of life’, wrote Forster in his biography, ‘Dickens liked especially to dwell, and few things moved his fancy so pleasantly. The world, he would say, was so much smaller than we thought it; we were all so connected by fate without knowing it.’

Benevolent fate seems to be at work when Nicholas Nickleby meets his future benefactor in the street. Here is fortune smiling at last on the struggling young hero. Nicholas and Mr Cheeryble could easily have met inside the employment agency they are standing outside; after all, one of them is looking for employment and the other has a vacancy. But see how providential it is, Dickens’s coincidence plot seems to be saying, that good employers and good employees should bump into each other on the street.

The chance meetings of Bleak House show a much less kindly fate at work. Here the ‘connexion’ between the rich and poor characters is central to the plot and is foregrounded as an explicit issue. ‘What connexion’, the narrator asks, ‘can there have been between many people in the innumerable histories of this world, who, from opposite sides of great gulfs, have, nevertheless, been very curiously brought together!’ (chapter 16). The answer is provided by the plot, which puts Dickens’s social and moral preoccupations into action.

Dickens also needs plot for suspense, that third ingredient of the tripartite imperative of Victorian popular fiction—‘Make ’em laugh, make ’em cry, make ’em wait!’—which he structured into his method of publication from the start. Serial form builds waiting and suspense into the meaning of the novel and makes them a crucial part of the reading experience, which is why this book has tried to eschew plot spoilers. In chapter 49 of David Copperfield, ‘I am Involved in Mystery’, Mr Micawber promises to tell David his ‘“inviolable secret”’ about Uriah Heep ‘“this day week”’; the original readers would have to wait a month. Readers had to wait a week to learn the identity of the man lunging through the bushes at pretty Dolly Varden at the end of chapter 20 of Barnaby Rudge, as they would to find out the import of the last words of chapter 44 of Great Expectations, Mr Wemmick’s terse note to Pip, ‘don’t go home’. While such cliff-hangers are not as common as Dickens’s reputation for them suggests, he does expect his readers to be able to wait and to remember, across long time-spans and with little prompting. The first readers of Our Mutual Friend heard of two characters called Jacob Kibble and Job Potterson in the first number in May 1864, then no more about them until January 1865, and then nothing again until November. The first part of Little Dorrit ends with a reference to an iron box which does not reappear until the last number a year and a half later. Kibble, Potterson, and the iron box are all plot-functional, planted and held in readiness by the forward-thinking author.

As with character so with form, Dickens enjoys the mash-up of genre. He mixes up stark realism, broad satire, romance, fable, fairy-tale, farce, and tragedy, playing them against each other. Early in his career he chose a telling analogy for his methodology. ‘It is the custom on the stage’, he says in Oliver Twist, ‘in all good, murderous melodramas: to present the tragic and the comic scenes, in as regular alternation, as the layers of red and white in a side of streaky, well-cured bacon’ (chapter 17). One moment the hero is ‘weighed down by fetters and misfortunes’, the next we are enjoying a comic song. Juxtaposition is all. These ‘sudden shiftings of the scene’ are justified, he says, ‘from well-spread boards to death-beds’, because such ‘transitions’ happen ‘in real life’ too. That was his defence, but more interesting is his appeal to melodrama, that exaggerated, expressive, moral, and above all popular cultural form.

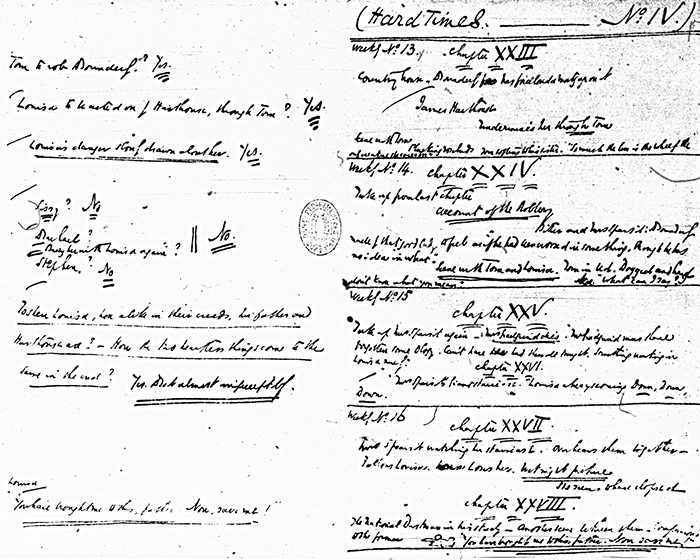

To begin with improvisation was the spur, and the novels of the 1830s and early 1840s can seem as if they might sprawl indefinitely, with weak and implausible plot lines. They look back to the picaresque novels of Smollett and Fielding, the historical novels of Walter Scott. With Dombey and Son (1846–8) came a decisive change. From then on the novels would be more carefully planned, and Dickens kept working notes and memorandums (see Figure 5). ‘I work slowly and with great care, and never give way to my invention recklessly, but constantly restrain it,’ he told Bulwer-Lytton in 1865.

5. Manuscript of Dickens’s working notes for Hard Times: left-hand side for planning and progress so far, right-hand side for division of content into chapters, as well as weekly and monthly parts.

He wanted it every which way: the excitements of protracted publication, with his readers bound to him and living with his characters for a year and a half at a time; but he also wanted to draw his readers’ attention to what in the Preface to Little Dorrit he called the merits of the whole.

As it is not unreasonable to suppose that I may have held its various threads with a more continuous attention than any one else can have given to them during its desultory publication, it is not unreasonable to ask that the weaving may be looked at in its completed state, and with the pattern finished.

The Postscript to Our Mutual Friend again refers to the ‘whole pattern which is always before the eyes of the story-weaver at his loom’. Both Preface and Postscript were written after their final monthly parts—thumping double numbers to reinforce the triumphant closure so long deferred that it deserves emphatic resolution, however forced and unlikely. That is the point of plot for Dickens: to link and connect, so that the lost and the random and the disparate will be brought together and given meaning, their places finally revealed in the ‘whole pattern’ of the universe of the book.