17

Learn from Your Mistakes

“The chief difference between a fool and a wise man is that the wise man learns from his mistakes, while the fool never does.”

—PHILIP A. FISHER1

“One learns the most from mistakes, not successes.”

—PAUL TUDOR JONES2

“To make a mistake is natural. To make the same mistake again is character.”

—ANON.

IF YOU WANTED TO TEACH someone how to ride a bike, would you give him a book to read? Take him to a lecture where he could hear a long exposition of the physics of bike riding, how to keep your balance, turning and starting and stopping, and so on? Or would you give him a few pointers, sit him on a bike, give him a gentle shove, and let him keep falling off until he figures it out for himself?

You know that to try learning how to ride a bike from a book or a lecture is totally ridiculous. With all the explanation in the world, you still have to learn the same way I and my kids did—by making lots and lots of mistakes, sometimes quite painful ones.

“Can you really explain to a fish what it’s like to walk on land?” Buffett asks. “One day on land is worth a thousand years of talking about it.”3

In a sense, we’re programmed to learn from our mistakes. But what we learn depends on our reaction. If a child puts his hand on a hot stove, he’ll learn not to do it again. But his automatic learning might be: Don’t put your hand on any stove. He must analyze his mistake before he can discover that it’s okay to put his hand on a cold stove.

Then he goes to school, and what does he learn about mistakes there? In too many schools he is punished for making mistakes. So he learns that making mistakes is wrong, that if you make mistakes you’re a failure.

Having graduated with this carefully ingrained attitude what’s his reaction when, as is inevitable in the real world, he makes a mistake? Denial and evasion. He’ll blame his investment advisor for recommending the stock or the market for going down. Or he’ll justify his action: “I followed the rules—it wasn’t my fault!” just like the kid who screams “You made me do it.” The last thing he’s going to do with that kind of education is to be dispassionate about his mistake and learn from it. So, just as inevitably, he’ll do it again.

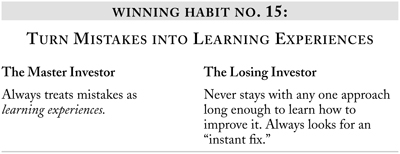

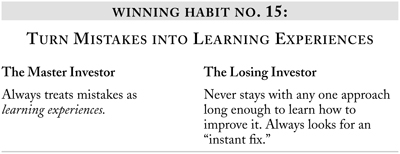

When the Master Investor makes a mistake, his reaction is very different. First, of course, he accepts his mistake and takes immediate action to neutralize its effect. He can do this because he takes complete responsibility for his actions—and their consequences.

Neither Buffett nor Soros has any emotional hang-up about admitting his mistakes. Indeed, both make it their policy to be frank and open about them. According to Buffett, “The CEO who misleads others in public may eventually mislead himself in private.”4 To Buffett, admitting your mistakes is essential if you are to be honest with yourself.

Soros is equally forthright. “To others,” he says, “being wrong is a source of shame; to me, recognizing my mistakes is a source of pride. Once we realize that imperfect understanding is the human condition, there is no shame in being wrong, only in failing to correct our mistakes.”5

Once the Master Investor has cleared the decks by getting rid of the offending investment, his mind is free to analyze what went wrong. And he always analyzes every mistake. First, he doesn’t want to repeat it, so he has to know what went wrong and why. Second, he knows that by making fewer errors he will strengthen his system and improve his performance. Third, he knows that reality is the best teacher, and mistakes are its most rewarding lessons.

And he’s curious to learn that lesson.

In 1962, Soros made a mistake that nearly wiped him out. It proved to be possibly his most powerful learning experience.

He had found an arbitrage opportunity in Studebaker stock. The company was issuing “A” shares which would become regular stock a year or so later. They were trading at a substantial discount to the ordinary shares. So Soros bought the “A” shares and shorted the regular Studebaker stock to pocket the spread. He also thought that Studebaker’s stock would first decline. When it did, he planned to cover his shorts, and then hold just the “A” shares for the expected recovery. If it didn’t, he figured he had locked in the spread.

The Master Investor’s Mistakes

A Master Investor’s errors usually fall into one or more of six categories:

1. He (unwittingly) didn’t follow his system.

2. An oversight: He overlooked something when he made the investment.

3. An emotional blind spot impaired his judgment.

4. He has changed in some way that he hasn’t yet recognized.

5. Something in the environment has changed that he hasn’t noticed.

6. Sins of omission … investments he should have made but didn’t.

But Studebaker went through the roof. And to make things worse, the spread widened as the “A” shares lagged behind.

Complicating Soros’s predicament, “I had borrowed money from my brother and I was in danger of being entirely wiped out.”6 It was money his brother—who was just starting his own business at the time—could ill afford to lose.

When the trade went against him, Soros didn’t beat a hasty retreat, but hung on, even putting up more margin money to keep his short position open. He was overextended; he hadn’t prepared an exit strategy to follow automatically if the trade went against him. He wasn’t ready for the contingency that he might be wrong.

After a prolonged period during which matters remained touch and go, Soros recouped his money, but the emotional impact of the ordeal was long lasting. “Psychologically it was very important.”7

This was his first major financial setback, and it caused him to rethink his entire approach to the markets. It’s certainly possible to trace many of the components of the investment system that turned Soros into a Master Investor to all the mistakes he made in this particular trade.

Buffett Takes Control

By taking control of Dempster in 1961, Buffett was clearly beginning to move away from the pure Graham system he had been following till then. The businessman inside him was seeking an outlet. But in buying a “cigar butt” like Dempster, he was doing it in a Graham-like fashion.

When he went for his next target, Berkshire Hathaway, he had clearly learned from his experience.

By 1963, the Buffett Partnership was the largest shareholder of the company. In May 1965 Buffett took control of the company—though he didn’t become chairman until later.

Immediately he told Ken Chace, whom he had previously identified as the man to run Berkshire his way and who was now president, his plans for the company. In a nutshell, he wanted Chace to do to Berkshire what Harry Bottle had done to Dempster: squeeze cash out of Berkshire’s dying textile business for Buffett to invest elsewhere. The first company that the new Berkshire bought—two years later—was National Indemnity Co., an insurance company.

In many respects, this is very similar to what Buffett does now, over three decades later. He buys a company with the management in place, and they run the business without his direct involvement—and send him all the spare cash to invest elsewhere. The major difference is that the companies he buys today are no longer cigar butts like Dempster and Berkshire Hathaway.

Buffett’s $2 Billion Mistake

Uniquely, Buffett also considers what could have been when he analyzes his mistakes.

In 1988 he wanted to buy 30 million (split-adjusted) shares in Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae), which would have cost around $350 million.

After we bought about 7 million shares, the price began to climb. In frustration, I stopped buying.… In an even sillier move, I surrendered to my distaste for holding small positions and sold the 7 million shares we owned.8

In October 1993 he told Forbes that “he left $2 billion on the table by selling Fannie Mae too early. He bought too little and sold too early. ‘It was easy to analyze. It was within my circle of competence. And for one reason or another, I quit. I wish I could give you a good answer.’”9

This was a mistake that, he wrote, “thankfully, I did not repeat when Coca-Cola stock rose similarly during our purchase program”10 which began later the same year.

“I Am My Most Severe Critic”

George Soros goes far beyond just analyzing his mistakes. As you might expect from someone whose philosophy and approach is based on his own fallibility, Soros views everything with a critical eye—including himself. “I am my most severe critic,”11 he says.

“Testing your views is essential in operating in the financial markets,”12 he tells his staff, urging them to be critical of their own ideas and always test them against somebody who holds an opposite view. He follows the same procedure himself, always looking for any flaw in his own thinking.

With this mind-set, Soros is constantly on the lookout for any discrepancy between his investment thesis and how events actually unfold. He says that when he spots such a discrepancy, “I start a critical examination.”13 He may end up dumping the investment, “but I certainly don’t stay still and I don’t ignore the discrepancy.”14

Soros’s willingness to continually question his own thinking and actions gives him a considerable edge over the investor who is complacent in his thinking and very slow to recognize when something is going wrong.

Like Soros, Buffett can also be hard on himself. Sometimes, too hard.

In 1996, Buffett once again became a shareholder of Disney when it merged with Cap Cities/ABC, of which Berkshire was a major shareholder. Buffett recalled how he had first become interested in Disney thirty years earlier. Then,

its market valuation was less than $90 million, even though the company had earned around $21 million pre-tax in 1965 and was sitting with more cash than debt. At Disneyland, the $17 million Pirates of the Caribbean ride would soon open. Imagine my excitement—a company selling at only five times rides!

Duly impressed, Buffett Partnership Ltd. bought a significant amount of Disney stock at a split-adjusted price of 31 cents per share. That decision may appear brilliant, given that the stock now sells for $66. But your Chairman was up to the task of nullifying it: In 1967 I sold out at 48 cents per share.15

With 20/20 hindsight, it’s easy to see that selling at 48 cents per share was a major blunder. But in criticizing himself for doing so, Buffett overlooks the fact that in 1967 he was still largely following Graham’s investment model. In that model the rule is to sell a stock once it reaches intrinsic value.

Nevertheless, he has clearly taken to heart Philip Fisher’s observation that studying “mistakes can be even more rewarding than reviewing past successes.”16

As the examples of both Buffett and Soros show, it’s better to be overly critical than forgiving of your own mistakes. As Buffett’s partner Charlie Munger puts it:

It is really useful to be reminded of your errors. I think we’re pretty good at that. We do kind of mentally rub our own noses in our own mistakes. And that is a very good mental habit.17