27

Carl Icahn and John Templeton

WARREN BUFFETT AND GEORGE SOROS aren’t the only well-known investors on the annual Forbes magazine list of the world’s richest people. Nor are they the only investors on the list who started with nothing.

But until 2003, they were the two richest.

In the Forbes 2004 list of the world’s billionaires, Carl Icahn, with a net worth of $7.6 billion, topped George Soros (at $7.0 billion) for the first time, so becoming the world’s second richest investor.

So the obvious question is: Does he also practice the 23 Winning Investment Habits?

Carl Icahn: From Options to Takeovers

“If you want a friend on Wall Street, get a dog.”

—CARL ICAHN1

In late 1977, Carl Icahn began accumulating shares in an Ohio-based manufacturer of stoves, Tappan Company. He kept buying until he owned 20 percent of the company.

What did this New York–born options trader know about stoves—or manufacturing for that matter?

Not much. But he could read a balance sheet. And it was clear—to him—that the breakup value of the company of $20 a share exceeded its market price of $7.50 with a wide margin of safety.

Not everyone agreed that Tappan was a bargain. Litton Industries, for example, had considered taking over the company, but concluded it was in terrible shape, so they backed off.

And Icahn’s uncle, who years earlier had lent him $400,000 to buy a seat on the New York Stock Exchange, thought he was crazy. But he changed his mind when his nephew walked away with a profit of $2.7 million on his Tappan stock just one year later.

Tappan had another characteristic that appealed to Icahn: no controlling shareholder. Icahn set about changing that by building his position to 20 percent of the company.

His ultimate aim: to control the financial destiny of the company long enough to make a quick profit by finding another company to take it over at a much higher price. Or to persuade the management to have the company buy his shares back (“greenmail”)—he didn’t care, as long as he made money.

Shaking Up the Options Business

Icahn went to Wall Street in 1961 as a trainee broker with Dreyfus & Co. making $100 a week. It was boom time. It was easy to sell stocks. And Icahn was a good salesman.

Using a $4,000 grubstake he’d accumulated playing poker while training for the Army Reserve, Icahn was also buying for his own account. Like his clients, almost everything he bought for himself went up.

But when the bubble burst in 1962, Icahn lost everything he had made on the way up—over $50,000. He even had to sell his car, a white convertible, so he could eat.

To say this was a formative experience would be an understatement. But Icahn didn’t react as many might have done—by looking for some safer, securer field, like fulfilling his mother’s dream by becoming a doctor.

Quite the reverse. He realized that if you could lose so much money so quickly, you could make it just as a fast—if you followed a sound strategy instead of, as he had been doing along with his clients, mimicking the herd.

Icahn quickly bounced back, reinventing himself as an options broker. In the 1960s, there was no such thing as exchange-traded options. Buyers and sellers came together by haggling on the telephone.

It was a tiny investment niche, but rife with exploitable pricing inefficiencies. Which Icahn was quick to capitalize on.

Targeting Market Inefficiencies

He gained a loyal clientele by working the market to get his clients better prices than they could get anywhere else. Other brokers hated him for slashing their fat buy/sell spreads. At one point they even ganged up on him, boycotting him to try to squeeze him out of the business. But the minicartel cracked very quickly: Icahn had too much business to be ignored.

Eventually, in 1967, Icahn went into business for himself with his own seat on the New York Stock Exchange. He published a weekly options bulletin, which became the only publicly available source of options price information.

He expanded into arbitrage. And noticing a similar pricing inefficiency in closed-end mutual funds, which were almost all trading at significant discounts to the value of the assets they owned, he started buying them up.

Like both Buffett and Soros, Icahn clearly believes the efficient-market theory is a load of hooey. His entire Wall Street career has been built on finding and exploiting these kinds of market inefficiencies.

Icahn’s strategy in buying into closed-end funds was to “shake the tree” to force the management to liquidate the fund at a profit to the shareholders—most important, of course, Icahn himself.

The Lone Ranger and Tonto

Instrumental in Icahn’s success was his associate Alfred Kingsley, who joined him in 1968. Icahn delegated the number crunching to Kingsley, who would plow through the data to identify potential investment targets for Icahn to choose from.

One day over lunch, Icahn and Kingsley (who became known on Wall Street as the “Lone Ranger and Tonto”) realized they could apply the exact same strategy they’d used to make money in closed-end funds to other listed companies trading significantly below their book value.

And their timing was perfect. After the big bear market of 1973–74, triggered by the first oil shock, stocks rebounded slightly in 1975 but then more or less trended sideways until the biggest bull market in history began in 1982. There were bargains aplenty.

Another factor that appealed to Icahn’s distaste for losing money was that in the 1970s inflation was soaring; values for tangible assets like gold and real estate had skyrocketed, but these changes had yet to be reflected in corporate balance sheets. In this environment, plenty of stocks were trading below their book values, but thanks to inflation their discount to liquidation value was even higher. This offered Icahn an enormous margin of safety.

Tappan was just the first of many undervalued investments Icahn and Kingsley went after.

Beating the Bushes for a Buyer

But their strategy was always the same. As Icahn himself described it in the offer document for one of his early investment partnerships, their aim was to take

large positions in “undervalued” stocks and then attempting to control the destinies of the companies in question by (a) trying to convince management to liquidate or sell the company to a “white knight”; (b) waging a proxy contest; or (c) making a tender offer and/or (d) selling back our position to the company.2

Clearly, Icahn has a well-defined exit strategy that is inherent in his investment system. He doesn’t buy anything without having first carefully considered his exit plan. And unlike most investors, Icahn is actively involved in creating his own exit path by “beating the bushes” for the highest bidder.

Kingsley combed through listed companies to find those trading significantly below book or liquidation value, where no one, including the incumbent management, had a significant stake in the company.

After they’d identified a target, Icahn began quietly accumulating stock, buying as much as he possibly could.

When the management noticed, Icahn began playing what was to him like a high-stakes game of poker.

Playing Poker on Wall Street

First was his poker face. He introduced himself and his associate Alfred Kingsley to Tappan’s management as friendly investors “who might increase their investment further.” And to this end asked a series of näive questions about the company and its products.

Needless to say, Icahn already knew the answers. But he achieved his aim of lulling the Tappan management into a false sense of security, leaving them thinking he and Kingsley were “pleased that we took the time to talk to them about the company.”3

The great investors rarely talk to anyone about what they are doing in the markets. Icahn was different. In the second step of his strategy, to keep the management off guard, he’d talk and talk and talk. But the net effect was to sow so much confusion that no one had a hope of figuring out what he was really up to.

As he increased his stake in Tappan, the management became more determined to find out what he was really after. Icahn would mumble, ramble, and throw around a bewildering number of possibilities. Including, of course, the prospect of a takeover bid, pointing out that the undervalued price of Tappan’s shares was one factor that had attracted him to making the investment.

Or was he just a long-term investor? The management couldn’t be sure. They’d have done better if they hadn’t listened to Icahn at all.

This process gave Icahn time to continue building his position without unduly forcing up the price of the stock.

His third step was to seek a seat on the board. It was usually around this point that the management realized that whatever Icahn’s real intent, their security might be endangered. Feeling threatened, they took defensive action.

The Prize-Winning Philosopher

Icahn went to Princeton University where—like Soros—he studied philosophy. His thesis, “An Explication of the Empiricist Criterion of Meaning,” won first prize. And as it had for Soros, philosophy proved to be a key factor in Icahn’s later investment success.

“Empiricism says knowledge is based on observation and experience, not feelings,” Icahn said. “In a funny way, studying twentieth-century philosophy trains your mind for takeovers.… There’s strategy behind everything. Everything fits. Thinking this way taught me to compete in many things, not only takeovers but chess and arbitrage.”4

Going for the Jugular

The Tappan management proposed an issue of preferred stock. Seeing immediately that this would weaken his position by watering down his equity—and possibly send Tappan’s stock down—Icahn initiated the fourth element in his strategy: a proxy battle to win the support of the legions of small shareholders to his agenda. This was a tactic no one on Wall Street had ever used before to deliberately put a company “in play.”

Just the threat of Icahn going to the shareholders seeking to reverse a management decision caused the Tappan management to back off.

Sensing weakness, Icahn pounced and launched his proxy campaign anyway, aiming for a seat on the board. He told other shareholders his aim was to see “our company” sold for a price reflecting its true value of $20.18 per share, not the paltry $7.50 the stock had been languishing at on the stock market.

Icahn painted a devastating picture of the current management, pointing out that the company had lost $3.3 million over the past five years, while Tappan’s chairman and president had been paid over $1.2 million in salaries and bonuses.

Icahn won his seat, but entrenched board members held their noses and tried to ignore him. Meanwhile, Icahn set about finding an acquirer for the company. He went to leveraged buyout firms, private equity groups, and major companies in the United States, Europe, and Japan. But none were interested.

Tappan Caves In

At the same time he was pushing management to sell off parts of the company—or all of it—to return money to the shareholders. Eventually management, despairing of seeing Icahn liquidate “their” company, found a buyer in the Swedish home appliance maker Electrolux, which ended up buying Tappan for $18 per share in late 1978.

Icahn ended up with a profit of $2.7 million on his 321,500 shares. Ironically, chairman Dick Tappan became an Icahn convert—and a happy investor alongside Icahn in his many future takeover attempts.

Icahn had found the investment niche that would make him one of the world’s greatest—and richest—investors.

His raid on Tappan had worked like a dream. But Icahn didn’t even take time out for a glass of champagne, let alone a vacation. He and Kingsley were already hard at work on their next deal. A pattern they continued to follow over the next ten years, during which they used the same strategy to go after fifteen more companies like Tappan.

At any one time they were entirely focused on just one or two investments. Like Buffett and Soros, Icahn always buys as much as he can of the company that is in his sights, sometimes stretching his resources to the limit. He completely ignores the traditional advice about diversification—and reaps enormous rewards as a result.

He and Kingsley targeted companies like Gulf & Western, Goodrich, Marshall Field, and Phillips Petroleum. All traded at large discounts to their book value. None had substantial shareholders, so the management—Icahn’s only competitor for control—was vulnerable to Icahn’s strategy of a proxy battle. All had readily marketable assets, or were appealing takeover candidates.

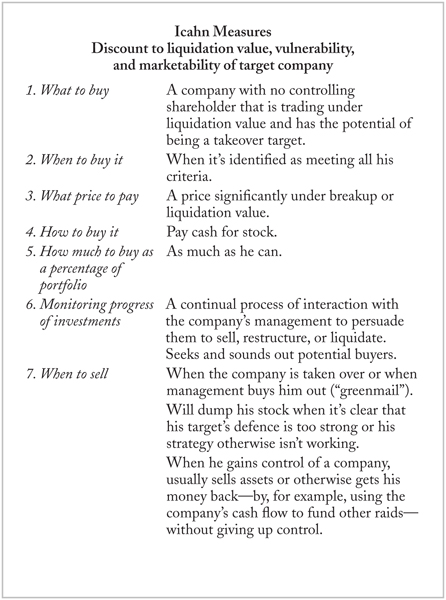

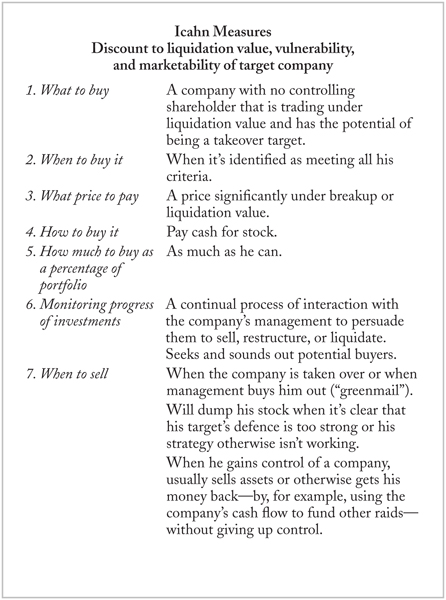

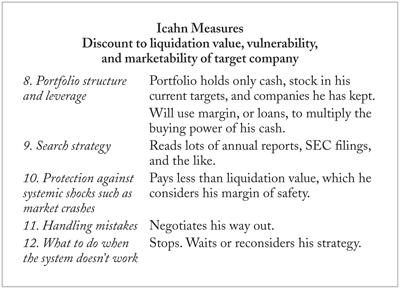

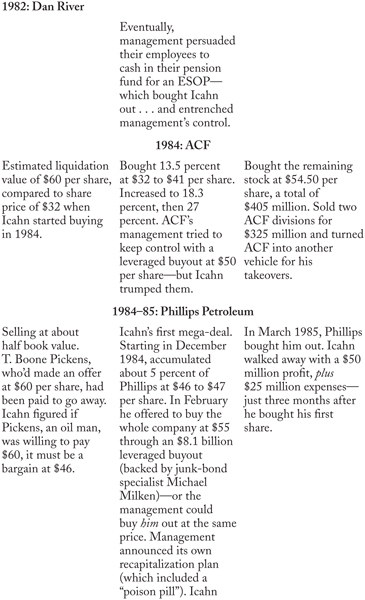

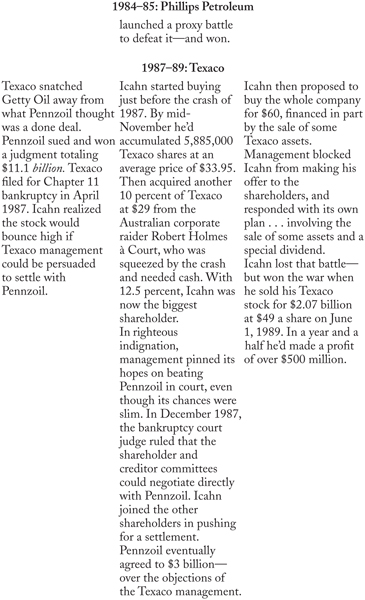

As the following table clearly demonstrates, Icahn’s system—like those of Buffett and Soros—shares all twelve elements of the complete investment system.

Taking Control

Icahn’s second target, after Tappan, was Baird and Warner, a real estate investment trust (REIT) which traded at a discount of at least 57.5 percent to its liquidation value.

As with Tappan, after he’d built his stake, he sought a seat on the board, but was rebuffed with the comment, “What do you know about the real estate business?”

Positioning himself as “just another shareholder,” he launched a proxy battle—but this time for control, knowing that the REIT’s real estate holdings could easily be turned into cash. By highlighting that management had paid itself hundreds of thousands of dollars in fees while skipping a dividend to shareholders—and vowing that, if he won, neither he nor his companies would take penny in fees or salary—he won the vote and moved into the driver’s seat.

Very quickly, he sold off the real estate and turned the now cash-rich Baird and Warner into one of his takeover vehicles. The shareholders who stayed on board made piles of money.

Icahn’s Margin of Safety

Baird and Warner investment is a good illustration of how Icahn protects himself from the risk of loss. When he began buying it at $8.50 a share, it was trading at a nice discount to its book value of $14. But Icahn and Kingsley figured that its liquidation value was, conservatively, at least $20, which gave him a huge, built-in margin of safety.

And in the worst case, as he was buying real estate at over 50 percent off, he was getting double the average rental yield at the time.

But not every one of his investments worked out so well. USX—formerly United States Steel—was his fifteenth (and last) investment in the takeover era of the 1980s. And in this instance, the management had his measure and was immune to his tactics. Indeed, after he’d built a 13.5 percent stake and took his case for restructuring the company to the shareholders in a proxy battle, he lost to management!

In 1991, after five years of sparring with the USX management, Icahn finally agreed to a standstill agreement that basically tied his hands. So he quickly dumped his stock for a mediocre profit. In this case, he probably would have been better off putting his money in T-bills.

From this experience Icahn realized that the takeover era of the 1980s had come to an end. Company managements had woken up to the dangers they faced from takeovers and leveraged buyouts by people like Icahn, T. Boone Pickens, Michael Milken, and Kravis Kohlberg Roberts. So they’d erected powerful barriers, such as staggered boards and poison pills, to deter the raiders.

What’s more, the investment firm Drexel Burnham Lambert had gone belly up, so the source of much of the capital that fueled these corporate raids disappeared. And the rising stock market made bargains harder and harder to find.

Icahn realized it was time for him to step back and wait for the market to swing back in his favor.

Which it did. Indeed, the ten years from 1994 to 2004 were Icahn’s best. During the period he compounded his wealth at the staggering rate of 50.5 percent5 per year!

In one of his forays, he took a 5.6 percent stake in RJR-Nabisco with the aim of creating value by splitting the company into its tobacco and food components. In 2000 Icahn swooped on the Sands Casino in Atlantic City, which had been in bankruptcy for two years and could be bought for a song. Learning from his experience with TWA, he invested wisely in upgrading the casino, turning it into a money spinner.

Icahn’s Biggest Mistake

Like Buffett, Icahn avoids major mistakes by sticking to his criteria. But when he does make a mistake, it can sometimes take him a while to realize it, admit it, and take action to correct it.

The best example is his investment in TWA, which he bought into in 1985. TWA met most of his criteria—it was undervalued, and there was no controlling shareholder. But it did not meet his criteria as a potential takeover candidate: The only companies likely to be interested in buying TWA were other airlines, and most of them were in the same cash-poor boat.

Eventually another bidder did appear: Frank Lorenzo of Texas Air. His initial offer of $22 a share—which Icahn managed to push up to $26—did offer a nice premium to Icahn’s entry price of $18 per share. But by then—in a departure from his system—Icahn had already decided to take over the entire company and run it himself.

Ownership of an airline, or newspapers, TV stations, and sports teams, can be an ego-boosting experience. And Icahn had “fallen in love” with the idea of running an airline—violating the habit of being emotionally involved in the process of investing, not the investment itself.

By taking control, he had also violated his investment system and sailed into uncharted waters.

TWA may have been undervalued, but it was not like an undervalued REIT, which can easily be liquidated at a profit. For example, you could sell one plane at a good price, but if you tried to unload 50, there’d only be buyers at a massive discount.

Worse, TWA was a poorly managed company in a lousy industry. To remain competitive it needed a massive investment in new planes and equipment. But Icahn’s style was typically to take money out of the company, not put money in.

And Icahn did eventually succeed in getting his money out. First by using TWA’s cash flow to help finance his bids for Texaco and USX. And then, in 1988, by arranging a leveraged buyout, financed with junk bonds, which gave him his all initial investment back and ownership of 90 percent of the restructured TWA.

Clearly Icahn’s negotiating skills served him well once again.

However, aspects of this deal came back to haunt him. The airline needed massive investments in new planes and equipment to keep flying. Instead, Icahn had milked the company of its cash and left it saddled with enormous debts.

He’d got his money back, but there was an important factor he had overlooked. By owning more than 80 percent of TWA, Icahn could be held liable for the company’s future pension obligations—potentially $1.2 billion.

When TWA subsequently sought Chapter 11 protection in 1992, the federal Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation sought to hang Icahn with this liability.

Once again he negotiated his way out. Without an injection of money—$200 or $300 million—TWA would have had to shut down totally and stop flying. The unions would have been left with the satisfaction of stiffing Icahn, but without jobs.

Political pressure to save TWA’s thousands of jobs was a factor Icahn used to great advantage in persuading the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation to give way.

But he did have to lend TWA $200 million to keep it flying.

This was a powerful lesson for Icahn: When you take control of the business, if you’re not going to liquidate it, you have to be prepared to run it and invest money in it.

It’s a lesson he has used to expand his investment system, using his proven takeover strategy to occasionally target a company—like the Sands Casino or XO Communications—that he would like to own and knew he could run successfully.

Cleaning Up After the Dot.Com Boom

The collapse of the Internet boom also produced a swath of situations tailor-made for Icahn. His skill in identifying undervalued bargains led him to make a bid for Global Crossing and grab up companies like XO Communications, which still had valuable assets but had been dragged under in the collapse and could now be had for pennies on the dollar.

Throughout his career Icahn has single-mindedly focused on his investment endeavors. For example, his wife has complained more than once that she never sees enough of him. One reason: After she goes to bed he goes to his office at home and starts a second working day!

Contemptuous of slothful managers running underperforming businesses at half throttle, Icahn’s overriding motivation has always been to “shake up the establishment.” As with Buffett and Soros, the money he makes is secondary for him. He enjoys the thrill of the chase.

And, indeed, Icahn shows no sign of slowing down. In 2004, at the tender age of sixty-eight, when most ordinary people are polishing their golf clubs, and with $7.6 billion already in his pocket, Icahn announced he was setting up a $3 billion hedge fund. Seeded with $300 million of his own money, he invited investors who’d like to put up $25 million or more to join him.

John Templeton: The Global Bargain Hunter

“If you are really a long-term investor, you will view a bear market as an opportunity to make money.”

—JOHN TEMPLETON6

Sir John Templeton, now ninety-two years old, became a legendary investor by loading up on cheap stocks in emerging markets like Japan and Argentina for his Templeton Growth Fund back in the 1950s and 1960s—long before the concept became a commonplace.

But his first major investment was in the United States. In 1939, figuring war would bring the ten-year-old Great Depression to an end, Templeton bought around $100 worth of every stock on the major American stock exchanges trading under $1. He bought 104 stocks in all—including, he insisted to his broker, those in bankruptcy.

Four years later, some of the companies Templeton had invested in had gone out of business. But many others had gone up, some by as much as 12,500 percent! Overall, he’d turned his original investment of $10,000 into $40,000 (over a million in today’s dollars), an increase of 41.4 percent per year.

Applying Graham’s Principles

If this strategy sounds familiar, that’s because it is. It was based on Benjamin Graham’s principles. Indeed, in the 1930s, Templeton attended a course in securities analysis given by Graham. Just like Buffett, Templeton developed his own unique variant of Graham’s basic system.

Templeton’s first major investment was typical of the investments he would make throughout his lengthy investment career:

Only Buy Bargains. Ignore the popular stocks, the ones that are owned by institutions and followed by Wall Street analysts. Do your own digging to find stocks that few people are interested in.

But Templeton also cast his net far wider than Graham had, or Buffett ever would, searching all over the world for companies he could buy for a fraction of their real worth. He wasn’t just looking for bargain stocks; he wanted the best bargains in the world.

Buy in Bear Markets. The best time to buy is when the market is down and most investors—including the professionals—are too scared to invest.

Like Buffett, and Graham before him, Templeton would only invest when he could be sure of having a large “margin of safety.” The time you’re most likely to be able to get that is when the market is on its knees.

In this respect he is like Buffett, who will go on a spending spree when stock markets collapse—and at other times has to wait patiently for months or more to find an investment that meets his criteria.

By taking a global view, Templeton knew that he could almost always find a bear market somewhere in the world.

Invest Actuarially. Focus on a narrow segment of the market and within that class of investments, following Graham, buy a range of stocks that fit your criteria. Some of these may end up losing money, but the winners will more than offset the losses.

Invest with a “Trigger.” Templeton looks for an event—such as the advent of the Second World War, which ended the Great Depression and signaled the beginning a new boom—which will change the fortunes of his investments.

Rarely are such triggers as clear-cut. Most of Templeton’s success results from following his belief that markets move in cycles, that inevitably a bear market will follow a bull market, and vice versa. The trigger, then, is the inevitable change in the market’s direction.

These are the basic elements of the investment strategy that he followed—with much refinement—over the next fifty-three years.

With one exception: For his first major investment back in 1939 Templeton used 100 percent leverage. He didn’t have $10,000, so he borrowed the entire amount!

“The World’s Markets Are Interconnected”

John Templeton was born in a small town in Tennessee in 1912. His family was comfortable but not exceptionally well off. In his second year studying economics at Yale, the Great Depression set in and his father told him he could no longer finance his education.

So Templeton was forced to work his way through his final years at university. As a result, he learned to appreciate the value of a dollar, being forced by necessity to shop around for the best bargain for every purchase he made—including food, clothing, furniture, and accommodation. He managed to stretch his budget, making every dollar do the work of two. This became a lifetime habit.

And it didn’t affect his studies. He graduated with flying colors, even winning a Rhodes scholarship to Oxford.

He became interested in stocks while at Yale, observing, like Graham, that stock prices fluctuated wildly while the underlying value of the businesses was far more stable.

At Oxford, though he was studying law, he “was really preparing myself to be an investment counselor, particularly by studying foreign nations.”7 So he took the opportunity to travel widely around Europe and Japan, visiting thirty-five different countries altogether.

His viewpoint—commonplace now, but highly unusual in the 1930s—was that the world’s investment markets were interconnected. To be a successful investor it wasn’t enough to understand a company’s market and competitors on its home turf: You needed an appreciation of how foreign companies and economies might affect that company’s destiny.

When Templeton returned to the United States, he joined Merrill Lynch’s new investment counseling division in New York. And in 1940 he established his own counseling firm.

The initial period was tough going. By the end of the Second World War he still had only a handful of clients, but his results were evidently excellent. Word of Templeton’s abilities spread, money started pouring in, and in 1954 he set up the first global investment fund.

Getting Time to Think—Tax-Free

Eventually his firm grew to be managing $300 million. Templeton found himself so busy with the day-to-day running of the business that he felt he didn’t have enough time to think. Like Soros, he believes that to be a successful investor you need to have the time to stop and contemplate what’s going on.

But rather than delegate more of his responsibilities, in 1968 he decided to make a clean break. He sold out to Piedmont Management and at the age of fifty-six basically started all over again with only the Templeton Growth Fund, which Piedmont didn’t want.

He left the United States, moving from Wall Street to the far more relaxed lifestyle of the Bahamas. What’s more, after giving up his U.S. citizenship and becoming a British subject, he could live there tax-free. This move would later save him around $100 million in taxes, when he sold his family of mutual funds to Franklin Group in 1992.

From November 1954, when he started the Templeton Growth Fund, until Franklin bought him out, he achieved an annual compound return of 15.5 percent. During the same period the Dow Jones Industrials rose by only 5.8 percent a year.

Even more impressive than its performance when making money was his fund’s record in bear markets. According to one study, in the twenty years to 1978, the Templeton Growth Fund was consistently ranked in the top twenty of four hundred funds in rising markets. But its performance leapt to the top five in declining markets, demonstrating how Templeton had managed to achieve the number one objective of every successful investor: preserving your capital before worrying about how you’re going to increase it.

Loading Up on Cheap Japanese Stocks

Instrumental in Templeton’s success was his prescient move in the late 1960s to begin investing heavily in Japan. He noticed that there were bargains galore on the Tokyo stock exchange.

At that time, Japan was known worldwide for its cheap and shoddy products. But Japanese stocks were even cheaper, with great companies that investors hadn’t even noticed selling, on average, for just three times earnings. While American stocks were then trading at fifteen times earnings.

The Spiritual Investor

Templeton views his money as a “sacred trust” that he can use to help other people.

In 1987 he established the John Templeton Foundation with the aim of spurring “spiritual progress.” He established an annual $1 million award for achievements in religion. Recipients have included Mother Teresa and Billy Graham.

He has always felt that the spiritual side of life was crucial to everyone’s well-being. As an investment counselor, his view of what he was doing wasn’t that he was making piles of money, but that he was helping people be in a position to achieve their goals—both material and spiritual.

But Templeton didn’t just want bargains. He wanted quality bargains. So he scoured the Japanese market for soundly managed companies with promising products and projected growth rates of at least 15 percent a year. As soon as he found one, he’d immediately start buying. He bought stocks like Hitachi, Nissan, Matsushita, and Sumitomo.8 Companies that today are household names but back then were hardly known outside of Japan.

He poured so much money into the Tokyo market that by the time he’d finished buying, he’d put over 50 percent of his fund’s assets into these “made-in-Japan” bargains.

Clearly, Templeton knew a bargain when he spotted one and wasn’t shy about buying as much as he could.

Tokyo stocks peaked on New Year’s Eve, 1989, with stocks selling for as high as 75 times earnings. The bear market that followed has still not come to an end.

But Templeton was out long before. As he admits himself, he sells too soon. He was completely out of the Japanese market by 1986, when stocks were going at “just” 30 times earnings.

His exit rule is to sell a stock when he finds a new bargain to buy. For example, in 1979 Nissan’s stock price had risen so far it was selling at 15 times earnings, while in the United States, Ford was going for just 3 times earnings. So to Templeton, Ford at that point was the far better buy.

He is constantly monitoring his portfolio, measuring the valuation of the stocks he owns against those of others he is researching. When he finds a new bargain, he’ll take profits and redeploy his capital.

Templeton’s Criteria

Templeton has a hundred-odd different factors he examines for investing in a company—though not all of them will be relevant in each case.

But four factors, he says, are always crucial to measuring the profit expectancy of an investment:

1. The P/E ratio

2. Operating profit margins

3. Liquidating value

4. The growth rate, particularly the consistency of earnings growth9

One way he used to investigate these criteria was to visit the companies. But when he moved to the Bahamas, determined not to slip back into a situation where he didn’t have time to think, he began grooming managers who could follow his investment principles and take over the investment decision making.

As part of their training, he sent them out to visit managements with a standardized questionnaire in hand. He had developed and honed the questions over his first three decades as an investment manager.

Today the various Templeton Funds continue to be managed by his protégés, including Mark Mobius and Mark Holowesko. Both have become famous in the fund management industry in their own right, continuing to use the same tools and techniques that Templeton pioneered. Mobius, for instance, will not invest in a company that hasn’t been visited by him personally or by a member of his investment team.

Templeton’s Greatest Coup

Though Templeton sold his fund company in 1992 to devote more time to his charitable and spiritual pursuits, he still kept his eye on the markets.

In 2000, at the tender age of eighty-seven, Templeton made a brilliant and enormously profitable foray back into the stock market—and proved that even if you can’t teach an old dog new tricks, that old dog can certainly use his old tricks in new ways.

Like most other value investors, Templeton was flabbergasted as dot-com stocks zoomed to absurdly high levels. Many investors, realizing these stocks were wildly overvalued, shorted them all the way up—selling shares they didn’t own expecting to be able to buy them back cheaper.

But the market was like a speeding train: Nothing could stop it from going higher. So some lost their shirts. Others, like Julian Robertson, eventually couldn’t bear the pain anymore; he quit in disgust, shutting down his fund entirely.

Not Templeton. He bided his time until January 2000—three months before NASDAQ peaked—when he discovered a trigger that allowed him to initiate one of the most creative short-sale strategies ever.

The venture capitalists and insiders who floated these Internet companies were typically restricted from selling their stock until six months or a year after the company had gone public.

Templeton’s insight was to use the end of this lockup period as his trigger. He systematically initiated short positions in eighty-four different dot-com companies eleven days before the lockup period for each stock expired. He projected that the increased supply of stock from insiders rushing to cash in their “lottery tickets” would drive prices for these stocks down.

Did it ever. Many he bought back when they reached just 5 percent of the price he’d sold them at. And following his normal rule of “getting out early,” some he bought back when they’d dropped to thirty times earnings.

Eighteen months later, he’d added $86 million to his net worth.10 Not bad for an old codger.

Bernhard Mast: “Minting Gold” in Hong Kong

“First of all, you have to protect yourself from yourself”

—BERNHARD MAST*

I first met Bernhard in Hong Kong when I was testing my Investor Personality Profile,† which pinpoints your weaknesses and strengths as an investor. From his answers to the questionnaire I could clearly see that he was following all the Winning Investment Habits—except one. Which puzzled me. He didn’t appear to be following Habit No. 11—which is to act instantly once you have made up your mind to buy or sell something.

So I queried him about this, wondering if there was some flaw in the format of my questions.

He told me that he reviews his portfolio and makes his investment decisions in the morning but he places all his orders through a bank in Switzerland. Due to the time difference, Bernhard can’t phone his orders in until afternoon in Hong Kong, when Zurich opens for business.

As I got to know him and understand his strategy, it became clear that he was, indeed, following all 23 Habits.

Bernhard is living proof that you don’t need to be a high-profile investor with hundreds of millions of dollars, or even an investment professional, to successfully apply the Winning Habits.

What’s more, he has no ambition to have his name up in lights like Buffett or Soros. He doesn’t want to manage other people’s money and prefers to remain anonymous. His goal is very simple: “When I’m seventy-five, I don’t want to be stacking shelves at a supermarket to earn money to put food on my table. I’ve seen it happen to others, and it’s not going to happen to me,”11 he told me.

What he sees as the greatest threat to his future financial security is the loss, over time, in the purchasing power of paper currencies. As he points out, a dollar today buys less than 5 percent of what a dollar bought a hundred years ago. In contrast, the purchasing power of an ounce of gold has remained relatively constant.

This is a topic Bernhard has studied in detail. He even wrote his PhD thesis at the University of St. Gallen on central banks and their gold reserves (though as he got an exciting job offer in Asia he never actually handed in his thesis). He’s fascinated by the history and theory of money. And today his knowledge in this field forms the basis of his investment philosophy.

His first investment was in silver in 1985. He recalls going on holiday and not even reading a newspaper for ten days. In a taxi on the way to the airport to catch his flight home, he noticed in the newspaper that silver had gone up 20 percent. He took his profits right away.

The Investment “Genius” Gets Wiped Out

Bernhard was, at that time, just dabbling in the markets. His main focus was on building his business. He told me he didn’t make another significant investment until 1992. A friend of his worked on the trading desk of one of the big Swiss banks. Together, they went heavily into silver call options, buying $60,000 worth. Soon after they’d gone into the market, the price of silver soared. They made ten times their money!

“We felt like geniuses,” Bernhard recalled.

So what happened next, I wanted to know. They tried to repeat their success by shorting the S&P index. But American stocks didn’t fall; they began to creep up. Being “genuises,” Bernhard and his friend added to their short position, only to see the market go through the roof. “I was wiped out,” Bernhard told me. “I gave back all my profits on the silver options, plus my original investment—and then some.”

It was then Bernhard realized that, to invest successfully, the first thing he had to do was “protect myself from myself.”

Devising the Rules

Bernhard sat down and did something very few people ever do. He spent several months building a detailed investment strategy, and more time testing it, so he could achieve his primary aim: ensuring he would have financial security and independence for the rest of his life.

He defined his overriding investment objective as preserving the purchasing power of his capital. He believes the safest way to achieve this goal is with investments in precious metals, chiefly gold.

Bernhard divided his assets into four parts: life insurance, real estate, fully owned gold bullion, and a trading portfolio consisting of mining stocks and forward positions in precious metals.

He keeps them all separate, even to the extent of using different banks for the mortgage on his property and for storing his gold bullion.

The first three asset classes are the bedrock of his financial security. His aim in his trading portfolio is to make profits he can use to increase his ownership of gold.

Bernhard thinks that commodities, including gold, are currently undervalued. And this is the basic premise of the investment system he has devised.

Getting Leverage on Gold

Bernhard owns gold, but as gold pays no interest, his holdings don’t increase over time. To achieve that objective, he seeks to use the leverage of gold mining stocks, which he says “typically rise by a factor some two or three times the corresponding rise in the gold price.”

He has developed a complete investment system with detailed criteria for selecting mining stocks to buy.

His first screen is location. He refuses to invest in any company operating in Russia or China. Or places like Zimbabwe, Mongolia, and Indonesia. Why? “I simply don’t trust these markets,” he says. “Property rights in these countries just plain aren’t secure. They’re riddled with corruption; and governments do whatever they feel like.”

Bernhard is justifiably afraid that he could wake up one morning and learn that the mines of a company he owns have been shut down or confiscated, leaving his shares worthless. For him, investing in any of these countries is simply not worth the potential risk of loss.

Next, Bernhard looks at currencies. When I interviewed him in June 2004, he owned no mining stocks in Australia or South Africa—two of the world’s major gold producers. The reason: Both the Australian dollar and South African rand had risen dramatically against the US dollar.

“I had some South African gold shares until about a year ago,” Bernhard told me, “but I got out when I realized they can’t make any money. Even though they’re sitting on tons of gold, since the rand has skyrocketed against the dollar, they can’t take it out of the ground at a profit.”

His next filter is management. Like Buffett, he wants to be sure that management treats the shareholders well. He wants to invest with managers who’ve successfully found and developed deposits in the past. He also reviews the company’s current projects to evaluate their prospects.

Bernhard gathers all this information using the Internet. “You couldn’t have done this five years ago,” he says. “But now, there’s an enormous amount of information readily available.” Company websites provide annual reports, financial data, press releases, and the like. Stock price data is readily available, as are charts of past prices, which to him are useful tools.

The Importance of Position Sizing

Forty-seven stocks from a universe of some 350 that he has screened meet all his criteria. Following the typical actuarial approach, he owns them all, but he doesn’t have an equal investment in each. His capital allocation hinges on his assessment of where the company is in the development cycle.

To him, mining stocks fall into three categories:

• producing companies that typically pay dividends;

• companies which have proven discoveries they’re still in the process of developing, often in partnership with one of the majors like Newmont Mining; and,

• pure exploration companies, which are just as likely to burn up all their cash as they are to strike it rich with a big discovery.

Bernhard feels that companies in the second category—those nearing production—offer the best risk-reward trade-off. They’re about to turn from consumers of cash to significant cash generators. So his portfolio is weighted heavily toward this category.

And—at the moment—he gives the smallest weighting to the existing producers, as he feels they offer the least leverage on the price of gold.

“The Best Financial Decision I Ever Made”

“Moving to Hong Kong was the best financial decision I ever made,” Bernhard told me. “The tax rates are so low I can compound my money faster here than just about any other place in the world.”

When he first moved there it was to accept an attractive job offer. Tax rates were the last thing on his mind.

He also admits that having no children has saved him a small fortune, giving him far more capital to invest—and compound.

And in a city with more Rolls-Royces per capita than anywhere else in the world, Bernhard doesn’t even own a car. “Why have a car in a place where the buses are great and taxis are cheap and plentiful.”

He also has detailed rules about timing his purchases and sales of these stocks.

He will only buy stocks that meet his criteria when gold is under $350 per ounce. “Following this rule,” he told me, “I’ve bought hardly anything over the past six months.” Only if gold dips below $350 would he add to his stock holdings.

When one of his stocks doubles, he sells half, getting his initial investment back. As a result, he says, “about a third of my stocks I own for free.”

Another exit rule is to begin banking his profits if gold goes over $450 an ounce. If gold rises as he expects, sometime over the next few years he will have sold all his mining stocks and will be looking for some other investment field.

He spends three hours a day looking at political and economic developments that could affect his assets; searching for new candidates to add to his list of qualified stocks; and monitoring the stocks he already owns to ensure they continue to meet his investment criteria. If they don’t, he dumps them.

Bernhard pays cash for his stocks, and then uses them as collateral to finance forward purchases of gold bullion, which is the second element of his trading strategy.

If gold rises above $450 per ounce, he will begin cashing in his stock profits. He will take that money and use it to take delivery of the gold he has purchased with forward contracts. This bullion he adds to his nest egg of precious metals.

To protect himself against a catastrophic drop in the price of gold and avoid being wiped out, he has stops set to liquidate his entire trading portfolio. Moreover, he has a large cushion of protection. “I have my gold position at an average price of around $310 an ounce,” compared to the current price of $408, “so gold has to drop a long, long way before I have to worry.”

His overall approach is exceptionally conservative. Unlike the average homebuyer, who’ll increase his mortgage to gain spending money when the price of his house goes up, Bernard doesn’t even count unrealized gains when he values his holdings.

The only profits he counts as part of his net worth are the ones he has actually cashed in. And while he doesn’t include paper profits, he does subtract paper losses. In other words, he values his portfolio at his cost, or the market price—whichever is lower.

“Investing Is Like Playing Chess”

Bernhard’s underlying premise is that commodities are undervalued. Eventually they’ll be fully valued. So he recognizes his current system will stop working someday.

Indeed, he fully expects that some time in the next five to ten years he will have sold all his mining stocks, taken delivery of his gold forward contracts, and possibly even sold some of his bullion nest egg.

“Investing is like playing chess. You have to contemplate the present, but you also have to look ahead to the forth, fifth, sixth, or seventh move.” So he’s already looking at expanding his universe into energy stocks, a field where he’s beginning to test a variation of his system.

Like the well-known investors we’ve already talked about, Bernhard has devised a system which has all twelve necessary elements. And like their approach to investing, his is highly personalized and specialized, clearly drawing on his own unique background, his studies, his experience, and interests.

“Some of my friends think I’m crazy,” Bernhard says. “But I’m very happy with my current strategy, and I sleep very well every night.

“I follow it,” he told me, “because it’s the safest way I know of, right now, to preserve the purchasing power of my capital. If I knew a better way, I’d do it. I’d switch today.”

While his method is certainly unusual, it works for him. And he follows it religiously. To ensure he doesn’t deviate from it, he keeps a written set of guidelines—his rules—and continually refers to them.

He admits that he does occasionally make a mistake. “And if you do,” he said, “don’t panic! If you panic, you freeze up, you become your own worst enemy. I just say to myself, ‘Oops,’ review what I did dispassionately, and take the necessary action.”

He told me he reviews his list in detail every six months, evaluates his actions to ensure he’s been following his rules, and sees if he’s learned or discovered something that could improve them.

Such rigor and dedication is unusual in any field. But it is what has made Bernhard—like Buffett, Soros, Icahn, and Templeton—a highly successful investor.