There was a great uneasiness about the threat of bomber attack throughout most of Europe in the 1930s. Germany had attacked British cities during World War I using Zeppelins and bombers, and there was a widespread presumption that bomber attack against cities and factories would become a feature of future wars. There was particular concern that bomber attacks would include the use of chemical weapons. Popular novels and science fiction of the day depicted the apocalyptic horrors of gas attack against unprotected cities. The dilemma facing Germany was the extent of air defense needed both for active air defenses, such as fighter aircraft and anti-aircraft guns, as well as passive defenses, such as air-raid shelters for civilians and military personnel. Hitler and the Nazi Party were inclined towards offensive use of air power, which would presumably avoid the need for extensive and expensive air defense preparations, and so Germany’s early work in this field was less comprehensive than in Britain.

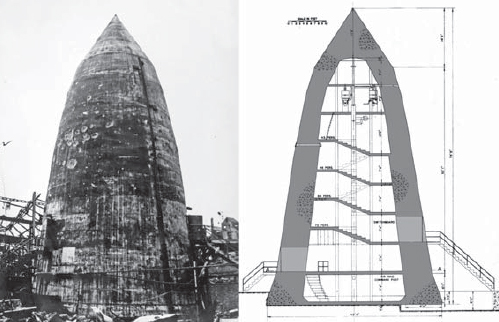

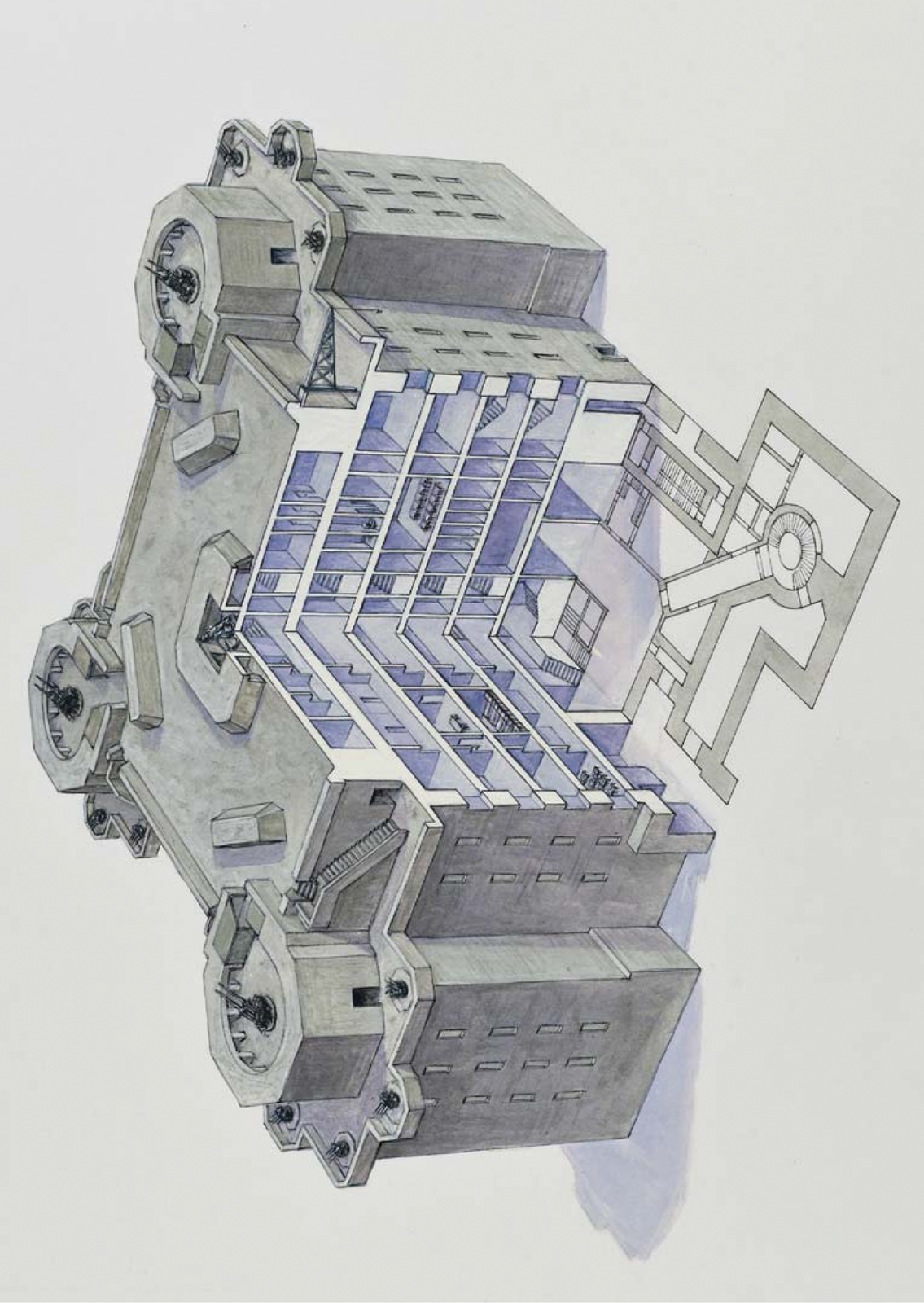

A battle-scarred Winkel tower in the ruins of the Gelsenkirchener Benzin synthetic fuel plant in Buer-Scholven. This particular plant was hit by 246 tons of bombs in the USAAF raid on October 30, 1944, and this airraid shelter was one of the few structures to survive. To the right is a scale cross-section of the Typ 1c tower showing the internal layout and prepared by a post-war US bombing survey team. (NARA)

During the 1920s, the German government took its first tentative steps towards organizing air-raid-protection services, mainly managed by the Ministry of the Interior through the police. Popular organizations such as the Deutsche Luftschutz-Liga (German Air Defense League) attempted to drum up popular support for a more vigorous defense effort. These early endeavours were intended to inform the general public about the air threat, to formulate plans for the construction of air-raid shelters and the manufacture of gas-masks, and to encourage voluntary public participation in air defense.

It was only after Hitler’s accession to power in 1933 that plans became more formal. In June 1933, the shadow Luftwaffe under Hermann Göring announced the formation of National Air Raid Protection League (Reichsluftschutzbund, or RLB). The RLB was organized on a regional basis by province (Landes), regions (Gaue), area (Kreis), and district (Orts) down through local leaders at block and building level. Overall military supervision of the air-raid protection effort was undertaken by a special inspectorate of the Führungsstab 1A of the Luftwaffe’s general staff, first located in Wannsee near Berlin, and later in Tangermunde. The air-raid protection law signed by Hitler in August 1935 made it a duty of all German citizens to participate in this program, and established the practice that there would be no government compensation for personal service. The government in Berlin gradually absorbed more control over the process, with Heinrich Himmler taking control of police work in air-raid protection after the summer of 1936 through the interior ministry. The first major decree on air-raid protection was released in May 1937 and broadly outlined the structure that would be in place throughout the war.

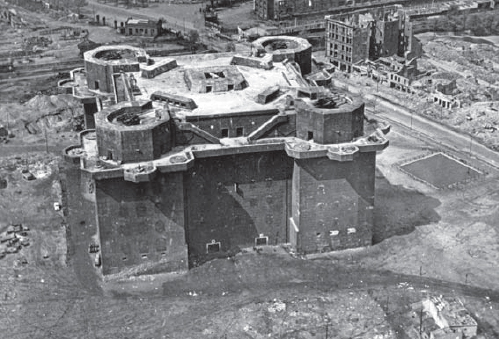

The Winkel towers proved very effective during the war. These two Typ 1c Winkel towers were located in the Focke-Wulf Werke plant in Bremen and as can be seen, the rest of the factory was completely devastated by Allied bombing raids but the towers remained largely intact. (NARA)

The Dietel tower adopted a neo-Romantic style patterned after medieval town gate-towers. This example, built in Darmstadt by Dyckerhoff & Widmann, was named after the famous “Red Baron” ace of World War I. It is still in existence, but now serves as the Mozart Digitalarkhiv. (NARA)

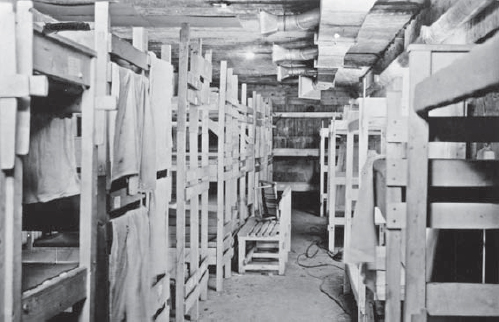

Enclosed air-raid trenches were one of the more common types of air-raid shelters built during the war. This particular example under construction in Cologne shows typical construction. As can be seen, the tunnel zig-zags to mitigate the blast effect should any one section of the structure be hit by a bomb. (NARA)

The 1937 decree formed the basis for subsequent air-raid-shelter policy. A Reichsgruppe Industrie was established to supervise the new Werkluftschutz (“industrial air-raid protection service”) and to encourage the construction of large shelters adjacent to factories and major commercial enterprises. The Erweiterselbschutz (“extended self-protection service”) was intended to manage air-raid protection for public and private buildings, as well as smaller commercial and industrial buildings. Air-raid-protection for homes and smaller private and public buildings was subordinated to the new Selbschutz (“self-defense service”), which encouraged the construction of private shelters and managed the air-raid warden system. The RLB was nominally a voluntary organization, but was in fact directed by the Nazi Party to encourage public participation in air-raid efforts. It eventually had a membership of 13 million and dues were used to inform and educate the general public about air-raid protection, as well as to provide minor items such as gas-masks to civilians too poor to purchase them. In general, the RLB’s function was primarily supervisory and educational, while the actual management of air-raid protection was overseen by the local police and fire services.

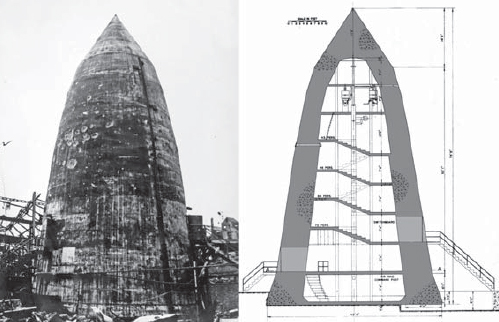

This illustration from a wartime Organization Todt handbook shows an elementary enclosed air-raid trench for 50 people made from wood rather than the preferred concrete or brick. The entrance is located at the left along with the gas-lock.

The Werkluftschutz industrial defense service initiated the first round of shelter construction in the late 1930s, especially for those areas deemed most vulnerable to air attack. This included major military plants, as well as other likely targets such as railway centres. Some sites that were exceptionally vulnerable to bomber attack, such as the naval base at Wilhelmshaven on the North Sea, saw the creation of bomb-proof shelters sooner than most other areas. Likewise, the Kriegsmarine began shelter construction at its most vulnerable ports such as Wilhelmshaven. However, large-scale construction of public air-raid shelters did not begin until after the start of the war.

Until the late 1930s, there were few systematic studies of modern air-raid shelters. The Institute for Air Defense Construction (IfBL, or Institut für Baulichen Luftschutz) was created under Prof. Dr. Theodor Kristen at the Technischen Hochschule Braunschweig to establish national standards for the construction of public air-raid shelters. Many of the early industrial shelters were designed by private engineering firms. The initial designs also addressed the need for gas protection, and a number of industrial firms began mass-production of gas-proof doors, filtration systems, and other components that could be incorporated into bomb shelters.

The government encouraged public institutions to create public air-raid shelters. One of the more unusual was this brick shelter erected within the Cologne cathedral to protect church staff and parishioners. (NARA)

The shock of the RAF raids on Berlin in August and September 1940 forced Hitler to initiate the Führer-Sofortprogramm (“emergency program”) on 10 October 1940 to protect Germany’s urban population with public air-raid shelters. The original scheme was to create about 6,000 bombproof bunkers, as well as many “splinter-proof” shelters for 35 million civilians in 92 cities. The original scheme would have required the fantastic total of 200 million cubic metres (260 million cubic yards) of concrete, about as much as the past two decades of civil construction. To put this in perspective, the Maginot Line had consumed 1.5 million cubic metres (2 million cubic yards) of concrete and the Atlantikwall program in France in 1942–44 used 17 million cubic metres (22 million cubic yards). Needless to say, these overly ambitious goals did not come close to realization.

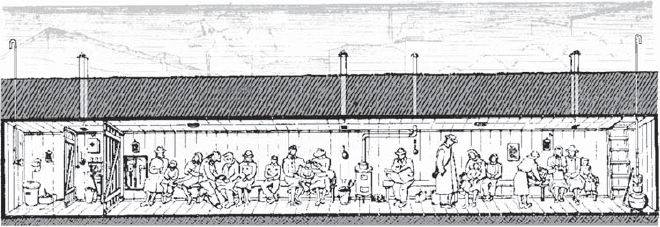

The early LS-Hochbunker had extensive fittings to make prolonged stays in the shelters as comfortable as possible. This is a view inside the Kaiserstrasse air-raid bunker in Krefeld and shows the typical configuration early in the war with wooden bunk beds. Once the shelters became overcrowded in 1944–45, the bunk-beds were removed to permit more people to take shelter in the bunkers. (NARA)

Due to the enormity of the work, the program was undertaken in three phases, with various cities categorized by priority (Luftschutz-Orten.1, .2, .3). The 70 highest priority cities were assigned to Phase 1 (Welle.1) with construction starting in November 1940 and the completion planned for November 1941. The program was managed by the Luftwaffe’s Inspektion.13 (L.In.13) led by Dr. Kurt Knipfer, and the construction was overseen by the Organization Todt (OT) paramilitary construction administration. Unlike military projects such as the Westwall or the later Atlantikwall, the Sofortprogramm was decentralized and there was less standardization of designs. Berlin delegated responsibility for much of the effort to local municipal governments and industry. The initial wave of the Sofortprogramm was intended to provide bomb-proof bunker shelters for about 5 percent of the population in the key cities, while the remainder of the population would have to make do with less robust Splittersichere (“splinter-proof”) shelters, which were primarily expedient adaptations of existing buildings and tunnels.

This LS-Hockbunker was designed by the architect Hans Schuhmacher and located on Kluckstrasse in Cologne. It has Schuhmacher’s distinctive “church bunker” style akin to those on Helenenwallstrasse and Marktstrasse. This particular bunker was hit with a large bomb that blew away about half of the ornamental roof. The roof acted as a burster slab, detonating the bomb before it hit the main roof. The bunker’s main horizontal roof was 1.4m (4.7ft) of steel-reinforced concrete. (NARA)

Another example of an LS-Hochbunker in Cologne with a decorative roof design and false dormers, located on Schnurgasse in Cologne. It was built in 1941–42 and could accommodate 1,080 people with 1,200 square metres (13,000 square feet) of floor space. (NARA)

By far the most common form of public shelter was the reinforced basement. These were classified at the lower “splinter-proof” standard since they could not withstand a direct bomb hit. In general, Luftschutz Kellar (“basement air-raid shelters”) were limited to a capacity of 50 to 100 persons. Most large apartment buildings had shelters created in their cellars. Where possible, the basements were upgraded with gas protection by sealing windows, adding an intermediate gas-lock room (Gasschleuse) at the main entrance, and incorporating a gas filter. Gas locks were small anterooms located in front of the main entrance door. They were intended to provide a space where civilians contaminated by chemical agents could be scrubbed clean before entering the shelter. The shelter entrance itself was protected by a gas-proof door.

An LS-Hochbunker near Goffartstraße in the Frankenburg section of Aachen during the fighting in the city in October 1944. Work on this structure began in January 1941 and it is typical of designs from this period that indulged in architectural detailing. It had a capacity for 2,000 people and was hit by a bomb at least once in late 1943 without casualties. It was used immediately after the war for refugee housing and after years of neglect, in 1987 it was converted into the Musikbunker for rock concerts. (NARA)

Another good example of an early LS-Hochbunker with extensive architectural detail including an ornamental roof and gables. Located on Sandweg in the Rochuspark suburbs of Cologne, it was designed by the architect Ernst Nolte and was completed in 1942. Local inhabitants used it as a refuge during the fighting on the western banks of the Rhine in March 1945, and some of the occupants have come out to wave a white flag during the approach of tanks of the 3rd Armored Division on March 5, 1945. After the war, it was converted into flats. (NARA)

Air-raid basements were reinforced with wood or steel beams to minimize the risk that they would be crushed if the building above collapsed during a bombing attack. German cities had a well-established construction practice of erecting fire-walls between buildings to prevent the spread of fire between buildings that shared common walls, but these walls could inadvertently trap civilians in the basement shelters. As a result, a program began to create passageways between buildings by cutting through the walls, and creating a more modest fire barrier with thinner brick that could be readily demolished if necessary for escape. Public shelters were very clearly marked by signs, and large white arrows were painted on walls near the entrance as an aid at night-time due to the black-out measures.

LS-Hochbunker design became increasingly frugal and simplified as the supply of concrete and labour became scarce. This LS-Hochbunker in Krefeld in March 1945 has a false roof to help it blend in better with the surrounding neighbourhood, but it is otherwise unadorned. (NARA)

This LS-Hochbunker in Krefeld in March 1945 is typical of bunkers built in 1943 in a simple style with little or no architectural detail. It had a capacity of about 10,000 people. The structure on the roof is part of the ventilation system. There were 11 large air-raid bunkers in the Krefeld area during the war. (NARA)

In general, new underground shelters were not the favoured design solution in Germany during the Sofortprogramm. However, in some places, such as factories where basements were not present, simple underground structures at shallow depths provided a quick and easy means to rapidly create air-raid shelters. These were called Deckungsgräben (“enclosed trenches”), or sometimes Splittersicheregräben (“splinter-protected trenches”). Variations on this design using circular concrete castings were called Röhrenbunker (“tube bunkers”). The enclosed trenches were strongly influenced by World War I trench fortification techniques. The crudest versions were simply trenches lined with wood, with a plank roof covered by a few feet of earth, although efforts were made to create more permanent and durable structures. By 1940, a number of German firms were offering prefabricated steel sections that could be used to create a metal-lined enclosed trench. However, industrial priorities for weapons production soon reduced the availability of steel for such projects. Organization Todt encouraged the use of prefabricated concrete sections, both for oval and rectangular structures. In addition, other forms of normal construction material such as brick and concrete block were widely used.

The enclosed trench shelters were generally designed to accommodate 100 to 500 persons, although the Organization Todt instruction book offered five standard designs for 15, 50, 100, 150 and 200 persons. The most common size was for 50 persons, and larger shelters were usually created by combining several 50-person sections. The standard practice was to avoid a single long tube, and either to stagger the sections with a slight off-set at the joint, or configure the sections in a zig-zag fashion or at right angles to one another. This was a standard tactic of World War I trench design and was intended to prevent the entire structure being destroyed if only one section was penetrated by a bomb.

Enclosed trench shelters were supposed to be completely buried for the best protection, but some were constructed in a partially submerged configuration, and others were built entirely on the surface with earth packed around them. These enclosed trench shelters were the second most common form of air-raid shelter in Germany during the war in terms of overall numbers. For example, the city of Osnabruck had about 650 air-raid shelters of which about 200 were concrete-enclosed trenches. Of these, about 90 were public shelters capable of accommodating about 13,000 people, while the remaining 110 were smaller privately built structures capable of housing about 2,150 people. The construction of enclosed trench shelters continued throughout the war since they required modest resources. Indeed, by 1944 when the construction of the large air-raid bunkers generally stopped due to the lack of material, enclosed-trench construction continued as an inexpensive, albeit less effective, alternative.

The primary type of bomb-proof shelter under the 1940 Sofortprogramm was the Luftschutz-Bunker (LS-Bunker). They were also called Hochbunker (“high bunker”) to distinguish them from the underground types. The intention of the 1940 Sofortprogramm was to provide bunker protection for about 5 percent of the city population, usually those in critical government and industrial positions and near government and industrial facilities. Pre-war studies of shelter design examined both underground and surface shelters and concluded that surface shelters were more economical to build than underground designs. The Brunswick IfBL also studied the relationship of bunker size and cost, and concluded that larger shelters were more economical. For example, a typical LS-Bunker design for 500 persons required 3 cubic metres (4 cubic yards) of concrete per person, while a design for 4,000 persons required only 1.8 cubic metres (3 cubic yards). The LS-Bunker program was controversial and it was opposed by some senior Luftwaffe technical officers who argued that it would be better to spread out the limited construction resources to give all civilians a certain level of protection rather than concentrating it on only a small number of places. Generalmajor W. Lindner, head of the technical division of the Luftwaffe’s civil defense effort, argued that the LS-Bunker program was “a bad policy psychologically because it tended to concentrate people in distant shelters, when it would have been more convenient to be sheltered near their homes and therefore available to defend them against incendiary attacks.” He favoured both improved cellar shelters and more enclosed trenches.

By 1945, life in the wartime public air-raid bunkers was cramped and uncomfortable, but it was infinitely safer than most other alternatives. This is the interior of the shelter in Krefeld shown in the accompanying photo. By this stage, the city had been captured by the Ninth US Army and so no longer had to fear bomber attacks. However, many civilians remained in the shelters since their homes had been destroyed, and others used the shelters to avoid artillery shelling by the Wehrmacht. (NARA)

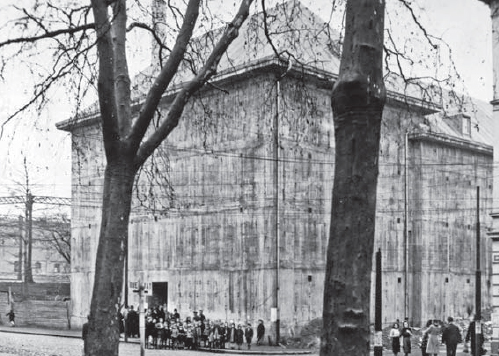

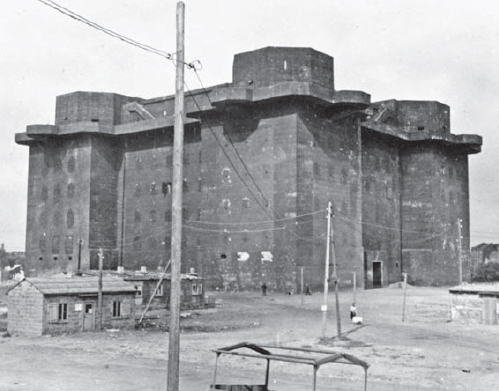

The earliest forms of LS-Bunker was the airraid tower (Luftschutz-Türm, or LS-Türm) which first began to appear in the mid-1930s. They were primarily intended for industrial sites, and the main attraction of this configuration was that it did not take up a great deal of acreage on a site. It was especially suitable for existing rail yards, dockyards, and factories where space was already at a premium. The conical cap of the tower was designed to deflect any bomb impacts, with the presumption that the bomb would skid off the steep roof and fall to the base of the tower which was much thicker and better prepared to absorb the bomb’s explosion. The most common of these was the LS-Türm der Bauart Winkel developed by the Leo Winkel firm in Duisburg from 1934. The Winkel towers were distinctive for their futuristic bullet shape; in Germany they were named Zuckerhut (“sugar loaf”) after a popular cone-shaped holiday confection. A prototype Winkel tower was tested at the Luftwaffe’s Rechlin proving ground and was subsequently adopted by the railway repair yards of the Reichsbahn. About 200 Winkel towers were built in several different models, constituting about a third of all of the towers built during the war. Other architectural firms favoured a neo-Romantic style hinting at medieval castle towers and using different internal layouts as shown in the accompanying plate on page 50. Often, a firm’s design won regional appeal, so for example, the LS-Türm der Bauart Zombeck developed by the Paul Zombeck firm in Dortmund in 1937 was adopted in Hamburg and 12 were built there, primarily near the main city railway stations. The typical LS-Türm could accommodate 500 people, but some of the larger designs could accommodate over a thousand and even more under emergency circumstances. Large-scale construction of the LS-Türm began in 1940 and about 500–600 were built. The towers were not as efficient in terms of material as more conventional “blockhouse” styles, and the construction of some designs became less common after national construction standards were released in the summer of 1941 that specified the ratio of concrete per occupant.

Although many shelter bunkers were built away from other structures, some were integrated into existing neighbourhoods such as this LS-Hochbunker at Kornerstrasse 107–111 in Cologne. It was designed by the architect Hans Schuhmacher and built in 1942–43 with accommodation for 1,550 people and 1,700 square metres (18,000 square feet) of floor space. It still exists today. (NARA)

Although the tower bunkers were the earliest and most distinctive air-raid bunkers, more conventional rectangular blockhouse designs predominated in urban areas during the war years. The rectangular bunkers were simpler and less expensive to build. The basic requirement in 1940 was for roof protection of at least 1.4m (4.5ft) of steel-reinforced concrete for the roof and at least 1.1m (3.5ft) for the side-walls, which was believed to be adequate against the 250kg (500lb) bombs common at the time. Since steel was at a premium, a variety of concrete reinforcement techniques were used. The traditional “cubical” method used steel reinforcing bars (rebar) uniformly distributed through the concrete casting. This method was standard in German bunker construction such as the Westwall, but this soon proved to be too expensive for the poorly funded shelter effort. In late 1940, a new technique was adopted in some bunkers, using spiral steel mats which reduced the amount of steel used for reinforcement, but which was somewhat complex to construct. Eventually, both approaches were replaced by the Brunswick style of reinforcement developed by the IfBL, which reduced the steel rebar near the surface, but concentrated it near the inner face of the slab. This reduced steel use from 300kg per cubic metre in the traditional cubical method to only 30kg (66lb). By 1941, Kristen’s IfBL recommended that the minimum standard for the bunkers be increased to 2.5m (8ft) to deal with the threat of 1,000kg (2,000lb) bombs. The Luftwaffe refused and set the minimum instead as 2m (6.5ft), though many cities adopted the 2.5m (8ft) standard based on Kristen’s recommendations.

This is another example of a LS-Hochbunker constructed within an existing neighbourhood of flats on Herthastrasse in Cologne. It was designed by the architect Ernst Nolte and built in 1942 with accommodation for 2,700 people and 2,715 square metres (29,000 square feet) of floor space. As can be seen, the bunker survived the bombing raids but the neighbouring apartment buildings have been gutted. This bunker still remains in Cologne, though has been heavily rebuilt. (NARA)

Although the bunkers offered excellent protection, they were by no means invulnerable. The air-raid bunkers suffered at least 120 direct hits during the course of the war, with known casualties of about 500. This two-story LS-Hochbunker on Rupprechtstrasse in Cologne was hit directly on the roof slab by a 900–1,800kg (2,000–4,000lb) bomb which penetrated the interior. This particular facility was designed by the architect Helmuth Wirminghaus with a capacity for 1,825 people and floor space of 1,070 square metres (11,500 square feet); it still exists today and has been used for office and factory space. (NARA)

This view shows an LS-Hochbunker built on Kornerstrasse in Hagen in 1941 intended to protect against 250kg (500lb) bombs. Although designed to accommodate 600 people, on the night of March 15, 1945, there were about 6,000 civilians in the structure when it was struck on the side by a heavy bomb in the 900–1,800kg range (2,000–4,000lb), killing about 290 people. (NARA)

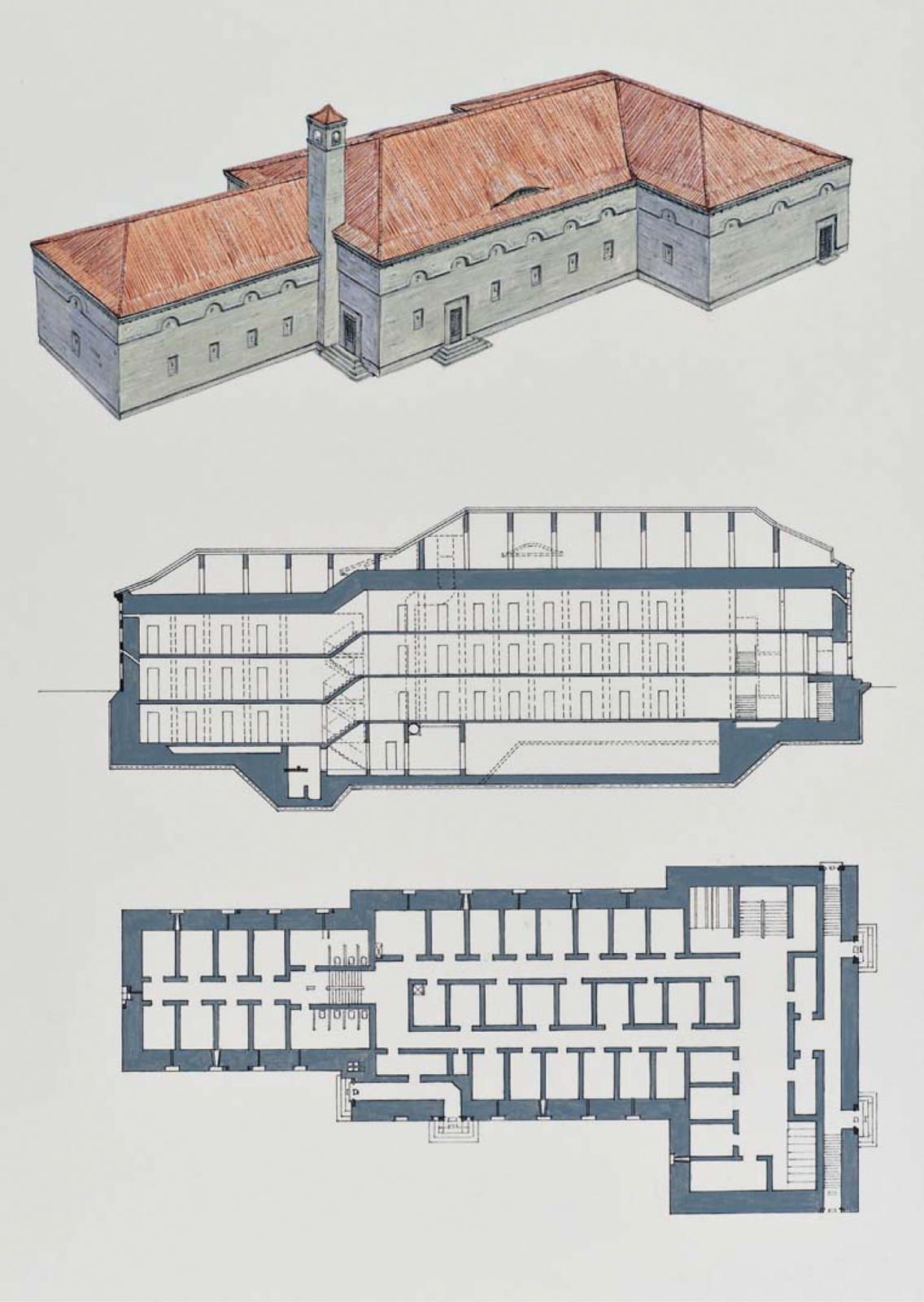

|

LS-HOCHBUNKER, TACITUSSTRASSE, COLOGNE |

This was a fairly typical example of the 1940–41 period urban air-raid shelters, designed to better blend into their local surroundings with false roofs and architectural adornment. This bunker resembles the several other Kirchenbunker (“church bunkers”) designed by Hans Schuhmacher in Cologne, with their distinctive steeples. This three-story bunker was designed to accommodate 1,490 people and had 1,560 square metres of floor space (16,800 square feet). In 1942–43, the building was used by the Nazi party’s regional administration (NSDAP-Gauleitung) and after the war, it was used by the Bundeswehr.

The effectiveness of the LS-Bunker concept is nowhere more evident than this aerial photo of a LS-Hochbunker in Bremen in 1945 with all the neighbouring homes completely burned out and gutted while the shelter remains intact and undamaged. (NARA)

In July 1941, the Luftwaffe released a set of pamphlets on air defense shelters that laid out basic design requirements. Three basic construction levels (Baustufe) of bunkers varied by the thickness of the roofs and walls: Baustufe A (3m/10ft); Baustufe B (2.5m/8ft) and Baustufe C (2m/6.5ft). The recommended designs were also tailored to the size of the building with the higher A level of protection being intended for large shelters of 1,500–3,000 people, B standards for 300–1,500, and C standards for small bunkers under 300 people. The 1941 instructions provided only a basic guideline for the design of the bunkers, and these were usually developed in more detail by local architectural firms. Some cities adopted their own common designs. Hanover, for example, adopted five standard designs designated as B, C, H.I, H.II, and H.III, with several intermediate variations; the H.II.4 bunker used the basic H.II floor-plan, but had four floors, for example.

The early bunkers offered a relatively high level of comfort to their inhabitants. They were provided with bunk beds, toilet, and wash facilities, an independent electrical supply for lighting and air filtration, and a heating system for the winter months. The early designs also went to some lengths to blend into the local neighbourhoods. This was done in part to satisfy urban planners, who abhorred the military’s ugly concrete bunker designs, but a secondary reason was for camouflage.

Although the 1940 Sofortprogramm did not favour the construction of large underground air-raid bunkers (LS-Tiefbunker), a number of these were built during the war. Due to their high cost, they were constructed mainly at political and military headquarters. The best known of the deep bunkers was the Führerbunker, constructed in the Chancellery building (Reichskanzlei) in Berlin. The original bunker was built under the garden of the Chancellery from 1936. When the new Chancellery was built, portions of the basement were earmarked for use as air-raid shelters. With the intensification of RAF bombing of Berlin in 1943, a deeper bunker was added, with the old bunker being renamed as the Vorbunker and the new bunker becoming the well-known Führerbunker where Hitler spent his final days. Aside from the Führerbunker, the most notorious of the deep bunkers was the LS-Tiefbunker built near the harbour in Danzig near the contemporary Plac Dominikanski. In 1945 during the siege of Festung Danzig, Red Army artillery knocked out the pumps used to drain the water out of the bunker, and rubble blocked the exits. As many as 4,500 people inside were drowned in what was probably the single worst air-raid shelter calamity of the war.

Tunnels were sometimes used for air-raid shelters and known as LS-Tiefstollen. In some cases they were expressly built for this function, but the majority of air-raid tunnels were existing railroad and mining tunnels adapted to this function and were not purpose-built. The mixture of bomb-proof shelters varied by region, but in the case of the heavily bombed north Rhine region, 76.5 percent were surface bunkers, 11.8 percent were underground bunkers and 11.7 percent were tunnel shelters.

Besides normal air-raid shelters, many cities installed specialized hospital bunkers (Krankenhausbunker). This particular example was one of the largest air-raid bunkers in southern Germany and was located in Frankfurt-am-Main. (NARA)

No doubt the most famous air-raid bunker in Berlin was the Führerbunker located under the Chancellery building. Here, British foreign secretary Ernest Bevin is given a tour of the area near the bunker entrance on August 2, 1945 during the “Big Three” conference. Hitler’s body was discovered by the Red Army a short distance from this entrance. (NARA)

Besides the civilian air-raid shelters, a variety of military air-raid shelters were constructed in parallel to the Sofortprogramm. The Kriegsmarine was the most active service in Germany in 1940–41 since the naval bases such as Wilhelmshaven and Bremen were so vulnerable to RAF bomber attack. The Kriegsmarine developed a number of standard air-raid bunkers (Truppenmannschafsbunkeren). The T-750, with a capacity for 750 troops, was one of the best-known types in the port cities.

The Luftwaffe did not fortify its airbases as heavily in Germany as it did in occupied Europe. Luftwaffe airbases in France, the Low Countries, and Scandinavia often had numerous small bunkers and pillboxes to serve as defenses against paratroop attack. This was a less serious threat in Germany itself, with correspondingly fewer strongpoints. Some airfields in Germany had reinforced command post bunkers (Gefechtsstand) but in general, the accent was on functional architecture rather than defensive works. When the threat of Allied fighter strafing increased in 1944, there was some effort to reinforce airfields in Germany, including an extensive effort to erect protective berms (Splitterboxen) around aircraft parking spaces; hardened aircraft shelters were not especially common. The Luftwaffe also had an extensive network of air defense command posts, often contained in large reinforced bunkers.

As mentioned earlier, Hitler was so enraged by the first RAF raids against Berlin that he ordered the construction of massive Flak towers in Berlin based on his own sketches. This program started in September 1940 and pre-dated the Sofortprogramm by a month. Although called Flak towers (Flaktürme) they were actually large air-raid shelters with Flak batteries on top. Hitler envisioned the towers as a means to remind the citizenry of Germany’s defiance of the British bombers, but also as a means to shelter precious museum artefacts and public documents. Any surplus space could be used for public air-raid shelters.

The sheer size of the proposed structures presented daunting design problems. Although the construction of the first Berlin towers was nominally under the control of Hitler’s personal architect, Albert Speer, the design work was actually undertaken by one of his subordinates, Prof. Friedrich Tamms. He completed preliminary designs and models in October 1940 with detailed drawings finished in March 1941 for Hitler’s approval. The Flak towers came in two varieties, the basic Gefechtstürm (G-Türm) mounting the Flak battery, and a supporting Leittürm (L-Türm) with an associated fire-control radar. The initial plan was for six pairs in Berlin, but spacing issues between the towers eventually limited the Berlin deployment to three pairs. For a time, there were plans to convert the Reichstag building into a Flak tower, but this scheme was eventually abandoned.

The principal armament of the Flak towers was intended to be four sets of twin 128mm anti-aircraft guns. However, the first towers were armed with four single 105mm Flak guns, replaced by the 128mm Flakzwilling 40 guns once they entered serial production in September 1942. The supplementary batteries were armed with 20mm and 37mm automatic cannon.

Once the “Zoo-Bunker” was completed, work began on two more Flak complexes in Berlin, the Gefechtstürm II in the Friedrichshain district, completed in October 1941 and the Gefechtstürm III in the Humboldthain district completed in April 1942. As in the case of the Tiergarten towers, Gefechtstürm II was used to house the treasures of the Kaiser Wilhelm museum. The fourth complex was built in Hamburg in the Heiligeistfeld area and was built on the same pattern as the Berlin towers.

During the course of construction of the first Flak complexes, Tamm’s team had developed a simplified and smaller tower for future construction, variously called Typ 2 or Bauart 2, which was used for the first time with Gefechtstürm VI located in the Wilhelmsburg district of Hamburg, completed in October 1942. This was the second and last complex built in Hamburg. In the meantime, Hitler had ordered the construction of Flak towers in Vienna, and the Gefechtstürm VIII in the Arenberg Park used the Typ 2 configuration when it was completed in October 1943.

The fourth of the Flak towers to be completed was the “Holy Ghost bunker,” Gefechtstürm IV in the Heiligengeistfeld area in Hamburg. It was built on the same Typ 1 pattern as the Berlin towers and was completed in October 1942. (NARA)

The “sparrow’s nests” on the sides of the Flak towers were used for light Flak positions such as this 37mm gun on Gefechtstürm IV in Hamburg. As can be seen, this particular position took a bomb hit during the war. (NARA)

The last two towers built in Vienna were the final Typ 3 configuration, which had a markedly different design than the previous types, with a circular base for the Gefechtstürm compared to the rectangular base in the previous two designs. The first of these, the Gefechtstürm V was completed in the courtyard of the Stiftskaserne in Vienna in September 1943, with the associated Leittürm V located in nearby Esterházy Park. The final tower was also in the Typ 3 configuration and Gefechtstürm VII was built in the Augarten district of Vienna in 1944.

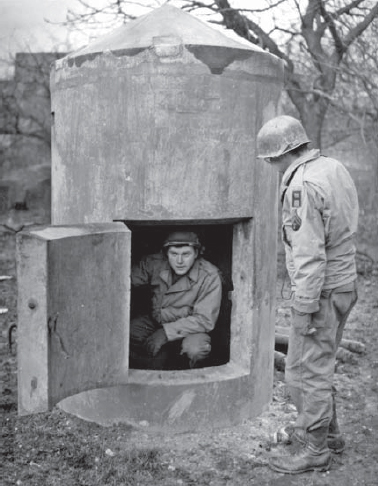

At the opposite end of the size spectrum from the massive Flak towers were the ubiquitous Brandwachenständ (BWS, or “fire warden stand”). They were also called Splitterschutzzellen (SSZ, or “splinter-proof compartment”) or Einmannbunker (“one-man bunker”). These were developed by private firms in the early 1930s for security guards at factories. The early designs were most often constructed from steel, and so provided ballistic protection. They began to attract government attention during the early war years due to their obvious utility for a variety of military and civil defense applications. The most common air defense application was as a shelter for fire wardens. German air defense practice assigned fire wardens the task of directing stray civilians to air-raid shelters during an air-raid. In addition, the fire departments needed observers around the city to provide information on fires or other problems. The BWS provided a means of security for the fire warden in the midst of an air-raid.

A view of the Hamburg Gefechtstürm IV in the Heiligengeistfeld district. After the war, it was turned into emergency apartments for war refugees, and in 1956 was converted into the Hochhaus II art centre. (NARA)

The second Flak complex in Hamburg was built in the Wilhelmsburg district but was built in the simplified Typ 2 configuration as seen here in the case of Gefechtstürm VI. This complex was demolished in 1947. (NARA)

The associated Leittürm VI in the Wilhelmsburg district of Hamburg was also completed in the simplified Typ 2 configuration. The Gefechtstürm VI can be seen in the background. (NARA)

Although the early BWS were often of steel construction, during the war years, they were increasingly made from concrete. The concrete offered better insulation than steel, and was more widely available after 1941 when steel was reserved for military needs. Thousands of these small shelters were built during the war by numerous small private firms. Although used mainly for fire wardens, they continued to be used for other security applications by industrial guards, railroad guards, concentration camps, and military police. They became ubiquitous through occupied Europe, and were often erected as guard posts near German bases and military facilities. When the Allied armies reached German soil in 1944–45, these small positions were often used as improvised tactical defense points. Besides the small cupola-style BWS, a large variety of other fire warden structures were built during the war. Reinforced concrete towers were also used in some areas to provide the fire wardens with greater visibility of the surrounding area.

The Sofortprogramm was delayed by the invasion of Russia in June 1941, which drained the country of military trucks and also led to the dispatch of most army and navy construction battalions to new assignments. Although the plan had been to complete Phase I by November 1941, this was delayed until the spring of 1942 in many locations. By the beginning of 1942, 1,215 bunkers had been completed and 515 more were under construction by year’s end. About 4.8 million cubic metres (6.2 million cubic yards) of concrete had been used. A further extension of the effort was hampered by the diversion of resources to other large fortification programs, starting with the construction of U-boat bunkers on the French coast from 1941. Once this was underway, Hitler ordered the first steps in the construction of a “new Westwall” to begin on the Atlantic Coast in December 1941, a program that was substantially enlarged in March 1942 under a new Führer directive as the Atlantikwall. This drew away most of the Organization Todt resources that had been engaged in the civil defense effort in Germany; the Atlantikwall program eventually consumed about five times more concrete than that used in Germany for civil defense.

The final Flak tower to be constructed in 1944 was the Gefechtstürm VII in the Augarten, the popular Baroque gardens of Vienna. Two Vienna Flak complexes used the final Typ 3 configuration with simple round contours. The architect realized that the tower would be impossible to remove after the war, and planned to finish it in the style of the medieval Hohenstaufen castles with tiles and French marble. In the event, this decorative phase of construction never took place. Both Vienna Flak towers still remain, and the Augarten example is festooned with modern communication antenna and used for storage. (Wojciech Luczak)

Berlin was complacent about the air-raid threat, because of the RAF’s patchy performance in the first few years of the war. In 1940–41, the RAF targeted military objectives such as the railway network and oil production facilities. British bombers could not defend themselves in daylight against German fighters and were forced to resort to night bombing. However, navigation aids were so poor that bombing accuracy was abysmally low, and precision targets were often missed. In February 1942 the RAF changed its mission to ‘de-housing’ the German industrial workforce by area attacks against German industrial cities. It took months before the RAF could mount raids of sufficient size to directly impact the German war industry.

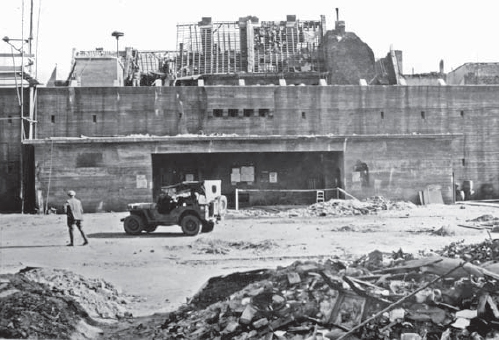

|

HOLY GHOST BUNKER, GEFECHTSSTAND IV, HAMBURG |

This shows Gefechtsstand IV, part of the Heiligengeistfeld Typ 1 Flaktürm complex in Hamburg, and popularly known as the Heiligengeistbunker (“Holy Ghost bunker”) by the local residents. This was a very substantial building, 70.5m (230ft) wide and 39m (130ft) high. The outer walls were 2.5m (8.2ft) thick while the roof was 3.5m (11.5ft). It followed the same Typ 1 pattern as the original Berlin Flak towers, with some minor architectural differences. This was the first tower to be built from the outset with the new 128mm Flak 40 Flakzwilling 40 (twin) heavy Flak guns. The secondary armament consisted of 20 20mm Flakvierling 38 automatic cannon. The battery was manned by 1./414 schwere Flak-Abteilung (Türm), 3. Flak-Division and during 1942–45 it was credited with downing 50 Allied bombers. Fire direction data came from the nearby Leitstand IV, but the battery had its own Kommandogerät 40 optical gun director located in the square parapet at the centre of the roof. The Flaktürme cost about RM 45 million for each complex. The Hamburg tower was designed to accommodate 18,000 civilians, although it sometimes held as many as 60,000 under very crowded conditions.

By the spring of 1942, the RAF was beginning to emerge as the scourge of German cities. This became painfully evident in May 1942 when the RAF launched its first ‘thousand-plane raid’ against Cologne. Cologne had been on the list of priority cities under the Sofortprogramm. By the spring of 1942, 25 bunkers capable of accommodating 7,250 had been completed with 29 more still under construction. Splinter-proof shelters for a further 75,000 civilians, or about a tenth of the city’s pre-war population of 760,000 people had been completed, mainly basement shelters and enclosed trenches. The Operation Millennium raid of May 30–31 delivered some 1,455 tons of bombs; casualties were about 460 dead and 5,025 wounded with more than 20,000 buildings damaged or destroyed. This was the last major raid until July 1943 when the RAF struck again. By 1944, the number of bunkers in Cologne had been increased to about 40 with a capacity of 12,000. Some of the capacity increase was accomplished by removing bunk beds and cramming in more people than the bunker’s nominal capacity. In addition, the number of splinter-proof shelters had been doubled so that there were places for about 200,000. In general, the civil defenses in Cologne were deemed to be adequate considering the limited resources available. Total spending on the air-raid bunkers in Cologne had been RM 24 million and on all air-raid shelters about RM 39 million – rather less than the construction of a Berlin Flak tower complex.

Through the end of 1942, there were major raids on 19 German cities totalling 12,600 tons of bombs. While this was a major escalation in the scale of bombing compared to 1940–41, it was only a mild foretaste of the apocalypse that would descend on Germany over the next 30 months of war. Phase II (Welle II) of the Sofortprogramm began in 1942, aimed at fortifying 51 cities. A lack of resources cut this objective to only 30 cities. By this time, about 6 million cubic metres (8 million cubic yards) of concrete had been used and about 3,000 bunkers constructed. Phase III began in May 1943 but was the least productive of the three stages of the program due to the lack of construction resources.

A post-war survey of the city of Bockum provides a picture of the typical mixture of shelter types in a German city during the war. The survey was broken down between large industrial and public shelters, and privately constructed shelters.

Although shelter building continued unabated through the war, the diversion of so many construction resources to the Atlantikwall and other programs severely undermined the completion of the Sofortprogramm beyond the first phase. A variety of steps were introduced to streamline the scheme, including the 1942 Notausbauprogramm (“Emergency Construction Program”), which forbad the use of architectural detailing on the bunkers. The Sofortprogramm was largely abandoned by 1944, to be replaced by the Mindestbauprogramm (“Minimal Construction Program”), which, as the name implied, was aimed at reducing construction programs to only the most essential efforts. As mentioned in more detail below, this represented a shift from civil air-raid protection to factory protection.

The British air campaign against the Ruhr industrial region in the summer of 1943 marked another major escalation in the air campaign. The arrival of the new Lancaster bomber substantially increased the payload of the British force, and better tactics and navigation improved accuracy. The RAF had also learned important lessons from British experiences against the German Blitz of 1940 regarding the destructive forces of air attack. While pre-war tactics stressed the use of high-explosive bombs, the 1940 Battle of Britain made clear the paramount importance of fire in city destruction. RAF tactics shifted to a synergistic use of high-explosive and incendiaries, the high-explosive bombs to crack open the roofs of German urban structures and expose the wooden interior which were then ignited with small incendiary bomblets.

| Air-raid shelters in Bockum | ||

| Type | Number | Accommodations |

| Large bunkers | 10 | 35,000 |

| Deep bunkers | 5 | 6,250 |

| Tunnels | 21 | 5,320 |

| Hospital tunnels | 4 | 4,100 |

| Old mountain tunnels | 4 | 5,100 |

| Mine tunnels | 370 | 24,000 |

| Newly constructed tunnels | 1,093 | 75,520 |

| Industrial/Public shelter subtotal | 1,507 | 155,290 |

| Basement shelters | 10,700 | 131,840 |

| Large enclosed trenches | 62 | 4,510 |

| Shelters in buildings and schools | 144 | 25,210 |

| Private enclosed trenches | 140 | 5,540 |

| Private shelter subtotal | 11,046 | 167,100 |

| Total | 12,553 | 322,390 |

These tactics reached their horrifying crescendo in Hamburg in July 1943 when the RAF launched Operation Gomorrah. Hamburg had a normal population of 1.6 million and the city had 131 air-raid bunkers with a capacity of 10 percent of the population. There were also 49 deep tunnel shelters, 345 enclosed trench shelters, and about 1,800 basement shelters. In total, the city had a shelter capacity for about 600,000 plus more with overcrowding. The attacks began on the night of July 24, and continued for eight days and seven nights. On the night of July 27, the dry summer weather and the local wind conditions accelerated the combustion, creating the first known instance of man-made cyclonic firestorms. This single night attack incinerated an area of about 21 square kilometres (8 square miles) and was responsible for the majority of the 42,000 deaths and 37,000 serious injuries caused by the operation. The basement shelters were especially vulnerable to the firestorms since they caused numerous building collapses and the occupants were asphyxiated by fumes or lack of oxygen. The small enclosed trench shelters were likewise vulnerable. The larger air-raid bunkers offered more reliable protection, if for no other reason than that they were often isolated from other buildings, which reduced the nearby stock of combustible materials. The vulnerability of the basement shelters and the better protection offered by the bunkers led to gross overcrowding. One Hamburg bunker designed for 18,000, was regularly occupied by more than 60,000 people.

This illustration compares the three generations of the Flakturme based on the architectural models prepared by the office of Prof. Friedrich Tamms. The gun towers (Gefechtstürm) are shown in the foreground, and the fire-control (Leitstand) in the background.

Pre-fabricated BWS (Brandwachenstände, or fire warden posts) were manufactured in the thousands. Some early BWS manufactured in the 1930s were constructed of steel like this example, currently preserved at the Overloon Museum in the Netherlands. Once steel became scarce in the civilian economy, concrete became the preferred material. (Author)

The lessons of Hamburg had an impact elsewhere. By 1944–45, bunkers and bomb-proof tunnels in the major German cities had a nominal capacity to house about 15 percent of their population, but in actual circumstances, overcrowding allowed them to increase their capacity five-fold and to accommodate as much as 75 percent of the population. The ventilation systems in the bunkers could not compensate for this volume of people and during warmer weather, the internal temperatures in the bunkers could reach 50ºC (120ºF), which caused serious medical problems for its temporary inhabitants. Nevertheless, they provided a more secure refuge than the improvised basement shelters.

Aside from overcrowding, the bunkers also proved to be increasingly vulnerable to the heavier bombs being dropped by the RAF. The bunkers built in 1940–41 with the 1.4m-thick (4.6ft) roofs were proof only against 250kg (500lb) bombs, at a time when the Lancaster bombers had begun to drop 2- and 4-ton bombs. A variety of improvised solutions were attempted such as “elastic roofs,” which consisted of a thick layer of straw on the existing roof and a further layer of concrete slabs above it. This was intended to detonate the bomb before it reached the main structure and dissipate some of its energy, but Luftwaffe officials were sceptical of the practice and banned it in late 1944 as ineffective.

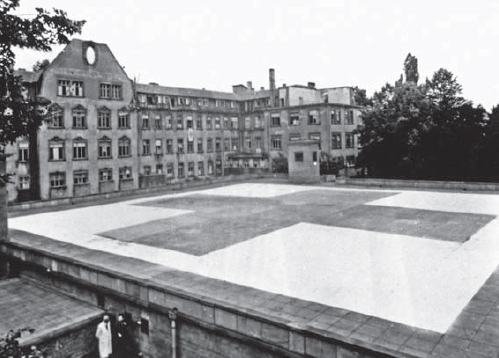

|

LEITTÜRM I, 1. FLAK-DIVISION, BERLIN |

The fire control towers of the Berlin Flak bunkers have not attracted as much attention as the larger gun towers. The first of these was Leittürm I, built in the Tiergarten at the Berlin Zoo. Codenamed Bär A (“Bear A”), its primary role was to provide fire direction for the gun tower. On the roof was a FuSE 65 Würzburg-Riese surveillance radar, as well as a smaller FuMG 39T fire control radar and a Kommandogerät 40 gun director. The “sparrow’s nests” in the control towers were supposed to be armed with the 50mm Maschinenflak 41 automatic cannon, but when this failed to enter serial production, the towers received the 20mm Flakvierling 38. The Zoo Bunker towers were painted dark green, but other Flak towers appear to have been painted in dark grey. This L-Türm served as the command post of the 1. Flak Division during the war. The Berlin tower guns were manned by schwere Flak-Abteilung 123 (T), Flak-Regiment 172, under Oberstleutnant Karl Hoffmann. During the final siege of Berlin in May 1945, the Zoo towers were the scene of considerable fighting with the Red Army, and nearly 30,000 civilians sheltered in both towers. The Leitturm I surrendered at 0500hrs on May 2, 1945 and it was demolished by British engineers on June 28, 1947. It is now the site of the bird preserve island in the Berlin Zoo.

This common type of concrete BWS was manufactured by the Dywidag Betonwerke in Cossebaude near Dresden. It weighed 3,240kg and cost RM 430 to RM 480. When the Allied armies entered Germany, they were often used as improvised pillboxes like this example captured after the fighting in Eschwiller in December 1944. (NARA)

Germany’s civil defense shelter program was surprisingly effective in reducing the number of civilian losses. Total German civilian casualties to the Allied bombing campaign were at least 305,000 killed and 780,000 wounded; records for the final months of the war are lacking and so the casualty figures were undoubtedly higher. While these figures are quite substantial, the German civil defense effort significantly limited these totals. Much of the credit for this must be given to local municipal governments since Hitler showed little enthusiasm for the air-raid shelter program beyond a few hallmark structures such as the great Flak towers. The success or failure of the civil defense infrastructure largely depended on local governments and most did a credible job in spite of the severe restrictions on construction resources. Hitler expected that the Luftwaffe would prove to be as effective in air defense as the RAF had been during the 1940 Battle of Britain. However, Britain had invested far more in heavy bomber technology, and neither German Flak nor fighter aircraft proved sufficient especially once the USAAF added its substantial power to the air battles. If Berlin had better anticipated the Allied air threat, greater efforts at civilian air defense could have taken place in 1942–43 by using the construction resources that were wasted on building the misguided Atlantikwall.