11

“Start with the A’s”

“If I’m interested in a company, I’ll buy 100 shares of all its competitors to get their annual reports.”

—WARREN BUFFETT1

“Discovery consists of seeing what everybody has seen and thinking what nobody has thought.”

—ALBERT SZENT-GYöRGYI VON NAGYRAPOLT2

EVERYBODY WANTS TO KNOW HOW Master Investors like Warren Buffett and George Soros find the investments that make them rich.

The simple answer is: on their own.

Buffett’s favorite source of investment ideas is available to anyone, usually free for the asking: company annual reports. In an interview with “Adam Smith” (author of Supermoney) Buffett advised novice investors “to do exactly what I did forty-odd years ago, which is to learn about every company in the United States that has publicly traded securities, and that bank of knowledge will do him or her terrific good over time.”

“But there are twenty-seven thousand public companies,” Smith responded.

“Well,” replied Buffett, “start with the A’s.”3

Buffett has been reading annual reports since 1950, when he first read Benjamin Graham’s book The Intelligent Investor. Today, in Buffett’s office, there are no quote machines, but in the file room are 188 drawers filled with annual reports. Buffett’s only “research assistant” is the person who files them. “I have spent my life,” he says, “looking at companies, starting with Abbott Labs and going through to Zenith.”4

As a result, Buffett has an incredible amount of information about all major American companies stored in his long-term memory. Which he continues to update … with the latest corporate reports.

When something he wants to know isn’t in the annual report he’ll go out and dig up the information. As he did in 1965, when …

Buffett says he spent the better part of a month counting tank cars in a Kansas City railroad yard. He was not, however, considering buying railroad stocks. He was interested in the old Studebaker Corp., because of STP, a highly successful gasoline additive. The company wouldn’t tell him how the product was doing. But he knew that the basic ingredient came from Union Carbide, and he knew how much it took to produce one can of STP. Hence the tank-car counting. When shipments rose, he bought Studebaker stock, which subsequently went from 18 to 30.6

It Pays to Advertise

Buffett began buying stocks, but today he prefers to buy entire companies. He quips that his strategy for finding them is “very scientific. We just sit around and wait for the phone to ring. Sometimes it’s a wrong number.”5

It’s true that the first contact is usually made by the prospective seller rather than by Buffett. But Buffett actively encourages people to give him that call.

From his comments to shareholders in Berkshire’s annual reports, referrals from his happy sellers, to even the occasional ad in the Wall Street Journal,Warren Buffett knows that it pays to advertise.

In this case, thanks to his fieldwork, Buffett could invest with conviction. He had learned something that nobody else outside the company knew. Others who might have had the same idea didn’t “go the distance” to confirm it.

The Master Investor’s secret is not so much seeing things that other people don’t see, but the way he interprets what he sees. And then being willing to “walk the extra mile” to back up his initial estimate.

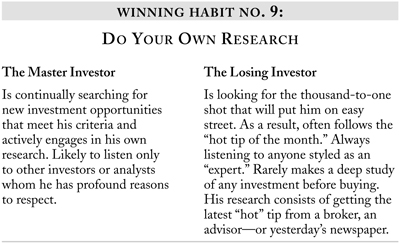

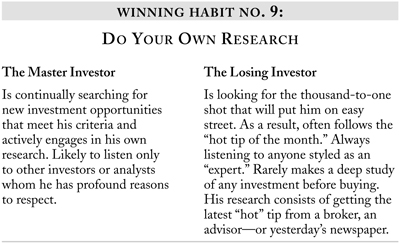

Buffett and Soros view the investment world through the filters of their investment criteria. They don’t care what other people think. Not only that, what other people think or say is of little or no value to them. Buffett even says, “You have to think for yourself. It always amazes me how high-IQ people mindlessly imitate. I never get good ideas talking to people.”7

It only makes sense to a Master Investor to depend on other people who share his investment philosophy and use the exact same filters just as successfully as he does—such as Buffett’s partner Charlie Munger and Soros’s successor at the Quantum Fund, Stanley Druckenmiller.

In the Kingdom of the Blind

Like Buffett, George Soros has always done his own research. He has always looked at the market differently from his investment peers, even before he founded the Quantum Fund.

When he first arrived in New York in 1956 he discovered he had a competitive advantage. In London, experts on European stocks were a dime a dozen, but in New York they were as scarce as hen’s teeth. That led to his first big breakthrough on Wall Street in 1959, when European stocks began to boom.

It started with the formation of the Coal and Steel Community, which eventually became the Common Market. There was a massive interest in European securities among United States banks and institutional investors who thought they were getting in on the ground floor of a United States of Europe.… I became one of the leaders of the European investment boom. It made me a one-eyed king among the blind. I had institutions like Dreyfus Fund and J. P. Morgan practically eating out of my hands because they needed the information. They were investing very large amounts of money; I was at the center of it. It was the first big breakthrough of my career.8

Some analysts with the same edge would simply sit in New York and enjoy being the resident “expert.” Not Soros. Like his ideas, his research was original and firsthand. Fluent in German and French, as well as English and Hungarian, he would delve into tax returns to unveil the hidden assets of European companies. And he visited the management—something almost unheard of in those days.

His independent research led to his first big coup in 1960. He discovered that the stock portfolios of the German banks were worth significantly more than their total market value. Turning to the German insurance industry, he found one group of insurance companies, Aachener-Muenchner, whose intricate cross holdings between the various group members meant some of those stocks could be had at an enormous discount to their real value.

Just before Christmas I went to J. P. Morgan, showed them the chart of these 50 interconnected companies, and told them my conclusion. I said that I was going to write it up during the Christmas holidays. They gave me an order to start buying immediately, before I completed the memo, because they thought that those stocks could double or triple on the basis of my recommendation.9

Today, Soros is known for his leveraged investments in futures and forward markets. But in 1969, when he and his then partner, Jimmy Rogers, established the Quantum Fund, futures contracts were only available for agricultural commodities such as wheat and coffee and metals such as silver and copper. The explosion of derivative contracts on currencies, bonds, and market indexes only began in the 1970s. Nevertheless, Soros applied the same principles before the advent of financial futures as he does now, seeking emerging industry trends that he could capitalize on by buying—or shorting—individual companies’ stocks.

How did Soros and Rogers find such stocks? They read. Intensely. Trade publications like Fertilizer Solutions and Textile Week. Popular magazines, looking for social or cultural trends that might affect the market. They pored through annual reports. And when they thought they had spotted a trend, they went out and visited company managements.

In 1978 or 1979, Soros recalled, Jimmy Rogers had the idea that the world was going to switch from analog to digital.

Jim and I went out to the AEA (American Electronics Association) conference in Monterey—it was called WEMA then—and we met with eight or ten managements a day for the entire week. We got our arms around this whole difficult field of technology. We selected the five most promising areas of growth and picked one or more stocks in each area. This was our finest hour as a team. We lived off the fruits of our labor for the next year or two. The Fund performed better than ever before.10

The growth of futures markets gave Soros a whole new arena to apply his philosophy of reflexivity. These highly liquid markets were ideal for the Quantum Fund. Soros could establish enormous positions far faster than he could in the stock market—and with little danger that his buying or selling would affect the price.

Soros switched his attention to monitoring political, economic, industry, currency, interest rate, and other trends, always on the lookout for linkages between disparate, unfolding events. His method hadn’t changed, merely his focus.

He also talked to people. He’d built up an enormous Rolodex of contacts in the markets around the world. He would sometimes call them to help him determine what Mr. Market was thinking.

Always highly self-critical, Soros was constantly refining his ideas. And if one of his staff really liked an idea, Soros would tell them to rethink their idea—and then think again. He’d also urge them to test it by talking to someone with the opposite point of view to see if their thinking measured up.

Both Soros and Buffett follow a rigorous, systematic approach to uncovering investments that meet their criteria. Personally in control of the process, they are willing to take every step necessary to ensure that they have found an investment with a high positive profit expectancy.

Compare this to the search process of the typical individual investor. He bases his investment decisions largely on second-hand information gained haphazardly from his broker, analyst write-ups, investment newsletters, financial TV programs, and newspapers and magazines. Only occasionally will he even bother to read a company’s annual report before buying its stock—let alone, as Buffett does, those of all its competitors.

Even fewer individual investors will go out and dig up firsthand information by talking to people involved with the company in one way or another, such as employees, customers, or competitors.

Even when he does follow a rigorous search strategy, he will often overlook one of the most crucial components of the Master Investor’s success: carefully monitoring, in a process just as rigorous as his search strategy, all the investments he has already made.

There’s No Such Thing As a One-Decision Stock

My own most vivid lesson in the importance of monitoring came from Harold, an investor I met when I was much younger than I am today. He was in his seventies when I first met him (so if he’s still alive now he’s well past the century mark). Harold began investing as a hobby, using the Value Line Investment Survey to find undervalued companies. He was having so much fun (and making so much money) that he quit his job when he was forty to invest fulltime.

He told me about his investment in a company I’ll call Paper Forms, Inc., which he had bought, in the late 1970s, at between $2 and $3 a share and finally sold at $21.

Paper Forms was in the business of making all manner of business forms. It had twenty factories and warehouses scattered all over the United States. What caught Harold’s eye was that all its premises had been leased for twenty years in the 1950s, with an option to buy at the end of the lease. The exercise prices of the options were set at levels that no doubt seemed high in the preinflation era of the late 1950s, but were ludicrously cheap in the era of double-digit inflation at the end of the 1970s.

Finding Baby Oak Trees

“You shouldn’t pay too much attention to what the market thinks. You should do your own research and decide what you think a stock is worth. You can often find some real acorns [i.e., that will grow into oak trees] there that everyone else, for all sorts of reasons, thinks are dangerous.

—Robert Maple-Brown11

The company was generating steady if unspectacular profits, so the only compelling reason to buy the stock was for the hidden value of the real estate options.

And buy it Harold did, accumulating a sizable stake at between $2 and $2.50 a share, becoming the biggest shareholder after the founder’s family.

If anything sounds like a stock you could buy and forget, surely this one does. But if Harold had taken that view, he would never have made a dime in Paper Forms. Because soon after he had started buying, the founder and controlling shareholder of the company died.

His shares ended up in the hands of a bank trust department. Control of the company now rested with the bank’s bean counters.

You’d think that even the dumbest member of the trust department wouldn’t pass over a windfall like the opportunity to buy real estate in the late 1970s at 1950s prices.

But to the bankers, options were dangerous derivatives. Exercising them would put Paper Forms in the risky business of real estate development. Better, in their view, that the company stick to its knitting. After all, what banker was ever criticized for taking the safe, conservative route?

The fact that the founder had died and the bank was now in control of the company was readily available, public information. But Harold knew from experience that with a change in management anything, even the ridiculous, could happen.

As Harold’s sole reason for buying stock in Paper Forms was those options, it was crucial that he know their fate. So by repeatedly phoning the company’s head office—and getting to know some of the middle managers in the process—he made sure he knew what the company was going to do. When he learned that in its wisdom the bank’s trust department had decided NOT to exercise the company’s options, he made an appointment to see the bank’s president.

When they met, he asked the bank’s president if it was true that his trust department had decided not to exercise Paper Form’s options. The bank president said he knew nothing about it, so Harold filled him in. Then he asked:

“How would you like to be the target of a class-action lawsuit on behalf of the minority shareholders for failing to maximize this company’s value?”

“Are you buying shares?” the president asked.

“You bet. And I’m going to keep buying.”

Thanks to Harold’s activism, the bank trust department changed its mind.

Harold continued to buy shares up to $3. Soon after, Paper Forms became the object of a takeover bid. The initial offer price was $18, but again Harold stuck to his guns and he wound up being bought out for $21 per share. If Harold had not actively monitored his investment, his entire profit of $18+ per share would never have come about.

Monitoring is a continual process. It’s a continuation of the search process, not to find an investment but so you know that all is well, or that it’s time to take a profit, liquidate the investment or, like Harold, take some other action to protect your capital.

Only the frequency of monitoring differs from one Master Investor to another. Buffett, for example, can safely review his investments on a monthly or even quarterly basis, while keeping his eye out for any news or development that might impact one of his companies in some way.

For Soros, the frequency of monitoring is far more intense, sometimes minute by minute rather than once every month or so.

And while, for Buffett, the distinction between searching and monitoring is clear-cut, in Soros’s investment style the two processes can merge together.

For example, Soros will first test his hypothesis by dipping his toe in the market. Monitoring that position helps him judge the quality of his hypothesis. His tests are also a component of his search strategy—searching for the right timing; the right moment to pull the trigger.

Monitoring his test helps him get a “feel for the market”; and the failure of a test may lead him to revise his hypothesis, so refining his search.

Despite the differences in their styles, both Buffett and Soros are personally on the lookout for new investments that meet their criteria at all times. And constantly measuring the investments they already own against their criteria to judge whether and when some further action is needed, whether to take a profit, a loss, or, like Harold, threatening a bank president with a class-action suit.