3

Keep What You Have

“Rule No. 1: Never lose money.

Rule No. 2: Never forget Rule No. 1.”

—WARREN BUFFETT

“Survive first and make money afterward.”

—GEORGE SOROS1

“If you don’t bet, you can’t win.

If you lose all your chips, you can’t bet.”

—LARRY HITE2

GEORGE SOROS WAS BORN GYÖRGY Schwartz in Budapest, Hungary, in 1930. Fourteen years later, the Nazis invaded.

Strange as it may seem, Soros describes the twelve months of Nazi occupation as the happiest year of his life. Every day was a new and exciting—and risky—adventure. For a Jew in Nazi-occupied Hungary, there was only one penalty for discovery: death. Soros had just one aim: survival. An aim that has stayed with him for the rest of his life, and is the cornerstone of his investment style.

That the Soros family did not end up in one of the Nazis’ death camps can be attributed to the survival instincts of Soros’s father. Years later, Soros wrote in The Alchemy of Finance:

When I was an adolescent, the Second World War gave me a lesson that I have never forgotten. I was fortunate enough to have a father who was highly skilled in the art of survival, having lived through the Russian Revolution as an escaped prisoner of war.3

Tivadar Soros had been captured by the Russians while fighting in the Austro-Hungarian army during the First World War and was sent to Siberia. He engineered a breakout from the prison camp, but the Russian revolution had led to civil war. Reds, Whites, bandit gangs, and roving units of foreign troops were killing each other—and any innocent bystanders who got in the way.

For the three dangerous years it took him to get back to Budapest, Tivadar Soros had only one objective: survival. And he did whatever he had to do to survive, no matter how abhorrent.

His stories of those times fascinated young George. As a child, George recalled, “I used to meet him after school, and we would go swimming. After swimming, he would tell me another installment of his life story. It was like a soap opera that I absorbed totally. His life experience became part of my life experience.”4

At the beginning of 1944 it was clear that the Germans were going to lose the war. Russian troops were advancing from the east; the Allies had a foothold in Italy. In March, Hungary, which had been Hitler’s ally since the beginning of the war, tried to find some way of coming to terms with the winning side. So the Nazis invaded to plug a potential hole in their Russian front.

Hungary’s was one of the few remaining Jewish communities in Central Europe. But that began to change the day the Nazis arrived.

Like many other Jews in Europe, some of Hungary’s Jews thought the Nazis would never invade; or they refused to believe the rumors of the Auschwitz death camps. And when the Nazis came, they thought “it couldn’t happen here” or that the war would be over in just a few weeks anyway so it wouldn’t matter.

Tivadar Soros thought differently.

He had shrewdly liquidated most of his property in the years before the Nazi invasion. That was a smart move, as the Nazis and their Hungarian collaborators quickly confiscated all Jewish assets. He bought false papers for his family; for the rest of the war George Soros became Sándor Kiss,5 his elder brother Paul began “a new life under the name of József Balázs,”6 and his mother was disguised as Julia Bessenyei.7 By helping the Jewish wife of a Hungarian official, Tivadar arranged for George to pose as his godson, while he established different hiding places for each member of the family.

It was a harrowing year for the Soros family. But they all lived.

“It was my father’s finest hour,” according to Soros,

because he knew how to act. He understood the situation; he realized that the normal rules did not apply. Obeying the law became a dangerous addiction; flaunting it was the way to survive.… It had a formative effect on my life because I learned the art of survival from a grandmaster.8

Soros concluded: “That has a certain relevance to my investment career.”9

What an understatement! In the markets, survival translates as Preservation of Capital. The very foundation of his investment success was laid in that year of the Nazi occupation of Hungary when Soros learned, from a grandmaster, how to survive in the face of the gravest possible risk.

Billions of dollars later, when it was clearly no longer an issue, “he talked all the time about survival,” his son Robert recalled. “It was pretty confusing considering the way we were living.”10

Soros admits he has “a bit of a phobia” about being penniless again—as he was at seventeen. “Why do you think I made so much money?” he asks. “I may not feel menaced now but there is a feeling in me that if I were in that position [penniless] again, or if I were in the position that my father was in in 1944, that I would not actually survive, that I am no longer in condition, no longer in training. I’ve gotten soft, you know.”11

To Soros an investment loss, no matter how small, feels like a step on the road back to the “bottom” of his life, a threat to his survival. As a result, I conclude (though I cannot prove) that George Soros is even more risk-averse than Warren Buffett, hard as that may be to accept.

* * *

Warren Buffett was born halfway around the world from Budapest, in the sleepy—and peaceful—town of Omaha, Nebraska, in the same year as George Soros, 1930.

His father, Howard Buffett, was a securities salesman at Union Street Bank in Omaha. In August 1931—just two weeks before Buffett’s first birthday—the bank collapsed. His father was jobless and broke, as all his savings disappeared along with the bank.

Howard Buffett quickly rebounded to open a securities firm. But the middle of the Great Depression was a tough time to sell stocks.

Just as the Nazi occupation of Hungary was a formative experience for the young George Soros, so those early years of hardship seem to have imprinted Warren Buffett with an abhorrence of parting with money.

He’s lived in the same house since 1958, which he bought for $31,500. His only concession to his wealth is the addition of a few rooms and a racquetball court. His salary from Berkshire Hathaway is a mere $100,000 a year, making him the lowest-paid CEO of any Fortune 500 company. He would rather eat at McDonald’s than Maxim’s de Paris; and he buys his favorite drink, Cherry Coke, by the caseload—after scouring Omaha for the lowest price. Just like any housewife watching her budget.

Buffett has saved nearly every penny he’s ever made … from the age of six when he started selling Cokes door to door, right up to today when the idea of selling even one of his shares in Berkshire Hathaway is unthinkable.

For Buffett, money once made is to be kept, never lost or spent. Capital preservation is the foundation of both his personality and his investment style.

“Never Lose Money”

Warren Buffett was a Depression baby. His young personality coalesced around a deep desire to become very, very rich.

In elementary school, as in high school, he would tell his classmates that he would be a millionaire before he was thirty-five. When he turned thirty-five, his net worth exceeded $6 million.

Once, when asked why he had this drive to make so much money, he replied: “It’s not that I want money. It’s the fun of making money and watching it grow.”12

Buffett’s attitude towards money is future-oriented. When he loses—or even spends—a dollar, he doesn’t think of the dollar, but what the dollar could have become.

[Buffett’s wife] Susie … was a virtuoso shopper. She dropped $15,000 on a home refurnishing, which “just about killed Warren,” according to Bob Billig, one of his golfing pals. Buffett griped to Billig, “Do you know how much that is if you compound it over twenty years?”13

This attitude toward money permeates his investment thinking. For example, at the 1992 Berkshire annual meeting he said: “I guess my worst decision was that I went into a service station when I was twenty or twenty-one. And I lost 20 percent of my net worth. So that service station’s cost me about $800 million now, I guess.”14

Counting a Loss

When you or I lose money, we count the dollars we actually lost. Not Buffett. His loss is what those dollars could have been. Losing money, to him, is a gross violation of his underlying aim, which is to “watch money grow.”

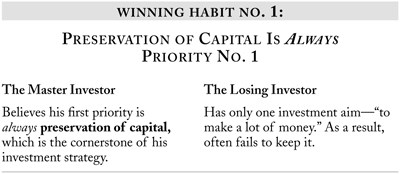

Preservation of capital is an investment rule propounded by many but practiced by few.

Why?

When I ask investors how it would feel to make preservation of capital their first priority, most report a sense of paralysis, a feeling that “I’d better not do anything because I might lose money.”

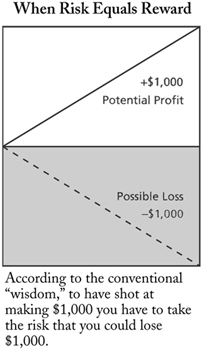

This reaction reflects the Fifth Deadly Investment Sin: the belief that the only way to make big profits is to take big risks. It implies that the only way to preserve capital is to take no risk at all. So never taking a risk guarantees you’ll never make any giant profits.

For people who take this view, profits and losses are related as if they were flip sides of the same coin: To have the chance of making a dollar you have to take the risk that you’ll lose that dollar—and maybe more.

High-Probability Events

In the common view, the aim of capital preservation is to not lose money. It’s seen as a restrictive strategy, one that limits your options.

But the Master Investor is focused on the long term. He does not view each investment he makes as a discrete, individual event. His focus is on the investment process, and the preservation of capital is the foundation of his process. It’s built into his investment method; it underlies everything he does.

This doesn’t mean that whenever the Master Investor considers an investment his first question is: How am I going to preserve my capital? Indeed, at the moment of decision, of making an investment, that question may not even occur to him.

When you’re driving, your focus is on getting from point A to point B, not on staying alive. That objective, however, underlies the way you drive. For example, I have a rule to keep a certain distance from the car in front, the distance varying with speed. Following the rule lets me brake to a stop if I need to without hitting the car in front, avoiding danger to life or limb. Following this rule means survival. But when I’m driving I don’t think about all that. I just keep my distance.

In the same way, the Master Investor doesn’t need to think about preservation of capital. By focusing on his investment rules he automatically preserves his capital, just as I stay alive by focusing on keeping my distance while I’m driving.

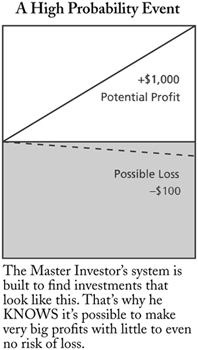

No matter what his personal style, the Master Investor’s method is designed to find one thing only: what Buffett calls “high-probability events.” He invests in nothing else.

When you invest in a high-probability event, you are almost certain to make money. The risk of loss is tiny—and sometimes nonexistent.

When capital preservation is built into your system, these are the only kinds of investments you will make. That’s the Master Investor’s secret.

“I Am Responsible”

The Master Investor accepts that he is responsible for his results. When he takes a loss he doesn’t say, “The market went against me” or “My broker gave me bad advice.” He says to himself, “I made a mistake.” He accepts the result without recrimination and then analyzes what he did or didn’t do so that he won’t repeat the mistake. And moves on.

By taking responsibility for both his profits and his losses the Master Investor stays in command of himself. Like the expert surfer, he doesn’t believe he commands the waves. But by being both experienced and in control of his own actions, he knows when to ride a wave and when to avoid it … and so rarely gets “dumped.”

Can You Make It Back?

At many investment seminars I’ve asked the audience: “Who has lost money in the markets?” Just about everybody’s hand goes up.

I then ask: “And how many of you made it back—in the markets?” Almost nobody’s hand stays up.

To the average investor, investing is a sideline. When he takes a loss, he subsidizes his portfolio from his salary, pension fund, or other assets. He almost never makes it back in the markets.

To the Master Investor, investing is not a sideline. It’s his life—so if he makes a loss, he is losing part of his life.

Here’s why:

If you lose 50 percent of your investment capital, you have to double your money just to get back to where you started.

If you can average 12 percent a year return on your capital, it’s going to take you six years to recover. It would take Buffett about three years and two months at his average return of 24.4 percent, while at 28.2 percent Soros could do it in “just” two-and-three-quarter years.

What a waste of time!

Wouldn’t it have been simpler just to have avoided the loss in the first place?

You can see why Buffett and Soros would answer with a resounding yes. They know it’s much easier to avoid losing money than it is to make it.

The Foundation of Wealth

Warren Buffett and George Soros are the world’s most successful investors because they are both extremists at avoiding losses. As Buffett puts it, “It’s much easier to stay out of trouble now than to get out of trouble later.”

Preservation of capital isn’t just the first Winning Investment Habit. It’s the foundation of all the other practices the Master Investor brings to the investment marketplace, the cornerstone of his entire investment strategy.

As we’ll see, every other habit inevitably traces back to Buffett’s First Rule of Investing: Never lose money.