14

Know When to Sell Before You Buy

“I know where I’m getting out before I get in.”

—BRUCE KOVNER1

“Sell when the company no longer meets your buying criteria.”

—T. ROWE PRICE2

NO MATTER HOW MUCH TIME, effort, energy, and money you put into making an investment, it will all come to naught if you don’t have a predetermined exit strategy.

That’s why the Master Investor never makes an investment without, first, knowing when he is going to sell.

Exit strategies vary from investor to investor depending on their method and system. But every successful investor has a selling strategy that’s compatible with his system.

Both Warren Buffett’s and George Soros’s exit strategies stem from their buying criteria.

Buffett continually measures the quality of the businesses he’s invested in with the same criteria that he used to invest in the first place. Though his favorite holding period is “forever,” he will sell a stock market investment when any of those criteria have been broken; for example, the business’s economic characteristics have changed, the management loses its focus, or the company has lost its “moat.”

In 2000, Berkshire’s filings with the SEC revealed that it had sold the bulk of its shares in Disney. Buffett was asked why he had sold this stock by a shareholder at the 2002 Berkshire annual meeting.

His policy is to never comment on his investments, so he answered the question obliquely by saying: “We had one view of the competitive characteristics of the company and that changed.”3

There’s no question that Disney had lost its focus. It was no longer the same company that made timeless family classics such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Disney’s CEO, Michael Eisner, had awarded himself options with a gusto that must have made Buffett squirm. They’d frittered money away in the dot-com boom, poured capital into Web sites such as search engine Goto.com, and bought other money losers such as InfoSeek. It’s easy to see why, in 2000, Disney no longer met Buffett’s criteria.

Buffett will also sell an investment when he needs the capital to fund an even better investment opportunity. But this isn’t something he has had to do since his early days, when he had more ideas than money. With the cash generated by Berkshire’s insurance float, his problem is now the opposite: He has more money than ideas.

His third rule for selling is when he realizes he’s made a mistake and should never have made the investment in the first place, the subject of chapter 16.

Like Buffett, George Soros has clear rules on when to liquidate an investment. And like Buffett, they are directly related to his criteria for making the investment.

He will take profits when his hypothesis has run its course, as in his coup against the pound sterling in 1992. He will take a loss when the market proves that his hypothesis is no longer valid.

And Soros will always beat a hasty retreat whenever his capital is jeopardized. The prime example of that is the way he dumped his long positions in S&P 500 futures during the crash of 1987—an extreme case of the market proving him wrong.

Regardless of his method, like Buffett and Soros every successful investor knows at the time he invests what will cause him to take either a profit or a loss. And he knows when to do so by continually measuring the progress of his investments against his criteria.

Exit Strategies

When they sell, Buffett, Soros and other successful investors all employ one or more of six possible exit strategies:

1. When Criteria Are Broken, as in the example of Buffett selling Disney.

2. When an Event Anticipated by their System Occurs. Some investments are made in anticipation of a particular event taking place. Soros’s hypothesis that the pound sterling would be devalued is one example; the time to exit was when the pound was kicked out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism.

When Buffett engages in takeover arbitrage, the time for him to exit is when the takeover is consummated—or when the deal falls apart.

In either case, the occurrence of a particular event determines when the investor takes his profit or loss.

3. When a System-Generated Target Is Met. Some investment systems generate a target price for an investment, which becomes the exit strategy. This is a characteristic of Benjamin Graham’s method, which was to buy stocks well below their intrinsic value and sell them when they rose to that value—or in two to three years if they did not.

4. When an Investor’s System Generates a Sell Signal. This is a method used primarily by technical traders whose sell signals may be generated by a particular chart pattern, volume or volatility indicator, or some other technical indicator.

5. When a Mechanical Rule Triggers Action, such as a stop loss set 10 percent below the entry point, or the use of a trailing stop (a stop that rises as the price goes up, but is not moved if the price goes down) to lock in profits. Mechanical rules are most often used by successful investors or traders who follow an actuarial approach, the rules being generated by the investor’s risk control and money management strategy.

One intriguing example of such a mechanical exit strategy was used by the grandfather of a friend of mine. His rule was to sell whenever a stock he owned went up or down by 10 percent. By following this rule, he survived the crash of 1929 with his capital intact.

6. When the Investor Realizes He Has Made a Mistake. Recognizing and correcting mistakes is essential to investment success, as we’ll see in chapter 17.

The investor with incomplete or nonexistent criteria is clearly unable to use the first exit strategy. And neither will he know when he’s made a mistake.

An investor without a system cannot have any system-generated targets or sell signals either.

His best bet is to follow a mechanical exit strategy. This will at least limit his losses. But it gives him no guarantee that he’ll ever make any profits because he has not done what the Master Investor has done: first identified a class of investments with a positive average profit expectancy and built a successful system around it.

“Cut Your Losses, Let Your Profits Run”

All these exit strategies have one thing in common: For the Master Investor, they take the emotion out of selling.

His focus isn’t on the profit or loss he might have made in this investment; it’s on following his system, of which his exit strategy is merely one part.

A successful exit strategy cannot be created in isolation. It can only be successful when it’s a direct consequence of the investor’s investment criteria and investment system.

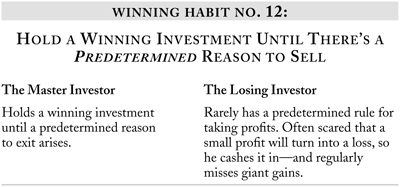

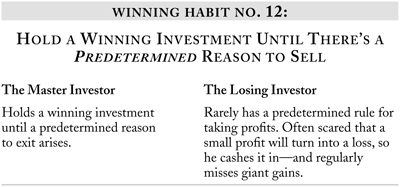

This is why the typical investor has such difficulty in realizing profits and taking losses. He has heard from every source that investment success depends on “cutting your losses and letting your profits run.” The Master Investor will agree with this—which is precisely why he has a system that allows him to successfully implement this rule.

Without such a system, the typical investor has nothing to tell him when a losing investment should be sold, or how long a winning investment should be held. How can he decide what to do?

Typically, both profits and losses cause him anxiety. When an investment shows a profit, he begins to fear that the profit might evaporate. To relieve that anxiety, he sells. After all, don’t the experts say “You can never go broke taking a profit”?

And of course he feels good when he banks a profit, even if it’s only 10 percent or 20 percent.

Faced with a loss, he might tell himself that it’s only a paper loss—as long as he doesn’t realize it. And he is ever hopeful that this is just a “temporary” correction and the price will soon turn around.

Getting Out of a Boom

“The lessons I’ve learnt are if you are participating in a boom, realize you are speculating not investing, always take your profits, cut your losses and when the boom ends if you have any speculative stocks left, sell them.… When the boom ends the bust is equally incredible in terms of the levels stocks can get to.”

—Anton Tagliaferro4

If the loss grows, he might tell himself that he’ll sell out when the price goes back to what he paid for it.

If the price continues to drop, eventually the hope that it will rise is replaced with fear that it will continue to fall. So he finally sells out, often near the ultimate bottom.

The overall result is that he ends up with a series of small profits which are more than offset by a string of much larger losses, the exact opposite of Soros’s recipe for success: capital preservation and home runs.

Without criteria, the question of whether to take a profit or a loss is dominated by anxiety. At each step along the way he finds himself reinventing all the reasons why the stock might be a good investment, convincing himself to hold on and so avoiding the issue.

Most people feel anxious when they are confused but must act regardless. An investor can procrastinate indefinitely about making an investment. But he cannot escape the decision to take a profit or a loss. He can only rid himself of this anxiety by clarifying his investment philosophy and criteria.