10

If You Don’t Know When to Say Yes, Always Say No

“If you don’t understand it, don’t do it.”

—WARREN BUFFETT1

“We know that we don’t know.”

—LARRY HITE2

I ONCE ASKED A FRIEND of mine, Andrew, one of my favorite questions: “How different would your net worth be today if you’d never made any investments at all, if instead you’d put all your money in the bank and let the interest pile up?”

“Oh, much worse off,” he replied. This puzzled me since I knew that in the previous three or four years he had lost money on every one of his forays into the stock market.

Andrew’s wealth came from two sources: the various businesses he had established, and real estate. So I asked him: “How different would your net worth be today if you’d only invested in your businesses or real estate?”

Without hesitation he replied: “Much better off.”

In real estate Andrew knew what he was doing. He had a simple rule: a return of 1% per month or he would walk.

Andrew made a common mistake. He assumed that because he was successful in real estate he could be successful in every investment market.

Although he had clearly defined his criteria for real estate investments, he did not realize that the key to investment success is to have criteria.

He deluded himself for four years until his staggering pile of losses forced him to admit that he didn’t understand the stock market at all. Only when, so to speak, he went back to investment kindergarten did he start making money in stocks.

When you enter an unfamiliar arena, regardless of your knowledge and skills you are in a state of unconscious incompetence. Mental habits that underlie success in one area can be so embedded in your subconscious that they lead to failure in another.

If you’re a good tennis player you have built up a repertoire of habitual ways of holding the tennis racquet, swinging it, serving, returning the ball, and so on.

The moment you move onto a squash, racquetball, or badminton court, nearly all these habits get in your way. You have to unlearn your good tennis habits and learn a whole new set of habits to succeed at any of these superficially similar, but in fact very different, games.

Andrew did not have a well-thought-out investment philosophy. He failed to clarify what he did and did not understand. He had not defined his circle of competence. So he didn’t know when to say yes and when to say no.

As Warren Buffett puts it, “What counts for most people in investing is not how much they know, but rather how realistically they define what they don’t know.”3

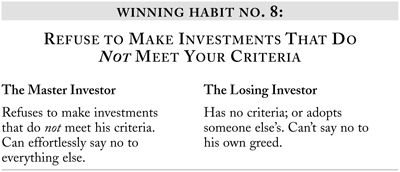

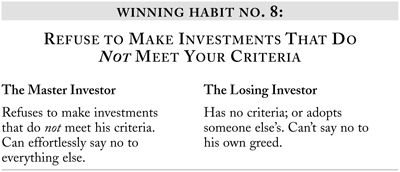

The Master Investor is very clear about what he does and doesn’t understand. So, when confronted with an investment he doesn’t understand, he’s simply not interested.

His attitude of indifference contrasts starkly with the behavior of the average investor, who lets his emotions color his judgment.

The Grass Is Always Greener

Investors who don’t have the mental anchor of a consistent investment philosophy often end up making investments against their better judgment. This always happens in manias like the dot-com boom.

In the early stages of such a boom, most investors are skeptics. They point out that companies such as Amazon.com, which projected losses as far as the eye can see, had no fundamental value whatsoever. Some of them even shorted such stocks, much to their later regret.

As the so-called New Economy party became more frenzied, the investment mantra became “profits don’t matter” and valuations became irrelevant. The prices of the dot-coms kept skyrocketing, while the Old Economy value stocks fell out of favor.

This confused the hell out of the skeptics. Sitting on the sidelines, all the evidence they could see—the rising prices, the profits that people around them were making—contradicted every investment rule they had applied successfully in the past.

Unable to make sense out of what was going on, they began to doubt and question their own investment beliefs, lost confidence in themselves, and, one by one, threw in the towel and joined the party. At the end of the mania, only the true “heretics”—those investors like Buffett with a firm philosophy all their own—stayed out of the fire.

As a result, sad to say, the skeptics are always among the biggest losers from a mania. Having held out till near the very end, they buy just before the bubble bursts … and lose their shirts.

This is an extreme example of the belief that the grass is always greener on the other side. Investors who see other people making money while they are not often succumb to self-doubt and pursue a mirage. Others, like Mary, discount their own knowledge and expertise as being worthless and seek their pot of gold on some other rainbow, totally unaware they’re already sitting on the right one.

The common denominator of this behavior is the failure to understand when to say yes and when to say no.

Contrast this with Warren Buffett, who at the height of a bull market in 1969 closed down the Buffett Partnership, writing to his investors:

I am not attuned to this market environment, and I don’t want to spoil a decent record by trying to play a game I don’t understand just so I can go out a hero.4

False Understanding

Even worse than succumbing to temptation and investing in things you don’t understand is to believe, falsely, that you do know what you’re doing. This is the state of the teenage driver who, even before he’s got his learner’s license, is convinced that driving is a piece of cake. Despite what he thinks, he’s in a state of unconscious incompetence.

In 1998 a friend of mine, Stewart, opened a brokerage account with $400,000 and proceeded to buy stocks such as Amazon.com, AOL, Yahoo!, eBay, and Cisco Systems. By the end of 1999, the value of his account had grown to $2 million, of which $800,000 was margin money.

Whenever I spoke to Stewart, as I did frequently, it was impossible to shake his belief in all the New Economy myths. “Warren Buffett has lost his touch,” he told me repeatedly. As his profits grew, his conviction that he knew exactly what he was doing became stronger and stronger.

Nevertheless, as the year 2000 dawned, he began to get nervous. He took a few profits, and shorted a few stocks as a “hedge.” Unfortunately, the market kept rising and he had to meet his first margin call.

By the end of the year, the value of the stocks in his portfolio had fallen back to his opening balance of $400,000—but he still had $200,000 of margin, and had to meet yet another margin call. Sad to say, the collapse hadn’t shaken his belief that the future of his dot-com stocks still glowed. And although everyone advised him not to, he paid his margin down with $200,000 from his savings. Today, with his portfolio down to about $200,000, it’s not advisable to ask Stewart about his investments.

His self-delusion that he was an expert on dot-com stocks led him to turn $600,000 of his savings into $200,000, so violating Investment Rule No. 1: “Never lose money.” (And its corollary: “Never meet a margin call.”)

That’s exactly why the Master Investor always says no to any investment he does not understand. By putting his capital at risk outside his circle of competence, he would be threatening the very foundation of his investment success: preservation of capital.

Defining Your Circle of Competence

The Master Investor is indifferent to investments he doesn’t understand because he knows his own limitations. And he knows his limitations because he has defined his circle of competence.

He has also proven to himself that he can make money easily when he stays within that circle. The grass may be greener somewhere outside his circle—but he’s not interested. His proven style of investing fits his personality. To do something else would be like wearing a suit that doesn’t fit. An Armani suit that’s too big or too small is worse than a cheap suit that’s your exact size.

Buffett and Soros built their circle of competence by answering these three questions:

• What am I interested in?

• What do I know now?

• What would I like to know about, and be willing to learn?

One other important consideration is whether it’s possible to make money in an area that intrigues you. For example, I’ve always been fascinated by airlines. But with one or two possible exceptions, the airline industry is an investment black hole requiring endless amounts of capital which usually ends up going to the pilots’ union.

Only by answering these three questions, as the Master Investor has done, can you find your investment niche and be crystal-clear about your own limitations. Only then will it be easy for you to walk away from investment “opportunities” that fail to meet your criteria—and stop losing money and start making it.