20

“Phony! Phony! Phony!”

“In evaluating people, you look for three qualities: integrity, intelligence, and energy. And if you don’t have the first, the other two will kill you.”

—WARREN BUFFETT1

“I am willing to use different people employing different approaches as long as I can rely on their integrity.”

—GEORGE SOROS2

ONE OF MY INVESTMENT COACHING clients was a woman from Singapore. In our initial conversation she told me that she chose her stocks based on the numbers she found in annual reports and elsewhere. “I do it, I’m good at it,” she said, “but I don’t really enjoy it.”

Later in this conversation she mentioned that she considered herself a good judge of character. So I said to her: “Well, why don’t you go along to the annual meetings of companies you’re looking at so you can meet, or at least observe, the company’s managers and directors. You can see if you’d feel comfortable giving your money to any of these guys to look after.”

This is an aspect of Warren Buffett’s investment strategy that’s usually underemphasized in all examinations of his investment approach: that he loves dealing with people as well as numbers, and he’s an incredibly good judge of character.

Walter Schloss is another Graham student who also worked at Graham-Newman Co. He has since averaged around 20 percent a year buying Graham-style investments. Comparing his style to Buffett’s, he says:

I really don’t like talking to management. Stocks really are easier to deal with. They don’t argue with you. They don’t have emotional problems. You don’t have to hold their hand. Now Warren is an unusual guy because he’s not only a good analyst, he’s a good salesman, and he’s a very good judge of people. That’s an unusual combination. If I were to [acquire] somebody with a business, I’m sure he would quit the very next day. I would misjudge his character or something—or I wouldn’t understand that he really didn’t like the business and really wanted to sell it and get out. Warren’s people knock themselves out after he buys the business, so that’s an unusual trait.3

As Ken Chace, whom Buffett promoted to run Berkshire, summed it up: “It’s hard to describe how much I enjoyed working for him.”4

“I Knew He Was a Phony”

How has Warren Buffett been able to acquire businesses whose owners end up “working harder for him than they did for themselves”?5

He is a superb judge of character. “I think I can tell pretty well what people’s motivation is when they walk in,” he says.6

In 1978, Warren Buffett was one of the few people in Omaha who closed his door to Larry King, a former Franklin Community Credit Union manager-treasurer who served a fifteen-year sentence [and is no relation to the CNN host of Larry King Live].

“I knew that King was a phony,” says Buffett, “and I think that he knew I knew. I’m probably the only person in Omaha he never asked for money.” How did Buffett know? “It was like he had a big sign on his head that said ‘PHONY, PHONY, PHONY.’”7

His unusual ability to gauge a person’s character accurately is a crucial aspect of Buffett’s investment and business success. It’s what allows him to buy companies with management in place, confident that the former owners will stay on to run the business indefinitely. He can decide whether a manager is “his kind of people” in moments—an ability Schloss admits he doesn’t have.

Whether he’s buying a business in whole or in part, Buffett always acts as if he were the owner hiring the management. So when he’s buying a stock he is effectively asking himself: “If I owned this company would I hire these guys to run it?” And of course, if the answer is no he won’t invest.

For Buffett, every investment is an act of delegation. He is fully aware that he is entrusting the future of his money to other people—and he’s only going to do that with people he respects, trusts, and admires.

He has two roles at Berkshire Hathaway. He says his primary role is the allocation of capital, a role he reserves to himself. But a second role, equally important, is to motivate people to work who simply have no need to.

One of his conditions when he purchases control of a company is that the existing owners stay on to manage it. Now independently wealthy, with lots of Berkshire Hathaway stock or cash in the bank, the previous owners continue to work as hard as ever, sometimes for decades—to make money for Buffett instead of themselves!

Part of his success is in choosing to only do business with people who simply love their work the way he does.

And part of it is the loyalty he inspires. Richard Santulli, who invented fractional ownership of private jets—and who sold the company he created, Executive Jets, Inc., to Berkshire Hathaway—put it succinctly when he said: “If Warren asked me to do anything, I would do it.”8

Such loyalty is rare in today’s corporate world. Yet Santulli’s sentiment would be echoed word for word by most chief executives of Berkshire’s many other subsidiaries. “Buffett’s respectful treatment of his managers has instilled in them an ambition to ‘make Warren proud,’ as one puts it.”9

Motivating previous owners to work just as hard after they’ve sold their company as they did before is a remarkable feat, one simply not achieved by any other company. By any measure, Buffett is an unsung genius at the art of delegation.

He’s so good at delegating that Berkshire has just fifteen people working at company headquarters—the smallest by far of any Fortune 500 company. This allows Buffett to focus on what he does best, allocating capital, which as we’ve seen is Buffett’s genius.

How Soros Learned to Delegate

In contrast to Buffett, delegation doesn’t come naturally to George Soros. “I’m a very bad judge of character,” he admits. “I’m a good judge of stocks, and I have a reasonably good perspective on history. But I am, really, quite awful in judging character, and so I’ve made many mistakes.”10

Nevertheless, he recognized early on that the fund could only continue to grow by expanding the staff—and it was over this issue that Soros and Jimmy Rogers split. Soros wanted to expand the team; Rogers did not.

So they agreed on a three-step plan, Soros said. “The first step was to try and build a team together. If we didn’t succeed, the second step was to build one without him; and if that didn’t work, the third step was to do it without me. And that is what happened.”11

In 1980 the partnership broke up. Soros was now in complete charge. But instead of building a team, as he had proposed, he ended up running the fund himself.

I was the captain of the ship and I was also the stoker who was putting the coal on the fire. When I was on the bridge, I rang the bell and said “Hard left,” and then I would run down into the engine room and actually execute the orders. And in-between I would stop and do some analysis as to what stocks to buy and so on.12

Not surprisingly, by 1981 Soros was breaking under the strain, and he had his first losing year. The fund lost 22.9 percent. Worse, a third of his investors pulled their money out, fearful that Soros had lost his grip.

So Soros stepped back, turning his fund into a “fund of funds. My plan was that I would give out portions to other fund managers, and I would become the supervisor rather than the active manager.”13

This turned out to be a mistake, partly because Soros was delegating the task he did best: investing. Soros describes the three years that followed as lackluster ones for the Quantum Fund. But by taking a backseat he was able to recover from a problem he (like all traders) faced, that an investor like Buffett doesn’t. It’s called “burnout.”

Trading is highly stressful. It requires total concentration for extended periods of time. Writing about his experience in 1981, Soros said, “I felt the fund was an organism, a parasite, sucking my blood and draining my energy.”14 He was working like a dog “and what was my reward? More money, more responsibility, more work—and more pain—because I relied on pain as a decision-making tool.”15

In 1984 Soros took back the helm. Though his experiment in delegation hadn’t been fully successful, Soros was rejuvenated and in 1985 the fund was up 122.2 percent.

That was also the year that Gary Gladstein came on board. Now, at last, Soros no longer had to worry about the administrative side of his business.

But Soros kept trying to find a successor to take over his role as chief investor. He finally succeeded when Stanley Druckenmiller joined him in 1988. When Druckenmiller was introduced to Soros’s son Robert, he was informed that he was “number nine, my father’s ninth successor.”16 As Soros wrote:

It took me five years and a lot of painful experiences to find the right management team. I am pleased that finally I found it, but I cannot claim to be as successful in picking a team as I have been in actually managing money.17

Druckenmiller ran the Quantum Fund for thirteen years. But for the first year it was far from clear how long he would stay. He had been hired to be captain of the ship, but Soros had great difficulty in letting go.

Then, in 1989, the Berlin Wall collapsed and Soros spent most of the next five months setting up his Open Society Foundations in Eastern Europe. “When I finally heard from him, he acknowledged I had done extremely well,” Druckenmiller recalled. “He completely let go and we never had a contentious argument since then.”18

Though delegation never came easily to Soros, eventually, after many trials and tribulations, he in fact delegated more of his responsibilities than Buffett has. When Druckenmiller took full charge, says Soros, “we developed a coach-and-player relationship, which has worked very well ever since.”19 Their relationship was somewhat akin to Buffett’s relationship with the managers of Berkshire’s operating subsidiaries, though far more intense.

And Soros was happy to let the reins go, to focus on his other activities. While Buffett quips that he plans to hold a seánce after his death for his successors. “I will keep working until five years after I die, and I’ve given the directors a Ouija board so they can keep in touch.”20

Teamwork

Knowing how to delegate is absolutely essential to investment success—even if you’re not Warren Buffett and you don’t have to figure out what to do with $31 billion in cash.21

We normally think of delegation as something to do when, like Soros, we want to find someone to take over from us. But all successful investing is a result of teamwork. As an investor you must delegate …

• when you open a brokerage account, you’re delegating the care of your money and the execution of your orders;

• when you invest in a mutual fund, commodity pool, limited partnership, or managed account you’re hiring a fund manager, so you’re delegating the investment function of decision making and delegating the care of your money;

• whenever you make an investment of any kind, you’re delegating significant (and at those times when the market moves dramatically, total) control of your money to Mr. Market (think about that: would you knowingly hire a manic-depressive money manager?); and

• whenever you buy shares of a company, you’re delegating the future of your money to the management.

Every act of delegation entails giving up control. Merely opening a bank account entails giving up control of your money to a group of people you have never met.

Successful delegation means you know what to expect. You know your brokerage account is segregated from the broker’s assets. You know when you give an order to your broker that it will be executed as you specify. You can hang up the phone and focus on other things—without having to keep tabs on him to see that it’s done the way you want.

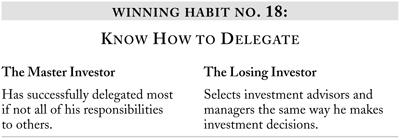

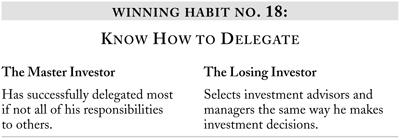

The Master Investor delegates authority, but he never delegates responsibility for delegating a task to someone else. “If you picked the right man, fine, but if you picked the wrong man, the responsibility is yours—not his.”22

And the Master Investor always takes responsibility for all the consequences of his actions. To be sure, he has more things to delegate than the average investor. But the rationale is the same: to free up his mind so that he can focus on the things he does best.