Telling the Story With Visuals

So you want to be a comic book storyteller. What does that mean?

Boiled down, it’s fairly simple. It means you have a job to do and that job is to tell the story. If you’re writing, drawing or writing and drawing, it doesn’t matter, your job is to tell a story and to do so effectively and in an entertaining way.

You have two priorities:

1 Communicate clearly to the reader.

2 Entertain the reader.

Nothing else matters.

COMMUNICATION: THE FIRST PRIORITY

Writers have to make sure that there is never a moment when the artist reading your script wonders what location he’s in, which characters are in the scene and who is talking with whom. Every descriptive line should communicate information that propels the characters through the story. Every line of dialogue must communicate one thing on the surface, and another thing beneath the surface—subtext is a necessity. For example, in The Empire Strikes Back, Han Solo is about to be put to death and the princess says to him, “I love you.” Solo’s response is, “I know.” The audience knows that what “I know” really means is “I love you, too.” Th at’s subtext. It’s the meaning beneath the words.

Writers have to know why characters have conversations in the locations they’re in. That location carries meaning. Are they in an office? Outside in the daylight? In a parking garage? Every decision carries a message.

Artists have to make sure that all the clarity the writer puts into the script makes it to the final page. If something is confusing to them in the script, it’s their job to make sure that it’s clear as day on the final drawn page.

If the panel descriptions leave artists room to add their own touches to the page, they have to do so knowing the impact their decisions carry. If they draw one of the two speakers in the conversation from an extreme low angle, they must do so knowing the effect that this camera angle carries. That speaker will appear large and strong. Should the figure appear this way? Perhaps, but perhaps not.

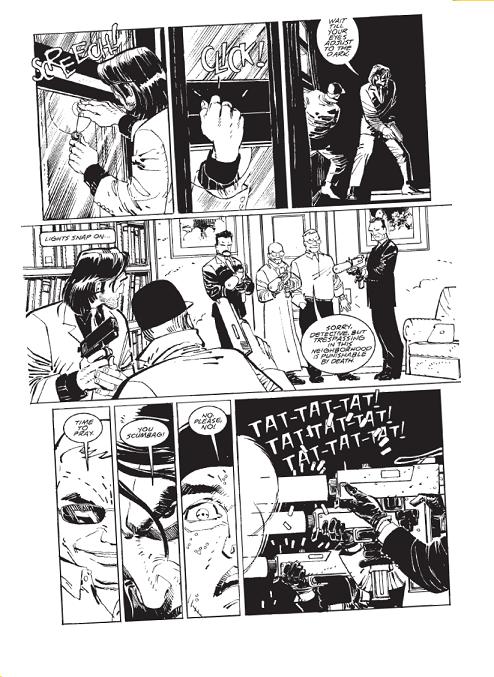

Showing Emotions

On this page by John Romita Jr., all actions flow properly. Before the two men can break into the building, they must unlock the window—the reader then feels surprised along with the characters to find that their foes are waiting for them.

The Gray Area #1: ©2005 John Romita, Jr. and Glen Brunswick. Used with permission.

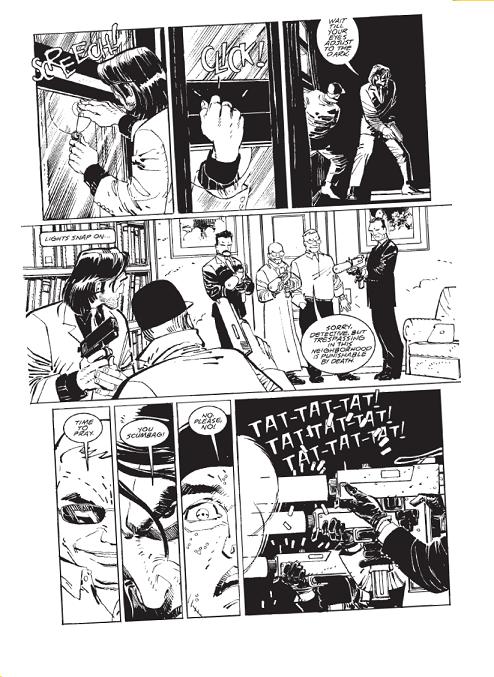

Sometimes, It’s Necessary to Establish Everything

Establishing shots are generally necessary in transitioning from one scene to the next. In this page, artist Mitch Breitweiser begins with a location establishing shot to give the reader a clear indication of where this scene takes place. In the second panel, notice the telephone pole behind the young man, again, establishing that he’s outside instead of inside the buildings shown.

Drax the Destroyer #3: ©2008 Marvel Characters, Inc. Used with permission.

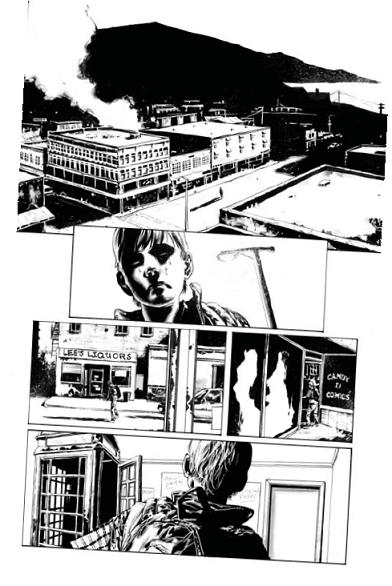

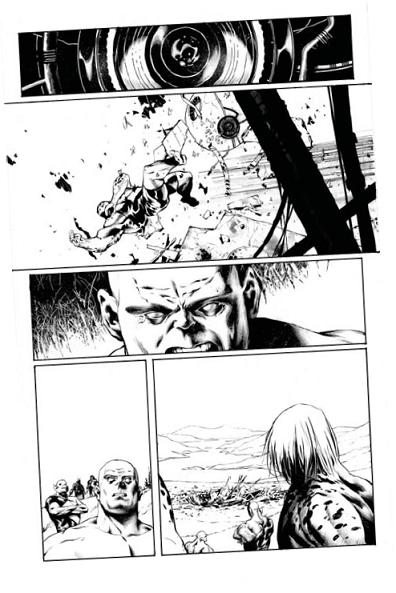

Sometimes, the Emotion Is More Important

In another page of Mitch’s, an establishing shot wasn’t called for. Instead, it was decided to go in for a close-up to accentuate the confusion caused by sudden action and then catch up the reader later on the page. That’s what was done here. The reader should be confused until panel 4, where Mitch pulls the camera back to establish the scene.

Drax the Destroyer #1: ©2008 Marvel Characters, Inc. Used with permission.

ENTERTAIN: THE SECOND PRIORITY

The second function of a storyteller is to entertain. Obviously, all comic readers would like to be entertained, but here’s the only rule: Never put entertainment before communication. Communicate the information that needs to come across, and then make it entertaining. Placing emphasis on entertaining rather than telling leads to failure.

I’m sure you can recall a time where you saw an amazing splash page that blew you away with how beautiful it was, but it also left you wondering how it related to the panels surrounding it. When this happens, the reader is pulled out of the story and the illusion is shattered.

Once the information—the storytelling— is down, writers and artists have to figure out how to communicate it in the most entertaining way possible. There is always a dramatic and appropriate way to illustrate a scene. It’s a fine line to balance on, and knowing how far to push comes with practice.

It Starts With Story

Always tell the story first, and then entertain. You’ll know the story is good when simply telling it is entertaining.

Do Nothing Lightly

Every decision made carries information and impact to the reader. So make every decision carefully.