12

“When There’s Nothing to Do, Do Nothing”

“The trick is, when there’s nothing to do, do nothing.”

—WARREN BUFFETT1

“To be successful, you need leisure. You need time hanging heavily on your hands.”

—GEORGE SOROS2

“What was Soros’s secret…? Infinite patience, to start with.”

—ROBERT SLATER3

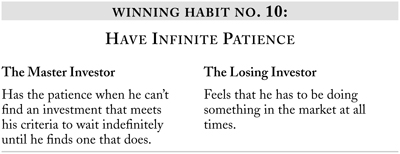

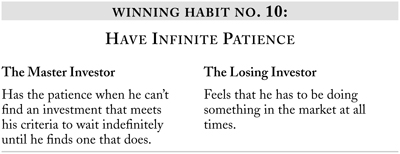

BOTH BUFFETT AND SOROS KNOW, and have accepted, that by sticking to their investment criteria there will be times, possibly extended periods, when they cannot find anything to invest in. Both have the patience to wait indefinitely. As Buffett quips, “Lethargy bordering on sloth remains the cornerstone of our investment style.”4

At Berkshire Hathaway’s 1998 annual meeting he told shareholders:

We haven’t found anything to speak of in equities in a good many months. As for how long we’ll wait, we’ll wait indefinitely. We’re not going to buy anything just to buy it. We will only buy something if we think we’re getting something attractive … We have no time frame. If the money piles up, then it piles up. And when we see something that makes sense, we’re willing to act very fast and very big. But we’re not going to act on anything if it doesn’t check out.

You don’t get paid for activity. You only get paid for being right.5

For Soros, periods of inactivity are far from frustrating. Indeed, he views them as essential. As he puts it, “To be successful, you need leisure. You need time hanging heavily on your hands.” Why? To have time to think. “I insist on formulating a thesis before I take a position,” he says. “But it takes time to discover a rationale for a perceived trend in the market.”6

And even when Soros has a solid investment hypothesis, he may have to wait quite a while before the time is right to pull the trigger. For example, when Britain joined the European “snake” in 1987, Soros knew that it would one day fall apart. It wasn’t until the reunification of Germany three years later that he could formulate a specific investment hypothesis, namely that the pound sterling would be thrown out. But two more years had to pass before it was time to go for the jugular. All in all, Soros had to wait five years before he could implement his investment idea. So, his profit of $2 billion was equivalent to $400 million for each year he waited. For the Master Investor, waiting pays off.

Buffett is perfectly happy to wait almost as long. “All I want is one good idea every year,” he says. “If you really push me, I will settle for one good idea every two years.”7

Getting Paid for Activity

The Master Investor’s incorporation of waiting into his investment system is a strategy that won’t fly on Wall Street. It’s a myth that the investment professional is paid for making you money. He’s actually paid to turn up every day and “do” something.

Analysts earn their keep by writing reports even when there’s no real reason for one to be written. Market commentators are paid to have an opinion, even on days when they have to invent one. Fund managers are paid to invest, not sit on piles of cash—even at those times when cash is king. Investment newsletter writers have to make a recommendation because a publishing deadline is looming, not necessarily because they’ve got a great stock to recommend.

The Master Investor is different.

As Soros once told his friend Byron Wien, Morgan Stanley’s US investment strategist:

“The trouble with you, Byron, is that you go to work every day [and think] you should do something. I don’t.… I only go to work on the days that make sense to go to work.… And I really do something on that day. But you go to work and you do something every day and you don’t realize when it’s a special day.”8

Master Investors like Buffett and Soros don’t suffer from these same constraints. There is no institutional imperative that forces them to act when their investment system dictates there’s nothing sensible to do. Unlike a typical fund manager, they don’t buy “defensive” stocks (i.e., stocks that will lose less money in a declining market than the market as a whole) when it makes more sense to just sit on a pile of cash.

Nor do they have to go to the office when there’s nothing to be done. Buffett learnt from Graham that “there would periodically be times when you couldn’t find good values, and it’s a good idea to go to the beach.”9

Or as Soros’s former partner Jimmy Rogers put it: “One of the best rules anybody can learn about investing is to do nothing, absolutely nothing, unless there is something to do.”10

Prospecting for Gold

The investor whose criteria are incomplete (or, more often, nonexistent) feels he must be in the market at all times. Waiting is alien to his mentality because, without criteria, he has no idea what to wait for. When he’s not regularly calling his broker saying, “Buy this, sell that,” he doesn’t feel he’s investing.

By contrast, the Master Investor is like a gold prospector. He knows exactly what he’s looking for; he has a general idea of where to find it; he’s got all the right tools; and he keeps searching until he discovers gold. And after he’s found one deposit and developed it, he gathers his tools and starts looking all over again.

In this sense, the Master Investor never waits. His time between strikes is filled with his daily activity of hunting for new opportunities. It’s a continual, never-ending process.

His only distraction from his search is the necessity to park his cash somewhere. Somewhere safe, so it’s immediately available the minute his investment system says it’s time for him to act.