16

Admit Your Mistakes

“Where I do think I excel is in recognizing my mistakes … that is the secret to my success.”

—GEORGE SOROS1

“An investor needs to do very few things as long as he or she avoids big mistakes.”

—WARREN BUFFETT2

“Quickly identify mistakes and take action.”

—CHARLIE MUNGER3

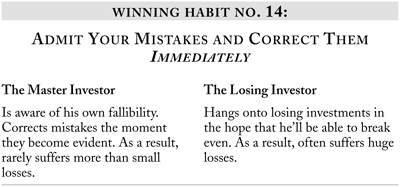

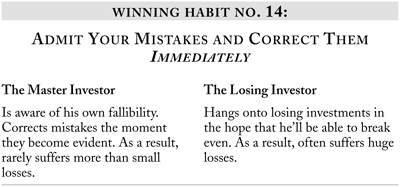

SUCCESSFUL PEOPLE FOCUS ON AVOIDING mistakes, and correcting them the moment they become evident. Sometimes, success can come from focusing solely on avoiding mistakes.

This is how Jonah Barrington became British and world squash champion in the 1960s and 1970s.

If you’re not familiar with the game of squash, it’s like racquetball. You have to chase a small rubber ball (the squash ball is harder than a racquetball and smaller, too—just the right size to fit into your eye socket, so it can be a dangerous sport) around an enclosed court.

The court is small, but the ball is fast. To get to the ball after your opponent has hit it, you have to sprint five to ten yards from a standing start, hit the ball back so it bounces off the front wall, and then get ready to sprint again … just a few seconds later. A champion squash player must be ready and able to sprint one short dash after another for four to five solid hours: A championship squash match can last longer than a hotly contested Wimbledon tennis final.

The sport is so physically demanding that people have died on court from heart attacks!

Barrington was determined to win, and win he did by consistently and continually aiming at one simple goal: to make no mistakes.

A mistake in squash, as in tennis, is to miss the ball, or to hit it out of bounds.

So Barrington aimed to always hit the ball, and to always hit it back to the front wall so that it stayed in play.

Like many simple goals, this one is far from easy to achieve. Barrington had to be incredibly fit and have amazing stamina.

He wore his opponents down. After three or four or five hours, his opponents were tiring. But Barrington was still there, still hitting the ball back, seemingly inexhaustible, while his opponents began to make mistakes, so losing the match.

In a sense, Barrington never won: His opponents always lost.

The Barrington Fund

If Barrington managed a mutual fund, it would probably be fully invested in Treasury bills at all times. Admittedly, he would never make significant profits, but by just avoiding mistakes he would never make a loss.

If you think that sitting on a pile of cash is a bad investment strategy, you should meet a few of the people I’ve coached over the years. As I mentioned earlier, one of my favorite questions is: “Imagine you’d never made any of your investments and just put your money in the bank. Would you be better off today?”

Even I was surprised when Geoff, one of my clients, figured out he’d have $5 million more in the bank today. Another client of mine, Jack, had thrown $7 million down the drain!

What these two gentlemen had in common was that they focused purely on profits. (Not that they ever made many.) Neither realized the importance of avoiding mistakes—not until, at my prompting, they added up their losses.

The wide-eyed focus on profits is not an attitude the Master Investor shares. Rather like Barrington, Berkshire vice chairman Charlie Munger “has always emphasized the study of mistakes rather than successes, both in business and other aspects of life,” as Buffett wrote in one of his letters to shareholders. “He does so in the spirit of the man who said: ‘All I want to know is where I’m going to die so I’ll never go there.’”4

Similarly, George Soros is constantly on the lookout for errors he may have made. “I’ve probably made as many mistakes as any investor,” he says, “but I have tended to discover them quicker and was usually able to correct them before they caused too much harm.”5

Since preservation of capital is the Master Investor’s first aim, his primary focus is, in fact, on avoiding mistakes and correcting any he makes; and only secondarily on seeking profits.

This doesn’t mean he spends most of his day focusing on what mistakes to avoid. By having carefully defined his circle of competence, he has already taken most possible mistakes out of the equation. As Buffett says:

Charlie and I have not learned how to solve difficult business problems. What we have learned is to avoid them.… Overall, we’ve done better by avoiding dragons than by slaying them.6

It should be no surprise to learn that Warren Buffett’s favorite book on his favorite pastime, other than reading annual reports, is Why You Lose at Bridge.

“Unforced Errors”

Most people think of investment mistakes and losses as being equivalent. The Master Investor’s definition of a mistake is more rigorous: not following his sytem. Even when an investment that did not fit his criteria ends up being profitable, he still views it as a mistake.

If the Master Investor follows his system religiously, how can he make a mistake of this kind?

Unwittingly.

For example, in 1961 Warren Buffett put $1 million, one-fifth of his partnership’s assets, into buying control of Dempster Mill Manufacturing. This company, in a town ninety miles from Omaha, made windmills and farm implements. In those days, Buffett was following Graham’s approach of buying “cigar butts,” and Dempster fitted perfectly into that category.

Experience

“What is the secret of your success?” a bank president was once asked.

“Two words: Right decisions.”

“And how do you make right decisions?”

“One word: Experience.”

“And how do you get Experience?”

“Two words.”

“And what are those words?”

“Wrong decisions.”

As the controlling shareholder, Buffett became chairman. Each month he “would entreat the managers to cut their overhead and trim the inventory, and they would give it lip service and wait for him to go back to Omaha.” Realizing he had made a mistake in taking control, “promptly, Buffett put the company up for sale.”7

But there were no takers. He hadn’t appreciated the difference between being a minority shareholder and having control. Had he owned 10 percent or 20 percent of the stock, he could have easily dumped it. But with 70 percent he was trying to sell control, something nobody wanted.

Turning companies around, Buffett discovered, wasn’t his “cup of tea.” To correct his mistake, he turned to his friend Charlie Munger who “knew a fellow, name of Harry Bottle, who might be the man for Dempster.”8 Bottle cut costs, slashed inventory, and squeezed cash out of the company—which Buffett reinvested in securities.

Buffett finally sold Dempster, now profitable and with $2 million in securities, in 1963 for $2.3 million. As Buffett later admitted, he can “correct such mistakes far more quickly”9 when he’s just a shareholder than when he owns the business.

“The Secret to My Success”

Buffett readily admits his mistakes, as a glance through his annual letter to shareholders makes abundantly clear. Every other year or so, he’ll devote an entire section to his “mistakes du jour.”

Likewise, the very foundation of Soros’s investment philosophy is his observation that “I am fallible.” While Buffett “credits Charlie Munger with helping him understand the value of studying one’s mistakes rather than concentrating only on success,”10 Soros needed no such urging.

His method for handling mistakes is built into his system. “I have a criterion that I can use to identify my mistakes,” he writes. “The behavior of the market.”11

When the market tells him he’s made a mistake, he immediately “beats a hasty retreat.” If he did otherwise, he would not be following his system.

With his emphasis on his own fallibility, he logically equates recognizing his mistakes with being “the secret to my success.”

Having recognized he’s blundered, the Master Investor has no emotional qualms about admitting he was wrong, taking responsibility for his mistake—and correcting it. To preserve his capital, his policy is to sell first, analyze later.