23

Master of His Craft

“I have enjoyed the process [of making money] far more than the proceeds, though I have learned to live with those, also.”

—WARREN BUFFETT1

IN 1956 HOMER DODGE, A physics professor in Vermont, drove halfway across the country to Omaha for one reason: to persuade Warren Buffett to invest his money. He had heard about Buffett from his friend Benjamin Graham.

Buffett had just started his first partnership with $105,100 from family and friends. He agreed to start a second one for Dodge, who became his first outside investor with $100,000.

Dodge’s son Norton has said, “My father saw immediately that Warren was brilliant at financial analysis. But it was more than that.”

The elder Dodge saw a uniquely talented craftsman who loved the process of investing and who had mastered all the tools.2

The master of any art is, first and foremost, the master of the tools of his trade, of his craft.

The artist has a vision of his painting, of his ultimate goal. But when he paints, his focus is on his craft, on the way he applies his brush to the canvas. He is absorbed by the process of painting. When he is totally involved in what he is doing, the master painter enters a mental state that psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls “flow.”3

Flow is a state where absorption is so complete that one’s entire mental focus is on the task being performed. The painter’s visual field will narrow so that all he sees is the painting, the brush—and be aware, in the back of his mind, of his image of the final result. His peripheral vision will be so contracted that he simply won’t notice anything going on around him. With his attention directed fully outward, he can even lose his sense of self, becoming instead (so to speak) the process of painting. His sense of time can disappear so completely that hours can go by, meals can be skipped, the sun can set and rise again, and he doesn’t even notice.

The master painter loves the process of painting not his tools. And whether he sells his paintings, while not irrelevant, is not the most important thing. Unlike those who paint those landscapes that clutter the walls of hotel rooms, the master painter doesn’t paint for money. He paints in order to paint.

The archetypal writer or artist starving in a garret may dream of seeing her book on the best-seller list—or of his paintings hanging in the Guggenheim Museum. But that vision isn’t going to motivate anyone to work for years in poverty and obscurity. If it’s the process of writing or painting—if that is where someone finds her satisfaction, then that’s where she’ll also find her motivation.

The common denominator between people who are masters of their own field is that they are motivated by the process of doing. The activity, not the outcome. The result—whether it’s money or winning medals for his roses—is an added bonus to entering a state of flow. As John Train put it in The Midas Touch:

The great investor, like the great chess player, is determined to become a master of that particular craft, sometimes without caring whether he only gets rich or immensely rich. It has been rightly said that the reward of the general is not a bigger tent but command. It is, in other words, succeeding in the process itself that fascinates the greatest investors.4

Investments for the Master Investor are like paint for the painter, the material he works with. An artist may love painting with oils, but it’s the “painting with,” not the oils, that he loves.

Keeping Your Eye on the Ball

Whether it be tennis, football, baseball, or hockey, players are always urged to “keep their eye on the ball.”

In practice this means: Where is your mental focus? Imagine you’re playing your favorite game. I’ll use tennis, and you can substitute whatever game you like.

Let’s say the score is one set each, and you’re down one game to five in the third set. If you lose the next game, you lose the match.

Imagine that you’re on the court and your focus is on winning the game. Every time you win a point you think of all the points you’re going to have to win in order to win the match. That makes you feel like you’re at the bottom of a very deep hole, with a long and difficult climb to get out. Every time your opponent wins a point, the hole gets a bit deeper. If you have ever watched a tennis match (or, indeed, any other sports game) you can tell, from the expression on their faces, which players have this mental focus. They look defeated. Even though the game isn’t over, even though other players have come from this far behind and won, it’s over for them.

Now imagine that you “keep your eye on the ball.” You put all your mental and physical energy into hitting the ball the best you can. Every ball. You know what the score is—but in this mental state, that doesn’t seem to matter any more. You’re no longer winning or losing; you’re just playing.

This will not guarantee a win. But I’m sure you can sense that the player who “keeps his eye on the ball” is going to give his opponent a much harder time.

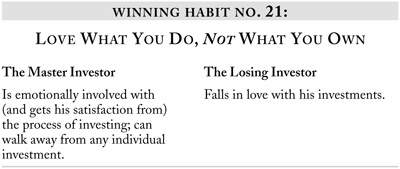

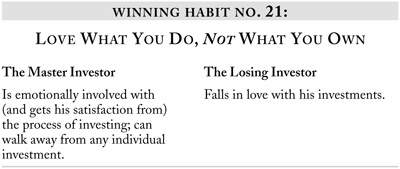

Where you have your mental focus determines your outcome. The average investor makes the mistake of focusing on the profits he hopes to make. In the extreme case, the investor “falls in love” with his investments. Like the gold bug, or the investor caught up in the tech (or other) bubble, he firmly believes, “These investments will make me rich.”

The Master Investor focuses on the process. George Soros, for example, is “fascinated by chaos. That’s really how I make my money: understanding the revolutionary process in financial markets.”5 In Soros’s view, calm and order in the financial world can never be more than a temporary hiatus. So there will be never-ending opportunities for the creation and testing of hypotheses to profit from chaos.

It’s worth looking at Soros’s most famous investment, shorting the pound sterling, in its proper context as but one of many Quantum Fund investments. In 1992 the fund was up 68.6 percent. If Soros and Druckenmiller had not “taken on” the Bank of England, their fund would still have been up 40 percent, well above their own long-term annual average.

Warren Buffett on Buying a Business

“The first question I always ask myself about [a business’s owner] is:

“Do they love the money [the effect] or do they love the business [the process]?… because the day after I buy a company, if they love the money they’re gone.”8

Nineteen ninety-two might have been Soros’s most famous year, but it wasn’t even his best. In both 1980 and 1985 the value of the Quantum Fund more than doubled. It was Soros’s mastery of his craft that made his sterling profit possible.

For many successful investors, the most rewarding and exciting part of the process is the search, not the investment he eventually finds. “[Investing] is like a giant treasure hunt,”6 says stock trader David Ryan. “I love the hunt,”7 says another.

This makes logical sense. The process of investing includes searching, measuring, buying, monitoring, selling—and reviewing mistakes. Buying and selling, the steps most people focus on, both take but a moment. Searching and monitoring are the most time intensive—and are never-ending processes. Only a person whose source of satisfaction is these activities will devote the time and energy necessary to master them and reach Master Investor status.

When Warren Buffett describes his typical day, it’s clear that he, too—when he’s not talking to his managers (monitoring)—focuses primarily on searching:

Well, first of all, I tap-dance into work. And then I sit down and I read. Then I talk on the phone for seven or eight hours. And then I take home more to read. Then I talk on the phone in the evening. We read a lot. We have a general sense of what we’re after. We’re looking for seven-footers. That’s about all there is to it.9

Does the Master Investor get pleasure from the profits he makes? Of course. But his real pleasure comes from his involvement in the investment process. His priority isn’t the investment he makes but the criteria he uses to make it. Any investment that does not meet his criteria is simply unappealing. Or, if he owns it, a mistake—which automatically changes his emotional reaction to it regardless of what he thought of it before.

And once the Master Investor has found an investment that meets his criteria, he’s off on the trail looking for another one.