30

What Are You Going to Measure?

“If you can’t measure it, you can’t control it.”

—MEG WHITMAN, CEO EBAY1

THE LINK BETWEEN YOUR INVESTMENT philosophy, your investment method, and your investment system is your investment criteria.

From all possible good investments in your investment niche, how do you know when you have found one to buy? What makes a home run stand out from the others? It will be one that meets all your investment criteria—a detailed checklist of the characteristics of what you have defined as a good investment, against which you can measure the quality of any particular investment.

As you’ll recall, Buffett is measuring the characteristics of a good business, including the quality of the management, the nature of its franchise, the strength of its competitive position, its pricing power, its return on equity—and, of course, its price. While Soros is measuring the quality of his investment hypothesis against events as they unfold.

Your investment criteria are the features of an investment in your chosen niche that you can measure today which you know will consistently make you profits over time.

Your investment criteria give you six crucial elements of your investment system: what to buy, when to buy it, when to sell it, how much to pay, how to gauge whether everything is on track once you have invested—and what to focus on when you’re searching for investments. So you need to specify them in as much detail as you can.

Your Margin of Safety

As we saw in chapter 6, “You Are What You Measure,” a complete investment system has twelve elements. They are all bound together by the Master Investor’s highest priority: preserving capital. His method of preserving capital is to avoid risk (Habit No. 2). He accomplishes this aim by embedding his preferred method of risk control into all aspects of his system.

Buffett’s primary risk-control method is to always have what he calls a “margin of safety.” Although this term has become associated with Benjamin Graham and Warren Buffett, in fact every successful investor has his own version of the margin of safety: It’s the way he minimizes risk.

You may decide to be like Soros and discipline yourself to get the hell out the minute you find yourself in uncharted waters—sell first and ask questions later. Or you may use an actuarial approach to risk control.

Whatever margin of safety you choose, for it to work it must be one of the foundations upon which your system is built—and be woven into your system’s rules.

Applying Your Criteria

The Master Investor treats investing like a business. He doesn’t focus on any single investment but on the overall outcome of the continual application of the same investment system over and over and over again. He establishes procedures and systems so that he can compound his returns on a long-term basis. And that’s where his mental focus is: on his investment process (Habit No. 21).

Once you’re clear what kind of investments you’ll be buying, what your specific criteria are, and how you’ll minimize risk, you need to establish the rules and procedures you’ll follow to gain the Master Investor’s long-term focus.

The first step is to plan the structure of your portfolio. Will you be buying stocks? Stocks and options? Futures? Writing puts or calls, or using spreads or straddles? Investing in real estate? Is your focus on commodities, currencies, or bonds? Or would you prefer to delegate investment decision making to carefully selected money managers? These are just a few of the many possibilities you can choose from.

Having made those decisions (which, of course, might be blindingly obvious from identifying your investment niche) you need to define other elements of your system before you leap into the market.

Will you use leverage? If you’re going to invest in futures, you may think you’ll automatically be using leverage.

Not so. The use of leverage must always be a conscious and preplanned decision. If you keep the full face value of a futures contract in the account, your margin is 100 percent, the same as paying cash for a stock.

Although both Soros and Buffett use leverage, they are both cash-rich. I advise you to follow their example, focusing on the “cash-rich” part, at least until (like them) you have reached the stage of unconscious competence in your investing.

Even then, if you use leverage, follow the Master Investors’ example and use it sparingly. (And never meet a margin call.)

How are you going to minimize the impact of taxes and transaction costs? Master Investors focus on the long-term rate of compounding. One way they improve that rate is (as we’ve seen—Habit No. 6) to construct their system in a way that minimizes the taxes which need to be paid and keeps transaction costs as low as possible.

There are many different ways to achieve this. Some depend on the kinds of investments you make or on the period you plan to hold them. Where you live and where your investments are kept is another factor. If, like me, you’re an extremist on this subject, you might consider arranging your affairs so you’re liable for hardly any taxes at all.

Whatever your situation, you should use all available means to defer or reduce taxes so that your money can compound tax-free for as long as possible. By doing so, you’ll harness the power of compound interest to add several percentage points to your annual rate of return—without having to make a single investment decision.

What do you need to delegate? Unless you have a banking license and a seat on the stock (or commodity) exchange, you’re going to need to delegate some of your investment functions.

Few people think of opening a brokerage or bank account as an act of delegation. But it is: You’re hiring someone (do you know who they are?) to look after your money. Will it be there when you want it? (Banks and brokerage companies do go bust. Okay, you’re insured … but how long will it take you to get your money back?) Will you get the service and execution capabilities you require?

The wealthier you are and the more complex your affairs, the more delegation you’ll have to do (Habit No. 18). You may need to choose lawyers, accountants, tax advisors, trust companies, and other advisors.

When you buy, how much are you going to buy? When the Master Investor finds an investment that meets his criteria he buys as much as he can. His only limit is the money he has available. As a result, his portfolio is concentrated, not diversified.

By specializing in your investment niche, all your investments will come from the same category. You have already thrown the mainstream version of diversification out the window (Habit No. 5).

Nevertheless, regardless of your investment approach you will need to establish rules for what’s called “position sizing.” In other words, how much of your portfolio are you going to put into each individual investment? If the amount varies between different investments, why?

In a sense, position sizing boils down to gaining confidence in what you are doing. Once you reach the point of knowing your kind of bargain the moment you see one, you’ll be both happy and comfortable to go for the jugular.

How will you protect your portfolio against systemic shocks such as market panics? When the founders of Long-Term Capital Management developed their system, they dismissed what they called ten-sigma events as so statistically improbable that they weren’t worth worrying about.

When the Asian financial crisis of 1997 was quickly followed by the Russian debt default of 1998, LTCM was hit by two ten-sigma events in a row—and blew up.

Ten-sigma events may be improbable, but that doesn’t mean they’re impossible. The Master Investor has structured his portfolio and investment strategy so that he will survive even the most extreme market conditions.

If the market collapses overnight, will you live to invest another day? You have to structure your system so that the answer to this question is yes!

The first thing to do is to acknowledge that anything can and will happen in the markets. Generate several worst case scenarios in your mind. Then ask yourself: If any of these things happened, how would you be affected—and what would you do?

As we’ve seen, one of Soros’s protections against such systemic risk is his ability to act instantly, as he did in the crash of 1987 when even most investment professionals simply froze up.

The Master Investor’s primary protection—and this is true for both Buffett and Soros—is their judicious use of leverage. Every time the market crashes we hear stories of people who lose their shirt because they were overleveraged. The Master Investor simply doesn’t get himself into this position. You should follow his example—even if this means flouting yet another standard Wall Street maxim: Be fully invested at all times.

Hire a Master Investor?

“The average trader should find a superior trader to do his trading for him, and then go find something he really loves to do.”

—ED SEYKOTA2

To judge by the amount of money in mutual funds and with professional investment managers, the majority of people delegate the entire investment process to others.

This is a perfectly legitimate option. Investing takes time and energy, and for many of us that time and energy can be better invested somewhere else.

If this is your choice, you can still achieve superior investment returns by taking Ed Seykota’s advice and finding a successful investor to do your investing for you.

But how to judge whether a money manager is likely to be successful or not? Find a person who follows the 23 Winning Investment Habits.

It’s also important to find someone whose investment style is compatible with your personality. For example, Warren Buffett is obviously extremely comfortable having Lou Simpson manage GEICO’s investments. That’s because they share the same investment philosophy and method. By the same token, you could imagine that Buffett wouldn’t sleep very well at night if he gave money to a commodity trader—or even to George Soros himself.

To successfully delegate the task of investing means you must be clear about your own investment philosophy and preferred style. Only then can you find someone who will manage your money in the same way you would like to do it yourself.

At the very least, you need to be able to identify whether the manager has a clear investment philosophy; a complete investment system; whether the system follows logically from the philosophy; whether he’s good at “pulling the trigger”—and whether he “eats his own cooking.”

Most investors choose their money managers or mutual funds by looking at their track record or by following their broker’s or friends’ recommendations, or they are seduced by a good marketing story. None of these methods has any relationship to a manager’s long-term performance. Evaluating managers by determining how closely they follow Buffett’s and Soros’s mental habits and strategies is virtually guaranteed to improve your investment returns.

How are you going to handle mistakes? The Master Investor makes a mistake when he doesn’t follow his system, or when he has overlooked some factor that, once taken into account, means he shouldn’t have made that investment.

Like the Master Investor, you need to recognize when you may have strayed from your system and be awake to factors you might have overlooked. When you realize you have made a mistake, admit it and simply get out of your position (Habit No. 14).

Then review what led you to commit that error—and learn from it (Habit No. 15). Focus on what is under your control—your own actions.

If you’re like most people, the hardest aspects of learning from your mistakes are being willing to admit them, and then to be self-critical and to analyze your mistakes objectively.

If you overlooked something, how did that happen? Was some information “too hard” to dig up? Was it a factor you’d not appreciated the importance of before? Did you act too quickly? Were you too trusting of the management? There are a host of such errors that can be made, and the only thing you can be sure about is that you’re going to make them. Don’t take it personally; like the Master Investor, just be sure you won’t make the same mistake again.

If there was some system rule you didn’t follow, then you weren’t following your system religiously (Habit No. 13). Again, analyze why. Did you follow your heart, not your head? Did you break this rule knowingly? Did you hesitate too long?

This kind of problem should only crop up when you first set out to apply your system. It may just be that you’re at the beginning of the learning curve—or it could be that the system you have devised, or parts of it, aren’t truly compatible with your personality.

What’s crucial is that you have the mental attitude of accepting your mistakes and treating them as something to learn from.

Keep Your Powder Dry

Cash is a drag on your portfolio, says the conventional wisdom. Its returns are low and often negative after inflation and taxes.

But cash has a hidden embedded option value. When markets crash, cash is king. All of a sudden assets that were being traded at five and ten times the money spent to build them can be had for a fraction of their replacement cost.

Highly leveraged competitors go bankrupt, leaving the field free for the cash-rich company.

Banks won’t lend money except to people who don’t need it—such as companies with AAA credit ratings and people with piles of money in the bank.

In times like these the marketplace is dominated by forced sellers who must turn assets into cash regardless of price. This is when the investor who has protected his portfolio by being cash-rich is rewarded in spades: people will literally be beating a path to his door to all but give away what they have in return for just a little bit of that scarce commodity called cash.

What are you going to do when your system doesn’t seem to be working? There may be times when you lose money—even though you have followed your system religiously and you’re as certain as you can be that you have overlooked nothing.

It’s important to realize that some investment systems can and do stop working. If this appears to be the case, the first thing to do is to exit the market completely.

Sell everything. Step right back and review every aspect of what you have been doing—including your investment philosophy and investment criteria.

Maybe something has changed. Perhaps it’s you. Have you become less dedicated? Is your motivation still high? Have your interests changed? Are you distracted by some other problem such as divorce or a death in the family? Or are you simply stressed out?

More often, the cause of the change is external. Maybe your tiny niche has been invaded by Wall Street institutions loaded with capital and the margins that were once profitable have become too thin to sustain you.

The Complete System

A complete investment system has detailed rules covering these twelve elements:

1. What to buy

2. When to buy it

3. What price to pay

4. How to buy it

5. How much to buy as a percentage of your portfolio

6. Monitoring the progress of your investments

7. When to sell

8. Portfolio structure and the use of leverage

9. Search strategy

10. Protection against systemic shocks such as market crashes

11. Handling mistakes

12. What to do when the system doesn’t work

An exercise that will help you build your system is to photocopy the table here—which shows Buffett’s and Soros’s rules for each of these twelve elements—and add an extra column: Me.

You may be able to fill out some of the fields already. You’ll know you system is complete when you can fill out all twelve.

Markets can become more efficient. Is the inefficiency you were exploiting no longer there?

Have you changed your environment? Floor traders who move to screen-based trading are often surprised to discover that the system that made them money on the floor of the exchange depended upon cues such as the noise level on the trading floor or the body language of other traders. Missing those cues, they are forced to develop a different approach to regain their feel for the market.

Have you been so successful you have just got too much money to handle? That is a factor that affected both Buffett and Soros. It’s a “problem” we can all hope to have.

By considering all of these issues you’ll create an investment system that is unique to you. By taking the time to cover every one of the twelve elements in detail, you will ensure that your system is complete.

The Master Investor’s Benchmarks

Before beginning to test your system you must establish a measure that will tell you whether or not it is working. The first test, obviously, is whether or not it makes you money. But is that enough?

If your system is profitable, you’ll be getting a return on your capital. But will you also be getting an adequate return on all the time and energy you have to devote to implementing your investment strategy?

The only way to tell is to compare your performance to a benchmark.

Buffett and Soros measure their performance against three benchmarks:

1. Have they preserved their capital?

2. Did they make a profit for the year?

3. Did they outperform the stock market as a whole?

The importance of the first two is obvious. The third benchmark tells you if you’re being paid for your time; whether your system is paying you more than, say, just investing in an index fund—or leaving your money in the bank.

The benchmarks you choose will depend on your financial goals, and how you value your time. There is no “one-size-fits-all.” But only when you have established your benchmark can you measure whether your system is working or not.

Intelligent Diversification

Master Investors spurn diversification (Habit No. 5) for the simple reason that diversification can never result in above-average profits (as we saw in chapter 7).

But if all you want to do is preserve your capital, intelligent diversification is a perfectly valid option. “When ‘dumb’ money acknowledges its limitations,” says Buffett, “it ceases to be dumb.”3

Diversification may seem like a simple and obvious strategy. But it is no more than a method to achieve certain goals. So those goals must first be defined. Only then can you build a system that will meet them.

The Wall Street wisdom is to put X percent of your portfolio into bonds, Y percent into stocks, and Z percent into cash—with stock market investments further diversified into a variety of categories from so-called conservative “widow and orphan” stocks to high-risk “flavor of the month”–type stocks.

But the aim of this strategy isn’t to preserve capital (which it may) but to reduce the risk of loss. These are two quite different objectives.

I’ve only seen one well-thought-out investment strategy that successfully applies diversification to the aim of not just preserving capital, but increasing that capital’s real purchasing power over time. It was developed by Harry Browne, who named it the Permanent Portfolio. Its purpose, he says, “is to assure that you’re financially safe no matter what the future brings.”4

Browne started from the premise that it’s impossible to predict the future price of any investment. But it is possible to foresee the impact of different economic conditions on different classes of assets. For example, when inflation is high the price of gold usually rises, while the higher interest rates that usually accompany rising inflation push down the prices of long-term bonds. During a recession, however, interest rates usually fall, so bonds rise, sometimes skyrocketing, while gold and stocks tend to fall in value.

Browne identified four different classes of investments, each “a cornerstone of a Permanent Portfolio because each has a clear and reliable link to a specific economic environment.”5

Stocks, which profit in times of prosperity;

Gold, which profits when inflation is rising;

Bonds, which rise in value when interest rates fall; and,

Cash, which provides stability to the portfolio and gains in purchasing power during deflation.

With 25 percent of the portfolio in each category, at almost any time the value of one of those categories will be rising. There will, of course, be occasional periods when everything is stagnant. But those times are rare.

The key to making the Permanent Portfolio work is volatility. By choosing the most volatile investments in each category, the profit on just one quarter of the portfolio’s assets can more than compensate for any declines in the other categories. So Browne recommends investing in highly volatile stocks, mutual funds that invest in such stocks, or long-term warrants for the stock market portion of the portfolio. By the same reasoning, he advises holding thirty-year bonds or even zero-coupons for the bond portion, as they are far more sensitive to interest rate changes than bonds that mature in just a few years time.

The portfolio can also be diversified geographically to protect against political risk by holding a portion of the gold or cash holdings offshore—in, say, a Swiss bank.

The portfolio only needs to be rebalanced once a year to bring each category back to 25 percent of the portfolio. For the rest of the year you can literally forget about your money.

The “turnover” of the portfolio is minimal, rarely more than 10 percent a year. So both transaction costs and taxes are kept very low. And in the years that you are earning income, the chances are that you’ll be adding to your portfolio every year. With the Permanent Portfolio approach, that would usually mean buying more of the investments that have fallen in price. So most years you’d only be liable for taxes on interest and dividend income from your bonds, T-bills, and stocks. You would rarely pay any capital gains taxes on your investments until you retire.

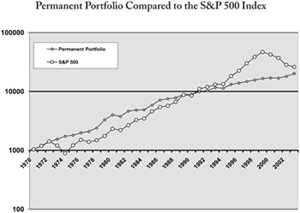

The return on this approach is a quite remarkable 9.24 percent per annum (from 1970 to 2002), compared to 10.07 percent per annum for the S&P 500 index. And, as this chart shows, the Permanent Portfolio appears to rise inexorably in value while stocks provide many sleepless nights.

Harry Browne’s Permanent Portfolio is a well-thought-out investment system that applies intelligent diversification to the objective of preserving capital and, indeed, increasing that capital’s purchasing power over time.

Its returns pale by comparison to those achieved by Buffett and Soros. The difference is the amount of time and energy that you must devote to your investments: as little as a few hours per year to successfully manage a Permanent Portfolio, compared to the intensity of time and effort that most other investment systems require.

If you have decided that there are other things you’d rather do in life than worry about your money, intelligent diversification is an option worth considering. You might like to adopt Browne’s Permanent Portfolio approach, or you might prefer to create your own method of intelligent diversification. The important thing is, like Browne’s Permanent Portfolio, the method you use should still meet all the Master Investor’s standards for a complete investment system.