15

Never Second-Guess Your System

“I still go through periods of thinking I can outperform my own system, but such excursions are often self-correcting through the process of losing money.”

—ED SEYKOTA1

“For me, it’s important to be loyal to my system. When I’m not … I’ve made a mistake.”

—GIL BLAKE2

“Over the long run, I think my performance is best served by following my systems unquestioningly.”

—TOM BASSO3

JOEL IS A STOCK TRADER I met a few years ago through a mutual friend. He uses a technical system based on computer-generated buy and sell signals.

Even though he had been using his system successfully for over five years, he told me, he still had trouble selling stocks when the system told him to do so.

“I used to second-guess my sell signals all the time,” he said. “I could always think of a reason why the stock was going to keep going up. Then one day, a couple of years ago, I sat down and analyzed all the stocks I’d sold or should have sold. I found that second-guessing my system had cost me a hell of a lot of money.”

“So now,” I asked him, “you follow every sell signal religiously?”

“Yes, but I still have to literally force myself to. It’s like I close my eyes and call the broker.”

So why did Joel have a problem taking his system’s sell signals?

When given a buy signal, he would investigate the company and only take those buy signals when the company’s fundamentals stacked up.

When it came time to sell, nine times out of ten, the company’s fundamentals didn’t seem to have changed. Everything he knew about the company, everything he could see, conflicted with the computer-generated sell signal, so he was very reluctant to execute it. He was shifting his criteria in midstream, from the technical sell signals that he knew worked to fundamental ones that “felt” better but were irrelevant to the system.

Having realized how much it was costing him, now, when the computer says sell, he has disciplined himself to simply not look at any fundamental data.

Which is working—most of the time. But because his natural inclination is to also use fundamentals, he still occasionally second-guesses his system. Like most people, he can’t help but hear the siren call of temptation. Unlike most people, he can usually resist it.

He will always have this problem as long as he uses this system, because it doesn’t perfectly fit his personality. Joel’s Analyst tendencies (see box) get in his way.

Many successful investors are just like Joel: They have a system, they’ve tested it so they know it works, but they have trouble following it because some aspect of the system doesn’t fit their makeup.

A person who’s impatient and impetuous and who wants to see instant results would never feel comfortable with a Graham-style investment strategy that requires him to wait two or three years for a stock to get back to its intrinsic value.

Similarly, someone who likes to quietly study and think through all the implications before acting simply doesn’t have the temperament for, say, foreign exchange trading, which requires instant judgment, gut feel, continual action, and constant connection to the markets.

A person who is only comfortable buying something tangible, something where he can see and even feel the value, would never be able to follow a system that invests in technology or biotech start-ups. If the products are only ideas, not even at the developmental, let alone testing stage, only potential value exists. There is nothing concrete or tangible for him to latch on to.

It’s easy to see, in these three admittedly extreme examples, that the investor will fail miserably if he adopts a system that is totally alien to his personality—even though it works perfectly for somebody else.

As Joel’s example shows, following a system that almost, but not quite, fits your personality can be profitable. Indeed, Joel is doing better than 99% of all investors. But Joel will always be fighting, and occasionally giving in to, the temptation to second-guess his system.

The Analyst, the Trader, and the Actuary

I have identified three different investor archetypes: the Analyst, the Trader, and the Actuary. Each takes an entirely different approach to the market, depending on his investment personality.

The Analyst is personified by Warren Buffett. He carefully thinks through all the implications of an investment before putting a single dime on the table.

The Trader acts primarily from unconscious competence. This archetype, epitomized by George Soros, needs to have a “feel” for the market. He acts decisively, often on incomplete information, trusting his “gut feel,” supremely confident that he can always beat a hasty retreat.

The Actuary deals in numbers and probabilities. Like an insurance company, he is focused on the overall outcome, totally unconcerned with any single event. The actuarial investment strategy is, perhaps, best characterized by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of Fooled by Randomness. Originally a mathematician, he now manages a hedge fund and is willing to suffer hundreds of tiny losses while waiting for his next profitable trade, which he knows, actuarially, will repay his losses many times over.

Like all such characterizations, these three investor archetypes are mental constructs illustrating extreme tendencies. No individual is ever a perfect example of any single one. Indeed, the Master Investor has mastered the talents of all three.

Yet, like everyone else, he has a natural affinity with one of the three archetypes and will tend to operate primarily from that perspective.

In the words of commodity trader William Eckhardt, “If you find yourself overriding [your system] routinely, it’s a sure sign that there’s something that you want in the system that hasn’t been included.”4

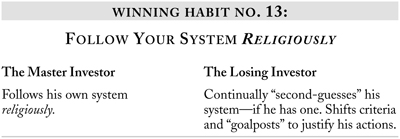

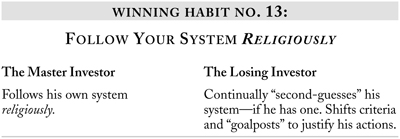

The difference between the merely successful investor and Master Investors like Buffett and Soros is that the Master Investor always follows his system religiously.

And unlike Joel, they never have to force themselves to do so. They can effortlessly follow their system 100 percent of the time because every aspect of their system fits them like a tailor-made glove.

Each has built his investment method himself, from the foundation of his investment philosophy to how he selects investments and his detailed rules for buying and selling. So he’s never even tempted to second-guess his system.

But that doesn’t mean he never makes a mistake.